Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 138

October 10, 2011

Visiting Corsham Court with Victoria

Corsham Court is near Chippenham in Wiltshire. The website is here.

Corsham Court, which I photographed in 2009 on a visit to Hampshire and Wiltshire, was a Royal manor in the time of Saxon Kings. The core of the present house was built in the late 16th century by Thomas Smyth. In the 1740's, the estate was purchased by a member of the Methuen family and eventually altered to house Sir Paul Methuen's excellent collection of paintings. Almost two centuries later, more fine pictures were added when the family inherited the collection of a relative who had resided in Italy where he acquired many old masters. The initial impression of the house exterior reminded me of a previous visit to the Biltmore estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North Carolina

Biltmore Estate, Asheville, North CarolinaBiltmore, the home of George Vanderbilt in North Carolina, opened in 1895, the creation of architect William Morris Hunt; he based his designs on the style of three 16th C French chateaux.

A closer look at the entrance of Corsham Court.

A closer look at the entrance of Corsham Court. At Corsham Court, the Elizabethan house was altered significantly several times. In 1798, architect John Nash followed in Capability Brown's footsteps (see below) but could not keep up! Sadly, Nash's work was poorly executed and needed significant repair within a few decades. So in the 1840's, parts of the house were rebuilt again, giving it the look it now has by architect Thomas Bellamy. I find both the Court and Biltmore rather forbidding in appearance. However, the interior of Corsham Court could not be more different from Biltmore. I felt Biltmore was dark, dreary, and altogether uninviting as a place to live (to visit, quite fascinating).

An angled view of one wing.

An angled view of one wing. Corsham Court is lovely, beginning with a handsome hall, that I would call a combination of neo-classic and baroque, as interpreted by Bellamy in the Victorian Age.

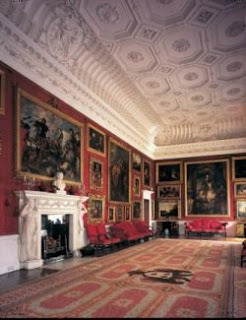

The Picture Gallery, a triple cube room, 72 feet long, was designed by Lancelot Capability Brown in the 1760's. Brown is renowned for his hundreds of landscape garden designs, but he is also responsible for a number of country houses, some fully, others remodeling projects.

Brilliant works by Van Dyke, Strozzi, Dolci, Reni, del Sarto, Rosa, and others fill the walls in the state rooms – an astonishing collection, mostly still owned by the Methuen family. According to the Blue Guide to English Country Houses, "The pictures themselves, still hung much as they were in the 18C, many of them in their original frames, offer an almost unparalleled insight into 18C artistic taste." From the house guide book, "In 1765 Morris & Young of Spitalfields supplied 700 yards at 13 s. 6d. a yard, and four years later a further 478 1/2 yards at 14 s. the latter amount for covering the furniture. As time went by, the damask on the chairs got worn, and so sections were cut from behind the paintings to patch them."

Among the most renowned paintings in the collection is Van Dyke's Betrayal of Christ, above, now actually owned by the City of Brisol Art Gallery.

Lady Boston, nee Christiana Methuen by George Romney

Lady Boston, nee Christiana Methuen by George RomneyI love to look at the family portraits as well as the Old Masters since knowing the stories of the families who lived in the great stately homes is a big part of the fun. Christian Methuen died in 1832.

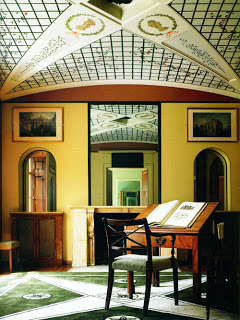

The Cabinet RoomAlmost as renowned as the art collections at Corsham Court are the gardens, some dating from the days of Capability Brown and others developed in the last decades.

The Cabinet RoomAlmost as renowned as the art collections at Corsham Court are the gardens, some dating from the days of Capability Brown and others developed in the last decades.

I had my usual luck with peacocks. Despite my begging, they just weren't interested in display!

In fact, this fellow just stalked away with a haughty expression. "Don't bother me," he seemed to say.

This charming structure leads to the bathhouse, originally designed by Brown but altered by others to its present neo-Gothic look.

Below is another view which shows the now-empty plunge bath, once a popular feature of country houses -- and probably useful too.

It must have been lovely on a warm day to soak in the bath and gaze out on the beautiful garden blooms.

It must have been lovely on a warm day to soak in the bath and gaze out on the beautiful garden blooms.

Corsham Court is as great country house, well worth visiting.

For a detailed history of the house:http://www.corsham-court.co.uk/Court%20history/Commentary.htmlMore information on the collections and reproductions of the paintings can be seen here:http://www.corsham-court.co.uk/Pictures/Commentary.html

Published on October 10, 2011 02:00

October 8, 2011

For Sale: Bath, England

Well . . . I've been looking at property listings again. And I've found one that's a right pip, and also offers fantastic views of the city of bath. As the property listing tells us:

Rainbow Wood House, which is unlisted, was specially designed and built in Jacobean revival style in 1897 for the Mallett family, who at the time owned most of the land around Rainbow Woods, including what is now the Bath Clinic and Rainbow Wood Farm. Rainbow Wood House, which is unlisted, is positioned in a spectacular hillside position that affords complete privacy being located a quarter of a mile from the nearest road, Widcombe Hill. Surrounded by mature trees and its own gardens, the house is so secluded that very few Bathonians know the property exists.

The Malletts were well known in Bath and London for their antique business and donated many of their properties and much of their land, including the farm which adjoins Rainbow Wood House, to the National Trust. The present owners acquired the property from the Mallett family in 1980 and are only the second family to reside at the Rainbow Wood estate.

