Gary M. Nelson's Blog, page 5

August 8, 2012

Built to Last: Forget Waterfall, Forget Agile - Let's Talk Tectonic Project Methodologies

[Also available as a podcast]

Have you ever managed a really big project? I am certain that many of you have managed some very large projects. But how big is that, exactly? As big as the pyramids? Well, maybe some of you have. But there are some projects that make even those pale in comparison.

As a matter of fact, I am currently sitting in the middle of one of the world's largest Projects. No, it was not my project - not by a long shot. We don't actually have the email or mobile number for the project manager responsible - but you can clearly see the results.

I am sitting here typing away in Hamilton - roughly in the middle of the North Island of New Zealand.

No, Hamilton is bigger than a pyramid, but it is not the project either. It is a nice place to live, and a medium sized city for New Zealand - actually the largest inland city as the main ones are along one coast or another.

The project of which I am speaking is the whole of the North Island itself. The island is 113,729 square kilometres (43,911 sq mi) in area, making it the world's 14th-largest island.

Ok, ok, you say - what's the point, and how is this a project?

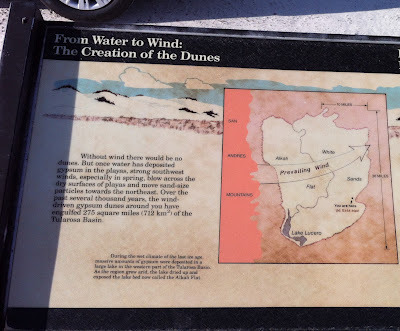

I suggest this is a project because it is almost entirely volcanic in origin. Just like Hawaii or any of the smaller pacific islands - but on a much, much larger scale - both geographically and the project timeline.

I guess we should really call it a Program, because it is so large. Ok then, it's a very large program - with each of the volcanoes an individual project. 27 major volcanoes in the Taupo Volcanic zone itself, with another 15 or so scattered in the North Island - well, much more than that because the Auckland Volcanic Field features more than 60 cones. After a while, you lose count of the smaller volcanoes.

Then there is the South Island - a very different kind of project and island.

So - let's translate this to Project Management terms - and build ourselves an island or two.

Making an IslandWhy the sudden interest in geology? August 6, 2012, 23:50 - Mt Tongariro erupted for the first time since 1897. Mt Tongariro is a large volcano just to the south of Lake Taupo. It has several nearby sister volcanoes, Mt Ngarahoe, which last erupted in 1977 and is technically a vent on Mt Tongariro, and Mt Ruapehu, an impressive volcano with several major ski fields which last erupted in 1995-1996. And of course, Lake Taupo itself (616 square km / 238 square miles) is in the crater of New Zealand's largest volcano.

Mt Ruapehu and Ngarahoe (right), Taupo Volcanic Zone

Mt Ruapehu and Ngarahoe (right), Taupo Volcanic Zone

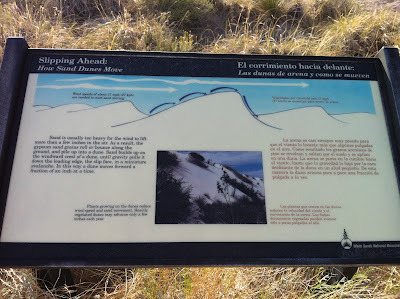

Growing an island by volcano is a much different activity than slamming tectonic plates together and uplifting a new mountain range - a process called thrust faulting, where the shock wave of the plate collision forces huge masses of rock to crack and slide up over its neighbour. This is how the South Island, the Rockies and all major mountain ranges formed.

The other way - one might even say a more elegant way - to grow an island is slowly, progressively, from the bottom up like the North Island. Layer upon layer, the volcanic cones rise from magma vents in the ocean floor until they break through the surface of the water - a noisy birth with lots of steam and splashing. Most of the Pacific Islands formed this way, and the peak is just the tip of a very tall volcanic cone rising from the sea floor. Some quit shortly after they broke through the water - forming a lot of the smaller islands, while others continued to grow and form mountains and valleys in between.

Comparing Tectonic Project MethodologiesOk, so we have two main methods to choose from to build your island and raise it up above the waterline, or increase its height.

Thrust Fault (convergent plate movement)Volcanic (convergent or divergent plate movement)Both processes occur due to changes at plate boundaries, and you may even have volcanic activity around the edges of a thrust fault, depending on any weak points (hot spots) created along the underlying plate.

But enough geology - how does this apply to projects? Both have the same eventual goal - to create an island where once there was water. Let's look at the differences in approach - and the lessons we can learn when applied to our projects.

Thrust Fault ProjectsSome projects have a lot of things thrust together by force to produce a project outcome - often with major clashes and collisions between stakeholders and the project team as well. And although the results can be breathtaking when you look at it later, it is certainly disruptive while the building-up part is going on. Car wrecks are sudden, spectacular and breathtaking too - just not very healthy for the stakeholders.

The main feature about this methodology is the use of sudden change to complete the project after a long quiet buildup. With little or no warning, there is a flurry of activity, a lot of energy expended, and suddenly it is over and things will never be the same again.

One of the problems with this approach from a people perspective is that sudden, unexpected change tends to cause resentment and feelings of loss to those affected. This may be the users of the old system, or a person whose house was flattened by the Richter 9.5 triggered by the nearby hill's ambition to suddenly become a mountain. In both cases, you have ripped out the foundations from underneath people with no warning or preparation - in other words, there was no Change Management Plan . Put simply, there was not a lot of communication about what was coming, period.

One minute, you and all your fishy buddies are swimming away close to the shoreline, and then - BAM!- you are high and dry and upwardly mobile. No change management plan for you - learn to walk and breathe air, or die. Not everyone survives this type of project.

In real life, an event like this results in a major earthquake - and it is usually not the last. There is almost always an adjustment period, as things settle into place - accompanied by a rash of smaller earthquakes over time. Expect the same things on your Thrust Fault projects - when you suddenly change or impose things on your users, there will be a lot of adjusting, support and probably apologizing to do before they settle in to the new way of things.

Project Change Requests in this type of project are rarely uneventful.

And like the vertical adjustment to Mt Cook a couple years back, where a huge chunk of rock slid off the peak down into the valley, not everyone will want to stay on after the thrust fault event, but they might not leave right away. Just don't be surprised when they do leave.

Of course, not all Thrust-Fault projects are bad news. If you are launching a new product or a rocket to the stars, you will necessarily have your major event at the end. There will be a lot riding on the outcome, and a lot of internal activity leading up to it - but it is not as visible as the actual public launch.

Volcanic ProjectsVolcanoes get a bad rap. Compared to the energies and destruction caused by raising a thrust-fault mountain range, volcanoes are positively gentle. When they are first forming, you have plenty of warning that they are coming - gas venting, steam, warming of the water. Once they clear the water, they even provide you with night-lights to stay clear as the red-hot magma flows down the mountain side. If it thinks you are getting to close for your own safety, it may blow off some steam or ash. They are playful too - they may toss you a few pyroclastic boulders. (I don't recommend you do the "catching" part though). Sometimes you even get a free fireworks display.

Sure, they can cause destruction and changes to the terrain, but aside from ash clouds there are limited effects far from the volcano. Lava flows downhill, boulders can only be tossed so far. I am not downplaying ash clouds though - they can be very disruptive to the areas coated with ash - nearby and far afield, and they are a threat to aircraft. However this is a matter of perspective. None of us have seen a mountain range suddenly thrust out out of the earth beneath you. Volcanic eruptions are much more common in comparison. It is unlikely you would survive a mountain-building thrust fault event near you - you have a much higher chance of survival being near a volcano, as bad as it may seem.

