Benjamin Cross's Blog

August 29, 2020

Colony: the story behind the book... Part 2, Finding an Agent

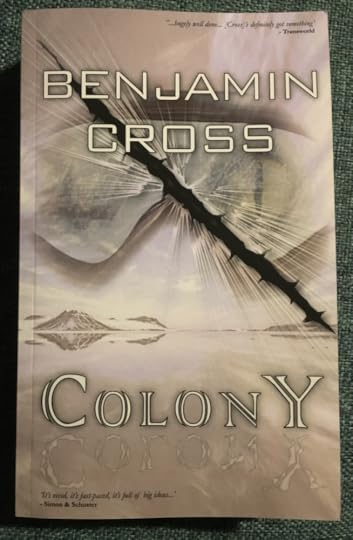

Welcome along. Before I start this blog, I just want to say a huge thank you to all of you who have read Colony so far, and for the very generous praise and reviews that it's received from so many of you. Those of you who haven't read it yet (but would like to), the trade publication date is still January 2021; with any luck that same month will mark the start of a much better year for all of us!

So let's talk about agents. (Not secret. Literary. Trust me, they're much tougher.)

One of the many many realities to confront a new author is that the chances of an unsolicited (un-requested / speculative) submission being accepted or even considered for publication by a commercial publishing house are remote. And even assuming an unsolicited novel was picked up, the chances that that newbie author would have any idea about publishing contracts, royalties, rights and all the other commercial publishing aspects that can make or break a career are also remote.

It's not the case that publishers would want to exploit new authors, or otherwise take advantage. But the reality is that once a book is written and offered up for publication, it ceases to be a purely creative work and becomes a commercial prospect. One of the biggest reality checks I got was discovering that the length of your average novel isn't guided by the story, but by commercial factors such as: what length a particular genre's readership expects, per-page printing costs, and even the number of copies that need to fit into a particular size of box for distribution.

So while their output may be creative works, publishing houses are businesses first and foremost, and they are very much driven by commercial considerations, targets, turnover and, yes, profit. That's no bad thing. It's how business works, and how a lot of great books get published. But combined with a newbie author's emotional investment in their work and lack of commercial savvy, they are at least at a disadvantage when it comes to contractual negotiations and understanding their rights and responsibilities.

Enter the literary agent.

If you're not familiar with what a literary agent is or does, then they are basically a publishing industry expert contracted to represent authors and sell their work to publishing houses. They are effectively the 'middle men' of the publishing world. The value they add for authors derives from their knowledge of what publishers are looking for and when, and in particular their close relationship with publishing house editors. The reality is that editors are far more likely to consider manuscripts received from credible literary agents than speculative, unsolicited manuscripts submitted direct by unpublished authors. And for good reason.

From a publisher's perspective, literary agents fulfill something similar to the role of scouts in professional sport; they identify the top potential from an otherwise colossal and unwieldy pool of wannabes. Publishers can therefore have confidence that the manuscripts submitted to them by literary agents are going to be of a particular standard, commercially viable and worth expending the time and resources necessary to read and consider.

That is the reason literary agents have such notoriously high standards and are so difficult for new authors to 'land'. Publishers are their bread and butter, and their value to publishers is based upon their objective rigor. It is a perfect example of commercial symbiosis.

Agents are also much better versed in the minutiae of publishing contracts, terms and conditions. They are much more likely to be able to negotiate the best possible deal(s) on behalf of the authors they represent, and guide them through the minefield that is the publishing industry.

In return, agents take a % of their authors' earnings, typically between 12% and 15%. In my view, this is a sound investment. 88% of nothing is nothing, while 88% of £1000 is £880. And an agent's commission is only due if/once they actually sell an author's novel. Prior to that, they will typically add a huge amount of value. They will read an author's manuscript multiple times, provide expert critique and help them batter it into great shape. They will then use their contacts to pitch the novel and pursue responses. A good agent will also provide emotional support, coaching and even friendship. And all the time they are working on faith (not commission), driven by an educated belief that your novel is of a good enough standard to stand shoulder to shoulder with established authors on high-street shelves.

Okay, so agents are a big deal. So how exactly do you get one?

