Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 140

September 3, 2011

Travels with Victoria: The British Museum, Part One

[image error]

Saturday 4 June 2011

According the September 2011 British Heritage magazine, the British Museum is the leader of all London attractions, with more than 5,840,000 visitors in 2010. And it is free. Yes, they ask for a contribution and special exhibitions carry an admission fee. But I suspect that many people enjoy hours and hours of browsing without paying a penny. Like most frequent London visitors, I have been many times, but I love to go back because there is always more to see. And I always leave a contribution.

On this particular visit, I was interested in seeing some of the Regency-era acquisitions on display. I have a copy of Louise Allen's Walks Through Regency London guide book. She points out that many of treasures from the late 18th and early 19th centuries can be seen in a few rooms on the upper level. For more information on Louise, her novels and her guidebook, click here. While I had seen -- many times -- the most famous of the British Museum early treasures such as the Rosetta Stone and Elgin Marbles, I realized I really hadn't spent much time looking over the less obvious items.

The display cases on the upper level were well worth close examination. Information comes from the museum's labels. Above, four pedestals in Jasperware by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787, showing Mars, Jupiter, Cupid and Venus. Behind them, a vase with a relief of Aurora in her Chariot in Jasperware by John Turner, about 1790; Turner was the most successful of many imitators of Wedgwood's jasperware.

The display cases on the upper level were well worth close examination. Information comes from the museum's labels. Above, four pedestals in Jasperware by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787, showing Mars, Jupiter, Cupid and Venus. Behind them, a vase with a relief of Aurora in her Chariot in Jasperware by John Turner, about 1790; Turner was the most successful of many imitators of Wedgwood's jasperware.

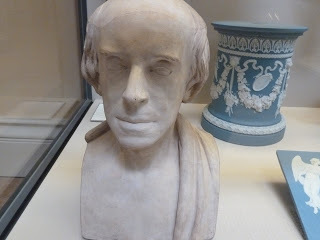

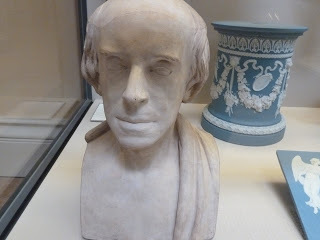

Coadestone bust of John Flaxman, RA (1755-1826), English, London, late 18th century; in 1769, Eleanor Coade (1752-1821) ran a factory making a durable stoneware for outdoor use.

The Pegasus Vase, Jasperware, thrown, with applied reliefs, England, Staffordshire. Josiah Wedgwood, 1786; The main scene designed in 1778 by John Flaxman (above) is the Apotheosis of Homer, copied from a Greek vase bought by the museum in 1763 from the Hamilton Collection.

The Pegasus Vase, Jasperware, thrown, with applied reliefs, England, Staffordshire. Josiah Wedgwood, 1786; The main scene designed in 1778 by John Flaxman (above) is the Apotheosis of Homer, copied from a Greek vase bought by the museum in 1763 from the Hamilton Collection.

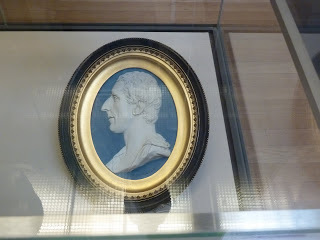

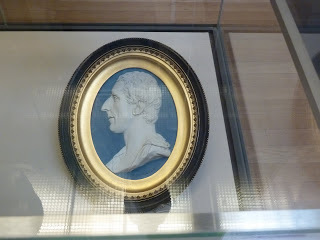

Sir William Hamilton in Jasperware with gild wood frame; England, Staffordshire, Wedgwood, 1779; Hamilton is shown in the guise of a Roman.

An aside: Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803) was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples between 1764 and 1800; he was a scientific observer of Vesuvius, and a collector of antiquities, many of which he shipped home to England and sold to the British Museum in 1772.

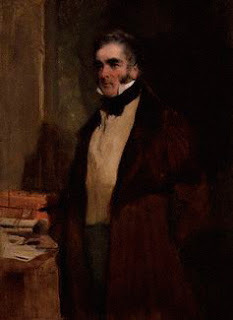

Sir William Hamilton by Reynolds, 1776-77, National Portrait Gallery

Sir William Hamilton by Reynolds, 1776-77, National Portrait Gallery

In 1791, at age 60, Hamilton married Emma Hart, age 26. She accompanied him back to Naples where she met and began a famous liaison with Admiral Horatio Nelson.

Emma, Lady Hamilton by George Romney, c. 1785, National Portrait Gallery

Emma, Lady Hamilton by George Romney, c. 1785, National Portrait Gallery

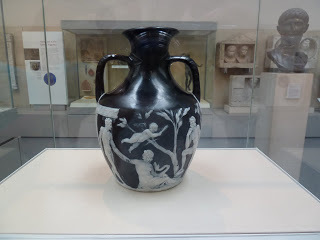

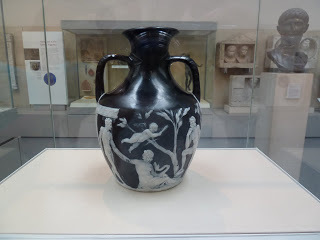

Copy of the Portland Vase; Jasperware, thrown, applied reliefs; England, Staffordshire, Wedgwood, c.1791; between 1786-95, Josiah Wedgwood painstakingly reproduced in black Jasperware the roman glass vase brought to England by Sir William Hamilton and lent to the potter by its owner, the Duke of Portland.

Copy of the Portland Vase; Jasperware, thrown, applied reliefs; England, Staffordshire, Wedgwood, c.1791; between 1786-95, Josiah Wedgwood painstakingly reproduced in black Jasperware the roman glass vase brought to England by Sir William Hamilton and lent to the potter by its owner, the Duke of Portland.

The Portland Vase, made of cameo glass, probably in Rome 15 BC to 25 AD.

The Portland Vase, made of cameo glass, probably in Rome 15 BC to 25 AD.

The Portland Vase is one of the finest surviving pieces of Roman glass; it is named for the Duke of Portland who owned it 1785-1945. Cameo glass is made in two layers; the outer (usually white) layer is carved away from the underlying dark layer to create decorative scenes and patterns.The vase was deliberately smashed in 1845; it was carefully restored by museum conservator John Doubleday; subsequently it has been re-assembled to insure its stability by using new adhesives. It is considered one of the museum's great treasures.

Jasperware Wine Cooler, England, Staffordshire, Etruria c. 1783, Wedgwood; applied relief designed by Lady Diana Beauclerk (1724-1808).

Jasperware Wine Cooler, England, Staffordshire, Etruria c. 1783, Wedgwood; applied relief designed by Lady Diana Beauclerk (1724-1808).

In a second British Museum post, we will look at a few of the recent developments in the museum itself, as well as a quick visit to the Elgin Marbles.

According the September 2011 British Heritage magazine, the British Museum is the leader of all London attractions, with more than 5,840,000 visitors in 2010. And it is free. Yes, they ask for a contribution and special exhibitions carry an admission fee. But I suspect that many people enjoy hours and hours of browsing without paying a penny. Like most frequent London visitors, I have been many times, but I love to go back because there is always more to see. And I always leave a contribution.

