Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 146

June 18, 2011

The Search for Paget's Leg

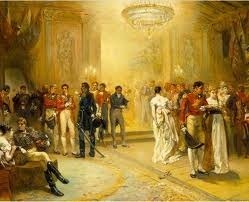

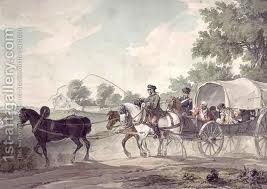

Wellington comforts Paget after his surgery at Waterloo

Wellington comforts Paget after his surgery at Waterloo

I am so glad, for so many reasons, that my very good friends are Jo Manning and Victoria Hinshaw, not least because we share the same historic interests and the same mania for researching, and visiting, little remembered facts and places in British history. Recently, Victoria kept Jo and I in thrall with the minutae of her research itinerary whilst in England via a series of rapid fire emails - where she was going, what she was researching, the research matrix she'd prepared, who her contacts were at various archives, what the train timetable was and where she'd be eating lunch. And Jo and I swooned at the prospects. In addition to shared interests, all three of us have our own, unique historic quests and we support each other fully in these, no matter how crazy they seem. Last year, my particular quest was something the three of us termed "The Search for Paget's Leg."

Being an avowed Wellington afficianado, you wouldn't think that I'd spare much energy worrying about either Henry Paget, Lord Uxbridge (created Marquis of Anglesey by Geo. IV five days after the Battle of Waterloo) or his leg, as Paget had earlier run off with Wellington's sister-in-law, his brother Henry's wife, Lady Charlotte. At the time, Paget was also married - to Lady Jersey's daughter, Lady Caroline Elizabeth Villiers, by whom he'd sired eight children. (Yes, eight - the bounder! He went on to have TEN more with Charlotte). Wellington felt the impact of this desertion as well, as it threw Henry into a decline from which he was slow to recover and, in the meantime, Wellington and his wife, Kitty, had to take care of Henry's two young children, as Henry was incapable of doing so himself.

You'll recall that last year Victoria and I embarked on a whirlwind London/Waterloo tour, during which I was most looking forward to seeing the spot in Waterloo where Paget's leg was buried. Yeah, yeah - totally nuts. But you have to bear in mind that Victoria, Jo and I are the Lucy Ricardos of historical research.

I realize that I'm writing this blog as if you already know the story behind Paget's leg. If for some odd reason you're not familiar with it, click here for the condensed version of the story. So . . . all along the route of our tour, from London to Waterloo, I'd sigh at intervals and tell Victoria, "I can't wait to see Paget's leg." After the re-enactment of the Battle of Waterloo itself, Paget's leg was to be the highlight of the tour for me. I've already admitted that this notion of mine was strange, but it becomes stranger still when you realize that Paget's leg isn't even at Wellington's headquarters in Waterloo any longer. It was disinterred and shipped back to England when Paget (Anglesey) died in 1854 and was buried along with the rest of him in St. Paul's Cathedral in London. Yes, Paget and Wellington are buried in the same place. Poor Artie couldn't shake this guy loose, even in death.

So . . . . the very last stop on the Waterloo portion of our tour was the Wellington Museum (formerly Wellington's headquarters), where, out in the back garden, stands the spot where Paget's leg (once) was. Even though the Heavens didn't direct rays of sunight onto the grave whilst I was there, nor did a choir of angels sing whilst I gazed upon it, I was in alt.

The (rather smallish) back garden

The (once) final resting place of Paget's leg

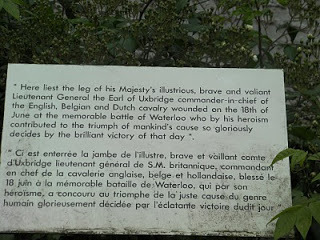

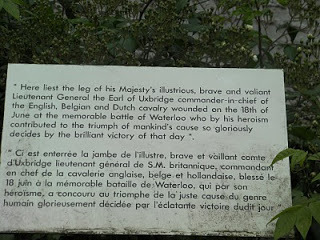

The sign by the (former) grave

The sign by the (former) grave

Of course, the grave itself was not the Holy Grail, rather it had become to me the symbol of all that was the Battle of Waterloo - the tragedy, the drama, the irony, the heartbreak and the heroics. I could have as easily fixated upon the site of the Duchess of Richmond's Ball, which would have been just as fitting, as that no longer exists, either.

So . . . what's next on my 19th century bucket list? The decoupage screen Beau Brummell was toiling away on and which was meant to be a present to his great good friend Frederica, Duchess of York. Brummell stopped working on it when news of her death reached him in France. Trouble is, I have no idea where to begin looking for it. If you're an aged aristocrat living in the back of beyond who happens to have the screen in your attic, email me. Heck, email me even if the screen only used to be in your attic. Victoria, Jo and I will then embark on what we shall no doubt call "The Quest for Brummell's Screen."

Victoria here, freshly off the plane from Heathrow and fighting a stubborn cold (you don't want to hear about it!), ready to prepare lots of material for the blog, including visits to the tomb of Sir John Moore in Spain, Walmer Castle, Trooping the Colour 2011, Strawberry Hill, and a lovely day in Windsor with Hester Davenport. And the Queen in her pink hat. However, I could not help but add to Kristine's search. And perhaps give an answer.

At Newstead Abbey, former home of the Lords Byron, and now open to tourists under the auspices of the town of Nottingham, there is a decoupage screen purportedly made by George, Lord B, himself. Perhaps this is the screen Kristine is looking for -- and if so, my dear, you have seen it already. Someplace among the piles of booklets and ephemera I have collected on my jaunts to England is a booklet which tells the story. Now to find it. Hopeless? Perhaps. Stay tuned.

Kristine's reply - Byron . . . feh. No, I'm looking for the Brummell screen. I don't remember any screen at Newstead Abbey. Methinks I was too creeped out by the place to notice much. What. A. Dump. Were decoupage screens a big fad for men at that time!? We'll have to look into it . . . can't wait to see your trip posts! Did you bring back any Wills and Kate tat for me? Did you pick up any issues of Country Life? I can't believe you were with Hester for Ascot again - two years in a row. That tears it, we'll just have to book another trip for next June and make it a triple play. Went online to see when the Wellington Conference is happening in 2013 but could find nothing. Already told Greg I'm going and asked if he wanted to come along. He gave me that look, the one where his eyes glaze over at the mention of anything Artie, so it's safe to say he won't be joining me/us in Southampton . . . . Uh, oh . . . sorry . . . forgot we were in public . . . . I'll email you the rest of my rant.

Victoria responds: You mean there are two Bs? Byron and Brummell are different guys? In my clogged brain (not to mention nasal passages), I see one well-dressed poet -- oh, no. Now I remember. The one who had his valet clean his boots with champagne (what a dreadful waste) and the one who was mad, bad and dangerous to know. So I take it all back. But it is curious about decoupaged screens and men, isn't it? Do you suppose they had classes at Eton or Cambridge? What ever happened to Queer Eye, anyway? I think I'll go back to bed. Sniff.

Kristine says - I was just thinking about Queer Eye For The Straight Guy last week! Whatever did happen to that show? I loved it. I love Carson. Did you see him on Oprah? She sent him to Bucklebury (sp?) Kate Middleton's hometown. What a hoot! I know you're still sick, but listen to me through the haze of illness . . . . Byron and Brummell are/were, indeed, two different people. And I still maintain that history recorded it incorrectly and that it was Byron who said the dangerous to know thing about that lunatic, Caro Lamb. Too bad they're separated by centuries . . . she and Lindsay Lohan would have been BFFs. [image error]

Wellington comforts Paget after his surgery at Waterloo

Wellington comforts Paget after his surgery at Waterloo I am so glad, for so many reasons, that my very good friends are Jo Manning and Victoria Hinshaw, not least because we share the same historic interests and the same mania for researching, and visiting, little remembered facts and places in British history. Recently, Victoria kept Jo and I in thrall with the minutae of her research itinerary whilst in England via a series of rapid fire emails - where she was going, what she was researching, the research matrix she'd prepared, who her contacts were at various archives, what the train timetable was and where she'd be eating lunch. And Jo and I swooned at the prospects. In addition to shared interests, all three of us have our own, unique historic quests and we support each other fully in these, no matter how crazy they seem. Last year, my particular quest was something the three of us termed "The Search for Paget's Leg."

