Joe Blevins's Blog, page 22

April 2, 2024

Podcast Tuesday: "A Whole New Fonz"

Fonzie and the gang ride on a magic carpet with Princess Charisma.

Fonzie and the gang ride on a magic carpet with Princess Charisma.The depiction of the Middle East in popular culture has changed drastically during my lifetime. See, I grew up in the '70s and '80s. Back then, in my mind, the Middle East was a land of mystery, intrigue, adventure, and magic. A story set in Arabia would include most or all of the following elements: genies, magic lamps, turbans, scimitars, flying carpets, camels, harems, the phrase "open sesame," and lots of sexy girls in revealing outfits. And it would be set many hundreds of years ago. Beyond some palace intrigue, there would be no politics whatsoever. And outside of some vague mysticism involving magic words and crystal balls, there would be no religion either.

This was the way it was in American pop culture for years. Way back in the 1950s, for instance, Ed Wood made a short film called The Flame of Islam. Today, a film with such a title would be about the Islamic faith and would likely be the subject of great controversy. But Eddie's movie was simply a filmed burlesque show, and the term "Islam" was merely meant to suggest someplace exotic and far away.

All this started to change in the 1980s and '90s as the Middle East became more and more of a presence on the evening news. The Gulf War of 1990-91 did a lot to change American's view of the region, and subsequent Middle Eastern wars have only made the changes more profound. The Arabia of old, the land of One Thousand and One Nights, is gone from the Western imagination. Disney's Aladdin (1992) got in just under the wire. (Yes, I realize there have been sequels and a remake since then, but they don't count since they're tied to the original, well-loved movie.)

In short, we've gone from The Thief of Bagdad (1940) to The Hurt Locker (2008). Is this an improvement? I don't know, honestly. The old depictions of the Middle East had nothing to do with reality, but they had a charm of their own.

This week on These Days Are Ours: A Happy Days Podcast , we're talking about the episode "Arabian Knights." From the title onward, it's obvious that this is one of those dreamy pre-Gulf War depictions of the Middle East. But does that make it a good episode? Click the magic play button below and find out.

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on April 02, 2024 15:11

March 27, 2024

Ed Wood Wednesdays, week 181: Revisiting 'I Woke Up Early the Day I Died' (1998)

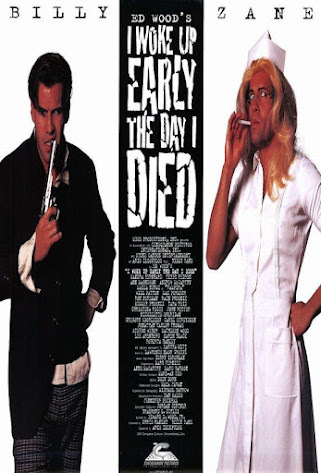

Billy Zane (in nurse uniform) leads an all-star cast in Ed Wood's I Woke Up Early the Day I Died.

Billy Zane (in nurse uniform) leads an all-star cast in Ed Wood's I Woke Up Early the Day I Died.One of the longest articles in this series—and, indeed, the history of this entire blog—is my review of Aris Iliopolus' I Woke Up Early the Day I Died (1998), a film based on a script that Ed Wood worked on for years under many titles but never managed to get produced during his own lifetime. Only after Rudolph Grey's book Nightmare of Ecstasy (1992) and Tim Burton's film Ed Wood (1994) did this long-gestating script finally see daylight, so to speak.

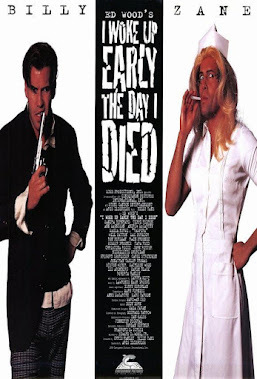

A poster for the rarely-seen film.Though it received a critical drubbing in the late '90s and never enjoyed a widespread release in America due to legal issues, I Woke Up Early remains one of the most extraordinary posthumous Ed Wood tribute films ever made. Not only does it boast higher production values than any movie Eddie ever directed, it also features performances by a gaggle of truly random celebrities, including Billy Zane, Eartha Kitt, Tippi Hedren, Karen Black, and John Ritter. The authors of The Cinematic Misadventures of Ed Wood (2015), Andrew J. Rausch and Charles E. Pratt, Jr., go so far as to call it "Edward D. Wood, Jr.'s greatest film" and lament that Eddie himself wasn't around to see it.

A poster for the rarely-seen film.Though it received a critical drubbing in the late '90s and never enjoyed a widespread release in America due to legal issues, I Woke Up Early remains one of the most extraordinary posthumous Ed Wood tribute films ever made. Not only does it boast higher production values than any movie Eddie ever directed, it also features performances by a gaggle of truly random celebrities, including Billy Zane, Eartha Kitt, Tippi Hedren, Karen Black, and John Ritter. The authors of The Cinematic Misadventures of Ed Wood (2015), Andrew J. Rausch and Charles E. Pratt, Jr., go so far as to call it "Edward D. Wood, Jr.'s greatest film" and lament that Eddie himself wasn't around to see it.When discussing I Woke Up Early the Day I Died, it's easy to focus on the film's gimmicky nature. That's what most of the reviews do, including the one I wrote ten years ago. Beyond the Ed Wood-penned script and the It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963)-style cast, there's also the fact that the story is told without dialogue in the tradition of silent movies of the 1920s and early '30s. Rausch and Pratt even freely compare it to the works of Chaplin and Keaton.