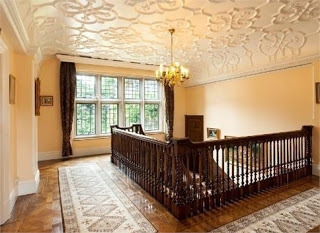

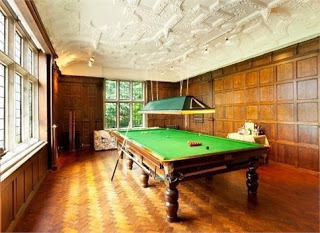

Rainbow Wood House is constructed of Bath stone under a tiled roof and has an array of splendid features from the stone mullions to the gables and bronze, iron and steel framed windows. The reception space is exceptionally impressive having many ornate features that adorn the walls and ceilings in many of the rooms. Of particular note are the half panelled reception hall, a magnificent Edwardian staircase, the fully panelled Oak Room and numerous hand carved doors and original fireplaces. Rainbow Wood House has an interconnected North Wing, which provides substantial additional self-contained accommodation that lends itself to becoming an integral part of the main house. This wing houses the magnificent oak panelled gallery, which is currently used as a snooker and games room.

The house has a gas fired central heating system throughout, with radiators in all rooms including the workshop and attic, modern electrics, a modern alarm system and outside security lights. All main services are connected.

The estate gardens and grounds that encircle Rainbow Wood House are sensational. The extensive lawns are defined and embellished with carved stone features and balustrades and a range of herbaceous borders and mature trees. There are a number of ornamental ponds and a fountain, a central walk leading to the stone built Gothic Temple and a large, original stone walled garden having an abundance of fruit trees. On the top lawns there is a hard tennis court. There is also a two acre grass paddock with wrought iron 'estate' fencing..

Ancillary accommodation includes a three bedroom lodge built in the same style as the main house, and a two bedroom gardeners cottage.

The principal outlook is to the south and west overlooking its own gardens, National Trust fields and woodlands and there are far-reaching views over the city towards Bristol and the distant Welsh hills. Despite the seclusion of its position, the house is less than a 5 minute drive from the centre of Bath. In all, the estate has about 13 acres. Guide price £5,500,000 - FreeholdFor complete details, visit the Savills Bath website.

Published on October 08, 2011 00:23

October 6, 2011

The Darker Side of London History

From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon (1893)

Very few horses are allowed to end their days in peace, after long and faithful service, like the Duke of Wellington's old charger Copenhagen, in the paddocks at Strathfieldsaye. London horses, in particular, rarely die natural deaths. Many of them are sent back into the country in a vain hope that they will 'come round'; many of them are poleaxed for very shame at their miserable appearance; some of them slip and injure themselves beyond recovery in the streets.

A curious trade is that of the horse-slaughterer, who must not only have a licence, but carry on his operations in accordance with the 26th of George III. and other Acts of Parliament. No horse that enters his yard must come out again alive, or as a horse. The moment it enters those gates it must be disfigured by having its mane cut off so close to the skin as to spoil its value, and though it may be put in a 'pound' on the premises, which might better be called a condemned cell or a moribundary, it must not remain there for more than three days.

In Garratt Lane, Wandsworth, is the largest horseslaughtering yard in London. It has existed for about a hundred years. There it stands, practically odourless, by the banks of the winding Wandle, with a wide meadow in front of it and a firework factory next door, the magazine of which is within measurable distance of its boiler-house. One fine morning—it was really a beautiful morning—we found our way down the lane, along the field, armed with Mr. Boss's permit, to be initiated by Mr. Milestone into the mysteries of a horse's departure from the London world.

The last scene does not take long. In two seconds a horse is killed; in a little over half an hour his hide is in a heap of dozens, his feet are in another heap, his bones are boiling for oil, his flesh is cooking for cat's meat. Maneless he stands; a shade is put over his eyes; a swing of the axe, and, with just one tremor, he falls heavy and dead on the flags of a spacious kitchen, which has a line of coppers and boilers steaming against two of its walls.

In a few minutes his feet are hooked up to crossbeams above, and two men pounce upon him to flay him; for the sooner he is ready the quicker he cooks. Slash, slash, go the knives, and the hide is peeled off about as easily as a tablecloth; and so clean and uninjured is the body that it looks like the muscle model we see in the books and in the plaster casts at the corn-chandler's. Then, with full knowledge gained by almost life-long practice, for the trade is hereditary, the meat is slit off with razor-like knives, and the bones are left white and clean and yet unscraped, even the neck vertebrae being cleared in a few strokes—one of the quickest things in carving imaginable.

If there is any malformation the sweep of the knife is stayed for a moment; that is all. The same sort of thing has always been seen before, and there is no hesitation about the way to deal with it. No matter of what breed or age or condition the horse may be, his 'boning' is not delayed by peculiarities. And horses of all sorts, some of them sound and in the prime of life, here meet their doom—the favourite horse killed at his master's death, to save him from falling into cruel hands: the runaway horse that has injured a daughter; the brute that has begun to kick and bite; the mildest mannered mare that has, perhaps, merely taken a wrong turn and made her mistress angry—all come here to die with the hundreds of the injured and the old. Taking them all round, the old and young and sound and ailing, they average out in the men's opinion at rather over eleven years when they here meet their doom.

Soon the bare skeleton remains to be broken upj and in baskets go aloft to be shot into a huge digester, where it is made to yield about a quarter hundredweight of oil. Following the oil, we see it cleared of its stearin, pressed out between huge sheets of paper, and remaining in white cakes like gauffres ready for the candle-makers; and we see the oil flowing limpid and clear into the tank above, from which it is barrelled off to be used eventually for lubricating and leather-dressing purposes.

Returning to the bones, we find them out on the flags, clean and free from grease, ready to be thrown into a mill, from which they emerge like granite from a stonebreaker, along a sloping cylindrical screen, which sorts the fragments into sizes varying up to half an inch. And stretching away from us are sacks, full to the brim with bones, all in rows like flour-sacks at a miller's, all ready to go off to the manure merchants. And still further following the bones, we find some of them ground to powder and mixed with sulphuric acid to leave the premises as another form of fertiliser.

Having seen the bones off the premises, we follow the feet, of which we find a huge pile, not a trace of which will be left before the day is out. The skin and hoofs will go to the glue-makers and blue-makers; the bones will go to the button-makers; the old shoes will go to the farrier's and be used over and over again, welded in the fire and hammered on the streets, so that all that is lost of a horseshoe is what rusts or is rubbed off in powder..-.

