Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 148

May 27, 2011

The Darker Side of London History - Captain Coram and the Foundling Hospital - Part Two

From Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital by John Brownlow (1847)

". . . . the difficulty which presented itself paramount to all others, related to the manner in which so great a number of children was to be reared. In the first year of this indiscriminate admission, the number received was 3,296; in the second year, 4,085; in the third, 4,229; and during less than ten months of the fourth year (after which the system of indiscriminate reception was abolished), 3,324. Thus, in this short period, no less than 14,934 infants were cast on the compassionate protection of the public! It necessarily became a question how the lives of this army of infants could be best preserved; and the Governors, not being able to settle this point among themselves, addressed certain queries to the College of Physicians, which were promptly answered, by recommending a course of treatment consonant to nature and common sense! Children, deprived as these were of their natural aliment, required more than usual watchfulness; and although, on a small scale, the providing a given number of healthy wet-nurses, as substitutes for the mothers of infants, would have been an easy task, yet, when they arrived in numbers so considerable, the Governors found that the object they had in view must necessarily fail from its very magnitude.

"It has been truly said, that the frail tenure by which an infant holds its life, will not allow of a remitted attention even for a few hours: who, therefore, will be surprised, after hearing under what circumstances most of these poor children were left at the Hospital gate, that, instead of being a protection to the living, the institution became, as it were, a charnel-house for the dead! It is a notorious fact, that many of the infants received at the gate, did not live to be carried into the wards of the building; and from the impossibility of procuring a sufficient number of proper nurses, the emaciated and diseased state in which many of these children were brought to the Hospital, and the malconduct of some of those to whose care they were committed (notwithstanding these nurses were under the superintendence of certain ladies—sisters of charity), the deaths amongst them were so frequent, that of the 14,934 received, only 4,400 lived to be apprenticed out, being a mortality of more than seventy per cent."

James II shilling copyright icollector.com

James II shilling copyright icollector.com Charles Knight writes more on this theme in Knight's Cyclopædia of London (1851) -

"Of 14,934 children received under the new system, only 4400 lived to be apprenticed! On the 8th of February, 1760, a resolution was passed in Parliament, declaring "That the indiscriminate admission of all children under a certain age into the Hospital had been attended with many evil consequences, and that it be discontinued." From 1756 to 1771, the years of the Parliamentary connection, the national fuuds coutributed, it appears, no less a sum than 549,796. 16s. to the expenses of this illjudged experiment. Yet it was not till 1801 that the most objectionable practice of taking children without inquiry, on a payment of £100, was formally abolished.

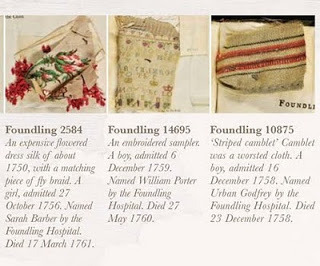

Now Knight touches upon a theme that is relevant to the Foundling Museum's current online exhibition, Threads of Feeling.

"Tokens.—It will be seen, that one of the regulations at the outset was, that persons leaving children should "affix on them some particular writing, or other distinguishing mark or token." Forty years ago, the Governors being curiously inclined, appointed a committee to inspect these tokens, with the view of ascertaining their general nature, which committee, having examined a portion of them, reported the following to be specimens of the whole: viz.—A half-crown, of the reign of Queen Anne, with hair.An old silk purse.A silver fourpence and an ivory fish.A stone cross, set in silver.A shilling, of the reign of James the Second.A silver fourpence of William and Mary, and a silver penny of King James.A silver fourpence.A small gold locket.A silver coin (foreign), of sixpence value.

"In 1757, a lottery ticket was given in with a child, but whether it turned up a prize or a blank is not recorded. The following lines were pinned to the clothes of one of the deserted infants :—

"Go, gentle babe, thy future life be spent In virtuous purity and calm content; Life's sunshine bless thee, and no anxious care Sit on thy brow, and draw the falling tear; Thy country's grateful servant may'st thou prove, And all thy life be happiness and love."

"Another child, received on the first day of admission, had the following doggrel lines affixed to its clothes:—

"Pray use me well, and you shall find My father will not prove unkind Unto that nurse who's my protector, Because he is a benefactor."

copyright Needleprint

copyright Needleprint"At this period, the station in life of the parties availing themselves of the charity, could only be surmised by the quality of the garments in which the children were dressed, the particulars of which were faithfully recorded; the following being a sample, viz.—

"1741.—A male child, about two months old, with white dimity sleeves, lined with white, and tied with red ribbon."

"A female child, aged about six weeks, with a blue figured ribbon, and purple and white printed linen sleeves, turned up with red and white."

"A male child, about a fortnight old, very neatly dressed; a fine holland cap, with a cambric border, white corded dimity sleeves, the shirt ruffled with cambric."

"A male child, a week old; a holland cap, with a plain border, edged biggin and forehead-cloth, diaper bib, striped and flowered dimity mantle, and another holland one; India dimity sleeves, turned up with stitched holland, damask waistcoat, holland ruffled shirt."

As to the matter of naming such a large number of infants, Knight explains -

"It has been the practice of the Governors, from the earliest period of the Hospital to the present time, to name the children at their own will and pleasure, whether their parents should have been known or not.At the baptism of the children first taken into the Hospital, which was on the 29th March, 1741, it is recorded, that "there was at the ceremony a fine appearance of persons of quality and distinction: his Grace the Duke of Bedford, our President, their Graces the Duke and Duchess of Richmond, the Countess of Pembroke, and several others, honouring the children with their names, and being their sponsors.

"Thus the register of this period presents the courtly names of Abercorn, Bedford, Bentinck, Montague, Marlborough, Newcastle, Norfolk, Pomfret, Pembroke, Richmond, Vernon, etc.. etc., as well as those of numerous other living individuals, great and small, who at that time took an interest in the establishment. When these names were exhausted, the authorities stole those of eminent deceased personages, their first attack being upon the church. Hence we have a Wickliffe, Huss, Ridley, Latimer, Laud, Sancroft, Tillotson, Tennison, Sherlock, etc., etc. Then come the mighty dead of the poetical race, viz.—Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakspeare, John Milton, etc. Of the philosophers, Francis Bacon stands pre-eminently conspicuous. As they proceeded, the Governors were more warlike in their notions, and brought from their graves Philip Sidney, Francis Drake, Oliver Cromwell, John Hampden, Admiral Benbow, and Cloudesley Shovel. A more peaceful list followed this, viz.—Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony Vandyke, Michael Angelo, and Godfrey Kneller; William Hogarth, and Jane, his wife, of course not being forgotten. Another class of names was borrowed from popular novels of the day, which accounts for Charles Allworthy, Tom Jones, Sophia Western, and Clarissa Harlowe. The gentle Isaac Walton stands alone.

"So long as the admission of children was confined within reasonable bounds, it was an easy matter to find names for them; but during the " parliamentary era" of the Hospital, when its gates were thrown open to all comers, and each day brought its regiment of infantry to the establishment, the Governors were sometimes in difficulties; and when this was the case, they took a zoological view of the subject, and named them after the creeping things and beasts of the earth, or created a nomenclature from various handicrafts or trades. In 1801, the hero of the Nile and some of his friends honoured the establishment with a visit, and stood sponsors to several of the children. The names given on this occasion were Baltic Nelson, William and Emma Hamilton, Hyde Parker, etc.

"Up to a very late period the Governors were sometimes in the habit of naming the children after themselves or their friends; but it was found to be an inconvenient and objectionable course, inasmuch as when they grew to man and womanhood, they were apt to lay claim to some affinity of blood with their nomenclators. The present practice therefore is, for the Treasurer to prepare a list of ordinary names, by which the children are baptized.

