Stephen Deas's Blog, page 7

September 22, 2014

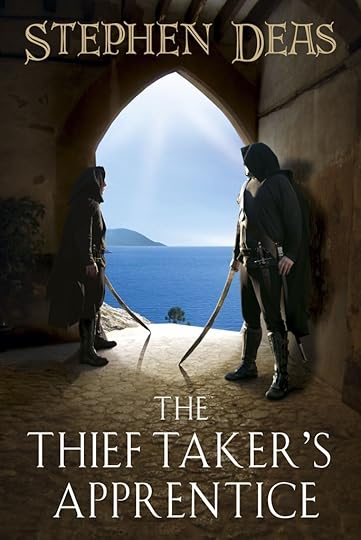

Giveaway from the archives: The Thief-Taker’s Apprentice (22/9/2014)

Berren has lived in the city all his life. He has made his way as a thief, paying a little of what he earns to the Fagin like master of their band. But there is a twist to this tale of a thief. One day Berren goes to watch an execution of three thieves. He watches as the thief-taker takes his reward and decides to try and steal the prize. He fails. The young thief is taken. But the thief-taker spots something in Berren. And the boy reminds him of someone as well. Berren becomes his apprentice. And is introduced to a world of shadows, deceit and corruption behind the streets he thought he knew. Full of richly observed life in a teeming fantasy city, a hectic progression of fights, flights and fancies and charting the fall of a boy into the dark world of political plotting and murder this marks the beginning of a new fantasy series for all lovers of fantasy – from fans of Kristin Cashore to Brent Weeks.

I suppose this only came out four years ago, but it feels like a very, very long time has passed, certainly long enough to have a moment of sober and self-critical reflection. The thief-taker’s Apprentice is certainly not the best book I ever wrote. Whether it’s the worst I suppose depends on where yout tastes lie. I happen to think that the sequel, The Warlock’s Shadow, is vastly better. It was my third (published) book and markedly differed from the first two in its focus. Where The Adamantine Palace sprawled across a dozen and more characters and locations, filled itelf with conspiracy and dastartdly deeds and sacrificed character development for pace and scale, The Thief-Taker’s Apprentice went the opposite way. It is a small, quiet, intimate story focussed entirely on two characters and set almost entirely within the walls of a single city. It was originally intended as a young adult story for boys, which takes a little edge of the sex and violence (although only a little). It certainly has its flaws (Berren’s ‘love interest’ is a flimsy two-dimensional character, intended as a reflection on the shallowness of early teen crushes and to be contrasted against the passions of his first real love in The Warlock’s Shadow; but of course, you don’t know that when you read Apprentice, and so it’s just shallow. And then there’s the single scene which switches the point of view to show the reader something that the protagonist simply cannot know, and that was really clunky).

On the whole I personally rate it as a 3-star book. It’s perfectly good, perfectly readable, nothing hugely special or memorable. It’s no Royalist or Crimson Shield, but it does start a story that carries on into Dragon Queen, which remains the best fantasy I’ve done. All of whihc probably isn’t much encouragement to drop everything and rush out and buy a copy, but fortunately you don’t have to, as I’m giving one away.

All you have to do to enter is comment on this post before the end of September 27th and I’ll randomly select a lucky victim (the usual deal if you’ve been here before). If you have a favourite historical, fantasy or SF novel which you think is a hidden gem but which no one else ever talks about and which vanished without a trace, I’d love to hear about it, but a simple “hi” will do.

This is open worldwide. Although though no one has yet complained about how long it takes me to get to the post office and post things, it can take a while and if you live abroad then it can take even longer. Sorry about that, but they do get there eventually. I am currently up to date with posting things.

September 15, 2014

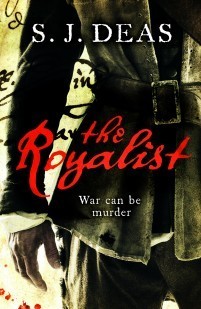

Giveaway: The Royalist (15/9/2014)

William Falkland is a dead man.

A Royalist dragoon who fought against Parliament, he is currently awaiting execution at Newgate prison. Yet when he is led away from Newgate with a sack over his head, it is not the gallows to which they take him, but to Oliver Cromwell himself. Cromwell has heard of Falkland’s reputation as an investigator and now more than ever he needs a man of conscience. His New Model Army are wintering in Devon but mysterious deaths are sweeping the camp. In return for his freedom, Falkland is despatched to uncover the truth. With few friends and a slew of enemies, Falkland soon learns there is a dark demon at work, one who won’t go down without a fight. But how can he protect Cromwell’s army from such a monster and, more importantly, will he be able to protect himself?

The Royalist comes out a week on Wednesday. What is it? A historical crime thriller set in the depths of winter during the first English Civl War. This isn’t my first forray into “straight” fiction – the Bulldog Drummond stories are historical adventures with no elements of the fantastic – but it’s the first one that’s a proper novel that will be sitting on the shelves of proper bookshops one day. For anyone interested, the opening chapter is available here.

I guess I’m well and truly back from my Summer break, and one thing I promised myself was that I’d start giving books away again once I was up to speed and caught up with the backlog. So with the last Bulldog Drummond novella now delivered and my Nathan Hawke alter-ego firmly in the writing driver-seat until I get back various editing notes, here goes – to celebrate its publication, I’m giving away one first edition hardcover copy of The Royalist, signed and dedicated however the lucky winner desires.

Is this a pretty crappy picture of the cover? Absolutely. But at least you get how SHINY it is (there’s a decent copy of the cover art here). Yes. SHINY and LOVELY. I’ve never felt a hardcover that felt so nice and silky. Though I might be biased.

All you have to do to enter the giveaway is comment on this post before the end of September 20th and I’ll randomly select a lucky victim (the usual deal if you’ve been here before). If you have a favourite historical period in which you’d like to see a novel set, or a historical novel you’d really like to see written, I’d love to hear about it, but a simple “hi” will do.

This is open worldwide. Although though no one has yet complained about how long it takes me to get to the post office and post things, it can take a while and if you live abroad then it can take even longer. Sorry about that, but they do get there eventually. I am currently up to date with posting things.

The Royalist – chapter one

Chapter One

Three times they tried to kill me. They came for me on those blasted northern moors and I lived. They cut swathes through my fellows at Edgehill and somehow, deep in dead men, I came through. They routed my company outside Abingdon and cornered me in the thick of night when I had nowhere to run to and nobody to watch my back. Yes, three times they tried to kill me.

Third time lucky.

I strained to see. There was no window in the cell but somewhere there was candlelight and it was enough to show that I was alone now. There had been three others in here with me when I closed my eyes but it was no surprise they were gone. They were Irishmen, all three, and I found out long ago what they do to Irishmen here. Sooner or later the same was coming for me. I found myself bewildered that I’d slept through it but felt little else save to be all the more sickened at how far I’d fallen. I’d listened to those men cry and talk of the homes, the families they’d left behind, lovers and wives and sisters and sons. Now they were gone and I couldn’t even remember their names. That’s what they bring you to in a place like this.

I rolled onto my side and sat cross-legged in the gloom, picking tacky damp stalks of straw from the rags that were left of my clothes. I had no doubt that I stank. The cells festered with sweat and filth and urine but I’d been here so long that I didn’t notice any more. I thought of my wife, my beautiful Caro, of the scent of her hair when she stood close with her head pressed to my chest. I waited for the shudder of loss and longing to come but it didn’t. I was nothing now but numb.

I didn’t suppose it mattered. I wasn’t getting out of there alive and all those promises I’d made to the three Irishmen, to take away messages for wives and brothers and sons, well, we’d all known they were empty words. Sometimes you say what you’ve got to say and even if the other man knows it’s a lie, he’s still glad to hear it. Sometimes, flying in the face of everything around us, we choose a sliver of hope. I was never good at that.

I don’t know how long I sat there. I didn’t draw myself up when I heard footsteps. If they came for me today then I wouldn’t sob or scream or rain a thousand curses on their heads like some I’ve known, but I wouldn’t stand up for them either. It’s come to be that that’s what they expect, that we stand for them. They’d have us doff our hats as they led us to the gallows, if hats we had.