Being an avowed Wellington afficianado, you wouldn't think that I'd spare much energy worrying about either Henry Paget, Lord Uxbridge (created Marquis of Anglesey by Geo. IV five days after the Battle of Waterloo) or his leg, as Paget had earlier run off with Wellington's sister-in-law, his brother Henry's wife, Lady Charlotte. At the time, Paget was also married - to Lady Jersey's daughter, Lady Caroline Elizabeth Villiers, by whom he'd sired eight children. (Yes, eight - the bounder! He went on to have TEN more with Charlotte). Wellington felt the impact of this desertion as well, as it threw Henry into a decline from which he was slow to recover and, in the meantime, Wellington and his wife, Kitty, had to take care of Henry's two young children, as Henry was incapable of doing so himself.

You'll recall that last year Victoria and I embarked on a whirlwind London/Waterloo tour, during which I was most looking forward to seeing the spot in Waterloo where Paget's leg was buried. Yeah, yeah - totally nuts. But you have to bear in mind that Victoria, Jo and I are the Lucy Ricardos of historical research.

I realize that I'm writing this blog as if you already know the story behind Paget's leg. If for some odd reason you're not familiar with it, click here for the condensed version of the story. So . . . all along the route of our tour, from London to Waterloo, I'd sigh at intervals and tell Victoria, "I can't wait to see Paget's leg." After the re-enactment of the Battle of Waterloo itself, Paget's leg was to be the highlight of the tour for me. I've already admitted that this notion of mine was strange, but it becomes stranger still when you realize that Paget's leg isn't even at Wellington's headquarters in Waterloo any longer. It was disinterred and shipped back to England when Paget (Anglesey) died in 1854 and was buried along with the rest of him in St. Paul's Cathedral in London. Yes, Paget and Wellington are buried in the same place. Poor Artie couldn't shake this guy loose, even in death.

So . . . . the very last stop on the Waterloo portion of our tour was the Wellington Museum (formerly Wellington's headquarters), where, out in the back garden, stands the spot where Paget's leg (once) was. Even though the Heavens didn't direct rays of sunight onto the grave whilst I was there, nor did a choir of angels sing whilst I gazed upon it, I was in alt.

The (rather smallish) back garden

The (once) final resting place of Paget's leg

The sign by the (former) grave

The sign by the (former) graveOf course, the grave itself was not the Holy Grail, rather it had become to me the symbol of all that was the Battle of Waterloo - the tragedy, the drama, the irony, the heartbreak and the heroics. I could have as easily fixated upon the site of the Duchess of Richmond's Ball, which would have been just as fitting, as that no longer exists, either.

So . . . what's next on my 19th century bucket list? The decoupage screen Beau Brummell was toiling away on and which was meant to be a present to his great good friend Frederica, Duchess of York. Brummell stopped working on it when news of her death reached him in France. Trouble is, I have no idea where to begin looking for it. If you're an aged aristocrat living in the back of beyond who happens to have the screen in your attic, email me. Heck, email me even if the screen only used to be in your attic. Victoria, Jo and I will then embark on what we shall no doubt call "The Quest for Brummell's Screen."

Victoria here, freshly off the plane from Heathrow and fighting a stubborn cold (you don't want to hear about it!), ready to prepare lots of material for the blog, including visits to the tomb of Sir John Moore in Spain, Walmer Castle, Trooping the Colour 2011, Strawberry Hill, and a lovely day in Windsor with Hester Davenport. And the Queen in her pink hat. However, I could not help but add to Kristine's search. And perhaps give an answer.

At Newstead Abbey, former home of the Lords Byron, and now open to tourists under the auspices of the town of Nottingham, there is a decoupage screen purportedly made by George, Lord B, himself. Perhaps this is the screen Kristine is looking for -- and if so, my dear, you have seen it already. Someplace among the piles of booklets and ephemera I have collected on my jaunts to England is a booklet which tells the story. Now to find it. Hopeless? Perhaps. Stay tuned.

Kristine's reply - Byron . . . feh. No, I'm looking for the Brummell screen. I don't remember any screen at Newstead Abbey. Methinks I was too creeped out by the place to notice much. What. A. Dump. Were decoupage screens a big fad for men at that time!? We'll have to look into it . . . can't wait to see your trip posts! Did you bring back any Wills and Kate tat for me? Did you pick up any issues of Country Life? I can't believe you were with Hester for Ascot again - two years in a row. That tears it, we'll just have to book another trip for next June and make it a triple play. Went online to see when the Wellington Conference is happening in 2013 but could find nothing. Already told Greg I'm going and asked if he wanted to come along. He gave me that look, the one where his eyes glaze over at the mention of anything Artie, so it's safe to say he won't be joining me/us in Southampton . . . . Uh, oh . . . sorry . . . forgot we were in public . . . . I'll email you the rest of my rant.

Victoria responds: You mean there are two Bs? Byron and Brummell are different guys? In my clogged brain (not to mention nasal passages), I see one well-dressed poet -- oh, no. Now I remember. The one who had his valet clean his boots with champagne (what a dreadful waste) and the one who was mad, bad and dangerous to know. So I take it all back. But it is curious about decoupaged screens and men, isn't it? Do you suppose they had classes at Eton or Cambridge? What ever happened to Queer Eye, anyway? I think I'll go back to bed. Sniff.

Kristine says - I was just thinking about Queer Eye For The Straight Guy last week! Whatever did happen to that show? I loved it. I love Carson. Did you see him on Oprah? She sent him to Bucklebury (sp?) Kate Middleton's hometown. What a hoot! I know you're still sick, but listen to me through the haze of illness . . . . Byron and Brummell are/were, indeed, two different people. And I still maintain that history recorded it incorrectly and that it was Byron who said the dangerous to know thing about that lunatic, Caro Lamb. Too bad they're separated by centuries . . . she and Lindsay Lohan would have been BFFs. [image error]

Published on June 18, 2011 23:01

A Visit to the Field of Waterloo

The Forest of Soignes From: The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Butler: Headmaster of Shrewsbury SchoolJuly 9th. 1816 —From Brussels through Waterloo to the field of battle, about fourteen miles, through the Forest of Soignies, almost all the way a most detestable pavi full of holes. Waterloo is a miserable village of about twenty houses; its small red brick church, designed in segments of ellipses, is about twenty-five or possibly thirty feet in diameter. Here are monumental inscriptions to the memory of many of our brave country men. In about half a mile from Waterloo we quit the Forest of Soignes, and the ground becomes an elevated plain with some moderate undulations. In about two miles more we come to a place where a bye-road crosses the principal road. Here is an elm of moderate size on the right-hand side of the road, some of whose branches have been torn off by cannon balls; this is the famous Wellington tree, where the Duke was posted during the greater part of the battle, and is somewhat nearer the left wing than the centre of the battle. Close to the cross-road opposite this runs La Haye Sainte, a broken stumpy hedge. Directly opposite this tree, on the road-side, lay the skeleton of an unburied horse, and near the tree itself I picked up a human rib. The whole field of battle is now covered with crops of wheat and rye, which grow with a rank and peculiar green over the graves of the slain and mark them readily. About one hundred and fifty yards below the Wellington tree, which itself stands on the top of Mount St. Jean, in the hollow, is the little farm of La Haye Sainte, where the dreadful slaughter of the German Legion took place; they defended the place till they had spent all their ammunition, and were then massacred to a man, but not till they had taken a bloody revenge. The house and walls, the barn doors and gates, are full of marks from cannon and musket balls. In the barn are innumerable shot holes, and the plaster is still covered with blood, and the holes which the bayonets made through their bodies into it are still to be seen.

The Forest of Soignes From: The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Butler: Headmaster of Shrewsbury SchoolJuly 9th. 1816 —From Brussels through Waterloo to the field of battle, about fourteen miles, through the Forest of Soignies, almost all the way a most detestable pavi full of holes. Waterloo is a miserable village of about twenty houses; its small red brick church, designed in segments of ellipses, is about twenty-five or possibly thirty feet in diameter. Here are monumental inscriptions to the memory of many of our brave country men. In about half a mile from Waterloo we quit the Forest of Soignes, and the ground becomes an elevated plain with some moderate undulations. In about two miles more we come to a place where a bye-road crosses the principal road. Here is an elm of moderate size on the right-hand side of the road, some of whose branches have been torn off by cannon balls; this is the famous Wellington tree, where the Duke was posted during the greater part of the battle, and is somewhat nearer the left wing than the centre of the battle. Close to the cross-road opposite this runs La Haye Sainte, a broken stumpy hedge. Directly opposite this tree, on the road-side, lay the skeleton of an unburied horse, and near the tree itself I picked up a human rib. The whole field of battle is now covered with crops of wheat and rye, which grow with a rank and peculiar green over the graves of the slain and mark them readily. About one hundred and fifty yards below the Wellington tree, which itself stands on the top of Mount St. Jean, in the hollow, is the little farm of La Haye Sainte, where the dreadful slaughter of the German Legion took place; they defended the place till they had spent all their ammunition, and were then massacred to a man, but not till they had taken a bloody revenge. The house and walls, the barn doors and gates, are full of marks from cannon and musket balls. In the barn are innumerable shot holes, and the plaster is still covered with blood, and the holes which the bayonets made through their bodies into it are still to be seen.