© Coram Family in the care of the Foundling Museum

© Coram Family in the care of the Foundling Museum "The children are all disposed of by apprenticeship: the girls at the age of fifteen to domestic service, for a term of five years, and the boys at the age of fourteen as mechanics, &c. for a term of seven years. The trades to which the latter have been apprenticed during the last seven years are as follows, viz.:— tailors, sixteen; boot and shoe makers, sixteen; fishermen, seven; cabinet makers, four; linen drapers, three; confectioners, two; bakers, two; gold beaters, two; hair dressers, three; hair manufacturers, two; silver smith, one; opticians, two; tin plate worker and ironmonger, 'one; general provision dealer, one; weaver, one; law writers, two; watch maker, one; pawnbrokers, three; soda water manufacturer, one; cooper, one; dyer, one; paper hanger, one; furnishing undertaker, one; brass, copper, and iron wire drawer, one; silk hat manufacturer, one; domestic service, four; in all eighty apprentices. A very satisfactory report was recently made of their conduct and destination, four only excepted. These have left their masters, owing to disagreements; but are believed to be leading reputable lives.

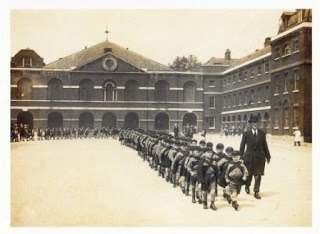

Girls exercising at the London Foundling Hospital

Girls exercising at the London Foundling Hospital © Coram Family in the care of the Foundling Museum

With respect to the girls, it appeared by a recent investigation, that of all those apprenticed during the last five years, there was only one whose conduct had been faulty, and she was redeeming her character by subsequent good behaviour.

Boys marching out of the London Foundling Hospital for the last time, 1926 © Coram in the care of the Foundling Museum

Boys marching out of the London Foundling Hospital for the last time, 1926 © Coram in the care of the Foundling Museum Whilst running a charity of such a size was not without its problems, some might say horrors, over the centuries, thousands of children's lives were saved: some 27,000 children, before the 1952 Children Act changed the way charities operated. The Foundling Hospital finally closed its doors in 1954 and became the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, which continues to benefit the children of London to this day.

Published on May 27, 2011 00:28

May 26, 2011

The Darker Side of London History - Captain Coram and the Foundling Hospital

copyright The Foundling Museum

copyright The Foundling Museum

Recently, Janet Mullany at Risky Regencies did a post on websites of interest, one of them being a link to the Threads of Feeling online exhibition mounted by the Foundling Museum in London, which allows you to view fabrics that illustrate the moment of parting as mothers left their babies at the original Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children's charity Coram.

From the Museum's website - "In the cases of more than 4,000 babies left between 1741 and 1760, a small object or token, usually a piece of fabric, was kept as an identifying record. The fabric was either provided by the mother or cut from the child's clothing by the hospital's nurses. Attached to registration forms and bound up into ledgers, these pieces of fabric form the largest collection of everyday textiles surviving in Britain from the 18th Century.

"John Styles Research Professor in History at the University of Hertfordshire received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council to curate the exhibition. John comments: "The process of giving over a baby to the hospital was anonymous. It was a form of adoption, whereby the hospital became the infant's parent and its previous identity was effaced. The mother's name was not recorded, but many left personal notes or letters exhorting the hospital to care for their child. Occasionally children were reclaimed. The pieces of fabric in the ledgers were kept, with the expectation that they could be used to identify the child if it was returned to its mother.

The textiles are both beautiful and poignant, embedded in a rich social history. Each swatch reflects the life of a single infant child. But the textiles also tell us about the clothes their mothers wore, because baby clothes were usually made up from worn-out adult clothing. The fabrics reveal how working women struggled to be fashionable in the 18th Century."

Captain Thomas Coram painted by William Hogarth 1740

Captain Thomas Coram painted by William Hogarth 1740

The Foundling Hospital in London began as the mission of retired sea captain Thomas Coram, who was appalled at the number of abandoned babies in the City. It took Captain Coram 17 years to raise the necessary money to build The Foundling Hospital as "an hospital for exposed and deserted children" to which destitute mothers brought their babies. AThe artist William Hogarth joined the cause and attracted benefactors by hanging many of his valuable paintings in the building and thereby founding the first London Art Gallery; and Handel gave fundraising concerts in the Hospital Chapel, which included a special Foundling Anthem and the music of Messiah. Coram's efforts were finally recognized by King George II who, in 1739, gave Coram a Royal Charter to create the Foundling Hospital.

No man could have undertaken a cause with a greater need, nor with such good intentions. Unfortunately, the sheer numbers of abandoned and unwanted children led to pitfalls the kind hearted Coram could not have forseen.

From Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital by John Brownlow (1847)

"When a Foundling Hospital was established in Paris, in the year 1640, its objects were limited to the children found exposed in that city, and its suburbs; and it was understood by those who furthered a similar design in this country, that its operation would, in the same manner, be confined to London and its environs. But benefits so tempting being irresistable to persons in country towns, they were determined to share with the good people of London, a privilege which they considered common to all. "There is set up in our Corporation " (writes a correspondent from a town three hundred miles distant, in one of the chronicles of the day), " a new and uncommon trade, namely, the conveying children to the Foundling Hospital. The person employed in this trade is a woman of notoriously bad character. She undertakes the carrying of these children at so much per head. She has, I am told, made one trip already; and is now set upon her journey with two of her daughters, each with a child on her back." The writer then very properly suggests, that it ought to be ascertained "whether or not these poor infants do really arrive at their destination, or what becomes of them." That such an inquiry was necessary, there is no doubt;—the sequel will prove it.

"At Monmouth, a person was tried for the murder of his child, which was found drowned with a stone about its neck! when the prisoner proved that he delivered it to a travelling tinker, who received a guinea from him to carry it to the Hospital. Nay, it was publicly asserted in the House of Commons, that one man who had the charge of five infants in baskets, happened in his journey to get intoxicated, and lay all night asleep on a common; and in the morning he found three of the five children he had in charge actually dead! Also, that of eight infants brought out of the country at one time in a waggon, seven died before it reached London: the surviving child owing its life to the solicitude of its mother; who rather than commit it alone to the carrier, followed the waggon on foot, occasionally affording her infant the nourishment it required.