What's potentially getting lost here is the story Ed Wood wanted to tell with this film. That's why he held onto this script for years, even when getting evicted from various residences and having to ditch his other possessions. As the title character in Ed Wood, Johnny Depp even says, "All I wanna do is tell stories." So how well does Aris Iliopulos' film do that? Admittedly, I haven't spent a lot of quality time with I Woke Up Early in the last decade. But when Woodologist Angel Scott mentioned on Facebook that the film had resurfaced online, I thought it was a golden opportunity to rewatch it and see if I could look past the gimmickry and get to the heart of this material.

Admittedly, the film makes this tough to do at first. We begin with an elaborate, lengthy opening title sequence that highlights all the fabulous guest stars we're about to see. Imagine The Love Boat (1977-1987) gone punk. The credits themselves look like they were typed on a typewriter, reminding us of author Ed Wood's ghostly presence. Even after the credits, Aris Iliopulos chooses to put a scene heading ("1. INT - SANITARIUM - DUSK") on the screen, accompanied by typewriter noises. Excerpts from Wood's script appear as captions throughout the film. So the director definitely puts the gimmickry front and center. Maybe that's why we're five paragraphs into this article and I haven't even started talking about the plot or content of I Woke Up Early.

Very briefly, this film tells the story of a character known only as The Thief (Billy Zane, then at the crest of his fame), a violent madman who escapes from a sanitarium and goes on a multi-day crime spree of theft, assault, and murder in Los Angeles. Along the way, he steals $15,000 from a loan office and impulsively kills one of the employees. He puts the ill-gotten money in a briefcase that he unwisely stows in a coffin at a cemetery. The briefcase then goes missing, and The Thief spends most of the movie tracking down the people who may have taken it, all of them members of a strange Hollywood cult. His journey takes him to a variety of locations: a lighthouse, a carnival, a mortuary, a flophouse, and various bars and nightclubs. Ultimately, he winds up in the same cemetery where he originally hid the money, and there his story reaches its untimely end.

Look, this is not a naturalistic or realistic film in any way. The costumes look like costumes. The wigs look like wigs. The acting is often unsubtle. And the plot progresses in a dreamlike, surreal manner. Those expecting a conventional motion picture will be deeply frustrated by this movie. Instead, I'd say the tone of I Woke Up Early is closer to that of sketch comedy, particularly the short films you might see on, say, Saturday Night Live (1975-present) and Kids in the Hall (1988-1995). I'm particularly reminded of the "Mr. Heavyfoot" films from Kids in the Hall, since those were dialogue-free. With his continual bad luck, The Thief also reminded me of the unspeaking title character in the Pink Panther animated shorts (1969-1978) produced by DePatie-Freleng.

The point of this experiment was to see whether I could look past the film's stylistic oddness and its numerous celebrity cameos and enjoy I Woke Up Early as the story that Ed Wood wanted to tell for so many years. And, happily, I found that I could. While I'm not so sure I can agree with the authors of Cinematic Misadventures and call it Eddie's "greatest film," I'll say that this movie is the closest in spirit and tone to the breathless, often-ghoulish short stories that Ed Wood wrote in the 1960s and '70s, the ones anthologized in Blood Splatters Quickly (2014) and Angora Fever (2019). If you enjoyed those books, you'll more than likely enjoy this film.

As for the celebrity cameos, I basically stopped thinking about them after a few minutes. Earlier in this review, I compared I Woke Up Early to Stanley Kramer's Mad Mad World. That film, too, boasts an all-star cast, with all the leading, supporting, and even blink-and-you'll-miss-'em roles played by famous comedians. And yet, when I'm watching Mad World, I put that aside and get wrapped up in the story of these desperate middle-aged motorists looking for Smiler Grogan's money. I don't see the celebrities as themselves; I see them as the characters they're playing. The same basic thing happens while I'm watching I Woke Up Early. Sure, it's fun that some well-known folks from TV and film pop up throughout the running time, but it doesn't take me out of the story. If I'm giving out any best-in-show awards, I'll mention Bud Cort as a thrift store owner and Tippi Hedren as a deaf woman. Oh, and Maila "Vampira" Nurmi has a fun little scene where she does as little as possible.

Billy Zane as The Thief.A lot of the film's success as a narrative is due to the dynamic lead performance of Billy Zane as The Thief. Zane is also credited as one of the film's producers, so he clearly cared about and believed in this project, and his wholehearted commitment to the material definitely shines through in every scene. He captures not only The Thief's brutality and madness but also his utter confusion at the world (remember, he's been locked away in a sanitarium) and even his frustrations with the constant setbacks and indignities he endures along the way. It really helps that Zane looks like he could have been a movie star in the 1930s and '40s. I'd almost want to see a version of this movie that's in black-and-white with only occasional splashes of color, a la Sin City (2005).

But I wouldn't want to tamper with this movie too much, because the other great strength of I Woke Up Early is its eye-popping cinematography. Director Aris Iliopulos and cinematographer Michael Barrow give us one striking image after another, boldly using lighting, composition, and camera angles (including numerous overhead shots!) to expressionistic effect. There is nothing timid or restrained about this movie; Iliopulos goes full comic book, and it pays off. Most of the film was shot on location in various sites around Los Angeles, and it's remarkable how Iliopulos captures the seamy underbelly of the city yet manages to give it a curious glamour at the same time. It's really a shame that he never went on to make another feature film.