La Haye Sainte

La Haye Sainte

"In a hollow near this scene of carnage lie the bodies of two thousand French Cuirassiers in one grave, and about twenty yards farther is the spot to which Bonaparte advanced to cheer the Imperial Guard for their last charge; it is scarcely possible but that he must have exposed himself greatly in so doing. The little valley between the undulation of Mount St. Jean, where the British were posted, and that of La Belle Alliance, which was occupied by the French, is not more than about a quarter of a mile across; the Duke of Wellington and Bonaparte, whose general station was on this hill, cannot have been more than that distance, or a very little more, from each other. On going to the station of Bonaparte we had a fine view of the whole field, and, though quite ignorant of military affairs, could not but see the superiority of the British position. The undulation on their side being a little more abrupt than that of the French, they were themselves protected in some measure, and their force considerably concealed, while that of the French was perfectly distinguishable. The right wing of the British was at Hougoumont [rather Goumont], a chateau of great importance and of very considerable strength. Their left wing was at the end of La Haye, about a short half-mile or less from the farm of St. Jean, which was almost of the same importance for its protection as Hougoumont for that of the right. The whole line could not extend more than a mile and a quarter. The French were posted on the opposite eminence, and here in this small space three hundred cannon, independent of all other weapons, were doing the work of death all day. Our guide, a very intelligent peasant, told us that the whole ground was literally covered with carcasses, and that about five days after the stench began to be so horrid that it was hardly possible to bury them on the left of the British, and of course on the right of the French position. At less than a mile and a half is the wood from which the Prussians made their appearance. La Belle Alliance is about half a mile or a little less from Mount St. Jean; here we turned off to see the chateau of Hougoumont, which was most important to secure the British right and French left wing, and was therefore eagerly contested; four thousand British were posted here, and withstood with only the bayonet and musketry all the attacks of an immense body of French with cannon. The French were posted in a wood, now a good deal cut down, close to the wall of the garden at Hougoumont. The British had made holes in the wall tofire through, and the French aimed at these holes. The whole wall is so battered by bullets that it looks as if thousands of pickaxes had been employed to pick the bricks. The trees are torn by cannon balls, and some not above eight inches in diameter, being half shot away on one side, still flourish.

Hougoumont

Hougoumont

"Passing round the garden wall to the gates, the scene of devastation is yet more striking. The front gates communicate with the chateau, a plain gentleman's house, the back ones (which are directly opposite) with the farmer's residence. This was occupied three times by the French, who were thrice repulsed; but the English were never driven from the chateau. The tower, or rather dovecote, of the chateau was burnt down, but a chapel near it, about twenty feet long, was preserved in the midst of the fire; the flames had caught the crucifix and had burnt one foot of the image, and then went out. This was of course considered a great miracle. From the chapel we went into the garden. Its repose and gaiety of flowers, together with the neatness of its cultivation, formed a striking contrast with the ruined mansion, the blackened, torn, and in some parts blood-stained walls, and the charred timbers about it. In a corner of this garden is the spot where Captain Crawford and eight men were killed by one cannon ball, which entered opposite them by a hole still there and went through the house and lodged in another wall; I have seen the ball in the Waterloo Museum.

The Waterloo Musuem, Wellington's former headquarters

The Waterloo Musuem, Wellington's former headquarters

Going along the green alleys of the garden, quite overarched with hornbeam, we see the different holes broken by the English to fire on their enemies, and a gap on the northeast angle of the garden is the gap made by the French, who attempted to enter there, but were repulsed. Had they gained entrance the slaughter would have been dreadful, as we had four thousand men in the garden, which from its thick hedges has many strongholds, and they were greatly more numerous. The English also lined a strong hedge opposite the wood in which the French were, which they could not force, but the trees are terribly torn by cannon. The loss of Hougoumont would probably have been fatal to us. From the gap above mentioned, looking up to the line of the British on Mount St. Jean, is one small bush; here Major Howard was killed.

La Belle Alliance

La Belle Alliance

"Leaving Hougoumont, we returned to La Belle Alliance, where we once more reviewed the field of battle, and found some bullets and fragments of accoutrements among the ploughed soil. The crop is not so thriving on the French side, but it was still more richly watered with blood; in fact the soil, which on the British position is rather a light sand, is here a stiffish clay. From La Belle Alliance we proceeded to Genappe, another post, passing by a burnt house called la maison du roi; here Napoleon slept on the eventful eve of the battle. Following the course of the French in their retreat, we proceeded to another post, to Quatre Bras. Here was the famous [stand ?] made by the Highlanders against the whole French Army on the 16th. It is a field a little to the left at the turning to Namur. Hence we proceeded, having Fleurus on our right, to Sombreffe, where was the severe battle of the Prussians on the 16th, and thence to Namur, where the French continued their retreat.

The tourqoise circle upper right marks Genappe

The tourqoise circle upper right marks Genappe

"At Genappe, which is a straggling village, with narrow streets, dreadful slaughter was made by the Prussians on the night of the 16th; here Bonaparte's carriage was taken, and he narrowly escaped himself. From hence to Namur the road was strewed with dead, the Prussians having killed, it is thought, not less than twenty thousand in the pursuit. Nothing can be more detestable than the paved roads, more miserable than the villages, or more uninteresting in the natural appearance of the country than the whole course from Brussels to Namur, about forty-seven miles, the scene of all these great historical events in the present and past ages."[image error]

The Forest of Soignes From: The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Butler: Headmaster of Shrewsbury SchoolJuly 9th. 1816 —From Brussels through Waterloo to the field of battle, about fourteen miles, through the Forest of Soignies, almost all the way a most detestable pavi full of holes. Waterloo is a miserable village of about twenty houses; its small red brick church, designed in segments of ellipses, is about twenty-five or possibly thirty feet in diameter. Here are monumental inscriptions to the memory of many of our brave country men. In about half a mile from Waterloo we quit the Forest of Soignes, and the ground becomes an elevated plain with some moderate undulations. In about two miles more we come to a place where a bye-road crosses the principal road. Here is an elm of moderate size on the right-hand side of the road, some of whose branches have been torn off by cannon balls; this is the famous Wellington tree, where the Duke was posted during the greater part of the battle, and is somewhat nearer the left wing than the centre of the battle. Close to the cross-road opposite this runs La Haye Sainte, a broken stumpy hedge. Directly opposite this tree, on the road-side, lay the skeleton of an unburied horse, and near the tree itself I picked up a human rib. The whole field of battle is now covered with crops of wheat and rye, which grow with a rank and peculiar green over the graves of the slain and mark them readily. About one hundred and fifty yards below the Wellington tree, which itself stands on the top of Mount St. Jean, in the hollow, is the little farm of La Haye Sainte, where the dreadful slaughter of the German Legion took place; they defended the place till they had spent all their ammunition, and were then massacred to a man, but not till they had taken a bloody revenge. The house and walls, the barn doors and gates, are full of marks from cannon and musket balls. In the barn are innumerable shot holes, and the plaster is still covered with blood, and the holes which the bayonets made through their bodies into it are still to be seen.

