Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 145

June 30, 2011

The Darker Side of 19th Century London - Chunee

Back in March, there was a news story about Anne (above), the 59 year old Asian elephant whose abuse at the hands of her Romanian groom was caught on tape. You can read the full story here and, if you have the stomach for it, you can read the heartbreaking story written by the journalist who met her here. The abuse videos are embedded in the story, but I chose not to watch them. Anne has been with the Bobby Roberts Super Circus in England since she was a baby and video tape exposed her abuse while the circus was in Northamptonshire during a break in performances, although reports are that this is not the first incident. She could not escape her attacker because she was chained to the floor. The story brought to mind the very sad tale of another elephant, Chunee, who met a tragic end in Regency London and I wondered at the fact that, nearly 200 years on, nothing much had changed in the way that these poor animals are handled.

Chunee was an Indian elephant first brought to London and exhibited at the Covent Garden Theatre circa 1810, and later bought and exhibited at the menagerie at the Exeter Exchange in the Strand. James Hogg and Florence Marryat describe the Exchange in London Society, Volume 6 (1864) -

"After being used for various public uses, the upper story was occupied as a menagerie, successively by Pidcock, Polito, and Cross: fifty years ago, the sight-lover had to pay half a crown to see a few animals confined in small dens and cages in rooms of various sizes, the walls painted with exotic scenery to favour the illusion; whereas now, the finest collection of living animals in Europe may be seen in a beautiful garden for sixpence! The roar of the Exchange lions and tigers could distinctly be heard in the street, and often frightened horses in tho roadway.

"Chunee had achieved theatrical distinction: he had performed in the spectacle of `Blue Beard,' at Covent Garden; and he kept up an acquaintance with Edmund Kean, whom he would fondle with his trunk, in return for a few loaves of bread. The greatness of the Exeter Change menagerie departed with Chunee; the animals were removed, in 1828, to the King's Mews; and Exeter Change was entirely taken down in 1830."

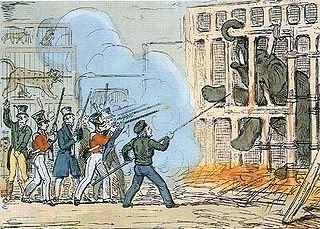

As Wikipedia tells us, in 1826 "Chunee became dangerously violent towards the end of his life, attributed to an "annual paroxysm" (perhaps his musth) aggravated by a rotten tusk which gave him a bad toothache. On 26 February 1826, while on his usual Sunday walk along the Strand, Chunee ran amok, killing one of his keepers. He became increasingly enraged and difficult to handle over the following days, and it was decided that he was too dangerous to keep. The following Wednesday, 1 March, his keeper tried to feed him poison, but Chunee refused to eat it. Soldiers were summoned from Somerset House to shoot Chunee with their muskets. Kneeling down to the command of his trusted keeper, Chunee was hit by 152 musket balls, but refused to die. Chunee was finished off by a keeper with a harpoon or sword. The floor of his cage was deeply covered with his blood, and it was said that the sound of the elephant in agony was more alarming than the reports of the soldier's guns."

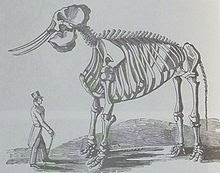

And London Society adds, "During Cross' tenancy, in 1826, Chunee, the stupendous elephant which had been shown here since 1809, having become ungovernable, was put to death by firing ball to the number of 152! Chunee weighed nearly five tons, and stood eleven feet in height. Cross valued the animal at 1000 pounds; and its den, of solid oak and hammered iron, cost 350/. The dissection of Chunee was a mighty labour: the body was raised by a pulley to a cross-beam, and first flayed, which it took twelve active men near twelve hours to accomplish. Next day (Sunday), the dissection was commenced, Mr. Brookes, Mr. Caesar Hawkins, Mr. Herbert Mayo, Mr. Bell, and other eminent surgeons being present; and there, too, was Mr. Yarrell, the naturalist, to watch the strange operations. The carcase being raised, the trunk was first cut off; then the eyes were extracted; then the contents of the abdomen, pelvis, and chest were removed. When the body was opened, the heart—nearly two feet long, and eighteen inches broad—was found immersed in five or six gallons of blood; the flesh was then cut from the bones, and was removed from the menagerie in carts. Two large steaks were cut off and broiled, and declared, by those who had the courage to partake of them, to be a fine relish. Spurzheim, the phrenologist, who was present, was anxious to dissect Chunee's brain, but Mr. Cross objected, as the crown of the head must then have been sawn off. The skin, which weighed 17 cwt., was sold to a tanner for 50/.; the bones weighed 876 lbs.; and the entire skeleton, sold for 100/., is now in the museum of the College of Surgeons, in Lincoln's Inn Fields."

Chunee's skeleton was destroyed during a bombing raid in 1941.

Sked 6/30

Glad to say that Anne is now . . . .

Published on June 30, 2011 00:34

June 29, 2011

Mrs. Sage, The First Englishwoman Aeronaut

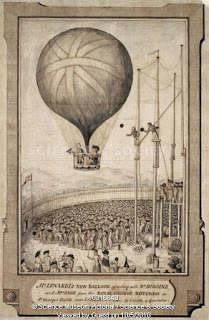

Mrs Laetitia Sage became the first English woman to fly in a hydrogen balloon in Vincent Lunardi's ascent of 29 June 1785. Vincent (or Vincenzo) Lunardi (1759-1806), was Italian secretary to the Neapolitan ambassador in London and had made the first ascent in a hydrogen balloon in Britain on 15 September 1784 from Moorfields in London. Unfortunately, the combined weight of Mrs Sage and the other two passengers, George Biggin and Colonel Hastings, was too much for the balloon. Lunardi and Hastings agreed to stay behind, allowing Mrs Sage and Biggin, a wealthy Etonian, to continue alone. Together they flew in a red, white and blue balloon from St. George's Fields in London, over St James's Park and Piccadilly, before landing over two hours later in fields near Harrow.