The key question is, would Ed Wood approve of what Aris Iliopulos did with I Woke Up Early the Day I Died? Well, he's not here to tell us, so all we can do is speculate. Eddie was certainly used to other directors filming his scripts. It happened fairly frequently from the 1950s to the 1970s: Steve Apostolof, Adrian Weiss, Don Davis, Boris Petroff, William Morgan, Ed DePriest, and more. He seemed perfectly content to hand off his work to someone else, as long as they paid him upfront, preferably in cash. Occasionally, Ed would even include phrases like "to the discretion of the director" in some of his screenplays, in case someone besides him wound up making them.

But I Woke Up Early was obviously something special to Ed Wood, not mere work-for hire like some of those other films I alluded to. He spent years on this script and held onto it as long as he possibly could. Perhaps he saw something of himself in The Thief, a desperate man without resources or even a home in Los Angeles. An outcast. A freak. A man on the run. The Thief makes the mistake of pursuing money, and it brings him nothing but grief. But what are his choices? You have to have money to survive in this world. Ed Wood knew that all too well.

Ultimately, I am confident that Ed would have been flattered by this movie. By all accounts, he was thrilled with any attention his work received, even if it were derogatory or parodic, so it would have blown his mind that a script of his went into production 20 years after his own death—with a star-studded cast, no less. Sure, he would have been bewildered by the use of Darcy Clay's snarly, aggressive "Jesus I Was Evil" over the opening credits, but the soundtrack also features more sedate fare by The Ink Spots and Nat "King" Cole, plus a sumptuous instrumental score by Larry Groupé. If nothing else, the cameos by his wife, Kathy, and his old pal, Conrad Brooks, would have warmed Eddie's drunken heart.

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 27, 2024 03:00

Ed Wood Wednesday, week 181: Revisiting 'I Woke Up Early the Day I Died' (1998)

Billy Zane (in nurse uniform) leads an all-star cast in Ed Wood's I Woke Up Early the Day I Died.

Billy Zane (in nurse uniform) leads an all-star cast in Ed Wood's I Woke Up Early the Day I Died.One of the longest articles in this series—and, indeed, the history of this entire blog—is my review of Aris Iliopolus' I Woke Up Early the Day I Died (1998), a film based on a script that Ed Wood worked on for years under many titles but never managed to get produced during his own lifetime. Only after Rudolph Grey's book Nightmare of Ecstasy (1992) and Tim Burton's film Ed Wood (1994) did this long-gestating script finally see daylight, so to speak.

A poster for the rarely-seen film.Though it received a critical drubbing in the late '90s and never enjoyed a widespread release in America due to legal issues, I Woke Up Early remains one of the most extraordinary posthumous Ed Wood tribute films ever made. Not only does it boast higher production values than any movie Eddie ever directed, it also features performances by a gaggle of truly random celebrities, including Billy Zane, Eartha Kitt, Tippi Hedren, Karen Black, and John Ritter. The authors of The Cinematic Misadventures of Ed Wood (2015), Andrew J. Rausch and Charles E. Pratt, Jr., go so far as to call it "Edward D. Wood, Jr.'s greatest film" and lament that Eddie himself wasn't around to see it.

A poster for the rarely-seen film.Though it received a critical drubbing in the late '90s and never enjoyed a widespread release in America due to legal issues, I Woke Up Early remains one of the most extraordinary posthumous Ed Wood tribute films ever made. Not only does it boast higher production values than any movie Eddie ever directed, it also features performances by a gaggle of truly random celebrities, including Billy Zane, Eartha Kitt, Tippi Hedren, Karen Black, and John Ritter. The authors of The Cinematic Misadventures of Ed Wood (2015), Andrew J. Rausch and Charles E. Pratt, Jr., go so far as to call it "Edward D. Wood, Jr.'s greatest film" and lament that Eddie himself wasn't around to see it.When discussing I Woke Up Early the Day I Died, it's easy to focus on the film's gimmicky nature. That's what most of the reviews do, including the one I wrote ten years ago. Beyond the Ed Wood-penned script and the It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963)-style cast, there's also the fact that the story is told without dialogue in the tradition of silent movies of the 1920s and early '30s. Rausch and Pratt even freely compare it to the works of Chaplin and Keaton.

What's potentially getting lost here is the story Ed Wood wanted to tell with this film. That's why he held onto this script for years, even when getting evicted from various residences and having to ditch his other possessions. As the title character in Ed Wood, Johnny Depp even says, "All I wanna do is tell stories." So how well does Aris Iliopulos' film do that? Admittedly, I haven't spent a lot of quality time with I Woke Up Early in the last decade. But when Woodologist Angel Scott mentioned on Facebook that the film had resurfaced online, I thought it was a golden opportunity to rewatch it and see if I could look past the gimmickry and get to the heart of this material.

Admittedly, the film makes this tough to do at first. We begin with an elaborate, lengthy opening title sequence that highlights all the fabulous guest stars we're about to see. Imagine The Love Boat (1977-1987) gone punk. The credits themselves look like they were typed on a typewriter, reminding us of author Ed Wood's ghostly presence. Even after the credits, Aris Iliopulos chooses to put a scene heading ("1. INT - SANITARIUM - DUSK") on the screen, accompanied by typewriter noises. Excerpts from Wood's script appear as captions throughout the film. So the director definitely puts the gimmickry front and center. Maybe that's why we're five paragraphs into this article and I haven't even started talking about the plot or content of I Woke Up Early.