My jailer appeared as a darker silhouette against the deep gloom of the distant candlelight. He jangled his keys. He wasn’t the man I knew when they first brought me here – that man was long gone, probably to the same war that had kept me from home for five long years. The soldier who appeared before me instead was scarcely more than a boy, no older than the son I was certain I’d never see again. He fumbled a jangling ring of keys until he found the one to fit my lock. A faint smell of gunpowder reached across the air between us, sharp and sulphurous. A thought flashed across the backs of my eyes: that I was still strong enough to run this boy down. The gate to my cell squealed back but I didn’t move. It wouldn’t serve any purpose. It just felt good that that part of me hadn’t withered away, no matter how long they’d kept me alone in the dark.

‘Falkland,’ the boy said. His voice had barely broken.

I looked up. Nothing more.

‘You’re to come with me.’

So there it was. My time. When the boy decided I wouldn’t thrash about and grapple him, he strode in – purposefully, as he must have been taught – and fiddled with keys again. He left my ankles and wrists manacled but unlocked me from the grille and bade me stand. I stayed sat where I was just long enough to make him think he might have to call for his masters and then did as he asked. I had no interest in causing trouble. He was just a boy. Nothing I did was going to change things now. I’d be dead within the hour and in a way it would be a relief. It’s a bitter war whose purpose is lost to those who fight it. It has a will of its own, I think. It grinds men to husks and those are the lucky ones.

I walked with the boy behind me along rows of cells just like mine. Some were open-faced with grilles and I could see the men lying in scarred heaps inside. I’d shared conversations with some of these fellows though most were too deranged to remember. I tried not to look but I couldn’t stop my eyes from being drawn. One man lay stretched across the cold stones in a horrible paroxysm of grief. He dead-eyed me, his tongue lolling out. I saw another man lay underneath him, already dead.

Somebody shrieked from the cell opposite, startling us both. I looked round. Chains rattled against bars. Even if I didn’t hear a word, I knew the other prisoners were singing me on my way. There was only one exit to a place like this.

We reached the end of the row of cells and climbed a stone stairway to the next. The steps were old, chipped and uneven, thinly coated in a wet slime of mud and dung, trampled back and forth by the boots of our jailers. A fresh reek of rot and offal rose from them, climbing through the stink of the prison. Even when we came to a passage where cold daylight streamed in to dazzle me, it still felt as if we were six feet underground. The air remained stagnant and rank. I began to think this wasn’t Newgate at all as some of my fellow prisoners had said. Perhaps we weren’t even in London.

We came to a gate where two turnkeys sat. The boy instructed me to stop. ‘I’m sorry, Falkland,’ he said.

‘Nothing to be sorry for, son. It’s not you who’ll pull the lever.’

He paused as if he didn’t understand.

‘I have to, sir . . .’

Sir? I must have misheard. He probably meant cur.

The boy produced a hood stitched out of an old grain sack from a loop on his belt. The sight of it killed any last flickering thoughts I might have had of some miraculous escape. That hood and I had become friends these last long months. I’d been wearing it when they brought me in here and now I’d wear it on my way out too. I managed a smirk. It was the sort of neat pattern by which I once wanted to live my life.

‘Do what you’ve got to do, boy. But I’d rather look my hangman in the eye. That’s a mercy the King used to grant every man he condemned, no matter what he’d done.’

The boy mumbled something I didn’t hear and dropped the hood over my eyes. It tightened with a drawstring around my neck. I heard the gate lift and we were on our way again. It was difficult enough to move with my ankles still shackled, so the hood didn’t make much difference. I felt daylight strike me for the first time in months and, even under the grain sack, it was brighter than any light I’d ever seen in my cell. I knew it was beautiful, as was the wind that touched my skin, the air bitter cold. In my cell I’d judged the month to be November: now I wasn’t so sure. This felt more of a January or February chill. However we tried, we all lost track of time in the relentless gloom.

I stepped where I was told. I slowed when I was told and stopped when I was told so that gates might be opened and steps pointed out. The boy tugged me along like a dog on a leash. I didn’t resist. Wherever we were, the day was eerily silent. I’ve seen more than my fair share of public executions and never felt one as miserable and unwatched as this. I began to climb what I supposed must be the gallows steps and didn’t hear a single scream, a single cry, the smashing of a single stone thrown by some onlooker in the crowd. Underneath the hood I started to smile. I couldn’t suppress it. Had it finally come to this, then? Not even the commonfolk could bear it any more? Usually they turn out for any spectacle at all, no matter how grisly, but today the will of the people was being heard and it sounded like nothing I’d ever known: it sounded like silence. Had they had enough at last? Was it coming to an end? I’d heard as much but prison rumours are wild things, whole stories grown from a single misheard word.

‘Watch your head, Falkland.’

The boy pressed his palm on the top of my head and bade me stoop down low. I supposed they were fitting me for the rope and I was pleased to find that I wasn’t afraid. I was ready for this, as ready as I could be, even as the last regrets and a final memory of my Caroline filled me. A hand pushed me forward. I stumbled and almost fell as the boy pushed me down into a rough wooden seat. I felt him withdraw and heard a door shut close by. A horse whinnied.

Wait. What? This was no scaffold and gallows – was I in a carriage now?

At once my calm was gone and a fear took me in its place. I whipped my head left and then right. I’d been ready to hang, ready to die, but not ready for this. I felt certain that I was not alone, too, but I would have known it if the boy had climbed aboard behind me. Someone was already here then. I tried to lift my hands but now the boy had locked them down. A horrible panic churned deep inside me. I heard a heavy breath and then a stench crept into the air inside my hood, the like of which I’ve only known from men on starvation rations whose very bodies have started to eat themselves. The sickly smell came through the grain bag hood and wrapped itself around me. I had no choice but to breathe it in.

‘Sit still, Falkland.’ I didn’t know the voice. It sounded deep and musical: a thespian or a minstrel, some courtly fool too cowardly ever to fight. I imagined it might belong to a jester, except the Puritan men who held me would never entertain such a thing.

‘Who are you?’ I knew then how afraid I was from how desperate I was to know. A condemned man can come to peace with his fate; but a man who doesn’t know it might kill himself with worry.

‘You might count yourself fortunate, Falkland, that you’re even here to ask that question.’

‘You didn’t answer.’

‘It matters little,’ the syrupy voice returned. ‘I’m an escort. Nothing more.’

‘Escorting me where? I was supposed to die today.’

‘Were you?’ This must have amused the man for he let out a little chortle. ‘You were supposed to die every day for the last month. Fortune smiles on you, Falkland. When we heard who you were, we were intrigued.’

Who I was? I was nobody. I wasn’t even a commander. A mistake, then, but now some intelligencer wanted to ask his questions before they hanged me, was that it? Damn it but I wasn’t even with the King, not really, not through anything other than blasted chance. Hundreds and hundreds of men out there were dying for their ideals but there were thousands more like me, dying just for the sake of dying. I was tired of this war long before it even began. I just wished they’d hurry up and get on with it – let me die for somebody else’s crusade and then let me rot in peace.

I sat in silence. The other man didn’t make a sound but sometimes you can hear a smirk.

‘Where are we going?’ I asked. I knew my questions must be futile but I felt compelled to break the silence. At least, for a few seconds, it saved me from breathing his hideous breath.

‘Settle down, Falkland. You’ll find out soon enough.’

The carriage rattled on. I had no idea where we were going but I knew we hadn’t left the city. The air was fresher than I remembered of London from five years before, but that was only because the King held Newcastle and so there wasn’t any coal. People would freeze on the streets this winter. All the same, I could hear the city sounds and smell the city smells. I fancied we’d come to the river and were following its banks because we stopped threading through narrow streets and I could hear seagulls. Their screeching reminded me of home, of those Cornish beaches where the waves would thunder and crash, and I felt a horrible flurry of joy – horrible because I’d abandoned both hope and joy long ago. To know it could reappear so suddenly, so violently, felt like a betrayal.

I heard bells then, and not the plaintive pealing of bells from a country church – I’ve heard that sound too often, as if the church towers themselves are crying out against the marauders ripping out their altars and setting fire to every icon. No, these bells were more powerful, more strident and they were getting nearer. They were the bells of Parliament, of St Stephen’s Chapel.

I heard the man beside me shuffle. He must have known, now, that I had guessed.

‘Why?’ I asked him.

‘Your questions will be answered, Falkland.’

‘You’ll answer them now!’ I was so desperate to understand why they’d bring me all this way, and for what purpose, that against my own will I lashed out, but the chains only snapped me back with a jolt that shuddered right through me. Bones jarred and old wounds started to shriek. My heart pounded in my breast.

‘You exert yourself too much for a man who’s been shackled to a rail for four months.’ There was a sneering disdain to the voice.