Mrs Laetitia Sage became the first English woman to fly in a hydrogen balloon in Vincent Lunardi's ascent of 29 June 1785. Vincent (or Vincenzo) Lunardi (1759-1806), was Italian secretary to the Neapolitan ambassador in London and had made the first ascent in a hydrogen balloon in Britain on 15 September 1784 from Moorfields in London. Unfortunately, the combined weight of Mrs Sage and the other two passengers, George Biggin and Colonel Hastings, was too much for the balloon. Lunardi and Hastings agreed to stay behind, allowing Mrs Sage and Biggin, a wealthy Etonian, to continue alone. Together they flew in a red, white and blue balloon from St. George's Fields in London, over St James's Park and Piccadilly, before landing over two hours later in fields near Harrow.Mrs Sage was described as Junoesque, and apparently weighed in at over 200 pounds. In a later account, Mrs. Sage blamed herself for the balloon going over the weight limit, as she hadn't volunteered her exact weight to Mr. Lunardi and he'd been too polite to ask it of her. The gondola was draped in swags, but the gate had a neat arrangement of lacing so that the watchers on the ground could see the people up in the air. Upon exiting the gondola, Lunardi failed to do up the lacings of the gondola door. As the balloon sailed away over Picadilly The beautiful Mrs Sage was on all fours re-threading the lacings to close the door.

Watercolour sketch by Cordy, a spectator, showing Lunardi's second balloon carrying George Biggin and Mrs Sage

The flight followed the line of the Thames westwards finally landing heavily in Harrow on the Hill where the balloon damaged a hedge and gouged a strip through the middle of an uncut hayfield, leaving the farmer ranting abuse and threats. The honour of the first female aeronaut was saved by the young gentlemen from Harrow school who had a whip-round to pay off the farmer and then carried Mrs Sage bodily, in triumph, to the local pub. Mrs. Sage later published her experience as Britain's first female aeronaut, an account which realized two printings.

Published on June 29, 2011 02:25

June 27, 2011

Meet Mrs. Vesey

Copyright National Portrait Gallery

Copyright National Portrait Gallery

Elizabeth Vesey was the daughter of Sir Thomas Vesey, Bishop of Ossory. She first married William Handcock and then Agmondisham Vesey, M.P., Accountant-General of Ireland. She was one of the Bluestocking Circle, along with Mrs. Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Carter and Fanny Burney. The following excerpt refers to the botanist Benjamin Stillingfleet (1702-71), who was welcomed at one of Elizabeth Montagu's salons even though he had arrived absent-mindedly wearing the blue woollen stockings normally worn by working men, instead of the more formal white silk, hence another theory on how the term "blue stocking" was coined.

From Mrs. Montagu by R. Huchon

. . . . Stillingfleet had taken refuge in the cultivation of his garden, which gave him health, and in the study of botany and harmony, which procured him some pleasure. He was often seen at Bath or about town, doubtless stooping in his gait and plunged in his mildly pessimistic thoughts. His accomplishments as a scholar and a wit made him a favourite with Mrs Montagu and the other learned ladies. One day, about 1750, he was at Bath, and received an invitation to "a literary meeting at Mrs Vesey's." He "declined to accept it," Mme d'Arblay informs us, "from not being, he said, in the habit of displaying a proper equipment for an evening assembly. 'Pho, pho" cried Mrs Vesey, with her wellknown, yet always original simplicity, while she looked inquisitively at him and his accoutrement, "don't mind dress! Come in your blue stockings!" With which words, humorously repeating them as he entered the apartment of the chosen coterie, Mr Stillingfleet claimed permission to appear according to order. And those words ever after were fixed in playful stigma upon Mrs Vesey's associations." It seems a confirmation of this account that, on 13th November 1756, a friend of Mrs Montagu's should write to her that "Monsey," the physician of Chelsea Hospital, "swears he will make out some story of you and Stillingfleet before you are much older; you shall not keep blew stockings at Sandleford for nothing." And Mrs Montagu herself, in the following March, having mentioned Stillingfleet in a letter to Monsey, said of him: "I assure you our old philosopher is so much a man of pleasure, he has left off his old friends and his blue stockings, and is at operas and other gay assemblies every night." Stillingfleet and his "blue stockings" there-fore became interchangeable terms among his acquaintances. As Boswell observes : "Such was the excellence of his conversation, that his absence was felt as so great a loss that it used to be said: We can do nothing without the blue stockings; and thus by degrees the title was established." Wherever Stillingfleet appeared, there were the Blue Stockings. By a very natural process, the name extended from Mrs Vesey's parties to those of Mrs Montagu and others. It even crossed the Channel at the end of the century.

[image error] Benjamin Stillingfleet Since the institution and its " title" in all probability originated with Mrs Vesey, it would be unjust to pass her over in silence. She formed a strong contrast with Mrs . Montagu in her disposition and manners. She seemed "of imagination all compact,'' and her friends had affectionately nicknamed her "the Sylph," for, like an "etherial" being, she lived and thought "in a world of her own." In her actual work-a-day life she was none too happy. Fondly attached to her second husband, Agmondesham Vesey, of Lucan, near Dublin, "for many years a member of the Irish House of Commons and Comptroller and Accountant-General for Ireland," she had not succeeded in fixing his affections. "He has many amiable qualities," Mrs Carter said in 1774, "and would have many more if he formed his standard of action from his own mind, for I am inclined to think he is not vicious so much from inclination as from the example of the world. If it was a fashionable thing for wits and scholars and lord - lieutenants and other distinguished personages to be true to their wives, probably our friend would not have found him an unfaithful husband.'' This disappointment had doubtless enhanced Mrs Vesey's flightiness and her dissatisfaction with the things of this world: "She scarcely ever enjoys any one object," Mrs Carter wrote to Mrs Montagu, "from the apprehension that something better may possibly be found in another. It is really astonishing to see how this restless pursuit counteracts all the feelings of her amiable and affectionate heart. There are few things, I believe, that she loves like you and me; yet, when she is with us, she finds that you and I, not being absolute divinities, have no power of bestowing perfect happiness, and so from us she flies away, to try if it is to be met with at an assembly or an opera."1 Ever ingenious at difficulties and little distresses, she lived in "a perpetual forecast of disappointment." One day she fancied that she was losing her senses, or else she felt her memory going and her power of expressing herself decreasing. The joys of friendship were spoilt for her by the bitter thought of their transitoriness. "Is it reasonable," Mrs Carter exclaimed on reading her complaints, "to wish to reject the possession of any real good, merely because it may happen not to be a perpetuity?" She had "a mind formed for doubt," she said of herself, and her bias towards scepticism, though undecided, alarmed her pious friends by its intermittent recurrence.