Very briefly, this film tells the story of a character known only as The Thief (Billy Zane, then at the crest of his fame), a violent madman who escapes from a sanitarium and goes on a multi-day crime spree of theft, assault, and murder in Los Angeles. Along the way, he steals $15,000 from a loan office and impulsively kills one of the employees. He puts the ill-gotten money in a briefcase that he unwisely stows in a coffin at a cemetery. The briefcase then goes missing, and The Thief spends most of the movie tracking down the people who may have taken it, all of them members of a strange Hollywood cult. His journey takes him to a variety of locations: a lighthouse, a carnival, a mortuary, a flophouse, and various bars and nightclubs. Ultimately, he winds up in the same cemetery where he originally hid the money, and there his story reaches its untimely end.

Look, this is not a naturalistic or realistic film in any way. The costumes look like costumes. The wigs look like wigs. The acting is often unsubtle. And the plot progresses in a dreamlike, surreal manner. Those expecting a conventional motion picture will be deeply frustrated by this movie. Instead, I'd say the tone of I Woke Up Early is closer to that of sketch comedy, particularly the short films you might see on, say, Saturday Night Live (1975-present) and Kids in the Hall (1988-1995). I'm particularly reminded of the "Mr. Heavyfoot" films from Kids in the Hall, since those were dialogue-free. With his continual bad luck, The Thief also reminded me of the unspeaking title character in the Pink Panther animated shorts (1969-1978) produced by DePatie-Freleng.

The point of this experiment was to see whether I could look past the film's stylistic oddness and its numerous celebrity cameos and enjoy I Woke Up Early as the story that Ed Wood wanted to tell for so many years. And, happily, I found that I could. While I'm not so sure I can agree with the authors of Cinematic Misadventures and call it Eddie's "greatest film," I'll say that this movie is the closest in spirit and tone to the breathless, often-ghoulish short stories that Ed Wood wrote in the 1960s and '70s, the ones anthologized in Blood Splatters Quickly (2014) and Angora Fever (2019). If you enjoyed those books, you'll more than likely enjoy this film.

As for the celebrity cameos, I basically stopped thinking about them after a few minutes. Earlier in this review, I compared I Woke Up Early to Stanley Kramer's Mad Mad World. That film, too, boasts an all-star cast, with all the leading, supporting, and even blink-and-you'll-miss-'em roles played by famous comedians. And yet, when I'm watching Mad World, I put that aside and get wrapped up in the story of these desperate middle-aged motorists looking for Smiler Grogan's money. I don't see the celebrities as themselves; I see them as the characters they're playing. The same basic thing happens while I'm watching I Woke Up Early. Sure, it's fun that some well-known folks from TV and film pop up throughout the running time, but it doesn't take me out of the story. If I'm giving out any best-in-show awards, I'll mention Bud Cort as a thrift store owner and Tippi Hedren as a deaf woman. Oh, and Maila "Vampira" Nurmi has a fun little scene where she does as little as possible.

Billy Zane as The Thief.A lot of the film's success as a narrative is due to the dynamic lead performance of Billy Zane as The Thief. Zane is also credited as one of the film's producers, so he clearly cared about and believed in this project, and his wholehearted commitment to the material definitely shines through in every scene. He captures not only The Thief's brutality and madness but also his utter confusion at the world (remember, he's been locked away in a sanitarium) and even his frustrations with the constant setbacks and indignities he endures along the way. It really helps that Zane looks like he could have been a movie star in the 1930s and '40s. I'd almost want to see a version of this movie that's in black-and-white with only occasional splashes of color, a la Sin City (2005).

But I wouldn't want to tamper with this movie too much, because the other great strength of I Woke Up Early is its eye-popping cinematography. Director Aris Iliopulos and cinematographer Michael Barrow give us one striking image after another, boldly using lighting, composition, and camera angles (including numerous overhead shots!) to expressionistic effect. There is nothing timid or restrained about this movie; Iliopulos goes full comic book, and it pays off. Most of the film was shot on location in various sites around Los Angeles, and it's remarkable how Iliopulos captures the seamy underbelly of the city yet manages to give it a curious glamour at the same time. It's really a shame that he never went on to make another feature film.

The key question is, would Ed Wood approve of what Aris Iliopulos did with I Woke Up Early the Day I Died? Well, he's not here to tell us, so all we can do is speculate. Eddie was certainly used to other directors filming his scripts. It happened fairly frequently from the 1950s to the 1970s: Steve Apostolof, Adrian Weiss, Don Davis, Boris Petroff, William Morgan, Ed DePriest, and more. He seemed perfectly content to hand off his work to someone else, as long as they paid him upfront, preferably in cash. Occasionally, Ed would even include phrases like "to the discretion of the director" in some of his screenplays, in case someone besides him wound up making them.

But I Woke Up Early was obviously something special to Ed Wood, not mere work-for hire like some of those other films I alluded to. He spent years on this script and held onto it as long as he possibly could. Perhaps he saw something of himself in The Thief, a desperate man without resources or even a home in Los Angeles. An outcast. A freak. A man on the run. The Thief makes the mistake of pursuing money, and it brings him nothing but grief. But what are his choices? You have to have money to survive in this world. Ed Wood knew that all too well.

Ultimately, I am confident that Ed would have been flattered by this movie. By all accounts, he was thrilled with any attention his work received, even if it were derogatory or parodic, so it would have blown his mind that a script of his went into production 20 years after his own death—with a star-studded cast, no less. Sure, he would have been bewildered by the use of Darcy Clay's snarly, aggressive "Jesus I Was Evil" over the opening credits, but the soundtrack also features more sedate fare by The Ink Spots and Nat "King" Cole, plus a sumptuous instrumental score by Larry Groupé. If nothing else, the cameos by his wife, Kathy, and his old pal, Conrad Brooks, would have warmed Eddie's drunken heart.

