M.J. Westerbone's Blog, page 2

February 17, 2021

And then there were three

Preparations for the release of the third book in my Draychester Chronicles series have taken longer than first planned even though we are still in strict lockdown here in England. I’m pleased to say Death of the Anchorite is now available. Will, Bernard and Osbert are once again on a mission to track down a killer in late 14th century England. As usual I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

The post And then there were three appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

January 26, 2021

The Dilemma of Advanced Reader Copies (ARCs)

Just reading my reviews on the various Amazon country sites tonight. I always approach it with a mixture of trepidation and excitement. I do honesty read them all, good or bad. Getting someone to leave even a rating is hard, and most people don’t ever leave a review. I understand, I don’t often leave reviews on the books I read either. It takes effort, and once I finish a book, I am generally off to the next shiny thing on my reading list. If you do leave a rating or review, I applaud you for taking the time, I really do.

Before publication of a book, I sometimes ask for people to review an advanced reader copy (ARC). Now an ARC is sort of a “nearly finished version” of the book before the final edit. There might be spelling errors, a few passages that might not make the final cut and other things that will get tweaked. It’s not the finished product but it’s close. If you ever get an ARC for review that’s what you need to bear in mind.

You might not know this, but you can review a book on Amazon that you haven’t actually purchased through the site. Reviews obviously help readers to decide on whether a particular book is for them or not. So, as an author, if you can get a few reviews immediately the book is published it can help with kicking in the algorithms behind the mighty Amazon selling machine. The idea is that you send out a few ARCs, people get to read the book a few weeks before publication, and then as soon as its on sale they can post a review on Amazon if they like. They don’t need to buy the book on Amazon.

Anyway, I just read one review that I know was generated via an ARC. I thought, “yikes lady”, I appreciate you leaving a review, but I soon realised what the review was based on. Not my actual book but partly on the free prequel novel to the series and partly on the ARC. The reviewer pulled me up on spelling and grammar. I’m sure she did see some problems as she was reviewing the pre-publication copy before the final edit! That’s an ARC for you. Also, she quoted parts of the storyline that aren’t actually in the book she was reviewing at all. They were in the prequel book which I presume she read before the actual ARC of the novel. Now don’t get me wrong, the fact she took the time to leave a review was fantastic. However, the actual review makes me wonder if I should continue giving out ARCs or not. It’s the first time I have done so via the storyorigins site and it’s been very hit and miss. Anyway, you live and learn…

P.S Don’t get me started on the differing spelling of the same words in US and British English. I unashamedly write using British English spelling. Why wouldn’t I? I live in England, it doesn’t make the spelling wrong…

The post The Dilemma of Advanced Reader Copies (ARCs) appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

January 1, 2021

Losing A Joust (every day since 1390!)

The Jousting Knights, Wells Cathedral Clock

A very happy new year to you all. As I sit here typing away I can hear the steady tick of my clock counting off the hours and minutes of the new year.

My dad was a carpenter / joiner and when he retired in the late 1980s he decided to make the cases for a series of grandfather clocks. Over the next few years, he made several clocks for various members of the family, including me.

The oak Dad used for the cases had come from my grandmother’s wardrobe! She lived to be 96 and I am sure she had inherited it, perhaps from her own parents, so it was probably Victorian.

Anyway, my vague memories of the famous wardrobe are of a hideous thing the size of a small tank. (They had to literally remove the window of my Grandmother’s bedroom to get it out. How it had got in there in the first place was a mystery). Hideous though it undoubtedly was, it had been made with some fabulous pieces of oak.

All of which brings me, in a round about way, to medieval clocks… Time in the modern world is a very different concept than it was to our medieval ancestors. That’s not to say time wasn’t important to them, particularly in the medieval town and city, the day could be closely regulated. The canonical hours would be sounded out by the church bells and things like a curfew bell that signalled the end of the working day were common.

During the 14th century, when my books are set, things slowly started to change regarding telling the time. Before mechanical clocks, the hours of daylight could be divided up with some measure of accuracy but during the night-time, particularly during the winter it would be very difficult to estimate how long you had until dawn.

