Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 141

August 18, 2011

Travels With Victoria: Holland Park

On all my trips to London, I have meant to visit Holland Park, and I fanally made it. Today Holland Park is in the center of town. When it was in its heyday as the gathering place for the grand Whigs in the late 18th and early 19th centuries it was a country house, beyond the boundaries of London and Westminster.

[image error] Holland House, today

Very little of the original house remains after most of it was destroyed in 1940 by German bombs. The remainder, above, was turned into a youth hostel. Elsewhere in the park the Opera Holland Park performances are held outside.

As part of the Open Squares Weekend, June 11-12, 2011, I wanted to visit the garden, a very attractive design for its placement in the midst of a shady park.

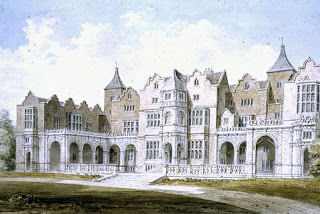

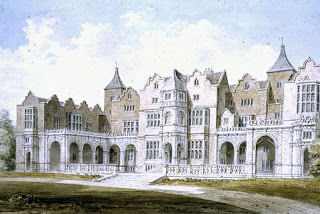

Above is the Jacobean House as it appeared in a drawing of 1812 when it was already 200 years old. First built in 1605 for Sir Walter Cope, it was known as Cope Castle, and occupied 600 acres of land in Kensington about two miles west of London. The house was inherited by Cope's son-in-law, Henry Rich, first Earl Holland, who lost his head to the forces of Parliament in the Civil War. His family regained the estate, now known as Holland House, at the Restoration.

Several generations later, it became the property of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland (1705-1774), who lived there with his wife Caroline Lennox (1723-1774), daughter of the 2nd Duke of Richmond. They had eloped due to the political emnity of the father and prospective son-in-law, as well as considerations of difference the in ages of the couple. Nevertheless, it was a happy marriage, though marred by the tendency of their sons toward dissolute lives.

Caroline Lennox Fox, Lady Holland

Caroline Lennox Fox, Lady Holland

Their story is told in the book The Aristocrats by Stella Tillyard, an account of the lives of the Lennox sisters, later produced for television. Among Caroline's children was the renowned late 18th century politician and stateman Charles James Fox, whose life is full of fascinating contradictions. He was the arch rival of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.

Whig politican Charles James Fox (1749 -1806)

Henry Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840), was traveling in Naples, Italy, when he met Elizabeth Vassall, Lady Webster, wife of Sir Godfrey Webster, 4th Baronet. Baron Holland and Lady Webster fell in love, though she already had borne five children to Webster (3 of whom survived infancy). Webster sought and obtained a divorce on the grounds of adultery, a shocking and rare situation in those days. His estranged wife already had a child with Holland, a son, Charles Richard Fox, who later became a general in the British Army. A few days after the divorce, Baron Holland married Elizabeth; They had 3 more children who lived to adulthood.

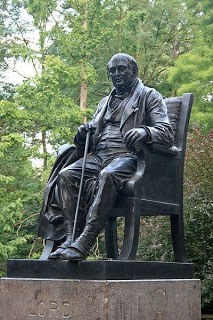

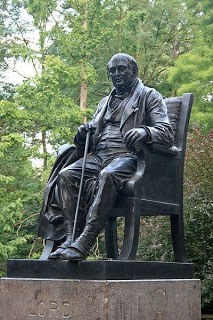

Statue of 3rd Baron Holland in the park.

Statue of 3rd Baron Holland in the park.

Lord and Lady Holland lived at Holland House, and for forty-plus years, they presided over a brilliant social and political salon, despite the fact she had been divorced and was not received at court. All the influential Whigs, including the Prince of Wales, and leading government ministers came to Holland House.

The Gold Cameo Box, shown here at the British Museum, was bequeathed to Lady Holland by Napoleon in 1821, having been a gift from the Pope to Napoleon in 1797. Lord and Lady Holland were supporters and admirers of Napoleon, as were many prominent Whigs.

Henry Edward Fox, 4th Baron Holland, and his wife had no male offspring and thus the Holland title became extinct. The house passed to the Fox-Strangways family, Earls of Ilchester, who also entertained political and social leaders there into the 20th century. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended a ball at Holland House just a few days before it was destroyed.

Searching the library in the bombed out Holland House

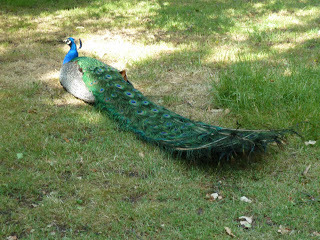

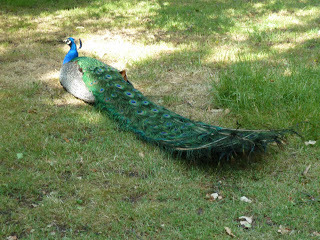

Though there is not much of the house remaining, the park is lovely, home to roaming peacocks among other wildlife. There are also fields for team sports and gently winding walks, often crowded with joggers and strollers.

Exiting the park to the north, the residential area is lovely, with large mansions in white stucco dominating the streets.

Exiting the park to the north, the residential area is lovely, with large mansions in white stucco dominating the streets.

I couldn't decide which side of the street I wanted to choose, so I have delayed the decision! I think either one would do!!

I couldn't decide which side of the street I wanted to choose, so I have delayed the decision! I think either one would do!!

Next post: Recollections of Lord and Lady Holland by Charles Greville

Next on Travels with Victoria: The Gardens of Westminster Abbey[image error]

[image error] Holland House, today

Very little of the original house remains after most of it was destroyed in 1940 by German bombs. The remainder, above, was turned into a youth hostel. Elsewhere in the park the Opera Holland Park performances are held outside.

As part of the Open Squares Weekend, June 11-12, 2011, I wanted to visit the garden, a very attractive design for its placement in the midst of a shady park.

Above is the Jacobean House as it appeared in a drawing of 1812 when it was already 200 years old. First built in 1605 for Sir Walter Cope, it was known as Cope Castle, and occupied 600 acres of land in Kensington about two miles west of London. The house was inherited by Cope's son-in-law, Henry Rich, first Earl Holland, who lost his head to the forces of Parliament in the Civil War. His family regained the estate, now known as Holland House, at the Restoration.

Several generations later, it became the property of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland (1705-1774), who lived there with his wife Caroline Lennox (1723-1774), daughter of the 2nd Duke of Richmond. They had eloped due to the political emnity of the father and prospective son-in-law, as well as considerations of difference the in ages of the couple. Nevertheless, it was a happy marriage, though marred by the tendency of their sons toward dissolute lives.

Caroline Lennox Fox, Lady Holland

Caroline Lennox Fox, Lady HollandTheir story is told in the book The Aristocrats by Stella Tillyard, an account of the lives of the Lennox sisters, later produced for television. Among Caroline's children was the renowned late 18th century politician and stateman Charles James Fox, whose life is full of fascinating contradictions. He was the arch rival of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.

Whig politican Charles James Fox (1749 -1806)

Henry Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840), was traveling in Naples, Italy, when he met Elizabeth Vassall, Lady Webster, wife of Sir Godfrey Webster, 4th Baronet. Baron Holland and Lady Webster fell in love, though she already had borne five children to Webster (3 of whom survived infancy). Webster sought and obtained a divorce on the grounds of adultery, a shocking and rare situation in those days. His estranged wife already had a child with Holland, a son, Charles Richard Fox, who later became a general in the British Army. A few days after the divorce, Baron Holland married Elizabeth; They had 3 more children who lived to adulthood.

Statue of 3rd Baron Holland in the park.

Statue of 3rd Baron Holland in the park.Lord and Lady Holland lived at Holland House, and for forty-plus years, they presided over a brilliant social and political salon, despite the fact she had been divorced and was not received at court. All the influential Whigs, including the Prince of Wales, and leading government ministers came to Holland House.

The Gold Cameo Box, shown here at the British Museum, was bequeathed to Lady Holland by Napoleon in 1821, having been a gift from the Pope to Napoleon in 1797. Lord and Lady Holland were supporters and admirers of Napoleon, as were many prominent Whigs.

Henry Edward Fox, 4th Baron Holland, and his wife had no male offspring and thus the Holland title became extinct. The house passed to the Fox-Strangways family, Earls of Ilchester, who also entertained political and social leaders there into the 20th century. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended a ball at Holland House just a few days before it was destroyed.