The main feature about this methodology that makes it preferable on most projects is that while you are building your volcano, it is a gradual process. You have plenty of time to communicate with those affected and utilize a Change Management Plan as you build up towards the project goals, layer by layer. Sure, there will be some excitement and fireworks, but most of the growth in your project will be like the layering of magma as the volcano grows taller. While magma is flowing, the Volcano is actually relatively happy - there is a steady release of pressure without excessive build-ups. It is only when you run into obstacles and blockages that you have a danger of outbursts or violent eruptions. But again - you have the element of time. It takes many years to grow a volcano, so even though there seems to be bursts of short-term activity, the overall progress is relatively steady.

The one trick with volcanoes, of course, is the Project Change Requests. With a Thrust Fault project, you know to expect a flurry of these after the main event, and then things will tail off. With the Volcanic Project, things may seem to be quiet for a long period and then you may have an unexpected eruption of post-build activity.

Not a problem, really - unless you decided to build your house on the side of the volcano because of the nice view.

SummarySo what kind of project are you on? Thrust-Fault or Volcano? The needs of your project will generally dictate which approach is best.

If your project outcome is necessarily a sudden cut-over or launch type event, you might need to use Thrust-Fault. (Just do as much as you can on the communication side of things)If your project outcome affects a lot of people, it is usually best to use the Volcano approach when you can - build up slowly, and employ your Change Management Plan liberally.

The key is to keep an eye on how your project is turning out - if you planned for a Volcano, watch that you don't end up with a Thrust-Fault because you stopped communicating. It makes for a strangely shaped deliverable.

Good luck with your projects, and if you get a chance, come on "down under" to visit New Zealand. You will see an amazing variety of geology and scenery if you do!

Gary Nelson, PMP

Gazza Consulting Services

Have you ever managed a really big project? I am certain that many of you have managed some very large projects. But how big is that, exactly? As big as the pyramids? Well, maybe some of you have. But there are some projects that make even those pale in comparison.

As a matter of fact, I am currently sitting in the middle of one of the world's largest Projects. No, it was not my project - not by a long shot. We don't actually have the email or mobile number for the project manager responsible - but you can clearly see the results.

I am sitting here typing away in Hamilton - roughly in the middle of the North Island of New Zealand.

No, Hamilton is bigger than a pyramid, but it is not the project either. It is a nice place to live, and a medium sized city for New Zealand - actually the largest inland city as the main ones are along one coast or another.

The project of which I am speaking is the whole of the North Island itself. The island is 113,729 square kilometres (43,911 sq mi) in area, making it the world's 14th-largest island.

Ok, ok, you say - what's the point, and how is this a project?

I suggest this is a project because it is almost entirely volcanic in origin. Just like Hawaii or any of the smaller pacific islands - but on a much, much larger scale - both geographically and the project timeline.

I guess we should really call it a Program, because it is so large. Ok then, it's a very large program - with each of the volcanoes an individual project. 27 major volcanoes in the Taupo Volcanic zone itself, with another 15 or so scattered in the North Island - well, much more than that because the Auckland Volcanic Field features more than 60 cones. After a while, you lose count of the smaller volcanoes.

Then there is the South Island - a very different kind of project and island.

So - let's translate this to Project Management terms - and build ourselves an island or two.

Making an IslandWhy the sudden interest in geology? August 6, 2012, 23:50 - Mt Tongariro erupted for the first time since 1897. Mt Tongariro is a large volcano just to the south of Lake Taupo. It has several nearby sister volcanoes, Mt Ngarahoe, which last erupted in 1977 and is technically a vent on Mt Tongariro, and Mt Ruapehu, an impressive volcano with several major ski fields which last erupted in 1995-1996. And of course, Lake Taupo itself (616 square km / 238 square miles) is in the crater of New Zealand's largest volcano.

Mt Ruapehu and Ngarahoe (right), Taupo Volcanic Zone

Mt Ruapehu and Ngarahoe (right), Taupo Volcanic ZoneGrowing an island by volcano is a much different activity than slamming tectonic plates together and uplifting a new mountain range - a process called thrust faulting, where the shock wave of the plate collision forces huge masses of rock to crack and slide up over its neighbour. This is how the South Island, the Rockies and all major mountain ranges formed.

The other way - one might even say a more elegant way - to grow an island is slowly, progressively, from the bottom up like the North Island. Layer upon layer, the volcanic cones rise from magma vents in the ocean floor until they break through the surface of the water - a noisy birth with lots of steam and splashing. Most of the Pacific Islands formed this way, and the peak is just the tip of a very tall volcanic cone rising from the sea floor. Some quit shortly after they broke through the water - forming a lot of the smaller islands, while others continued to grow and form mountains and valleys in between.

Comparing Tectonic Project MethodologiesOk, so we have two main methods to choose from to build your island and raise it up above the waterline, or increase its height.

Thrust Fault (convergent plate movement)Volcanic (convergent or divergent plate movement)Both processes occur due to changes at plate boundaries, and you may even have volcanic activity around the edges of a thrust fault, depending on any weak points (hot spots) created along the underlying plate.

But enough geology - how does this apply to projects? Both have the same eventual goal - to create an island where once there was water. Let's look at the differences in approach - and the lessons we can learn when applied to our projects.

Thrust Fault ProjectsSome projects have a lot of things thrust together by force to produce a project outcome - often with major clashes and collisions between stakeholders and the project team as well. And although the results can be breathtaking when you look at it later, it is certainly disruptive while the building-up part is going on. Car wrecks are sudden, spectacular and breathtaking too - just not very healthy for the stakeholders.

The main feature about this methodology is the use of sudden change to complete the project after a long quiet buildup. With little or no warning, there is a flurry of activity, a lot of energy expended, and suddenly it is over and things will never be the same again.

One of the problems with this approach from a people perspective is that sudden, unexpected change tends to cause resentment and feelings of loss to those affected. This may be the users of the old system, or a person whose house was flattened by the Richter 9.5 triggered by the nearby hill's ambition to suddenly become a mountain. In both cases, you have ripped out the foundations from underneath people with no warning or preparation - in other words, there was no Change Management Plan . Put simply, there was not a lot of communication about what was coming, period.

One minute, you and all your fishy buddies are swimming away close to the shoreline, and then - BAM!- you are high and dry and upwardly mobile. No change management plan for you - learn to walk and breathe air, or die. Not everyone survives this type of project.

In real life, an event like this results in a major earthquake - and it is usually not the last. There is almost always an adjustment period, as things settle into place - accompanied by a rash of smaller earthquakes over time. Expect the same things on your Thrust Fault projects - when you suddenly change or impose things on your users, there will be a lot of adjusting, support and probably apologizing to do before they settle in to the new way of things.

Project Change Requests in this type of project are rarely uneventful.

And like the vertical adjustment to Mt Cook a couple years back, where a huge chunk of rock slid off the peak down into the valley, not everyone will want to stay on after the thrust fault event, but they might not leave right away. Just don't be surprised when they do leave.

Of course, not all Thrust-Fault projects are bad news. If you are launching a new product or a rocket to the stars, you will necessarily have your major event at the end. There will be a lot riding on the outcome, and a lot of internal activity leading up to it - but it is not as visible as the actual public launch.

Volcanic ProjectsVolcanoes get a bad rap. Compared to the energies and destruction caused by raising a thrust-fault mountain range, volcanoes are positively gentle. When they are first forming, you have plenty of warning that they are coming - gas venting, steam, warming of the water. Once they clear the water, they even provide you with night-lights to stay clear as the red-hot magma flows down the mountain side. If it thinks you are getting to close for your own safety, it may blow off some steam or ash. They are playful too - they may toss you a few pyroclastic boulders. (I don't recommend you do the "catching" part though). Sometimes you even get a free fireworks display.

Sure, they can cause destruction and changes to the terrain, but aside from ash clouds there are limited effects far from the volcano. Lava flows downhill, boulders can only be tossed so far. I am not downplaying ash clouds though - they can be very disruptive to the areas coated with ash - nearby and far afield, and they are a threat to aircraft. However this is a matter of perspective. None of us have seen a mountain range suddenly thrust out out of the earth beneath you. Volcanic eruptions are much more common in comparison. It is unlikely you would survive a mountain-building thrust fault event near you - you have a much higher chance of survival being near a volcano, as bad as it may seem.