. . . . Her fears were so great of the horror, as it was styled, of a circle, from the ceremony and awe which it produced, that she pushed all the small sofas, as well as chairs, pell mell about the apartments, so as not to leave even a zigzag path of communication free from impediment: and her greatest delight was to place the seats back to back, so that those who occupied them could perceive no more of their nearest neighbour than if the parties had been sent into different rooms: an arrangement that could only be eluded by such a twisting of the neck as to threaten the interlocutors with a spasmodic affection.

But what most contributed to render the scenes of her social circle nearly dramatic in comic effect, was her deafness. . . . She had commonly two or three or more ear-trumpets hanging to her wrists, or slung about her neck, or tost upon the chimney-piece or table. The instant that any earnestness of countenance or animation of gesture struck her eye, she darted forward trumpet in hand to inquire what was going on, but almost always arrived at the speaker at the moment that he was become, in his turn, the hearer. And after quietly listening some minutes, she would gently utter her disappointment by crying: ' Well, I really thought you were talking of something.' And then, though a whole group would hold it fitting to flock around her, and recount what had been said, if a smile caught her roving eye from any opposite direction, the fear of losing something more entertaining would make her beg not to trouble them, and again rush on the gayer talkers. But as a laugh is excited more commonly by sportive nonsense than by wit, she usually gleaned nothing from her change of place and hastened therefore back to ask for the rest of what she had interrupted. But generally finding that set dispersing or dispersed, she would look around her with a forlorn surprise and cry: "I can't conceive why it is that nobody talks to-night. I can't catch a word." Yet with all these peculiarities Mrs Vesey was eminently amiable, candid, gentle and even sensible, but she had an ardour to know whatever was going forward and to see whoever was named, that kept her curiosity constantly in a panic, and almost dangerously increased the singular wanderings of her imagination.

Mrs. Vesey died in 1789.[image error]

Copyright National Portrait Gallery

Copyright National Portrait GalleryElizabeth Vesey was the daughter of Sir Thomas Vesey, Bishop of Ossory. She first married William Handcock and then Agmondisham Vesey, M.P., Accountant-General of Ireland. She was one of the Bluestocking Circle, along with Mrs. Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Carter and Fanny Burney. The following excerpt refers to the botanist Benjamin Stillingfleet (1702-71), who was welcomed at one of Elizabeth Montagu's salons even though he had arrived absent-mindedly wearing the blue woollen stockings normally worn by working men, instead of the more formal white silk, hence another theory on how the term "blue stocking" was coined.

From Mrs. Montagu by R. Huchon

. . . . Stillingfleet had taken refuge in the cultivation of his garden, which gave him health, and in the study of botany and harmony, which procured him some pleasure. He was often seen at Bath or about town, doubtless stooping in his gait and plunged in his mildly pessimistic thoughts. His accomplishments as a scholar and a wit made him a favourite with Mrs Montagu and the other learned ladies. One day, about 1750, he was at Bath, and received an invitation to "a literary meeting at Mrs Vesey's." He "declined to accept it," Mme d'Arblay informs us, "from not being, he said, in the habit of displaying a proper equipment for an evening assembly. 'Pho, pho" cried Mrs Vesey, with her wellknown, yet always original simplicity, while she looked inquisitively at him and his accoutrement, "don't mind dress! Come in your blue stockings!" With which words, humorously repeating them as he entered the apartment of the chosen coterie, Mr Stillingfleet claimed permission to appear according to order. And those words ever after were fixed in playful stigma upon Mrs Vesey's associations." It seems a confirmation of this account that, on 13th November 1756, a friend of Mrs Montagu's should write to her that "Monsey," the physician of Chelsea Hospital, "swears he will make out some story of you and Stillingfleet before you are much older; you shall not keep blew stockings at Sandleford for nothing." And Mrs Montagu herself, in the following March, having mentioned Stillingfleet in a letter to Monsey, said of him: "I assure you our old philosopher is so much a man of pleasure, he has left off his old friends and his blue stockings, and is at operas and other gay assemblies every night." Stillingfleet and his "blue stockings" there-fore became interchangeable terms among his acquaintances. As Boswell observes : "Such was the excellence of his conversation, that his absence was felt as so great a loss that it used to be said: We can do nothing without the blue stockings; and thus by degrees the title was established." Wherever Stillingfleet appeared, there were the Blue Stockings. By a very natural process, the name extended from Mrs Vesey's parties to those of Mrs Montagu and others. It even crossed the Channel at the end of the century.

[image error] Benjamin Stillingfleet Since the institution and its " title" in all probability originated with Mrs Vesey, it would be unjust to pass her over in silence. She formed a strong contrast with Mrs . Montagu in her disposition and manners. She seemed "of imagination all compact,'' and her friends had affectionately nicknamed her "the Sylph," for, like an "etherial" being, she lived and thought "in a world of her own." In her actual work-a-day life she was none too happy. Fondly attached to her second husband, Agmondesham Vesey, of Lucan, near Dublin, "for many years a member of the Irish House of Commons and Comptroller and Accountant-General for Ireland," she had not succeeded in fixing his affections. "He has many amiable qualities," Mrs Carter said in 1774, "and would have many more if he formed his standard of action from his own mind, for I am inclined to think he is not vicious so much from inclination as from the example of the world. If it was a fashionable thing for wits and scholars and lord - lieutenants and other distinguished personages to be true to their wives, probably our friend would not have found him an unfaithful husband.'' This disappointment had doubtless enhanced Mrs Vesey's flightiness and her dissatisfaction with the things of this world: "She scarcely ever enjoys any one object," Mrs Carter wrote to Mrs Montagu, "from the apprehension that something better may possibly be found in another. It is really astonishing to see how this restless pursuit counteracts all the feelings of her amiable and affectionate heart. There are few things, I believe, that she loves like you and me; yet, when she is with us, she finds that you and I, not being absolute divinities, have no power of bestowing perfect happiness, and so from us she flies away, to try if it is to be met with at an assembly or an opera."1 Ever ingenious at difficulties and little distresses, she lived in "a perpetual forecast of disappointment." One day she fancied that she was losing her senses, or else she felt her memory going and her power of expressing herself decreasing. The joys of friendship were spoilt for her by the bitter thought of their transitoriness. "Is it reasonable," Mrs Carter exclaimed on reading her complaints, "to wish to reject the possession of any real good, merely because it may happen not to be a perpetuity?" She had "a mind formed for doubt," she said of herself, and her bias towards scepticism, though undecided, alarmed her pious friends by its intermittent recurrence.