Searching the library in the bombed out Holland House

Though there is not much of the house remaining, the park is lovely, home to roaming peacocks among other wildlife. There are also fields for team sports and gently winding walks, often crowded with joggers and strollers.

Exiting the park to the north, the residential area is lovely, with large mansions in white stucco dominating the streets.

Exiting the park to the north, the residential area is lovely, with large mansions in white stucco dominating the streets. I couldn't decide which side of the street I wanted to choose, so I have delayed the decision! I think either one would do!!

I couldn't decide which side of the street I wanted to choose, so I have delayed the decision! I think either one would do!!Next post: Recollections of Lord and Lady Holland by Charles Greville

Next on Travels with Victoria: The Gardens of Westminster Abbey[image error]

Published on August 18, 2011 01:00

August 15, 2011

The Jobmaster's Horse

From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon (1893)

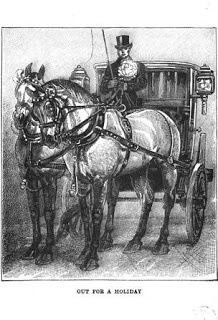

The best horses are, of course, those used for fashionable carriage work. The high-class harness horse comes to London when he is about four years old. He is untrained, undrilled, with all bis troubles to be faced. The young cart-horse is gradually introduced to work on the farm; not so the carriage horse, who is too much of the possibility of a valuable animal to run any risks with. He may fetch 80L; but if he is a handsome, well-built, upstanding state-coach horse, of the kind now so much sought after, he will be cheap at 120L He has to be educated to behave himself like a gentleman; he must learn to stand well—not an easy thing to do—he must know how to back and turn gracefully, how to draw up stylishly at a front door, how to look nice when under window criticism, how to carry his head and lift his feet, and how to work with a companion and be as like him in action as one pea is like another; in short, he has to go through a complete course of deportment, though not of dancing, and he will be a promising pupil if he gets through it in eight months. If he does well and shows a willing mind, it is well with him and he has an easy time of it for years; but if he is tricky or perverse in any way he may have to go to hard labour and spend a twelvemonth in a 'bus. Sometimes that breaks him thoroughly of his bad habits and he returns to carriage work; sometimes, like an habitual criminal, he refuses to amend, and he remains a 'bus horse for life. And herein is the advantage of a miscellaneous business, for if a horse will not do in one branch he may in another.

The new horse is not branded or numbered, but a note is made of his marks, and he is named from a book of names, taking, perhaps, an old name which has been vacant for at least a year; the names being chosen as fitting the particular horse, and not as aiding the memory with regard to the date or circumstance of his purchase, naming from pedigree, as in the case of a racer, being, of course, out of the question. There are many systems of naming; some firms, like Truman & Hanbury, and Spiers & Pond, give the horses names which begin with the same initial all through the year, so that the A's may show the horses bought in 1890, the B's those bought in 1891, the C's those bought in 1892, &c.; others have other plans, but nothing of this systematic sort seems to exist in the livery trade, owing, perhaps, to the possibility of awkward developments in the event of the customer learning the key.

When the horse has passed his drills and been pronounced efficient, he takes his place with eight or nine others in a stable which has its roof thatched inside, so as to keep the temperature equable in summer and winter; and in every one of these stables the horses are as much as possible of the same colour and size, so as to look their best amid their comfortable surroundings. There are fixed travises and no bales for this class of horse, and no peat, but the usual straw, both for the sake of appearance and to save his coat from roughening. He is as well cared for as the plate at a silversmith's, and, like it, is not often so well treated when out on hire. But horses of all grades are nowadays better treated than they used to be, even though there may be deterioration in their quality, which, to say the least of it, is doubtful.

(Doctors) with a consulting practice want a different sort of horse to the humbler general practitioner. The consulting man must have a pair that go fast and well, and cover long distances, and draw up at the door in a style that will inspire the patient and the patient's friends with faith—and move the G.P. to envy. The said G.P. must have a horse that is ready for work at all hours, and looks none the worse for standing about in the rain; in other words, one wants a coach-horse, and other wants a good hackney, which some would consider the better horse of the two.

Most of the doctors are horsed by the jobmaster. Some of the Harley Street and Cavendish Square men have half-a-dozen horses on hire, which means a nice little addition to their expenses. The horses are usually foraged by the jobmaster, and every fortnight the feed is delivered in sacks at the stable; but the shoeing is done by a local farrier, though at the jobmaster's expense.

There is no doubt that the typical doctor's horse, the horse of the hard-working general practitioner, has a trying life. Like the maid-of-all-work, his work is never done; and he must be exceptionally sound and robust to stand the wear and tear of day and night, particularly on what we may call the outer edge of London. He may not look so well as the animal driven by the country medico, who generally takes a pride in his horseflesh, but he costs quite as much and does not last as long. Six years' work is as much as can be expected of him, and the expectation is frequently unfulfilled, for as a rule he has little time to bo comfortable either in the stable or the street, although many a one-horse doctor walks his round on Sunday, to give his weary steed a rest. Of late years influenza has been exceptionally hard on the doctor's horse; it has hit him in two ways: as an ailment from which he suffers, and as a cause of much extra work. No wonder that the doctor jobs, and avails himself of an inexhaustible supply of horse power, in which the risk is spread over thousands instead of being concentrated on his one poor pill-box bay.

The daily round of the doctor's horse must be as monotonous as that of the milkman's. As a contrast we have the festive outings of that holiday animal, the wedding grey. As we have before noticed, the grey horse is not appreciated by the cabman, nor is he much loved by the omnibus owner or the carrier, but the livery stableman cannot do without him. For a wedding he is indispensable, though in a crush of weddings chestnuts have to take his place, just as in a crush of funerals the 'black masters' have to call on their brethren for the loan of darkish bays and browns.

Tilling averages half-a-dozen weddings a day all the year round, Sundays excepted, for Sunday is not a favourite marriage day among the folks who patronise the jobmaster. To horse these weddings takes about forty horses, most of which do nothing else; but taking London round, the wedding horse is a superior kind of 'bus horse out for a holiday, which he owes not to his merits and points, but to his colour; and it has been observed that the melancholy air with which he eyes the bride and bridegroom is due not so much to his forebodings as to their future, but to his veiling his joy at having such a light day's work.

All the large horse-owners have infirmaries to which the sick and injured are sent, and most of them have a farm for the convalescent. Tilling's infirmary is a special yard about a quarter of a mile from headquarters, where there are over sixty loose boxes and stalls for the patients under treatment. We have already seen how curiously alike to man the horse is in his ailments. This is all the more noticeable at this infirmary from the fact of a slate appearing on each door, on which is written the patient's name, his complaint, and the treatment ordered; it only wants a blue paper by the side of it, to be sent to the dispenser for the medicine, to make the resemblance to a hospital complete.

The horses that die in a livery stable are few, but those cleared out every year amount to about 12 per cent. This gives an average of eight and a half years' work, but it is spread over so many kinds of horses as to be hardly worth consideration.

Published on August 15, 2011 23:48

August 13, 2011

The Charlotte Gunning Portrait at Chawton House by Guest Blogger Hester Davenport

[image error]

The Portrait of Charlotte Gunning (1759-94)copyright Chawton House Library

On 15 May 1784 it was the turn of Charlotte Margaret Gunning, Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte, to have use of the Royal Coach. Her friend Mary Hamilton called at St James's Palace, and went with Charlotte to 'Romney's, the Painter's' where Miss Gunning was 'to sit for her picture'. That half-length portrait now hangs in Chawton House Great Hall.

Mary Hamilton had also been employed in the royal household, to help with the education of the young princesses; she found her duties arduous, thankfully withdrawing from court after five years. Perhaps the two young women talked over the difficulties of royal service, which included their reputations as 'learned ladies'. Both had had 'masculine' educations in the classical languages: according to Fanny Burney Miss Gunning was derogatively nicknamed 'Lady Charlotte Hebrew' for her learning.

Charlotte was the daughter of Sir Robert Gunning (1731-1816), a diplomat who was so successful in conducting the King's business with the Empress of Russia that in 1773 he was made Knight of the Bath. His daughter's appointment as Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte in 1779 was no doubt a further sign of royal favour. He had two other children, his son George who would inherit the baronetcy, and another daughter Barbara. His wife had died when Charlotte was eleven-years-old, but in the 1780s he ordered portraits of himself and his three children from the society portraitist, George Romney (1734-1802).

