Urmilla Deshpande's Blog, page 3

September 17, 2012

9/13/2012 ~ Marathi translation of A Pack of Lies

My Marathi is good enough to talk to my sister (whose Marathi is worse than mine), and not at all good enough to read the translation.

My Marathi is good enough to talk to my sister (whose Marathi is worse than mine), and not at all good enough to read the translation.

This translation happened with my technical and legal consent. There was a clause in the contract with my publisher which allowed them to sell the translation rights. Needless to say, I learned my lesson. Neither the translator, to my shock and disappointment, nor the publisher, made ANY contact with me during the translation process. Two copies of this Marathi version arrived in my mailbox, and that was how I found out.

To start with, the title of the book translates back to English approximately as “I Will Lie” which immediately said to me that the title was chosen for market impact . It does not say what I intended. I was not, to put it mildly, delighted. I opened the book, and with some apprehension, read the acknowledgements. And at that point I figured that I would probably drop an eyeball if I read any more. There was a clear mistake in understanding what I meant by “my sisters”, and the translator has taken the liberty of assuming my meaning without bothering to check. At that point I gave up. It seems to me, from what I could tell from reviews of the book, that basically this is now a terrible book. The publisher’s blurb on the cover also sensationalizes it for no reason, as “explosive” and so forth. Sleaze.

My mother, Gauri Deshpande, worked on several translations. She talked to the authors, or, in the case of Sir Richard, did an enormous amount of research and put a lot of thought into it, sometimes agonizing over single words. Shashi Deshpande, who translated my mother’s “Deliverance”, too, did the same. I can’t understand why a translator would not even have a phone conversation with an author whose book she is translating – I am neither dead nor unapproachable.

Anyone who has actually read it in both languages, if there is such a person, I would love to hear what you have to say. Maybe it is not as terrible as I fear. But from what little I have read, I fear it is.

September 16, 2012

9/13/2012 ~ Marathi translation of A Pack of Lies

My Marathi is good enough to talk to my sister (whose Marathi is worse than mine), and not at all good enough to read the translation.

My Marathi is good enough to talk to my sister (whose Marathi is worse than mine), and not at all good enough to read the translation.

This translation happened with my technical and legal consent. There was a clause in the contract with my publisher which allowed them to sell the translation rights. Needless to say, I learned my lesson. Neither the translator, to my shock and disappointment, nor the publisher, made ANY contact with me during the translation process. Two copies of this Marathi version arrived in my mailbox, and that was how I found out.

To start with, the title of the book translates back to English approximately as “I Will Lie” which immediately said to me that the title was chosen for market impact . It does not say what I intended. I was not, to put it mildly, delighted. I opened the book, and with some apprehension, read the acknowledgements. And at that point I figured that I would probably drop an eyeball if I read any more. There was a clear mistake in understanding what I meant by “my sisters”, and the translator has taken the liberty of assuming my meaning without bothering to check. At that point I gave up. It seems to me, from what I could tell from reviews of the book, that basically this is now a terrible book. The publisher’s blurb on the cover also sensationalizes it for no reason, as “explosive” and so forth. Sleaze.

My mother, Gauri Deshpande, worked on several translations. She talked to the authors, or, in the case of Sir Richard, did an enormous amount of research and put a lot of thought into it, sometimes agonizing over single words. Shashi Deshpande, who translated my mother’s “Deliverance”, too, did the same. I can’t understand why a translator would not even have a phone conversation with an author whose book she is translating – I am neither dead nor unapproachable.

Anyone who has actually read it in both languages, if there is such a person, I would love to hear what you have to say. Maybe it is not as terrible as I fear. But from what little I have read, I fear it is.

February 18, 2012

2/18/2012 ~ Blog Review of Gauri Deshpande’s “Deliverance”

Deepa Deosthalee, in her blog Book Impressions, reviews Deliverance, and comments on A Pack of Lies.

http://www.filmimpressions.com/books/2012/02/deliverance-.html

An excerpt from the review:

“… Whether it was motherhood, womanhood, marriage, relationships or life itself, Gauri Deshpande had the ability to be brutally honest, much to the chagrin of the male establishment of the time. In this, her most autobiographical story, she examines her difficult relationship with her daughters, not sparing herself or them and in the process, filtering her own experiences into evocative literature — the hallmark of many a great woman writer.