The Forest of Soignes From: The Life and Letters of Dr. Samuel Butler: Headmaster of Shrewsbury SchoolJuly 9th. 1816 —From Brussels through Waterloo to the field of battle, about fourteen miles, through the Forest of Soignies, almost all the way a most detestable pavi full of holes. Waterloo is a miserable village of about twenty houses; its small red brick church, designed in segments of ellipses, is about twenty-five or possibly thirty feet in diameter. Here are monumental inscriptions to the memory of many of our brave country men. In about half a mile from Waterloo we quit the Forest of Soignes, and the ground becomes an elevated plain with some moderate undulations. In about two miles more we come to a place where a bye-road crosses the principal road. Here is an elm of moderate size on the right-hand side of the road, some of whose branches have been torn off by cannon balls; this is the famous Wellington tree, where the Duke was posted during the greater part of the battle, and is somewhat nearer the left wing than the centre of the battle. Close to the cross-road opposite this runs La Haye Sainte, a broken stumpy hedge. Directly opposite this tree, on the road-side, lay the skeleton of an unburied horse, and near the tree itself I picked up a human rib. The whole field of battle is now covered with crops of wheat and rye, which grow with a rank and peculiar green over the graves of the slain and mark them readily. About one hundred and fifty yards below the Wellington tree, which itself stands on the top of Mount St. Jean, in the hollow, is the little farm of La Haye Sainte, where the dreadful slaughter of the German Legion took place; they defended the place till they had spent all their ammunition, and were then massacred to a man, but not till they had taken a bloody revenge. The house and walls, the barn doors and gates, are full of marks from cannon and musket balls. In the barn are innumerable shot holes, and the plaster is still covered with blood, and the holes which the bayonets made through their bodies into it are still to be seen.

La Haye Sainte

La Haye Sainte"In a hollow near this scene of carnage lie the bodies of two thousand French Cuirassiers in one grave, and about twenty yards farther is the spot to which Bonaparte advanced to cheer the Imperial Guard for their last charge; it is scarcely possible but that he must have exposed himself greatly in so doing. The little valley between the undulation of Mount St. Jean, where the British were posted, and that of La Belle Alliance, which was occupied by the French, is not more than about a quarter of a mile across; the Duke of Wellington and Bonaparte, whose general station was on this hill, cannot have been more than that distance, or a very little more, from each other. On going to the station of Bonaparte we had a fine view of the whole field, and, though quite ignorant of military affairs, could not but see the superiority of the British position. The undulation on their side being a little more abrupt than that of the French, they were themselves protected in some measure, and their force considerably concealed, while that of the French was perfectly distinguishable. The right wing of the British was at Hougoumont [rather Goumont], a chateau of great importance and of very considerable strength. Their left wing was at the end of La Haye, about a short half-mile or less from the farm of St. Jean, which was almost of the same importance for its protection as Hougoumont for that of the right. The whole line could not extend more than a mile and a quarter. The French were posted on the opposite eminence, and here in this small space three hundred cannon, independent of all other weapons, were doing the work of death all day. Our guide, a very intelligent peasant, told us that the whole ground was literally covered with carcasses, and that about five days after the stench began to be so horrid that it was hardly possible to bury them on the left of the British, and of course on the right of the French position. At less than a mile and a half is the wood from which the Prussians made their appearance. La Belle Alliance is about half a mile or a little less from Mount St. Jean; here we turned off to see the chateau of Hougoumont, which was most important to secure the British right and French left wing, and was therefore eagerly contested; four thousand British were posted here, and withstood with only the bayonet and musketry all the attacks of an immense body of French with cannon. The French were posted in a wood, now a good deal cut down, close to the wall of the garden at Hougoumont. The British had made holes in the wall tofire through, and the French aimed at these holes. The whole wall is so battered by bullets that it looks as if thousands of pickaxes had been employed to pick the bricks. The trees are torn by cannon balls, and some not above eight inches in diameter, being half shot away on one side, still flourish.

Hougoumont

Hougoumont "Passing round the garden wall to the gates, the scene of devastation is yet more striking. The front gates communicate with the chateau, a plain gentleman's house, the back ones (which are directly opposite) with the farmer's residence. This was occupied three times by the French, who were thrice repulsed; but the English were never driven from the chateau. The tower, or rather dovecote, of the chateau was burnt down, but a chapel near it, about twenty feet long, was preserved in the midst of the fire; the flames had caught the crucifix and had burnt one foot of the image, and then went out. This was of course considered a great miracle. From the chapel we went into the garden. Its repose and gaiety of flowers, together with the neatness of its cultivation, formed a striking contrast with the ruined mansion, the blackened, torn, and in some parts blood-stained walls, and the charred timbers about it. In a corner of this garden is the spot where Captain Crawford and eight men were killed by one cannon ball, which entered opposite them by a hole still there and went through the house and lodged in another wall; I have seen the ball in the Waterloo Museum.

The Waterloo Musuem, Wellington's former headquarters

The Waterloo Musuem, Wellington's former headquartersGoing along the green alleys of the garden, quite overarched with hornbeam, we see the different holes broken by the English to fire on their enemies, and a gap on the northeast angle of the garden is the gap made by the French, who attempted to enter there, but were repulsed. Had they gained entrance the slaughter would have been dreadful, as we had four thousand men in the garden, which from its thick hedges has many strongholds, and they were greatly more numerous. The English also lined a strong hedge opposite the wood in which the French were, which they could not force, but the trees are terribly torn by cannon. The loss of Hougoumont would probably have been fatal to us. From the gap above mentioned, looking up to the line of the British on Mount St. Jean, is one small bush; here Major Howard was killed.

La Belle Alliance

La Belle Alliance"Leaving Hougoumont, we returned to La Belle Alliance, where we once more reviewed the field of battle, and found some bullets and fragments of accoutrements among the ploughed soil. The crop is not so thriving on the French side, but it was still more richly watered with blood; in fact the soil, which on the British position is rather a light sand, is here a stiffish clay. From La Belle Alliance we proceeded to Genappe, another post, passing by a burnt house called la maison du roi; here Napoleon slept on the eventful eve of the battle. Following the course of the French in their retreat, we proceeded to another post, to Quatre Bras. Here was the famous [stand ?] made by the Highlanders against the whole French Army on the 16th. It is a field a little to the left at the turning to Namur. Hence we proceeded, having Fleurus on our right, to Sombreffe, where was the severe battle of the Prussians on the 16th, and thence to Namur, where the French continued their retreat.

The tourqoise circle upper right marks Genappe

The tourqoise circle upper right marks Genappe"At Genappe, which is a straggling village, with narrow streets, dreadful slaughter was made by the Prussians on the night of the 16th; here Bonaparte's carriage was taken, and he narrowly escaped himself. From hence to Namur the road was strewed with dead, the Prussians having killed, it is thought, not less than twenty thousand in the pursuit. Nothing can be more detestable than the paved roads, more miserable than the villages, or more uninteresting in the natural appearance of the country than the whole course from Brussels to Namur, about forty-seven miles, the scene of all these great historical events in the present and past ages."[image error]

Published on June 18, 2011 00:08

June 17, 2011

Meet Alan Cumming, Host of Masterpiece Mystery!

This coming Sunday, Masterpiece Mystery will debut the first of three new Hercule Poirot espisodes featuring David Suchet as the suave Belgian detective. In the first, Three Act Tragedy, a cocktail party is the scene of a crime. This programming note reminded me of my interest in the Mystery host, Alan Cumming. As I began watching him as the new host of Masterpiece Mystery! last season, I became intrigued by the Scotsman, whose attraction owes much to the fact that he seems such a Cheeky Monkey.

Born on January 27, 1965, in Aberfeldy, Scotland, Cumming is an actor -Mr. Elton in the 1996 film version of Emma, X2: X-Men United, Goldeneye, Eyes Wide Shut and Spy Kids, while on Broadway he's appeared as Mac the Knife in The Threepenny Opera, and as the Emcee in Cabaret, for which he won the Tony in 1998. Cumming is also an author, Tommy's Tale, and once fragrance mogul with his scent, Cumming. Cheeky Monkey

Born on January 27, 1965, in Aberfeldy, Scotland, Cumming is an actor -Mr. Elton in the 1996 film version of Emma, X2: X-Men United, Goldeneye, Eyes Wide Shut and Spy Kids, while on Broadway he's appeared as Mac the Knife in The Threepenny Opera, and as the Emcee in Cabaret, for which he won the Tony in 1998. Cumming is also an author, Tommy's Tale, and once fragrance mogul with his scent, Cumming. Cheeky Monkey

As well as playing host on Masterpiece Mystery! Cumming also plays Eli Gold on the CBS television show The Good Wife, a character who became a series regular this season. Additionally, he recently took up the role of a drag queen in a t.v. drama. His character, Desrae in Sky1's The Runaway, is unusual not only because he is a transvestite but also because with his Italian gangster boyfriend Joey (Ken Stott) and the runaway murderess Cathy (Joanna Vanderham) they take in, the threesome are the most law-abiding, functional family unit in the piece.