The painting of the 25-year-old Charlotte is interesting in its apparent contradictions. The colours are muted, with the head veiled in white and the black dress severely plain, yet it is very low-cut, and the sitter looks out self-assured and even challenging. A warm glow in the sky behind suggests there is feeling and passion beneath that cool exterior. Charlotte's hair is dressed high on her head and fashionably powdered. A hat might have been expected, but scarves, called 'fascinators', sometimes replaced large hats, especially for evening wear.

There were six Maids of Honour, paid £300 a year, with duties that must have been stultifyingly dull, standing in attendance at the Queen's 'Drawing rooms' and other court functions (though periods of duty were rotated). Charlotte kept her position for nearly twelve years before managing to escape. It was not easy to withdraw from royal service, as both Mary Hamilton and Fanny Burney discovered, and reaching her thirtieth birthday in 1789 Charlotte must have feared a dreary life of spinsterhood. But on 6 January 1790 she achieved an honourable discharge when she married a widower, Colonel the Honourable Stephen Digby, the Queen's Vice Chamberlain. Another of Charlotte's friends, Mary Noel, wrote in a letter of her surprise that Sir Robert gave his consent 'as it must be a very bad match for her if he has four children', though she also recorded Charlotte saying that she 'can't live without his friendship and could not keep that without marrying him'.

For Fanny Burney the news of the forthcoming wedding was a shock: she believed that Digby had been paying her marked attention for two years and that she should have received the proposal. Her sense of betrayal was huge and she gave vent to her feelings in page after page of her journal. She never blamed Charlotte but no doubt got sly pleasure from noting the King shaking his head over 'Poor Digby' (because his bride was a learned lady) or recording the strange details of the wedding: that it was performed by Dr Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, in the Drawing-room of Sir Robert's house in Northampton, with the guests sitting round on sofas and ladies' workboxes not cleared away. The new Mrs Digby paid a visit to Miss Burney, 'quite brilliant in smiles and spirits' and Fanny did her the justice of saying that she believed that Miss Gunning had 'long cherished a passionate regard' for Colonel Digby.

Two children, Henry Robert and Isabella Margaret, were born in quick succession, but the marriage was not to be long-lasting. In June 1794 Charlotte Digby died (possibly in childbirth - the brief obituary notice in the Genteman's Magazine gives no cause of death). She was buried in the vault of Thames Ditton church where Digby's first wife lay: he would join his two 'dear wives' there in 1800.

Charlotte Gunning wrote no books, has found no place in history. But there could surely be no more suitable place for her portrait than Chawton Women's Library, in the society of so many other 'learned ladies'.

Permission to reprint this article, which first ran in The Female Spectator, was kindly granted by that publication and Chawton House Library. [image error]

The Portrait of Charlotte Gunning (1759-94)copyright Chawton House Library

On 15 May 1784 it was the turn of Charlotte Margaret Gunning, Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte, to have use of the Royal Coach. Her friend Mary Hamilton called at St James's Palace, and went with Charlotte to 'Romney's, the Painter's' where Miss Gunning was 'to sit for her picture'. That half-length portrait now hangs in Chawton House Great Hall.

Mary Hamilton had also been employed in the royal household, to help with the education of the young princesses; she found her duties arduous, thankfully withdrawing from court after five years. Perhaps the two young women talked over the difficulties of royal service, which included their reputations as 'learned ladies'. Both had had 'masculine' educations in the classical languages: according to Fanny Burney Miss Gunning was derogatively nicknamed 'Lady Charlotte Hebrew' for her learning.

Charlotte was the daughter of Sir Robert Gunning (1731-1816), a diplomat who was so successful in conducting the King's business with the Empress of Russia that in 1773 he was made Knight of the Bath. His daughter's appointment as Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte in 1779 was no doubt a further sign of royal favour. He had two other children, his son George who would inherit the baronetcy, and another daughter Barbara. His wife had died when Charlotte was eleven-years-old, but in the 1780s he ordered portraits of himself and his three children from the society portraitist, George Romney (1734-1802).

The painting of the 25-year-old Charlotte is interesting in its apparent contradictions. The colours are muted, with the head veiled in white and the black dress severely plain, yet it is very low-cut, and the sitter looks out self-assured and even challenging. A warm glow in the sky behind suggests there is feeling and passion beneath that cool exterior. Charlotte's hair is dressed high on her head and fashionably powdered. A hat might have been expected, but scarves, called 'fascinators', sometimes replaced large hats, especially for evening wear.

There were six Maids of Honour, paid £300 a year, with duties that must have been stultifyingly dull, standing in attendance at the Queen's 'Drawing rooms' and other court functions (though periods of duty were rotated). Charlotte kept her position for nearly twelve years before managing to escape. It was not easy to withdraw from royal service, as both Mary Hamilton and Fanny Burney discovered, and reaching her thirtieth birthday in 1789 Charlotte must have feared a dreary life of spinsterhood. But on 6 January 1790 she achieved an honourable discharge when she married a widower, Colonel the Honourable Stephen Digby, the Queen's Vice Chamberlain. Another of Charlotte's friends, Mary Noel, wrote in a letter of her surprise that Sir Robert gave his consent 'as it must be a very bad match for her if he has four children', though she also recorded Charlotte saying that she 'can't live without his friendship and could not keep that without marrying him'.

For Fanny Burney the news of the forthcoming wedding was a shock: she believed that Digby had been paying her marked attention for two years and that she should have received the proposal. Her sense of betrayal was huge and she gave vent to her feelings in page after page of her journal. She never blamed Charlotte but no doubt got sly pleasure from noting the King shaking his head over 'Poor Digby' (because his bride was a learned lady) or recording the strange details of the wedding: that it was performed by Dr Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, in the Drawing-room of Sir Robert's house in Northampton, with the guests sitting round on sofas and ladies' workboxes not cleared away. The new Mrs Digby paid a visit to Miss Burney, 'quite brilliant in smiles and spirits' and Fanny did her the justice of saying that she believed that Miss Gunning had 'long cherished a passionate regard' for Colonel Digby.

Two children, Henry Robert and Isabella Margaret, were born in quick succession, but the marriage was not to be long-lasting. In June 1794 Charlotte Digby died (possibly in childbirth - the brief obituary notice in the Genteman's Magazine gives no cause of death). She was buried in the vault of Thames Ditton church where Digby's first wife lay: he would join his two 'dear wives' there in 1800.

Charlotte Gunning wrote no books, has found no place in history. But there could surely be no more suitable place for her portrait than Chawton Women's Library, in the society of so many other 'learned ladies'.

Permission to reprint this article, which first ran in The Female Spectator, was kindly granted by that publication and Chawton House Library. [image error]

Published on August 13, 2011 23:44

The Charlotte Gunning Portrait at Chawton House

[image error]

The Portrait of Charlotte Gunning (1759-94)copyright Chawton House Library

On 15 May 1784 it was the turn of Charlotte Margaret Gunning, Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte, to have use of the Royal Coach. Her friend Mary Hamilton called at St James's Palace, and went with Charlotte to 'Romney's, the Painter's' where Miss Gunning was 'to sit for her picture'. That half-length portrait now hangs in Chawton House Great Hall.

Mary Hamilton had also been employed in the royal household, to help with the education of the young princesses; she found her duties arduous, thankfully withdrawing from court after five years. Perhaps the two young women talked over the difficulties of royal service, which included their reputations as 'learned ladies'. Both had had 'masculine' educations in the classical languages: according to Fanny Burney Miss Gunning was derogatively nicknamed 'Lady Charlotte Hebrew' for her learning.

Charlotte was the daughter of Sir Robert Gunning (1731-1816), a diplomat who was so successful in conducting the King's business with the Empress of Russia that in 1773 he was made Knight of the Bath. His daughter's appointment as Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte in 1779 was no doubt a further sign of royal favour. He had two other children, his son George who would inherit the baronetcy, and another daughter Barbara. His wife had died when Charlotte was eleven-years-old, but in the 1780s he ordered portraits of himself and his three children from the society portraitist, George Romney (1734-1802).

The painting of the 25-year-old Charlotte is interesting in its apparent contradictions. The colours are muted, with the head veiled in white and the black dress severely plain, yet it is very low-cut, and the sitter looks out self-assured and even challenging. A warm glow in the sky behind suggests there is feeling and passion beneath that cool exterior. Charlotte's hair is dressed high on her head and fashionably powdered. A hat might have been expected, but scarves, called 'fascinators', sometimes replaced large hats, especially for evening wear.