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 27, 2024 03:00

March 20, 2024

Ed Wood Wednesdays, week 180: Lee Kolima, Hawaii's answer to Tor Johnson

No, that's not Tor Johnson. It's Lee Kolima.

No, that's not Tor Johnson. It's Lee Kolima.Ed Wood follows me everywhere. It's true. Eddie's career has become the prism through which I see the rest of the world. Whether I'm watching a movie, reading a book, or just scrolling through internet videos, I'm always looking for connections to the weird, wacky world of Wood. That's what you get when you do a series called Ed Wood Wednesdays for more than a decade.

Just this week, for instance, I saw a clip from The Joe Rogan Experience in which British scientist Matthew Walker describes the effects of alcoholism on sleeping and dreaming. According to Walker, alcohol blocks the dream sleep (or REM sleep) that the brain craves and demands. Eventually, chronic alcoholics will begin to dream while they're awake. "It's this collision of two states of consciousness," Walker says. I've often described Ed Wood's writing as dreamlike, and I naturally wondered if this were a result of his severe alcoholism. Certainly something to think about.

Lee Kolima as Bobo on Get Smart.But there are less serious examples, too. Yesterday, I was watching a September 1965 episode of Get Smart called

"Diplomat's Daughter"

when I saw something that amazed me. The episode's villain, The Claw (Leonard Strong), had a bald, hulking henchman named Bobo who was nearly identical to the character of Lobo played by Tor Johnson in Ed Wood's Bride of the Monster (1955) and Night of the Ghouls (1959), plus The Unearthly (1957), directed by Wood associate Boris Petroff.

Lee Kolima as Bobo on Get Smart.But there are less serious examples, too. Yesterday, I was watching a September 1965 episode of Get Smart called

"Diplomat's Daughter"

when I saw something that amazed me. The episode's villain, The Claw (Leonard Strong), had a bald, hulking henchman named Bobo who was nearly identical to the character of Lobo played by Tor Johnson in Ed Wood's Bride of the Monster (1955) and Night of the Ghouls (1959), plus The Unearthly (1957), directed by Wood associate Boris Petroff. The names Lobo and Bobo were too close to each other to be a coincidence. However, I knew that Tor Johnson had never guested on Get Smart and had basically retired from show business after his starring role in Coleman Francis' The Beast from Yucca Flats (1961). So who was this extremely Tor-like guy playing Bobo opposite Don Adams? (In fact, Bobo appeared twice on Get Smart; he was brought back later in the first season for "The Amazing Harry Hoo.")

The answer is Lee Kolima (1920-1995), a Hawaiian-born actor who worked in film and television for nearly twenty years and appeared alongside some very famous people in the process. Like Tor Johnson, Lee was a wrestler , having used such names as Great Toto, Kubla Khan, and Royal Hawaiian during his career. His real name, though, was Charles Howard Zalopany, and he was born on November 20, 1920 in Honolulu, meaning that he was already well into his 40s when he started acting. Young Charles grew up in a rather large family; historical records show he had at least five siblings.

His late start as an actor didn't hamper him. Hollywood is always going to need big, tough-looking dudes to act as thugs, guards, and assorted bad guys. Some might attribute Lee Kolima's career to the James Bond spy craze that captured all of popular culture in the 1960s. Too bad Tor Johnson's career was already over by the time the fad started; he could have made some serious meatball money in the 1960s. As it was, the younger Lee Kolima scooped up roles on such action shows as Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, I Spy, The Girl from U.N.C.L.E., Garrison's Gorillas, and The Wild Wild West, plus the movies 7 Women (1965), Dimension 5 (1966), and The King's Pirate (1967).

For such a colorful and unusual actor, Lee Kolima's career is shockingly under-documented. In fact, I could find no articles about the man whatsoever—no interviews, no career retrospectives, nothing. His wrestling career is even more obscure than his movie career. I found only a few fleeting references to his matches in newspaper articles from the early 1950s, nearly all from California. An online archive says he had 145 bouts, stood 6'3", and weighed 280 pounds. That makes him the same height as Tor Johnson but 120 pounds lighter. Indeed, he looks more svelte than Tor and moves more easily onscreen. But directors didn't trust either man with much dialogue.

If Lee's famous for anything in particular, it's for his association with that loveable prefabricated pop group, The Monkees. For a while there, Lee was practically the fifth Monkee. He guested twice on their self-titled TV show, appearing as Yakimoto in "The Spy Who Came in from the Cool" in Season 1 and as Attila the Hun (!) in "The Devil and Peter Tork" in Season 2. Lee even turned up as a guard in The Monkees' trippy feature film Head (1968). I've seen rumors on the internet suggesting this is Tor Johnson, but the evidence indicates it was Lee.

The Monkees wasn't Lee's only foray into comedy, by the way. In the late '60s and early '70s, he also appeared on The Red Skelton Show and The Jonathan Winters Show, plus the sitcom That's My Mama. Miraculously, his application to join AFTRA has survived from this era in his career. Notice that this document includes both his stage name and his real name. We can also see that he was living at 16246 Virginia Ave. in Paramount, CA. There's still a charming two-bedroom home with Spanish tiles on the roof at this location.

Lee gets into the union.

Lee gets into the union.The wrestler's career naturally slowed down in the 1970s and '80s as he began to age. As an actor, Lee last turned up onscreen in the notorious Burt Reynolds vehicle Cannonball Run II (1984). But his most lasting contribution to pop culture during the Reagan years was modeling for the cover of Tom Waits' classic album Swordfishtrombones (1983), where he appeared alongside Waits himself and dwarf actor Angelo Rossitto, whom we have discussed previously . All three men look like circus performers here, reminding me of the cover of Strange Days by The Doors (1967). Notice how both albums include a strongman and a dwarf, while Waits' own heavy makeup resembles that of the mime on the Strange Days cover. Just a theory.