The main feature about this methodology that makes it preferable on most projects is that while you are building your volcano, it is a gradual process. You have plenty of time to communicate with those affected and utilize a Change Management Plan as you build up towards the project goals, layer by layer. Sure, there will be some excitement and fireworks, but most of the growth in your project will be like the layering of magma as the volcano grows taller. While magma is flowing, the Volcano is actually relatively happy - there is a steady release of pressure without excessive build-ups. It is only when you run into obstacles and blockages that you have a danger of outbursts or violent eruptions. But again - you have the element of time. It takes many years to grow a volcano, so even though there seems to be bursts of short-term activity, the overall progress is relatively steady.

The one trick with volcanoes, of course, is the Project Change Requests. With a Thrust Fault project, you know to expect a flurry of these after the main event, and then things will tail off. With the Volcanic Project, things may seem to be quiet for a long period and then you may have an unexpected eruption of post-build activity.

Not a problem, really - unless you decided to build your house on the side of the volcano because of the nice view.

SummarySo what kind of project are you on? Thrust-Fault or Volcano? The needs of your project will generally dictate which approach is best.

If your project outcome is necessarily a sudden cut-over or launch type event, you might need to use Thrust-Fault. (Just do as much as you can on the communication side of things)If your project outcome affects a lot of people, it is usually best to use the Volcano approach when you can - build up slowly, and employ your Change Management Plan liberally.

The key is to keep an eye on how your project is turning out - if you planned for a Volcano, watch that you don't end up with a Thrust-Fault because you stopped communicating. It makes for a strangely shaped deliverable.

Good luck with your projects, and if you get a chance, come on "down under" to visit New Zealand. You will see an amazing variety of geology and scenery if you do!

Gary Nelson, PMP

Gazza Consulting Services

Published on August 08, 2012 03:46

July 23, 2012

Lather, Rinse, Repeat - Why We Need to Re-Plan Projects

[Also available as a podcast]

Lather, Rinse, Repeat.

You will find these instructions (or some variation) on most shampoo bottles. Why include these instructions in the first place? Does it mean that the shampoo is actually not that good and you need a double dose? Or, could it possibly be they think you are extra dirty and need the extra round of cleaning (which might be kind of insulting)?

Actually, it is neither of those reasons.

The shampoo is not necessarily faulty, nor are you likely that gamey. The reason they put those instructions on the bottle is that they know the secret of doing a job effectively. The first round cleans most of the pollution, grease and dirt out of your hair - the next round does a final pass to make sure your hair is actually clean, and not just "less dirty".

Other two-part solutions abound - floss before you brush your teeth; your teeth will be healthier if you loosen up the stuff that is stuck between your teeth and then brush and rinse it away.

Painting a room? Don't ever believe the "one coat" label on the can or the brush. Every good painter (DIY or professional) knows that you need (at least) two coats for a good finish. One time round is simply not enough, unless you are freshening up the room with the same exact colour within a couple years. But if you change colours, you will need two coats, and possibly a primer/sealer before that to help hide the old colour. And the bigger the colour change between old and new, the more coats you are likely to need to cover it.

Not surprisingly, the same approach applies to Project Planning, however we are not limited to just a second pass; depending on the length of your project you may end up doing multiple rounds of re-planning to make sure that things are going to get done effectively.

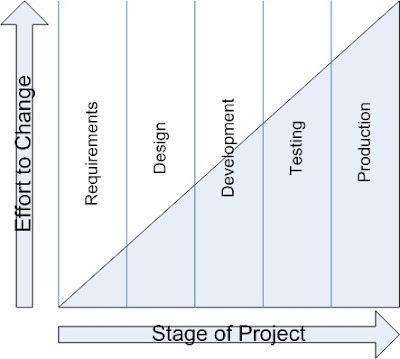

Because - as every Project Manager knows, your project plan becomes obsolete the moment you save it or print it out.

Your Project Plan Has a Best Before DateEvery project plan has a best before date. What that date is depends on a number of factors, including the number of "moving parts", work streams, dependencies and the overall complexity of your project. Even "set in stone" dates can change, for example you have had training booked in from several months ago, and then a tornado flattens the training center in the middle of the night. One way or another, you are going to have to adjust your plans - delay or relocate.

As Project Managers, we are actually tweaking the direction every day - usually small changes, adjustments, a day or two here, a resource there. Gradually, bit by bit - the reality of your project wanders off away from the path you originally set out on. You might even need to continue on the path you are on right now - but for everyone involved, it is important that you do so consciously, as part of the plan. Or perhaps you need to get back on track, regroup, assess and re-chart your path back to the destination.

When your project is starting to look substantially different from the plan, or every month or so, whichever comes first, you should be reviewing and adjusting the overall plan.

Because after all - we don't actually have an auto-pilot.

How Autopilot WorksYou may not know this, but most commercial aircraft can take off, fly and land by themselves. We are all familiar with the middle part - the flying part, but they can actually do the rest as well. They rarely use it for takeoff and landing, but they do test it from time to time when the conditions are good, with a human hand ready to take over at a moment's notice. Fortunately for us, projects are so complex and conditions so variable that no-one has yet invented an "Automatic Project Manager" to initiate and complete projects.

What is worth looking at, however, is how autopilot actually works. Every moment of your flight, you are flying slightly off-course. The wind nudges you a little up or down, left or right. If your plane kept flying in that adjusted direction, you would end up hundreds of miles or more from your destination. Fortunately, the auto-pilot knows where you came from, where you are now, and where you are supposed to end up. So every so often, at least every few minutes, the plane adjusts the rudder or ailerons to put you back on track.

Your project does not have an auto-pilot. Which is fortunate, as you would then not have a job much longer. Fortunately, they have you - the Experienced Project Manager to perform that function.

As long as you actually do the job of checking your direction and adjusting course back to the destination, that is. If you simply set your plan and then execute your project without checking that you are still going in the right direction, you will easily end up hundreds of miles from where you had planned to in the first place. Or, you might get "stuck in a spin" and fail to make forward progress, and spiral down, down, down until you crash.

So you should plan to make regular course adjustments - beyond the minor day to day tweaks. You need to periodically check all of your instruments, see where you are now, and where it looks like you are going, and update your project plan. There is even a Project Management word for what you do when you take stock, verify where you are and update the plan and direction. It is called baselining . It's important enough that they invented a word for it, so we might as well use it, right?

Another reason we need to re-look at the plan on a regular basis is that none of us can see very well beyond the nearby stuff - at least not the detail. And most of the time you can imagine, but not actually see the far-off destination, which may still be well over the horizon. So let's start with a Project Eye Exam to see if that can help.

20/20 Is Only Good For a Short DistanceIn my pre-teens I needed to get glasses. I had them for many, many years until I braved laser vision treatment. Best decision I ever made regarding my eyes - but anyway, the point here is that I needed corrective lenses (and eventually a permanent treatment when glasses could only do so much and things were still a bit fuzzy) to see as well as someone with "normal" vision.

But the thing with "normal" vision, or 20/20, is that it is still limited.

20/20 simply means that you can see at 20 feet what a "normal vision person" should be able to see at 20 feet - usually measured by being able to read tiny letters.

And really - 20 feet is not that far away. You can throw much farther than that.

At 25 to 30 feet, well, almost nobody can read the bottom line. And although those mountains are certainly pretty in the distance, you can't see the ski chalet or the sunbather on the upper balcony, or the title of the book they are reading - let alone the words on the page, which are the same size as the bottom line on the chart 20 feet away from you.