On this particular visit, I was interested in seeing some of the Regency-era acquisitions on display. I have a copy of Louise Allen's Walks Through Regency London guide book. She points out that many of treasures from the late 18th and early 19th centuries can be seen in a few rooms on the upper level. For more information on Louise, her novels and her guidebook, click here. While I had seen -- many times -- the most famous of the British Museum early treasures such as the Rosetta Stone and Elgin Marbles, I realized I really hadn't spent much time looking over the less obvious items.

The display cases on the upper level were well worth close examination. Information comes from the museum's labels. Above, four pedestals in Jasperware by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787, showing Mars, Jupiter, Cupid and Venus. Behind them, a vase with a relief of Aurora in her Chariot in Jasperware by John Turner, about 1790; Turner was the most successful of many imitators of Wedgwood's jasperware.

The display cases on the upper level were well worth close examination. Information comes from the museum's labels. Above, four pedestals in Jasperware by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787, showing Mars, Jupiter, Cupid and Venus. Behind them, a vase with a relief of Aurora in her Chariot in Jasperware by John Turner, about 1790; Turner was the most successful of many imitators of Wedgwood's jasperware.

Coadestone bust of John Flaxman, RA (1755-1826), English, London, late 18th century; in 1769, Eleanor Coade (1752-1821) ran a factory making a durable stoneware for outdoor use.

The Pegasus Vase, Jasperware, thrown, with applied reliefs, England, Staffordshire. Josiah Wedgwood, 1786; The main scene designed in 1778 by John Flaxman (above) is the Apotheosis of Homer, copied from a Greek vase bought by the museum in 1763 from the Hamilton Collection.

The Pegasus Vase, Jasperware, thrown, with applied reliefs, England, Staffordshire. Josiah Wedgwood, 1786; The main scene designed in 1778 by John Flaxman (above) is the Apotheosis of Homer, copied from a Greek vase bought by the museum in 1763 from the Hamilton Collection.

Sir William Hamilton in Jasperware with gild wood frame; England, Staffordshire, Wedgwood, 1779; Hamilton is shown in the guise of a Roman.

An aside: Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803) was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples between 1764 and 1800; he was a scientific observer of Vesuvius, and a collector of antiquities, many of which he shipped home to England and sold to the British Museum in 1772.

Sir William Hamilton by Reynolds, 1776-77, National Portrait Gallery

Sir William Hamilton by Reynolds, 1776-77, National Portrait GalleryIn 1791, at age 60, Hamilton married Emma Hart, age 26. She accompanied him back to Naples where she met and began a famous liaison with Admiral Horatio Nelson.

Emma, Lady Hamilton by George Romney, c. 1785, National Portrait Gallery

Emma, Lady Hamilton by George Romney, c. 1785, National Portrait Gallery Copy of the Portland Vase; Jasperware, thrown, applied reliefs; England, Staffordshire, Wedgwood, c.1791; between 1786-95, Josiah Wedgwood painstakingly reproduced in black Jasperware the roman glass vase brought to England by Sir William Hamilton and lent to the potter by its owner, the Duke of Portland.

Copy of the Portland Vase; Jasperware, thrown, applied reliefs; England, Staffordshire, Wedgwood, c.1791; between 1786-95, Josiah Wedgwood painstakingly reproduced in black Jasperware the roman glass vase brought to England by Sir William Hamilton and lent to the potter by its owner, the Duke of Portland.  The Portland Vase, made of cameo glass, probably in Rome 15 BC to 25 AD.

The Portland Vase, made of cameo glass, probably in Rome 15 BC to 25 AD.The Portland Vase is one of the finest surviving pieces of Roman glass; it is named for the Duke of Portland who owned it 1785-1945. Cameo glass is made in two layers; the outer (usually white) layer is carved away from the underlying dark layer to create decorative scenes and patterns.The vase was deliberately smashed in 1845; it was carefully restored by museum conservator John Doubleday; subsequently it has been re-assembled to insure its stability by using new adhesives. It is considered one of the museum's great treasures.

Jasperware Wine Cooler, England, Staffordshire, Etruria c. 1783, Wedgwood; applied relief designed by Lady Diana Beauclerk (1724-1808).

Jasperware Wine Cooler, England, Staffordshire, Etruria c. 1783, Wedgwood; applied relief designed by Lady Diana Beauclerk (1724-1808).In a second British Museum post, we will look at a few of the recent developments in the museum itself, as well as a quick visit to the Elgin Marbles.

Published on September 03, 2011 01:00

September 1, 2011

Travels with Victoria: Celebrating the Regency in the Queen's Gallery

Last year, when Kristine and Victoria OD'ed on the Queen's Gallery in Buckingham Palace, we enjoyed the exhibition of Victoria and Albert: Art and Love. This spring the kind of love celebrated was the Prince Regent's fondness for art and acquisition. Certainly the two go hand in hand, but the future George IV carried his love for magnificent surroundings to an extreme. His extravagance made him unpopular with politicians and the people, but left us a lasting legacy in the Royal Collection and royal residences. For the RC website, click here.

[image error]

The exhibition devoted to the Regency was suitably opulent. In the center above is the Prince of Wales, portrayed in 1791 by artist John Russell (1745-1806). On each side are two of his siblings in portraits by Sir William Beechey (1754-1839) of the Duke of Cumberland and Princess Augusta. These two were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1802 and by 1805 were hung in Kew Palace.

Here is one of a pair of candelabra by goldsmith Paul Storr (1771-1844); the child is Princess Sophia at age 8 by John Hoppner (1758-1810), exhibited at the RA in 1785; A Rough Dog was painted by royal favorite animal painter, George Stubbs (1724-1806).

The candelabrum of gilt bronze and blue enamel and the pedestal of gilded pine were parts of a set of eight supplied to the Prince about 1794 for the Great Drawing Room of Carlton House. The dealer was Dominique Daguerre, who provided many items made in both England and France.

The magnificent table above was chosen in 1826 for the Crimson Drawing Room in Windsor Castle, one of the last of George IV's elaborate redecoration schemes, which previously included Carlton House, the Brighton Pavilion, and Buckingham House. The Sevres hard-paste porcelain vases were originally in the Brighton Pavilion and later moved to Carlton House. The Prince had an extensive collection of Sevres.

The top of the table is inlaid stones and marbles, a colorful and complicated inset design.

According the label, this pedestal clock was purchased by Francois Benois, the Regent's pastry chef, on one of his trips to France to acquire art for the Prince. Of particular interest was the emblem of Louis XIV, the mask of Apollo; the Regent was an admirer or the French Sun King.

The painting above is Rembrandt van Rijn's The Ship Builder and his Wife (Jan Rycksen and his wife Griet Jans), painted in 1633; at a price of 5,000 guineas, it was the most expensive painting the Prince Regent purchased.

One of a pair of Chinese bottle vases and stands, c. 1814, of porcelain with gilt bronze mounts by Benjamin Vulliamy and stands of marble and ebonized wood; These celadon porcelain vases stood in the Blue Velvet Room at Carlton House; Vulliamy was a clock-maker to George III but was increasingly employed at Carlton House to enhance porcelain objects with decorative gilt bronze mounts.

The center portrait in this grouping is Charles-Alexandre de Calonne, 1784, by Elisabeth-Louis Vigee-Lebrun (1755-1842); Calonne was French finance minister to Louis XVI; his reform suggestions to the king (a copy is held in his hand) might have prevented the French Revolution, but instead he was dismissed and fled to England in 1787; the canvas was purchased by the Prince before 1806.