‘Four months? Is that all it’s been?’ Four months. Barely November. I wasn’t as wrong as I’d first thought, though the chill of the air remained as of the very depths of winter.

The carriage slowed to a halt. I felt it turn and cut a tight circle. The horses whinnied and then we were still. The man beside me stood and bustled past, dropping out of the door on my right. ‘It feels longer, doesn’t it, Falkland?’

He sounded contrite, as if he too had suffered similar deprivations. Hatred would have angered me less. I wasn’t expecting him to feel anything for me at all. ‘You have the wrong man,’ I told him, though I knew I was wasting my breath. His hand grappled with mine and in that way he steered me to the ground. Somewhere above us the pealing of the bells went on. It was, I had counted, noon. In my cell I had made it midnight.

‘It’s almost over, Falkland.’

There was a terrible irony in that. I had thought it almost over from the very beginning.

August 26, 2014

July 21, 2014

The Sin Eater (Unexpected Journeys, 2013)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The story “The Sin Eater” appeared in Unexpected Journeys in2013

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Sin Eater

Servants usher Sola into a sterile stone antechamber. They whisper to one and other, solemn and funereal. Sola watches their dead eyes, their pallid skin, the expressionless rictus of their faces. She’s seen it all before, the whole spectrum of it, the wild wailing abandon that comes from watching a cherished life crushed to an unexpected end, the tearful smiling farewells to a much-loved elder, the tomb-like masks of servants waiting for relief from a master who won’t be missed. The death she’s come to witness today has a savagery in the air behind its careful silence. Fear and envy and outright hatred boil together, their parts changing every hour. It glides over her like water over feathers.

The antechamber walls are bare, stripped. Faint outlines show where paintings and tapestries once hung. There are three doorways – the one she stands in; the next a battered wooden thing that once had a hanging in front of it; the last much grander, although its gilt has faded and the dark hardwood shows its age. An elderly servant with an etched face sweeps his arm with reverential ceremony, guiding Sola forward. All their motions are careful as if they’re afraid to disturb the air, as if that might hasten their tyrant master’s demise. Sola mimics their delicacy. Some of their hostility is for her. Sin-eaters are strange men and even stranger women, feared and revered, blessed and cursed, holy and damned both at once. Some say they are half demon. Others that the blood that flows in their veins has been touched by the essence of angels. The suppressed anger, though? They hide it badly. The man she’s here to save truly deserves to go to Hell.

Inside the bedroom the old man they all hate lies sleepy-eyed in bed. Sola looks him over. She’s never seen this man before but she’s heard of him, oh yes. Even knows his true name though he never uses it any more. She decides she will call him Magus, a reflection of the darkness at his core. She’ll call him that and come to no harm for it, just as she might call a king a fool to his face and feel no fear of the gallows. Sin-eaters stand outside judgement. Some have been murderers, rapists, plunderers and pirates, the very worst kinds of men and women – but they are always saints, outside any law but God’s, for to kill a sin-eater is to take on her sins.

Sola gathers herself and sits beside the old man’s bed ready to guide him to Heaven. The Magus has a blanket pulled up around his armpits; it was beautiful once, made by the weavers of Belasas a thousand miles away. A blanket like that costs more than a pair of good racing horses, probably more than everything Sola has ever owned, but this one before her is threadbare and stained. The old man’s head and shoulders are propped up by a wedge of fat goose-down pillows. His arms lie over the top, limp and pressed against his sides. His face is speckled with the marks of age, his hair thinning and white. He’s already ancient. Time, always fickle, has turned its back on him.

Two other men wait on him. A thug-faced soldier in a brigandine coat with a rapier on one hip and a pistol on the other, and an oily-skinned snake disguised as a man, preening his thinning hair as he stands in his fine red silk robes. The oily man speaks. “I am Eserleri, chancellor of Elsporth. If you have needs or grievances, please bring them to me at once.” He bows with an obsequious smile and an expansive flourish.

Sola nods. She looks from him to the second man, the soldier. He’s feigning boredom and a dull lack of interest but she sees right through him. Underneath is something else. His eyes don’t leave her and his gaze is hard and cold. If he had the freedom, she thinks, he would cut her down right here.

“Jarkko will keep you honest.” Eserleri keeps his smile, bright and wide with malice. “Jarkko is a Graved.” When the snake says that the solider will keep her honest, he means the Graved will never let her out of his sight outside this room until the Magus is dead. He’s there to see she doesn’t secretly vomit up the sins she’ll eat and bury them. No one knows what happens then. Is the sin-eater cheating God and Heaven? Do the sins simply return whence they came? Do they vanish, lost from the great divine account? Where do these orphan sins belong and who will be judged for them? Only God knows the answer and so the Magus is taking no chances.

Eserleri bows and withdraws, slowly and with reverence. The Graved Jarkko follows with a swagger that says he doesn’t give much of a shit one way or the other about any of this and doesn’t want to be here. The Magus hisses and waves his skeletal hand and then, at last, looks at Sola. His eyes crawl all over her. There’s meaning in that look. “So Jarkko finds me a girl,” he says in disgust. “Their bile is always there, spewed out behind my back though they’d never dare show it to my face, not one of them. A girl.” He spits out the word.

“I am a sin-eater, Magus,” answers Sola.

“And I’m dying.” He glares at her as if his very look might flay the skin off her face and so make her more to his liking. She holds his look, calm and steady. She’s seen a lot of old men on their deathbeds and a lot of old women too. Some shower her with words of gratitude. Others hate her.

“Death comes to everyone,” she says. “Kings and peasants, all must pass away.”

She bows her head and tries to hold a sombre moment and dangle it between but the Magus only frowns and scrapes his throat and spits a smear of phlegm onto his once-priceless blanket. “That supposed to cheer me is it? My death doesn’t come to just anyone.” He taps a bony finger to his skull. “There’s a beetle in my head, girl, and it’s eating me.” He bares his teeth and hisses again. When Sola doesn’t flinch, he cocks his head. “Did you hear? I said there’s a beetle eating the inside of my head!”

“The Lord Ambassador who preceded you,” Sola says quietly. “I heard he died the same way.”

“Everyone knows that story.” The Magus coughs a little laugh. “Does it make your stomach crawl, girl? I can feel her scuttling around in here.” He taps his skull again. There’s a twisted affection in his words. She’s seen it before, once from a farmer gored by his own bull and once from a duellist beaten and killed by a blade that dazzled brighter. The beetle in the old man’s head has the better of him. It has his respect.

“How long do you have?” asks Sola softly.

“She’s eating away at me now but she won’t kill me on her own. When she’s had her fill she’ll lay her eggs and die. Thousands of them. When I stop feeling her little taps and knocks scraping around in there then I have hours before they hatch. That’s when it happens. Do you have that long, girl?”

He calls her girl as though it matters, as though she should feel somehow lessened by it. Like the hostility of the servants, it slides away like water over oil. The old man will be dead soon and so she sets his unkindness as a railing against that end. “I have as long as you require, Magus.” She might ask whether the old man thinks he’ll have long enough for all the sins he’ll be spewing out of him but that doesn’t strike her as a very holy question, and for now she has a mask to wear. “Have you ever witnessed a sin-eating, Magus?”

“Of course not.”

“It’s best to start with some small thing so you understand what happens.” She bows her head. A sin-eating is a private thing, like confession, though she can’t imagine the Magus paying any heed if that ever got in the way of what he wanted.

“I’ve been unkind to my horse.” The old man laughs and then stops abruptly as Sola passes a hand over him. His eyes fly open; he jerks upright and coughs and retches and at last spits out a stone. He stares at it in wonder, the size of a holly berry and as black as the hollow eye of night. “God in Heaven, girl, I thought you’d killed me,”

Sola picks up the stone, slick with the old man’s spittle. She holds it between them. “This is the sin of being unkind to your horse,” she says, quiet and gentle as a whisper of autumn. “It is taken from you.” She places the stone in a silver bowl and rinses it with water, then dries it with a small square of white silk. She puts it in her mouth and swallows it down with a swill of herbal elixir made with ingredients bought from the Elsporth apothecary the day before. “I have eaten your sin, Magus. You may choose what you will give to me and what you will carry with you to bare before God. I will eat whatever you offer.” She meets his gaze again, level, ice for ice. “It is, as I say, best to start with something small.”

“Oh you can have all of it, girly, every one of them. The devil might want me but I mean to disappoint him.”

Sola nods. She takes out a book and flicks to an empty page. As the Magus speaks, she begins to write.