"It was further stated, that a man on horseback, going to London with luggage in two panniers, was overtaken at Highgate, and being asked what he had in his panniers, answered, "I have two children in each: I brought them from Yorkshire for the Foundling Hospital, and used to have eight guineas a trip; but lately another man has set up against me, which has lowered my price."

copyright This Butterfly Mind

copyright This Butterfly Mind

In his Knight's Cyclopædia of London (1851) Charles Knight explains more about this dark trade in children and how children were received at the Hospital:

"During the period from the establishment of the Hospital to about five years after the death of Coram the applications for admission were so constantly beyond the number that the funds would admit, that the Governors ultimately determined to petition Parliament for assistance. It received the application favourably, and on the 6th of April, 1756, granted the sum of .£10,000, on the condition that all children under a certain age (first two months, then six, and lastly, as at present, twelve) should be received. And now commenced a state of things that had well-nigh utterly destroyed the institution, and which for a time caused it to be looked on, and at unjustly, as the greatest curse in the shape of a blessing that well-meant charity had ever inflicted. To make the act of application as agreeable as possible, a basket was hung at the gate, and all the trouble imposed on parents was the ringing of a bell, as they deposited their little burdens, to inform the officers of the act. Prostitution was never before, in England at least, made so easy. The new system began on the 2nd of June, 1756, on which day 117 children were received, and before the close of the year the vast number of 1,783 were adopted by the institution. Far from being frightened at this army of infants so suddenly put under their care, the Govenors appear to have been apprehensive of being neglectful of the uses and capacites of the institution; for in the following June appeared advertisements in the chief public papers, and notices at the end of every street, informing all who were concerned how very widely open were the Hospital gates. Such attention was not ill bestowed; 3727 children were admitted that year, and in all, during the three years and ten months this precious system lusted, nearly 15,000 infants were received into The Foundling Hospital! And now for some of the consequences. "There is set up in our corporation (writes a correspondent from a town three hundred miles distant in one of the chronicles of the day) a new and uncommon trade, namely, the conveying children to the Foundling Hospital. The person employed in this trade is a woman of a notoriously bad character. She undertakes the carrying of these children at so much per head. She has, I am told, made one trip already, and is now set upon her journey with two of her daughters, each with a child on her back." From another quarter we learn that the charge for bringing up children from Yorkshire, four in two panniers slung across a horse's back, was for some time eight guineas a trip, but competition had in that, as in other pursuits, lowered the price. It was perhaps to make up for the reduction in the profits that certain carriers, before leaving the children, actually stripped the little creatures naked for the sake of the value of their clothing, and thus left them in the basket! The same authority also states that out of eight babes brought up from the country for the Foundling Hospital at one time in a waggon, seven died before it reached London."

Here we return to Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital

"This practice of transporting children from remote towns was condemned by a distinct resolution of the House of Commons, and a Bill was ordered to be brought in to prevent it; but this Bill was never presented, so that parish officers and others still continued to carry on their illicit trade, by delivering children to vagrants, who, for a small sum of money, undertook the task of conveying them to the Hospital, although they were in no condition to take care of them, whereby numbers perished for want, or were otherwise destroyed; and even in cases where children were really left at the Hospital, the barbarous wretches who had the conveying of them, not content with the gratuity they received, stript the poor infants of their clothing into the bargain, leaving them naked in the basket at the Hospital gate.*

"A system so void of all order and discretion, must necessarily have occasioned many difficulties: for instance, it frequently happened, that persons who sent their children to the Hospital, having nothing to prove their reception, were suspected, or, if not suspected, were charged by their malevolent neighbours with destroying them, and were consequently cited before a magistrate of the district to shew to the contrary. This they could only do by procuring an examination of the Hospital registers; and the Governors were frequently called upon for certificates of the fact, before the party could be released. This inconvenience was, however, afterwards obviated, by the practice of giving a billet to each person who brought a child, acknowledging its reception.

"* The following is a strong instance of the vicissitudes of life :—A few years since, an aged Banker in the north of England, received into the Hospital at the above period, was desirous of becoming acquainted with his origin, when, all the information afforded by the books of the establishment was, that he was put into the basket at the gate naked."

Part Two Tomorrow!

copyright The Foundling Museum

copyright The Foundling MuseumRecently, Janet Mullany at Risky Regencies did a post on websites of interest, one of them being a link to the Threads of Feeling online exhibition mounted by the Foundling Museum in London, which allows you to view fabrics that illustrate the moment of parting as mothers left their babies at the original Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children's charity Coram.

From the Museum's website - "In the cases of more than 4,000 babies left between 1741 and 1760, a small object or token, usually a piece of fabric, was kept as an identifying record. The fabric was either provided by the mother or cut from the child's clothing by the hospital's nurses. Attached to registration forms and bound up into ledgers, these pieces of fabric form the largest collection of everyday textiles surviving in Britain from the 18th Century.

"John Styles Research Professor in History at the University of Hertfordshire received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council to curate the exhibition. John comments: "The process of giving over a baby to the hospital was anonymous. It was a form of adoption, whereby the hospital became the infant's parent and its previous identity was effaced. The mother's name was not recorded, but many left personal notes or letters exhorting the hospital to care for their child. Occasionally children were reclaimed. The pieces of fabric in the ledgers were kept, with the expectation that they could be used to identify the child if it was returned to its mother.

The textiles are both beautiful and poignant, embedded in a rich social history. Each swatch reflects the life of a single infant child. But the textiles also tell us about the clothes their mothers wore, because baby clothes were usually made up from worn-out adult clothing. The fabrics reveal how working women struggled to be fashionable in the 18th Century."

Captain Thomas Coram painted by William Hogarth 1740

Captain Thomas Coram painted by William Hogarth 1740The Foundling Hospital in London began as the mission of retired sea captain Thomas Coram, who was appalled at the number of abandoned babies in the City. It took Captain Coram 17 years to raise the necessary money to build The Foundling Hospital as "an hospital for exposed and deserted children" to which destitute mothers brought their babies. AThe artist William Hogarth joined the cause and attracted benefactors by hanging many of his valuable paintings in the building and thereby founding the first London Art Gallery; and Handel gave fundraising concerts in the Hospital Chapel, which included a special Foundling Anthem and the music of Messiah. Coram's efforts were finally recognized by King George II who, in 1739, gave Coram a Royal Charter to create the Foundling Hospital.

No man could have undertaken a cause with a greater need, nor with such good intentions. Unfortunately, the sheer numbers of abandoned and unwanted children led to pitfalls the kind hearted Coram could not have forseen.

From Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital by John Brownlow (1847)

"When a Foundling Hospital was established in Paris, in the year 1640, its objects were limited to the children found exposed in that city, and its suburbs; and it was understood by those who furthered a similar design in this country, that its operation would, in the same manner, be confined to London and its environs. But benefits so tempting being irresistable to persons in country towns, they were determined to share with the good people of London, a privilege which they considered common to all. "There is set up in our Corporation " (writes a correspondent from a town three hundred miles distant, in one of the chronicles of the day), " a new and uncommon trade, namely, the conveying children to the Foundling Hospital. The person employed in this trade is a woman of notoriously bad character. She undertakes the carrying of these children at so much per head. She has, I am told, made one trip already; and is now set upon her journey with two of her daughters, each with a child on her back." The writer then very properly suggests, that it ought to be ascertained "whether or not these poor infants do really arrive at their destination, or what becomes of them." That such an inquiry was necessary, there is no doubt;—the sequel will prove it.

"At Monmouth, a person was tried for the murder of his child, which was found drowned with a stone about its neck! when the prisoner proved that he delivered it to a travelling tinker, who received a guinea from him to carry it to the Hospital. Nay, it was publicly asserted in the House of Commons, that one man who had the charge of five infants in baskets, happened in his journey to get intoxicated, and lay all night asleep on a common; and in the morning he found three of the five children he had in charge actually dead! Also, that of eight infants brought out of the country at one time in a waggon, seven died before it reached London: the surviving child owing its life to the solicitude of its mother; who rather than commit it alone to the carrier, followed the waggon on foot, occasionally affording her infant the nourishment it required.