. . . . Her fears were so great of the horror, as it was styled, of a circle, from the ceremony and awe which it produced, that she pushed all the small sofas, as well as chairs, pell mell about the apartments, so as not to leave even a zigzag path of communication free from impediment: and her greatest delight was to place the seats back to back, so that those who occupied them could perceive no more of their nearest neighbour than if the parties had been sent into different rooms: an arrangement that could only be eluded by such a twisting of the neck as to threaten the interlocutors with a spasmodic affection.

But what most contributed to render the scenes of her social circle nearly dramatic in comic effect, was her deafness. . . . She had commonly two or three or more ear-trumpets hanging to her wrists, or slung about her neck, or tost upon the chimney-piece or table. The instant that any earnestness of countenance or animation of gesture struck her eye, she darted forward trumpet in hand to inquire what was going on, but almost always arrived at the speaker at the moment that he was become, in his turn, the hearer. And after quietly listening some minutes, she would gently utter her disappointment by crying: ' Well, I really thought you were talking of something.' And then, though a whole group would hold it fitting to flock around her, and recount what had been said, if a smile caught her roving eye from any opposite direction, the fear of losing something more entertaining would make her beg not to trouble them, and again rush on the gayer talkers. But as a laugh is excited more commonly by sportive nonsense than by wit, she usually gleaned nothing from her change of place and hastened therefore back to ask for the rest of what she had interrupted. But generally finding that set dispersing or dispersed, she would look around her with a forlorn surprise and cry: "I can't conceive why it is that nobody talks to-night. I can't catch a word." Yet with all these peculiarities Mrs Vesey was eminently amiable, candid, gentle and even sensible, but she had an ardour to know whatever was going forward and to see whoever was named, that kept her curiosity constantly in a panic, and almost dangerously increased the singular wanderings of her imagination.

Mrs. Vesey died in 1789.[image error]

Published on June 27, 2011 23:47

A Note From Victoria

I'm back in the US after my trip to Europe; I will be at the Romance Writers of America meeting in New York City all this week. I had hoped to post about some of my experiences in Portugal, Spain, France and, of course, Merrie Olde England, but I have run out of time before preparing for RWA and the meeting of the Beau Monde Chapter where I will present a power-point program on The Battle of Waterloo and our trip to the 195th anniversasry last year (2010).

[image error]

I am eager to tell everyone about all my experiences, from visiting the tomb of General Sir John Moore in A Corunna, Spain

[image error]

to sitting in the mayor's chair in Windsor when I spent a wonderful day with our good friend and Windsor expert Hester Davenport.

[image error]

I have many tales to tell and pictures to show about my experiences and my research. One thing that has become even more meaningful to me since I got back was seeing the Ai Weiwei Chinese horoscope sculptures at Somerset House in London. Now that he has been released from detention in China, I am really happy I visited his work, which made me sad at the time.

[image error]

Now, a confession. I had a nasty cold much of the trip. I hope it didn't clip my wings too much, but I would have had a much better time if I had been hale and hearty. I took lot of decongestants which helped immensely, but gave me a sort of foggy feeling. Nevertheless, I am glad to say I saw the Queen twice. My photo from Trooping the Colour below.

[image error] [image error]

Above is a newspaper shot of the prettiest hat I've ever seen on the Queen. I did see her, up close if not very personal, but I missed the photo. Thanks again, Hester, for taking me to the "parade."

And finally, to descend from the sublime to the ridiculous, can you believe I managed to be present at a London Naked Bike Ride for the second year in a row? Yes, I walked out of the British Museum and headed for my hotel, only to be stopped by the procession of the group, accompanied by some police and a lot of amused bus riders, down Kingsway. I only took pictures from the rear -- for obvious reasons! I know there's a method to their madeness, but it gets lost in the shuffle!

[image error]

So stick around, I'll get to blogging again in a week or two. Kristine has done a great job of keeping things rolling, so here is a public thank you -- she does the lion's share of the work!! But if she enjoys it half so much as I do, it is more than worthwhile.[image error]

[image error]

I am eager to tell everyone about all my experiences, from visiting the tomb of General Sir John Moore in A Corunna, Spain

[image error]

to sitting in the mayor's chair in Windsor when I spent a wonderful day with our good friend and Windsor expert Hester Davenport.

[image error]

I have many tales to tell and pictures to show about my experiences and my research. One thing that has become even more meaningful to me since I got back was seeing the Ai Weiwei Chinese horoscope sculptures at Somerset House in London. Now that he has been released from detention in China, I am really happy I visited his work, which made me sad at the time.

[image error]

Now, a confession. I had a nasty cold much of the trip. I hope it didn't clip my wings too much, but I would have had a much better time if I had been hale and hearty. I took lot of decongestants which helped immensely, but gave me a sort of foggy feeling. Nevertheless, I am glad to say I saw the Queen twice. My photo from Trooping the Colour below.

[image error] [image error]

Above is a newspaper shot of the prettiest hat I've ever seen on the Queen. I did see her, up close if not very personal, but I missed the photo. Thanks again, Hester, for taking me to the "parade."

And finally, to descend from the sublime to the ridiculous, can you believe I managed to be present at a London Naked Bike Ride for the second year in a row? Yes, I walked out of the British Museum and headed for my hotel, only to be stopped by the procession of the group, accompanied by some police and a lot of amused bus riders, down Kingsway. I only took pictures from the rear -- for obvious reasons! I know there's a method to their madeness, but it gets lost in the shuffle!