One of a set of large armchairs, c. 1790. by Francois Herve, made for the Chinese Drawing Room at Carlton House, "perhaps made under the direction of Henry Holland and dealer-decorator Dominique Daguerre. The three men formed part of the highly cultivated Francophile entourage which surrounded the Prince of Wales in the later 1780' and 1790's during the early phase of construction and decoration at Carlton House." (from the label)

The pier table, above, with the candelabra, vases and Chinese Mandarin on the low shelf, were acquired for the Chinese Drawing Room at Carlton House in 1792, the first of a number of Chinese-style rooms created for the Prince of Wales at his various homes, culminating 25 years later with the chinoserie at the Brighton Pavilion.

Since Carlton House was pulled down in 1826, the only pictures of its interior are paintings done in the house, particularly this collection of eight watercolours by Charles Wild (1781-1835). Fortunately, as we have seen in this exhibition, the furniture and decorative objects were moved to other remodeling and construction projects of George IV; his essential and extravagant tastes for exotic and sumptuous theatricality continued into his residences in Brighton, London and Windsor.

This commode is made of ebony, tulipwood, gilt bronze, marble, mirrored glass and a porcelain plaque. It was probably designed under the guidance of French dealer-decorator Daguerre and made by the leading Parisian cabinet maker Adam Weisweiler (1744-1820) in 1785.

In addition to paintings, furniture and decorative objects, the exhibition includes military items, a particular interest of the Prince of Wales. As heir to the throne, he was not allowed to participate directly in the armed forces, but he often designed uniforms, such as the elaborately frogged jacket above. And he collected guns, swords and other paraphernalia as well.

This pair of double barreled flintlock pistols was made by Nicolas-Noel Boutet and presented to the Prince Regent by Louis XVIII of France in 1814 after the first abdication of Napoleon.

Elsewhere in the Queen's Gallery were exhibitions from the Royal Collection focusing on Mythology and Dutch Painting. Many of the objects shown were purchased by the Prince of Wales /George IV. The clock above was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire about 1805 of gilt bronze, marble and blue enamel. From the label: "Apollo was believed by the Romans to be god of the sun. Each day was marked by his emergence from the sea and his journey across the sky in his golden quadriga -- a chariot drawn by four horses abreast -- a cycle illustrated vividly by the clock."

Elsewhere in the Queen's Gallery were exhibitions from the Royal Collection focusing on Mythology and Dutch Painting. Many of the objects shown were purchased by the Prince of Wales /George IV. The clock above was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire about 1805 of gilt bronze, marble and blue enamel. From the label: "Apollo was believed by the Romans to be god of the sun. Each day was marked by his emergence from the sea and his journey across the sky in his golden quadriga -- a chariot drawn by four horses abreast -- a cycle illustrated vividly by the clock."

Also in the Mythology exhibition was this painting of Pan and Syrinx, c. 1620-25, after Sir Peter Paul Rubens, showing a story from Ovid's Metamorphoses about Pan's pursuit of a wood nymph who was transformed into tall reeds as he caught her -- reeds Pan used to make musical instrument -- his pan pipes. The Prince Regent bought this painting in 1812.

In the Dutch Paintings exhibition, this painting by Aelbert Cuyp (1620-1691) "Cows in Pasture beside a River, before Ruins, possibly of the Abbey of Rijnsburg," c. 1645, was acquired by the Prince Regent in 1814. From the label: "Cuyp often employed an unnaturally low viewpoint which forces every form to be silhouetted against the sky, creating a detached effect. In this imaginative view, cows dominate the foreground, with shadowy ruins in the far distance."

The Queen's Gallery in June, 2010

The Queen's Gallery in June, 2010

The Queen's Gallery is open year around with shows drawn from the Royal Collection. during the months when the Queen and royal family are at Balmoral, the State Rooms of the Palace are open, as they are on a few other occasions during the year. See Kristine's post on her visit to the palace 1/9/11. But you can go to the Queen's Gallery any time you are in London; I cannot recommend their exhibitions enough. I have attended many times over the years, and I have never been disappointed. However there is DANGER!! The shop is too tempting to be believed. Click here for a taste of what awaits you if you venture inside. Of course, it's all available on line, but being there is even more toxic to the bank account. Nevertheless, it is wonderful!

Next on Travels with Victoria: the British Museum

[image error]

The exhibition devoted to the Regency was suitably opulent. In the center above is the Prince of Wales, portrayed in 1791 by artist John Russell (1745-1806). On each side are two of his siblings in portraits by Sir William Beechey (1754-1839) of the Duke of Cumberland and Princess Augusta. These two were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1802 and by 1805 were hung in Kew Palace.

Here is one of a pair of candelabra by goldsmith Paul Storr (1771-1844); the child is Princess Sophia at age 8 by John Hoppner (1758-1810), exhibited at the RA in 1785; A Rough Dog was painted by royal favorite animal painter, George Stubbs (1724-1806).

The candelabrum of gilt bronze and blue enamel and the pedestal of gilded pine were parts of a set of eight supplied to the Prince about 1794 for the Great Drawing Room of Carlton House. The dealer was Dominique Daguerre, who provided many items made in both England and France.

The magnificent table above was chosen in 1826 for the Crimson Drawing Room in Windsor Castle, one of the last of George IV's elaborate redecoration schemes, which previously included Carlton House, the Brighton Pavilion, and Buckingham House. The Sevres hard-paste porcelain vases were originally in the Brighton Pavilion and later moved to Carlton House. The Prince had an extensive collection of Sevres.

The top of the table is inlaid stones and marbles, a colorful and complicated inset design.

According the label, this pedestal clock was purchased by Francois Benois, the Regent's pastry chef, on one of his trips to France to acquire art for the Prince. Of particular interest was the emblem of Louis XIV, the mask of Apollo; the Regent was an admirer or the French Sun King.

The painting above is Rembrandt van Rijn's The Ship Builder and his Wife (Jan Rycksen and his wife Griet Jans), painted in 1633; at a price of 5,000 guineas, it was the most expensive painting the Prince Regent purchased.

One of a pair of Chinese bottle vases and stands, c. 1814, of porcelain with gilt bronze mounts by Benjamin Vulliamy and stands of marble and ebonized wood; These celadon porcelain vases stood in the Blue Velvet Room at Carlton House; Vulliamy was a clock-maker to George III but was increasingly employed at Carlton House to enhance porcelain objects with decorative gilt bronze mounts.

The center portrait in this grouping is Charles-Alexandre de Calonne, 1784, by Elisabeth-Louis Vigee-Lebrun (1755-1842); Calonne was French finance minister to Louis XVI; his reform suggestions to the king (a copy is held in his hand) might have prevented the French Revolution, but instead he was dismissed and fled to England in 1787; the canvas was purchased by the Prince before 1806.

One of a set of large armchairs, c. 1790. by Francois Herve, made for the Chinese Drawing Room at Carlton House, "perhaps made under the direction of Henry Holland and dealer-decorator Dominique Daguerre. The three men formed part of the highly cultivated Francophile entourage which surrounded the Prince of Wales in the later 1780' and 1790's during the early phase of construction and decoration at Carlton House." (from the label)

The pier table, above, with the candelabra, vases and Chinese Mandarin on the low shelf, were acquired for the Chinese Drawing Room at Carlton House in 1792, the first of a number of Chinese-style rooms created for the Prince of Wales at his various homes, culminating 25 years later with the chinoserie at the Brighton Pavilion.