With a glance at the tails and manes, which will soon be lost in sofas, chairs, or fishing-lines, we reach the heap of hides, which will probably find its way to Germany to be made into the leather guards on cavalry trousers, or, maybe, stay in this country for carriage roofs and whip-lashes. This distribution of the dead horse may seem to be an odoriferous business, but the odours are reduced to a minimum by an elaborate ventilating system which draws off all the fumes and emanations into a line of pipes, and passes them over a wide furnace to be burnt, so that none of them reach the outer air.

But now for the 'meat,' which, cut into such joints as the trade require, has been boiling in the coppers and is now done to a turn, with just the central tint of redness and rawness that suits the harmless, necessary cat, while the 'tripe ' is doing white in another copper to suit the palate of the less fastidious dog.

Harrison Barber, Limited, the successors of the once great Jack Atcheler, dead some thirty years since, kill 26,000 London horses a year. All night and all day the work goes on, this slaying and flaying, and boning and boiling down, and this cooking for feline food. Go to any of their depots between five and six o'clock in the morning, and you will find a long string of the pony traps and hand-carts, barrows and perambulators, used in the wholesale and retail cat's-meat trade. The horse on an average yields 2 cwt. 3 qrs. of meat; 26,000 horses a year means 500 a week, which in its turn means 70 tons of meat per week to feed the dogs and cats of London.

This is not all the 'meat' that is sold, nor all the London horses that are killed, for the horseflesh trade is large enough to employ thirty wholesale salesmen; but taking even this ten tons a day, we shall find it means 134,400 meals, inasmuch as a pound of meat cuts up into half a dozen ha'porths—the skewers being given in, though it takes half a ton of them to fix up a day's consumption. Here is another item for the forest conservation people! 182 tons of deal used a year in skewering up the horses made into meat by Harrison Barber!

Sometimes there is a glut of the aged and the maimed, and the supply of meat exceeds the demand. To cope with this difficulty a complete refrigerating plant is at work at Wandsworth, cooling the larders, in which two hundred and fifty horses can be stored; which larders are not only a revelation, but a welcome surprise.

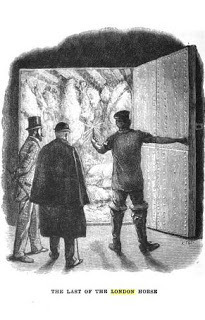

A door is opened and shut, and we stand in the darkness between two doors in an air lock; the inner door is opened and a shiver of cold runs through us as a match is struck and a candle lighted; and there in front is what looks like a deep cave in an arctic drift. Around us are piles of meat, all hard as stone and glittering with ice crystals; overhead, and at the back of all, the beams and walls are thick with pure clinging snow; and from above a few flakes fall as the door closes on the silvery cloak that wraps the last to leave the Horse World of London.

Published on October 06, 2011 00:46

October 4, 2011

The Sale Yard

From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon (1893)

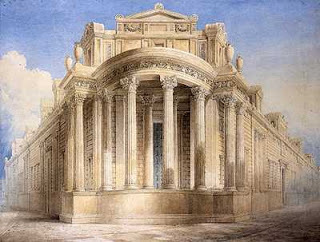

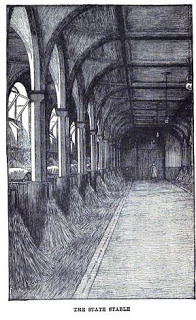

Tattersall's is usually looked upon as the headquarters of horsey London. It is certainly the headquarters of the horse of pleasure, but, as has been made clear enough in these pages, that sort of horse is simply lost in the thousands that throng our streets. Tattersall's is practically the great betting exchange, but the visitor to any of the Monday or Thursday sales will be puzzled to find the least sign of a betting atmosphere at Knightsbridge. The two things are as distinct on those days as, say, the Bank of England and Capel Court. The yard is under cover, a lofty glass-roofed hall, which cost 30,000L to build, and which is as big as many a railway station. It is surrounded by a handsome gallery, behind the arched and columned screen of which every type of pleasure vehicle seems to be 'on view,' duly numbered in 'lots ' for the hammer. In the centre of the gravel area is a drinking fountain, surmounted by the quaint old Georgian bust of the founder, with its eyes fixed on the entrance doors, and its thoughts apparently as far away from water as are those of the crowd around.

It is a different variety of crowd from that which gathers in any other sale yard. London has several 'repositories.' There is Aldridge's in St. Martin's Lane; there is Kymill's in the Barbican—these two being the chief; and there are Stapleton's out in the East, and Ward's in the West, and the Elephant and Castle in the South, and others which many a horse knows well. There is a sort of horse that' knows the lot'; the sort that' does the round,' and brings more money to the auctioneers than to the unfortunate buyers, who ' find him out' in a fortnight, and ' get rid of him sharp 'to an unwary successor; a wonderful animal this horse, 'quiet in harness, a good worker,' who has only two faults, one that ' it takes a long time to catch him in a field,' the other that ' he is not worth a rap when caught.' But this kind of horse does not put in many appearances at Knightsbridge. Tattersall's has a character to keep up, and it has kept it up for over a hundred years now. It is eminently respectable, from the unused drinking fountain and the auctioneers' hammer, one of the good old pattern, with a rounded knob instead of a double head, down to the humblest hanger-on.

Entering one of the stables which open on to the yard, and have a dozen or more roomy stalls apiece, wefind a horse being measured, to make sure he is correctly described. One would think he was a recruit, from the careful way in which the long wooden arm is brought down so gingerly as not even to press in his skin. Soon his turn will come. Up in the gallery will go his number, and the young auctioneer in the rostrum below —which has a sounding-board, as if it were a cathedral pulpit—will read out his short title.

Out comes the horse at last—tittuppy-trot, tittuppytrot. 'Ten,' says one of the crowd. 'Ten guineas,' echoes the auctioneer. 'Twelve,' comes from the crowd; 'twelve guineas,' echoes the 'Varsity man in the pulpit. And so the game goes on with nods and shouts, each nod or look being worth a guinea, so that the solo runs, 'Thirteen—thirteen guineas—fourteen guineas—fifteen guineas—sixteen—sixteen guineas— seventeen—eighteen—twenty guineas'—quite a singsong up to—' twenty-eight guineas'—and so gradually slowing, with a spurt or two to ' forty guineas'—and then a grand noisy rally till 'fifty-five' is reached. 'Fifty-five ?—Fifty-five ?—Fifty-five? Last time, Fiftyfive !'—knock—and away goes Captain Carbine's hunter, to make room for a 'match pair' that will change hands at 165 guineas, or perhaps fifty more if the season has begun—the bidding always in guineas, in order that the auctioneer may live on the shillings, as Sir John Gilbert used to do in the old days when the guineas flowed to him for his drawings on the wood.