There were six Maids of Honour, paid £300 a year, with duties that must have been stultifyingly dull, standing in attendance at the Queen's 'Drawing rooms' and other court functions (though periods of duty were rotated). Charlotte kept her position for nearly twelve years before managing to escape. It was not easy to withdraw from royal service, as both Mary Hamilton and Fanny Burney discovered, and reaching her thirtieth birthday in 1789 Charlotte must have feared a dreary life of spinsterhood. But on 6 January 1790 she achieved an honourable discharge when she married a widower, Colonel the Honourable Stephen Digby, the Queen's Vice Chamberlain. Another of Charlotte's friends, Mary Noel, wrote in a letter of her surprise that Sir Robert gave his consent 'as it must be a very bad match for her if he has four children', though she also recorded Charlotte saying that she 'can't live without his friendship and could not keep that without marrying him'.

For Fanny Burney the news of the forthcoming wedding was a shock: she believed that Digby had been paying her marked attention for two years and that she should have received the proposal. Her sense of betrayal was huge and she gave vent to her feelings in page after page of her journal. She never blamed Charlotte but no doubt got sly pleasure from noting the King shaking his head over 'Poor Digby' (because his bride was a learned lady) or recording the strange details of the wedding: that it was performed by Dr Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, in the Drawing-room of Sir Robert's house in Northampton, with the guests sitting round on sofas and ladies' workboxes not cleared away. The new Mrs Digby paid a visit to Miss Burney, 'quite brilliant in smiles and spirits' and Fanny did her the justice of saying that she believed that Miss Gunning had 'long cherished a passionate regard' for Colonel Digby.

Two children, Henry Robert and Isabella Margaret, were born in quick succession, but the marriage was not to be long-lasting. In June 1794 Charlotte Digby died (possibly in childbirth - the brief obituary notice in the Genteman's Magazine gives no cause of death). She was buried in the vault of Thames Ditton church where Digby's first wife lay: he would join his two 'dear wives' there in 1800.

Charlotte Gunning wrote no books, has found no place in history. But there could surely be no more suitable place for her portrait than Chawton Women's Library, in the society of so many other 'learned ladies'.

Permission to reprint this article, which first ran in The Female Spectator, was kindly granted by that publication and Chawton House Library. [image error]

The Portrait of Charlotte Gunning (1759-94)copyright Chawton House Library

On 15 May 1784 it was the turn of Charlotte Margaret Gunning, Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte, to have use of the Royal Coach. Her friend Mary Hamilton called at St James's Palace, and went with Charlotte to 'Romney's, the Painter's' where Miss Gunning was 'to sit for her picture'. That half-length portrait now hangs in Chawton House Great Hall.

Mary Hamilton had also been employed in the royal household, to help with the education of the young princesses; she found her duties arduous, thankfully withdrawing from court after five years. Perhaps the two young women talked over the difficulties of royal service, which included their reputations as 'learned ladies'. Both had had 'masculine' educations in the classical languages: according to Fanny Burney Miss Gunning was derogatively nicknamed 'Lady Charlotte Hebrew' for her learning.

Charlotte was the daughter of Sir Robert Gunning (1731-1816), a diplomat who was so successful in conducting the King's business with the Empress of Russia that in 1773 he was made Knight of the Bath. His daughter's appointment as Maid of Honour to Queen Charlotte in 1779 was no doubt a further sign of royal favour. He had two other children, his son George who would inherit the baronetcy, and another daughter Barbara. His wife had died when Charlotte was eleven-years-old, but in the 1780s he ordered portraits of himself and his three children from the society portraitist, George Romney (1734-1802).

The painting of the 25-year-old Charlotte is interesting in its apparent contradictions. The colours are muted, with the head veiled in white and the black dress severely plain, yet it is very low-cut, and the sitter looks out self-assured and even challenging. A warm glow in the sky behind suggests there is feeling and passion beneath that cool exterior. Charlotte's hair is dressed high on her head and fashionably powdered. A hat might have been expected, but scarves, called 'fascinators', sometimes replaced large hats, especially for evening wear.

There were six Maids of Honour, paid £300 a year, with duties that must have been stultifyingly dull, standing in attendance at the Queen's 'Drawing rooms' and other court functions (though periods of duty were rotated). Charlotte kept her position for nearly twelve years before managing to escape. It was not easy to withdraw from royal service, as both Mary Hamilton and Fanny Burney discovered, and reaching her thirtieth birthday in 1789 Charlotte must have feared a dreary life of spinsterhood. But on 6 January 1790 she achieved an honourable discharge when she married a widower, Colonel the Honourable Stephen Digby, the Queen's Vice Chamberlain. Another of Charlotte's friends, Mary Noel, wrote in a letter of her surprise that Sir Robert gave his consent 'as it must be a very bad match for her if he has four children', though she also recorded Charlotte saying that she 'can't live without his friendship and could not keep that without marrying him'.

For Fanny Burney the news of the forthcoming wedding was a shock: she believed that Digby had been paying her marked attention for two years and that she should have received the proposal. Her sense of betrayal was huge and she gave vent to her feelings in page after page of her journal. She never blamed Charlotte but no doubt got sly pleasure from noting the King shaking his head over 'Poor Digby' (because his bride was a learned lady) or recording the strange details of the wedding: that it was performed by Dr Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, in the Drawing-room of Sir Robert's house in Northampton, with the guests sitting round on sofas and ladies' workboxes not cleared away. The new Mrs Digby paid a visit to Miss Burney, 'quite brilliant in smiles and spirits' and Fanny did her the justice of saying that she believed that Miss Gunning had 'long cherished a passionate regard' for Colonel Digby.

Two children, Henry Robert and Isabella Margaret, were born in quick succession, but the marriage was not to be long-lasting. In June 1794 Charlotte Digby died (possibly in childbirth - the brief obituary notice in the Genteman's Magazine gives no cause of death). She was buried in the vault of Thames Ditton church where Digby's first wife lay: he would join his two 'dear wives' there in 1800.

Charlotte Gunning wrote no books, has found no place in history. But there could surely be no more suitable place for her portrait than Chawton Women's Library, in the society of so many other 'learned ladies'.

Permission to reprint this article, which first ran in The Female Spectator, was kindly granted by that publication and Chawton House Library. [image error]

Published on August 13, 2011 23:44

August 12, 2011

Earthquake! (Again)

From the Letters of Frances, Lady Shelley

August 12. (Devon 1852) — "We felt a tremendous earthquake shock at Beer Ferrers at 7:30 this morning. It was not felt at Plymouth, but, so far as we can ascertain, it was first felt at Beer Town, where all the crockery ware on the shelves rattled for some seconds. We heard a great noise, like the blowing up of a powder magazine, which we thought must have occurred at Plymouth. The house rocked to its foundations. I happened to be writing at the time, and the pen was dashed out of my hand. At Beer Alston, due north from here, the shock was greater. Tiles were thrown from the roof, people rushed into the street, and in the new mine close to the Tamar, those who were working in the upper gallery rushed below, believing that the earth had fallen in upon the men working there. At Tavistock a chemist told me that all his bottles rattled and shook so much that he expected them to fall to the floor. On the Moor many of the great stones were detached from the Tor, and at Two Bridges the landlord told us that while he was in his stable the noise and shaking was so great that he ran out thinking that the building would fall about his ears. On the first floor of his house the children screamed, and his wife expected the floor to give way. A wall had been thrown down at Widdicombe, on the Exeter road. We have traced the shock in a direction from east to west, increasing in intensity as it proceeded.

St. Pancras Church, Widecombe

"The last recorded convulsion of this kind was in October 1752, just a hundred years ago. During the evening service in Widdicombe church, a ball of fire burst through one of the windows, and passed down the nave. Large stones, which were detached from the tower of the church, broke through the roof. The clergyman, the Rev. Mr. Lynn, and his clerk remained in their places, and a huge beam from the roof actually fell between them. The clergyman continued to pray aloud, in the presence only of the dead and the wounded. Four persons were killed, and sixty-two persons seriously injured. The most harrowing tales respecting this shock are still told by the peasantry of Dartmoor. A hundred years ago the shock was heralded by a violent storm of thunder and lightning. On the present occasion there was no storm. The sky was overcast, the air was heavily charged, and had been so for some days."