"It was further stated, that a man on horseback, going to London with luggage in two panniers, was overtaken at Highgate, and being asked what he had in his panniers, answered, "I have two children in each: I brought them from Yorkshire for the Foundling Hospital, and used to have eight guineas a trip; but lately another man has set up against me, which has lowered my price."

copyright This Butterfly Mind

copyright This Butterfly MindIn his Knight's Cyclopædia of London (1851) Charles Knight explains more about this dark trade in children and how children were received at the Hospital:

"During the period from the establishment of the Hospital to about five years after the death of Coram the applications for admission were so constantly beyond the number that the funds would admit, that the Governors ultimately determined to petition Parliament for assistance. It received the application favourably, and on the 6th of April, 1756, granted the sum of .£10,000, on the condition that all children under a certain age (first two months, then six, and lastly, as at present, twelve) should be received. And now commenced a state of things that had well-nigh utterly destroyed the institution, and which for a time caused it to be looked on, and at unjustly, as the greatest curse in the shape of a blessing that well-meant charity had ever inflicted. To make the act of application as agreeable as possible, a basket was hung at the gate, and all the trouble imposed on parents was the ringing of a bell, as they deposited their little burdens, to inform the officers of the act. Prostitution was never before, in England at least, made so easy. The new system began on the 2nd of June, 1756, on which day 117 children were received, and before the close of the year the vast number of 1,783 were adopted by the institution. Far from being frightened at this army of infants so suddenly put under their care, the Govenors appear to have been apprehensive of being neglectful of the uses and capacites of the institution; for in the following June appeared advertisements in the chief public papers, and notices at the end of every street, informing all who were concerned how very widely open were the Hospital gates. Such attention was not ill bestowed; 3727 children were admitted that year, and in all, during the three years and ten months this precious system lusted, nearly 15,000 infants were received into The Foundling Hospital! And now for some of the consequences. "There is set up in our corporation (writes a correspondent from a town three hundred miles distant in one of the chronicles of the day) a new and uncommon trade, namely, the conveying children to the Foundling Hospital. The person employed in this trade is a woman of a notoriously bad character. She undertakes the carrying of these children at so much per head. She has, I am told, made one trip already, and is now set upon her journey with two of her daughters, each with a child on her back." From another quarter we learn that the charge for bringing up children from Yorkshire, four in two panniers slung across a horse's back, was for some time eight guineas a trip, but competition had in that, as in other pursuits, lowered the price. It was perhaps to make up for the reduction in the profits that certain carriers, before leaving the children, actually stripped the little creatures naked for the sake of the value of their clothing, and thus left them in the basket! The same authority also states that out of eight babes brought up from the country for the Foundling Hospital at one time in a waggon, seven died before it reached London."

Here we return to Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital

"This practice of transporting children from remote towns was condemned by a distinct resolution of the House of Commons, and a Bill was ordered to be brought in to prevent it; but this Bill was never presented, so that parish officers and others still continued to carry on their illicit trade, by delivering children to vagrants, who, for a small sum of money, undertook the task of conveying them to the Hospital, although they were in no condition to take care of them, whereby numbers perished for want, or were otherwise destroyed; and even in cases where children were really left at the Hospital, the barbarous wretches who had the conveying of them, not content with the gratuity they received, stript the poor infants of their clothing into the bargain, leaving them naked in the basket at the Hospital gate.*

"A system so void of all order and discretion, must necessarily have occasioned many difficulties: for instance, it frequently happened, that persons who sent their children to the Hospital, having nothing to prove their reception, were suspected, or, if not suspected, were charged by their malevolent neighbours with destroying them, and were consequently cited before a magistrate of the district to shew to the contrary. This they could only do by procuring an examination of the Hospital registers; and the Governors were frequently called upon for certificates of the fact, before the party could be released. This inconvenience was, however, afterwards obviated, by the practice of giving a billet to each person who brought a child, acknowledging its reception.

"* The following is a strong instance of the vicissitudes of life :—A few years since, an aged Banker in the north of England, received into the Hospital at the above period, was desirous of becoming acquainted with his origin, when, all the information afforded by the books of the establishment was, that he was put into the basket at the gate naked."

Part Two Tomorrow!

Published on May 26, 2011 00:54

May 25, 2011

Tea With The Harringtons

From The Letter Bag of Lady Stanhope

. . . . . It was in the Harrington branch that the foibles of the beau monde were cultivated with intention.

Jane Fleming, later Countess of Harrington

Jane Fleming, later Countess of Harringtonby Sir Joshua Reynolds

Charles, 3rd Earl of Harrington, born the same year as Charles, 3rd Earl Stanhope, had married Jane, daughter and heiress of Sir John Fleming, Bt., who proved no unworthy successor to her celebrated predecessor immortalised by George Selwyn for vivacity and abnormal conversational powers. The drawingroom of this later Lady Harrington was recognised as a great social centre where her friends could meet, if not actually without invitation, at least at a shortness of notice which marked the informality of the entertainment and lent to it a subtle charm. The hostess, whose energy was unbounded, would go out in the morning and pay about thirty calls, leaving at each house an invitation bidding her friends to assemble at Harrington House that same evening.

Bond Street

Bond StreetShe would then walk up Bond Street at the hour at which the fashionable young men of the day were likely to be abroad, and would dart from one side of the road to the other as she spied a suitable object for her purpose. A circle of friends assembled thus three or four times a week, resulted in the formation of a recognised clique, the delightful informality of which was much appreciated by her young relations from Grosvenor Square, and the entrte into which was much envied by those who were admitted only to the larger and more stately parties reserved for the less favoured.

Charles Stanhope, Earl of Harrington

Charles Stanhope, Earl of Harringtoncopyright 1st Art Gallery

Nor were Lady Harrington's impromptu evening assemblies less celebrated than her perpetual teadrinkings at Harrington House. The superior quality of this expensive beverage in which the family of Stanhope indulged there, and the frequency with which Lady Harrington presented it to her visitors at all hours of the day, gave rise to the saying that where you saw a Stanhope, there you saw a tea-pot. A story current in town was that when her son, General Lincoln Stanhope, returned home after a prolonged absence in India, he found the family party precisely as he had left them many years before, seated in the long gallery sipping their favourite refreshment. On his entry, his father looked up from this absorbing occupation, and, with a restraint indicative of the highest breeding, gave voice to the characteristic greeting—" Hullo! Linky, my dear boy, you are just in time for a cup of tea!"

Votaries of Fashion. St. James's

Votaries of Fashion. St. James's Lord Petersham, etc. (Charles Stanhope, 4th Earl of Harrington)

copyright National Portrait Gallery

Such a home was the very atmosphere in which to develop a fashionable man of the period; and the eldest son of the House, Charles, Lord Petersham, did not discredit his surroundings. Tall, handsome, and faultlessly clad, he was one of the most celebrated dandies of his day. Decidedly affected in his manners, he spoke with a slight lisp; and since he was said to recall the pictures of Henri IV., he endeavoured to accentuate this likeness by cultivating a pointed beard. He never went out till six in the evening, and one of his hobbies indoors was the strenuous manufacture of a particular sort of blacking which, he always maintained, once perfected, would surpass every other. His sitting-room emphasized his eccentricity. One side of it represented the family penchant, being covered with shelves upon which were placed canisters containing the most expensive and perfect kinds of tea. On the other, in beautiful jars, reposed an equally choice and varied assortment of snuffs. Lord Petersham's snuff-boxes and his canes were alike celebrated; indeed, his collection of the former was said to be the finest in England, and he was reported to have a fresh box for every day in the year. Thus Gronow relates that once when a light Sevres box which he was using, was admired, Lord Petersham responded with a gentle lisp—" Yes, it is a nice summer box—but would certainly be inappropriate for winter wear!"