It’s generally accepted that the first mechanical clocks, powered by water, originated in China probably in the 11th century. Weight-driven clocks were beginning to be developed in the first half of the 14th century.

Early clocks were nothing like their later descendants. They did not have hands or a clock face. As many were installed in church buildings they perhaps gave an indication that a bell was to be rung or later actually rang the bell itself. The clock would often be housed in a tower and encased in a metal frame. In England, during the early 14th century, there is some evidence for primitive clocks existing at the cathedrals / abbey in Lincoln, Norwich and Saint Albans although they may have had more to do with astronomical prediction than telling the time. By the 1350s mechanical clocks had been installed in the palaces of Edward III. However actual accurate time keeping by these devices was not a priority, clocks could lose or gain many minutes over a single day.

At this period there was not even an agreement of what precise length an hour should be. Most people accepted that in the winter there would be twelve short hours of daylight, and in the summer twelve long hours of daylight. It was only gradually that the length of an hour came to be more or less agreed upon and regulated for the whole 24 hour period. As mechanical clocks became more widespread, they certainly helped to make this a more acceptable way of dividing up the day.

Wells is a cathedral city in the southwest of England. It’s a place full of history spanning hundreds of years. The magnificent cathedral has a clock dating from the 14th century. (It also happens to be one of my favourite cathedrals, my fictional city of Draychester bears an uncanny resemblance to Wells…)

The original clock mechanism at Wells is dated between 1386 and 1392 and may be based on a slightly earlier clock that still exists at Salisbury Cathedral. The Well’s clock is an astronomical clock, as well as showing the time on a 24-hour dial, it reflects the motion of the sun and the moon.

The original dial (the oldest surviving clock face in the world) is located inside the cathedral with a later dial driven from the same mechanism located on the outside of the building.

I’ve stood and looked up at these dials with wonder. It’s like looking into the face of history. It makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up just thinking about all the other people over the ages who have stood in this spot and done the same.

Inside the catherdral, driven by the mechanism of the clock, is a figure called Jack Blandifers. He sits up and above the clock face and to the right. Every quarter hour he hits a bell with a hammer held in his right hand and two bells hung beneath him with his heels.

Jack BlandifersAbove the clock itself two knights and two Saracens, go around in a circle in a jousting tournament. One poor Saracen is knocked down on every turn, something he has endured on a regular basis since 1390. It’s a fight he’s never going to win…

If you ever get the chance, go and visit Wells and its famous cathedral. It’s a beautiful place with a fabulous history.

For videos of the clock, Jack Blandifers and the Jousting Knights see the links below:-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NjpuBiuMvFg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyKhYvBy-AA

The post Losing A Joust (every day since 1390!) appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

December 28, 2020

A Medieval Christmas

The church, which dominated so many aspects of medieval life, ensured that Christmas was a true religious holiday and a highlight of the calendar. It was the longest holiday of the year, twelve days, lasting from the night of Christmas Eve, the 24th of December, to the Twelfth Day, Epiphany, on the 6th of January. Mid-winter saw a lull in agricultural tasks and meant that everyone got the chance to enjoy some of the merriment and festivities.

Then as now, it was a season that involved decorating the home with garlands and wreaths. William Fitzstephen (a cleric and administrator in the service of Thomas Becket) writing in the 12th century recorded,

“Every man’s house, as also their parish churches, was decked with holly, ivy, bay and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green.”

The local parish church would be the focal point of the celebrations with Nativity plays and other festive traditions observed.

Feasting was of course a major part of the celebration. The humbler members of the community might treat themselves to a rare delicacy of some meat, cheese and eggs. On the menu for the local clergy and lord of the manor might be such things as Larks, ducks, salmon, even wild boar. At the other end of the spectrum was the royal court…

On Christmas day 1213, King John, spending the festive period at Windsor Castle, held a feast. The sheer quantities and logistics concerning the organisation of the feast boggle the mind. In charge was Reginald de Cornhill, a long-time administrator under King John.