In short, you have to pitch your novel and yourself. This is another steep learning-curve, and more than ever as a newbie you need to develop a very thick hide very quickly. Few authors, no matter how successful they go on to become, will not experience the dreaded 'R-word'. Rejection. Let me tell you, each rejection hurts like hell. It's nothing personal of course; it's commercially-driven. But at the same time it is virtually impossible not to take it 100% personally when you are on the receiving end. It can't be anything else when you've worked so hard and dreamed so long.

Colony was rejected by half a dozen agencies at least before I finally received the phone-call from my agent to say that she loved the manuscript and, subject to a few revisions, would be delighted to represent me. The worst to receive are 'form' rejections, which basically consist of a standardised cut n' paste response, into which the name of the latest unsuccessful writer is inserted before the secretary hits send. These come with a particular sting because they are so impersonal; in effect they convey the following message: 'not only did we not enjoy your submission, but we found it so unremarkable that we are not inclined to even provide you with a personalised response. Now please do us all a favour and piss off.'

Of course the real reason is that they simply cannot respond individually on every submission they receive, due to the sheer volume. My agency, for example, receives somewhere in the region of 100-200 submissions per week and takes on between 10 and 20 new authors per year. Providing individual responses to each of those who are unsuccessful would be a full-time job in and of itself. That said, agents do send personalised rejections on occasion. This is most commonly when they've been impressed by a submission and either want to provide some words of encouragement to a writer they consider promising or want to justify why they haven't taken a promising novel on. I was lucky enough to receive a couple of these for Colony and they meant a lot. One agent in particular (one who had requested a full) communicated with me extensively and gave me some great advice despite ultimately rejecting the submission.

Every agency has its own bespoke submission requirements, but in general they all boil down to some combination of the following: i) a cover letter setting out your experience and biography, what your novel is about and how it would place within the market; ii) a synopsis outlining the development of your novel; and iii) the first few chapters of the novel itself. That's stage one. It gives the prospective agent enough information about you and your novel to decide whether you are a time-waster. If they decide you're not, and they enjoy/see potential in what they read, they will then request the full manuscript ('a full').

Having a full requested is a triumph in and of itself. If you consider how long it takes you to read a novel on average, then the agent is interested enough to commit that length of time to reading what you've written. If not for quiet confidence, this is at least a time to give yourself a well-deserved pat on the back. Maybe even to dream...

If you enjoyed this blog, then join me again for Part 3, where I'll be talking about the publication process and what goes on behind the scenes. Oh, and I'll try not to leave it 2 months between blogs this time! Take care til then.

May 29, 2020

Colony: the story behind the book... Part 1

Those of you that follow me on Facebook or Twitter will know that there's been a development with Colony recently. It's been picked up by a trade publisher, who will undertake a new round of edits, re-typeset the text and re-design the cover. They will also market the book both online and on the high street. It's a strange and unexpected development with this book that I've been nurturing for nearly a decade now.

For perspective, when I started writing Colony I was still in my 20s. I was in the early stages of my career in heritage, unmarried, childless, with few grey hairs and weighing in at under twelve stone. Fast forward to today. I'm 40 next year. I'm an Associate Director and expert witness on heritage matters at Public Inquiries, 7 years married, two kids (6 and 4), a home-owner with easily as many grey hairs as brown, and pushing 14 stone. It's fair to say times have changed.

Mentally, a first novel is always going to be an uphill struggle because you have no idea whether i) you'll be able to finish it, ii) it'll be any good, or iii) how it'll be received by others. Basically, you spend the entire process wondering whether at best you're wasting your time or at worst you're completely deluded. It's what they describe in the industry as 'writing into a blackhole'. It's massively uncomfortable, and it's one reason why finishing a book is so hard to do.

Like many aspiring writers with a day job, I wrote much of Colony late at night after work, as well as on weekends. My 'office' was split 50/50 between the couch and coffee shops. It took me four years to write, an almost obsessive preoccupation with putting words on page and a ferocious contempt for the blackhole.

There were times when I wrote non-stop, only breaking to eat and sleep and pretty much side-lining all other aspects of my life. Then there were times when I wrote nothing for months, either because other life events had taken over or I'd simply succumbed to the uncertainty and other pressures and just given up for a time.

More rarely, there were times when I did manage to strike a balance, or at least make peace with the lack of balance and settle into a comfortable arrhythmia.

Of course, all writers write differently. But there are perhaps three key choices that face us all from the outset:

To plot or not to plot?