[image error]

So stick around, I'll get to blogging again in a week or two. Kristine has done a great job of keeping things rolling, so here is a public thank you -- she does the lion's share of the work!! But if she enjoys it half so much as I do, it is more than worthwhile.[image error]

Published on June 27, 2011 02:00

June 26, 2011

Downton Castle

From the Greville Memoirs

June 26th, (1839) Delbury.— "I rode to Downton Castle on Monday, a gimcrack castle and bad house, built by Payne Knight, an epicurean philosopher, who after building the castle went and lived in a lodge or cottage in the park: there he died, not without suspicion of having put an end to himself, which would have been fully conformable to his notions. He was a sensualist in all ways, but a great and self-educated scholar. His property is now in Chancery, because he chose to make his own will. The prospect from the windows is beautiful, and the walk through the wood, overhanging the river Teme, surpasses anything I have ever seen of the kind. It is as wild as the walk over the hill at Chatsworth, and much more beautiful, because the distant prospect resembles the cheerful hills of Sussex instead of the brown and sombre Derbyshire moors. The path now creeps along the margin, and now rises above the bed of a clear and murmuring stream, and immediately opposite is another hill as lofty and wild, both covered with the finest trees—oaks, ash, and chestnut —which push out their gnarled roots in a thousand fantastic shapes, and grow out of vast masses of rock in the most luxuriant and picturesque manner. Yesterday I came here, a tolerable place with no pretension, but very well kept, not without handsome trees, a,nd surrounded by a very pretty country."

Downton Castle

Downton Castle

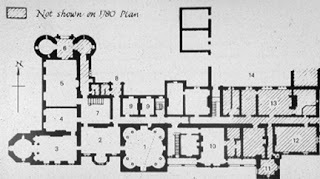

Richard Payne Knight by Sir Thomas Lawrence Richard Payne Knight (1750-1824), was born in 1750 and called Payne after his grandmother, Elizabeth, daughter of Andrew Payne, and wife of Richard Knight (1659-1745), the founder of the Knight family, who acquired great wealth by the ironworks of Shropshire, and settled at Downton, Herefordshire. Being of a weakly constitution, Knight was not sent to school till he was fourteen, and did not begin to learn Greek till he was seventeen. He was not at any university. About 1767 he went to Italy, and remained abroad several years.

Richard Payne Knight by Sir Thomas Lawrence Richard Payne Knight (1750-1824), was born in 1750 and called Payne after his grandmother, Elizabeth, daughter of Andrew Payne, and wife of Richard Knight (1659-1745), the founder of the Knight family, who acquired great wealth by the ironworks of Shropshire, and settled at Downton, Herefordshire. Being of a weakly constitution, Knight was not sent to school till he was fourteen, and did not begin to learn Greek till he was seventeen. He was not at any university. About 1767 he went to Italy, and remained abroad several years.Knight again visited Italy in 1777, and from April to June of that year was in Sicily in company with Philipp IIackert,the German painter, and Charles Gore. When in Italy Knight spent much time at Naples, where his friend Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803) was the British envoy. About 1764 Knight had inherited the estates at Downton, Herefordshire. He ornamented the grounds, and there erected from his own designs a stone mansion in castellated style. Knight invited Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton to Downton Castle in 1802 and also owned a house in Soho Square, London, where he used one of the large rooms as his museum. In 1780 he became M.P. for Leominster, and from 1784 to 1806 sat for Ludlow

Knight died at his house in Soho Square, on 23 April 1824, of 'an apoplectic affection' (Gent. Mag. 1824, pt. ii. p. 185). He was buried in Wormesley Church, Herefordshire, where there is a monument to him, with a Latin epitaph by Cornewall, bishop of Worcester.

His Downton estate passed to his brother, Thomas Andrew Knight. He made to the British Museum, of which he had been Townley trustee since 1814, the munificent bequest of his bronzes, coins, gems, marbles, and drawings. The collection was valued at the time at sums varying from 30,000/. to 60,000/. The acquisition of the bronzes and coins immensely strengthened the national collection. The trustees of the British Museum printed and published in 1830 Knight's own manuscript catalogue of the coins, with the title 'Nummi Veteres.'[image error]

Published on June 26, 2011 00:56

June 24, 2011

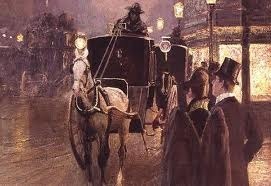

London Cab Horses

From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon 1893)

. . . . Our cab horses are generally Irish, many of them being shipped from Waterford. They come over unshod, in order that they may do no damage, and to keep them quiet they have their lips tied down; and what with this lip-tying, and the sea passage, and the change of climate, it takes them about eight weeks to get into working order, during which they are gradually drilled into shape, first in double harness and then in single harness, round the squares and quiet thoroughfares.

As a rule, they are four years old when they arrive, they cost 30L, they last only three years, and they are then sold to go into the tradesman's cart; but horses are rising in value, and cost more to buy and fetch more to sell than they used to do. This, of course, refers to the bulk of the horses, which, as in the omnibus service, are mostly mares. There are some that cost more, some that cost less; some that last longer, some that do not last as long; and on the cab-rank there is a fair sprinkling of British horses and a few foreigners, but the thoroughbreds of whom we have heard are as rare as the doctors, warriors, and members of the Athenaeum Club who are said to drive them.

A cab horse is well fed; hansom horses average a sack of corn each a week; and they want it, for in the six days during the season they are driven over two hundred miles. There is nothing out of the way in a day's work of forty miles; and this with a weight of half a ton behind, including the cab and driver, but not the passengers. The way in which the horse is worked varies in different yards and with different men. There are over 3,500 cab-owners in London, and as some of them own a hundred and more cabs, there must be a large number who have but one or two cabs, and perhaps two or three horses, when the horses have a hard time of it. Many are worked on the 'one horse power' principle, in which the cab, generally a four-wheeler, goes out at eight in the morning and comes back at eight at night. The fourwheelers that frequent the railway stations have two horses, the first going out at seven in the morning and returning about two in the afternoon, the second going out to stay at the station till ten, and then perhaps loitering about the theatres with a view to picking up a last fare.

When a horse is bought by the cab-master it is occasionally numbered, but oftener named from some trivial circumstance connected with its purchase, or from some event chronicled in the morning newspapers. A whole chapter might be written on the names of the London cab horses, which are assuredly more curious than elegant. Three horses we know of bought on a hot day were Scorch, Blaze, and Blister; three others bought on a dirty morning were Mud, Slush, and Puddle; two brought home in a snowstorm were named Sleet and Blizzard; four that came in the rain were Oilskin, Sou'-wester, Gaiters, and Umbrella. Even the time of day has furnished a name, and Ten o'clock, Eight-sharp, and Nine-fifteen have been met with . . . Some horses are named from the peculiarities of the dealer or his man, and in one stable there were at one time Curseman, Sandyman, Collars, Necktie, Checkshirt, and Scarfpin. The political element is, of course, manifest, and in almost every stable there are Roseberies and Randies, Salisburies and Gladstones, Smiths and Dizzies. Some stables are all Derby winners, some all dramas, some all songs, some all towns. It is the exception for a horse to be named after any peculiarity of its own, unless it be an objectionable one; and it would never do to give it a Christian name, with or without a qualifying adjective, which might lead to its being mistaken for one of the men in the yard.