If you want riding horses or carriage horses you go to Tattersall's; if you want draught horses for trade, you go to Bymill's or Aldridge's, where you not only get the new-comers, but also the second-hand, and many-another-hand, from London's stables. With those second-hand horses we need not overburden ourselves; our task has been to bring the first-hand horses into London, and sort them out. We have brought in the 'bus horses, the tram horses, the cab horses, the railway horses, the cart and many other horses. Of the cart horses we could, if it were worth while, say a good deal more. We have said nothing of the distillers, the millers, the soap merchants, the timber merchants, the better class contractors, and half a dozen other firsthand horse-owning trades. Some of the distillers' horses are said, by those who know, to be as good as any in the brewers' drays, and by 'as good' is meant that they are of the same breeding, and can be compared with them, owing to their being at somewhat similar work.

If you think you know anything of horseflesh and want the conceit taken out of you, by all means attend a repository sale. You will see a horse—it may be a likely mare—led from her stall and stood ready for her turn, and you will probably value her at, to be reasonable, 20L; and she looks worth not a penny less. When her number goes up at the window you will see her shown at her best at a run, and, for a moment, you will be inclined to add hi. to your estimate, But soon a chill will run down your back as you hear the bidding. 'Three! Three and a half! Four!' a long pause. 'Four and a half! Five!' jerks the auctioneer in the corner, with about as much expression as if a penny had been put in his mouth to work him automatically. 'For the last time! Five!' Knock. Five guineas! And as the mare is led back to her stall she seems to Change before your very eyes, and you are ready to admit that she doesn't look worth a penny more!

Published on October 04, 2011 00:30

October 2, 2011

From the Pen of Horace Walpole

Horace Walpole

Horace WalpoleTo John Chute, Esquire.Paris, Oct. 3, 1765.

I don't know where you are, nor when I am likely to hear of you. I write at random, and, as I talk, the first thing that comes into my pen. I am, as you certainly conclude, much more amused than pleased. At a certain time of life, sights and new objects may entertain one, but new people cannot find any place in one's affection. New faces with some name or other belonging to them, catch my attention for a minute—I cannot say many preserve it. Five or six of the women that I have seen already are very sensible. The men are in general much inferior, and not even agreeable. They sent us their best, I believe, at first, the Due de Nivernois. Their authors, who by the way are everywhere, are worse than their own writings, which I don't mean as a compliment to either. In general, the style of conversation is solemn, pedantic, and seldom animated, but by a dispute. I was expressing my aversion to disputes: Mr. Hume, who very gratefully admires the tone of Paris, having never known any other tone, said with great surprise, "Why, what do you like, if you hate both disputes and whisk?"

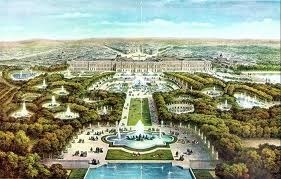

Palace of Versailles

Palace of VersaillesWhat strikes me the most upon the whole is, the total difference of manners between them and us, from the greatest object to the least. There is not the smallest similitude in the twenty-four hours. It is obvious in every trifle. Servants carry their lady's train, and put her into her coach with their hat on. They walk about the streets in the rain with umbrellas to avoid putting on their hats; driving themselves in open chaises in the country without hats, in the rain too, and yet often wear them in a chariot in Paris when it does not rain. The very footmen are powdered from the break of day, and yet wait behind their master, as I saw the Duc of Praslin's do, with a red pocket-handkerchief about their necks. Versailles, like everything else, is a mixture of parade and poverty, and in every instance exhibits something most dissonant from our manners. In the colonnades, upon the staircases, nay in the antechambers of the royal family, there are people selling all sorts of wares. While we were waiting in the Dauphin's sumptuous bedchamber, till his dressing-room door should be opened, two fellows were sweeping it, and dancing about in sabots to rub the floor.

Louis, Dauphin of France

Louis, Dauphin of FranceYou perceive that I have been presented. The Queen took great notice of me; none of the rest said a syllable. You are let into the King's bedchamber just as he has put on his shirt; he dresses and talks good-humouredly to a few, glares at strangers, goes to mass, to dinner, and a-hunting. The good old Queen, who is like Lady Primrose in the face, and Queen Caroline in the immensity of her cap, is at her dressing-table, attended by two or three old ladies, who are languishing to be in Abraham's bosom, as the only man's bosom to whom they can hope for admittance. Thence you go to the Dauphin, for all is done in an hour. He scarce stays a minute; indeed, poor creature, he is a ghost, and cannot possibly last three months. The Dauphiness is in her bedchamber, but dressed and standing; looks cross, is not civil, and has the true Westphalian grace and accents. The four Mesdames, who are clumsy plump old wenches, with a bad likeness to their father, stand in a bedchamber in a row, with black cloaks and knotting-bags, looking goodhumoured, not knowing what to say, and wriggling as if they wanted to make water. This ceremony too is very short; then you are carried to the Dauphin's three boys, who you may be sure only bow and stare. The Duke of Berry looks weak and weak-eyed: the Count de Provence is a fine boy; the Count d'Artois well enough. The whole concludes with seeing the Dauphin's little girl dine, who is as round and as fat as a pudding.

In the Queen's antechamber we foreigners and the foreign ministers were shown the famous beast of the Gevaudan, just arrived, and covered with a cloth, which two chasseurs lifted up. It is an absolute wolf, but uncommonly large, and the expression of agony and fierceness remains strongly imprinted on its dead jaws.*

I dined at the Due of Praslin's with four-and-twenty ambassadors and envoys, who never go but on Tuesdays to court. He does the honours sadly, and I believe nothing else well, looking important and empty. The Due de Choiseul's face, which is quite the reverse of gravity, does not promise much more. His wife is gentle, pretty, and very agreeable. The Duchess of Praslin, jolly, red-faced, looking very vulgar, and being very attentive and civil. I saw the Due de Richelieu in waiting, who is pale, except his nose, which is red, much wrinkled, and exactly a remnant of that age which produced General Churchill, Wilks the player, the Duke of Argyll, &c. Adieu!