Interestingly, her daughter Urmilla Deshpande followed in her footsteps by exploring the same relationship from her point-of-view in her novel A Pack of Lies a couple of years ago. Gauri would have been proud even though her daughter’s portrait of her was far from flattering. In fact, reading both these stories as companion pieces makes for an interesting study of how differently two people can look at the same situation from different vantage points…”

2/18/2012 ~ Blog Review of Gauri Deshpande's "Deliverance"

Deepa Deosthalee, in her blog Book Impressions, reviews Deliverance, and comments on A Pack of Lies.

http://www.filmimpressions.com/books/2012/02/deliverance-.html

An excerpt from the review:

"… Whether it was motherhood, womanhood, marriage, relationships or life itself, Gauri Deshpande had the ability to be brutally honest, much to the chagrin of the male establishment of the time. In this, her most autobiographical story, she examines her difficult relationship with her daughters, not sparing herself or them and in the process, filtering her own experiences into evocative literature — the hallmark of many a great woman writer.

Interestingly, her daughter Urmilla Deshpande followed in her footsteps by exploring the same relationship from her point-of-view in her novel A Pack of Lies a couple of years ago. Gauri would have been proud even though her daughter's portrait of her was far from flattering. In fact, reading both these stories as companion pieces makes for an interesting study of how differently two people can look at the same situation from different vantage points…"

September 1, 2011

09/01/2011 ~ “Spanking Words” ~ Roselyn D’Mello

http://www.himalmag.com/component/content/article/4633-spanking-words.html

… Steer clear

of the opaque. Quirkiness is useful,

so is translucence. Spank

words carefully. Include

lots of skin, mouth,

tongue. However aesthetic

breasts work the best. Linger.

In her poem ‘How to Write Erotica’, Nitoo Das comes exactingly close to articulating what it is about the genre that makes it so coveted and yet so controversial, and most of all so elusive. Contrary to popular belief, a thick barrier lined with barbed wire separates erotica from pornography. If ‘pornography is the attempt to insult sex,’ as D H Lawrence suggested in his essay ‘On Pornography’, erotica is the attempt to celebrate its roots – desire. The two genres are motivated by entirely different impulses, but it is the degree to which the act of sex is alluded that demarcates the boundaries.

If there is still any confusion, the simplest rule of thumb is the level of facility it takes to dabble in either genre. Place a camera mechanically in front of a masturbating woman and you have pornography. Instead, document the sensation, the rush of blood from clitoris to head as she writhes and combusts and swims in wave after ecstatic wave until her lips contort into an open mouth, until the quivering ceases after the final gasp, the penultimate sigh. Erotica is what you will have produced. Pornography is a cakewalk. It does not necessitate the use of one’s imagination. But to write a single line of erotica from scratch, you must first create the universe.

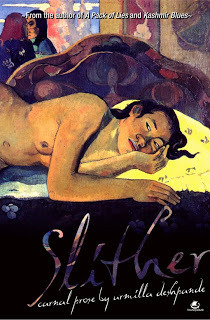

That is precisely what Urmilla Deshpande seems to have done in Slither, her collection of erotic stories published by Tranquebar. The cover defines this body of work as ‘carnal prose’, and with every story a new dimension of this secret universe of flesh and fire unravels. The atmosphere is dense with alternating layers of desire and desperation: a single fertile river that runs underground and bifurcates into diverse streams of consciousness, infusing and irrigating everything it encompasses with passion and intrigue. The landscape is peopled with characters who live ordinary lives and who dabble routinely with the mundane, but who experience the world in all its sensual glory. But Deshpande’s true genius lies in her ability to play with the texture of language, to ‘spank words carefully’ and to create a dialogue between touch and the sensation of that touch – and, often, the longing for it. And finally, her capacity to linger in the afterglow of language so that what arouses the reader is not merely the quirkiness of the situation at hand but the symphony that her words conduct.

For instance, the title story is not so much about sex; the focus is on the impassioned lack of it. A woman of indefinite age tells us about her botanist husband, who is more aroused by Amazon gingers than her. She rants:

And still I loved his hands. I wonder what it is about him that rejects me over and over. It is not that he does not look at me. But it is not with the eyes of a lover that he sees me. It is with the eyes of a botanist. He sees my eyes – humans have two, plants none, so perhaps they do not impress him, though they are, I am told, fine eyes. He touches my skin, but with his fingertips, not his whole hands, through my clothes, not with the delight of knowing I’m right there below that layer but with some practical purpose – to guide me through some forest path perhaps, or stop me as he did that day to watch those snakes. He even lays with me, often enough that I would not notice this disinterest, but not often enough that I felt elevated above Amazon gingers.