Lee Kolima (left) with Angelo Rossitto and Tom Waits on the cover of Swordfishtrombones.

Lee Kolima (left) with Angelo Rossitto and Tom Waits on the cover of Swordfishtrombones.Lee Kolima died at the age of 75 in November 1995, just a year after George "The Animal" Steele portrayed Tor Johnson in Ed Wood (1994). Lee's death generated no publicity. I cannot even find an obituary for the man, nor any record of how or where he was buried. But the TV shows and movies in which Lee appeared will likely be in circulation for decades to come, and I probably won't be the last to spot him somewhere and think, "Hey, isn't that Tor Johnson?"

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 20, 2024 03:00

March 19, 2024

Podcast Tuesday: "2057: A Fonz Odyssey"

Fonzie (Henry Winkler) is torn between a robot and a future chick on Fonz and the Happy Days Gang.

Fonzie (Henry Winkler) is torn between a robot and a future chick on Fonz and the Happy Days Gang.In 1977, Happy Days producer Garry Marshall asked his young son, Scotty, why he no longer watched his father's own, highly-rated sitcom. The boy, then obsessed with Star Wars (1977), answered that the show didn't have space in it. The result was the classic February 1978 episode "My Favorite Orkan," in which Fonzie (Henry Winkler), Richie (Ron Howard), and the gang encounter manic, fast-talking alien Mork from Ork (Robin Wiliams). The character of Mork proved so popular, he got a successful spinoff of his own.

Fun as it is, "My Favorite Orkan" isn't much like Star Wars. It takes place entirely on Earth, and the action is limited to the usual, workaday Happy Days locations: the Cunninghams' tidy suburban home and Arnold's drive-in restaurant. Mork himself, wild though his personality may be, just looks like a human being in a red jumpsuit. There are no robots, space ships, or laser guns in it. And, depending on which version of the episode you watch, the whole thing could just be a dream. History does not record Scotty Marshall's reaction to "My Favorite Orkan." I wonder if he found it satisfying.

I think the "space" version of Happy Days that Scotty was envisioning was a lot more like "May the Farce be with You," an episode of The Fonz and the Happy Days Gang that aired in November 1980. From its title onward, this is much, much closer to Star Wars. It's teeming with robots and star jets, and the entire thing takes place in outer space in the year 2057, which must have sounded a lot further off back then. The plot has Fonzie and his pals foiling the plans of some evil androids to blow up the Earth. Doesn't that sound like fun?

Find out if it is by listening to the latest episode of These Days Are Ours: A Happy Days Podcast .

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 19, 2024 14:03

March 13, 2024

The strange but true saga of the 'What's My Line' intruder (updated for 2024!)

This pleasant young man somehow wandered onto the set of What's My Line.

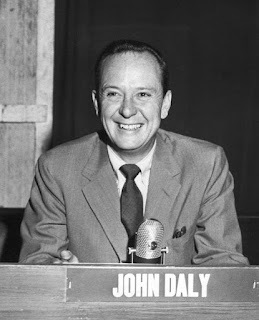

This pleasant young man somehow wandered onto the set of What's My Line. Game show host John Charles DalyThe appeal of live television has always been the possibility that something might go seriously wrong on the air in front of an audience of millions. Much of what we see on TV is carefully planned, rehearsed, and edited before it ever reaches us. It's no wonder, then, that we hunger for a little chaos amid all that control. Let's face it, this is the main justification for Saturday Night Live's continued existence. The long-running comedy-variety series could easily be pretaped, but it would lose its sense of danger and spontaneity.

Game show host John Charles DalyThe appeal of live television has always been the possibility that something might go seriously wrong on the air in front of an audience of millions. Much of what we see on TV is carefully planned, rehearsed, and edited before it ever reaches us. It's no wonder, then, that we hunger for a little chaos amid all that control. Let's face it, this is the main justification for Saturday Night Live's continued existence. The long-running comedy-variety series could easily be pretaped, but it would lose its sense of danger and spontaneity.We hunger for an element of risk in our entertainment. I can't help but think about Dave Chappelle's stand-up routine in which he discusses the infamous night in 2003 when magician Roy Horn was attacked by a tiger during a show in Las Vegas. "That's why we really go to the tiger show, right?" Chappelle says to the audience. "You don't go to see somebody be safe with tigers."

These days, pretaped shows are the norm and live broadcasts are considered special events. This was not so in the earliest days of the medium in the 1940s, when virtually everything on TV went out over the airwaves as it was being made and relatively little was saved for posterity via crude kinescopes. A major change arrived in 1951, when Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz had the foresight to film their sitcom I Love Lucy on 35mm stock, thus ensuring the episodes would be preserved for future reruns.

Over the course of the 1950s, videotape technology improved and became more common in the industry, allowing shows to be shot in advance and edited. This was seen as a potential breakthrough for the medium. On his 1957 record "Tele-Vee-Shun," satirist (and stubborn TV skeptic) Stan Freberg begrudgingly admitted that "videotape may help somewhat." Freberg himself had been a puppeteer on the children's show Time for Beany (1949-1955) and had learned about the hazards of live television when he'd burned his hand during a sketch involving a clown. On a DVD commentary, Freberg recalled that the clown puppet made "a fast exit" from the scene after catching on fire.