August 12. (Devon 1852) — "We felt a tremendous earthquake shock at Beer Ferrers at 7:30 this morning. It was not felt at Plymouth, but, so far as we can ascertain, it was first felt at Beer Town, where all the crockery ware on the shelves rattled for some seconds. We heard a great noise, like the blowing up of a powder magazine, which we thought must have occurred at Plymouth. The house rocked to its foundations. I happened to be writing at the time, and the pen was dashed out of my hand. At Beer Alston, due north from here, the shock was greater. Tiles were thrown from the roof, people rushed into the street, and in the new mine close to the Tamar, those who were working in the upper gallery rushed below, believing that the earth had fallen in upon the men working there. At Tavistock a chemist told me that all his bottles rattled and shook so much that he expected them to fall to the floor. On the Moor many of the great stones were detached from the Tor, and at Two Bridges the landlord told us that while he was in his stable the noise and shaking was so great that he ran out thinking that the building would fall about his ears. On the first floor of his house the children screamed, and his wife expected the floor to give way. A wall had been thrown down at Widdicombe, on the Exeter road. We have traced the shock in a direction from east to west, increasing in intensity as it proceeded.

St. Pancras Church, Widecombe

"The last recorded convulsion of this kind was in October 1752, just a hundred years ago. During the evening service in Widdicombe church, a ball of fire burst through one of the windows, and passed down the nave. Large stones, which were detached from the tower of the church, broke through the roof. The clergyman, the Rev. Mr. Lynn, and his clerk remained in their places, and a huge beam from the roof actually fell between them. The clergyman continued to pray aloud, in the presence only of the dead and the wounded. Four persons were killed, and sixty-two persons seriously injured. The most harrowing tales respecting this shock are still told by the peasantry of Dartmoor. A hundred years ago the shock was heralded by a violent storm of thunder and lightning. On the present occasion there was no storm. The sky was overcast, the air was heavily charged, and had been so for some days."

Published on August 12, 2011 01:14

August 11, 2011

Travels With Victoria: Marlborough House

Saturday, June 11, 2011, was not only the Trooping of the Colour (see my post of 7/30/11). It was the first day of the Open Squares weekend. Being an unabashed Nosey Parker, I love this time when many of the private squares and parks in London are opened to the public.

Garden at Carlton House Terrace

While the Queen was reviewing her troops on the parade ground at Horse Guards, I wandered to a few of the gardens in the vicinity of St. James.

[image error]

Marlborough House, St. James

You can take an excellent virtual tour of the interior and exterior of the house here. Marlborough House is now the home of the Commonwealth Secretariat and the Commonwealth Foundation.

In learning more about Marlborough House, I found it was associated with a large number of remarkable people, particularly women. The house was built on land leased from the crown adjoining St. James Palace for Sarah Churchill, 1st Duchess of Marlborough, who was a close friend of and adviser to Queen Anne.

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough (1660-1744) National Portrait Gallery

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough (1660-1744) National Portrait Gallery

Sarah chose as architect Sir Christopher Wren. She disliked Sir John Vanbrugh who was building Blenheim, the magnificent baroque country house in Oxfordshire which was to be a gift of a grateful nation to the 1st Duke of Marlborough for his victory in the Battle of Blenheim in 1704.

The Original Marlborough House

The Original Marlborough House

Sarah wanted a plain and convenient house, without florid embellishments; in her own words, "...unlike anything at Blenheim." She laid the foundation cornerstone in 1709, but she quarreled with and later dismissed Wren. The feisty duchess took over the supervision of Marlborough House's completion. Like her disputes with the Blenheim builders, the economical and thrifty Sarah refused to give in to excessive costs and overcharging.

Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723)

Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723)

Wren's original design was dramatically altered in 1770 when a third floor and additional wings were added.

The Marlborough family occupied the house until 1817 when the property reverted to the Crown. Marlborough House was being prepared to be the London home of Princess Charlotte and her husband Prince Leopold with their expected child when the Princess died in childbirth in November, 1817, putting the entire country into mourning.

The Marlborough family occupied the house until 1817 when the property reverted to the Crown. Marlborough House was being prepared to be the London home of Princess Charlotte and her husband Prince Leopold with their expected child when the Princess died in childbirth in November, 1817, putting the entire country into mourning.

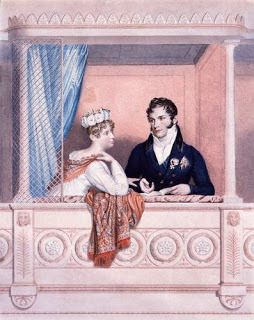

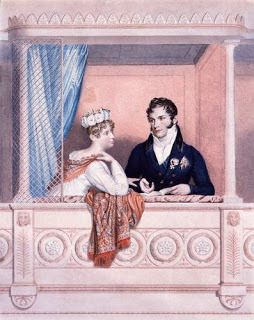

Charlotte and Leopold, c. 1816

Leopold did occupy Marlborough House and lived there until he became King of Belgium in 1831. He was not only the widower of Princess Charlotte; he was the brother of the Duchess of Kent and uncle to Princess Victoria. Marlborough House was next presented to Queen Adelaide, consort of William IV, for her use.

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, Queen of England (1792-1849)

Adelaide, the first dowager queen for almost 150 years, did not spend a great deal of time at Marlborough House. She was viewed with suspicion by the Duchess of Kent and other advisors to the young Queen Victoria, and thus spent more time in the country wandering from one rented house to another.

Years later, a collection of artifacts from the Great Exposition of 1851 was displayed to the public in Marlborough House, making it a museum of arts and science. It's success led to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert deciding to build permanent displays on a grand scale, which became the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington.

After a period of time when it was used as a national art school, the building was remodeled as a home for the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII (1841-1910), and his wife Alexandra of Denmark. Further additions were made before the couple moved in. Their active social life led to the fame of the Marlborough House Set, a circle of fashionable aristocrats as well as a few who were not very aristocratic at all. But no doubt amusing!

Anita Leslie's 1973 book about this Eawardian group makes fascinating reading. George V was born here in 1903. After Queen Victoria died, Bertie (having lived for decades as Prince of Wales) reigned only only nine years as Edward VII. Another dowager queen, Alexandra moved back to Marlborough House, where she lived until her death in 1925.

Queen Alexandra

To return to my visit to the Marlborough House Garden, I enjoyed a cup of tea and sat on a damp bench -- the weather was cool and occasionally it tried to rain, but I believe that is not allowed on the day of Trooping the Colour, so it always blew away in a short time.

The Garden brochure says, "The garden has been largely maintained in its original formal 18th-century layout, with a number of large, plain expanses of lawn, intersected by gravel pathways." Flowers and hedges were restricted to the boundaries, but at the eastern end, there is a shrubbery with a woodland path where I found the pet cemetery.

A row of little headstones marks the final resting point for some of Alexandra's most beloved pets.

A row of little headstones marks the final resting point for some of Alexandra's most beloved pets.

On several of the stones there were pictures of the little dogs, which looked like King Charles spaniels, with their mistress.

On several of the stones there were pictures of the little dogs, which looked like King Charles spaniels, with their mistress.

As I walked around the garden, I realized that the bands I heard were right outside the wall as the troops returned to Buckingham Palace from Trooping the Colour. A little cluster of us peered over the wall and watched the parade.

As I walked around the garden, I realized that the bands I heard were right outside the wall as the troops returned to Buckingham Palace from Trooping the Colour. A little cluster of us peered over the wall and watched the parade.

The Queen and Prince Philip on their way back to the Palace for the flyover by the Royal Air Force.

The Queen and Prince Philip on their way back to the Palace for the flyover by the Royal Air Force.

A final view of Marlborough House.

A final view of Marlborough House.

Memorial to Queen Alexandra just outside Marlborough House where she lived much of her life. It was designed by Sir Alfred Gilbert and dedicated in 1932 by George V, Queen Alexandra's son.

Memorial to Queen Alexandra just outside Marlborough House where she lived much of her life. It was designed by Sir Alfred Gilbert and dedicated in 1932 by George V, Queen Alexandra's son.

Travels with Victoria has only a few more stops to make; watch for them after a short break.[image error]

Garden at Carlton House Terrace

While the Queen was reviewing her troops on the parade ground at Horse Guards, I wandered to a few of the gardens in the vicinity of St. James.

[image error]

Marlborough House, St. James

You can take an excellent virtual tour of the interior and exterior of the house here. Marlborough House is now the home of the Commonwealth Secretariat and the Commonwealth Foundation.

In learning more about Marlborough House, I found it was associated with a large number of remarkable people, particularly women. The house was built on land leased from the crown adjoining St. James Palace for Sarah Churchill, 1st Duchess of Marlborough, who was a close friend of and adviser to Queen Anne.