Our "detail" vision is limited to the things near to us. So you go out and buy a telescope - and suddenly you can see the chalet. Zoom in, and you can see the sunbather. Up the magnification and you can see the book title; notch it up further and you can read the page they are on (if only you hold the telescope steady enough and if they would just hold their hand still - it is getting to a good part!). However, you can no longer see the mountain. Perspective changes and limits what we see at one time. (You can't see the forest for the individual trees!)

The same rule applies to projects - although we generally do not speak in distance, but in time and deliverables.

The book that sunbather was reading looks really good - I think I'll go over and check it out.

When we draw up our project plans, we can define and be reasonably able to execute tasks on the schedule that are defined in days or even hours - but the further out you go, the details become more fuzzy. And so far, there is no Lasik or project telescope that has been invented that can help with resolving all of those far-off project details.

However, some things we can define (barring major risk events) with great precision into the far future - these are the anchor dates, deadlines, due dates and when you have specific booked activities. But for the rest, things tend to be more fluid and variable. And we need to keep these variable things on track if we ever hope to actually meet those deadlines, due dates and be able to deliver training course XYZ on June 1, two years from now.

It is the variability of those tasks in progress that require you to keep checking and correcting your course - and adding more and more detail.

This is a longer walk than I expected - the mountain looked so close! Well, I am almost there now so I better keep going...but I better grab some snacks along the way and work my way around that wet patch up ahead.

You can plan for what you can "see" - and have a rough plan for the next stages of the project journey. You can map things out in great detail to make it to the closest hill, but then you need to assess the lay of the land, navigate around the swamp you did not know was on the other side, and chart your next leg in detail to the next major point or milestone. It is in this way that we navigate through the world and through your projects, and make it to the destination on the other side.

One rule of thumb I have used in my project planning is this:

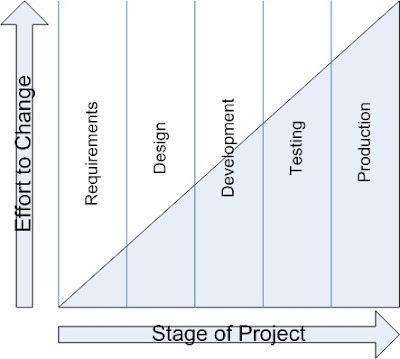

- Over the next 30 days, we can define and schedule tasks at the resolution of a day.

- Between 30-60 days, the resolution is around 2 days, give or take.

- Between 60-120 days, the resolution is at one week.

- Between 120-180 days, the resolution is at 2 weeks or more.

- Over 180 days, the resolution is at 1 month or more, and will become a summary task with more detail to be added as we get closer.

(Note that this is for duration and scheduling of assignments, not necessarily effort, though we will understand that better the closer we are to it as well).

Every time we reviewed the project plan and updated it (every month or two, if things were going relatively smoothly, or more often if not), we would review what had been accomplished so far, and then look out over the coming months and break tasks down into finer resolution and detail roughly following the model above. In this way, we had a rolling project plan with progressively more and more detail as we went along - but still a high level overview as we looked out farther into the future.

At every stage, the mountains get closer, but they are still just a little ways further off, until you finally reach your destination at the ski chalet.

The sunbather is long gone, but fortunately they left the book behind. You are also looking to rent some ski gear, because, well hey - it was a long walk and now it is early winter. But the upside is, you are here in time for ski season - and the powder is fresh, awaiting your first run. And when you finish your last run of the day, you can sit by the fire and read that book you have been looking forward to for so long.

SummaryThis article has taken us on quite a journey - from the label of a shampoo bottle to flying across the country, stopping in for an eye exam and walking long-distance to a ski resort. A mix of metaphors, perhaps, but each had a part to play in the overall lesson.

You need to be aware of your perspective when you are developing your project plan - you cannot see very many details past a fairly short period of time (weeks, or a few months). Your long-distance detail vision is not as good as you think it is. You need to Review where you are and add detail for the next group of tasks as you go.You need to make course corrections along the way. You need to Re-Plan to keep things on track, if you start to drift off course.Finally, you need to do it more than once. Perhaps not as often as an airplane, which is every few minutes - but you do need to Repeat it regularly.

So the lesson can be summarized as: "Plan your projects, and on a regular basis, Review, Re-Plan, Repeat".

Cheers and good luck with your projects. Until they develop a Project Auto-Pilot (and I hope they never do), we will just have to keep everything on track ourselves.

Gary Nelson, PMP

Gazza Consulting Services

Lather, Rinse, Repeat.

You will find these instructions (or some variation) on most shampoo bottles. Why include these instructions in the first place? Does it mean that the shampoo is actually not that good and you need a double dose? Or, could it possibly be they think you are extra dirty and need the extra round of cleaning (which might be kind of insulting)?

Actually, it is neither of those reasons.

The shampoo is not necessarily faulty, nor are you likely that gamey. The reason they put those instructions on the bottle is that they know the secret of doing a job effectively. The first round cleans most of the pollution, grease and dirt out of your hair - the next round does a final pass to make sure your hair is actually clean, and not just "less dirty".

Other two-part solutions abound - floss before you brush your teeth; your teeth will be healthier if you loosen up the stuff that is stuck between your teeth and then brush and rinse it away.

Painting a room? Don't ever believe the "one coat" label on the can or the brush. Every good painter (DIY or professional) knows that you need (at least) two coats for a good finish. One time round is simply not enough, unless you are freshening up the room with the same exact colour within a couple years. But if you change colours, you will need two coats, and possibly a primer/sealer before that to help hide the old colour. And the bigger the colour change between old and new, the more coats you are likely to need to cover it.

Not surprisingly, the same approach applies to Project Planning, however we are not limited to just a second pass; depending on the length of your project you may end up doing multiple rounds of re-planning to make sure that things are going to get done effectively.

Because - as every Project Manager knows, your project plan becomes obsolete the moment you save it or print it out.

Your Project Plan Has a Best Before DateEvery project plan has a best before date. What that date is depends on a number of factors, including the number of "moving parts", work streams, dependencies and the overall complexity of your project. Even "set in stone" dates can change, for example you have had training booked in from several months ago, and then a tornado flattens the training center in the middle of the night. One way or another, you are going to have to adjust your plans - delay or relocate.

As Project Managers, we are actually tweaking the direction every day - usually small changes, adjustments, a day or two here, a resource there. Gradually, bit by bit - the reality of your project wanders off away from the path you originally set out on. You might even need to continue on the path you are on right now - but for everyone involved, it is important that you do so consciously, as part of the plan. Or perhaps you need to get back on track, regroup, assess and re-chart your path back to the destination.

When your project is starting to look substantially different from the plan, or every month or so, whichever comes first, you should be reviewing and adjusting the overall plan.

Because after all - we don't actually have an auto-pilot.

How Autopilot WorksYou may not know this, but most commercial aircraft can take off, fly and land by themselves. We are all familiar with the middle part - the flying part, but they can actually do the rest as well. They rarely use it for takeoff and landing, but they do test it from time to time when the conditions are good, with a human hand ready to take over at a moment's notice. Fortunately for us, projects are so complex and conditions so variable that no-one has yet invented an "Automatic Project Manager" to initiate and complete projects.

What is worth looking at, however, is how autopilot actually works. Every moment of your flight, you are flying slightly off-course. The wind nudges you a little up or down, left or right. If your plane kept flying in that adjusted direction, you would end up hundreds of miles or more from your destination. Fortunately, the auto-pilot knows where you came from, where you are now, and where you are supposed to end up. So every so often, at least every few minutes, the plane adjusts the rudder or ailerons to put you back on track.

Your project does not have an auto-pilot. Which is fortunate, as you would then not have a job much longer. Fortunately, they have you - the Experienced Project Manager to perform that function.

As long as you actually do the job of checking your direction and adjusting course back to the destination, that is. If you simply set your plan and then execute your project without checking that you are still going in the right direction, you will easily end up hundreds of miles from where you had planned to in the first place. Or, you might get "stuck in a spin" and fail to make forward progress, and spiral down, down, down until you crash.