Whether to plot everything - storyline, structure, characters etc. - in detail before starting on the prose, or to start with a broader concept in mind and let the story unfold on the page.

I started off trying to plot the novel. But for me this seemed to sap all of the joy out of the writing itself. Don't get me wrong, I'm not somebody who sees writing as a pure form of art, self-expressive at the expense of all else. The process is a creative one. But, as with most things, there are also rules and realities that guide it for the better and that need to be balanced against the art.

One thing I do strongly believe, however, is that you can tell when a writer is enjoying themselves, or if they are on commercial autopilot. And I know which of those I prefer to read. So, when I eventually got cracking with Colony, I was one of those who starts with a broad outline in mind; I knew how it would begin, who the characters would be, what major events would take place, and how it would end. But the rest was very much TBC.

To edit or not to edit (until drafted)?

Whether to perfect each section before moving on to the next, or to draft the entire novel through in a continuous fashion before editing back through from the start.

Being a perfectionist (a.k.a. anal), I found the idea of leaving a trail of drafted chapters in my wake, with a view to editing them all at some future point unknown, a pretty horrifying prospect. Interestingly, I did take that route with novel #2 and I'm now much more sold on it. But with Colony, I edited each chapter to within an inch of its life before moving on to the next. This is part of the reason why it took so long for me to finish.... that, and having kids.

To reveal or conceal?

Whether to allow others to review and comment on the story as it emerges, or to keep the whole thing under strict lock and key until fully complete.

From my experience, this is a crucial choice. I made the decision early on that either I would die, finish the book or it would never see the light of day. I didn't let anybody - not even my wife - read a single word of Colony before it was finished. It was difficult for sure. But it was a smart move.

There is a world of difference between a work in progress (WIP) and the final product itself. Presentation aside, a lot of this is down to psychology. When you finalise something, e.g. a report at work, you've taken the decision that it's as good as it can be, given the time and resources available. So you draw a line under it and open it up to critique. When the comments roll in, both they and you as recipient are informed; whoever has edited your report has seen the introduction, discussion and conclusions. The whole shebang. You've invited their critique at a time when you can use it to produce a final product.

By contrast, when a writer invites somebody to comment on the introduction only, or on an unfinished passage from the middle of their story, they are inviting comment on something that is both half-baked and lacking in context. It may be years before the rest of the book is drafted, by which time the passage in question may have been altered or cut entirely, or the critique otherwise rendered useless. Arguably worse, the critique may shape the novel in a way that was never intended.

For various reasons, I invited comment on the first 30k words of my current WIP (novel #3), and it was a mistake. One of the comments was on the structure, which I duly re-configured in response. It ruined the story. Why? Because neither the well-meaning critic nor myself fully understood where the novel was heading. And when it finally reached its destination, three things were clear: the suggested re-structure was wrong, the critic would never have made it and I would never have accepted it had the novel been complete at point of critique. But that's for another blog.

Returning to Colony, with the manuscript finally drafted I was next faced with the choice that confronts all new authors: what to do next. And realistically, this boils down to two choices. Whether to cut out the middle man and go direct to publishers, or to try and land that most illusive of all things: a literary agent. For me personally it was a no-brainer, and I'll tell you why in Part 2.

April 25, 2020

Excavations @ Cwm Dwfn House: Part 2

My last blog on the impromptu excavations in my backyard was focused on the pottery that's been turning up. But I mentioned that a few non-pottery items had revealed themselves as well, mainly glass and metal. Some of these are pretty cool, so I figured I'd share them.

After the pot, the next most common things I'm finding are shards of glass, mainly from bottles and storage jars. I'm only keeping a small number of these as there are tonnes of them and most are quite recent. So here's just a selection of the more interesting ones.

Top left is a bottle stopper, and it's probably the nicest piece that's turned up. The others on the top row are: the base of a small vessel, the base of a shot glass (with another base shard below), and part of a bottle top. Bottom right is part of a jar rim, while the others are body shards. Of note, the translucent shard in the middle of the bottom row is very fine, with a red-painted edge, and may have been from a display piece. All of these probably date to the 19th / early-20th Century.

As well as the vessel shards, there are also a couple of possible costume items, including what I think is a broken button (this looks black but it's actually purple) and a blue necklace bead, which I think may be faience; the full necklace must have been a beautiful thing.