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough (1660-1744) National Portrait Gallery

Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough (1660-1744) National Portrait Gallery Sarah chose as architect Sir Christopher Wren. She disliked Sir John Vanbrugh who was building Blenheim, the magnificent baroque country house in Oxfordshire which was to be a gift of a grateful nation to the 1st Duke of Marlborough for his victory in the Battle of Blenheim in 1704.

The Original Marlborough House

The Original Marlborough HouseSarah wanted a plain and convenient house, without florid embellishments; in her own words, "...unlike anything at Blenheim." She laid the foundation cornerstone in 1709, but she quarreled with and later dismissed Wren. The feisty duchess took over the supervision of Marlborough House's completion. Like her disputes with the Blenheim builders, the economical and thrifty Sarah refused to give in to excessive costs and overcharging.

Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723)

Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723) Wren's original design was dramatically altered in 1770 when a third floor and additional wings were added.

The Marlborough family occupied the house until 1817 when the property reverted to the Crown. Marlborough House was being prepared to be the London home of Princess Charlotte and her husband Prince Leopold with their expected child when the Princess died in childbirth in November, 1817, putting the entire country into mourning.

The Marlborough family occupied the house until 1817 when the property reverted to the Crown. Marlborough House was being prepared to be the London home of Princess Charlotte and her husband Prince Leopold with their expected child when the Princess died in childbirth in November, 1817, putting the entire country into mourning.

Charlotte and Leopold, c. 1816

Leopold did occupy Marlborough House and lived there until he became King of Belgium in 1831. He was not only the widower of Princess Charlotte; he was the brother of the Duchess of Kent and uncle to Princess Victoria. Marlborough House was next presented to Queen Adelaide, consort of William IV, for her use.

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, Queen of England (1792-1849)

Adelaide, the first dowager queen for almost 150 years, did not spend a great deal of time at Marlborough House. She was viewed with suspicion by the Duchess of Kent and other advisors to the young Queen Victoria, and thus spent more time in the country wandering from one rented house to another.

Years later, a collection of artifacts from the Great Exposition of 1851 was displayed to the public in Marlborough House, making it a museum of arts and science. It's success led to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert deciding to build permanent displays on a grand scale, which became the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington.

After a period of time when it was used as a national art school, the building was remodeled as a home for the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII (1841-1910), and his wife Alexandra of Denmark. Further additions were made before the couple moved in. Their active social life led to the fame of the Marlborough House Set, a circle of fashionable aristocrats as well as a few who were not very aristocratic at all. But no doubt amusing!

Anita Leslie's 1973 book about this Eawardian group makes fascinating reading. George V was born here in 1903. After Queen Victoria died, Bertie (having lived for decades as Prince of Wales) reigned only only nine years as Edward VII. Another dowager queen, Alexandra moved back to Marlborough House, where she lived until her death in 1925.

Queen Alexandra

To return to my visit to the Marlborough House Garden, I enjoyed a cup of tea and sat on a damp bench -- the weather was cool and occasionally it tried to rain, but I believe that is not allowed on the day of Trooping the Colour, so it always blew away in a short time.

The Garden brochure says, "The garden has been largely maintained in its original formal 18th-century layout, with a number of large, plain expanses of lawn, intersected by gravel pathways." Flowers and hedges were restricted to the boundaries, but at the eastern end, there is a shrubbery with a woodland path where I found the pet cemetery.

A row of little headstones marks the final resting point for some of Alexandra's most beloved pets.

A row of little headstones marks the final resting point for some of Alexandra's most beloved pets. On several of the stones there were pictures of the little dogs, which looked like King Charles spaniels, with their mistress.

On several of the stones there were pictures of the little dogs, which looked like King Charles spaniels, with their mistress.  As I walked around the garden, I realized that the bands I heard were right outside the wall as the troops returned to Buckingham Palace from Trooping the Colour. A little cluster of us peered over the wall and watched the parade.

As I walked around the garden, I realized that the bands I heard were right outside the wall as the troops returned to Buckingham Palace from Trooping the Colour. A little cluster of us peered over the wall and watched the parade. The Queen and Prince Philip on their way back to the Palace for the flyover by the Royal Air Force.

The Queen and Prince Philip on their way back to the Palace for the flyover by the Royal Air Force. A final view of Marlborough House.

A final view of Marlborough House. Memorial to Queen Alexandra just outside Marlborough House where she lived much of her life. It was designed by Sir Alfred Gilbert and dedicated in 1932 by George V, Queen Alexandra's son.

Memorial to Queen Alexandra just outside Marlborough House where she lived much of her life. It was designed by Sir Alfred Gilbert and dedicated in 1932 by George V, Queen Alexandra's son. Travels with Victoria has only a few more stops to make; watch for them after a short break.[image error]

Published on August 11, 2011 02:00

August 9, 2011

Snorkeling the Atlantis Ruins

During our recent trip to the Atlantis Resort in Nassau, Brooke and I spent some time snorkeling the underwater ruins.

[image error]

The two million gallon tank holds sharks, manta rays, eels, grouper and a variety of other sea life and can be seen through windows in the underwater walkway that meanders through the resort.

[image error]

[image error]

Man-made ruins recreate the Lost City of Atlantis.

[image error]

We donned our snorkel kit and dove in - along with several others in our group, including a teenaged girl who screamed out loud whenever she saw anything that moved. Believe me, there was alot of moving sea life. Thus, a lot of screaming. Where were the sharks when we needed them?

[image error]

It was pretty incredible to be swimming whilst surrounded by an array of sea life.

[image error]

All was going along swimmingly (har, har) until I turned around and came face to face with a Manta ray that was literally about ten feet away. What to do? Do I swim up - or down? Who has the right of way? What is the proper underwater etiquette for situations like this?

[image error]

Thankfully, the Ray solved the problem by diving beneath me and swimming away. He could have at least introduced himself . . . .

[image error]

The rest of the dive was beautiful, if uneventful.

[image error]

I swam by a resting Giant Grouper . . .

[image error]

And took time out to wave to those looking into the tank through the windows.

[image error] [image error]

This eel had the good grace to stay in his hidey-hole and not scare the life out of me.

[image error]

[image error]

So ended our snorkeling adventure. One of the women in our group approached me as I dried off and said, "Oh. My. God. I couldn't believe how close that Ray got to you!" I didn't think anyone else had noticed my close call, but apparently they had. Actually, the encounter with the Ray was nothing as compared to having to listen to that girl scream at the top of her lungs for an hour. My ears are still ringing. All of this begs the question, "If you're that scared of fish, why go snorkeling?" [image error]

[image error]

The two million gallon tank holds sharks, manta rays, eels, grouper and a variety of other sea life and can be seen through windows in the underwater walkway that meanders through the resort.

[image error]

[image error]

Man-made ruins recreate the Lost City of Atlantis.

[image error]

We donned our snorkel kit and dove in - along with several others in our group, including a teenaged girl who screamed out loud whenever she saw anything that moved. Believe me, there was alot of moving sea life. Thus, a lot of screaming. Where were the sharks when we needed them?

[image error]

It was pretty incredible to be swimming whilst surrounded by an array of sea life.

[image error]

All was going along swimmingly (har, har) until I turned around and came face to face with a Manta ray that was literally about ten feet away. What to do? Do I swim up - or down? Who has the right of way? What is the proper underwater etiquette for situations like this?

[image error]

Thankfully, the Ray solved the problem by diving beneath me and swimming away. He could have at least introduced himself . . . .

[image error]

The rest of the dive was beautiful, if uneventful.

[image error]

I swam by a resting Giant Grouper . . .

[image error]

And took time out to wave to those looking into the tank through the windows.

[image error] [image error]

This eel had the good grace to stay in his hidey-hole and not scare the life out of me.

[image error]

[image error]

So ended our snorkeling adventure. One of the women in our group approached me as I dried off and said, "Oh. My. God. I couldn't believe how close that Ray got to you!" I didn't think anyone else had noticed my close call, but apparently they had. Actually, the encounter with the Ray was nothing as compared to having to listen to that girl scream at the top of her lungs for an hour. My ears are still ringing. All of this begs the question, "If you're that scared of fish, why go snorkeling?" [image error]

Published on August 09, 2011 00:30

August 7, 2011

The History of Greys Court by Jo Manning - Part Two

The early 18th century wing of the house has splendid, detailed plasterwork dated from 1760; the kitchen, modernized to the mid-20th century, is spacious and cheerful. One can imagine the last owner, Lady Brunner, whipping up trifle and Yorkshire puds. There is nothing at all pretentious about it.

