M.J. Westerbone's Blog, page 3

October 21, 2020

My favourite writers of medieval fiction – No2 – Paul Doherty – the Hugh Corbett Series

I first came across Paul Doherty’s books via his Hugh Corbett series, set during the 13th-century reign of Edward I of England. There are now twenty-one books in the series as of 2020’s “Hymn to Murder”. I have loved this series since the first book was published back in the late 1980s. Doherty has written something like 100+ published works under a variety of pen names alongside his real name. The sheer volume and quality of his literary output is quite amazing. The other series of his I’m familiar with is the “Sorrowful Mysteries of Brother Athelstan”, set during the 14th-century reign of Richard II of England. Again a great read. The series will be on book twenty as of December 2020. I highly recommend both series, Doherty is an absolute master of the historical mystery genre.

I first came across Paul Doherty’s books via his Hugh Corbett series, set during the 13th-century reign of Edward I of England. There are now twenty-one books in the series as of 2020’s “Hymn to Murder”. I have loved this series since the first book was published back in the late 1980s. Doherty has written something like 100+ published works under a variety of pen names alongside his real name. The sheer volume and quality of his literary output is quite amazing. The other series of his I’m familiar with is the “Sorrowful Mysteries of Brother Athelstan”, set during the 14th-century reign of Richard II of England. Again a great read. The series will be on book twenty as of December 2020. I highly recommend both series, Doherty is an absolute master of the historical mystery genre.

The post My favourite writers of medieval fiction – No2 – Paul Doherty – the Hugh Corbett Series appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

October 16, 2020

Medieval Swearing, “God’s Bones!”

There are trends and fashions in swearing. Things that were outrageous and blasphemous in one age might raise nothing but a curious stare in the 21st century.

It’s difficult today to understand why swearing by parts of God’s body would be offensive, but it was a popular way of swearing up to the end of the 15th century. People would swear by “God’s Nails” or “God’s Bones”, “God’s Teeth”, even “God’s Balls!”

It a tough concept to get your head around, but I’ll try to explain it as best I understand it myself. So, to the medieval mind swearing an oath was a deadly serious affair. If you swore a sincere oath you were asking (even forcing) God in heaven to look down and guarantee what you said was in fact true. In an age where religion was an integral part of daily life, if you swore a false oath you were in effect making God out to be a liar! In addition, to swear by parts of God’s body you were literally thought to be affecting those parts of his body up in heaven. These words and phrases have a power that is mostly lost on us today, but you would use them when you trapped your finger in a door, insulted someone, even expressed joy and amazement.

On the other hand, some words and phrases which were part of everyday speech in the medieval ages would today, in polite company at least, raise eyebrows. Describing bodily functions wasn’t a big deal, and it was normal practice for something like a street name to reflect the street’s function or the economic activity taking place within it. Which explains streets in many medieval towns called Gropecuntlane, Oxford and London to name just two. You can image what went on there. The local stream might well be called the Shitebrook for similar reasons….

I confess I find this sort of stuff fascinating. It might not be your cup of tea, but if you are interested, there’s a brilliant book about the history of swearing, “Holy Sh*t” by Melissa Mohr. It’s available on amazon.

The post Medieval Swearing, “God’s Bones!” appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

October 13, 2020

My favourite writers of medieval fiction – No1 – Ellis Peters – The Cadfael Chronicles

I’ve always been a fan of historical fiction, although over the years I’ve also read a lot of science fiction. Still, I always seem to return to books set in the past, particularly the medieval period. It seems a lifetime ago (and I suppose it really is now) when I first came across The Cadfael Chronicles (a series of historical murder mysteries written by Edith Pargeter under the pen name “Ellis Peters”). The first book, A Morbid Taste for Bones, was published in the late 70s and I would guess I began reading the series in my early teens (I was a strange kid!). They feature the Benedictine monk Cadfael (of Shrewsbury Abbey) who aids the local forces of law and order in solving murders. The books were made into a very popular TV series here in the UK shown during the mid-90’s, it was also shown in the US.