A couple of the metalwork items also relate to costume, being a (brass?) buckle and an iron hobnail. The buckle is quite large, and may have formed part of a horse harness, rather than a belt; if the latter then whoever wore it must have been (to use the technical terminology) a big bugger. The hobnail would have fastened the sole of a shoe.

In terms of the other metalwork, the items are mainly domestic in nature, as you'd expect. Two of them once belonged to fireside companion sets, including a little brass coal shovel and a pair of quite elaborate Iron and copper alloy tongs.

The below is probably a brass pommel, so the decorative part of a handle. I can't be sure, but one possibility is that it was once part of another fire iron implement, e.g. a poker. Guess why they threw it away??

I've no idea what the below is, but it looks like decorative edging for something. Got a bit more research to do on this one.

Other than domestic items, a number of different items related to... wait for it.... drum roll... farming have turned up more generally across the farm. To these, I can now add the below, which (I think) may be a bull nose-ring.

And finally for now, I'm finding the sorts of things that I've just got no idea about. No doubt there is an obvious, and probably uninspiring, explanation for the below. As it stands though, to me they remain chalk-sized cylinders with a dot-dash pattern along their sides. I'm not even sure what they're made of; might be stone, some kind of resin, some kind of hard-fired ceramic, or none of the above. I've no idea. Answers on a postcard...

So I've dug a huge amount of soil over the last few days and found a lot of other things that I haven't talked about in this or the previous blog. I'm going to wait until I've wrapped up the dig now to give you guys and gals a third and final update.

Take care until then.

April 21, 2020

Excavations @ Cwm Dwfn House: Part 1

It started off innocently enough (doesn't it always). The garden's on a slope and I wanted to level part of it off to create a seating area. Sounds simple, right? It is! Unless of course you've got a thing for ancient trash...

So, I stripped the turf off the area in question and slung it on a heap. Even with down-time to nurse my nettle stings and red ant bites, I was steaming ahead with it. I was making such good time in fact that I decided to have me a little break. And that's when it all changed.

No sooner had my ass touched the grass than I spotted something sticking up out of the subsoil. 'Ah whatever,' I told myself. I'm not on the clock here. Who cares even. But who was I kidding. I reached out, plucked it from the soil and brushed the dirt away. It was a shard of 16th-/17th- century pot; for context, Elizabeth I was on the throne and Shakespeare was busy scribbling away during the second half of the 16th, while the Civil War (Charles v Cromwell) took place during the mid-17th, that sort of era.

Pottery of 'post-medieval' date (as it's referred to by my archaeological brothers and sisters) is not especially uncommon. It was during this period that it started to be massed produced, and the road and canal network was advanced enough for it to spread to the four corners.

For me, the interest comes from the fact that the earliest historical evidence for people living at my house, Cwm Dwfn, dates to the late-18th/early-19th Century. Below is the earliest map, penned by surveyor Thomas Budgen over 200 years ago in 1811 (late-Georgian; a year before Dickens was born).

You can see Cwmdwfyn in the middle, with the farmyard to the left of the 'C'. I won't say too much more about the documentary side of things as there's tonnes and I'll lose the thread; just to point out though that this is an earlier iteration of the farm, before it was re-modeled into your classic Victorian courtyard.

The other thing I'd draw your attention to is the area immediately north of the L-shaped northern boundary. Wouldn't that just be an ideal place to dump your trash for a few centuries, give the council time to devise some kind of refuse collection service? If you answered 'yes' then take a bow. That would seem to be pretty much what happened, and it's where I've been digging.

So I'd expected perhaps a few later-18th to 20th-century bits and pieces, consistent with the mapping and the late-Georgian/Victorian architecture. But I hadn't expected either the quantity and range of material that has turned up or the early date of some of it, which predates the house as mapped by some 200-300 years. So anyway, here are the more interesting pieces revealed so far, crudely arranged by type.

This is far from all of it. I'm at the halfway point in the dig and there's at least twice if not three times as much again, mainly the plain white shards in the bottom right corner. There's also plenty of more recent stuff and a good few non-pottery items of interest, chiefly glass and metal. No doubt I'll bore you with all of it in due course, but for now I'll stick to the above pottery. So what exactly are we looking at?