The Lord Ambassador – the Magus as Sola calls him – lives in a fort atop a thrusting rocky outcrop called Biter’s Drop. Jarkko, who is quietly curious about the name, folds his arms across his chest and pretends to doze. A sin-eating is a private business but when the sin-eater leaves the old man’s side, Jarkko will never let her out of his sight until one of them dies.

In his mind’s eye he eyes up the innards of the little fortress. An old lookout tower rises from one corner, wrapped in a sheath of vines that reach almost to the top in their effort to drag it down. Elsewhere a collection of rickety wooden sheds press up against the walls: a kitchen, some hanging shacks and storehouses and a lean-to that passes as shelter for both servants and travellers. A tight road winds reluctantly from a shabby gatehouse down to the river below, too steep and twisting for a cart or a wagon. At the end of it, Biter’s Drop overlooks the Charred river and the little market town of Elsporth and then a thick wall of forest where the Graved live.

Elsporth still bears the scars from the last time the Graved came. Six years he’s been here. Six years since he came across the Charred with his kinsmen and gave them away. He’s waited a long time since then and he still doesn’t know how Biter’s Drop took its name, who bit whom and who fell or was pushed. Someone, once long ago. Probably he’ll never know.

He thinks of his prostitute who waits in Elsporth. Thyronis is slender and often mistaken for a woman. Occasionally he dresses as one too. Jarkko, on the other hand, is a brute. With his hair hacked short and his scarred face, most people see a Graved and nothing else. He carries a double-headed axe across his back which is how it came to be that he once rescued Thyronis from a gang of sodomites who didn’t seem to care much what he was under his dress. Or perhaps he needed rescuing because he was a thief. He still is. Right now, Jarkko imagines Thyronis looking up at the keep and its tower, his head full of thieving thoughts.

A servant comes through carrying a pitcher of milk. He goes into the bed-chamber and quickly comes out again.

“I’m hungry,” says Jarkko, but the servant only laughs and goes through the low wooden door. A curtain hangs half torn from the roof beyond. There’s the unmistakable sound of piss into a pot. The servant brings with him the stale smells of smoke and candle fat that remind Jarkko of the flop-house in Elsporth: a room with a hearth that hasn’t seen a fire for months, a table that wobbles, a handful of stools that aren’t quite straight and a single chair. He imagines Thyronis pacing back and forth, looking here and there, searching all the nooks and crannies for lost pennies and those cheap bone-carved loops and needles that the people here like to wear in their hair. When he closes his eyes he imagines hearing little yelps of delight whenever Thyronis finds one.

The Lord Ambassador would have Thyronis executed by shoving a red-hot iron spike up his arse if he knew of Thyronis’s tastes. It’s a dull, distant tyranny. Six years he’s been here. He still doesn’t know how Biter’s Drop took its name but he knows by now that the Lord Ambassador deserves eternal damnation more than any man he’s ever known. And now he must see to it that this sin-eater guides the old man to Heaven.

Sola is writing in her book again, tiny and precious and scribbled in code. Every sin she eats must be written down to be spat out again one day lest she be cast into Hell, fodder for greedy Lucifer. It’s not a life for everyone. At least priests with their confessions don’t damn themselves by what they do.

She looks up. They’re done now with how the Magus treats his servants no better than his horses, how he had one whipped to death one day for no better reason than he felt like it and wanted to set an example. There’s the matter of the war, half a decade back now when the Graved came across in boats and sacked Elsporth and the Lord Ambassador shut his gates good and tight and did nothing until the raiders tired of their sport. He let them have their fill. It was the start of an invasion, he claims, but he gave them Elsporth and set them to fighting among themselves and the grand war that might have been came instead to nothing. Eventually they settle on the sin of ‘acting in his own interest over that of the common folk who looked to him for protection.’ The Magus is reluctant but spits it anyway. Better safe than sorry. The stone he coughs up is the size of a small plum. It takes some swallowing.

“What about greed?” Sola suggests. Greed, lust, gluttony, sloth, wrath, envy and pride, every sin-eater learns them. Abandoning his people to die under sword and fire might be called sloth, though Sola prefers the older term of acedia: an abandonment of duty, a neglect of one’s purpose and talent.

“Greed?” the Magus laughs. “You’ve heard the stories then?”

Hidden under her cowl, Sola bites her lip, forcing herself to be still and quiet. A good sin-eater coaxes the sins out of the man she means to save, one by one until all are gone and nothing more. Judgement is left for God.

When all the Magus gets is silence, he adds a little sourness of his own. “Very well. Yes, I murdered the Lord Ambassador Yardis, my predecessor. I murdered him for his wealth. There. Happy?” This is a rumour so widely spoken as to be a part of local history, a thing taken as fact. It’s why Sola has come here, to hear this. But still, behind her mask of bland acquiescence, the admission jolts her more than she’d expected. The horror isn’t so much that he did it. It’s how.

“Was it simple avarice, Magus?”

“What’s it to you, girl? I did what I did. The reasons don’t matter.”

Sola bows her head, hiding her expression. It’s hard enough to control her voice, never mind her face as well. “I would send you to God with your soul cleansed, Magus. Speak as much or as little as you wish. The saints will judge you for that which you still carry when you stand at Heaven’s gates before them. It’s for you to choose what you leave behind.”

The Magus shifts, uncomfortable but caught. As much as anything this is why he sent Jarkko to find him a sin-eater. Mere confession never feels enough. “Look about you, girl. What do you see? A little rural province too far from the Holy Court to attract attention. A thriving port with more boats coming in than you might think. Out there in the forests on the other side are the Graved, too busy fighting each other to offer much of a threat. And a Lord Ambassador clearly taking half of what should be sent to the Holy Father for himself? I came to Elsporth twenty years ago as a listener, as the eyes and ears for His court, and I saw the same. I told Lord Ambassador Yardis that he was a thief. I told him I’d say nothing if he gave me a piece of what he was keeping . . .”

Sola passes a hand over the Magus, who, startled, coughs up the obsidian sin of blackmail. She washes it in her silver bowl, dries it, swallows it with a mouthful of elixir and makes a note in her book. The Magus has coughed enough wickedness now that he barely breaks his stride. “Is that the greed you wanted?” He sinks back into his bed and stares up at the ceiling. He has a strange look in his eye, the first time Sola has seen any real emotion through all the litany of his life. A remembering. A regret, is it? A tightening of the lips betrays an old anger. “He cast me out,” says the Magus. “So after I returned I sent him a gift. Sugared dates from the homeland I left half a century ago, laced with the eggs of my little beetles. When he ate them they hatched into larvae. The larvae burrowed into the flesh of his gut and crawled through his body into his head. Once they were there they started eating. I’m told it took him an hour to die; that after he fell he was still for a while and then his face began to twitch and his head jerked and a swarm of beetles erupted from every orifice, from his nose and mouth and ears and eyes. When they cut him open his skull was empty. Scoured clean.” The same story that everyone knows for a hundred miles. Beetles like the one the old man has inside him now. Sola bites on the irony as she passes her hand over the Magus who spits out the sins of greed and murder. She cleans and swallows them, drinks and writes them in her book but the Magus is shaking his head. “Seven others died, sin-eater. His taster, who didn’t die quick enough to save the rest of them. His wife and his brother, two children and two of his guests.”

The Magus coughs seven more times. Sola swallows the seven black stones he spits out.

“After the Graved razed Elsporth I sent a few more gifts to their king and their barons.” The old man winces. “And there’s the sin of vengeance for you, girl, and wrath as well.” He stops and stares at Sola long and hard and then smiles a bitter smile. “All the wealth you think I have? Gone. There’s nothing, sin-eater. All I have are my beetles.” He fluffs his goose-down pillows. “I bought enough to kill every Graved between the river and the sea. I sent my presents to the court of every baron I could name. All dressed up as gifts from one to another and certainly not from the Lord Ambassador of Elsporth. I don’t know how many of them were taken. A lot. Ask Jarkko if you like. I’ve noticed they’ve been busy killing each other these last few years. Very little trouble to me at all. What sin is that? I was protecting my people. Doing my duty. I have no idea how many of them died. Is it a sin at all?”

Sola passes a hand over the Magus. “For all the Graved.” The old man coughs and spits out a gobbet of wet black sand. Hundreds of tiny grains, perhaps one for each man dead. They both look at the sand staining the once-priceless blanket, then Sola scrapes up as much as she can and swallows it. She fastidiously licks her fingers. Grains are left stuck in the soft weave. More cling to the Magus’s lips and inside his mouth. She passes him a pitcher of milk and a cup. “Get every grain and spit it out. Every one you miss you’ll carry with you to the gates of Heaven.” While the Magus does this she gently pulls at the blanket. “How much time do you have?”