By the 1960s, many shows were being filmed or taped in advance, but the venerable panel show What's My Line (1950-1967) was still being broadcast live every week from the CBS studio in New York City. Produced by Mark Goodson and Bill Todman, What's My Line is the kind of stately, old-fashioned program that seems inconceivable to modern day audiences. The premise is very simple. The host introduces a contestant with an unusual occupation, and then four celebrity panelists—generally culled from the theater and publishing worlds—try to determine that occupation (or "line") via a series of yes/no questions. ("Do you work with animals?") The contestant's goal is to stump the panel for as long as possible.

For me, the highlight of each What's My Line episode is the appearance of a celebrity "mystery guest." During this round, the panelists wear blindfolds and attempt to guess the identity of the famous person, again through yes/no questions. ("Are you known for your work in the theater?") This is an exceedingly polite and genteel program, making it truly seem like a relic from a bygone age. The show's stuffiness is now, at least to me, its chief selling point. var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 13, 2024 16:24

Ed Wood Wednesdays: The Transmutation of Jeron Charles Criswell King, Part 2 1940-1947 (Guest Author: James Pontolillo)

This week, James further explores the life and career of Criswell.

This week, James further explores the life and career of Criswell.

"Like other skeptics, I once made the mistake of underrating the cold readers."William Lindsay Gresham, Monster Midway

Note: The search for information about Jeron Charles Criswell King is complicated by the multiple names that he employed up through at least the age of 40. He variously used Charles Criswell, Charles Criswell King and C.C. King as his legal name, while using Charles Cris King, Jeron Criswell, J. K. Criswell, King Criswell, and simply Criswell as stage names (along with the dubious titles of Doctor and Reverend). Similarly, his wife Myrtle Louise Stonesifer used Louise Howard, Halo Meadows, and Halo Vanessa as stage names. I will simply refer to them as Criswell and Louise.

The dawn of the 20th century found Hollywood a quiet place of orchards, farm fields, and scattered homes [1, 2] . A decade later, Hollywood Boulevard had been transformed into a wealthy residential street of stately mansions and impressively manicured yards [3 , 4, 5] . The early 1920s saw the arrival of the film industry with a large number of movie studios, theaters, and shopping centers along Hollywood and Sunset Boulevards [6, 7] . The legion of workers needed to support the rapidly expanding industry drove an ever-growing need for dense residential development. By 1930 rural Hollywood and most of the stately mansions were a distant memory – replaced by bungalow courts, duplexes, and multi‐story apartment buildings [8] . Hollywood was not unique in this regard but mirrored development throughout the region. From 1900 to 1940, the population of Los Angeles skyrocketed from 103,000 to 1.5 million as it progressed from being the 36th to the 4th largest city in the nation.

The new arrivals brought with them an unprecedented diversity of beliefs reflective of a trend away from traditional religion that had been spreading across America since the mid-1800s. Among the new faiths to be found in Los Angeles were charismatic and esoteric Christian sects, spiritualism, New Thought ministries, Theosophy with its national headquarters [9] , Guy Ballard's I Am Movement, ceremonial magic orders such as the Golden Dawn and Ordo Templi Orientis, as well as a host of lesser occult and metaphysical lights. The film industry, with its seductive subtext that all things are possible, multiplied the effect by attracting individuals dissatisfied with tradition and seeking to create a new life on the West Coast. Newspaper reports revealed 1930s Los Angeles to be "a seething mass of spiritual guides, mystics, fortune tellers, palm readers, and invented sects, with classified ads promising answers for seekers of love, fortune, a salve to their pain, or the access to a higher truth." Many movie stars immersed themselves in metaphysical practices and paid seers handsomely to warn them of astrological changes that might adversely affect their careers.

The reaction by Los Angeles officialdom to this increasingly influential subculture was anything but positive. Newspapers warned readers of charlatanry run amuck with cautionary tales of crooked gypsies and mediums [10] . City leaders suggested that fortune tellers should have to publicly demonstrate their powers or lose their licenses. Police investigated criminal gangs of psychics who extorted, blackmailed, and even sexually assaulted their followers. To the cynic, Los Angeles had become a "haven for psychopaths and confidence-workers of every stripe and degree… Its most elaborate commercial structures are mortuaries… the native Angeleno, who qualifies for such after a six-month residence, is a superior braggart, annoyingly boastful over what turns out to be nonexistent."

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 13, 2024 03:00

March 6, 2024

Ed Wood Wednesdays: The Transmutation of Jeron Charles Criswell King, Part 1 1926-1939 (Guest Author: James Pontolillo)

This week, James Pontolillo gives us a glimpse at the early years of Plan 9 star Criswell.

This week, James Pontolillo gives us a glimpse at the early years of Plan 9 star Criswell."You know, kid… lad like you could be a great mentalist. Study human nature."William Lindsay Gresham, Nightmare Alley

Note: The search for information about Jeron Charles Criswell King is complicated by the multiple names that he employed up to the age of 40. He variously used Charles Criswell, Charles Criswell King and C.C. King as his legal name, while using Charles Cris King, Jeron Criswell, J. K. Criswell, King Criswell, and simply Criswell as stage names (along with the dubious titles of Doctor and Reverend). I will simply refer to him as Criswell. It is often claimed that his surname is actually Konig. There is no evidence to support this assertion. Criswell's surname traces back unchanged to his earliest known ancestor, Samuel King (1775 Virginia).