Partgeter died in 1995, but I think we can credit her with being one of the authors who first really popularised what became the historical mystery genre. The books are beautifully written and might be a bit tame for some readers (I’ve seen them recently tucked under the Cosy Mystery sub-genre) but I for one always enjoyed the gentle unfolding of each story. There are twenty-one books in the series, so something to get your teeth into and highly recommended.

The post My favourite writers of medieval fiction – No1 – Ellis Peters – The Cadfael Chronicles appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

March 15, 2020

The English Medieval Penny

The most widespread coin in use in medieval England was the penny. Twelve silver pennies made a shilling and there were twenty shillings to the pound. For transactions worth less than a penny it could be divided by physically clipping the coin into halves and quarters. Hence, half pennies and quarter pennies (known as farthings). Although official half pennies and farthings existed, they don’t ever seem to have been issued in the quantities needed to stop them being anything but rarities. The clipped coins therefore being the norm for anything less than a whole penny.

In accounting the Silver mark was used, although no actual mark coins existed. One mark was equal to 13 shillings and 4 pennies, which was two-thirds of one pound.

Wages and buying power in medieval England are notoriously difficult to estimate from a modern vantage point. There are so many unknowable factors at play that everything you can find on the subject can only ever be an estimate of what things cost on a daily basis.

I’ve assumed some typical daily earnings for the lower ranks of society for the time period my books are set in (1390’s – 1420’s) which I think are fairly accurate. A labourer, manservant, maidservant or swineherd might earn between one and three pennies a day. More skilled craftsmen like masons, carpenters, thatchers and weavers might earn between three and six pennies a day. A chantry priests might earn four pennies a day and an esquire or constable in the army perhaps thirteen pennies a day.

Cheap wine was about three pennies a gallon, the good stuff perhaps eight pennies a gallon. Ale, the staple drink of everyone, was three quarters of a penny for a weak gallon of ale and one and half pennies for a gallon of a better brew. Two dozen eggs could be had for a penny and you could buy two chickens for three pennies.

The post The English Medieval Penny appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

March 3, 2020

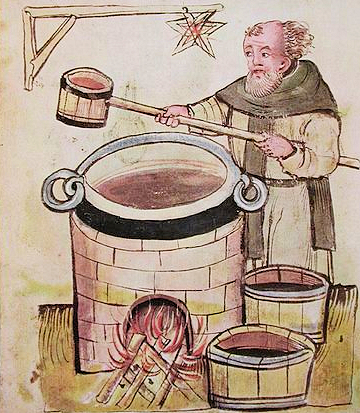

Medieval English Ale

In medieval England virtually everyone would have drunk ale on a daily basis. That’s not to imply that the whole population was constantly inebriated. The fact is medieval ale was a very different drink to any modern-day beer or ale. The basic ingredients were water and malted grain fermented with yeast (beer as oppose to ale also included hops as an ingredient). Ale was both used for hydration and nutrition and was very much an essential part of the English diet. This was a time when most people rarely drank water or milk. Although the wealthier could also afford to drink wine, ale was the overwhelming liquid refreshment of choice for much of the population. Then as now people could drink to get merry, to get drunk even, but it was also a much more mundane, day to day experience. Both children and adults drank ale, it was consumed throughout the day.

The basic ale making process consisted of the malted grain being crushed, boiling or very hot water would be added, and the mixture allowed to work. The liquid would then be drained off, cooled and fermented.

Although a relatively simple process it was also time consuming. In medieval England this type of ale would be served fresh which means it had very recently stopped fermenting or it was still in the process of fermenting. Ale did not keep well, being fast to sour and lasting at most only a few days.

The amount of ale that was brewed and consumed appears enormous to modern day eyes. For a household of five perhaps up to one and quarter gallons would be required per day.

During the fourteenth century most of the ale brewing in England was carried out by women in a domestic setting. Most households had the capability to brew ale for their own use and sometimes to sell to others. For many households it could be a valuable source of extra income even if they only sold to others a few times a year. When a fresh brew was available for others to buy a sign would be hung outside, often a broom.

The post Medieval English Ale appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.