So you should plan to make regular course adjustments - beyond the minor day to day tweaks. You need to periodically check all of your instruments, see where you are now, and where it looks like you are going, and update your project plan. There is even a Project Management word for what you do when you take stock, verify where you are and update the plan and direction. It is called baselining . It's important enough that they invented a word for it, so we might as well use it, right?

Another reason we need to re-look at the plan on a regular basis is that none of us can see very well beyond the nearby stuff - at least not the detail. And most of the time you can imagine, but not actually see the far-off destination, which may still be well over the horizon. So let's start with a Project Eye Exam to see if that can help.

20/20 Is Only Good For a Short DistanceIn my pre-teens I needed to get glasses. I had them for many, many years until I braved laser vision treatment. Best decision I ever made regarding my eyes - but anyway, the point here is that I needed corrective lenses (and eventually a permanent treatment when glasses could only do so much and things were still a bit fuzzy) to see as well as someone with "normal" vision.

But the thing with "normal" vision, or 20/20, is that it is still limited.

20/20 simply means that you can see at 20 feet what a "normal vision person" should be able to see at 20 feet - usually measured by being able to read tiny letters.

And really - 20 feet is not that far away. You can throw much farther than that.

At 25 to 30 feet, well, almost nobody can read the bottom line. And although those mountains are certainly pretty in the distance, you can't see the ski chalet or the sunbather on the upper balcony, or the title of the book they are reading - let alone the words on the page, which are the same size as the bottom line on the chart 20 feet away from you.

Our "detail" vision is limited to the things near to us. So you go out and buy a telescope - and suddenly you can see the chalet. Zoom in, and you can see the sunbather. Up the magnification and you can see the book title; notch it up further and you can read the page they are on (if only you hold the telescope steady enough and if they would just hold their hand still - it is getting to a good part!). However, you can no longer see the mountain. Perspective changes and limits what we see at one time. (You can't see the forest for the individual trees!)

The same rule applies to projects - although we generally do not speak in distance, but in time and deliverables.

The book that sunbather was reading looks really good - I think I'll go over and check it out.

When we draw up our project plans, we can define and be reasonably able to execute tasks on the schedule that are defined in days or even hours - but the further out you go, the details become more fuzzy. And so far, there is no Lasik or project telescope that has been invented that can help with resolving all of those far-off project details.

However, some things we can define (barring major risk events) with great precision into the far future - these are the anchor dates, deadlines, due dates and when you have specific booked activities. But for the rest, things tend to be more fluid and variable. And we need to keep these variable things on track if we ever hope to actually meet those deadlines, due dates and be able to deliver training course XYZ on June 1, two years from now.

It is the variability of those tasks in progress that require you to keep checking and correcting your course - and adding more and more detail.

This is a longer walk than I expected - the mountain looked so close! Well, I am almost there now so I better keep going...but I better grab some snacks along the way and work my way around that wet patch up ahead.

You can plan for what you can "see" - and have a rough plan for the next stages of the project journey. You can map things out in great detail to make it to the closest hill, but then you need to assess the lay of the land, navigate around the swamp you did not know was on the other side, and chart your next leg in detail to the next major point or milestone. It is in this way that we navigate through the world and through your projects, and make it to the destination on the other side.

One rule of thumb I have used in my project planning is this:

- Over the next 30 days, we can define and schedule tasks at the resolution of a day.

- Between 30-60 days, the resolution is around 2 days, give or take.

- Between 60-120 days, the resolution is at one week.

- Between 120-180 days, the resolution is at 2 weeks or more.

- Over 180 days, the resolution is at 1 month or more, and will become a summary task with more detail to be added as we get closer.

(Note that this is for duration and scheduling of assignments, not necessarily effort, though we will understand that better the closer we are to it as well).

Every time we reviewed the project plan and updated it (every month or two, if things were going relatively smoothly, or more often if not), we would review what had been accomplished so far, and then look out over the coming months and break tasks down into finer resolution and detail roughly following the model above. In this way, we had a rolling project plan with progressively more and more detail as we went along - but still a high level overview as we looked out farther into the future.

At every stage, the mountains get closer, but they are still just a little ways further off, until you finally reach your destination at the ski chalet.

The sunbather is long gone, but fortunately they left the book behind. You are also looking to rent some ski gear, because, well hey - it was a long walk and now it is early winter. But the upside is, you are here in time for ski season - and the powder is fresh, awaiting your first run. And when you finish your last run of the day, you can sit by the fire and read that book you have been looking forward to for so long.

SummaryThis article has taken us on quite a journey - from the label of a shampoo bottle to flying across the country, stopping in for an eye exam and walking long-distance to a ski resort. A mix of metaphors, perhaps, but each had a part to play in the overall lesson.

You need to be aware of your perspective when you are developing your project plan - you cannot see very many details past a fairly short period of time (weeks, or a few months). Your long-distance detail vision is not as good as you think it is. You need to Review where you are and add detail for the next group of tasks as you go.You need to make course corrections along the way. You need to Re-Plan to keep things on track, if you start to drift off course.Finally, you need to do it more than once. Perhaps not as often as an airplane, which is every few minutes - but you do need to Repeat it regularly.

So the lesson can be summarized as: "Plan your projects, and on a regular basis, Review, Re-Plan, Repeat".

Cheers and good luck with your projects. Until they develop a Project Auto-Pilot (and I hope they never do), we will just have to keep everything on track ourselves.

Gary Nelson, PMP

Gazza Consulting Services

Published on July 23, 2012 14:04

July 15, 2012

Decisions, Decisions...A Theory on the Origin of Writing

[Also available as a podcast]

Decisions, decisions.

We each make thousands of decisions every day. Some studies have indicated that the number is at least 5,000, and possibly up to 35,000 decisions every day. Most of these are small decisions, done subconsciously, or on auto-pilot.

The conscious decisions we make every day are far fewer - but still easily in the high hundreds. The important decisions are fewer again, depending on the day. Some decisions may not even seem important until later on. But decisions we make, in the thousands, every single day of our lives. Even when you say that you can't make a decision - that is a decision to leave things as they are.

Theory on the Origin of Written LanguageI have a theory about the origin of written language. There are many in-depth philosophical, scientific and scholarly theories and analyses on the origin and stages of writing in its various forms, from proto-writing through the various scripts, hieroglyphs and alphabets.

My theory is not about the how or when of when the various forms of written language were developed as proposed by those theorists. My theory is about why written language was developed in the first place - at any place in the world you like, regardless of the time period, style, method or medium.

So here is my theory, developed over the course of an afternoon, including a short nap:

Written language was developed because of all of the decisions we make.

More specifically, the important decisions.

The Purpose of Written LanguageThe oral tradition of history is a great way to entertain and educate around campfires at night, but it is not a very reliable way of passing a consistent message across generations. Each speaker forgets a little bit, adds a little bit, or embellishes the stories a little bit. With every generation, giants get larger (8 foot! no, 9 foot! no, 11 feet tall!), enemies get more devious, more vicious, and more numerous. Heroes get more and more heroic, until they become larger than life. Details change.

The other problem is that people forget things. How many times have you been told something and then have to ask what it was they said? It may not be because you were not paying attention, it may be there was a long list of things to remember and your memory is not that good (or not as good as it was). You also have more difficulty in remembering specific details about conversations held months before, and this is normal.

Do you go to the grocery store with only a list in your head, and expect to remember to buy everything (and only those things) on your list? Rarely can any of us do that.

Decisions get made, and then they get forgotten, or miscommunicated.

I suspect that at least this much about human nature has not changed much over thousands of years.

I believe that in every culture that developed a written language, this frustration finally came to a head.

"Enough!" one leader finally would say. "I am tired of repeating myself and having things be misinterpreted. If you can't remember exactly what I am telling you, we need a better way to communicate this. I want my decisions to be clearly understood and carried out by all of my people."