The house is situated in the western part of the de Greys' medieval courtyard, facing the Great Tower -- built and crenellated so long ago by John de Grey upon his return from war in France. The 12th-century, the 14th, Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean times, sit side by side, an abundant and unique richness for the eye.

[image error]

copyright Peter Goodearl

I like this photo because it shows the 14th century Great Tower, the 16th century (Jacobean) house, and the bits of old stone (the lighter colored ones) from the medieval walls used in the construction of the newer houseIn 1937, Sir Felix and the afore-mentioned Lady Brunner brought Greys Court, creating the many contemporary fine gardens and walks and bringing a very different kind of lifestyle to the Medieval/Jacobean history of Greys Court and its environs. For a very brief period, the property had been held by Lady Evelyn Fleming, mother of the travel writer Peter Fleming and his perhaps more famous brother Ian, author of the James Bond spy novels. Lady Fleming's tenure was marked by "improvements" to the property that were quickly reversed by the new owners, the Brunners, whose taste – thank goodness! -- was quite different. The family that was to make Greys Court its home for over 65 years was not from an ancient and titled background, but rather a newer Victorian-created title…and the theatrical world. Thus began a whole new chapter in the fabulous history of Greys Court.

Elizabeth, Lady Brunner (see her obituary, January 28th, 2003, in The Telegraph was born Dorothea Elizabeth Irving, the daughter of H.B. Irving and Dorothea Baird, both of whom were actors. (Her mother created the parts of Trilby in George du Maurier's play of that name, and Mrs. Darling in Peter Pan .) Her grandfather was the famous actor-manager Sir Henry Irving, whose original family name was Brodribb. It was no surprise when she, too, trod the boards, making her stage debut at the age of 12. Her credits as an adult were to include Titania in A Midsummer Night's Dream , in Trilby , like her mother, and a role in a silent film version of Charlotte Bronte's novel, Shirley .

She married Sir Felix Brunner, a baronet, in 1926 and gave up her acting career. Her husband's family was of Swiss descent; his great-great grandfather, a Protestant minister, had emigrated to Liverpool in 1832. Sir Felix and Lady Brunner had five sons, who grew up at Greys Court. The family donated the property to the National Trust in 1969 and the elder Brunners lived there for the rest of their lives. As I said above, it is homey, not luxurious, and although filled with wonderful theatrical memorabilia (including a cast of Sir Henry Irving's hands) and an extensive library of novels and plays amongst other volumes, one can imagine a young and growing family living there. The bedrooms and bathrooms are rather modest.

A fey touch is a wooden statue in honor of the Brunners' head gardener that is quite amazing to venture upon! There is nothing the least bit stuffy about Greys Court, which is probably why, on the day we went, there were so many young families milling about. And, yes, the Tea Room is lovely, and the giftshop is full of plants, seeds, garden implements and other items for the garden, as befits the nature of Greys Court.

A brief postscript to our visit….

We stopped at Henley-upon-Thames before continuing to Greys Court, where we bought a stuffed toy at Asquith's at 2-4 New Street for my youngest grandchild, 5-year-old Lily. Click here to see this charming shop for yourselves. She chose – amongst hundreds of teddy bears! – a sweet and rather realistic looking hare. Now, note the sign below about Red Kites:

[image error] They are very much in evidence at Greys Court, these handsome once-extinct-in-England birds of prey, circling, in particular, the area above the car park where visitors go to have their picnics. We suddenly noticed that one bird seemed to be swooping lower and lower, its beady eyes on the little hare from Asquith's! Hurriedly, not wanting the hare to become kite food, we stuffed it into the picnic hamper, and not a minute too soon J It would have been rather a sight, and not at all a happy one, for Lily to see her hare picked up for lunch! (It was quite a realistic-looking little hare!)For opening times at Greys Court, et cetera, click here.

The house is situated in the western part of the de Greys' medieval courtyard, facing the Great Tower -- built and crenellated so long ago by John de Grey upon his return from war in France. The 12th-century, the 14th, Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean times, sit side by side, an abundant and unique richness for the eye.

[image error]

copyright Peter Goodearl

I like this photo because it shows the 14th century Great Tower, the 16th century (Jacobean) house, and the bits of old stone (the lighter colored ones) from the medieval walls used in the construction of the newer houseIn 1937, Sir Felix and the afore-mentioned Lady Brunner brought Greys Court, creating the many contemporary fine gardens and walks and bringing a very different kind of lifestyle to the Medieval/Jacobean history of Greys Court and its environs. For a very brief period, the property had been held by Lady Evelyn Fleming, mother of the travel writer Peter Fleming and his perhaps more famous brother Ian, author of the James Bond spy novels. Lady Fleming's tenure was marked by "improvements" to the property that were quickly reversed by the new owners, the Brunners, whose taste – thank goodness! -- was quite different. The family that was to make Greys Court its home for over 65 years was not from an ancient and titled background, but rather a newer Victorian-created title…and the theatrical world. Thus began a whole new chapter in the fabulous history of Greys Court.

Elizabeth, Lady Brunner (see her obituary, January 28th, 2003, in The Telegraph was born Dorothea Elizabeth Irving, the daughter of H.B. Irving and Dorothea Baird, both of whom were actors. (Her mother created the parts of Trilby in George du Maurier's play of that name, and Mrs. Darling in Peter Pan .) Her grandfather was the famous actor-manager Sir Henry Irving, whose original family name was Brodribb. It was no surprise when she, too, trod the boards, making her stage debut at the age of 12. Her credits as an adult were to include Titania in A Midsummer Night's Dream , in Trilby , like her mother, and a role in a silent film version of Charlotte Bronte's novel, Shirley .

She married Sir Felix Brunner, a baronet, in 1926 and gave up her acting career. Her husband's family was of Swiss descent; his great-great grandfather, a Protestant minister, had emigrated to Liverpool in 1832. Sir Felix and Lady Brunner had five sons, who grew up at Greys Court. The family donated the property to the National Trust in 1969 and the elder Brunners lived there for the rest of their lives. As I said above, it is homey, not luxurious, and although filled with wonderful theatrical memorabilia (including a cast of Sir Henry Irving's hands) and an extensive library of novels and plays amongst other volumes, one can imagine a young and growing family living there. The bedrooms and bathrooms are rather modest.

A fey touch is a wooden statue in honor of the Brunners' head gardener that is quite amazing to venture upon! There is nothing the least bit stuffy about Greys Court, which is probably why, on the day we went, there were so many young families milling about. And, yes, the Tea Room is lovely, and the giftshop is full of plants, seeds, garden implements and other items for the garden, as befits the nature of Greys Court.

A brief postscript to our visit….

We stopped at Henley-upon-Thames before continuing to Greys Court, where we bought a stuffed toy at Asquith's at 2-4 New Street for my youngest grandchild, 5-year-old Lily. Click here to see this charming shop for yourselves. She chose – amongst hundreds of teddy bears! – a sweet and rather realistic looking hare. Now, note the sign below about Red Kites:

[image error] They are very much in evidence at Greys Court, these handsome once-extinct-in-England birds of prey, circling, in particular, the area above the car park where visitors go to have their picnics. We suddenly noticed that one bird seemed to be swooping lower and lower, its beady eyes on the little hare from Asquith's! Hurriedly, not wanting the hare to become kite food, we stuffed it into the picnic hamper, and not a minute too soon J It would have been rather a sight, and not at all a happy one, for Lily to see her hare picked up for lunch! (It was quite a realistic-looking little hare!)For opening times at Greys Court, et cetera, click here.

Published on August 07, 2011 00:11

The History of Grey's Court by Jo Manning - Part Two

The early 18th century wing of the house has splendid, detailed plasterwork dated from 1760; the kitchen, modernized to the mid-20th century, is spacious and cheerful. One can imagine the last owner, Lady Brunner, whipping up trifle and Yorkshire puds. There is nothing at all pretentious about it.

The house is situated in the western part of the de Greys' medieval courtyard, facing the Great Tower -- built and crenellated so long ago by John de Grey upon his return from war in France. The 12th-century, the 14th, Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean times, sit side by side, an abundant and unique richness for the eye.