We can only imagine the stress poor Reginald must have been under. With only around a week’s grace, he suddenly found himself with the task of finding,

“20 tuns of good and new ordinary wine, both French and Gascon, and 4 tuns (2 of red, 2 of white) for the king’s table. 200 pigs’ heads with all the pickled pork, 1,000 hens, 50 pounds of pepper, 2 pounds of saffron, 100 pounds of good fresh almonds and 15,000 herrings, as well as spices for making sauces, two dozen towels and 1,000 ells of linen for making tablecloths”.

Other officials were tasked with finding even more provisions, including another 200 pigs’ heads, 15,000 hens and 10,000 salted eels. They also needed to lay their hands on all the pitchers, cups and dishes they could find.

You might have thought, given the severe financial pressures John found himself under during his rule, that this sort of extravagance might have attracted some criticism! However, from a medieval perspective, displays of royal generosity were expected, indeed they a were a key part of medieval politics and in fact the chroniclers of the time approved whole heartedly with his largess. He was only doing what was expected of a medieval king.

The post A Medieval Christmas appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

December 10, 2020

The Gongfermor – Dealing with Medieval Sh*t!

(Trying a medieval “garderobe” for size at Lamphey Bishop’s Palace, purely for purposes of research you understand!)

Towards the end of the 14th Century, London with a population of around 30,000 defecating souls, had only 16 public latrines, known as “houses of easement”. However, many private latrines (privies) existed, and the local authorities had even started to regulate their placement and construction. Cess pits started to be placed in the back yard of houses or even under their cellar floors. The more sophisticated arrangements carried excrement from upper floors by means of a wooden chute, sometimes flushed by rainwater.

Just as today, the space where you did the business was often given a “polite” name. Some common ones being the ‘privy chamber’, and the ‘garderobe’. The more imaginative ones include the ‘draught’, ‘gong’, ‘siege-house’, ‘neccessarium’, and the ‘Golden Tower’.

As most cesspits were not watertight, liquid waste would drain away leaving the solids behind. Every two years or so, this solid waste would have to be removed. As you can imagine, the smell and fumes could become a problem. It wasn’t unknown for clothes to be hung nearby as the acrid vapours would kill any mites in them!

King Henry III, (who was King of England between 1216 and 1272) in a letter to one of his castle constables complained about a privy at the tower of London that smelled so bad he wanted it rebuilt before his next visit,

“Since the privy chamber…in London is situated in an undue and improper place, wherefore it smells badly, we command you on the faith and love by which you are bounden to us that you in no wise omit to cause another privy chamber to be made…in such more fitting and proper place that you may select there, even though it should cost a hundred pounds, so that it may be made before the feast of the Translation of Saint Edward, before we come thither.”

A “gongfermor” or “gong farmer” was the term used at this period to describe someone who’s job was to dig out and remove the waste. (“Gong” is derived from the Old English gang, which means “to go”). The solid waste collected had to be taken outside the city walls or town boundary and was known as nightsoil. After being dug out, the nightsoil was removed in large barrels or pipes, which were loaded onto a horse-drawn cart. The job of the gongfermor was certainly unpleasant (day in, day out, up to the knees or waist in excrement) and could be dangerous but it was also well paid.

The post The Gongfermor – Dealing with Medieval Sh*t! appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

November 18, 2020

Pick up some free reads…I often link up with other author...

I often link up with other authors to cross promote our books to a wider list of readers. We currently have a promotion underway for the next month or so where you can pick up a ton of free reads from new and established authors. If you’d like to explore whats on offer click here.

The post appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

Pick up some free reads…

I often link up with other auth...

I often link up with other authors to cross promote our books to a wider list of readers. We currently have a promotion underway for the next month or so where you can pick up a ton of free reads from new and established authors. If you’d like to explore whats on offer click here.