Since Carlton House was pulled down in 1826, the only pictures of its interior are paintings done in the house, particularly this collection of eight watercolours by Charles Wild (1781-1835). Fortunately, as we have seen in this exhibition, the furniture and decorative objects were moved to other remodeling and construction projects of George IV; his essential and extravagant tastes for exotic and sumptuous theatricality continued into his residences in Brighton, London and Windsor.

This commode is made of ebony, tulipwood, gilt bronze, marble, mirrored glass and a porcelain plaque. It was probably designed under the guidance of French dealer-decorator Daguerre and made by the leading Parisian cabinet maker Adam Weisweiler (1744-1820) in 1785.

In addition to paintings, furniture and decorative objects, the exhibition includes military items, a particular interest of the Prince of Wales. As heir to the throne, he was not allowed to participate directly in the armed forces, but he often designed uniforms, such as the elaborately frogged jacket above. And he collected guns, swords and other paraphernalia as well.

This pair of double barreled flintlock pistols was made by Nicolas-Noel Boutet and presented to the Prince Regent by Louis XVIII of France in 1814 after the first abdication of Napoleon.

Elsewhere in the Queen's Gallery were exhibitions from the Royal Collection focusing on Mythology and Dutch Painting. Many of the objects shown were purchased by the Prince of Wales /George IV. The clock above was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire about 1805 of gilt bronze, marble and blue enamel. From the label: "Apollo was believed by the Romans to be god of the sun. Each day was marked by his emergence from the sea and his journey across the sky in his golden quadriga -- a chariot drawn by four horses abreast -- a cycle illustrated vividly by the clock."

Elsewhere in the Queen's Gallery were exhibitions from the Royal Collection focusing on Mythology and Dutch Painting. Many of the objects shown were purchased by the Prince of Wales /George IV. The clock above was made by Pierre-Philippe Thomire about 1805 of gilt bronze, marble and blue enamel. From the label: "Apollo was believed by the Romans to be god of the sun. Each day was marked by his emergence from the sea and his journey across the sky in his golden quadriga -- a chariot drawn by four horses abreast -- a cycle illustrated vividly by the clock."

Also in the Mythology exhibition was this painting of Pan and Syrinx, c. 1620-25, after Sir Peter Paul Rubens, showing a story from Ovid's Metamorphoses about Pan's pursuit of a wood nymph who was transformed into tall reeds as he caught her -- reeds Pan used to make musical instrument -- his pan pipes. The Prince Regent bought this painting in 1812.

In the Dutch Paintings exhibition, this painting by Aelbert Cuyp (1620-1691) "Cows in Pasture beside a River, before Ruins, possibly of the Abbey of Rijnsburg," c. 1645, was acquired by the Prince Regent in 1814. From the label: "Cuyp often employed an unnaturally low viewpoint which forces every form to be silhouetted against the sky, creating a detached effect. In this imaginative view, cows dominate the foreground, with shadowy ruins in the far distance."

The Queen's Gallery in June, 2010

The Queen's Gallery in June, 2010The Queen's Gallery is open year around with shows drawn from the Royal Collection. during the months when the Queen and royal family are at Balmoral, the State Rooms of the Palace are open, as they are on a few other occasions during the year. See Kristine's post on her visit to the palace 1/9/11. But you can go to the Queen's Gallery any time you are in London; I cannot recommend their exhibitions enough. I have attended many times over the years, and I have never been disappointed. However there is DANGER!! The shop is too tempting to be believed. Click here for a taste of what awaits you if you venture inside. Of course, it's all available on line, but being there is even more toxic to the bank account. Nevertheless, it is wonderful!

Next on Travels with Victoria: the British Museum

Published on September 01, 2011 01:00

August 30, 2011

The Wellington Connection - Education

From the Duke of Wellington to Lady Shelley

Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818

Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818

London, August 30, 1825.

"My Dear Lady Shelley,

. . . . . . As for John (1) you must impress upon his mind, first, that he is coming into the world at an age at which he who knows nothing will be nothing. If he does not chuse to study, therefore, he must make up his mind to be a hewer of wood and drawer of water to those who do. Secondly, he must understand that there is nothing learnt but by study and application. I study and apply, more, probably, than any man in England.

Thirdly, if he means to rise in the military profession—I don't mean as high as I am, as that is very rare—he must be master of languages, of the mathematics, of military tactics of course, and of all the duties of an officer in all situations.

He will not be able to converse or write like a gentleman—much less to perform with credit to himself the duties on which he will be employed—unless he understands the classics; and by neglecting them, moreover, he will lose much gratification which the perusal of them will always afford him; and a great deal indeed of professional information and instruction.

He must be master of history and geography, and the laws of his country and of nations; these must be familiar to his mind if he means to perform the higher duties of his profession.

Impress all this upon his mind; and moreover tell him that there is nothing like never having an idle moment. If he has only one quarter of an hour to employ, it is better to employ it in some fixed pursuit of improvement of his mind, than to pass it in idleness or listlessness.

Ever, my dearest lady,

Yours most affectionately,

Wellington.

1 John Shelley, Lady Shelley's eldest son, who subsequently joined the Royal Horseguards (Blue).

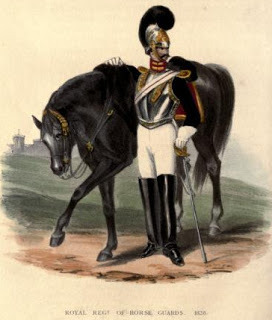

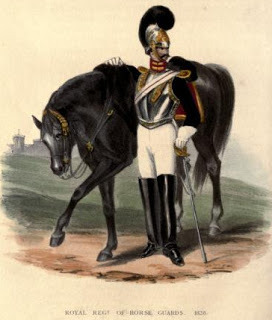

Royal Horse Guards, 1826

Royal Horse Guards, 1826

Woodford, September 18, 1825.

My Dear Lady Shelley,

. . . . In respect to my letter upon education, I don't recollect what I wrote; and I cannot consent to have a copy taken, without first seeing it. You had better send it to me, therefore. Besides, the Tyrant (Mrs. Arbuthnot) says she has no notion of my writing a letter deserving of being copied without her seeing it; and she wishes to ascertain whether I have myself learnt all that I recommend to others to learn. There is no use in disputing about anything, so that you had better send the letter at once.

I will go to Maresfield as soon as I shall have it in my power, after hearing how the Parliament stands.

Believe me, my dearest lady,

Ever yours most affectionately,

Wellington

Postscript written by Mrs. Arbuthnot - "I have no notion of his finishing a letter in such a style; I will never allow that again."

Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818

Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818London, August 30, 1825.

"My Dear Lady Shelley,

. . . . . . As for John (1) you must impress upon his mind, first, that he is coming into the world at an age at which he who knows nothing will be nothing. If he does not chuse to study, therefore, he must make up his mind to be a hewer of wood and drawer of water to those who do. Secondly, he must understand that there is nothing learnt but by study and application. I study and apply, more, probably, than any man in England.

Thirdly, if he means to rise in the military profession—I don't mean as high as I am, as that is very rare—he must be master of languages, of the mathematics, of military tactics of course, and of all the duties of an officer in all situations.

He will not be able to converse or write like a gentleman—much less to perform with credit to himself the duties on which he will be employed—unless he understands the classics; and by neglecting them, moreover, he will lose much gratification which the perusal of them will always afford him; and a great deal indeed of professional information and instruction.