Cumming has also written articles for magazines, notably as a contributing editor for Marie Claire magazine, writing on the haute couture shows in Paris. Additionally, Cumming recorded a duet of "Baby, It's Cold Outside" with Liza Minnelli to raise money for Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS and the September 11 Fund.

In 2005 he released a fragance called "Cumming," and a related line of scented bath lotion and body wash sold exclusively at Sephora until the partnership was dissolved due to a distribution agreement. Cumming lives in New York City with his husband (via UK civil union), graphic artist Grant Shaffer, and their dogs, Honey and Leon. The couple dated for two years before entering into a civil partnership at the Old Royal Naval College Greenwich on January 7, 2007. One can only wonder what ghosts in the hallowed halls of the Naval College thought of that progressive move.

In 2005 he released a fragance called "Cumming," and a related line of scented bath lotion and body wash sold exclusively at Sephora until the partnership was dissolved due to a distribution agreement. Cumming lives in New York City with his husband (via UK civil union), graphic artist Grant Shaffer, and their dogs, Honey and Leon. The couple dated for two years before entering into a civil partnership at the Old Royal Naval College Greenwich on January 7, 2007. One can only wonder what ghosts in the hallowed halls of the Naval College thought of that progressive move.

Cumming was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2009 Queen's Birthday Honours List for services to film, theatre and the arts and activism for LGBT rights. On November 7, 2008, Cumming became a dual-national and was sworn in as a citizen of the United States of America at a ceremony in New York City.

Cumming was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2009 Queen's Birthday Honours List for services to film, theatre and the arts and activism for LGBT rights. On November 7, 2008, Cumming became a dual-national and was sworn in as a citizen of the United States of America at a ceremony in New York City.

Cumming was recently wow-ing them in Alan Cumming: UNCUT at the Santa Monica College Performing Arts Center. BroadwayWorld.com says, "The show is a comedic and topical evening of provocative monologues and music and offers an eclectic range of witty, biting compositions, from songs by Sondheim, Bacharach, and Kander to a selection from Hedwig and The Angry Inch. It's not only the music but what Cumming has to say that makes the evening so hilarious and haunting. He played to sell-out audiences and rave reviews in New York at Feinstein's at Loews Regency with a one-man cabaret show based on his recently released his debut album, I Bought a Blue Car Today, Stephen Holden of The New York Times says 'Taking command of the stage with the ease of a vaudevillian who has been treading the boards for decades, Mr. Cumming entertained with a capital E.'"

I knew he was a Cheeky Monkey.

Alan will take you on a behind-the-scenes video tour of the Masterpiece Mystery! set if you click here. [image error]

Born on January 27, 1965, in Aberfeldy, Scotland, Cumming is an actor -Mr. Elton in the 1996 film version of Emma, X2: X-Men United, Goldeneye, Eyes Wide Shut and Spy Kids, while on Broadway he's appeared as Mac the Knife in The Threepenny Opera, and as the Emcee in Cabaret, for which he won the Tony in 1998. Cumming is also an author, Tommy's Tale, and once fragrance mogul with his scent, Cumming. Cheeky Monkey

Born on January 27, 1965, in Aberfeldy, Scotland, Cumming is an actor -Mr. Elton in the 1996 film version of Emma, X2: X-Men United, Goldeneye, Eyes Wide Shut and Spy Kids, while on Broadway he's appeared as Mac the Knife in The Threepenny Opera, and as the Emcee in Cabaret, for which he won the Tony in 1998. Cumming is also an author, Tommy's Tale, and once fragrance mogul with his scent, Cumming. Cheeky MonkeyAs well as playing host on Masterpiece Mystery! Cumming also plays Eli Gold on the CBS television show The Good Wife, a character who became a series regular this season. Additionally, he recently took up the role of a drag queen in a t.v. drama. His character, Desrae in Sky1's The Runaway, is unusual not only because he is a transvestite but also because with his Italian gangster boyfriend Joey (Ken Stott) and the runaway murderess Cathy (Joanna Vanderham) they take in, the threesome are the most law-abiding, functional family unit in the piece.

Cumming has also written articles for magazines, notably as a contributing editor for Marie Claire magazine, writing on the haute couture shows in Paris. Additionally, Cumming recorded a duet of "Baby, It's Cold Outside" with Liza Minnelli to raise money for Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS and the September 11 Fund.

In 2005 he released a fragance called "Cumming," and a related line of scented bath lotion and body wash sold exclusively at Sephora until the partnership was dissolved due to a distribution agreement. Cumming lives in New York City with his husband (via UK civil union), graphic artist Grant Shaffer, and their dogs, Honey and Leon. The couple dated for two years before entering into a civil partnership at the Old Royal Naval College Greenwich on January 7, 2007. One can only wonder what ghosts in the hallowed halls of the Naval College thought of that progressive move.

In 2005 he released a fragance called "Cumming," and a related line of scented bath lotion and body wash sold exclusively at Sephora until the partnership was dissolved due to a distribution agreement. Cumming lives in New York City with his husband (via UK civil union), graphic artist Grant Shaffer, and their dogs, Honey and Leon. The couple dated for two years before entering into a civil partnership at the Old Royal Naval College Greenwich on January 7, 2007. One can only wonder what ghosts in the hallowed halls of the Naval College thought of that progressive move.  Cumming was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2009 Queen's Birthday Honours List for services to film, theatre and the arts and activism for LGBT rights. On November 7, 2008, Cumming became a dual-national and was sworn in as a citizen of the United States of America at a ceremony in New York City.

Cumming was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2009 Queen's Birthday Honours List for services to film, theatre and the arts and activism for LGBT rights. On November 7, 2008, Cumming became a dual-national and was sworn in as a citizen of the United States of America at a ceremony in New York City.Cumming was recently wow-ing them in Alan Cumming: UNCUT at the Santa Monica College Performing Arts Center. BroadwayWorld.com says, "The show is a comedic and topical evening of provocative monologues and music and offers an eclectic range of witty, biting compositions, from songs by Sondheim, Bacharach, and Kander to a selection from Hedwig and The Angry Inch. It's not only the music but what Cumming has to say that makes the evening so hilarious and haunting. He played to sell-out audiences and rave reviews in New York at Feinstein's at Loews Regency with a one-man cabaret show based on his recently released his debut album, I Bought a Blue Car Today, Stephen Holden of The New York Times says 'Taking command of the stage with the ease of a vaudevillian who has been treading the boards for decades, Mr. Cumming entertained with a capital E.'"

I knew he was a Cheeky Monkey.

Alan will take you on a behind-the-scenes video tour of the Masterpiece Mystery! set if you click here. [image error]

Published on June 17, 2011 00:12

June 16, 2011

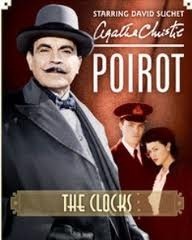

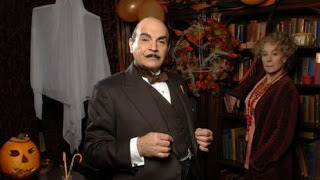

Hercule Poirot Returns to Masterpiece Mystery!

Actor Martin Shaw as Cartwright and Suchet as Poirot

Actor Martin Shaw as Cartwright and Suchet as Poirot

This Sunday, David Suchet returns as Hercule Poirot in the first of a trio of new (to the US) episodes, Three Act Tragedy, in which Poirot is one of 13 guests who attend a party at the great actor Sir Charles Cartwright's Cornish mansion. A local reverend dies while drinking a cocktail, but no poison is found in his glass. Poirot and Cartwright decide to investigate when another victim dies in the same manner.

In The Clocks, airing on June 26, multiple frozen clocks factor into a murder. Sheila Webb, a typist for-hire, arrives at her afternoon appointment to find a well-dressed corpse surrounded by six clocks, four of which are stopped at 4:13. Lieutenant Colin Race (Tom Burke) is investigating the death of two Navy personnel when a distraught Sheila Webb (Jaime Winstone) runs out of 19 Wilbraham Crescent and into his arms. Poirot (David Suchet) arrives in Dover to help Colin determine if Sheila is responsible for the murder of the middle-aged man found stabbed on the sitting room floor.