The favourite colour for a cab horse is brown; the one least sought after is grey. A grey horse will not do in a hansom, unless for railway work where the cabs are taken in rotation and the quality or colour of the horse is of no consequence. Why clubland should object to grey horses is not known, but the fact remains that a man with a grey horse will get fewer fares with him than with a brown one. One explanation is that the light hairs float off and show on dark clothes, but this is hardly satisfying, and it seems safer to put the matter down to fashion. Anyhow, a hansom cabman will not take out a grey horse if he can help it, unless it be an exceptionally 'gassy' one, gassy being 'cabbish' for showy. But not so a four-wheeler man; if he can have a grey horse he will, the reason being that if ever a housemaid goes for a cab she will, if she has a choice, pick out the grey horse. At least, so says the trade, which may, of course, be prejudiced or romancing; but the prejudice or the romance is known all over London.

London has 600 cabstands, exclusive of those in the City and on private ground, such as the railway stations. A few of these are always full; a few have never had a cab on them even though they may have existed for years. The 600 cabstands on an average afford accommodation for eleven vehicles each. The rest of the cabs are either carrying passengers or else plying empty along such streets as Piccadilly, where they are a nuisance to all but those who want cabs. The same thing may, however, be said of the cabstands, and, considering the convenience that ' crawlers' afford, it is only the very strenuous reformer who would abolish them entirely, if it were possible to do so.

Out of the 15,000 cabmen, about 2,000 are convicted every year for drunkenness, cruelty, wilful misbehaviour, loitering, plying, obstruction, stopping on the wrong side of the road, delaying, leaving their cabs unattended, &c, &c. The cabman who 'knows his business best' is the one who can crawl judiciously without getting into trouble with the police, resulting for a first offence in the famous 'two-and-six and two,' which means half-a crown fine and a florin costs.

At many of the stands there is a 'shelter,' which is much larger inside than a glance at the exterior would lead one to suppose. The shelters are generally farmed from the Shelter Fund Society by some old cabman. They are the cabman's restaurants, and the cabman, as a rule, is not so much a large drinker as a large eater. At One shelter lately the great feature was boiled rabbit and pickled pork at two o'clock in the morning, and for weeks a small warren of Ostenders was consumed nightly.

The two-wheeler improves every year. There are many hansoms now in London as good in every way as private carriages, and these will often have a fiftyguinea horse in their shafts. The four-wheeler improves but microscopicr.lly, and, though it becomes no worse than it used to be, it touches a depth which is by no means desirable. Most cabs are varnished twice a year, some are varnished but once, and that, of course, is just before inspection day, when the new annual licence is applied for. On that morning many a newlyvarnished mockery will journey gingerly to Clerkenwell, and just satisfy the inspector's lenient eye, returning triumphantly with the inside and outside plates and the stencilled certificate on its back, which show that the vehicle has passed muster, and that the owner has paid 21. for a licence to work it in the London streets. Besides the 21., the owner has to pay fifteen shillings carriage duty to Somerset House; and, for a licence and the badge to drive, the cabman has to pay to the police five shillings.

The cabman has to pass an examination as well as the vehicle, but the vehicle is examined every year, while the cabman is only examined once, and then not in personal appearance, though there may be a bias that way, but in an elementary knowledge of London topography. The knowledge required is not very great, and 1,500 candidates apply in a year, but it is interesting to note that out of every 100 candidates 34 are 'ploughed'—a much higher percentage of rejections than exists among the vehicles.

The cabman takes his licence to the owner whom he desires to make his 'master.' He takes the cab out on trust, leaving his licence as a deposit so long as he remains in the same employment. The engagement is terminable at any time, and when the man changes masters his old master has to fill in on the back of his licence the length of time he has been in his service. At the end of the year the man takes the endorsed licence accounting for his year's work to New Scotland Yard, and there gets a clean one covering another twelve months.

The amount paid by the man for the day's hire varies with the vehicle, the master, and the season. It is much less really than it is nominally, owing to the numerous occasions on which allowances are made for bad luck and bad weather. Continuous wet is not cabmen's weather; what they like is a showery day, or, what is better, a fine morning and a wet afternoon, or a series of scorching hot days when people find the other means of conveyance too stuffy for comfort. Although the amount is frequently stated to be more, the average for hansoms during the last year over several yards was nine shillings for the first three months in the year, then a rise every week of a shilling a day to the end of May, when it remained at the maximum of eighteen shillings till the second week in June, when it dropped a shilling a week down to the nine shillings at which it will remain for the rest of the year. The height of the London cab season is thus from the Derby week to the Ascot week, the one day being the Thursday after the Derby. If you wish to go to the Derby in a hansom you pay 31., of which 11. is extra profit, it being estimated that the man would have taken 21. if he remained in London. And, curiously enough, the distance to and from Epsom is the average day's journey of a London cab horse.

[image error]

Published on June 24, 2011 00:02

June 22, 2011

More on the Bahamas

While we were in Nassau recently, Brooke and I decided to hit the beach and play in the frigid surf, while others who shall remain nameless took the opportunity to grab forty winks.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

You'll note that while there were many people on the beach, the water was empty. Brrrr. Brooke and I dove in and it wasn't long before I had been face-planted in the sand by a rogue wave/the incoming tide. With literally a mouth and bathing suit full of sand, I went to wash off, when I encountered a new friend.

[image error]

Regular readers of this blog will recall that I met an entertaining French crow when in Paris last year. This Bahamian dove had all the sauciness of his French counterpart, as well as an eye for the ladies.

[image error]

"Yeah, Mon, dat's one good looking woman. Rockin' legs, Mama!"

[image error]

"And here's another. Work it, girl! Dose buns truly be mighty fine."