* More from Walpole on the Beast in a letter to the Hon. H.S. Conway, October 6, 1765: Yes, the wild beast, he of the Gevaudan. He is killed, and actually in the Queen's antechamber, where he was exhibited to us with as much parade as if it was Mr. Pitt. It is an exceedingly large wolf, and, the connoisseurs say, has twelve teeth more than any wolf ever had since the days of Romulus's wet-nurse. The critics deny it to be the true beast; and I find most people think the beast's name is legion, for there are many. He was covered with a sheet, which two chasseurs lifted up for the foreign ministers and strangers.

Published on October 02, 2011 01:39

September 30, 2011

Regency Reflections: Pitshanger Manor and Dulwich Picture Gallery

Sir John Soane (1784-1837) was a distinguished architect in Georgian England whose works have received at great deal of attention from 20th and 21st century architects. His work was unique for his time and appealing to the contemporary sensibility, both then and now. For information on his London home and museum, see the blog post of 9/24/11. This post will discuss two more of his buildings, Pitshanger Manor and the Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Pitshanger Manor, Ealing, Greater LondonSoane had a well established practice and had completed most work on his own London home in Lincoln's Inn Fields by 1800. He wanted a villa west of the city where he, his wife and two sons could enjoy country life. He purchased 28 acres for £ 4,500 including an existing house and outbuildings, known as Pitshanger Manor. Eventually, he demolished most of the existing structures, saving only a wing designed by his mentor, architect George Dance, in the 1770's for previous owners. Over the next few years, Soane and his students worked on the house. Almost all of the drawings and receipts for the construction, decoration and furnishing of the house have been preserved in Sir John Soane's Museum.

Pitshanger Manor, Ealing, Greater LondonSoane had a well established practice and had completed most work on his own London home in Lincoln's Inn Fields by 1800. He wanted a villa west of the city where he, his wife and two sons could enjoy country life. He purchased 28 acres for £ 4,500 including an existing house and outbuildings, known as Pitshanger Manor. Eventually, he demolished most of the existing structures, saving only a wing designed by his mentor, architect George Dance, in the 1770's for previous owners. Over the next few years, Soane and his students worked on the house. Almost all of the drawings and receipts for the construction, decoration and furnishing of the house have been preserved in Sir John Soane's Museum.

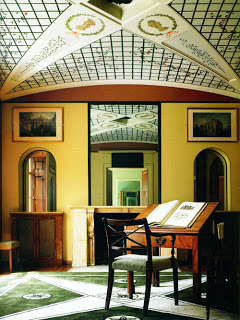

Library, Pitshanger ManorLondon has spread out quite a bit and Pitshanger Manor is now in a park in the suburb of Ealing, reachable by the Underground, amidst an affluent bedroom community. In the early 20th century, the building had become the local library, with an addition for additional space. Since the mid-80's, it has been opened to the public and carefully restored to the look of Soane's day, except for the addition which is used for small art exhibitions.

Library, Pitshanger ManorLondon has spread out quite a bit and Pitshanger Manor is now in a park in the suburb of Ealing, reachable by the Underground, amidst an affluent bedroom community. In the early 20th century, the building had become the local library, with an addition for additional space. Since the mid-80's, it has been opened to the public and carefully restored to the look of Soane's day, except for the addition which is used for small art exhibitions.

Breakfast Room., Pitshanger ManorThe interiors are clearly neo-classic, but have a distinctly contemporary feel. One can easily see why post-modernists are attracted to Soane's work. The breakfast room has walls with marbled effects, a popular technique used by today's designers.

Breakfast Room., Pitshanger ManorThe interiors are clearly neo-classic, but have a distinctly contemporary feel. One can easily see why post-modernists are attracted to Soane's work. The breakfast room has walls with marbled effects, a popular technique used by today's designers.

Dulwich Picture GalleryIn another section of suburban London, the Dulwich Picture Gallery attracts many visitors to its collection of Old Masters. It is Britain's first purpose-built public picture gallery, and Soane's design set the standard for every art museum since. The Picture Gallery is located on the campus of Dulwich College, established in the early 17th century in the village of Dulwich, where it today serves about 1600 boys, ages 7 to 18.

Dulwich Picture GalleryIn another section of suburban London, the Dulwich Picture Gallery attracts many visitors to its collection of Old Masters. It is Britain's first purpose-built public picture gallery, and Soane's design set the standard for every art museum since. The Picture Gallery is located on the campus of Dulwich College, established in the early 17th century in the village of Dulwich, where it today serves about 1600 boys, ages 7 to 18.

The Picture Gallery came about as a result of several coincidences A London art dealer Noel Desenfans (1745-1807) was asked by the King of Poland to assemble paintings for a national collection in 1790. However, within a few years, Poland had been divided up among Austria, Prussia and Russia. Desenfans tried to sell the collection but met with no success. Therefore he decided, with the help of his friend, Francis Bourgeois, to set up a public gallery. After his death, Bourgeois willed the collection to Dulwich College. His friend Sir John Soane designed the building, which also includes a mausoleum for Mr. and Mrs. Desenfans and Bourgeois.

Soane's design was unique, using extensive skylights to bring in natural light. Building began on October 12, 1811. Originally there were five galleries on either side of the mausoleum and flanked by almshouses, which were later converted to additional galleries. Further additions have been kept in sympathy with the original designs.

Girl Leaning on a Window-sill, Rembrandt

Girl Leaning on a Window-sill, Rembrandt

The collection contains many gems, some dating from the establishment of the original college, many from the Desenfans collection, others from more recent acquisitions. The Gallery's website is here.

The Madonna of the Rosary: Murillo

The Madonna of the Rosary: Murillo

Thomas Linley (1732-95) and his son, also Thomas (1756-98) were famous composers and musical performers in Georgian England, along with Elizabeth and Mary, the elder Thomas's daughters. They were good friends of the renowned portraitist Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) who painted all of them. Gainsborough's portrait of the Linley Sisters, below, was part of a bequest of Linley family portraits to the Gallery. Elizabeth Linley (in blue) was painted just before she eloped and eventually married Richard Brinsley Sheridan, playwright and politician.