“I still feel her crawling around in there. She hasn’t laid her eggs, not yet.” The Magus looks at her. “Come again in the morning.”

“Is it quick, this death of yours?”

“Quick enough. Once her eggs hatch they’re voracious little things.”

“You know the price for a sin-eating, Magus?”

“You want my treasure? I told you I don’t have any.”

“It’s no use to you in Heaven, nor in Hell.”

“What remains is yours when you’re done if you want it.” He laughs. “I’m sure we can find you something.”

Sola takes the blanket and carefully folds it, making sure that none of the grains of black sand fall out. She carries it from the Magus’s bed, through the antechamber, down the stone stairs into the hall below and to the tiny room she’s been given while she stays. The servants leave her alone and keep out of her way. The Magus’s watcher, Jarkko, falls in behind her. He moves too quickly, giving away the anxious burning in his thoughts. Now and then he simply stares as if looking deep into the past or perhaps the future. Each time, Sola sees the transformation of his face, the ugly twist of hate and murder that lights with bloody fire in his eye.

“Tomorrow,” she says as she watches him. “It’ll all be done tomorrow.”

Jarkko grunts and follows her into her room. Sola lights a lamp and prays and then with painstaking care sucks out every last grain of sand from the blanket. When she’s done she cuts out the piece now stained wet with her own saliva and eats it. Best to be sure. She drinks milk to force it down and then takes another draft of her elixir. It’s unusual for a sin-eating to take so long or for there to be so much. All the old man’s sins make a weight in her stomach. She’ll have cramps in the morning, bad ones. She lies for a while, staring at the ceiling while Jarkko sits silent in the corner, watching. A sin-eater must grow used to sleeping like this, with eyes looking over her. Eventually she goes to sleep.

Jarkko sits, sleepless and restless. In the dead of night he hears shouts in the yard and screams and a clash of arms. The Magus isn’t yet dead and already his men are fighting over the spoils. It calls to him, urging him to make an end to this.

Sin-eaters carry the secrets of the men they save. Some travel with bodyguards to protect them from devils and plunderers who would steal them. Not this one. Silently Jarkko draws a knife from the sheath at his belt, ready to kill this sin-eater who will save his master. But he stays his hand. This woman has eaten half the old man’s sins. Slit her throat and they become his. He doesn’t know how he could live with that.

Sola hears the commotion too, the screams and the shouts, a quiet for a while and then a hue and cry of alarm and more fighting. She doesn’t move. She watches Jarkko through half-closed eyes and sees him draw out the knife and pause and slowly slide it back. She sees the anguish in his face and wonders what it can mean.

“You can go if you want,” she murmurs but he shakes his head. She lies back and listens, in the quiet moments, to the rhythmic tread of boots back and forth on the wooden boards outside her door.

She’s asleep again long before the commotion subsides but before dawn she wakes again with a gasp, stricken by crippling pain. Stomach cramps. Vicious ones, every bit as bad as she feared. The sooner this is done the better. The manor has a different feel to it today. There’s an emptiness as she returns to the Magus and Jarkko tramps wordlessly behind her, a sense of the forsaken. She doesn’t see a single servant as she walks to the Magus’s bed. The smells are wrong, the air adrift with the scents of unlit fires and cold empty bread-ovens. Everything is absence. The room where the Magus lies is near-lifeless too. A plate sits beside his bed and a half-empty pitcher of milk. The Magus regards her. His eyes glitter with hate.

“You did this.”

Sola gestures calmly to Jarkko. “Your watcher never left my side.”

The Magus stares on until the venom transforms to something else, something more bitter still. “I had a wife for a while. She bore me three heirs. I was cruel to them all. I beat them. She despised me. I knew she had a lover and knew she planned to run and I knew the Graved were coming. I sent her down into Elsporth the morning before the Graved crossed the river. I didn’t mean for her to take my sons. I didn’t know until it was too late. They were all murdered amid the slaughter the Graved wrought. I brought that down on them. There. The heart of my vengeance. Take it.”

Sola passes her hand over the Magus but nothing comes. She shakes her head. “Grief is not a sin, Magus. I cannot take it.”

“My servants are looting my carcass before the light fades from my eyes.”

“At the gates of Heaven, all counts for naught but that which you carry on your soul.”

“Lift your hood, sin-eater. Let me see you.”

Sola hesitates. Her cowl comforts her and keeps her features half-hidden in shadow and hides her emotion. But the Magus is looking hard and won’t be moved and so she draws it back.

“You have a resemblance to Yardis, you know.”

She imagines her eyes all a-glitter. She lets out a grimace of pain, screws up her face and clamps a hand to her stomach. “Forgive me, Magus. The cramps have the better of me for a moment. I . . .”

“He had four bastard boys from three women among his servants. I found the women and hanged them. The bastards were drowned in the river.”

When the cramps ease, Sola passes her hand over the Magus seven times, one for each murdered woman and one for each child. The Magus spits six black stones like grapes onto his blanket, another gem from Belasas but even older than the first. The seventh stone is smaller. The two of them stare at it.

“Why aren’t they the same?” asks the Magus.

Sola takes the stones and rinses them, dries them and one by one swallows them each with a sip of her elixir. She looks at the last before she eats it and then writes them in her book. “I don’t know, Magus. Perhaps one of them didn’t drown after all.”

The Magus spits in disgust. “Then I should hang the man I sent to do it except I had rid of him long ago. But if one of them didn’t drown then why is there a stone at all?”

“There is sin in the intent, Magus.”

“Oh there’s sin in everything isn’t there, girly? Perhaps some lucky bastard out there will raise a toast to my passing, then. Will that be a sin too?”

Sola doesn’t answer. She’s been taught that God judges men by their deeds, not by their thoughts.

After a moment the Magus sighs and looks away. “Shall we be on with it, then? Would you hear of the other men I’ve had killed?”

She must. It’s what she is and she’s eager to be finished. It’s hard, knowing what this man has done, not to despise him.

The Magus speaks. One after the other, a procession of murders and betrayals and with each one the old man spits out a stone and Sola swallows and writes it down. The cramps grow steadily worse. She’s sweating and pale and her voice starts to shake. But with each stone she drinks nevertheless. Until the Magus stops.

Outside the door to the Lord Ambassador’s room, Jarkko paces. He’s hungry, waiting for breakfast and impatient but no servants come to their master’s chambers today. He hears commotions here and there, voices off, shouts, the clatter of falling bowls and the shatter of broken clay.

“I’m hungry,” he calls, but no one comes.

He wonders if it’s too late, if the sin-eater has made his master pure. Perhaps he could run and kill the old man before she’s done. Suffocate him with one of his goose-down pillows. The Magus deserves his Hell, he thinks. But Jarkko is a godly man and murder is a sin.

“It’s coming, girl.” When the old man finds his voice again it’s cracked and has a tremor to it. “I don’t feel her in there any more, crawling against my skull. She’s laid her eggs and died.” He shivers and speaks more quickly now, driven by a fear that Sola has heard so many times before – the fear of dying with a weight on your soul, the sudden recognition of the ticking clock with its hands so very close to midnight. The old man slumps back when they’re done, exhausted and spent. He is, at last, pure. She’s done this. She’s swallowed his wickedness, all of it. She feels the weight inside her, the stones grinding in her belly.

“Is there more?”

The Magus shakes his head. “Go. Take your payment. Take whatever you want, whatever is left. Jarkko will show you.”

“Your soul is free, Magus. Heaven awaits.”

She leaves him then, though she’ll come back for the end because she always does. Jarkko follows like a faithful hound. She stops by the kitchens but there’s no one there and so she takes an empty pail and goes out to the yard to soak up the morning air. The watchtower door hangs open. The gates in the wall as well. Three guardsmen lean beside them, nervous, agitated and frightened. Two bodies lie in the middle of the yard, testimony to the bloody murder of the night. A wave of cramp doubles her over. She staggers and sinks to her knees.

“Is it done?” asks Jarkko.