Disclaimer: working in archaeology does give you a good grasp of pottery types and dates etc. But there are those within the community who are true pottery experts; the sort of people who can chew the corner off a shard, date it to the decade (sometimes to the individual potter!), and identify e.g. where the clay was dug from, before swallowing it whole and asking for more. Most of us can't, and that includes me. So in the interest of full disclosure, what follows is an informed but pretty general overview.

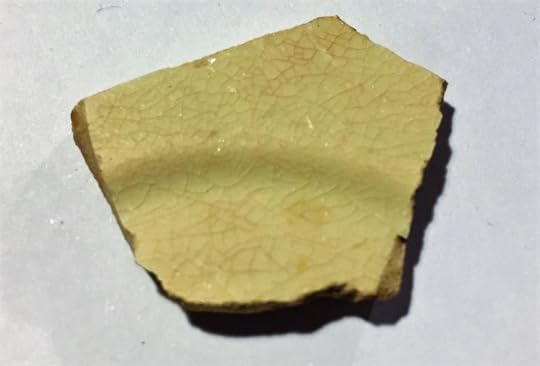

Top left are the older (late-16th-/17th- century) pieces. These are shards of 'red earthenware', which was crude and robust, made for utility rather than display. The vessels were often glazed, more usually on the inside, so that they could hold liquid. The green and pale film is a lead-glaze, probably with added copper. The little grit-like inclusions you can see in the clay are known as 'temper', added to strengthen the vessel. I can be pretty certain that most of these shards, including that below are tempered with crushed gravel and imported from North Devon. Care to guess the name? If you said 'North Devon Gravel-Tempered Ware' then take another bow.

The above was produced from the 1550s onwards and was common throughout the 17th Century, alongside the adjacent brown lead-glazes. The pieces with a much darker glaze (below) developed as a variant during the later-17th Century, with notable output from the Staffordshire kilns; this black-glazed red earthenware was typically glazed on both sides, with the dark colour resulting from the addition of manganese.

In addition to these coarse utilitarian styles a range of finer wares started to be produced during the same late-16th/17th- century time period, in an attempt to rival the imports of Chinese porcelain. Practically every piece on the right half of the first photograph (the group shot) above falls into this category. Yes, it looks like 'china', but it's tin-glazed English 'delftware'.

First produced in Holland and originally known as 'Galleyware', numerous delftware production centres were soon established in Britain and, circumstantially, the pieces at Cwm Dwfn are likely to have come from Bristol. I seem to have found three main styles. The first is effectively porcelain imitation: blue on white chinoiserie decoration:

The second is a polychromatic painted style, with naive floral patterning. I have to say that this is my favourite; looks like the sort of thing I'd have produced aged 7:

The third is the standard plain white variety, which is by far the most common (literally buckets-full of this stuff is turning up):

Delftware was produced throughout the 18th Century, but by around 1750 it was being increasingly replaced by 'Slip-wares' and styles such as 'Creamware', a good example of which is below:

Fine ware pottery, decorated with a clay slip (coloured clay suspension) rather than a glaze, became increasingly ornate from the second half of the 18th Century. Several types have turned up so far. The first is so-called 'Tortoise Shell Ware', with its beautiful diffuse polychromatic finish:

The other is possibly the highest status pottery that I've turned up so far. Thin, with a lustrous black glaze, it is known as 'Jackfield Type Ware'. While it originated in Jackfield, Shropshire, the pieces I've recovered are more likely to have been manufactured at the Staffordshire potteries. Even after being buried in the earth for nearly 300 years it is still incredibly beautiful (check out the gold enamel):

Probably the second most common thing I'm finding after the tin-glazed or delft ware is brown-glazed red ware, variously known as 'Treacle Ware' and 'Rockingham Ware' amongst other variants. First produced in the second half of the 18th Century, it remained popular throughout the 19th.

Also from the 19th Century, there's plenty of stoneware, a robust hard-fired utilitarian fabric, which became pretty much ubiquitous:

Later shards that I've recovered include transitional white ware, chinoiserie transfer-printed ware, Pearlware, and hard- and soft- paste English Porcelain. The sorts of things that you will find most commonly in antiques stores.

So there we are. A representative domestic assemblage spanning the later-16th to 20th Centuries. Half a century of life and death at Cwm Dwfn. And I'm only halfway through the dig.

Lots more to come...