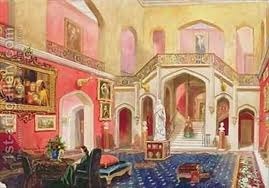

Interior of Harrington House

Interior of Harrington House copyright 1st Art GalleryCaricatures of the period represent the heir to the Earldom of Harrington clad in light trousers and a brown coat, seated upon a brown prancing horse. One of his whims, indeed, was to affect everything brown in hue—brown steeds, brown liveries, brown carriages, brown harness and brown attire. This was attributed to the fact of his having been in love with a fair widow of the name of Brown, whose charms he thus endeavoured to immortalise; but whatever the truth of this rumour, it is evident from the letter of Marianne Stanhope, that at the age of twenty-five he honoured with his devoted attention a lady whose personal attractions and unamiable disposition afforded a fund of entertainment to his relations living next door to her in Grosvenor Square. And this sidelight on the character of the dandy gives pause to criticism. How much, perhaps, of the eccentricity for which Lord Petersham was remarkable, like that of the celebrated Lady Hester Stanhope, may be attributed to the buffetings of a secret fate? Yet, this man who, with exceptional abilities and exceptional opportunity for exercising those abilities, could contentedly fill his empty days with the manufacture of blacking, or pass an entire night, as Gronow relates him to have done, playing battledore and shuttlecock for a wager with Ball Hughes, was, in much, a typical product of his generation. His mannerisms were accepted by his contemporaries with a forbearance which bordered on admiration, and, however childish his peculiarities, he remained unalterably popular.

Published on May 25, 2011 00:02

May 23, 2011

Do You Know About All Creatures Great and Small?

I've been spending time lately watching the All Creatures Great and Small Complete Series Collection that I recently purchased (28 disks worth) and am enjoying them all immensely. Again. The characters, from Seigfried and James to Tristan, Helen and Mrs Pumphrey and her Pekinese, Tricki Woo, are all a delight to revisit and to pass time with. The Yorkshire farmers the vets encounter during the course of their practice are real characters, at times funny, at others infuriating, but always entertaining.

James Herriot

James HerriotThe television series was based on the books by British veterinarian Alf Wight, who wrote under the pseudonym of James Herriot and is set in the fictional Yorkshire town of Darrowby, where the vets practice at Skeldale House surgery.

At the head of the practice is Siegfried Farnon, played by Robert Hardy (Sense and Sensibility) whose contrary nature and huge heart both often cause consternation for all concerned. Working alongside him is the younger James Herriot, who moves from Scotland to Yorkshire in order to join the practice.

Siegfried's younger brotherTristan muddles his way through veterinary school and eventually graduates, working sometimes at the practice, at other times for the Department of Agriculture. What Tristan is always most serious about are girls and beer. He is generally acknowledged as being the best customer at the local pub, the Drover's Inn. "I wouldn't treat a mad dog the way he treats his liver," mutters Siegfried. Never taking life too seriously, Tristan also has the habit of answering the practice telephone in a Chinese accent. Occasionally, those phone calls will necessitate his actually having to trudge out, often at night, in order to do vet-like things, which always elicits a grumble - i.e. "I know all about that ruddy pig; it's a killer! It's also pitch dark. What am I supposed to do, hold a torch in one hand and a lancet in the other while it disembowels me?"

James is the steady partner, the one who takes on morning surgeries in place of a hungover Tristan, the man who can be relied upon for good judgment and a mature attitude. Unless, he's anywhere near Granville Bennett, a nearby veterinary surgeon with whom they occasionally work. Granville has a wooden leg when it comes to liquor and, more diasterously, the power to persuade James into drinking more than his fill, despite James's good intentions. Helen, James's patient and long suffering wife, is always on hand to offer sustenance, as well as a few well deserved barbed comments.

All Creatures Great and Small is filled with gentle humour, appealing characters, the Yorkshire dales and some of the best photography of it's time - people were astounded at how realistic the scenes involving veterinary treatments and live animal births were made to seem.

This past December, BBC announced that it will begin production on Young James, a prequel drama inspired by the true story of how the world's most famous vet, "James Herriot" came to learn his trade in Scotland. Drawing on an amazing archive and exclusive access to the diaries and case notes Herriot kept during his student days in Glasgow, as well as the biography written by his son.

Cast of the original, television series

James Herriot — Christopher Timothy

Siegfried Farnon — Robert Hardy

Tristan Farnon — Peter Davison (series 1-5, 7)

Helen Herriot — Carol Drinkwater (series 1-3 and specials)

and Lynda Bellingham (series 4-7)

Mrs Pumphrey — Margaretta Scott (recurring)

Visit The World of James Herriot Museum website here.

Published on May 23, 2011 00:32

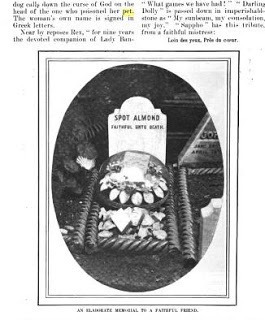

The Hyde Park Pet Cemetery

Founded in 1880 and now largely hidden behind thick undergrowth, Hyde Park's pet cemetery is home to over 300 deceased pets, including dogs, cats, birds and even a monkey. Curious visitors can book an appointment to view it through the Hyde Park police. However, for a 19th century description of the cemetery we turn to The Puritan, Volume 9, (1901) which can be found at Google Books and which we quote below:

A CEMETERY FOR DOGS.

BY BERTHA DAMARIS KNOBE.

A CURIOUS LITTLE GRAVEYARD IN THE HEART OF LONDON, OFFERING QUAINT TESTIMONY OF MAN'S AFFECTION FOR HIS DOG.

This burial ground for dogs, oddly enough, is conspicuously placed in Hyde Park. One day, the keeper of the lodge at Victoria Gate—that is, the man who was keeper nineteen years ago—was tearfully importuned to dig a grave in his flower garden for a fox terrier belonging to an aristocratic resident. Thereupon it became the custom for dogs of high degree in that locality to have a first class funeral and interment. That the London officials have allowed it, centrally located as it is, to remain undisturbed is due, there is no doubt, to the fact that Queen Victoria has the dogs who serve as her faithful companions carefully buried in a sequestered spot at Windsor Castle.

This city of the canine dead is an attractive spot. It is the conventional cemetery in miniature, with more foliage, perhaps, which makes a pleasing setting to the glistening white tombstones. It is entirely inclosed with well trimmed bushes and young trees, so that the passer by in the street is prevented from peering through the park fence into the sacred precinct. Even the would be visitor must secure a permit from the brass buttoned keeper of the lodge.

Once inside, one sees narrow walks laid out with regularity, and on either side rows upon rows of little graves, each small lot being marked off with bars of brown earthernware. The graves are covered with sod or ivy, while on some flowers have been planted. In one corner is a tiny greenhouse, where the mourning master may purchase a floral emblem.

For a dog to repose peacefully in this resting place does not cost an excessive sum. There is a tinge of charity about it all. for if a poor washerwoman conies along, as one did not long ago, with a common cur rolled up in her apron and a big lump in her throat, the kind hearted keeper of the lodge buries her dog for nothing. If the owner is well to do, and the pampered pet has been fed on pate de foies gras all his life, a corresponding charge is made.

In this cemetery some of the deceased adorned with the most curious tokens. There are shells bleached to whiteness, glass cases in which are wreaths—these cheap gewgaws are so common in all European cemeteries—and on one is a string of New Zealand shells, which a man placed over the mortal remains of his dog to signify that as long as they last love shall endure. After the owner has decorated the grave, it is not uncommon for him to order a photograph of it.