The publication of Edwin Lee Canfield's Fact, Fictions, and the Forbidden Predictions of the Amazing Criswell (2023) has finally provided fans with an abundance of material on the quirky psychic and key Ed Wood repertory player. Canfield corrected a long-standing problem where Criswell was concerned – a lack of basic information and leads to pursue. Nearly all online biographies about Criswell are short and riddled with errors. The man himself provided few clues beyond brief disjointed statements scattered across interviews, magazine articles, and the introductions to his prophetic books. These statements are generally unreliable in their details. If Ed Wood, Jr. was a bullshitter about certain aspects of his life, then Criswell by comparison would have to be called The Amazing Bullshitter.

One particular claim that Canfield reproduced caught my attention: that for two summers Criswell served as a manager/actor at Greenkill Park Theater outside of Kingston, NY. If true, this placed him a mere 19 miles from Ed Wood, Jr. Was it possible that young Eddie had seen Criswell perform on stage with neither man being aware of this connection when they met up yet again years later in Hollywood? I immediately began a deep dive in search of confirmation. Uncovering many previously unreported details on Criswell's life, I realized that there was a much larger story to be told. The story of the unlikely transmutation of a rural Indiana high school boy into the Amazing Criswell.

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 06, 2024 03:00

March 5, 2024

Podcast Tuesday: "Cavemen and Dinosaurs Living Together! Mass Hysteria!"

Fonzie and cavewoman Bruta on The Fonz and the Happy Days Gang.

Fonzie and cavewoman Bruta on The Fonz and the Happy Days Gang.It's me, okay? I wasn't ready to let the Happy Days podcast go. I had to keep it going somehow! So now, my poor cohost has been wrangled into reviewing the animated spinoff The Fonz and the Happy Days Gang episode by episode. Don't feel too bad. This entire podcast was my cohost's idea in the first place. Now it's become sort of like a Chinese finger trap. The more you try to escape, the more it clings to you.

My memories of TFATHDG are vague at best. I do remember watching this very goofy Hanna-Barbera show when it was new in the early 1980s and being excited that both Richie (Ron Howard) and Ralph (Don Most) were on it, since they'd just left the live-action Happy Days. The focus here is obviously on Fonzie (Henry Winkler), who gets to be more like he was in the early days of the sitcom, i.e. impossibly cool, irresistible to women, and seemingly in possession of magical powers. The cast is rounded out by a ditzy "future chick" named Cupcake (Didi Conn from Grease) and Fonzie's irritating dog, Mr. Cool (animation legend Frank Welker). All these characters are bouncing around through history in a time machine that looks suspiciously like a flying saucer.

This week on These Days Are Ours: A Happy Days Podcast , we review what is essentially the pilot for the animated series, the prehistoric adventure "King for a Day." I say "essentially" because this barely qualifies as a pilot. The theme song (narrated by Wolfman Jack) sets up the premise of the show, but there is no further explanation for why Fonzie and pals are traveling through time in a spaceship. They just are, and we have to be fine with that.

Were we fine with that? Find out by listening to our latest podcast below.

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on March 05, 2024 14:11

February 28, 2024

Ed Wood Wednesdays, week 179: The Perverts (1968) [PART 2 of 2]

An unusual massage from Ed Wood's The Perverts. (Image courtesy of Bob Blackburn.)

An unusual massage from Ed Wood's The Perverts. (Image courtesy of Bob Blackburn.)Let's play a game.

I'll give you a passage from The Perverts (1968), a sexual guidebook Ed Wood wrote for Viceroy under the assumed name "Jason Nichols," and you try to tell me what this chapter is actually about. Ready? Here goes:

Time and the tide seldom changes. It only revamps itself to progress other thoughts. The river continues to run year after year and one might wonder why it never runs dry. The story is that the river is once more sucked up into the sun and redeposited at the head again.Okay, maybe that wasn't enough. I'll give you the entire next paragraph:

Sex is much the same way. As has been stated over and over again during these chapters, SEX per se is never satisfied. It is only sucked up into the body of another and redeposited for another fling, and so it shall be to the end of time and since there is no such thing as the end of time so there shall never be an end to SEX and the variations thereof.Give up? That was from the chapter about incest. So what was all that stuff about tides and rivers and the sun? You got me. But I'm trying to give you an idea of what reading The Perverts is like.

As a writer with a restless mind, Ed Wood will go off on philosophical tangents that have little or nothing to do with the subject at hand. Remember Glen or Glenda (1953), in which narrator Dr. Alton (Timothy Farrell) is supposed to be telling us about cross-dressers but somehow gets onto the topic of "the modern world and its business administration"? Much of The Perverts is like that. The book's quasi-lofty tone is also highly reminiscent of the ponderous narration of Ed's The Young Marrieds (1972). Very often in that film, the narration will play over footage of waves crashing against the rocks, similar to the tidal imagery used in The Perverts.

Speaking of images, last week I complained that my edition of the book lacked the photos that were in the original printing. Well, Bob Blackburn heard my plea and sent me some of the pics from his copy of The Perverts, which in turn was Ed Wood's own personal copy of the book! Bob says that there are about 20 to 30 "mostly topless" black-and-white photographs altogether in his edition. It does not look like the publisher, Viceroy, commissioned new photos based specifically on Ed Wood's text, but instead used whatever photos they happened to have lying around that sort of matched what was in the book. Below is a collage of images from the chapters on troilism, fetishes, and lesbianism.

A triptych of images from The Perverts.

A triptych of images from The Perverts.I'm grateful to Bob for giving me a sampling of the visual content in The Perverts. Feel free to explore this gallery of images if you're interested in seeing more. But now, let us talk about the literary content in this remarkable book.

var infolinks_pid = 3415273; var infolinks_wsid = 0;

Published on February 28, 2024 03:00