He must be master of history and geography, and the laws of his country and of nations; these must be familiar to his mind if he means to perform the higher duties of his profession.

Impress all this upon his mind; and moreover tell him that there is nothing like never having an idle moment. If he has only one quarter of an hour to employ, it is better to employ it in some fixed pursuit of improvement of his mind, than to pass it in idleness or listlessness.

Ever, my dearest lady,

Yours most affectionately,

Wellington.

1 John Shelley, Lady Shelley's eldest son, who subsequently joined the Royal Horseguards (Blue).

Royal Horse Guards, 1826

Royal Horse Guards, 1826Woodford, September 18, 1825.

My Dear Lady Shelley,

. . . . In respect to my letter upon education, I don't recollect what I wrote; and I cannot consent to have a copy taken, without first seeing it. You had better send it to me, therefore. Besides, the Tyrant (Mrs. Arbuthnot) says she has no notion of my writing a letter deserving of being copied without her seeing it; and she wishes to ascertain whether I have myself learnt all that I recommend to others to learn. There is no use in disputing about anything, so that you had better send the letter at once.

I will go to Maresfield as soon as I shall have it in my power, after hearing how the Parliament stands.

Believe me, my dearest lady,

Ever yours most affectionately,

Wellington

Postscript written by Mrs. Arbuthnot - "I have no notion of his finishing a letter in such a style; I will never allow that again."

Published on August 30, 2011 00:35

August 28, 2011

The Young Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria by Alfred Edward Chalon, 1838,

National Galleries of Scotland

From the Greville Memoirs:

August 30th. (1837) —All that I hear of the young Queen leads to the conclusion that she will some day play a conspicuous part, and that she has a great deal of character. It is clear enough that she had long been silently preparing herself, and had been prepared by those about her (and very properly) for the situation to which she was destined. The impressions she has made continue to be favourable, and particularly upon Melbourne, who has a thousand times greater opportunities of knowing what her disposition and her capacity are than any other person, and who is not a man to be easily captivated or dazzled by any superficial accomplishments or mere graces of manner, or even by personal favour. Melbourne thinks highly of her sense, discretion, and good feeling; but what seem to distinguish her above everything are caution and prudence, the former to a degree which is almost unnatural in one so young, and unpleasing, because it suppresses the youthful impulses which are so graceful and attractive.

Victoria Regina, June 20, 1837, by Henry Tanworth Wells, Royal Collection

On the morning of the King's death, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham arrived at Kensington at five o'clock, and immediately desired to see 'the Queen.' They were ushered into an apartment, and in a few minutes the door opened and she came in wrapped in a dressinggown and with slippers on her naked feet. Conyngham in a few words told her their errand, and as soon as he uttered the words 'Your Majesty,' she instantly put out her hand to him, intimating that he was to kiss hands before he proceeded. He dropped on one knee, kissed her hand, and then went on to tell her of the late King's death. She presented her hand to the Archbishop, who likewise kissed it, and when he had done so, addressed to her a sort of pastoral charge, which she received graciously and then retired. She lost no time in giving notice to Conroy of her intentions with regard to him; she saw him, and desired him to name the reward he expected for his services to her parents. He asked for the Red Eiband, an Irish peerage, and a pension of 3,000l. a year. She replied that the two first rested with her Ministers, and she could not engage for them, but that the pension he should have. It is not easy to ascertain the exact cause of her antipathy to him, but it has probably grown with her growth, and results from divers causes. The person in the world she loves best is the Baroness Lehzen, and Lehzen and Conroy were enemies. There was formerly a Baroness Spaeth at Kensington, lady-in-waiting to the Duchess, and Lehzen and Spaeth were intimate friends. Conroy quarrelled with the latter and got her dismissed, and this Lehzen never forgave. She may have instilled into the Princess a dislike and bad opinion of Conroy, and the evidence of these sentiments, which probably escaped neither the Duchess nor him, may have influenced their conduct towards her, for strange as it is, there is good reason to believe that she thinks she has been ill-used by both of them for some years past.1 Her manner to the Duchess is, however, irreproachable, and they appear to be on cordial and affectionate terms. Madame de Lehzen is the only person who is constantly with her. When any of the Ministers come to see her, the Baroness retires at one door as they enter at the other, and the audience over she returns to the Queen. It has been remarked that when applications are made to Her Majesty, she seldom or never gives an immediate answer, but says she will consider of it, and it is supposed that she does this because she consults Melbourne about everything, and waits to have her answer suggested by him. He says, however, that such is her habit even with him, and that when he talks to her upon any subject upon which an opinion is expected from her, she tells him she will think it over, and let him know her sentiments the next day.

Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, 1786-1861 by Sir George Hayter, 1835Royal Collection

Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, 1786-1861 by Sir George Hayter, 1835Royal CollectionThe day she went down to visit the Queen Dowager at Windsor, to Melbourne's great surprise she said to him that as the flag on the Round Tower was half-mast high, and they might perhaps think it necessary to elevate it upon her arrival, it would be better to send orders beforehand not to do so. He had never thought of the flag, or knew anything about it, but it showed her knowledge of forms and her attention to trifles. Her manner to the Queen was extremely kind and affectionate, and thej were both greatly affected at meeting. The Queen Dowager said to her that the only favour she had to ask of her was to provide for the retirement, with their pensions, of the personal attendants of the late King, Whiting and Bachelor, who had likewise been the attendants of George IV.; to which she replied that it should be attended to, but she could not give any promise on the subject.

William Lamb, Lord Melbourne (1779-1848), by Sir Edwin Landseer 1838

National Portrait Gallery

She is upon terms of the greatest cordiality with Lord Melbourne, and very naturally. Everything is new and delightful to her. She is surrounded with the most exciting and interesting enjoyments; her occupations, her pleasures, her business, her Court, all present an unceasing round of gratifications. With all her prudence and discretion she has great animal spirits, and enters into the magnificent novelties of her position with the zest and curiosity of a child.

Published on August 28, 2011 00:33

August 27, 2011

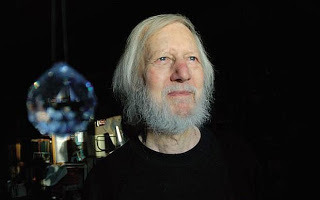

The Passing of Hilary Evans

Married to Mary Evans, who passed away last year, Hilary Evans and his wife created the Mary Evans Picture Library, an invaluable London-based resource known to all historians and researchers. As if that achievment was not monumental in itself, Mr. Evans was also a serious UFO researcher and a collector of arcane beers and their brewing methods. Additionally, Evans wrote three novels and two non-fiction books on the Victorian era. In short, Evans, had he lived during the last centuries, would surely have gone down in the history books as one of those unique and quirky personalities we love so well. You can read his full obituary here.

Published on August 27, 2011 07:04

August 26, 2011

Gossip Between Lady Shelley and Mrs. Arbuthnot

Harriette, Mrs. Arbuthnot by Richard Cosway

copyright Artchives.com

Mrs. Arbuthnot to Lady Shelley

Woodford, Wednesday [no date].