[image error]

"Is dat suppose to be a bathing suit? I heard of thongs, but dat's takin' it to the extreme. Not dat I'm complaining. Just sayin . . . . "

[image error]

"Oh, Mon, the wife be coming back. Best pull me eyes back in my head and pretend I been looking at these water lilies all along. Look here, sweetheart, I found you a Monet garden almost a gorgeous as you are . . . I been missing you while you was gone. What took you so long?"

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

You'll note that while there were many people on the beach, the water was empty. Brrrr. Brooke and I dove in and it wasn't long before I had been face-planted in the sand by a rogue wave/the incoming tide. With literally a mouth and bathing suit full of sand, I went to wash off, when I encountered a new friend.

[image error]

Regular readers of this blog will recall that I met an entertaining French crow when in Paris last year. This Bahamian dove had all the sauciness of his French counterpart, as well as an eye for the ladies.

[image error]

"Yeah, Mon, dat's one good looking woman. Rockin' legs, Mama!"

[image error]

"And here's another. Work it, girl! Dose buns truly be mighty fine."

[image error]

"Is dat suppose to be a bathing suit? I heard of thongs, but dat's takin' it to the extreme. Not dat I'm complaining. Just sayin . . . . "

[image error]

"Oh, Mon, the wife be coming back. Best pull me eyes back in my head and pretend I been looking at these water lilies all along. Look here, sweetheart, I found you a Monet garden almost a gorgeous as you are . . . I been missing you while you was gone. What took you so long?"

[image error]

Published on June 22, 2011 23:51

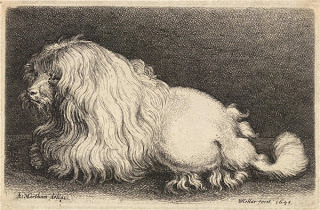

Paying Occupations for Gentlewomen

From Cassell's Family Magazine - 1896

I would mention poodle-clipping as an agreeable and remunerative profession in which a few gentlewomen might engage. In an article on " New Paid Occupations for Women '' published in Cassall's Family Magazine about a year ago, I spoke of a new employment, then recently started in New York—that of brushing, combing and exercising pet dogs, and have since heard that the occupation has been taken up by some English girls with great success. There are so many pet dogs in London that there is chance for much competition in this matter, and it is certainly a very healthy and agreeable sort of outdoor work. The business of poodle-clipping for women, however, is one that, so far as I know, has never been attempted either in the United States or in England, and I would suggest to some enterprising gentlewoman that she be the first to engage in it. The idea occurred to me about two months ago, when on making a morning call I found a friend wielding a pair of clippers on her own poodle, which she explained had been previously subjected to careless if not cruel treatment by his male barber, who charged twelve shillings and sixpence for his mutilations. In recommending poodle-clipping as a suitable employment for women, I am able to vouch for its practicability, because I have since made the experiment myself on a poodle, and have had the pleasure of hearing my handiwork highly commended.

The Poodle, from a 17th century engraving

The Poodle, from a 17th century engraving Poodles are now so fashionable and are so frequently to be seen in the streets and parks that I need not describe the " costumes'' affected by them, but it is not generally known that the machine which clips and shaves them so fantastically and artistically may be purchased in a small size suitable for ladies' use for seven shillings and sixpence, and that a pair of nippers for cutting their nails is to be bought for half-a-crown. These two things are all that are required for starting in business. The shopman from whom the clippers are purchased (they are to be bought at any of the general stores) will explain all that it is necessary to know as to the manner of using the machine, which is an affair greatly resembling a pair of scissors, composed of two rows of sharp teeth or combs and worked precisely on the scissors principle. If, however, one is fearful to begin the work without having first seen it done, it is an easy matter to gain admittance to a dog fancier's and see a poodle clipped. The gentlewoman must, of course, be clever with her fingers and have something of an artistic eye in order to clip a dog in the prevailing style, which demands " ruffles " and " shoes and stockings " and " mustachios." The nail nippers are only an extra strong pair of scissors, which must be used in such a way as to cut off only the tip end of the nail in order to avoid hurting the dog.

The next thing is to get the poodles, which should be an easy matter if a well-worded advertisement is inserted in the newspaper columns where dogs and horses are announced for sale. This department of the paper is much better than the ordinary " situations wanted " column. It would also be well to advertise in a popular ladies' weekly paper, or, better, in a periodical devoted to the interests of household pets. Let the advertisement state that a gentlewoman who is fond of and kind to animals is prepared to visit ladies' houses for poodle-clipping. The price should be stated as being lower than that charged by ordinary dog fanciers, and as there are probably none who would undertake the work for less than half-a-guinea, let the lady poodle-clipper shave dogs for seven shillings and sixpence each. The work would require no setting up in a shop and no tools except those I have mentioned. The owner of the dog will have a large kitchen table which is to be used as the " barber's chair " during the clipping process, and the person who does the clipping will need a large print apron.

There is room in London for at least six or eight gentlewomen as dog-clippers, and as the up-to-date poodle needs clipping every month or six weeks, there is no reason why such women should not find steady employment. The time required for clipping one dog is from three to four hours. For women who are fond of animals—and kindness to animals is one of the most pleasing traits in the Englishwoman's character—this work should be neither difficult nor disagreeable, and it is quite within the bounds of practicability, which is more than can be said for many other occupations recommended to gentlewomen.[image error]

Published on June 22, 2011 00:13

June 20, 2011

Atlantis Resort, Bahamas

Last week, I went with my mother, Rose, and my daughter, Brooke, to the Atlantis Resort in Nassau, Bahamas. We enjoyed a few days of sun, water and food, not to mention marine life.

[image error]

Our hotel room had gorgeous views of both the ocean and the shark pool, which was just beneath our balcony.

[image error] [image error]

It didn't take long for us to begin exploring the grounds, where Brooke soon came across a waterfall.

[image error]

And yet another shark pool - this one with the species that bite. Here they are circling for food.

[image error]

We spent a good portion of our time circling for food, as well. Here are Rose and Brooke at the buffet breakfast. The nearby windows offered us the view of the feeding sharks. [image error]

One night we went to Carmine's, where the portions are huge, rather than delicious.

[image error]

Above is the fried zucchini appetizer, which was huge and tasty. Below was the veal parm which was huge and tough.

[image error]

Brooke enjoyed her rack of lamb at the upscale Bahamian Club restaurant.