Poirot investigates a death at a festive event turned foul in Hallowe'en Party, airing on July 3. Ariadne Oliver attends a children's Hallowe'en party and hears a young girl boasting that she has witnessed a murder. Later that evening, the child is found dead, drowned in a bucket. Ariadne sends for Poirot, who takes the young victim's story seriously and finds there have been several other suspicious deaths in the village. When another child is found drowned, Poirot realizes that a third is in danger.

Suchet has been playing Poirot perfectly for twenty years now, beginning 1989 with The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. Suchet explained how he gets into character in an interview given to The Guardian, saying that he can't eat much on the days he is Poirot "because that padding is not the most comfortable, especially in the summer", so he has a bowl of fruit and heads into makeup. "And then as I'm being made up I'm thinking about the day," he says. "And I'm watching, very closely, the face change. And it does change, very subtly. My makeup artist and I work very closely together, so every detail is done and the hair is all put back. And then the touchstone, absolutely the pivotal point - the moustache - goes on. And as soon as my lip feels that moustache, two things happen - first of all, I know he's there, but it also gives my top lip a very, very slight restraint. So I can't smile like that," he grins broadly, "I can only smile like that," he gives a tight half-smile. "And 20 years of that, I don't know what it is, but psychologically it enables me to come back to him. And from then on, until lunch, I'm him . . . "

With these three espisodes in the can, there are only six of Christie's Poirot stories left to film and Suchy hopes to be on board. Speaking about Poirot, Suchy told The Guardian, "I'm not bored, not bored at all. He's irritating, but he's wonderful as well, and he's so interesting to be. And I'm going to eat them up."

As will we. [image error]

Actor Martin Shaw as Cartwright and Suchet as Poirot

Actor Martin Shaw as Cartwright and Suchet as PoirotThis Sunday, David Suchet returns as Hercule Poirot in the first of a trio of new (to the US) episodes, Three Act Tragedy, in which Poirot is one of 13 guests who attend a party at the great actor Sir Charles Cartwright's Cornish mansion. A local reverend dies while drinking a cocktail, but no poison is found in his glass. Poirot and Cartwright decide to investigate when another victim dies in the same manner.

In The Clocks, airing on June 26, multiple frozen clocks factor into a murder. Sheila Webb, a typist for-hire, arrives at her afternoon appointment to find a well-dressed corpse surrounded by six clocks, four of which are stopped at 4:13. Lieutenant Colin Race (Tom Burke) is investigating the death of two Navy personnel when a distraught Sheila Webb (Jaime Winstone) runs out of 19 Wilbraham Crescent and into his arms. Poirot (David Suchet) arrives in Dover to help Colin determine if Sheila is responsible for the murder of the middle-aged man found stabbed on the sitting room floor.

Poirot investigates a death at a festive event turned foul in Hallowe'en Party, airing on July 3. Ariadne Oliver attends a children's Hallowe'en party and hears a young girl boasting that she has witnessed a murder. Later that evening, the child is found dead, drowned in a bucket. Ariadne sends for Poirot, who takes the young victim's story seriously and finds there have been several other suspicious deaths in the village. When another child is found drowned, Poirot realizes that a third is in danger.

Suchet has been playing Poirot perfectly for twenty years now, beginning 1989 with The Adventure of the Clapham Cook. Suchet explained how he gets into character in an interview given to The Guardian, saying that he can't eat much on the days he is Poirot "because that padding is not the most comfortable, especially in the summer", so he has a bowl of fruit and heads into makeup. "And then as I'm being made up I'm thinking about the day," he says. "And I'm watching, very closely, the face change. And it does change, very subtly. My makeup artist and I work very closely together, so every detail is done and the hair is all put back. And then the touchstone, absolutely the pivotal point - the moustache - goes on. And as soon as my lip feels that moustache, two things happen - first of all, I know he's there, but it also gives my top lip a very, very slight restraint. So I can't smile like that," he grins broadly, "I can only smile like that," he gives a tight half-smile. "And 20 years of that, I don't know what it is, but psychologically it enables me to come back to him. And from then on, until lunch, I'm him . . . "

With these three espisodes in the can, there are only six of Christie's Poirot stories left to film and Suchy hopes to be on board. Speaking about Poirot, Suchy told The Guardian, "I'm not bored, not bored at all. He's irritating, but he's wonderful as well, and he's so interesting to be. And I'm going to eat them up."

As will we. [image error]

Published on June 16, 2011 00:36

June 15, 2011

Sir Walter Scott at Waterloo

Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter ScottFrom Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott by John Gibson Lockhart (1838)

I found the letter in question preserved among Scott's papers, I perused it with a peculiar interest; and I now venture, with the writer's permission, to present it to the reader. It was addressed by Sir Charles Bell to his brother, an eminent barrister in Edinburgh, who transmitted it to Scott. "When I read it," said he, "it set me on fire." The marriage of Miss Maclean Clephane of Torloisk with the Earl of Compton (now Marquis of Northampton), which took place on the 24th of July, was in fact the only cause why he did not leave Scotland instantly; for that dear young friend had chosen Scott for her guardian, and on him accordingly devolved the chief care of the arrangements on this occasion. The extract sent to him by Mr George Joseph Bell is as follows:—

"Brussels, 2d July, 1815.

"This country, the finest in the world, has been of late quite out of our minds. I did not, in any degree, anticipate the pleasure I should enjoy, the admiration forced from me, on coming into one of these antique towns, or in journeying through this rich garden. Can you recollect the time when there were gentlemen meeting at the Cross of Edinburgh, or those whom we thought such? They are all collected here. You see the very men, with their scraggy necks sticking out of the collars of their old-fashioned square-skirted coats— their canes—their cocked-hats; and, when they meet, the formal bow, the hat off to the ground, and the powder flying in the wind. I could divert you with the odd resemblances of the Scottish faces among- the peasants, too—but I noted them at the time- with my pencil, and I write to you only of things that you won't find in my pocket-book.

"I have just returned from seeing the French wounded received in their hospital; and could you see them laid out naked, or almost so—100 in a row of low beds on the ground—though wounded, exhausted, beaten, you would still conclude with me that these were men capable of marching unopposed from the west of Europe to the east of Asia. Strong, thickset, hardy veterans, brave spirits and unsubdued, as they cast their wild glance upon you,—their black eyes and brown cheeks finely contrasted with the fresh sheets,—you would much admire their capacity of adaptation. These fellows are brought from the field after lying many days on the ground; many dying—many in the agony—many miserably racked with pain and spasms; and the next mimicks his fellow, and gives it a tune,—Aha, vous chantez bien! How they are wounded you will see in my notes. But I must not have you to lose the present impression on me of the formidable nature of these fellows as exemplars of the breed in France. It is a forced praise; for from all I have seen, and all I have heard of their fierceness, cruelty, and bloodthirstiness, I cannot convey to you my detestation of this race of trained banditti. By what means they are to be kept in subjection until other habits come upon them, I know not; but I am convinced that these men cannot be left to the bent of their propensities.

"This superb city is now ornamented with the finest groupes of armed men that the most romantic fancy could dream of. I was struck with the words of a friend —E.: 'I saw,' said he, 'that man returning from the field on the 16th.'—(This was a Brunswicker of the Black or Death Hussars.)—' He was wounded, and had had his arm amputated on the field. He was among the first that came in. He rode straight and stark upon his horse—the bloody clouts about his stump—pale as death, but upright, with a stern, fixed expression of feature, as if loth to lose his revenge.' These troops are very remarkable in their fine military appearance; their dark and ominous dress sets off to advantage their strong, manly, northern features and white mustachios; and there is something more than commonly impressive about the whole effect.

"This is the second Sunday after the battle, and many are not yet dressed. There are 20,000 wounded in this town, besides those in the hospitals, and the many in the other towns ;—only 3000 prisoners; 80,000, they say, killed and wounded on both sides."

I think it not wonderful that this extract should have set Scott's imagination effectually on fire; that he should have grasped at the idea of seeing probably the last shadows of real warfare that his own age would afford; or that some parts of the great surgeon's simple phraseology are reproduced, almost verbatim, in the first of "Paul's Letters to his Kinsfolk."

. . . . . At Brussels, Scott found the small English garrison left there in command of Major-General Sir Frederick Adam, the son of his highly valued friend, the present Lord Chief Commissioner of the Jury Court in Scotland. Sir Frederick had been wounded at Waterloo, and could not as yet mount on horseback ; but one of his aides-de-camp, Captain Campbell, escorted Seott and his party to the field of battle, on which occasion they were also accompanied by another old acquaintance of his, Major Pryse Gordon, who being then on halfpay, happened to be domesticated with his family at Brussels. Major Gordon has since published two lively volumes of " Personal Memoirs;" and Gala bears witness to the fidelity of certain reminiscences of Scott at Brussels and Waterloo, which occupy one of the chapters of this work. I shall, therefore, extract the passage.