"My Dear Lady Shelley, What an age it is since I have written to you! but my house has been so full; and I have been so full of regret at not being in the north hearing all the speeches and witnessing all the applause with which the Duke was received everywhere. Lady Bathurst and Sir Henry Harding have written me long accounts of it, all which is lucky for the Duke (of Wellington), as I should (very unjustly) be in a fury with him, for he enters into no details. To be sure one could not expect him to plume himself on his success; and, as I have heard it from others, I am satisfied. They are all enchanted with him, and he has done everything quite right, as he always does. I have Lord and Lady Francis Gower here and Mr. Greville and Lady Charlotte. Do you not think Mr. Greville the most agreeable man you know? I do; he has so much gossip, and tells a story so well. He has just been saying, God forgive me! but I wish Canning had lived to undergo the mortification of this visit of the Duke's to the north; it would have been a good lesson to him, and would have killed him.' He is in very good humour, and bears with my small house with the greatest fortitude. I am quite sorry they are going, which they do tomorrow for Chatsworth. Lady Charlotte is grown fearfully old and wrinkled. Lord Westmorland comes here to-morrow and stays till Saturday, on which day we go to Drayton.

We go to Apethorpe (pictured above) on Wednesday next. How all the ladies seem to be increasing in these days of over-population; it is quite surprising, and Mrs. Griffiths is in despair, for I understand they all come together. Lady Jersey, you know, always publishes it immediately. I did not know the Duke had been so sly about his visit there, but I am greatly amused at your not daring to quiz him; I did not think you had been so shy! especially with him. Do you know any news of our wise Ministers? what they mean to do with Turkey and Portugal? Never was such a condition as they have placed us in, I think, but they may thank the master mind for that. Poor Lord Dudley must be at his wits' end, I think, with these perpetual conferences and interviews that one reads of. Pray write and tell me the London news, for I hear none of the Newmarket news. I see Sir John has a match. Ever, my dear Lady Shelley,"Yours very affly., "H. A."

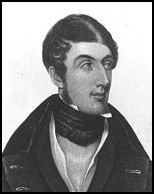

George Canning

August 10, 1827."My Dear Lady Shelley, "Thank you for sending me an account of the Duke. I am very glad you think he looks well. He writes me word he is quite well again. I got both your letters the same day, as he did not frank your Monday one till Tuesday. Poor Mr. Canning! I daresay you will not agree with me, but I am really very sorry for him. In the first place I had much rather have had a fight with him next session, and beat him in that way, and secondly, I hate to have anybody die. I cannot feel rancour against the dead; and, fatally mischievous as he has been to us, I cannot help pitying him. He has suffered so horribly, mind as well as body! depend upon it his has been a bed of thorns; nothing can have been more humiliating and degrading than all he has endured in the last four months. He was the vainest man that ever lived, with the quickest and most irritable feelings, and I know he felt his position most acutely. I have quite longed to write to Planta, to enquire after him; but I have not, for I should very likely have been accused of hypocrisy. I only hope our newspapers will not abuse him, tho' to be sure the abuse heaped upon us just now by the Times is quite laughable. One thing I do rather enjoy, and that is the consternation in which our rats must be, such as your friend Sir George Clerk, etc., etc., etc. I have no guess what will happen, but I do not expect the King will send for any of us now. It will be, to use his own words, poor man, a curious coincidence if he dies the same day as Queen Caroline! Metternich's remark about our luck is certainly just; but how he made out that the new parliament in South America could have anything to do with the Berlin Decrees I don't understand. I am delighted to hear Mr. Peel has taken Maresfield; he cannot fail to like it, and the joy of getting it off your hands will help to restore you. I have been reading 'Falkland.' I like it very much, all but the ghost. 1 don't suppose it is very moral, but I think it is natural and well written. Have you read it? I have also read 'Judge Jeffreys,' which I don't like at all, and think it very ill done; I have no patience with the author who apologises for such an inhuman beast. I am now reading General Foy, who puts me in a rage with his fulsome praise of French soldiers and their mildness and kindneartedness! I had a letter from the Duke of Rutland to-day. Lady C. Powlett had been there for a night; she went from here. I think I shall put her nose, and Mrs. Foxs', out of joint in that quarter, and yours too; His Grace writes so very tenderly. I don't know how I shall manage them in Derbyshire; I shall have to sing the old song ' How happy could I be with either, were t'other dear Duke but away'—but that would be a copy of my countenance; there is but one Duke worth thinking about in the world, in my opinion. But do not show up that I joke about the other; it is only to amuse you, and he is very goodnatured and kind to me, and I like him, and would not laugh about him on any account, but you know he has a sentimental way with him. I shall write to the Duke about Mr. L. Wellesley, for a madman is never to be despised. I hope nothing fresh has happened?

Ever, my dear Lady Shelley, Yours affly.,

"H. A."

Published on August 26, 2011 00:12

August 24, 2011

Travels with Victoria: The Gardens of Westminster Abbey

On Sunday, June 12, 2011, on a rainy day, I decided to attend services at the Abbey in advance of my visits to the gardens of the area. Since it was a sung service, the Abbey was crowded with tourists and worshippers alike. Did you know that the official name for the Abbey is the Collegiate Church of St. Peter, Westminster, and it is classified as a "Royal Peculiar." Here is the website.

On Sunday, June 12, 2011, on a rainy day, I decided to attend services at the Abbey in advance of my visits to the gardens of the area. Since it was a sung service, the Abbey was crowded with tourists and worshippers alike. Did you know that the official name for the Abbey is the Collegiate Church of St. Peter, Westminster, and it is classified as a "Royal Peculiar." Here is the website.

The beauty of the choral works and the magnificence of the organ were every bit as impressive as they were the previous month at the royal wedding. The morning's sermon was excellent, delivered by The Venerable Jane Hedges, cannon of the Abbey. She was kind enough to explain to me later that the "Venerable" in her title is just a traditional term for her office, not descriptive!

At the conclusion of the service, the Abbey bells performed a long peal ( I think that is the proper term; for more info click here). The beautiful bells accompmanied most of my ramble around the Abbey Gardens, all open for the Open Squares Weekend, 2011.

The College Garden, according to the Abbey Garden brochure, "Is reputed to be the oldest in England and was originally an isolated piece of land inside the Thames called 'Thorney Island'....

"...After the Dissolution of the monasteries in 1540, it became an area of recration for the clergy. In more recent years, an attempt has been made to acknowledge the Garden's original use by planting vegetables, herbs and fruit trees."

From the College Garden, the Abbey is right next door, and the bells were continuing with great beauty.

Above, St. Catherine's Garden includes the ruins of the Chapel of St. Catherine, built in the 12th century, once the abbey infirmary.

The Little Cloister provided peaceful silence and respite for the monks, now perhaps the most visited of the Abbey Gardens, for it is often open when the others are not.

Sadly, I did not wander much further since the rain continued. I was also eager to get to my next stop, the Queen's Gallery, for an exhibition honoring the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the Regency in 1811, coming soon.

Published on August 24, 2011 01:00

August 22, 2011

Funeral Horses

From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon (1893)

This funeral business is a strange one in many respects, but, just as the jobmaster is in the background of the every-day working world, so the jobmaster is at the back of the burying world. The 'funeral furnisher' is equal to all emergencies on account of the facilities he possesses for hiring to an almost unlimited extent, so long as the death rate is normal. The wholesale men, the 'black masters,' are always ready to cope with a rate of twenty per thousand —London's normal is seventeen—but when it rises above that, as it did in the influenza time, the pressure is so great that the 'blacks' have to get help from the 'coloured,' and the 'horse of pleasure' becomes familiar with the cemetery roads.