As to the epitaphs, they are undoubtedly the oddest contributions to graveyard literature. There are inscriptions in Egyptian and Italian, in poetry and prose, or. oftener still, some endearing term which was evidently in use before his dogship left for the happy hunting ground. One of the first epitaphs to attract the eye has a Biblical peroration. It reads: In loving memory of M. C. Trotter's Jessie. Born 1893, died 1900. "Not one of them is forgotten before God."- Luke xii, 6. Another reads: In fond memory of Gyp —" my Gippie "—who died February 1, 1899, aged seven years. He was a true little friend and companion, and will never be forgotten by his sorrowing mistress, M. B.

The owner of " Hetty " adds this to the usual dates of birth and death: And when at length my own life's work is o'er I hope to find her watching as of yore. Eager, expectant, glad to meet me at the door.

One of the most popular inscriptions —it is found on at least three tombstones—is the quotation:

There are men both good and wise who say that dumb creatures we have cherished here below shall give us kindly greeting when we pass the Golden Gate. Is it folly if we hope it may be so?

Close by is "' Poor little Prince," who was the pet of the Duchess of Cambridge, while "Pitkin" not only has an " Au Revoir," but the crest of the grand duke to whom he belonged. One woman went so far as to engrave on her dog's stone: She brought the sunshine into our lives, but she took it away with her.

Aside from the inscriptions, which are nothing if not unique, are interesting little tales connected with some of these dogs. The most pretentious stone in the cemetery—the majority are simple —was erected by a rich voting woman who was devoted to her "Lily." When this pet passed on, she purchased a good sized monument, the shaft of which is entwined with lilies. Around this grave are a stone coping and an iron railing, while a profusion of fresh flowers adorns the mound, the doting mistress being addicted to periodically slipping away from pink teas to leave a tear and a token over the remains of " Lily."

One mourning mistress adds "Faithful unto death" to "Spot Almond" and in a glass case which reposes on the grave are not only the conventional wax flowers, hut this message, written: In ever loving memory of our loving, faithful dog, Spot, for five years a faithful friend and companion of her devoted mistress, who will ever mourn her loss. Gone, but will never be forgotten.

Not one of the canary birds has a stone, but a parrot, known as the best talker in England and the winner of many pounds in prizes, has a small head piece. This post mortem care of pets, which is so oddly illustrated in the London cemetery, is a counterpart of the spirit that has ever induced fine companionship between man and the dog. When it comes to fidelity, the animal is so superior that a poet has put it: Oh, much enduring dogs to live With men! To you our praise we give.

Queen Victoria is not the only crowned head who has enjoyed these four footed friends "with soft brown eyes more eloquent than speech," and after their demise ordered a respectable interment. 'There are numerous other personages, crowned and uncrowned, who have recorded their comradeship in stone. History records that Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, erected near his castle, "Sans Souci" at Potsdam, a monument to his favorite greyhound, Biche.

This care of the canine dead in London may seem overdone. But the sojourner in that metropolis is impressed with the consideration shown all living animals, from the horses hitched to the great lumbering `buses to the cats of the street. Humane societies for animals abound, and one finds everything from a horse hospital to a home for stray cats. The workingman who walked many mile at night, carrying his dog, to beseech the keeper of the dog cemetery to give it a " Christian burial," serves as a sample of the animal loving type in England. It is doubtless owing to this universal spirit of kindness for dumb creatures that the burial ground for dogs has flourished in the center of one of London's most fashionable thoroughfares.

Published on May 23, 2011 00:21

May 22, 2011

The Battle of Vimeiro, Revisited

This account is adapted from my old website, wwwvictoriahinshaw.com, and was writtten when Zebra Regency Romances published my novel Least Likely Lovers in August 2005. In the story, Major Jack Whitaker, formerly of the 22nd Foot, was severely injured in the Battle of Vimeiro, (21 August, 1808) and has come home to England to complete his recuperation, hoping to return to the front beside his comrades. However, in the meantime, Sir Arthur Wellesley (eventually to become the Duke of Wellington) has asked Jack to build support for the army among politicians and social leaders in London, an assignment that Jack finds impossibly frustrating. You won't be surprised to find that Jack finds a lady with whom he falls in love.

This account is adapted from my old website, wwwvictoriahinshaw.com, and was writtten when Zebra Regency Romances published my novel Least Likely Lovers in August 2005. In the story, Major Jack Whitaker, formerly of the 22nd Foot, was severely injured in the Battle of Vimeiro, (21 August, 1808) and has come home to England to complete his recuperation, hoping to return to the front beside his comrades. However, in the meantime, Sir Arthur Wellesley (eventually to become the Duke of Wellington) has asked Jack to build support for the army among politicians and social leaders in London, an assignment that Jack finds impossibly frustrating. You won't be surprised to find that Jack finds a lady with whom he falls in love.

The Battle of Vimeiro (also called Vimiero or Vimera) was the first major conflict of the Peninsular War, part of the greater continent-wide Napoleonic Wars. Up to Napoleon's 1807 invasion of Portugal, Britain's oldest ally, British participation in the European war had involved the navy, diplomacy, perhaps major scheming, but not many actual soldiers. When the Portuguese needed help, however, the government in London sent troops to oppose the French. They arrived in August 1808 under the leadership of Major General Sir Arthur Wellesley.

On a recent trip to Lisbon, my husband and I hired a car to take us to see the site of Battle of Vimeiro. We drove via multi-lane freeways north out of Lisbon, thinking about what a difference 200 years made in transportation. When we turned off the road, not far from Torres Vedras, we saw a primarily agricultural countryside filled with deep ravines, craggy rocks, rough pastures, and adorned with olive groves.

On a recent trip to Lisbon, my husband and I hired a car to take us to see the site of Battle of Vimeiro. We drove via multi-lane freeways north out of Lisbon, thinking about what a difference 200 years made in transportation. When we turned off the road, not far from Torres Vedras, we saw a primarily agricultural countryside filled with deep ravines, craggy rocks, rough pastures, and adorned with olive groves. The village of Vimeiro is whitewashed, with its buildings right up against the road. We looked for the promised sign to the battle's memorial but missed it. The driver had a solution to our dilemma: his friend who managed the Hotel Golf Mar on the coast, not far from the village. In fact, the hotel manager escorted us to the cliffs overlooking the Rio Maciera where the British troops landed on the sandy spits at either side of the river's mouth. I could look out at the empty sea and imagine those tall ships anchoring and the troops in their red coats climbing down the rope ladders into small boats to be rowed to the beach.

Armed with better directions, we drove back into the village past the large barn-like structure which was used as a hospital during the battle and the church, near which some skirmishing took place.

Armed with better directions, we drove back into the village past the large barn-like structure which was used as a hospital during the battle and the church, near which some skirmishing took place. With one or two deft turns, we found the park on the heights with its memorial and blue tile pictures of the battle, shown here. I walked around the park, looking out at the battle site, trying to visualize the British and French troops in their colorful uniforms, to hear the explosion of artillery and rattle of musket fire. A map of the battle overlooks the countryside from the heights. But aside from the memorial park, one would never guess this peaceful place had ever seen the deaths of hundreds of men or heard cries of the wounded.

With one or two deft turns, we found the park on the heights with its memorial and blue tile pictures of the battle, shown here. I walked around the park, looking out at the battle site, trying to visualize the British and French troops in their colorful uniforms, to hear the explosion of artillery and rattle of musket fire. A map of the battle overlooks the countryside from the heights. But aside from the memorial park, one would never guess this peaceful place had ever seen the deaths of hundreds of men or heard cries of the wounded.Our driver said in his more than twenty years of experience taking tourists around Portugal, no one had ever asked to come here before. Why, he asked, was I eager to find the site of the Battle of Vimeiro? When I told him about my novels, I imagined he thought of war stories filled with blood and gore. It probably never occurred to him that I write gentle stories of love and lifelong commitment. I wished that I had a copy of one of my novels to give him.