The 18 stories spread over nearly 300 pages embody a range of characters who are, more often than not, of Indian descent, though not always located in India. Among the most notable we have the botanist’s wife, who finds herself seduced by a village chief in a village along the foothills of the Himalaya; an emotionally unavailable taxidermist who finds herself attracted to another emotionally unavailable person; a member of a family of spirits who can enter and control people’s bodies, a village girl who grows up to be an internationally acclaimed swimmer and who is desperate to lose her virginity and finally does so – at 50.

‘Goblin Market,’ Deshpande’s retelling of the eponymous poem by Christina Rosetti, is easily the most subversive. Here, the two sisters Lizzie and Laura are lovers, and the goblins in question are ravaging beasts with the power to corrupt one’s innocence.

Laura could not resist the smell of the fruit, and the goblins licking them off her, off her breasts, biting and sucking and grabbing her, and then off her cunt, they gathered around it like creatures at a watering hole, lapping, sucking, squealing and pushing each other, fighting for the juices that flowed from her.

‘Isis’ and ‘Slight Return’ are the two other strongest stories. In ‘Isis’, the narrator, a young writer, gets increasingly obsessed with the title character, a yesteryears actress whom he would keep hearing about through his grandfather, who always speaks of her lustfully. He decides to write a book based on her and finally meets this almost mythical figure, finding himself further intrigued by her grace, her beauty and her missing eye. ‘Slight Return’ is a heartbreakingly beautiful story about Suman, a middle-aged woman and victim of a bad marriage, who finds herself transfixed as she chances upon her daughter clandestinely making love to her boyfriend in the dark. Her reaction is not one of horror or shame; instead, given her own negative sexual history and her experience with rape victims and prostitutes, she finds herself strangely appreciative of her daughter’s sexuality and her ability to articulate it. The act of looking is not voyeuristic; rather, it is tempered by tenderness and wisdom.

Each story in the collection has a personality of its own. Despite the phenomenal range and variety of the plots, you find yourself relating to and remembering the context of each narrative. Moreover, there is a dexterous quality to the language, a stylistic flexibility. Deshpande juggles different techniques of narration, from first-person to third, and each voice is unique so there is no room for repetition or monotony. This is a commendable feat considering what are, in this reviewer’s opinion, the limitations of the vocabulary of the English language, particularly when it comes to describing either sex

or intimacy.

Holy well

While the Subcontinent has a rich history of erotica, most of the pre-modern erotic writing by women has been within the domain of the devotional, by Bhakti women poets like Meera and Akka Mahadevi, the 12th-century saint from Karnataka. Given this history, erotica by contemporary Indian women writers could be read in the same vein as casual sex, an indulgence, writing for pleasure, which is precisely why the Indian moral brigade got its panties in a twist when writers such as Kamala Das started to write the way she did, irreverently and indulgently focusing on her erotic self. Erotica continues to be a controversial genre, which explains most women’s preference for adopting pseudonyms. While it is acceptable for men to brag about their sexual exploits, it is still taboo for women writers. The few women who do, usually hesitate to sign their real names to their writing.

Writers who so much as hint at being sexually experienced – such as Meena Kandasamy, who openly writes about the experience of being Dalit and a woman, and Mridula Garg – often have to bear the brunt of moral hypocrisy. Writing erotica comes at the price of one’s reputation. Ruchir Joshi’s introduction to Electric Feather is testimony. Joshi explains the difficulty he experienced in soliciting stories. ‘One senior Indian writer, who writes brilliant erotics, disdained to even answer my email. Three others did variations of sputtering into their beer, “Me write porn for you!?! No fucking way!” and promptly crossed their legs, all three. One star of the firmament smiled very sweetly and said, “If I find the time, I’ll certainly think about it.”’

Deshpande is possibly the first contemporary Indian author in English to publish a collection of stories devoted entirely to the erotic. In the last two years, though, a host of writers, particularly women, have been appropriating the space of the erotic. Most significant among them is the young provocative and award-winning M Svairini, who writes the rather risqué blog, ‘The Bottom Runs the Fuck’, and who recently published a piece in The First Post in defence of a ‘Masturbat-a-thon’. In a monologue titled ‘Kaliyuga Yoni’, which was originally written to be performed as part of ‘Yoni Ki Baat’, an ensemble show conceived along the lines of Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues, Svairini’s narrator personifies her vagina and simultaneously takes a stand on the much-debated issue about the use of the word cunt or even vagina in erotica.