A hundred years ago there was but one black master in London. He owned all the horses; and there are wonderful stories of the funerals in those days when railways were unknown. The burying of a duke or even a country squire, in the family vault, was then a serious matter, for the body had to be taken the whole distance by road, and the horses were sometimes away for a week or more, and were often worked in relays, much on the same plan as the coach-horses, only that rapid progress through the towns and villages was impossible, for the same reason that no living undertaker dare trot with a tradesman within the limits of the district in which the deceased happens to have been known and respected. Even nowadays the black masters of London can be counted on one's fingers, the chief, according to general report, being Dottridge, of East Road.

A wonderful place is Dottridge's. It is the centre of what may be called the wholesale undertaking trade, where the retail undertakers are themselves undertaken and supplied with all they need, from coffin to tombstone. From all parts of the country telegrams and letters are continually coming in and packages continually going out by carrier and fast train, all labelled 'immediately for funeral,' to insure quick delivery. If anyone wants a parcel to go promptly and surely to hand, he has only to label it with these mystic words, and the railway men will pounce upon it and be off with it at a run—that is, if they treat it as we saw them do with the first one that came under our notice, which they handled as if it had arrived red hot, and was required at its destination before it cooled. 'Haste,' `urgent,' ' immediate,' are but poor incentives to speed compared with the red funeral label, such as was once accidentally stuck on a boy's hamper, and sent the matron into hysterics as it was hurriedly bumped on to the school door-mat.

Altogether there are about 700 of these black horses in London. They are all Flemish, and come to us from the flats of Holland and Belgium by way of Rotterdam and Harwich. They are the youngest horses we import, for they reach us when they are rising three years old, and take a year or so before they get into full swing; in fact, they begin work as what we may call the 'halftimers' of the London horse-world. When young they cost rather under than over a hundred guineas a pair, but sometimes they get astray among the carriage folk, who pay for them, by mistake of course, about double the money. In about a year or more, when they have got over their sea-sickness and other ailments, and have been trained and acclimatised, they fetch 65L. each; if they do not turn out quite good enough for first-class -work they are cleared out to the second-class men at about twenty-five guineas; if they go to the repository they average 10L; if they go to the knacker's they average thirty-five shillings, and they generally go there after six years' work. Most of them are stallions, for Flemish geldings go shabby and brown. They are cheaper now than they were a year or two back, for the ubiquitous American took to buying them in their native land for importation to the States, and thereby sent up the price; but the law of supply and demand came in to check the rise, and some enterprising individual actually took to importing black horses here from the States, and so spoilt the corner.

Here, in the East Road, are about eighty genuine Flemings, housed in capital stables, well built, lofty, light, and well ventilated, all on the ground floor. Over every horse is his name, every horse being named from the celebrity, ancient or modern, most talked about at the time of his purchase, a system which has a somewhat comical side when the horses come to be worked together.

One would think these horses were big, black retriever dogs, to judge by the liking and understanding which spring up between them and their masters. It is astonishing what a lovable, intelligent animal a horse is when he finds he is understood. According to popular report these Flemish stallions are the most vicious and ill-tempered of brutes; but those who keep them and know them are of the very opposite opinion.

The funeral horse hardly needs description. The breed has been the same for centuries. He stands about sixteen hands, and weighs between 12 and 13 cwt. The weight behind him is not excessive, for the car does not weigh over 17 cwt., and even with a lead coffin he has the lightest load of any of our draught horses. The worst roads he travels are the hilly ones to Highgate, Finchley, and Norwood. These he knows well and does not appreciate. In a few months he gets to recognise all the cemetery roads 'like a book,' and after he is out of the bye streets he wants practically no driving, as he goes by himself, taking all the proper corners and making all the proper pauses. This knowledge of the road has its inconveniences, as it is often difficult to get him past the familiar corner when he is out at exercise. But of late he has had exercise enough at work, and during the influenza epidemic was doing his three and four trips a day, and the funerals had to take place not to suit the convenience of the relatives, but the available horse-power of the undertaker. Six days a week he works, for after a long agitation there are now no London funerals on Sundays, except perhaps those of the Jews, for which the horses have their day's rest in the week.

To feed such a horse costs perhaps two shillings a day—-it is a trifle under that, over the 700—and his food differs from that of any other London horse. In his native Flanders he is fed a good deal upon slops, soups, mashes, and so forth; and as a Scotsman does best on his oatmeal, so the funeral horse, to keep in condition, must have the rye-bread of his youth. Ryebread, oats, and hay form his mixture, with perhaps a little clover, but not much, for it would not do to heat him, and beans and such things are absolutely forbidden. Every Saturday he has a mash like other horses, but unlike them his mash consists, not of bran alone, but of bran and linseed in equal quantities. What the linseed is for we know not; it may be, as a Life Guardsman suggested to us, to make his hair glossy, that beautiful silky hair which is at once his pride and the reason of his special employment, and the sign of his delicate, sensitive constitution.

Published on August 22, 2011 01:00

August 21, 2011

Happy Birthday William IV

Happy Birthday to King William IV, whose birthday I share. In order to celebrate our birthdays, my husband, Greg, and I went out to dinner with friends to the Capital Grill last night.

Here's a snap Greg took of my girlfriend Mary Ann and I -

And here's another

We ate, drank and laughed lots. A good time was had by all.

However, I must say that in all honesty the real star of the evening was neither King William nor myself, but instead was Greg's four pound lobster.

Published on August 21, 2011 06:21

August 20, 2011

Charles Greville on Lord and Lady Holland from 1841

Charles Cavendish Fulke Greville (1794 – 1865) kept a journal during his many years as an associate of the poltical and social leadership of Great Britain. He was essentially a well-born gentleman of leisure who knew "everyone" and went "everywhere." You can access all his work on-line at Project Gutenberg. Greville characterizes Lady Holland's domineering style as she chides a respected historian, below.

Charles Greville

Charles Greville

From The Greville Memoirs (Second Part), "A Journal of the Reign of Queen Victoria from 1837 to 1852" (Volume 1 of 3) by Charles C. F. Greville"December 31st, 1840: The end of the year is a point from which, as from a sort of eminence, one looks back over the past… That which has made the deepest impression on society is the death of Lord Holland. I doubt, from all I see, whether anybody (except his own family, including Allen) had really a very warm affection for Lord Holland, and the reason probably is that he had none for anybody. He was a man with an inexhaustible good humour, and an ever-flowing nature,but not of strong feelings; and there are men whose society is always enjoyed but who never inspire deep and strong attachment. I remember to have heard good observers say that Lady Holland had more feeling than Lord Holland--would regret with livelier grief the loss of a friend than this equable philosopher was capable of feeling. The truth is social qualities--merely social and intellectual--are not those which inspire affection. A man may be steeped in faults and vices, nay, in odious qualities, and yet be the object of passionate attachment, if he is only what the Italians term '_simpatico_.'…

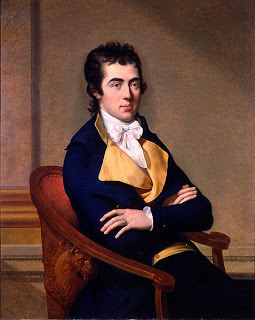

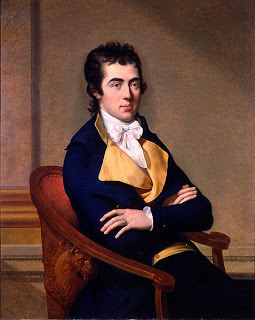

Henry Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, c. 1795

Henry Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, c. 1795

"January 21st, 1841: I dined with Lady Holland yesterday. Everything there is exactlythe same as it used to be, excepting only the person of Lord Holland, who seems to be pretty well forgotten. The same talk went merrily round, the laugh rang loudly and frequently, and,but for the black and the mob-cap of the lady, one might have fancied he had never lived or had died half a century ago. Such are, however, affections and friendships, and such is the world.