The Linley Sisters by Gainsborough

The Linley Sisters by Gainsborough

Two hundred years after its establishment, the Dulwich Picture Gallery is thriving; it has won many awards for its extensive educational programs. It stands as a tribute to its founders and to the designer of its trail-blazing building, Sir John Soane.

Pitshanger Manor, Ealing, Greater LondonSoane had a well established practice and had completed most work on his own London home in Lincoln's Inn Fields by 1800. He wanted a villa west of the city where he, his wife and two sons could enjoy country life. He purchased 28 acres for £ 4,500 including an existing house and outbuildings, known as Pitshanger Manor. Eventually, he demolished most of the existing structures, saving only a wing designed by his mentor, architect George Dance, in the 1770's for previous owners. Over the next few years, Soane and his students worked on the house. Almost all of the drawings and receipts for the construction, decoration and furnishing of the house have been preserved in Sir John Soane's Museum.

Pitshanger Manor, Ealing, Greater LondonSoane had a well established practice and had completed most work on his own London home in Lincoln's Inn Fields by 1800. He wanted a villa west of the city where he, his wife and two sons could enjoy country life. He purchased 28 acres for £ 4,500 including an existing house and outbuildings, known as Pitshanger Manor. Eventually, he demolished most of the existing structures, saving only a wing designed by his mentor, architect George Dance, in the 1770's for previous owners. Over the next few years, Soane and his students worked on the house. Almost all of the drawings and receipts for the construction, decoration and furnishing of the house have been preserved in Sir John Soane's Museum. Library, Pitshanger ManorLondon has spread out quite a bit and Pitshanger Manor is now in a park in the suburb of Ealing, reachable by the Underground, amidst an affluent bedroom community. In the early 20th century, the building had become the local library, with an addition for additional space. Since the mid-80's, it has been opened to the public and carefully restored to the look of Soane's day, except for the addition which is used for small art exhibitions.

Library, Pitshanger ManorLondon has spread out quite a bit and Pitshanger Manor is now in a park in the suburb of Ealing, reachable by the Underground, amidst an affluent bedroom community. In the early 20th century, the building had become the local library, with an addition for additional space. Since the mid-80's, it has been opened to the public and carefully restored to the look of Soane's day, except for the addition which is used for small art exhibitions.  Breakfast Room., Pitshanger ManorThe interiors are clearly neo-classic, but have a distinctly contemporary feel. One can easily see why post-modernists are attracted to Soane's work. The breakfast room has walls with marbled effects, a popular technique used by today's designers.

Breakfast Room., Pitshanger ManorThe interiors are clearly neo-classic, but have a distinctly contemporary feel. One can easily see why post-modernists are attracted to Soane's work. The breakfast room has walls with marbled effects, a popular technique used by today's designers.  Dulwich Picture GalleryIn another section of suburban London, the Dulwich Picture Gallery attracts many visitors to its collection of Old Masters. It is Britain's first purpose-built public picture gallery, and Soane's design set the standard for every art museum since. The Picture Gallery is located on the campus of Dulwich College, established in the early 17th century in the village of Dulwich, where it today serves about 1600 boys, ages 7 to 18.

Dulwich Picture GalleryIn another section of suburban London, the Dulwich Picture Gallery attracts many visitors to its collection of Old Masters. It is Britain's first purpose-built public picture gallery, and Soane's design set the standard for every art museum since. The Picture Gallery is located on the campus of Dulwich College, established in the early 17th century in the village of Dulwich, where it today serves about 1600 boys, ages 7 to 18.

The Picture Gallery came about as a result of several coincidences A London art dealer Noel Desenfans (1745-1807) was asked by the King of Poland to assemble paintings for a national collection in 1790. However, within a few years, Poland had been divided up among Austria, Prussia and Russia. Desenfans tried to sell the collection but met with no success. Therefore he decided, with the help of his friend, Francis Bourgeois, to set up a public gallery. After his death, Bourgeois willed the collection to Dulwich College. His friend Sir John Soane designed the building, which also includes a mausoleum for Mr. and Mrs. Desenfans and Bourgeois.

Soane's design was unique, using extensive skylights to bring in natural light. Building began on October 12, 1811. Originally there were five galleries on either side of the mausoleum and flanked by almshouses, which were later converted to additional galleries. Further additions have been kept in sympathy with the original designs.

Girl Leaning on a Window-sill, Rembrandt

Girl Leaning on a Window-sill, RembrandtThe collection contains many gems, some dating from the establishment of the original college, many from the Desenfans collection, others from more recent acquisitions. The Gallery's website is here.

The Madonna of the Rosary: Murillo

The Madonna of the Rosary: MurilloThomas Linley (1732-95) and his son, also Thomas (1756-98) were famous composers and musical performers in Georgian England, along with Elizabeth and Mary, the elder Thomas's daughters. They were good friends of the renowned portraitist Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) who painted all of them. Gainsborough's portrait of the Linley Sisters, below, was part of a bequest of Linley family portraits to the Gallery. Elizabeth Linley (in blue) was painted just before she eloped and eventually married Richard Brinsley Sheridan, playwright and politician.

The Linley Sisters by Gainsborough

The Linley Sisters by GainsboroughTwo hundred years after its establishment, the Dulwich Picture Gallery is thriving; it has won many awards for its extensive educational programs. It stands as a tribute to its founders and to the designer of its trail-blazing building, Sir John Soane.

Published on September 30, 2011 02:20

September 28, 2011

Musing About Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House, home to the Cavendish family since 1549, has been labelled the 'Palace of the Peak' and features more than 30 rooms, a large library and magnificent collections of paintings and sculpture. Additionally, the grounds include a 105-acre garden and a park on the banks of the river Derwent. Recently, and apropos of absolutely nothing, I was musing about Chatsworth and concluded that it remains my personal favourite when it comes to Stately Homes. There are many reasons for this:

1. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, once lived there.