She [my vagina] doesn’t like the word yoni; in English, it sounds spiritual and soft, new agey, shallow as a henna tattoo.

She prefers cunt, as in wet cunt, nasty cunt, naughty cunt, bad cunt, good cunt, beautiful cunt. Cunt from the Sanskrit word for well, or spring, a deep source: kund, as in kundalini. As in the word for menstrual blood: kundapushpa, flower of the holy well. Red Violent. The taste of birth and death, of origins.

Svairini is also a prominent member of an interesting online collective of Southasian writers that calls itself ‘Shameless Yonis’. Other members include Kama Spice, writer of an erotic trilogy, Kessa’s Pride and Sehra’s Honour and Tia’s War, based in a world where people shape-shift between being human and feline. Aisha Nayar, Sabah Guille and Sheherzade are the other permanent members of the collective. Every month, the blog (www.shamelessyonis.wordpress.com) features a guest writer who similarly pushes the genre to new and exciting heights.

As more and more publishers are waking up to the marketing potential of the erotica genre, more and more women are waking up to its capacity for subversion – this is especially so given the recent success of the Slut Walk phenomenon, with urban women becoming increasingly comfortable expressing their right to pleasure. Not only does it arouse and titillate, erotica also seems to offer women space to either articulate or satisfy desire, while answering 20th-century French feminist Helene Cixous’s revolutionary call to women to ‘write their bodies’.

~ Roselyn D’Mello is a journalist and writer in Delhi.

09/01/2011 ~ "Spanking Words" ~ Roselyn D'Mello

http://www.himalmag.com/component/content/article/4633-spanking-words.html

… Steer clear

of the opaque. Quirkiness is useful,

so is translucence. Spank

words carefully. Include

lots of skin, mouth,

tongue. However aesthetic

breasts work the best. Linger.

In her poem 'How to Write Erotica', Nitoo Das comes exactingly close to articulating what it is about the genre that makes it so coveted and yet so controversial, and most of all so elusive. Contrary to popular belief, a thick barrier lined with barbed wire separates erotica from pornography. If 'pornography is the attempt to insult sex,' as D H Lawrence suggested in his essay 'On Pornography', erotica is the attempt to celebrate its roots – desire. The two genres are motivated by entirely different impulses, but it is the degree to which the act of sex is alluded that demarcates the boundaries.

If there is still any confusion, the simplest rule of thumb is the level of facility it takes to dabble in either genre. Place a camera mechanically in front of a masturbating woman and you have pornography. Instead, document the sensation, the rush of blood from clitoris to head as she writhes and combusts and swims in wave after ecstatic wave until her lips contort into an open mouth, until the quivering ceases after the final gasp, the penultimate sigh. Erotica is what you will have produced. Pornography is a cakewalk. It does not necessitate the use of one's imagination. But to write a single line of erotica from scratch, you must first create the universe.

That is precisely what Urmilla Deshpande seems to have done in Slither, her collection of erotic stories published by Tranquebar. The cover defines this body of work as 'carnal prose', and with every story a new dimension of this secret universe of flesh and fire unravels. The atmosphere is dense with alternating layers of desire and desperation: a single fertile river that runs underground and bifurcates into diverse streams of consciousness, infusing and irrigating everything it encompasses with passion and intrigue. The landscape is peopled with characters who live ordinary lives and who dabble routinely with the mundane, but who experience the world in all its sensual glory. But Deshpande's true genius lies in her ability to play with the texture of language, to 'spank words carefully' and to create a dialogue between touch and the sensation of that touch – and, often, the longing for it. And finally, her capacity to linger in the afterglow of language so that what arouses the reader is not merely the quirkiness of the situation at hand but the symphony that her words conduct.