“Your master is close to the end now,” she gasps. Even from here she can see the bloody mess inside the tower. As she cries out at the next stabbing wave of pain, a man comes hurrying from the manor with a sack over his back and the look of a frightened mouse. One of the guards starts towards him and then the other two. He runs but they catch him and put a sword through him. Food and stolen pots and candlesticks spill out of his sack across the yard. Another servant freezes on the open threshold of the house as the guards look up from what they’ve done. They give chase again and all run inside. Sola can’t see what happens but she hears a muffled shout and then a scream. She turns to Jarkko. “Please go!” Her insides feel as though they’re ripping themselves apart. “Please.”

Jarkko shakes his head but Sola cannot bear this pain much longer. She ducks into the darkness of a servant’s shack where the air carries a faint whiff of Goso bark. The elixir she’s taken with each of the old man’s sins has held them fast. In this way his sins remain whole, not yet dissolved, not yet hers, but there are simply too many to keep inside her; her belly is swollen and stretched and the pain is insufferable. She looks at Jarkko, here to stop her from exactly what she must now do. She’d meant to wait, to do this where he wouldn’t see but that choice is lost to her now. She must take the old man’s sins and make them hers or she must spit them out; and so in the gloom she takes a second gourd from her belt and gulps it down and then vomits up stones and sand into her stolen bucket, all of them, expunging them until every last one is out. The piece of blanket comes last. It sticks in her throat, almost choking her as she retches until finally she pulls it free. The relief is indescribable.

Jarkko stands and watches. She doesn’t see the expressions change on his face as she throws up the old man’s sins but when she’s done she looks up at him. Will he kill her now? At the very least he should make her eat them again. But he does nothing and only looks. Sola spits and washes out her mouth and carries the bucket outside into the sunlight and slumps with relief. She’s vomited blood but only a little. She hasn’t left it too late. She takes a mouthful of filthy water and spits it out again and cleans the stones and tips them into a leather bag and then counts them, one by one against the record in her little book. Then she waits for Jarkko. She can’t run from a man like that and she can’t fight him. She steels herself. He’ll tell her she must eat them. She’ll refuse. Maybe he’ll dare to kill her then, maybe not, but there’s certainly a great deal of other unpleasantness he can give.

The Graved comes and squats beside her. “You meant to do this all along?” he asks quietly. There’s an unexpected sadness to him, that’s all: nothing that speaks of anger or violence.

Sola nods.

The three guards return from inside the house. They have sacks of their own this time. They glance at Jarkko and hurry away and don’t look back.

“Now what?” Sola asks. Perhaps he has the strength to force the old man’s sins back down her throat. If he tries then she’ll bite his fingers to the bone. But she remembers him too, in the night, with the drawn blade in his hand, looking at her with such pain.

Jarkko gets to his feet. “Now nothing.” He walks away.

Sola sits a while longer, waiting, but Jarkko only walks to a corner of the yard and stands, deliberately turning his back to her. When he doesn’t return, Sola slowly gets up. She takes her bag of the old man’s sins and walks inside his house and returns to his room. The Magus is abandoned, shaking in uncontrollable spasms. Behind closed lids his eyes roll. It seems he’s already crossed the veil, that he doesn’t see this world any more, but he’s not quite dead, not yet. Sola leans over him and touches his face.

“One of those bastards you meant to drown wasn’t a boy.” There are no servants clustered around, no weeping women. They’ve all left him. She takes her bag and empties the stones and sand into the old man’s unseeing lap. “Here are your sins. Will someone come to save you? Will someone love you into Heaven?”

No one comes. The manor is empty, soundless but for the songs of birds in the warm summer sky. Sola stares at the dying old man. She feels a fire inside her, a great warmth or release. Slowly she passes a hand over her own face, gags for a moment and retches and spits out a black stone like an apple pip. She throws it down among the rest. The sin of vengeance.

“Burn in Hell you bastard!”

She stays to watch him die. After a time the Magus falls still, his skin fading to the translucent pallor of death. His jaw starts to work, wriggling up and down, and beneath closed skin his eyes pulse and squirm. Their lids sink into his face and a swarm of black beetles bursts from inside him, from his eyes and mouth and ears. They spread across the blanket, over the side of the bed and across the floor, scurrying away into shadows and gloom. Sola watches for a moment and then walks to the door. She closes it behind her and leaves.

Outside in the yard, Jarkko is still there. “I’ll walk you down to Elsporth,” he says.

The Sin Eater (21/7/2014)

The Sin Eater

Servants usher Sola into a sterile stone antechamber. They whisper to one and other, solemn and funereal. Sola watches their dead eyes, their pallid skin, the expressionless rictus of their faces. She’s seen it all before, the whole spectrum of it, the wild wailing abandon that comes from watching a cherished life crushed to an unexpected end, the tearful smiling farewells to a much-loved elder, the tomb-like masks of servants waiting for relief from a master who won’t be missed. The death she’s come to witness today has a savagery in the air behind its careful silence. Fear and envy and outright hatred boil together, their parts changing every hour. It glides over her like water over feathers.

The antechamber walls are bare, stripped. Faint outlines show where paintings and tapestries once hung. There are three doorways – the one she stands in; the next a battered wooden thing that once had a hanging in front of it; the last much grander, although its gilt has faded and the dark hardwood shows its age. An elderly servant with an etched face sweeps his arm with reverential ceremony, guiding Sola forward. All their motions are careful as if they’re afraid to disturb the air, as if that might hasten their tyrant master’s demise. Sola mimics their delicacy. Some of their hostility is for her. Sin-eaters are strange men and even stranger women, feared and revered, blessed and cursed, holy and damned both at once. Some say they are half demon. Others that the blood that flows in their veins has been touched by the essence of angels. The suppressed anger, though? They hide it badly. The man she’s here to save truly deserves to go to Hell.

Inside the bedroom the old man they all hate lies sleepy-eyed in bed. Sola looks him over. She’s never seen this man before but she’s heard of him, oh yes. Even knows his true name though he never uses it any more. She decides she will call him Magus, a reflection of the darkness at his core. She’ll call him that and come to no harm for it, just as she might call a king a fool to his face and feel no fear of the gallows. Sin-eaters stand outside judgement. Some have been murderers, rapists, plunderers and pirates, the very worst kinds of men and women – but they are always saints, outside any law but God’s, for to kill a sin-eater is to take on her sins.

Sola gathers herself and sits beside the old man’s bed ready to guide him to Heaven. The Magus has a blanket pulled up around his armpits; it was beautiful once, made by the weavers of Belasas a thousand miles away. A blanket like that costs more than a pair of good racing horses, probably more than everything Sola has ever owned, but this one before her is threadbare and stained. The old man’s head and shoulders are propped up by a wedge of fat goose-down pillows. His arms lie over the top, limp and pressed against his sides. His face is speckled with the marks of age, his hair thinning and white. He’s already ancient. Time, always fickle, has turned its back on him.

Two other men wait on him. A thug-faced soldier in a brigandine coat with a rapier on one hip and a pistol on the other, and an oily-skinned snake disguised as a man, preening his thinning hair as he stands in his fine red silk robes. The oily man speaks. “I am Eserleri, chancellor of Elsporth. If you have needs or grievances, please bring them to me at once.” He bows with an obsequious smile and an expansive flourish.

Sola nods. She looks from him to the second man, the soldier. He’s feigning boredom and a dull lack of interest but she sees right through him. Underneath is something else. His eyes don’t leave her and his gaze is hard and cold. If he had the freedom, she thinks, he would cut her down right here.

“Jarkko will keep you honest.” Eserleri keeps his smile, bright and wide with malice. “Jarkko is a Graved.” When the snake says that the solider will keep her honest, he means the Graved will never let her out of his sight outside this room until the Magus is dead. He’s there to see she doesn’t secretly vomit up the sins she’ll eat and bury them. No one knows what happens then. Is the sin-eater cheating God and Heaven? Do the sins simply return whence they came? Do they vanish, lost from the great divine account? Where do these orphan sins belong and who will be judged for them? Only God knows the answer and so the Magus is taking no chances.

Eserleri bows and withdraws, slowly and with reverence. The Graved Jarkko follows with a swagger that says he doesn’t give much of a shit one way or the other about any of this and doesn’t want to be here. The Magus hisses and waves his skeletal hand and then, at last, looks at Sola. His eyes crawl all over her. There’s meaning in that look. “So Jarkko finds me a girl,” he says in disgust. “Their bile is always there, spewed out behind my back though they’d never dare show it to my face, not one of them. A girl.” He spits out the word.

“I am a sin-eater, Magus,” answers Sola.