The post appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

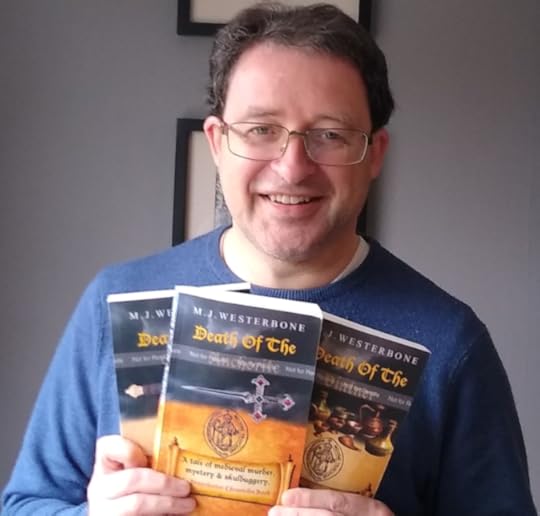

Death Of The Official – The Paperback Cover…

The last couple of weeks I have been preparing the formatted files and graphics of the latest book release for upload to the Amazon kindle store.

This time I’ve decided to do a simultaneous paperback release as well. As an independent author I pretty much do everything from the writing through to preparing the artwork. I could outsource most of this (apart from the writing of course!) but I’m a bit of a control freak and I like learning new skills as well.

I’ve really struggled with the paperback cover. Amazon has exacting criteria in terms of positioning all the cover graphics (so when its printed it actually looks correct and the text doesn’t get chopped off in the printing process). Anyway, the job is finally done now and I think it looks ok (see image above)

As I type this, I’m waiting for the proof copies of the paperback to come back from Amazon KDP.

Now to be honest, paperback sales are a fraction of eBook sales on Amazon but I think it’s nice to actually have a physical product as well. Some people will always prefer a real book over an eBook so why not cater for everybody if I can.

The post Death Of The Official – The Paperback Cover… appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.

A mortal blow to the back – a medieval skeleton

Watching TV the other day, I came across the “Bone Detectives”. It’s a program on Channel 4 here in the UK. The premise is “a team of scientists piece together the lives behind unearthed bones to find out their stories. Once a skeleton has been recorded, the bones immediately begin to reveal their mysteries, opening up a secret history of Britain.”

Watching TV the other day, I came across the “Bone Detectives”. It’s a program on Channel 4 here in the UK. The premise is “a team of scientists piece together the lives behind unearthed bones to find out their stories. Once a skeleton has been recorded, the bones immediately begin to reveal their mysteries, opening up a secret history of Britain.”

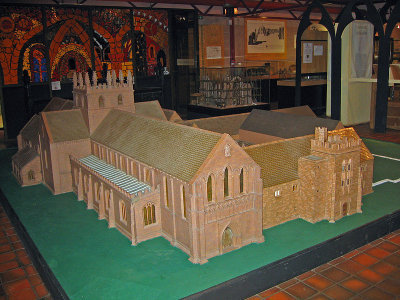

The series so far has been interesting (it’s well worth a watch) but this episode even more so as they were examining some skeletons found during excavations at Norton Priory. This is the remains of an abbey complex dating from the 12th to 16th centuries, which is only some twenty-five miles from where I sit typing this in northwest England. Now this part of the northwest is fairly industrial, where I live most of the towns really grew to prominence only in the Victorian period. The northwest went from being somewhat of a backwater in previous centuries to the heart of the industrial revolution. Heavy industry and medieval remains rarely go together, but Britain’s a place where you never have to travel far to find some hidden gem. My wife and I had a day trip out to Norton about six or seven years ago. The location of the ruins and museum is well hidden. The route takes you through a modern industrial estate and I was convinced we’d taken a wrong turn, even with the sat-nav guiding us.

The priory was an Augustinian foundation from the 12th century and was raised to the status of an abbey in 1391. As part of the dissolution of the monasteries, the abbey was closed in 1536. Excavation begin in 1971 and was to become the largest carried out on any monastic site in Europe during modern times. You can read more about Norton Priory here.