Louis-Victor Baillot, last French veteran of Waterloo"Sir Walter Scott accepted my services to conduct him to Waterloo: the General's aide-de-camp was also of the party. He made no secret of his having undertaken to write something on the battle; and perhaps he took the greater interest on this account in every thing that he saw. Besides, he had never seen the field of such a conflict; and never having been before on the Continent, it was all new to his comprehensive mind. The day was beautiful; and I had the precaution to send out a couple of saddle-horses, that he might not be fatigued in walking over the fields, which had been recently ploughed up. In our rounds we fell in with Monsieur de Costar, with whom he got into conversation. This man had attracted so much notice by his pretended story of being about the person of Napoleon, that he was of too much importance to be passed by: I did not, indeed, know as much of this fellow's charlatanism at that time as afterwards, when I saw him confronted with a blacksmith of La Belle Alliance, who had been his companion in a hiding-place ten miles from the field during the whole day; a fact which he could not deny. But he had got up a tale so plausible and so profitable, that he could afford to bestow hush-money on the companion of his flight, so that the imposition was but little known; and strangers continued to be gulled. He had picked up a good deal of information about the positions and details of the battle; and being naturally a sagacious Wallon, and speaking French pretty fluently, he became the favourite cicerone, and every lie he told was taken for gospel. Year after year, until his death in 1824, he continued his popularity, and raised the price of his rounds from a couple of francs to five; besides as much for the hire of a horse, his own property; for he pretended that the fatigue of walking so many hours was beyond his powers. It has been said that in this way he realized every summer a couple of hundred Napoleons.

Louis-Victor Baillot, last French veteran of Waterloo"Sir Walter Scott accepted my services to conduct him to Waterloo: the General's aide-de-camp was also of the party. He made no secret of his having undertaken to write something on the battle; and perhaps he took the greater interest on this account in every thing that he saw. Besides, he had never seen the field of such a conflict; and never having been before on the Continent, it was all new to his comprehensive mind. The day was beautiful; and I had the precaution to send out a couple of saddle-horses, that he might not be fatigued in walking over the fields, which had been recently ploughed up. In our rounds we fell in with Monsieur de Costar, with whom he got into conversation. This man had attracted so much notice by his pretended story of being about the person of Napoleon, that he was of too much importance to be passed by: I did not, indeed, know as much of this fellow's charlatanism at that time as afterwards, when I saw him confronted with a blacksmith of La Belle Alliance, who had been his companion in a hiding-place ten miles from the field during the whole day; a fact which he could not deny. But he had got up a tale so plausible and so profitable, that he could afford to bestow hush-money on the companion of his flight, so that the imposition was but little known; and strangers continued to be gulled. He had picked up a good deal of information about the positions and details of the battle; and being naturally a sagacious Wallon, and speaking French pretty fluently, he became the favourite cicerone, and every lie he told was taken for gospel. Year after year, until his death in 1824, he continued his popularity, and raised the price of his rounds from a couple of francs to five; besides as much for the hire of a horse, his own property; for he pretended that the fatigue of walking so many hours was beyond his powers. It has been said that in this way he realized every summer a couple of hundred Napoleons."When Sir Walter had examined every point of defence and attack, we adjourned to the 'Original Duke of Wellington' at Waterloo, to lunch after the fatigues of the ride. Here he had a crowded levee of peasants, and collected a great many trophies, from cuirasses down to buttons and bullets. He picked up himself many little relics, and was fortunate in purchasing a grand cross of the legion of honour. But the most precious memorial was presented to him by my wife—a French soldier's book, well stained with blood, and containing some songs popular in the French army, which he found so interesting that he introduced versions of them in his 'Paul's Letters;' of which he did me the honour to send me a copy, with a letter, saying, 'that he considered my wife's gift as the most valuable of all his Waterloo relics.'[image error]

Published on June 15, 2011 00:39

June 14, 2011

Waterloo Teeth

Perhaps the most famous set of false teeth are the ivory set once worn by George Washington, pictured at left. Ivory dentures were popular into the 18th century, and were made from natural materials including walrus, elephant or hippopotamus ivory. These ill fitting and uncomfortable ivory dentures were replaced by porcelain dentures, introduced in the 1790's, which weren't much more successful due to their brightness and tendency to crack. In fact, the most favored material for false teeth was . . . . real teeth.

Perhaps the most famous set of false teeth are the ivory set once worn by George Washington, pictured at left. Ivory dentures were popular into the 18th century, and were made from natural materials including walrus, elephant or hippopotamus ivory. These ill fitting and uncomfortable ivory dentures were replaced by porcelain dentures, introduced in the 1790's, which weren't much more successful due to their brightness and tendency to crack. In fact, the most favored material for false teeth was . . . . real teeth. Presiding at the annual meeting of the British Dental Association held in Dublin in 1888, Mr. Daniel Corbett, Dental Surgeon, stated : "Six weeks was the usual time spent in the manufacture of a complete denture when working bone and natural teeth. When human teeth were in fashion, our supply was usually had from the graveyard, and I recollect what attention was paid to the gravedigger at his periodical visits to my father's residence with his gleanings from the coffins he chanced to expose in the discharge of his avocation. His visits were generally at night, and no hospitable duty in which my father might chance to be engaged was permitted to interfere with the reception of this ever welcome visitor into the sanctum sanctorum of the house.The gravediggers every Monday morning made their way to the dental depots, each with his sack on his back containing the ghastly burdens collected during the previous week . . . we can scarcely realize the horror of the scene of these men bringing the jaws which they had turned up in "God's acre" in their daily avocation; but mankind required teeth, and to meet the need most of those put in the mouth came from the jaws of the dead."

While graveyards were a profitable source for cadever teeth, the quantity of teeth typically on hand was limited. Enter the Peninsular Wars and the Battle of Waterloo. Of the 50,000 men who fell at the Battle of Waterloo, most were young and healthy and their teeth were of a generally good standard, much better than the teeth employed in the majority of dentures. Having been plundered from the battlefield, most of these teeth made their way back to Britain, the country best placed to afford the new top-quality dentures which would incorporate them. These then became known as 'Waterloo Teeth,' a set of which are pictured at right. The name quickly established itself as applying to any set of dentures made from young and healthy teeth taken from a Napoleonic battlefield and continued as a term on into the 19th Century.

While graveyards were a profitable source for cadever teeth, the quantity of teeth typically on hand was limited. Enter the Peninsular Wars and the Battle of Waterloo. Of the 50,000 men who fell at the Battle of Waterloo, most were young and healthy and their teeth were of a generally good standard, much better than the teeth employed in the majority of dentures. Having been plundered from the battlefield, most of these teeth made their way back to Britain, the country best placed to afford the new top-quality dentures which would incorporate them. These then became known as 'Waterloo Teeth,' a set of which are pictured at right. The name quickly established itself as applying to any set of dentures made from young and healthy teeth taken from a Napoleonic battlefield and continued as a term on into the 19th Century. The Quarterly Review 1842 refers to a portion of Bransby Cooper's biography of his uncle, surgeon Sir Astley Cooper, and runs - "Tooth hunters followed the armies, moving in as soon as the living had left the field. `Only let there be a battle and there will be no want of teeth; I'll draw them as fast as the men are knocked down,' says one such hunter in The Life of Astley Cooper. There were so many spare teeth that they were shipped abroad by the barrel. In 1819, American dentist Levi Spear Parmly, the inventor of floss, wrote that he had `in his possession thousands of teeth extracted from bodies of all ages that have fallen in battle.'

"This seems always to have been a regular though subordinate pursuit with them even at home. One of our author's acquaintances, Mr. Murphy, robbed the vault under a London meeting-house, in one night, of teeth which he sold for 60 pounds. No wonder, then, if We find in a subsequent page that one of these fellows returned from Waterloo with a box of teeth and jaw-bones valued at 100 pounds. Did the autumnal beauties of 1816 suspect this? But the most precious harvest of all was, we are told, that of 1813. ' The German universities,' says a French dentist, 'turned out many youths in their very bloom; and our conscripts were so young that few of their teeth had been injured by the stain of tobacco.' The Polish Jews were very active at this work during Napoleon's later campaigns; and we remember a British dentist who was nicknamed Dr. Pulltuski from the notoriety of his dealings with them."