2. So did the Duke and Bess Foster.

3. When you arrive at Chatsworth House on a visit, you're likely to be cautioned to mind the present Duchess's chickens, who are allowed to wander, willy nilly, in the grounds.

4. During a visit to Chatsworth House in 1843 by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the Orangery in the grounds (above), designed by Joseph Paxton, served as the inspiration for Prince Albert's idea for the design of the Crystal Palace.

5. Chatsworth House features the hands down, absolute best gift shops. Seriously good. There are six of them. All with different themes and goods. Go prepared and bring an empty carry-all with you. Trust me on this.

Copyright Chatsworth House

Copyright Chatsworth House6. You can gaze upon the Gainesborough portrait of Georgiana (see Number 1 above), which has a long and twisted history. For the full story, click here to read a previous blog post about the theft of the painting. And by the way, you can purchase a print of the image directly from Chatsworth House by clicking here.

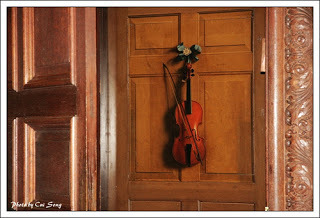

7. The trompe l'oeil door and violin in the State Music Room painted by artist Jan van der Vaart circa 1723. Your first glimpse of the masterpiece will be from afar. Bear in mind that the inner door, the violin and bow and the silver knob from which they appear to be "hanging" are all an illusionist painting.

Copyright burgessbroadcast.org

Copyright burgessbroadcast.org Copyright pbase.com

Copyright pbase.com Copyright Song on Flicker

Copyright Song on FlickerThe next time you're in or near the Peak District, I urge you to visit Chatsworth House. If you've already been, make a return visit and take in all that you missed the first time around. In the meantime, you can watch a stunning slideshow of Chatsworth House images here.

Published on September 28, 2011 00:30

September 26, 2011

Speaking of Bridget Jones . . .

And really, these days who isn't speaking of her? Not only is Bridget Jones 3 in the works, there's soon to be a musical based on the story. Tapped to play the lead role in Bridget Jones: The Musical, actress Sheridan Smith is currently enjoying pigging out in order to gain weight for the role, unlike Renee Zellweger, who emphatically said that she wasn't willing to gain a pound when Bridget Jones 3 goes into production.

A svelte Zellweger at LAX on July 9

A svelte Zellweger at LAX on July 9Sheridan said: "I can just eat what I want. At the minute I've been eating burgers and it's great. I'm not really one for eating salads anyway, but the fact that I have to put on weight is even better.

"There will be a lot of dancing, that's the thing - it's just wondering whether you can keep it on doing eight shows a week. But I'll eat loads don't worry!

"Chocolate, cakes burgers, pizza, the lot. All my favourite foods. Jamie Oliver would kill me for saying things like that wouldn't he?!"

British pop star Lily Allen was chosen to write the music for the show and recently confirmed to Britain's Elle magazine that she is almost finished writing the songs, and that we can expect the musical to hit in London's West End in 2012. The play will be scripted by Bridget Jones author Fielding and produced by Working Title.

No concrete word yet on who will playing Mark Darcy or Daniel Cleaver. Stay tuned . . .

Published on September 26, 2011 00:21

September 24, 2011

Regency Reflections: Sir John Soane's Museum

Victoria here. People often ask me what I recommend for their visits to London. I always answer, if they are in search of the English Regency, Sir John Soane's Museum in Lincoln's Inn Fields. It is free (contribution requested) and of a perfect size for a half-day visit. The museum website is here. The portrait above is Sir John is by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Sir John Soane (1753-1837) was a brilliant architect and teacher. The museum is in his house and classrooms, so you will get a taste of a wealthy (but not aristocratic) residence plus all Sir John's collections, used for the instruction of his architecture students.

The bust of Sir John Soane in the center of the picture above was sculpted by Sir Francis Chantrey (1781-1841). Watch for my upcoming blog post on Chantrey, soon.

Above, many rooms of the museum are devoted to the material he collected for his students to study. Sir John began his career working for architects George Dance and, later, Henry Holland. He traveled to Italy to study and came back to London to begin his own practice, in which he prospered, often doing projects to expand, remodel and modernize the country houses of the wealthy. An example, below, is Moggerhanger House in Bedfordshire, finished in 1812 and updated as a conference center in recent years. More information is here.

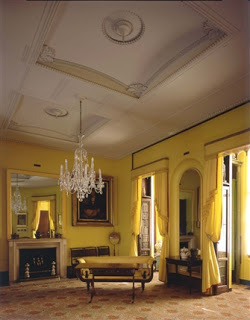

Sir John Soane's Museum shows several rooms in which his family lived, and I have always found the Drawing Room amusing. It's very brilliant shade of yellow furnishings was a very popular color during the Regency, as evidenced in a number of country houses (such as Goodwood House).

Whether you visit on a sunny or a rainy, gray day, this room will be cheerfully bright. The dining room is an equally vivid crimson, also a popular color for walls in the Regency.

Sir John Soane's Museum also has gallery space for small, very selective exhibitions related to Soane's era and interests. I recommend browsing the shop on the website for museum publications. One of my favorites is The Soanes At Home: Domestic Life at Lincoln's Inn Fields, from 1997. It's full of pictures, copies of receipts and invoices and all sorts of fascinating information about life and household management in the early 19th century.

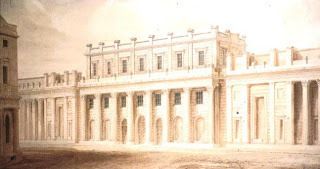

Above, Soane's drawing of the Bank of England as he rebuilt it in 1814; since then, it has been remodeled and enlarged so that little of his work is evident today, except in portions of the interior. The museum houses a collection of more than 30,000 architectural drawings by England's finest architects, as well as Soane's sketchbooks, business records and other valuable research and archival material.

Above is a drawing by J. M. Gandy of Tivoli Corner, part of Soane's Bank of England, now remodeled.

Above, a statue of Sir John Soane in the Bank of England, where he is honored even though they changed his designs beyond recognition. Soane left the buildings of his museum and his home to the nation as a resource for training future architects. It thrives today, based on contributions and resources from its special programs, events, and publications. They operate a creative and energetic educational program too. In an upcoming blog, we will visit Pitshanger Manor and the Dulwich Picture Gallery, two outstanding buildings designed by Soane and open to the public.