One skeleton discovered during the excavation shows signs of murder, with what appears to have been a sword blow to the back whilst the unfortunate victim was perhaps kneeling in prayer. It’s fairly likely the skeleton is that of Sir Geoffrey Dutton, a crusader knight. As you can image it was the ideal place to do some on-site research for story plots!

You will see Norton (or something based on it) in a future book in the Draychester Chronicles series, watch this space

October 31, 2020

Medieval Alehouses, Taverns, and Inns

In the late 14th century, when my books are set, alehouses and taverns would provide food and drink and inns would also provide accommodation for travellers. They make an excellent setting for the plot of a medieval novel. These were places where people met to socialise and talk. Particularly in towns, this made them cultural and political hot beds. Uprisings and mobs often had their origins in such places.

In England, inns were found mainly in towns and cities. They quickly became prominent landmarks and were usually located in a central position such as the town square, or in places where roads met. Geoffrey Chaucer of course immortalised these Inns in the Canterbury Tales, his Tabard Inn being a real hostelry in Southwark (the Abbot of Hyde originally built it so he and his good brothers had a place to stay when on business in London). But it wasn’t just pilgrims travelling to and from religious shrines who might need accommodation, there were a wide range of other travellers on the move, including merchants and court officials and monks travelling between religious houses. Inns could also be used for other purposes. “Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem” in Nottingham, allegedly dating from 1189, was said to have acted as a recruitment centre for volunteers to accompany King Richard to the Holy Land on crusade. By the 1400s many larger inns would have private function rooms. These could be hired by the local town guilds or for private events. Many inns also provided locked rooms and strong boxes for storage of valuables.

Taverns and alehouses could be found in the biggest towns to the smallest villages. In places like London taverns were often owned by brewers and vintners as an outlet for their wares, in effect having a monopoly on what alcohol was served.

In the countryside the alehouse was one of the main places of recreation for the villager. An alehouse might not be in a permanent location, villagers would drink at the house of any neighbour who had recently brewed a batch of ale. Like their modern counterparts, villagers would pass the evening drinking. Inevitably this could lead to accidents, quarrels, and all too common acts of violence. The coroner’s records of the period are full of alcohol-related accidents, mishaps, injuries, and murders. Then as now, drinking to excess could lead to more than just a hangover… again all material for scenes in my novels.

Before Henry VIII split with the Catholic church, many taverns and inns had religious names. So we have, “The Anchor” (a reference to the Christian faith), “The Cross Keys” (the emblem of Saint Peter), “The Mitre” (a bishops headgear) and “The Ship” (the Noah’s Ark). Then we have names that have a connection with the crusades like “The Saracen’s Head” and “The Lamb and Flag” where the flag represented the crusaders and the lamb Jesus. Taverns names after saints, “The Christopher”, after the patron saint of travellers, and “The St. Julian”, who was the patron saint of hospitality.

There were more straightforward names, “The Ball”, “The Basket”, “The Bell”, “The Cross”, “The Cup”, “The Garland”, “The Green Gate”, “The Hammer”, “The Lattice”, “The Rose”. “The Swan” seems to have been very popular, there were six Swan’s in London alone in the 1420s. Other London taverns in the same period were named for birds as well, including “The Crane” and “The Cock”.

Bolton lies about six miles from where I type this. It’s a place I know well, I used to work in the centre of the town and occasionally went for a drink in what also claims to be one of Britain’s oldest pubs, “The Man and Scythe” or as its modern sign styles it, “Ye Olde Man and Scythe”. The earliest recorded mention of its name is in a medieval market charter of 1251. The present building dates from the 1630s and has been extensively rebuilt since then. The only part of the original medieval structure is probably the vaulted cellar. The pub is reputedly haunted, and the cellar appears to be one centre of the activity. (The few times I sat in the pub’s “front parlour” I can’t say I noticed any spirits except of the kind you can drink). The name of the pub derives from the crest of the Pilkingtons, who were a powerful family during the period with various branches scattered across the northwest of England.

The post Medieval Alehouses, Taverns, and Inns appeared first on M.J.Westerbone.