[image error]

[image error]

I chowed down on massive prime rib served on a sizzling platter. Dr. Atkins would have been proud.

[image error]

We took some time out from eating in order to venture into town to the straw market, where piracy is still alive and well - knock-off designer bags are the hot items here. I bought three.

[image error]

I should confess that the only nod I gave to British history during the trip was when we passed by Parliament Square in the taxi.

[image error]

Needless to say, a good time was had by all. More on our Bahamian adventures soon.

[image error]

[image error]

Our hotel room had gorgeous views of both the ocean and the shark pool, which was just beneath our balcony.

[image error] [image error]

It didn't take long for us to begin exploring the grounds, where Brooke soon came across a waterfall.

[image error]

And yet another shark pool - this one with the species that bite. Here they are circling for food.

[image error]

We spent a good portion of our time circling for food, as well. Here are Rose and Brooke at the buffet breakfast. The nearby windows offered us the view of the feeding sharks. [image error]

One night we went to Carmine's, where the portions are huge, rather than delicious.

[image error]

Above is the fried zucchini appetizer, which was huge and tasty. Below was the veal parm which was huge and tough.

[image error]

Brooke enjoyed her rack of lamb at the upscale Bahamian Club restaurant.

[image error]

[image error]

I chowed down on massive prime rib served on a sizzling platter. Dr. Atkins would have been proud.

[image error]

We took some time out from eating in order to venture into town to the straw market, where piracy is still alive and well - knock-off designer bags are the hot items here. I bought three.

[image error]

I should confess that the only nod I gave to British history during the trip was when we passed by Parliament Square in the taxi.

[image error]

Needless to say, a good time was had by all. More on our Bahamian adventures soon.

[image error]

Published on June 20, 2011 23:34

The Strange Death of . . . .

From The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 79, Part 1

From The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume 79, Part 1Deaths. 1808

March 19. Aged 18, Miss Bradshaw, of Yarwell, near Wansford. She had been abruptly informed of the death of a younger brother at Crowland (who had been on a visit to her but a few days before); which had such an effect on her as to occasion her death in a few hours.

Aged 70, Mrs. Edwards, an infirm widow lady, residing at the house of Mr. Aldrich, postmaster, at Enstone, Co. Oxford. She was burnt to death in her own apartment. When discovered, her body was consumed to a cinder; and so rapid was the progress of the flames, that very little of the furniture could be saved, and the house was burnt to the ground. It is supposed the accident was occasioned by Mrs. F.'s cloaths catching fire.

22. Mr. Ricketts, who fought a duel on Lemon common, Herts, on the 13th, with a Mr. Wright, and who was wounded in the thigh. He died in consequence of a mortification, having refused to undergo amputation of the limb.

23. Found drowned in the Thames, above Vauxhall, J. Meyhurst, an Italian, butler to Mrs. Seret, of Chelsea. He had been missing several days; and for some time previous had appeared in a desponding way, which proves to have arisen from an embarrassment in his accounts. Upwards of 20/. in notes and cash were found in his pockets.

Aged 57, Mr. Ingram, tailor, of Northampton. He was attending a meeting assembled for religious exercise early in the morning, a practice which he had observed with punctuality for some years, when he suddenly dropped down, and expired without a struggle. By some expressions which fell from him the day previous to his decease, he appeared to have taken his leave of the world, and to have had some presentiment of the near approach of his dissolution.

25. Mr. Neighbour, a farmer, near Maidenhead. On his return home, after spending the evening at the Bell with some friends, be lost his way, the night being dark, fell into the Thames, and was found in it, about a fortnight afterwards, near Windsor.

27. — Bates, a labouring man. While going to his work, at Hoxton, and talking cheerfully to a fellow-labourer, he dropped down, and instantly expired.

29. Isaac Edney, a lad residing in the Holloway near Bath, was found smothered in the snow. He had been driving a horse and cart; and the animal being prevented from proceeding by the great depth of snow, it is supposed he had alighted to endeavour to extricate it, but, unable either to effect his purpose or regain his seat, perished.

A child, the eldest of five, belonging to — Higgs, a wool-comber at Leicester, being left in the care of other children whilst the parents went to market, incautiously fell asleep with a candle in her lap, and was so miserably burnt as to occasion her death in a few hours.

In the Newington-road, Miss Charlotte Hachel, a young lady from Lincolnshire; whose death was occasioned by failing off the outside of a stage-coach, in consequence of the sudden jerk of the vehicle.

April 8 In Charlotte-str. Portland-place, Lieut Col. Henry Knight, on half-pay. In consequence of a nervous fever, he had become deranged, aud had been attended by Dr. Simmons; but was thought better, and. was living again with his family, when this morning, during the absence of his servant, he threw himself out of a backroom window, and survived the fall but three quarters of an hour.

April 20 Mr. Isaac Hester, a gentleman of independent property, who resided in Northampton-place, Mary-le-bone-road. His body was found in a Held near Newington, in a putrid state, with the head half severed from it, by some boys who were seeking bird-nests. He had been some in a state of dejection bordering on insanity, and effected his escape on the 9th. It was evident he had commited suicide with a knife, which was found in his band closely grasped.

21. At her residence in Half-moon-street, Piccadilly, Miss Cummins, daughter of a gentleman of fortune in the West Indies, and, with a sister and brother, living at the house of an uncle. She had returned with a party from the Opera the preceding night; and, on retiring to her dressing-room, the candle communicated to her muslin-dress. Her shrieks brought other young persons from the drawing-room to her assistance, but not till her garments were reduced to tinder. She lingered in torture till this evening.

24 Mrs. Ford, of Sidbury, Worcestershire, one of the people called Quakers. Her death was occasioned by circumstances peculiarly distressing: she had taken her child to an eminent surgeon, to have a swelling on the throat lanced; when the operation was about to be performed she fainted through terror, and almost instantaneously expired.

27. By taking laudanum, Mrs. Farwell, a widow lady, of Wilson-buildings, Hampstead-road. The loss of her husband, who died about twelve months since, and that of a daughter about a fortnight ago, preyed on her mind, and is supposed to have led to the melancholy event.

30 Aged 103, Richard Williams, of Boddewran, in the parish of Honeglwys, co. Anglesea; who had been blind upwards of six years, but whose sight was restored a short time before his death; and he had also four new teeth.

[image error]

Published on June 20, 2011 00:35

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.