Left, The Church

Left, The ChurchReturning to events of 1808, Major General Wellesley had landed his troops in central Portugal, with the goal of moving south to take Lisbon from the French. They fought a battle at Rolija, August 17, 1808. After several hours of brutal combat, the French were forced back. Wellesley moved on to the Maceira River, just west of Vimeiro, where more British troops came ashore with their horses and equipment.

Four days later, about 16,000 British troops and 2,000 Portuguese defeated about 19,000 French under General Jean-Andoche Junot (1771-1813) at Vimeiro. Wellesley stationed his troops on ridges between the village and the beach on the night of August 20th. By dawn, they could see the French approaching. In the face of British fire, General Junot's men repeatedly failed to take the heights, though in various skirmishes, there was hard combat, including hand-to-hand fighting in the village. To the north of town, the French fell prey to one of Wellesley's favorite strategies: stationing his troops out of enemy sight behind the crest of a hill, then wiping out the enemy as they came over the top.

Four days later, about 16,000 British troops and 2,000 Portuguese defeated about 19,000 French under General Jean-Andoche Junot (1771-1813) at Vimeiro. Wellesley stationed his troops on ridges between the village and the beach on the night of August 20th. By dawn, they could see the French approaching. In the face of British fire, General Junot's men repeatedly failed to take the heights, though in various skirmishes, there was hard combat, including hand-to-hand fighting in the village. To the north of town, the French fell prey to one of Wellesley's favorite strategies: stationing his troops out of enemy sight behind the crest of a hill, then wiping out the enemy as they came over the top. By midday, Junot was beaten and the newly arrived British generals called an end to the firing. Wellesley advocated continuing the rout, driving the enemy out of Portugal all the way to French soil. However, as the battle had progressed, Wellesley's overly cautious superior officers came ashore; first, General Harry Burrard (1755-1813), then General Hew Dalrymple (1750-1830). They overruled Wellesley's plans to chase after the French. Thus, by allowing the French time to regroup and bring in reinforcements, the British lost their advantage. Instead, over Wellesley's objections, Burrard and Dalrymple organized a conference to negotiate with the French at Cintra (aka Sintra) several days later.

The Convention of Cintra was signed August 30, 1808, nine days after the Battle of Vimeiro. It obligated the Royal Navy to carry 26,000 French soldiers to France, with their weapons and whatever spoils they had acquired. There was no restriction against their return to fight again in Portugal. Sir Arthur Wellesley voiced his objections, but, in the end, signed the Convention. The reaction in Britain was dramatic, led by the opposition to the government and their allies in the press. Scathing articles, mocking cartoons and contemptuous speeches condemned the terms of the convention. Wellesley, along with Generals Burrard and Dalrymple, was ordered back to London. The three generals faced a hearing before a Board of Inquiry at Horseguards, beginning November 15, 1808.

The Convention of Cintra was signed August 30, 1808, nine days after the Battle of Vimeiro. It obligated the Royal Navy to carry 26,000 French soldiers to France, with their weapons and whatever spoils they had acquired. There was no restriction against their return to fight again in Portugal. Sir Arthur Wellesley voiced his objections, but, in the end, signed the Convention. The reaction in Britain was dramatic, led by the opposition to the government and their allies in the press. Scathing articles, mocking cartoons and contemptuous speeches condemned the terms of the convention. Wellesley, along with Generals Burrard and Dalrymple, was ordered back to London. The three generals faced a hearing before a Board of Inquiry at Horseguards, beginning November 15, 1808.  After extensive deliberations, the board voted on December 22, 1808, to accept the convention. The generals were officially exonerated, but neither Burrard nor Dalrymple ever saw military action again. Unofficially, all of London knew of Wellesley's reluctance, and most probably knew the story of how his plan to continue the battle and push the French back to Lisbon and out of Portugal forever was thwarted.

After extensive deliberations, the board voted on December 22, 1808, to accept the convention. The generals were officially exonerated, but neither Burrard nor Dalrymple ever saw military action again. Unofficially, all of London knew of Wellesley's reluctance, and most probably knew the story of how his plan to continue the battle and push the French back to Lisbon and out of Portugal forever was thwarted.The command in Portugal was taken over by General Sir John Moore (l). Moore died after the Battle of Corunna when French commanders chased the British troops through the mountains. Six thousand British troops, including Moore, were killed in January 1809. For more details, see this blog of May 10, 2011.

The British government in London sent Sir Arthur Wellesley back to Portugal in April 1809 with 20,000 troops to join the remaining 9,000 still there. The war continued in Portugal and Spain for another five years, ending in 1814 with Napoleon's first abdication. British troops, by then, had fought their way through Spain and into southern France. Wellesley was honored with the title of Duke of Wellington, a tribute he enhanced with his victory at Waterloo in June, 1815. Stay with us for lots more upcoming about Waterloo.

Portraits by Sir Thomas Lawrence; photos by V. Hinshaw (what a pair!)

Published on May 22, 2011 02:00

May 21, 2011

In The Garden at Eyford House

On Sunday, May 22nd, Eyford House in Upper Slaughter, Glouscestershire will play host to a giant plant sale featuring 25,000 plants on sale, local produce, a country-shopping village, sculpture garden, Light Cavalry Military Band and three garden experts - Val Bourne, Mary Keane and Roddy Llewellyn - will be on hand to answer gardening questions and offer advice. The event will benefit the ABF The Soldiers' Charity and the Countryside Alliance at Eyford.

The property, a classical Cotswolds home in idyllic grounds is where legend has it, poet John Milton was inspired to write Paradise Lost and takes the crown as England's Favourite House, according to Country Life magazine.

Charlotte Heber Percy, whose family lives at Eyford House, commented: "We are so lucky to live in this heavenly setting and love to share it with the public. The plant sale is something we are all passionate about: everyone on the committee supports country sports and the rural way of life, and we also support our brave armed forces, so this plant sale is the ideal way for us to boost both causes while providing a fun day out."

Novelist Jilly Cooper will officially open the plant sale with a ribbon cutting and eight local hunts ( the Cotswold, North Cotswold, Heythrop, Old Berks, Beaufort, Warwickshire, Berkeley and VWH hunts) have joined together to tend 25,000 plants to sell on the day. The event will make the most of what Country Life magazine has called the "pastoral idyll" of Eyford's parklands. The plant sale will include a shopping village with a range of gardeners' accessories as well as outdoor clothing and gifts for the countryside enthusiast and there will be live chickens and ducks. Jilly Cooper, who lives locally, will be signing the paperback edition of her latest blockbuster, Jump! Another local author, Duff Hart-Davis, the distinguished biographer, naturalist and journalist, will be signing copies of his latest two books, Among the Deer: In the Woods and On the Hill: A Stalker Looks Back and The War That Never Was: The True Story of the Men who Fought Britain's Most Secret Battle.

Mrs Prest (Mrs. Heber Percy's daughter), who lives at Eyford with husband Rupert and three children, said: "I am absolutely thrilled. "I always adored the house and I loved to come and stay here with my grandmother when I was a child. Each day, I pinch myself at how lucky I am to live in such a beautiful, peaceful house."

THE PLANT SALE WILL BE HELD BETWEEN 10AM AND 4PM. TICKETS £5, YOUNG CHILDREN WILL BE ADMITTED FREE OF CHARGE.[image error]

Published on May 21, 2011 00:48

May 20, 2011

Notes from Lisbon

Victoria here, writing from Lisbon, where it is sunny and delightfully breezy. Above, the statue of Marquis de Pombal, at the foot of Parque Eduardo VII, named for the British King who visited here in 1903 to confirm the continuing alliance of Portugal and the United Kindom. Below, the view from the top of the park, looking down toward the statue, the broad tree-lined boulevard beyond it, to the River Tagus.