[image error] copyright Peter Goodearl

I like this photo because it shows the 14th century Great Tower, the 16th century (Jacobean) house, and the bits of old stone (the lighter colored ones) from the medieval walls used in the construction of the newer houseIn 1937, Sir Felix and the afore-mentioned Lady Brunner brought Greys Court, creating the many contemporary fine gardens and walks and bringing a very different kind of lifestyle to the Medieval/Jacobean history of Greys Court and its environs. For a very brief period, the property had been held by Lady Evelyn Fleming, mother of the travel writer Peter Fleming and his perhaps more famous brother Ian, author of the James Bond spy novels. Lady Fleming's tenure was marked by "improvements" to the property that were quickly reversed by the new owners, the Brunners, whose taste – thank goodness! -- was quite different. The family that was to make Greys Court its home for over 65 years was not from an ancient and titled background, but rather a newer Victorian-created title…and the theatrical world. Thus began a whole new chapter in the fabulous history of Greys Court.

Elizabeth, Lady Brunner (see her obituary, January 28th, 2003, in The Telegraph was born Dorothea Elizabeth Irving, the daughter of H.B. Irving and Dorothea Baird, both of whom were actors. (Her mother created the parts of Trilby in George du Maurier's play of that name, and Mrs. Darling in Peter Pan .) Her grandfather was the famous actor-manager Sir Henry Irving, whose original family name was Brodribb. It was no surprise when she, too, trod the boards, making her stage debut at the age of 12. Her credits as an adult were to include Titania in A Midsummer Night's Dream , in Trilby , like her mother, and a role in a silent film version of Charlotte Bronte's novel, Shirley .

She married Sir Felix Brunner, a baronet, in 1926 and gave up her acting career. Her husband's family was of Swiss descent; his great-great grandfather, a Protestant minister, had emigrated to Liverpool in 1832. Sir Felix and Lady Brunner had five sons, who grew up at Greys Court. The family donated the property to the National Trust in 1969 and the elder Brunners lived there for the rest of their lives. As I said above, it is homey, not luxurious, and although filled with wonderful theatrical memorabilia (including a cast of Sir Henry Irving's hands) and an extensive library of novels and plays amongst other volumes, one can imagine a young and growing family living there. The bedrooms and bathrooms are rather modest.

A fey touch is a wooden statue in honor of the Brunners' head gardener that is quite amazing to venture upon! There is nothing the least bit stuffy about Greys Court, which is probably why, on the day we went, there were so many young families milling about. And, yes, the Tea Room is lovely, and the giftshop is full of plants, seeds, garden implements and other items for the garden, as befits the nature of Greys Court.

A brief postscript to our visit….

We stopped at Henley-upon-Thames before continuing to Greys Court, where we bought a stuffed toy at Asquith's at 2-4 New Street for my youngest grandchild, 5-year-old Lily. Click here to see this charming shop for yourselves. She chose – amongst hundreds of teddy bears! – a sweet and rather realistic looking hare. Now, note the sign below about Red Kites:

[image error] They are very much in evidence at Greys Court, these handsome once-extinct-in-England birds of prey, circling, in particular, the area above the car park where visitors go to have their picnics. We suddenly noticed that one bird seemed to be swooping lower and lower, its beady eyes on the little hare from Asquith's! Hurriedly, not wanting the hare to become kite food, we stuffed it into the picnic hamper, and not a minute too soon J It would have been rather a sight, and not at all a happy one, for Lily to see her hare picked up for lunch! (It was quite a realistic-looking little hare!)For opening times at Grey's Court, et cetera, click here.

The house is situated in the western part of the de Greys' medieval courtyard, facing the Great Tower -- built and crenellated so long ago by John de Grey upon his return from war in France. The 12th-century, the 14th, Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean times, sit side by side, an abundant and unique richness for the eye.

[image error] copyright Peter Goodearl

I like this photo because it shows the 14th century Great Tower, the 16th century (Jacobean) house, and the bits of old stone (the lighter colored ones) from the medieval walls used in the construction of the newer houseIn 1937, Sir Felix and the afore-mentioned Lady Brunner brought Greys Court, creating the many contemporary fine gardens and walks and bringing a very different kind of lifestyle to the Medieval/Jacobean history of Greys Court and its environs. For a very brief period, the property had been held by Lady Evelyn Fleming, mother of the travel writer Peter Fleming and his perhaps more famous brother Ian, author of the James Bond spy novels. Lady Fleming's tenure was marked by "improvements" to the property that were quickly reversed by the new owners, the Brunners, whose taste – thank goodness! -- was quite different. The family that was to make Greys Court its home for over 65 years was not from an ancient and titled background, but rather a newer Victorian-created title…and the theatrical world. Thus began a whole new chapter in the fabulous history of Greys Court.

Elizabeth, Lady Brunner (see her obituary, January 28th, 2003, in The Telegraph was born Dorothea Elizabeth Irving, the daughter of H.B. Irving and Dorothea Baird, both of whom were actors. (Her mother created the parts of Trilby in George du Maurier's play of that name, and Mrs. Darling in Peter Pan .) Her grandfather was the famous actor-manager Sir Henry Irving, whose original family name was Brodribb. It was no surprise when she, too, trod the boards, making her stage debut at the age of 12. Her credits as an adult were to include Titania in A Midsummer Night's Dream , in Trilby , like her mother, and a role in a silent film version of Charlotte Bronte's novel, Shirley .

She married Sir Felix Brunner, a baronet, in 1926 and gave up her acting career. Her husband's family was of Swiss descent; his great-great grandfather, a Protestant minister, had emigrated to Liverpool in 1832. Sir Felix and Lady Brunner had five sons, who grew up at Greys Court. The family donated the property to the National Trust in 1969 and the elder Brunners lived there for the rest of their lives. As I said above, it is homey, not luxurious, and although filled with wonderful theatrical memorabilia (including a cast of Sir Henry Irving's hands) and an extensive library of novels and plays amongst other volumes, one can imagine a young and growing family living there. The bedrooms and bathrooms are rather modest.

A fey touch is a wooden statue in honor of the Brunners' head gardener that is quite amazing to venture upon! There is nothing the least bit stuffy about Greys Court, which is probably why, on the day we went, there were so many young families milling about. And, yes, the Tea Room is lovely, and the giftshop is full of plants, seeds, garden implements and other items for the garden, as befits the nature of Greys Court.

A brief postscript to our visit….

We stopped at Henley-upon-Thames before continuing to Greys Court, where we bought a stuffed toy at Asquith's at 2-4 New Street for my youngest grandchild, 5-year-old Lily. Click here to see this charming shop for yourselves. She chose – amongst hundreds of teddy bears! – a sweet and rather realistic looking hare. Now, note the sign below about Red Kites:

[image error] They are very much in evidence at Greys Court, these handsome once-extinct-in-England birds of prey, circling, in particular, the area above the car park where visitors go to have their picnics. We suddenly noticed that one bird seemed to be swooping lower and lower, its beady eyes on the little hare from Asquith's! Hurriedly, not wanting the hare to become kite food, we stuffed it into the picnic hamper, and not a minute too soon J It would have been rather a sight, and not at all a happy one, for Lily to see her hare picked up for lunch! (It was quite a realistic-looking little hare!)For opening times at Grey's Court, et cetera, click here.

Published on August 07, 2011 00:11

August 5, 2011

The History of Greys Court by Jo Manning

GREYS COURT, AN UNUSUALLY BEAUTIFUL NATIONAL TRUST SITE NEAR HENLEY-UPON-THAMES

[image error]

On my latest visit to London this past spring, my daughter suggested that we go to Greys Court, a National Trust house she'd been curious about but had never visited. The original buildings on the site dated from before the 12th-century and there was a famous garden; it was in the foothills of the Chilterns, outside of Henley-on-Thames (where I'd never been) and we could explore that town as well. We'd picnic on the extensive grassy grounds overlooking the house and have tea later in the Tea Room located in the Cromwellian Stables.

(Yes, I know, looking at the photo above – that is certainly not a medieval building! – but the rest of the surrounding buildings – erected over at least 600 years -- are decidedly from the early medieval period and these very well evoke for the visitor those days of yore.)

This site is mentioned in the 11th century Domesday Book as Redrefield (Rotherfield). The owners were the de Grey family, barons who fought with their kings at Crecy, Bosworth, in the Scottish wars, and in the Hundred Years War with France. The most famous of the de Greys was John de Grey, a professional soldier who became one of the original Knights of the Garter. After the Battle of Crecy 1346 he was given a license to crenellate Rotherfield, i.e., fortifying it by providing the walls with battlements.