It probably went something like that. Obviously not word for word, of course, as it was not written down yet (!) However, invention often comes as a result of needing to alleviate great pain, and anyone trying to rule a kingdom by the spoken word alone must have had a lot of headaches. You also had to really, really trust the people you sent out with your commands to get it right and not change it, and remember it as best they could.

So a great project would begin - to design some form of written symbols to represent the spoken language. Everyone who formed part of the communication network would have needed to be trained in the reading of the symbols, and the trusted few would be trained on inscribing the symbols.

The other benefit of a written language is that the King could expand his empire and maintain consistency of his rule - just look at the expansion of the Roman Empire as an example of what could be accomplished.

Most of the population would not have been trained in reading or writing of the symbols - it would have required a lot of effort to do so, and being able to read and write was an elite skill that formed part of the power structure. Carry the written word (symbols, hieroglyphs, script) from the central point of decision making, and then read out those words in the outlying regions - exactly as they had been inscribed at the source.

Written language symbols would have most likely been used primarily to record edicts and legal matters - important things, specifically, important decisions. Various mediums would have been tested and used - bark, cloth, animal skins, silk, reed fibre mats and others. Some were obviously more portable than others, and some more durable; some messages were of such significance that they were literally "written in stone" on rock or clay tablets, intended to last for a long time.

Babylonian legal tablet in stone envelope (Source: Wikipedia)

Babylonian legal tablet in stone envelope (Source: Wikipedia)

If you look at the various forms of written communication that have been unearthed, many of the less durable materials have decayed, but the more durable (clay tablets and stone) remain readable today. And what do we tend to find on those tablets? Decisions! Royal edicts, legal matters, business records. All outcomes of important decisions.

Very few people recorded shopping lists on stone tablets, but you can be sure there were a lot of those too, on less permanent materials. And what are shopping lists but recorded decisions of what you need to buy?

Note that literature and "pulp fiction" came much, much later - once the printed word became more accessible to the masses through the invention of the printing press.

Going forward to the present day, you will see that legacy remains - most of the written word revolves around decisions, even in fictional stories. You read about the lead-up to decisions, how people wrestle with difficult decisions, the decision as it is made, the outcome of the decisions, the justification for why they made bad decisions, and on it goes. A single book contains thousands upon thousands of decisions, and even dry textbooks describing new concepts to you are the result of others deciding what was important to tell you about the topic.

Contracts are just another form of written decisions - what has been agreed to with respect to who is going to do what, who will pay whom, and what any penalties will be for non-conformance, and so on. Requirements documents? Recorded decisions about what they want you to do.

There may be some exceptions, in some poetry perhaps, but the primary focus of the written word is still wrapped in the legacy of decision-making and recording the framework of decisions.

But is this any surprise, considering each one of us makes so many decisions, every single day?

So there is my theory. It might not even be original, as many ideas are variants of other people's ideas, but I think you will agree there is some merit to it anyway.

Your Project and Decisions How does this apply to your project? Well, in every project, there are many decisions made every single day. Some are minor, some are major and some are of great significance, either to scope, budget, time frame, or what needs to be done in order to accomplish the project goals.

Depending on the size of your project, you may have a formal Decision Log that records the disposition of major decisions that are made by the appropriate stakeholders; in your Responsibility Assignment Matrix you will have identified all of the stakeholders and project team members. A subset of these people, usually the Project Sponsor and a select group of stakeholders will be the key decision makers for your project, and you may possibly have a Change Control Board as well.

Make sure that you accurately track all of those major decisions and their outcomes, not only for the project audit, but to help ensure that everyone gets the same message about what those decisions were during your project.

For less major decisions, you may not need the Project Sponsor or the stakeholders involved; you may have these only at the level of your project team.

The decisions may relate to the scope of the project, costs, time frame, or any number of technical details regarding the execution of your project.

However, the key and important message here is to write things down . Most decisions may be arrived at through verbal discussion, but the decision and it disposition (and contributing factors) need to be recorded. This may be on paper, electronic documents or in emails, but get the information into a written form.

Don't forget to communicate the outcomes of those decisions - again, in written form. You may talk about them as well, when explaining them in front of a group, but there is more weight when things are written down.

Again, we all make thousands of decisions per day, but some need to be recorded, especially as they relate to the project. A good rule of thumb to use is if it materially affects the direction or outcomes of the project (cost, scope, timeline) or is anything that someone may come back to ask you about later on, write it down . Or type it in a log somewhere you can easily find it.

This is important because people forget, and their memories of events change and differ over time. If you write it down, both parties can review what was recorded; end of dispute over who remembered what best and who was "right"; often neither of you remember correctly.

If in doubt, write it out!

SummaryEver since High School I have written things down. You will usually find me with a notebook nearby; however these days I am able to record notes and emails on my phone, so no extra baggage required if I am out and about. But I still use a paper notebook while I work. The interesting thing I have found is that the more I write things down, the better I remember them. And if I do get fuzzy on the details later on, I know that I wrote something down about it a few months (or years) back, and am able to find the reference in a notebook. Sometimes all I write in my notebook is something to jog my memory, or a reference of where the full details are recorded elsewhere - in a document or an email. But even with that small note, I find that I am able to recall the event in detail.

Many years ago now, a customer encountered an issue that seemed familiar to me. I knew I had seen it before but could not remember the specifics or the solution - but I knew I had written it down, and approximately which month of what year (three years before). Within 10 minutes I was able to find the reference and recount the full scenario and the solution. It impressed my colleagues and the customer, but it was really a matter of making a habit of writing things down, especially the important things.

The only times I have been stuck, unable to recount the full details or an event or decision was when I neglected to record a note in my book. I may have been tired that afternoon and not felt like writing things down...and often, that would come back to bite me. So I still record notes in my notebook - and I have a closet full of them, numbered and going back many years. Of course, I use email and documents for most of my written communication these days, but the principle is the same - I can search through emails, and I will usually remember the year and month when I sent or received it as well.

Many ancient societies spent the intense effort to develop various forms of the written word, which have evolved into the various written languages we have today. And they did it all for you - and future generations, so that you can read about past decisions, and record yours for future generations, or at least for communicating within your project team (and for the project audit).

Honor the efforts of those many generations and millions of people who labored to develop the written forms of language (just for you!) - and write the important stuff down .

Good luck with your projects, and keep good notes. You'll need them for later on.

Gary Nelson, PMP

Gazza Consulting Services

Decisions, decisions.

We each make thousands of decisions every day. Some studies have indicated that the number is at least 5,000, and possibly up to 35,000 decisions every day. Most of these are small decisions, done subconsciously, or on auto-pilot.

The conscious decisions we make every day are far fewer - but still easily in the high hundreds. The important decisions are fewer again, depending on the day. Some decisions may not even seem important until later on. But decisions we make, in the thousands, every single day of our lives. Even when you say that you can't make a decision - that is a decision to leave things as they are.

Theory on the Origin of Written LanguageI have a theory about the origin of written language. There are many in-depth philosophical, scientific and scholarly theories and analyses on the origin and stages of writing in its various forms, from proto-writing through the various scripts, hieroglyphs and alphabets.

My theory is not about the how or when of when the various forms of written language were developed as proposed by those theorists. My theory is about why written language was developed in the first place - at any place in the world you like, regardless of the time period, style, method or medium.

So here is my theory, developed over the course of an afternoon, including a short nap:

Written language was developed because of all of the decisions we make.

More specifically, the important decisions.

The Purpose of Written LanguageThe oral tradition of history is a great way to entertain and educate around campfires at night, but it is not a very reliable way of passing a consistent message across generations. Each speaker forgets a little bit, adds a little bit, or embellishes the stories a little bit. With every generation, giants get larger (8 foot! no, 9 foot! no, 11 feet tall!), enemies get more devious, more vicious, and more numerous. Heroes get more and more heroic, until they become larger than life. Details change.