The Marquis de Pombal (1699-1782) was a distinguished statesman who provided strong leadership after the terrible earthquake and tsunami that devastated Lisbon November 1, 1755. He also abolished slavery in Portugal and her colonies, reorganized the army and navy, and improved the administration of colonial Brazil, among other accomplishments. His statue overlooks the Avenida da Liberdade, a broad boulevard with gardens and restaurants and lined by banks, hotels and smart shops.

The sidewalks are paved with small stones, often in patterns, as along the boulevard.

We stopped for luncheon at one and sat outside under the shade of huge plane trees and beside a large palm. One of the cafe's specialities was a smoothie called Splash. Delicious.

As one strolls the Avenida, there are wonderful views up the cross streets, which lead into the hilly old town areas, most of which predate the earthquake and survived the floods.

Since we are to leave on our cruise tomorrow, we went down to the River Tagus to see the port. Across the street was the Military Museum honoring the centuries of Portuguese domination of large areas of the world Brazil, Mozambique, Goa, and Macao, to name a few. It is often pointed out here that Portuguese is the third most widely spoken European language in the world.

The museum has a huge collection of artillery, from gigantic cannons down to pistols and daggers. In the courtyard, many cannons can be see arranged in front of the story of the Portuguese in beautiful blue-and-white ceramic tiles.

Inside the museum were displays of events from the discovery of sea routes to India by Vasco DaGama through the Napoleonic invasions to World Wars I and II. Below the uniform of Portuguese troops fighting with Lord Wellington early in the Peninsular Wars.

Finally a few pictures which fail adequately to show the beauty of the blue/purple blooming trees found all over town. I think they are Jacaranda trees, a beautiful shade that reminds me of periwinkle blue. Stunning!!

[image error]

Published on May 20, 2011 00:30

May 19, 2011

John Singer Sargent - The British Portraits

John Singer Sargent, the son of an American doctor, was born in Florence in 1856. He studied painting in Italy and France and in 1884 caused a sensation at the Paris Salon with his painting of Madame Gautreau. Exhibited as Madame X, people complained that the painting was provocatively erotic.

The scandal persuaded Sargent to move to England and over the next few years established himself as the country's leading portrait painter. Sargent had no assistants; he handled all the tasks, such as preparing his canvases, varnishing the painting, arranging for photography, shipping, and documentation. He commanded about $5,000 per portrait, or about $130,000 in current dollars. Following are portraits representative of Sargent's prolific, and much prized, portraiture featurning British subjects.

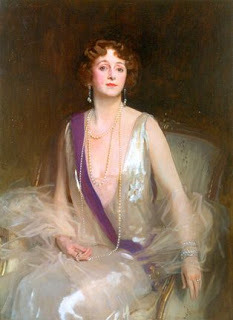

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw 1892-93 National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

In late 1892, Sargent began work on the portrait of Lady Agnew, commissioned by Andrew Noel Agnew, a barrister who had inherited the baronetcy and estates of Lochnaw in Galloway. The sitter was his young wife, Gertrude Vernon (1865-1932).

Hon. Victoria Stanley - 1899

Winifred, Duchess of Portland (Winifred Dallas-Yorke) - 1902

Countess of Warwick and Son (Frances Evelyn 'Daisy' Maynard) - 1905

The Countess of Essex - 1906

Theresa ('Nellie') Marchioness of Londonderry - 1912

Sibyl Sasson-Countess of Rocksavage (later Marchioness of Cholmondeley) - 1913

Sir Philip Sassoon - 1923 (Sybil's brother)

Tate Gallery, London

Mrs. George Nathaniel Curzon (Grace Elvina, Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston) - 1925

The Hon. Lilian Maud Glen Coats, later Duchess of Wellington

For a complete online catalogue of the works of John Singer Sargent, click here.

Published on May 19, 2011 01:16

May 18, 2011

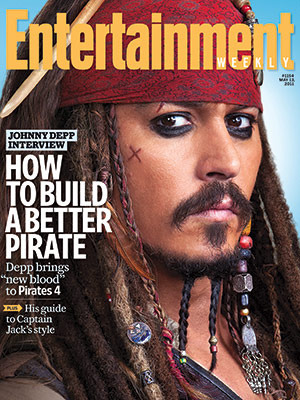

Pirates of the Caribbean - On Stranger Tides

Prepare yerselves - On Stranger Tides premiers in just two days, when all things piratical will be let loose upon a waiting populace. (Holy Captain Morgan! I just looked it up - piratical is a word) As if a drunken, debauched, slurring, kohl wearing Johnny Depp weren't enough to make a matey sit up and take notice, OST guest stars Ian McShane as Blackbeard. Yesssss!

Okay, NOT from the film, but who could resist?Speaking of his role, McShane recenly said, "It was a pleasure to shoot [On Stranger Tides]. I was only glad it finished so I could get rid of the beard! It was the heaviest thing — it was like having a dead cat around my face! It was made in three or four pieces and held on by magnets and God knows what else. It took an hour and a half to put on every day. It was sort of spectacular. He was a real biker pirate — it's all black leather." Aaaarrrggghhhh.

Okay, NOT from the film, but who could resist?Speaking of his role, McShane recenly said, "It was a pleasure to shoot [On Stranger Tides]. I was only glad it finished so I could get rid of the beard! It was the heaviest thing — it was like having a dead cat around my face! It was made in three or four pieces and held on by magnets and God knows what else. It took an hour and a half to put on every day. It was sort of spectacular. He was a real biker pirate — it's all black leather." Aaaarrrggghhhh.Blackbeard's (Edward Teach's) exploits were notorious around Nassau, in the Bahamas, which was founded around 1650 by the British as Charles Town. The town was renamed in 1695 after Fort Nassau. Due to the Bahamas' strategic location near trade routes and its multitude of islands, Nassau soon became a popular pirates' den, and British rule was soon challenged by the self-proclaimed "Privateers Republic" under the leadership of the infamous Blackbeard. However, the alarmed British soon tightened their grip, and by 1720 the pirates had been killed or driven out. Bah! I don't believe it. In fact, I'm going to Nassau in three weeks time in the hopes of finding a spare pirate or two and, with luck, buried treasure.

I'll be diving the Ruins of Atlantis and exploring the Lost City alongside sharks, spotted rays and brilliantly colored tropical fish. My daughter, Brooke, and I will also take a turn swimming with the dolphins.

When not involved in aquatic activities, I hope to revisit a favorite antiques store in Nassau, run by an Englishman. Don't laugh - last time I was there I found the edition of The London Illustrated News covering Wellington's funeral. See? There are treasures yet to be found in Nassau.

Not to mention rum.

And let us not forget that OST also stars Geoffrey Rush, who reprises his role as pirate lord Barbossa who, along with Captain Jack Sparrow, searches for the Fountain of Youth. You can watch a clip of him in action here.

Another reason to see On Stranger Tides? With some bits filmed on location in London, this installment of POTC actually has scenes set in the City and features a carriage chase through London streets.

For a refresher course on past POC flicks, visit the Wikipedia page here

100 bottles of rum in the hold, 100 bottles of rum,

You take one out and pass it about, 99 bottles of rum in the hold!

99 bottles of rum in the hold, 99 bottles of rum . . . .

Published on May 18, 2011 00:24

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.