Published on September 24, 2011 02:00

September 21, 2011

All The Queen's Horses

From The Horse-World of London by William John Gordon (1893)

In the horse-world of London, the highest circle, the most exclusive set, so to speak, is that housed at Buckingham Palace. To many loyal subjects the Queen's horses are as much an object of interest as the regalia; and as cards of admission are freely granted by the Master of the Horse, the Royal Mews are probably the best known stables within the bills of mortality.

There are in them from ninety to a hundred horses —state horses; harness horses, coach and light; riding horses, and what not—whose forage bill runs into 30 quarters of corn, 3£ loads of hay, and 3£ loads of straw a week. Immediately to the right of the entrance gate is a stable for ten horses, mostly light and used in ordinary work; to the left is a similar stable similarly occupied. On the east side of the quadrangle are the coaches, state and semi-state, and, among others, the Jubilee landau. On the west side are more horses— sixteen or twenty of them. The state stables for the creams and blacks are on the north side, and to the left of them are housed the thirty-two splendid bays, many of them bred at the Queen's stud farm at Hampton Court; the rest bought from the dealers at prices ranging from 180L to 200L Stables there are in London of more aggressive architectural features, and some in which there is a far greater show of the very latest improvements; but there are none more well-todo looking, none in which the occupants seem more at home. Comfort and order are everywhere apparent; the grooming is, of course, perfection; and there does not even appear to be a straw out of place in the litter.

The Queen has her favourites, and in matters of horseflesh is content to leave well alone as long as possible. If a pair fetches her Majesty from Paddington, it is always the same pair; if she drives in the Park with four horses, it is always the same team; so that practically out of the hundred horses the Queen uses but six. The horses ridden by the equerries and outriders are also kept at their special work as long as they are found fit, and the visitor going the round of the stables after an interval of years, will find Blackman, and Phalanx, and Sewell, and their companions still flourishing, and seemingly more conscious than ever of the distinguished success with which they do their duty in the royal equipage of everyday life.

Of a different class altogether are the ' state horses,' which appear only on procession days, and are as much a part of the pageantry of royalty as the crown and sceptre, and other working tools of that degree. These have a stable to themselves, the 'creams' on one side, the 'blacks' on the other. The creams, like the dynasty, are of Hanoverian origin, but they have for generations been of British birth, and, like a large number of the royal horses, first breathed fresh air in the paddocks of Hampton Court. In popular superstition they represent the white horse of Hanover; but that peculiar strain died out long ago, except heraldically, and the creams were always distinct from it. Another erroneous notion, fostered, perhaps, for advertisement purposes, is that the state creams are 'cast' and find their way into circuses; but the only specimens that are ever allowed to quit the palaces go as geldings to the band of the Life Guards. With that one exception, the creams come to London when three years old, and live and are buried in the service in which they are born. Being either entire horses or mares, they require a good deal of attention; they are never left alone by day or night; and the man in charge, who has the highest post in his department, sleeps in the stable, and claims to have the longest day's work in the employment of the State.

Opposite to them are the blacks, which though, perhaps, not so graceful, are more serviceable-looking. They also are of Hanoverian origin, being essentially well-bred specimens of the better class of hearse horse, now rare amongst us owing to the preference given by our undertakers to the more sympathetically lugubrious —and cheaper—Flemish breed. They are big, splendidly showy horses, ' with a power of pride in them.'

Like the creams, they never appear on duty with unplaited manes, the blacks being decked with crimson ribbons, the creams with purple. A trifling matter this of plaiting the manes, but on trifles oft a crown doth hang. Once only did the state creams go forth unplaited. It was in 1831, when Earl Grey and Lord Brougham waited upon William IV. to recommend the immediate dissolution of the Parliament, which was playing havoc with the first Reform Bill. The scruples of the King at dissolving so young a Parliament had all been overcome, and he announced his intention of starting for the Houses forthwith, when it was pointed out that there would be no time to plait the horses' manes. 'Plait the manes!' said his Sailor Majesty, then '—with the loudest and, of course, most dignified of expletives—' I'll go in a hackney coach!' Horror of horrors! the King on such a mission in a hackney coach! And so the manes were left unplaited, and the State was saved.

But the unplaitedness disturbed many courtly minds, and Mr. Roberts, the King's coachman, above all men, was most indignant. And so it happened that a still more terrible thing took place. The horses had not been out for some time, and being harnessed in a hurry, they were, like their coachman, not in the placidest of tempers. As they passed the colour party of the Guards, the ensign, in the usual way, saluted. The creams took fright at the flash of colour, and broke into a trot. The great Mr. Roberts began to curse the soldiers loudly, and tried to check the horses in vain. On went the coach briskly. 'It was noticed,' say the contemporary historians,' that his Majesty proceeded at a faster rate than usual, in his eagerness to carry out the wishes of his people,' and, in short, he reached the Houses considerably before his time. All went smoothly enough inside, but outside there was anything but smoothness. The indignant colour-bearers appealed to their superior officers, and Mr. Roberts had to descend in double quick time from his exalted perch and humbly beg pardon for his insult to the outraged Guards. 'Swear at the King's colour, sir! Apologise instantly!' And he did. And if he had not done so, it is more than probable that the King would have had to have called that historical hackney coach for the return journey, while the nnplaited team went home, certainly Robertsless, if not coachmanless.

Neither the creams nor the blacks have had much to do of late years. Though they are the leaders of the London horse-world, their appearances are few ; but they can be occasionally found taking their exercise in pairs. The work of all the royal horses is necessarily irregular, as, though a few may be sent to Windsor, the bulk are kept continuously in London, and when the Court is away their occupation is mostly mere exercise. But when the Court is in town they have quite enough to do, work in the stables beginning at five o'clock in the morning, and sometimes, as when the German Emperor was at the palace, there is no rest until half-past two next morning. The routine is conducted with much more precision than in a private stable. Great care is taken that every turn-out is as it should be, and at every public function the carriages are paraded and inspected in the quadrangle before they are allowed to leave the stable gates.

Published on September 21, 2011 23:00

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.