The other problem is that people forget things. How many times have you been told something and then have to ask what it was they said? It may not be because you were not paying attention, it may be there was a long list of things to remember and your memory is not that good (or not as good as it was). You also have more difficulty in remembering specific details about conversations held months before, and this is normal.

Do you go to the grocery store with only a list in your head, and expect to remember to buy everything (and only those things) on your list? Rarely can any of us do that.

Decisions get made, and then they get forgotten, or miscommunicated.

I suspect that at least this much about human nature has not changed much over thousands of years.

I believe that in every culture that developed a written language, this frustration finally came to a head.

"Enough!" one leader finally would say. "I am tired of repeating myself and having things be misinterpreted. If you can't remember exactly what I am telling you, we need a better way to communicate this. I want my decisions to be clearly understood and carried out by all of my people."

It probably went something like that. Obviously not word for word, of course, as it was not written down yet (!) However, invention often comes as a result of needing to alleviate great pain, and anyone trying to rule a kingdom by the spoken word alone must have had a lot of headaches. You also had to really, really trust the people you sent out with your commands to get it right and not change it, and remember it as best they could.

So a great project would begin - to design some form of written symbols to represent the spoken language. Everyone who formed part of the communication network would have needed to be trained in the reading of the symbols, and the trusted few would be trained on inscribing the symbols.

The other benefit of a written language is that the King could expand his empire and maintain consistency of his rule - just look at the expansion of the Roman Empire as an example of what could be accomplished.

Most of the population would not have been trained in reading or writing of the symbols - it would have required a lot of effort to do so, and being able to read and write was an elite skill that formed part of the power structure. Carry the written word (symbols, hieroglyphs, script) from the central point of decision making, and then read out those words in the outlying regions - exactly as they had been inscribed at the source.

Written language symbols would have most likely been used primarily to record edicts and legal matters - important things, specifically, important decisions. Various mediums would have been tested and used - bark, cloth, animal skins, silk, reed fibre mats and others. Some were obviously more portable than others, and some more durable; some messages were of such significance that they were literally "written in stone" on rock or clay tablets, intended to last for a long time.

Babylonian legal tablet in stone envelope (Source: Wikipedia)

Babylonian legal tablet in stone envelope (Source: Wikipedia)If you look at the various forms of written communication that have been unearthed, many of the less durable materials have decayed, but the more durable (clay tablets and stone) remain readable today. And what do we tend to find on those tablets? Decisions! Royal edicts, legal matters, business records. All outcomes of important decisions.

Very few people recorded shopping lists on stone tablets, but you can be sure there were a lot of those too, on less permanent materials. And what are shopping lists but recorded decisions of what you need to buy?

Note that literature and "pulp fiction" came much, much later - once the printed word became more accessible to the masses through the invention of the printing press.

Going forward to the present day, you will see that legacy remains - most of the written word revolves around decisions, even in fictional stories. You read about the lead-up to decisions, how people wrestle with difficult decisions, the decision as it is made, the outcome of the decisions, the justification for why they made bad decisions, and on it goes. A single book contains thousands upon thousands of decisions, and even dry textbooks describing new concepts to you are the result of others deciding what was important to tell you about the topic.

Contracts are just another form of written decisions - what has been agreed to with respect to who is going to do what, who will pay whom, and what any penalties will be for non-conformance, and so on. Requirements documents? Recorded decisions about what they want you to do.

There may be some exceptions, in some poetry perhaps, but the primary focus of the written word is still wrapped in the legacy of decision-making and recording the framework of decisions.

But is this any surprise, considering each one of us makes so many decisions, every single day?

So there is my theory. It might not even be original, as many ideas are variants of other people's ideas, but I think you will agree there is some merit to it anyway.

Your Project and Decisions How does this apply to your project? Well, in every project, there are many decisions made every single day. Some are minor, some are major and some are of great significance, either to scope, budget, time frame, or what needs to be done in order to accomplish the project goals.

Depending on the size of your project, you may have a formal Decision Log that records the disposition of major decisions that are made by the appropriate stakeholders; in your Responsibility Assignment Matrix you will have identified all of the stakeholders and project team members. A subset of these people, usually the Project Sponsor and a select group of stakeholders will be the key decision makers for your project, and you may possibly have a Change Control Board as well.

Make sure that you accurately track all of those major decisions and their outcomes, not only for the project audit, but to help ensure that everyone gets the same message about what those decisions were during your project.

For less major decisions, you may not need the Project Sponsor or the stakeholders involved; you may have these only at the level of your project team.

The decisions may relate to the scope of the project, costs, time frame, or any number of technical details regarding the execution of your project.

However, the key and important message here is to write things down . Most decisions may be arrived at through verbal discussion, but the decision and it disposition (and contributing factors) need to be recorded. This may be on paper, electronic documents or in emails, but get the information into a written form.

Don't forget to communicate the outcomes of those decisions - again, in written form. You may talk about them as well, when explaining them in front of a group, but there is more weight when things are written down.

Again, we all make thousands of decisions per day, but some need to be recorded, especially as they relate to the project. A good rule of thumb to use is if it materially affects the direction or outcomes of the project (cost, scope, timeline) or is anything that someone may come back to ask you about later on, write it down . Or type it in a log somewhere you can easily find it.

This is important because people forget, and their memories of events change and differ over time. If you write it down, both parties can review what was recorded; end of dispute over who remembered what best and who was "right"; often neither of you remember correctly.

If in doubt, write it out!

SummaryEver since High School I have written things down. You will usually find me with a notebook nearby; however these days I am able to record notes and emails on my phone, so no extra baggage required if I am out and about. But I still use a paper notebook while I work. The interesting thing I have found is that the more I write things down, the better I remember them. And if I do get fuzzy on the details later on, I know that I wrote something down about it a few months (or years) back, and am able to find the reference in a notebook. Sometimes all I write in my notebook is something to jog my memory, or a reference of where the full details are recorded elsewhere - in a document or an email. But even with that small note, I find that I am able to recall the event in detail.

Many years ago now, a customer encountered an issue that seemed familiar to me. I knew I had seen it before but could not remember the specifics or the solution - but I knew I had written it down, and approximately which month of what year (three years before). Within 10 minutes I was able to find the reference and recount the full scenario and the solution. It impressed my colleagues and the customer, but it was really a matter of making a habit of writing things down, especially the important things.

The only times I have been stuck, unable to recount the full details or an event or decision was when I neglected to record a note in my book. I may have been tired that afternoon and not felt like writing things down...and often, that would come back to bite me. So I still record notes in my notebook - and I have a closet full of them, numbered and going back many years. Of course, I use email and documents for most of my written communication these days, but the principle is the same - I can search through emails, and I will usually remember the year and month when I sent or received it as well.

Many ancient societies spent the intense effort to develop various forms of the written word, which have evolved into the various written languages we have today. And they did it all for you - and future generations, so that you can read about past decisions, and record yours for future generations, or at least for communicating within your project team (and for the project audit).

Honor the efforts of those many generations and millions of people who labored to develop the written forms of language (just for you!) - and write the important stuff down .

Good luck with your projects, and keep good notes. You'll need them for later on.

Gary Nelson, PMP

Gazza Consulting Services

Published on July 15, 2012 01:29

July 2, 2012

Once Upon A Time: Your Project is a Story

[Also available as a podcast]

On July 1, 2012, my teenage son and I went to a book signing. My son's first time going to one - and it was for one of his all-time favourite authors. The author was in Hamilton, NZ for the last stop, and last "show" on his tour for the final book in the series. The next day, he was flying home.

Dragons, Magic, Dwarves, Elves, Wizards, dark forests - the core elements of every good fantasy novel are in his books.

The author spoke with the crowd for nearly an hour, telling of his journey of writing. It was quite an interesting story, and he was a dynamic speaker. At the end, during Q&A one of the members of the audience asked "how do you go about writing a book"?