For instance, the title story is not so much about sex; the focus is on the impassioned lack of it. A woman of indefinite age tells us about her botanist husband, who is more aroused by Amazon gingers than her. She rants:

And still I loved his hands. I wonder what it is about him that rejects me over and over. It is not that he does not look at me. But it is not with the eyes of a lover that he sees me. It is with the eyes of a botanist. He sees my eyes – humans have two, plants none, so perhaps they do not impress him, though they are, I am told, fine eyes. He touches my skin, but with his fingertips, not his whole hands, through my clothes, not with the delight of knowing I'm right there below that layer but with some practical purpose – to guide me through some forest path perhaps, or stop me as he did that day to watch those snakes. He even lays with me, often enough that I would not notice this disinterest, but not often enough that I felt elevated above Amazon gingers.

The 18 stories spread over nearly 300 pages embody a range of characters who are, more often than not, of Indian descent, though not always located in India. Among the most notable we have the botanist's wife, who finds herself seduced by a village chief in a village along the foothills of the Himalaya; an emotionally unavailable taxidermist who finds herself attracted to another emotionally unavailable person; a member of a family of spirits who can enter and control people's bodies, a village girl who grows up to be an internationally acclaimed swimmer and who is desperate to lose her virginity and finally does so – at 50.

'Goblin Market,' Deshpande's retelling of the eponymous poem by Christina Rosetti, is easily the most subversive. Here, the two sisters Lizzie and Laura are lovers, and the goblins in question are ravaging beasts with the power to corrupt one's innocence.

Laura could not resist the smell of the fruit, and the goblins licking them off her, off her breasts, biting and sucking and grabbing her, and then off her cunt, they gathered around it like creatures at a watering hole, lapping, sucking, squealing and pushing each other, fighting for the juices that flowed from her.

'Isis' and 'Slight Return' are the two other strongest stories. In 'Isis', the narrator, a young writer, gets increasingly obsessed with the title character, a yesteryears actress whom he would keep hearing about through his grandfather, who always speaks of her lustfully. He decides to write a book based on her and finally meets this almost mythical figure, finding himself further intrigued by her grace, her beauty and her missing eye. 'Slight Return' is a heartbreakingly beautiful story about Suman, a middle-aged woman and victim of a bad marriage, who finds herself transfixed as she chances upon her daughter clandestinely making love to her boyfriend in the dark. Her reaction is not one of horror or shame; instead, given her own negative sexual history and her experience with rape victims and prostitutes, she finds herself strangely appreciative of her daughter's sexuality and her ability to articulate it. The act of looking is not voyeuristic; rather, it is tempered by tenderness and wisdom.

Each story in the collection has a personality of its own. Despite the phenomenal range and variety of the plots, you find yourself relating to and remembering the context of each narrative. Moreover, there is a dexterous quality to the language, a stylistic flexibility. Deshpande juggles different techniques of narration, from first-person to third, and each voice is unique so there is no room for repetition or monotony. This is a commendable feat considering what are, in this reviewer's opinion, the limitations of the vocabulary of the English language, particularly when it comes to describing either sex

or intimacy.

Holy well

While the Subcontinent has a rich history of erotica, most of the pre-modern erotic writing by women has been within the domain of the devotional, by Bhakti women poets like Meera and Akka Mahadevi, the 12th-century saint from Karnataka. Given this history, erotica by contemporary Indian women writers could be read in the same vein as casual sex, an indulgence, writing for pleasure, which is precisely why the Indian moral brigade got its panties in a twist when writers such as Kamala Das started to write the way she did, irreverently and indulgently focusing on her erotic self. Erotica continues to be a controversial genre, which explains most women's preference for adopting pseudonyms. While it is acceptable for men to brag about their sexual exploits, it is still taboo for women writers. The few women who do, usually hesitate to sign their real names to their writing.

Writers who so much as hint at being sexually experienced – such as Meena Kandasamy, who openly writes about the experience of being Dalit and a woman, and Mridula Garg – often have to bear the brunt of moral hypocrisy. Writing erotica comes at the price of one's reputation. Ruchir Joshi's introduction to Electric Feather is testimony. Joshi explains the difficulty he experienced in soliciting stories. 'One senior Indian writer, who writes brilliant erotics, disdained to even answer my email. Three others did variations of sputtering into their beer, "Me write porn for you!?! No fucking way!" and promptly crossed their legs, all three. One star of the firmament smiled very sweetly and said, "If I find the time, I'll certainly think about it."'