“And I’m dying.” He glares at her as if his very look might flay the skin off her face and so make her more to his liking. She holds his look, calm and steady. She’s seen a lot of old men on their deathbeds and a lot of old women too. Some shower her with words of gratitude. Others hate her.

“Death comes to everyone,” she says. “Kings and peasants, all must pass away.”

She bows her head and tries to hold a sombre moment and dangle it between but the Magus only frowns and scrapes his throat and spits a smear of phlegm onto his once-priceless blanket. “That supposed to cheer me is it? My death doesn’t come to just anyone.” He taps a bony finger to his skull. “There’s a beetle in my head, girl, and it’s eating me.” He bares his teeth and hisses again. When Sola doesn’t flinch, he cocks his head. “Did you hear? I said there’s a beetle eating the inside of my head!”

“The Lord Ambassador who preceded you,” Sola says quietly. “I heard he died the same way.”

“Everyone knows that story.” The Magus coughs a little laugh. “Does it make your stomach crawl, girl? I can feel her scuttling around in here.” He taps his skull again. There’s a twisted affection in his words. She’s seen it before, once from a farmer gored by his own bull and once from a duellist beaten and killed by a blade that dazzled brighter. The beetle in the old man’s head has the better of him. It has his respect.

“How long do you have?” asks Sola softly.

“She’s eating away at me now but she won’t kill me on her own. When she’s had her fill she’ll lay her eggs and die. Thousands of them. When I stop feeling her little taps and knocks scraping around in there then I have hours before they hatch. That’s when it happens. Do you have that long, girl?”

He calls her girl as though it matters, as though she should feel somehow lessened by it. Like the hostility of the servants, it slides away like water over oil. The old man will be dead soon and so she sets his unkindness as a railing against that end. “I have as long as you require, Magus.” She might ask whether the old man thinks he’ll have long enough for all the sins he’ll be spewing out of him but that doesn’t strike her as a very holy question, and for now she has a mask to wear. “Have you ever witnessed a sin-eating, Magus?”

“Of course not.”

“It’s best to start with some small thing so you understand what happens.” She bows her head. A sin-eating is a private thing, like confession, though she can’t imagine the Magus paying any heed if that ever got in the way of what he wanted.

“I’ve been unkind to my horse.” The old man laughs and then stops abruptly as Sola passes a hand over him. His eyes fly open; he jerks upright and coughs and retches and at last spits out a stone. He stares at it in wonder, the size of a holly berry and as black as the hollow eye of night. “God in Heaven, girl, I thought you’d killed me,”

Sola picks up the stone, slick with the old man’s spittle. She holds it between them. “This is the sin of being unkind to your horse,” she says, quiet and gentle as a whisper of autumn. “It is taken from you.” She places the stone in a silver bowl and rinses it with water, then dries it with a small square of white silk. She puts it in her mouth and swallows it down with a swill of herbal elixir made with ingredients bought from the Elsporth apothecary the day before. “I have eaten your sin, Magus. You may choose what you will give to me and what you will carry with you to bare before God. I will eat whatever you offer.” She meets his gaze again, level, ice for ice. “It is, as I say, best to start with something small.”

“Oh you can have all of it, girly, every one of them. The devil might want me but I mean to disappoint him.”

Sola nods. She takes out a book and flicks to an empty page. As the Magus speaks, she begins to write.

The Lord Ambassador – the Magus as Sola calls him – lives in a fort atop a thrusting rocky outcrop called Biter’s Drop. Jarkko, who is quietly curious about the name, folds his arms across his chest and pretends to doze. A sin-eating is a private business but when the sin-eater leaves the old man’s side, Jarkko will never let her out of his sight until one of them dies.

In his mind’s eye he eyes up the innards of the little fortress. An old lookout tower rises from one corner, wrapped in a sheath of vines that reach almost to the top in their effort to drag it down. Elsewhere a collection of rickety wooden sheds press up against the walls: a kitchen, some hanging shacks and storehouses and a lean-to that passes as shelter for both servants and travellers. A tight road winds reluctantly from a shabby gatehouse down to the river below, too steep and twisting for a cart or a wagon. At the end of it, Biter’s Drop overlooks the Charred river and the little market town of Elsporth and then a thick wall of forest where the Graved live.

Elsporth still bears the scars from the last time the Graved came. Six years he’s been here. Six years since he came across the Charred with his kinsmen and gave them away. He’s waited a long time since then and he still doesn’t know how Biter’s Drop took its name, who bit whom and who fell or was pushed. Someone, once long ago. Probably he’ll never know.

He thinks of his prostitute who waits in Elsporth. Thyronis is slender and often mistaken for a woman. Occasionally he dresses as one too. Jarkko, on the other hand, is a brute. With his hair hacked short and his scarred face, most people see a Graved and nothing else. He carries a double-headed axe across his back which is how it came to be that he once rescued Thyronis from a gang of sodomites who didn’t seem to care much what he was under his dress. Or perhaps he needed rescuing because he was a thief. He still is. Right now, Jarkko imagines Thyronis looking up at the keep and its tower, his head full of thieving thoughts.

A servant comes through carrying a pitcher of milk. He goes into the bed-chamber and quickly comes out again.

“I’m hungry,” says Jarkko, but the servant only laughs and goes through the low wooden door. A curtain hangs half torn from the roof beyond. There’s the unmistakable sound of piss into a pot. The servant brings with him the stale smells of smoke and candle fat that remind Jarkko of the flop-house in Elsporth: a room with a hearth that hasn’t seen a fire for months, a table that wobbles, a handful of stools that aren’t quite straight and a single chair. He imagines Thyronis pacing back and forth, looking here and there, searching all the nooks and crannies for lost pennies and those cheap bone-carved loops and needles that the people here like to wear in their hair. When he closes his eyes he imagines hearing little yelps of delight whenever Thyronis finds one.

The Lord Ambassador would have Thyronis executed by shoving a red-hot iron spike up his arse if he knew of Thyronis’s tastes. It’s a dull, distant tyranny. Six years he’s been here. He still doesn’t know how Biter’s Drop took its name but he knows by now that the Lord Ambassador deserves eternal damnation more than any man he’s ever known. And now he must see to it that this sin-eater guides the old man to Heaven.

Sola is writing in her book again, tiny and precious and scribbled in code. Every sin she eats must be written down to be spat out again one day lest she be cast into Hell, fodder for greedy Lucifer. It’s not a life for everyone. At least priests with their confessions don’t damn themselves by what they do.

She looks up. They’re done now with how the Magus treats his servants no better than his horses, how he had one whipped to death one day for no better reason than he felt like it and wanted to set an example. There’s the matter of the war, half a decade back now when the Graved came across in boats and sacked Elsporth and the Lord Ambassador shut his gates good and tight and did nothing until the raiders tired of their sport. He let them have their fill. It was the start of an invasion, he claims, but he gave them Elsporth and set them to fighting among themselves and the grand war that might have been came instead to nothing. Eventually they settle on the sin of ‘acting in his own interest over that of the common folk who looked to him for protection.’ The Magus is reluctant but spits it anyway. Better safe than sorry. The stone he coughs up is the size of a small plum. It takes some swallowing.

“What about greed?” Sola suggests. Greed, lust, gluttony, sloth, wrath, envy and pride, every sin-eater learns them. Abandoning his people to die under sword and fire might be called sloth, though Sola prefers the older term of acedia: an abandonment of duty, a neglect of one’s purpose and talent.

“Greed?” the Magus laughs. “You’ve heard the stories then?”

Hidden under her cowl, Sola bites her lip, forcing herself to be still and quiet. A good sin-eater coaxes the sins out of the man she means to save, one by one until all are gone and nothing more. Judgement is left for God.

When all the Magus gets is silence, he adds a little sourness of his own. “Very well. Yes, I murdered the Lord Ambassador Yardis, my predecessor. I murdered him for his wealth. There. Happy?” This is a rumour so widely spoken as to be a part of local history, a thing taken as fact. It’s why Sola has come here, to hear this. But still, behind her mask of bland acquiescence, the admission jolts her more than she’d expected. The horror isn’t so much that he did it. It’s how.

“Was it simple avarice, Magus?”

“What’s it to you, girl? I did what I did. The reasons don’t matter.”

Sola bows her head, hiding her expression. It’s hard enough to control her voice, never mind her face as well. “I would send you to God with your soul cleansed, Magus. Speak as much or as little as you wish. The saints will judge you for that which you still carry when you stand at Heaven’s gates before them. It’s for you to choose what you leave behind.”