The answer was insightful. His answer was that it was in exactly the same way as every other author he had met started to write their stories. The authors all started with Questions. "What if...?", "How about if the character did this...?", "Why can't we just...?" and so on.

That got me to thinking about Projects. Doesn't every project start the same way - with a lot of Questions?

Your Project is a Story Anyone who has worked on a project has a few good stories to tell about what happened on the project. And if you look at the big picture of the project, while it is happening and perhaps again in the Lessons Learned session at the end (the Epilogue), you actually have all of the elements of a great novel. You have:Characters (the Project Team and stakeholders)Action (the work of getting things done)Drama (oh boy can there be drama!)Comedy (usually unplanned but welcome nonetheless)Plot (the Project Plan, or WBS)Sub-Plot (what really happens at the lower team levels)Intrigue (Who made that change without asking?)Mystery (Will we finish this on time, in scope and on budget?)Quests (Goals)Heroes (hopefully this is all of us)Monsters (and a few nasty ones, too!)Villains (not necessarily people, this can be scope creep and the like)And sometimes, a surprise ending.So, in truth - a project really is a story! And probably a good read too, once it is all done.

Note that I am not just referring to Agile here, where the "unit of work" is referred to as a story. I am talking about the higher level genre here - independent of your system, methodology (or mythology). Projects (as a whole) are stories. Story drafts of what you would like to achieve - and the final version, where the true ending is not known until the project is finished.

The Story OutlineEvery author starts with an idea, an outline of their story that gets fleshed out as they begin to write. Chapter by chapter, the story grows - usually following the general directions of the outline they started with, but occasionally taking unexpected turns (even for the author) as the story begins to take on a life of its own.

It is much the same on our projects. We start with a high level idea, a concept during Project Initiation (the Prologue).We then get into the Planning phase (preparing for the adventure or journey). Then we are off into the wild, wild world in the Execution phase (and unlike many adventure stories, we do want most of the characters to reach the end at least mostly alive). In some stories there is certainly a lot of Executing going on! And during the execution of our projects, we often have to take unexpected turns, retrace our steps and change our plans.And finally, we reach the end - with the victory feast in the Great Hall, celebrating the victory and sharing stories and lessons learned from our travels. (Project Closeout).And overseeing it all is the Narrator (the Project Manager), subtly guiding the story (Project Control).

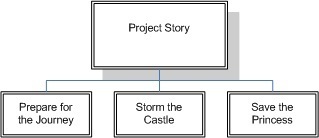

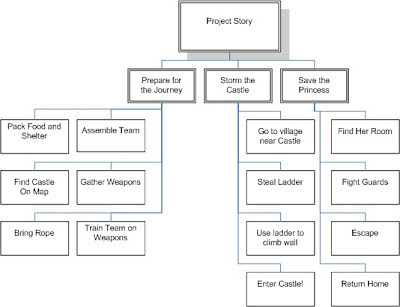

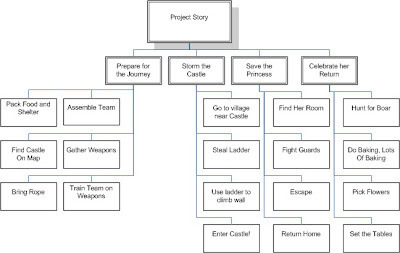

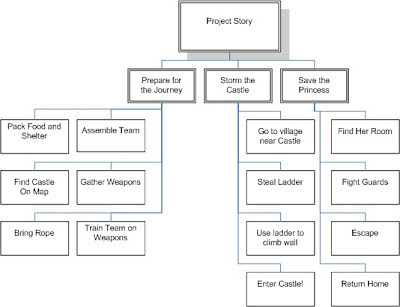

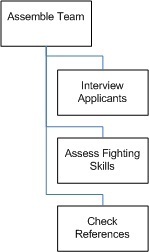

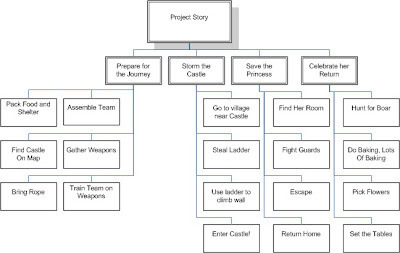

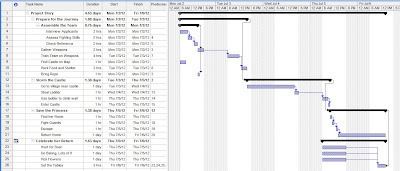

Crafting your Story OutlineSo you have a project to deliver. You have the high level goals, but you are not sure how to get started. You have the end in mind, but you are not sure how to get there. You need to begin crafting your story outline - how to get "there" from "here". In our projects, we have another name for this. We call it the Project Plan, or Work Breakdown Structure (WBS).

"Yes, I understand that", you say - "of course we need a Project Plan and WBS. But how do we get started?"

If you have worked on similar projects before, you will probably have a very good idea of what needs to happen when, and in what sequence. You will likely copy one of those plans, review the outline, and start tweaking it to write up your draft outline of the WBS for your new project. In this case, you are working along the lines of a "Gilt" novel. (That is not a misspelling.) Gilt, not Guilt. As in the shiny gold lettered covers of most Romance novels. We are not saying your project is going to be a romance, or that it should be treated lightly. What it means is this type of novel follows a prescribed structure, format, or formula - the basic plotline is the same "type", but the characters, location and the model of flashy sports-car the Hero (or Heroine) drives changes. If you have this type of project, you are probably off to a good start and you know most of the storyline already.

Uncharted Lands

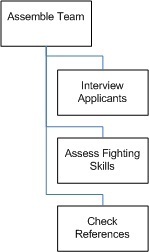

But what about when you are working on something entirely new, or at least new to you? You need to start from scratch, taking the high level goals and breaking them down into smaller and smaller achievable pieces. You don't go straight from being a farmhand in the village to storming the castle keep in one chapter - you have to meet your band of heroes, train up, gain weapons, learn skills, buy or steal some ladders (and maybe a battering ram) before you approach the castle.

In short - we need to literally break things down into a story. You may not have castles, dragons, dungeons or swords - you may have concrete and girders, server rooms and code instead. But the principle is exactly the same.

Once Upon a Time...Every project starts with a problem to solve.

"The Princess has been kidnapped and taken to the castle!"

We need to start, as any good story does, with words. And not just any words, either. We need a few special types of words and phrases in order to define our story outline, or WBS. Same thing. We need:

Goal words and phrases. Things to be achieved. The things we need to complete, to deliver. In our story, these would be the goals of our quests. "We need to rescue the Princess!"Action words and phrases. Actions we need to take, in order to accomplish the goals and complete the Quest. "Storm the Castle" and "Save the Princess" are a good start. Note that these can also be goal words with sub-goals, but they are all about getting things done!And depending on your style (and dot the i's and cross the t's)

Completed action statements (milestones, goal achieved - so we know when we have succeeded). "Princess rescued!"

What you will find, as happens in any story, is that there is a grand vision, an overall set of lofty goals to achieve in order to solve our problems - usually at a very high level. So our initial vision statement is deceptively simple.

"Let's storm the castle and rescue the Princess!"

So, grab your pitchforks and head off into the night! ... Until the wise old man from the village (usually weatherworn, wearing a hooded cape, and a bit mysterious) calls you back and tells you that you are not ready to go quite yet. You need to Prepare, and then you can Storm the Castle and Save the Princess.

We need to prepare, and put a bit more detail into our plan. We need to think about what needs to go into the Deliverable Goals (Storm the castle) and (Save the Princess). What do we need to bring? Who do we need to go with us? What are we going to do when we get there? Once we get in, how do we get the Princess?

And on, and on. Notice the key thing here - there are lots and lots of questions. From asking the questions and figuring out the basic answers, we develop our progressively more detailed plan, with smaller and smaller goals under each higher level goal.