On a more humorous note, it's interesting that at least two books, Modern England 1820-1885 By Oscar Browning and Sir Spencer Walpole's History of England both refer to George IV's false teeth. It seems that the King was set to deliver a speech to Parliament in February of 1825, but had lost his false teeth and so it was delivered, instead, by Lord Eldon.

Separate mineral teeth, designed to be mounted on gold or other plates, which finally gave the death blow to the use of the gleanings of the graveyard, were the invention of a M. Audibran, of Paris, and were introduced into England by Mr. Corbett and their manufacture was taken up by Mr. Claudius Ash, of London, in 1837, who rapidly wrought a marvellous improvement in their strength and beauty, and severed once and for all the gravediggers' connection with the dental surgery. In America, the Civil War continued to provide a source for human teeth.

The following ad appeared in The Solicitor's Journal and Reporter of June 4 1859

TEETH

NO. 9, LOWER GROSVENOR-STREET, GROSVENOR-SQUARE, (Removed from 61). By Her Majesty's Royal Letters Patent. NEWLY-INVENTED APPLICATION of CHEMICALLY PREPARED INDIA-RUBBER in the construction of Artificial Teeth, Gums, and Palates.

MR. EPHRAIM MOSELY, SURGEON-DENTIST, Sole Inventor And Patentee.

A new, original, and invaluable invention, consisting in the adaptation, with the most absolute perfection and success, of CHEMICALLY-PREPARED WHITE and GUM-COLOURED INDIA-RUBBER, as a lining to the gold or bone frame. The extraordinary results of this application may be briefly noted in a few of their most prominent features:—All sharp edges are avoided; no spring wires or fastenings are required; a greatly increased freedom ot snction is supplied ; a natural elasticity, hitherto wholly unattainable, and a fit,perfected with the must unerring accuracy, arc secured; while from the softness and flexibility of the agent employed, the greatest support is given to the adjoining teeth when loose or rendered tender by the absorption of the gums. The acids of the mouth exert no agency on the chemically-prepared India-rubber, and, as it is a non-conductor, fluids of any temperature may be retained in the mouth, all unpleasantness of smell and taste being it the same time wholly provided against by the peculiar nature of its preparation.

The introduction of anaesthesia had a dramatic effect on dentistry. Along with ether and chloroform, nitrous oxide became the most preferred option and most surgeries were equipped with general anaesthetic equipment by the end of the 19th century. Many people were now prepared to have their rotting teeth extracted, which led to an enormous demand for cheap and efficient dentures. The introduction of vulcanite in the mid 19th century meant that dentures could be mass-produced and became affordable, replacing the expensive ivory versions. However, old false teeth apparently still had some value as we read in Methods and Machinery of Practical Banking by Claudius Buchanan Patten (1908) - It is asserted that in these days of poor teeth the average adult has at least a dollar's worth of gold in his mouth, and that, consequently, every generation buries in the cemeteries of the United States 950,000,000 in gold. It may be that in England more economy is shown than here in the disposition of dental deposits, for I have seen in London stores any quantity of old false teeth on sale for the gold that was fixed in them. In the London `Times' it is very common to see a long list of advertisements of second-hand clothing and secondhand false teeth for sale.

The 20th century saw an explosion of new materials, techniques and technology in dentistry. Novocaine was introduced early in the 1900's as a local anaesthetic by a German chemist, Alfred Einhorn. The use of local anaesthetics during dental procedures did much to change the public's attitude towards dentistry. By 1907 the British School Dental Service opened the first UK children's clinic. Toothbrush clubs operated in London schools, and toothbrushes were issued to all serving men during World War I, which extended their use into working class families for the first time.[image error]

Published on June 14, 2011 02:31

June 13, 2011

Lady Butler, Battle Painter - A Surprise Discovery

Victoria here, working on a talk on our trip to Belgium last year (for the 195th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo) on a very rainy weekend, June 18-20, 2010. Thousands of reenactors complete with regalia, horses, tents and camp followers were on display for thousands of tourists and observers, just like Kristine and her daughter Brooke, my husband Ed and me. We were all shivering as we tramped around the muddy fields, much like those soldiers would have done 195 years ago.

Turner, Waterloo, Tate BritainI am presenting a talk on Waterloo: The Battle and the 195th Anniversary at a meeting of The Beau Monde chapter of the Romance Writers of America in New York City on June 28, 2011. In the process of putting together my power point presentation, I came across many paintings of the events leading up to, during and following the battle. A few of them might have been done, as was Turner's, within days or weeks. But most of the paintings were done later in the 19th century, feeding a British taste for celebrating the great moments of the Empire's development.

Turner, Waterloo, Tate BritainI am presenting a talk on Waterloo: The Battle and the 195th Anniversary at a meeting of The Beau Monde chapter of the Romance Writers of America in New York City on June 28, 2011. In the process of putting together my power point presentation, I came across many paintings of the events leading up to, during and following the battle. A few of them might have been done, as was Turner's, within days or weeks. But most of the paintings were done later in the 19th century, feeding a British taste for celebrating the great moments of the Empire's development. The Roll Call, purchased by Queen Victoria, The Royal Collection (portrayuing scene in the Crimean War)

The Roll Call, purchased by Queen Victoria, The Royal Collection (portrayuing scene in the Crimean War)Elizabeth Thompson, later Lady Butler (1846-1933), was born in Switzerland to English parents. She showed early talent for drawing and painting. She was able to study in Italy, and in 1866, entered the Female School of Art in Kensington, London. Eventually in 1873, one of her paintings was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the epitome of achievement for British painters. She went on to further success.

In 1877, she married General Sir William Butler, of Tipperary, and moved with him to many foreign posts having six children along the way. Upon his retirement, they moved to his estate in Ireland. He was an Irish patriot, which did not endear him to the London establishment. Some of his disapproval might have affected Lady Butler, though she continued to paint all her life.

One of her most famous paintings, "Scotland Forever!" shows the Union Brigade, the Inniskillen Scots Greys, at the Battle of Waterloo. It is widely reproduced and beloved of many.

The 28th Regiment at the Battle of Quatre Bras, 1815, is in Melbourne, Australia, at the National Gallery of Victoria. It was painted in 1875, and drawn from the accounts of Captain William Siborne. It shows the 28th (North Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot, on June 16, 1815, a battle leading up to Waterloo.

The Defense of Rorke's Drift as commissioned by Queen Victoria and hangs in the Royal Collection. It portrays a battle during the Zulu War in 1879.

Lady Butler was unusual among the painters of war scenes, most of whom were working long after the battles were over from written accounts. Obviously, she was a woman and most of the others were men. Some observers also point out that she seemed to have more sympathy with the plight of the individual participants in the battles. I do not have a broad enough knowledge of her work to endorse this view, but it seems to ring true.

Butler herself, in her autobiography, wrote: "I never painted for the glory of war, but to portray its pathos and heroism."

[image error]

Published on June 13, 2011 02:00

June 12, 2011

Attempt On The Queen's Life

From The Greville Memoirs

June 12th. (1840) — On Wednesday afternoon, as the Queen and Prince Albert were driving in a low carriage up Constitution Hill, about four or five in the afternoon, they were shot at by a lad of eighteen years old, who fired two pistols at them successively, neither shots taking effect. He was in the Green Park without the rails, and as he was only a few yards from the carriage, and, moreover, very cool and collected, it is marvellous he should have missed his aim. In a few moments the young man was seized, without any attempt on his part to escape or to deny the deed, and was carried off to prison. The Queen, who appeared perfectly cool, and not the least alarmed, instantly drove to the Duchess of Kent's, to anticipate any report that might reach her mother, and, having done so, she continued her drive and went to the Park. By this time the attempt upon her life had become generally known, and she was received with the utmost enthusiasm by the immense crowd that was congregated in carriages, on horseback, and on foot. All the equestrians formed themselves into an escort, and attended her back to the Palace, cheering vehemently, while she acknowledged, with great appearance of feeling, these loyal manifestations. She behaved on this occasion with perfect courage and self-possession, and exceeding propriety; and the assembled multitude, being a high-class mob, evinced a lively and spontaneous feeling for her—a depth of interest which, however natural under such circumstances, must be very gratifying to her, and was satisfactory to witness.