The Magus shifts, uncomfortable but caught. As much as anything this is why he sent Jarkko to find him a sin-eater. Mere confession never feels enough. “Look about you, girl. What do you see? A little rural province too far from the Holy Court to attract attention. A thriving port with more boats coming in than you might think. Out there in the forests on the other side are the Graved, too busy fighting each other to offer much of a threat. And a Lord Ambassador clearly taking half of what should be sent to the Holy Father for himself? I came to Elsporth twenty years ago as a listener, as the eyes and ears for His court, and I saw the same. I told Lord Ambassador Yardis that he was a thief. I told him I’d say nothing if he gave me a piece of what he was keeping . . .”

Sola passes a hand over the Magus, who, startled, coughs up the obsidian sin of blackmail. She washes it in her silver bowl, dries it, swallows it with a mouthful of elixir and makes a note in her book. The Magus has coughed enough wickedness now that he barely breaks his stride. “Is that the greed you wanted?” He sinks back into his bed and stares up at the ceiling. He has a strange look in his eye, the first time Sola has seen any real emotion through all the litany of his life. A remembering. A regret, is it? A tightening of the lips betrays an old anger. “He cast me out,” says the Magus. “So after I returned I sent him a gift. Sugared dates from the homeland I left half a century ago, laced with the eggs of my little beetles. When he ate them they hatched into larvae. The larvae burrowed into the flesh of his gut and crawled through his body into his head. Once they were there they started eating. I’m told it took him an hour to die; that after he fell he was still for a while and then his face began to twitch and his head jerked and a swarm of beetles erupted from every orifice, from his nose and mouth and ears and eyes. When they cut him open his skull was empty. Scoured clean.” The same story that everyone knows for a hundred miles. Beetles like the one the old man has inside him now. Sola bites on the irony as she passes her hand over the Magus who spits out the sins of greed and murder. She cleans and swallows them, drinks and writes them in her book but the Magus is shaking his head. “Seven others died, sin-eater. His taster, who didn’t die quick enough to save the rest of them. His wife and his brother, two children and two of his guests.”

The Magus coughs seven more times. Sola swallows the seven black stones he spits out.

“After the Graved razed Elsporth I sent a few more gifts to their king and their barons.” The old man winces. “And there’s the sin of vengeance for you, girl, and wrath as well.” He stops and stares at Sola long and hard and then smiles a bitter smile. “All the wealth you think I have? Gone. There’s nothing, sin-eater. All I have are my beetles.” He fluffs his goose-down pillows. “I bought enough to kill every Graved between the river and the sea. I sent my presents to the court of every baron I could name. All dressed up as gifts from one to another and certainly not from the Lord Ambassador of Elsporth. I don’t know how many of them were taken. A lot. Ask Jarkko if you like. I’ve noticed they’ve been busy killing each other these last few years. Very little trouble to me at all. What sin is that? I was protecting my people. Doing my duty. I have no idea how many of them died. Is it a sin at all?”

Sola passes a hand over the Magus. “For all the Graved.” The old man coughs and spits out a gobbet of wet black sand. Hundreds of tiny grains, perhaps one for each man dead. They both look at the sand staining the once-priceless blanket, then Sola scrapes up as much as she can and swallows it. She fastidiously licks her fingers. Grains are left stuck in the soft weave. More cling to the Magus’s lips and inside his mouth. She passes him a pitcher of milk and a cup. “Get every grain and spit it out. Every one you miss you’ll carry with you to the gates of Heaven.” While the Magus does this she gently pulls at the blanket. “How much time do you have?”

“I still feel her crawling around in there. She hasn’t laid her eggs, not yet.” The Magus looks at her. “Come again in the morning.”

“Is it quick, this death of yours?”

“Quick enough. Once her eggs hatch they’re voracious little things.”

“You know the price for a sin-eating, Magus?”

“You want my treasure? I told you I don’t have any.”

“It’s no use to you in Heaven, nor in Hell.”

“What remains is yours when you’re done if you want it.” He laughs. “I’m sure we can find you something.”

Sola takes the blanket and carefully folds it, making sure that none of the grains of black sand fall out. She carries it from the Magus’s bed, through the antechamber, down the stone stairs into the hall below and to the tiny room she’s been given while she stays. The servants leave her alone and keep out of her way. The Magus’s watcher, Jarkko, falls in behind her. He moves too quickly, giving away the anxious burning in his thoughts. Now and then he simply stares as if looking deep into the past or perhaps the future. Each time, Sola sees the transformation of his face, the ugly twist of hate and murder that lights with bloody fire in his eye.

“Tomorrow,” she says as she watches him. “It’ll all be done tomorrow.”

Jarkko grunts and follows her into her room. Sola lights a lamp and prays and then with painstaking care sucks out every last grain of sand from the blanket. When she’s done she cuts out the piece now stained wet with her own saliva and eats it. Best to be sure. She drinks milk to force it down and then takes another draft of her elixir. It’s unusual for a sin-eating to take so long or for there to be so much. All the old man’s sins make a weight in her stomach. She’ll have cramps in the morning, bad ones. She lies for a while, staring at the ceiling while Jarkko sits silent in the corner, watching. A sin-eater must grow used to sleeping like this, with eyes looking over her. Eventually she goes to sleep.

Jarkko sits, sleepless and restless. In the dead of night he hears shouts in the yard and screams and a clash of arms. The Magus isn’t yet dead and already his men are fighting over the spoils. It calls to him, urging him to make an end to this.

Sin-eaters carry the secrets of the men they save. Some travel with bodyguards to protect them from devils and plunderers who would steal them. Not this one. Silently Jarkko draws a knife from the sheath at his belt, ready to kill this sin-eater who will save his master. But he stays his hand. This woman has eaten half the old man’s sins. Slit her throat and they become his. He doesn’t know how he could live with that.

Sola hears the commotion too, the screams and the shouts, a quiet for a while and then a hue and cry of alarm and more fighting. She doesn’t move. She watches Jarkko through half-closed eyes and sees him draw out the knife and pause and slowly slide it back. She sees the anguish in his face and wonders what it can mean.

“You can go if you want,” she murmurs but he shakes his head. She lies back and listens, in the quiet moments, to the rhythmic tread of boots back and forth on the wooden boards outside her door.

She’s asleep again long before the commotion subsides but before dawn she wakes again with a gasp, stricken by crippling pain. Stomach cramps. Vicious ones, every bit as bad as she feared. The sooner this is done the better. The manor has a different feel to it today. There’s an emptiness as she returns to the Magus and Jarkko tramps wordlessly behind her, a sense of the forsaken. She doesn’t see a single servant as she walks to the Magus’s bed. The smells are wrong, the air adrift with the scents of unlit fires and cold empty bread-ovens. Everything is absence. The room where the Magus lies is near-lifeless too. A plate sits beside his bed and a half-empty pitcher of milk. The Magus regards her. His eyes glitter with hate.

“You did this.”

Sola gestures calmly to Jarkko. “Your watcher never left my side.”

The Magus stares on until the venom transforms to something else, something more bitter still. “I had a wife for a while. She bore me three heirs. I was cruel to them all. I beat them. She despised me. I knew she had a lover and knew she planned to run and I knew the Graved were coming. I sent her down into Elsporth the morning before the Graved crossed the river. I didn’t mean for her to take my sons. I didn’t know until it was too late. They were all murdered amid the slaughter the Graved wrought. I brought that down on them. There. The heart of my vengeance. Take it.”

Sola passes her hand over the Magus but nothing comes. She shakes her head. “Grief is not a sin, Magus. I cannot take it.”

“My servants are looting my carcass before the light fades from my eyes.”

“At the gates of Heaven, all counts for naught but that which you carry on your soul.”

“Lift your hood, sin-eater. Let me see you.”

Sola hesitates. Her cowl comforts her and keeps her features half-hidden in shadow and hides her emotion. But the Magus is looking hard and won’t be moved and so she draws it back.

“You have a resemblance to Yardis, you know.”

She imagines her eyes all a-glitter. She lets out a grimace of pain, screws up her face and clamps a hand to her stomach. “Forgive me, Magus. The cramps have the better of me for a moment. I . . .”

“He had four bastard boys from three women among his servants. I found the women and hanged them. The bastards were drowned in the river.”

When the cramps ease, Sola passes her hand over the Magus seven times, one for each murdered woman and one for each child. The Magus spits six black stones like grapes onto his blanket, another gem from Belasas but even older than the first. The seventh stone is smaller. The two of them stare at it.

“Why aren’t they the same?” asks the Magus.