Holland House, 1896

Holland House, 1896

"Macaulay dined there, and I never was more struck than upon this occasion by the inexhaustible variety and extent of his information...It is impossible to mention any book in any language with which he is not familiar; to touch upon any subject, whether relating to persons or things, on which he does not know everything that is to be known. And if he could tread less heavily on the ground, if he could touch the subjects he handles with a lighter hand, if he knew when to stop as well as he knows what to say, his talk would be as attractive as it is wonderful. What Henry Taylor said of him is epigrammatic and true, 'that his memory has swamped his mind;'…

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859)"We had yesterday a party well composed for talk, for there were listeners of intelligence and a good specimen of the sort of society of this house--Macaulay, Melbourne, Morpeth, Duncannon, Baron Rolfe, Allen and Lady Holland, and John Russell came in the evening. I wish that a shorthand writer could have been there to take down all the conversation, or that I could have carried it away in my head;…

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859)"We had yesterday a party well composed for talk, for there were listeners of intelligence and a good specimen of the sort of society of this house--Macaulay, Melbourne, Morpeth, Duncannon, Baron Rolfe, Allen and Lady Holland, and John Russell came in the evening. I wish that a shorthand writer could have been there to take down all the conversation, or that I could have carried it away in my head;…

Elizabeth, Lady Holland (1770-1845), c. 1793

Elizabeth, Lady Holland (1770-1845), c. 1793

" ...and then the name of Sir Thomas Munro came uppermost. Lady Holland did not know why Sir Thomas Munro was so distinguished; when Macaulay explained all that he had ever said, done, written, or thought, and vindicated his claim to the title of a great man, till Lady Holland got bored with Sir Thomas, told Macaulay she had had enough of him, and would have no more. This would have dashed and silenced an ordinary talker, but to Macaulay it was no more than replacing a book on its shelf, and he was as ready as ever to open on any other topic….

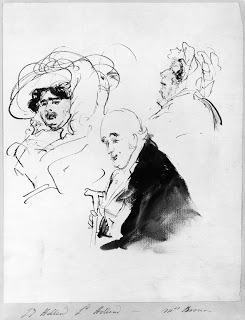

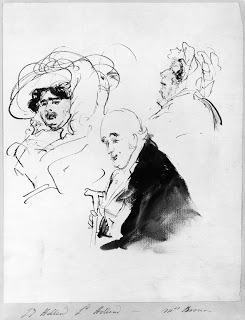

sketch by Sir Henry Landseer of Lady Holland, Lord Holland and Mrs. Brown (maid)

sketch by Sir Henry Landseer of Lady Holland, Lord Holland and Mrs. Brown (maid)

c. 1833, National Portrait Gallery" It would be impossible to follow and describe the various mazes of conversation, all of which he threaded with an ease that was always astonishing and instructive, and generally interesting and amusing…. 'I remember a sermon,' he said, 'of Chrysostom's in praise of the Bishop of Antioch;' and then he proceeded to give us the substance of this sermon till Lady Holland got tired of the Fathers, again put her extinguisher on Chrysostom as she had done on Munro…"

Charles Greville

Charles GrevilleFrom The Greville Memoirs (Second Part), "A Journal of the Reign of Queen Victoria from 1837 to 1852" (Volume 1 of 3) by Charles C. F. Greville"December 31st, 1840: The end of the year is a point from which, as from a sort of eminence, one looks back over the past… That which has made the deepest impression on society is the death of Lord Holland. I doubt, from all I see, whether anybody (except his own family, including Allen) had really a very warm affection for Lord Holland, and the reason probably is that he had none for anybody. He was a man with an inexhaustible good humour, and an ever-flowing nature,but not of strong feelings; and there are men whose society is always enjoyed but who never inspire deep and strong attachment. I remember to have heard good observers say that Lady Holland had more feeling than Lord Holland--would regret with livelier grief the loss of a friend than this equable philosopher was capable of feeling. The truth is social qualities--merely social and intellectual--are not those which inspire affection. A man may be steeped in faults and vices, nay, in odious qualities, and yet be the object of passionate attachment, if he is only what the Italians term '_simpatico_.'…

Henry Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, c. 1795

Henry Vassall Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, c. 1795"January 21st, 1841: I dined with Lady Holland yesterday. Everything there is exactlythe same as it used to be, excepting only the person of Lord Holland, who seems to be pretty well forgotten. The same talk went merrily round, the laugh rang loudly and frequently, and,but for the black and the mob-cap of the lady, one might have fancied he had never lived or had died half a century ago. Such are, however, affections and friendships, and such is the world.

Holland House, 1896

Holland House, 1896"Macaulay dined there, and I never was more struck than upon this occasion by the inexhaustible variety and extent of his information...It is impossible to mention any book in any language with which he is not familiar; to touch upon any subject, whether relating to persons or things, on which he does not know everything that is to be known. And if he could tread less heavily on the ground, if he could touch the subjects he handles with a lighter hand, if he knew when to stop as well as he knows what to say, his talk would be as attractive as it is wonderful. What Henry Taylor said of him is epigrammatic and true, 'that his memory has swamped his mind;'…

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859)"We had yesterday a party well composed for talk, for there were listeners of intelligence and a good specimen of the sort of society of this house--Macaulay, Melbourne, Morpeth, Duncannon, Baron Rolfe, Allen and Lady Holland, and John Russell came in the evening. I wish that a shorthand writer could have been there to take down all the conversation, or that I could have carried it away in my head;…

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859)"We had yesterday a party well composed for talk, for there were listeners of intelligence and a good specimen of the sort of society of this house--Macaulay, Melbourne, Morpeth, Duncannon, Baron Rolfe, Allen and Lady Holland, and John Russell came in the evening. I wish that a shorthand writer could have been there to take down all the conversation, or that I could have carried it away in my head;… Elizabeth, Lady Holland (1770-1845), c. 1793

Elizabeth, Lady Holland (1770-1845), c. 1793" ...and then the name of Sir Thomas Munro came uppermost. Lady Holland did not know why Sir Thomas Munro was so distinguished; when Macaulay explained all that he had ever said, done, written, or thought, and vindicated his claim to the title of a great man, till Lady Holland got bored with Sir Thomas, told Macaulay she had had enough of him, and would have no more. This would have dashed and silenced an ordinary talker, but to Macaulay it was no more than replacing a book on its shelf, and he was as ready as ever to open on any other topic….

sketch by Sir Henry Landseer of Lady Holland, Lord Holland and Mrs. Brown (maid)

sketch by Sir Henry Landseer of Lady Holland, Lord Holland and Mrs. Brown (maid)c. 1833, National Portrait Gallery" It would be impossible to follow and describe the various mazes of conversation, all of which he threaded with an ease that was always astonishing and instructive, and generally interesting and amusing…. 'I remember a sermon,' he said, 'of Chrysostom's in praise of the Bishop of Antioch;' and then he proceeded to give us the substance of this sermon till Lady Holland got tired of the Fathers, again put her extinguisher on Chrysostom as she had done on Munro…"

Published on August 20, 2011 01:00

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.