Deshpande is possibly the first contemporary Indian author in English to publish a collection of stories devoted entirely to the erotic. In the last two years, though, a host of writers, particularly women, have been appropriating the space of the erotic. Most significant among them is the young provocative and award-winning M Svairini, who writes the rather risqué blog, 'The Bottom Runs the Fuck', and who recently published a piece in The First Post in defence of a 'Masturbat-a-thon'. In a monologue titled 'Kaliyuga Yoni', which was originally written to be performed as part of 'Yoni Ki Baat', an ensemble show conceived along the lines of Eve Ensler's The Vagina Monologues, Svairini's narrator personifies her vagina and simultaneously takes a stand on the much-debated issue about the use of the word cunt or even vagina in erotica.

She [my vagina] doesn't like the word yoni; in English, it sounds spiritual and soft, new agey, shallow as a henna tattoo.

She prefers cunt, as in wet cunt, nasty cunt, naughty cunt, bad cunt, good cunt, beautiful cunt. Cunt from the Sanskrit word for well, or spring, a deep source: kund, as in kundalini. As in the word for menstrual blood: kundapushpa, flower of the holy well. Red Violent. The taste of birth and death, of origins.

Svairini is also a prominent member of an interesting online collective of Southasian writers that calls itself 'Shameless Yonis'. Other members include Kama Spice, writer of an erotic trilogy, Kessa's Pride and Sehra's Honour and Tia's War, based in a world where people shape-shift between being human and feline. Aisha Nayar, Sabah Guille and Sheherzade are the other permanent members of the collective. Every month, the blog (www.shamelessyonis.wordpress.com) features a guest writer who similarly pushes the genre to new and exciting heights.

As more and more publishers are waking up to the marketing potential of the erotica genre, more and more women are waking up to its capacity for subversion – this is especially so given the recent success of the Slut Walk phenomenon, with urban women becoming increasingly comfortable expressing their right to pleasure. Not only does it arouse and titillate, erotica also seems to offer women space to either articulate or satisfy desire, while answering 20th-century French feminist Helene Cixous's revolutionary call to women to 'write their bodies'.

~ Roselyn D'Mello is a journalist and writer in Delhi.

August 22, 2011

08.22.2011 ~ Slither review

http://thebookloversreview.blogspot.com/2011/08/review-slither.html

This is going to be a really short post but wanted to review this book simply because it is a 'hatke' book on a topic which we Indians talk about only in a hush hush, conspiratorial way. This is a book of short stories that are erotic in nature with the undercurrent of carnality.

The author in her acknowledgement says that this book was the result of a challenge from her editor friend and goes on to candidly admits that the book was uncomfortable to write but at the same time also empowering and liberating.

Fair enough. So I started to read but some stories down I could figure why writing stories like this is a tough ask. Stories were great but after a point I struggled to finish the book, not because of the writing let me be clear, but the subject. There is only so much one can read about slithering bodies, sex et al..you get the drift?

Maybe I am in minority where my reasons are concerned, but kudos to the author for taking up this challenge and doing full justice to it.

So if this genre interests you do pick up the book!

August 18, 2011

8.18.2011 ~ Slither Reviewed

Book Review: Slither

15/08/2011

BY URVASHI BAHUGUNA

Stories, incredibly human, wrap themselves around these vignettes of lust. Sometimes, there is profound unhappiness in the places where lust has earlier been; people and times encoded into spaces and movements. Sometimes, there is staleness, a burnt taste even, and there is the realisation that there is as much wariness in people as there in anticipation.

Urmilla Deshpande's Slither shows how memory works in mysterious ways, and how corporeal events sometimes cling longer than emotional ones. Wet plunges into the India that is statistically prominent and where sex is still taboo and marriage sacred to the point of being above all questioning. Xen is about inexperience and fumbling, and the choices that arise simply because there have never been any before.

A handful of these stories map the differing circuitous routes marriage takes to reconcile love and sex, to manoeuvre pursuing one without the other and to live with the aftermath of waning of either or both. The book throws up questions, not so inexpertly so as to appear forced and not so impartial as to be unperceivable. Arranged marriage has complex sexual associations, and some of them unpleasant. Revulsion and fear lurk where in different circumstances something else could have been. Other types of marriages unknot too in his anthology, giving way to time and irritance.

The artist with his naked muses in Cosmic Latte will ruffle a few feathers, but most people will not be able to look beyond the nudes to him.

"But my paintings were not so bad. There were actual women attached to the body parts, and they were women I loved, and painted with love, and I think that came through."

The accidental, superficial lust one feels for virtual strangers and celebrities plays out in D.U.I. and Isis. Both play out theatrically, similar to dream sequences just as fantasies would. Sex, real and imagined, desired and forced, implied and overt, attempted and unfulfilled; a strange spectrum is travelled by reading this book.

Sometimes, the thumbnails she draws from are clichés, the people you encounter in movies, not run into on the sidewalk. Deshpande puts her own spin on every story, but she tumbles back into the realm of the expected with a faulty line or two that betrays a lack of originality. It takes a lot to revamp a cliché, and some of the stories fall short of doing just that. Society's misfits have had too much screen time to appeal easily to the more avid reader.

The book is worth reading. It strays into strange waters, places that urban India still takes the long way around. A few pieces here and there disappoint, but when you finish the book, you know she took you a step in the right direction. Because it's easy to forget that as Deshpande says in Taxidermy: "There are things we need, looks, touches, moments, that have nothing immediate to do with survival."

[Tranquebar; ISBN 9789380658841]

August 8, 2011

08.08.2011 ~ Tranquebar blog

August 1, 2011

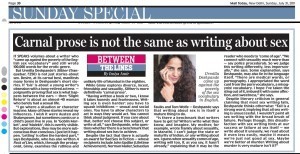

8.01.2011 ~ Mail Today, New Delhi, Sunday

Mail Today, New Delhi, Sunday, July 31, 2011: Between the Lines by Insiya Amir

Mail Today, New Delhi, Sunday, July 31, 2011: Between the Lines by Insiya Amir

Carnal prose is not the same as writing about sex

IT SPEAKS volumes about a writer who "came up against the poverty of the English sex vocabulary" and still wrote 100,000 words for the erotic genre. But Urmilla Deshpande's Slither (Tranquebar, Rs.250) is not just stories about sex. Desire, at its carnal best, manifests many forms in Deshpande's short stories. If 'Isis' is about a young writer's obsession with a long-retired actress — poignantly proving that sex is what happens between the ears — then 'Slight Return' is about an almost-40 woman who barely had a sexual life. "I go where a situation or character lead me. Many of these stories reveal my influences. I wish it were Austen and Shakespeare, but sometimes comics or a child's poem live in you. In 'Goblin Market', and 'Malekh', this is overtly visible. But explorations, they may be more subconscious than conscious. I just let it happen. 'Letting' is often the hardest part," says Deshpande, who has also written A Pack of Lies, which, through the protagonist, Ginny, examines the ruthless and unlikely life of Mumbai in the eighties. While Ginny explores divorce, incest, friendship and sexuality, Slither is more definitively 'carnal prose'. "Having written a book or two, I know it takes honesty and fearlessness. Writing sex is even harder: you have to squash inhibitions — sexual and social ones. You have to allow characters to act in ways they would act. You cannot think about judgment. If you care about that, better not choose this subject, or write at all," says Deshpande, who questions whether there is a benchmark that writing about sex has to achieve.

Despite the fact that there is actually an award for Bad Sex in Fiction — whose recipients include John Updike (Lifetime Achievement), Norman Mailer, Sebastian Faulks and Tom Wolfe — Deshpande says that writing about sex is in itself a mature thing to do. "Is there a benchmark that writers have to get to? Writers write what they know, and imagine. My mother, for example, wrote frankly about sexuality, in Marathi. I can't judge the state or maturity of Indian, or any writing about sex. I guess when sexuality comes of age, writing will too, if, as you say, it hasn't already," explaining that it may be the reader who needs to 'come of age'. "We connect with sexuality much more than— say police procedurals. So we judge this writing differently, less impersonally," she says. Some explanation, says Deshpande, may also lie in the language itself. "There are medical words, or pornography. I appropriated the word cunt from the porn vocabulary, a misogynist vocabulary. I hope I've taken the sting out of it, imbued it with some affection, and sweetness," she says.

Despite literary criticism in general claiming that most sex writing fails, Deshpande thinks otherwise: "Fail is a strong word, implying that all sex writing is unsuccessful. I wouldn't paint all sex writing with the broad brush of failure. Perhaps though, this dissatisfaction with sex writing hints at our success or failure at sex itself — we write about it uneasily, we read about it even less easily, maybe it means we're just not good at sex. Maybe we're better at murder. Writing about murder is very mature isn't it?"

Urmilla Deshpande's Blog

- Urmilla Deshpande's profile

- 12 followers