April 12, 2020

Lockdown Diaries: End of Week 3

It's the end of week 3 on lockdown and the virus has drawn in...

Until yesterday I was aware that a couple of my many colleagues (nobody I work closely with) had been affected. A friend of mine had also developed the symptoms some weeks ago, and while they didn't enjoy the experience in particular their symptoms were comparatively mild and they quickly recovered. Ditto a cousin of mine and her partner. So while C-19 hasn't been entirely absent from my inner circle, it has largely remained on the periphery; infrequent, mild and no cause for alarm.

Then things changed. Yesterday, I found out that a close friend of mine, who I have known since I was 8 or 9 years old, has contracted the virus and is seriously ill. For context, this is a healthy and comparatively fit guy in his 30s, who (like me) had maintained a very high level of fitness throughout his 20s. Regardless, the virus has leveled him. He developed all the classic symptoms, including a fever, sore throat and cough. And then last week he started struggling to breath.

He developed pneumonia. The symptoms were so severe in fact that clinicians suspected one of his lungs had collapsed; thankfully it seems not, though the test results are out and who knows what the effects will be on his long-term health. I spoke to him yesterday afternoon and frankly he didn't sound like my friend of 30 years. He sounded more like a 90-year-old man. His voice lacked any sense of energy, and he clearly struggled to breath throughout our conversation.

Usually I can't get him off the phone. Yesterday I could only talk to him for a couple of minutes (literally). It was exhausting for him and I could hear his breathing getting increasingly worse. He just wanted to sleep. During the course of the brief conversation he described to me his other symptoms: headache, sickness, a complete lack of energy, an inability to walk, an inability to swallow, muscle pain, pain breathing, double-vision and more. Today is apparently his best day for some time, however, and fingers crossed he should be entering the recovery phase of this highly unpredictable illness. I can only hope that he is; while he's a jerk sometimes (no, he won't mind me saying so even now + aren't we all!), he's also a loyal and lifelong friend who I'm lucky to know.

Out in the wider world, one of the main events has been none other than UK Prime Minister Bojo himself. Probably the most high-profile person to suffer with Covid-19, his situation has been followed closely, not just in Britain but internationally. And it's not difficult to understand why. Whether or not we voted for him, love him or hate him, he is our elected representative here. The fact that he has been infected with a currently incurable, potentially life-threatening virus that has reduced practically the entire planet to its knees, is of course highly significant.

The combined government updates and media coverage has been interesting to watch. Bojo's symptoms were reportedly 'mild' at first. Then they were 'persistent'. Then he was hospitalised. Then, all of a sudden, he was in intensive care. The government went to great lengths to impress upon the public that he was not on a ventilator. Why? Because being on a ventilator means that your lungs have failed and a machine is required to breath for you. It means that, but for modern technology, you would almost certainly be dead. Translation: you are in very deep sh*t.

Beyond the personal, the significance (and sensitive treatment) of Bojo's plight reflects the fact that it is of course highly symbolic. As a figurehead he represents Britain on the international stage. And to some extent his C-19 struggle or 'curve' might be seen to reflect the process of affliction nationally - mild (nothing to worry about), then persistent (hmm... perhaps we should take action), then deadly serious on a societal scale ('oh sh*t!').

A triumph over C-19 by Bojo, as now seems likely, would be a story of national triumph. Succumbing to C-19, a national tragedy. We are told that he is now in recovery. In this respect, I'd suggest that if his recovery continues and he does return to full health, the press won't be able to resist portraying him as the embodiment of our nation (bulldog caricatures anyone??) and how together we will show the virus 'what for!' or [insert Etonian call to arms here]. It will be equated by some at least with the gradual downturn on the national curve that we are all hoping for.

Another key talking point this week has been the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) situation, so protective masks, overalls, gloves etc. In essence, these things are in short supply as demand has soared beyond their manufacturers' wildest imagination. Many countries have even banned international exports of PPE in order to serve their own domestic agenda. The health secretary then caused additional controversy by advising front-line NHS staff not to 'over-use' PPE. It is yet another tricky situation that C-19 has pitched us at short notice.

And the issues with PPE go beyond procurement, to include its practicality, comfort and use. These may seem secondary considerations, petty even, when lives are at stake. But as someone who worked in the construction industry for a decade, they seem anything but secondary to me, and my heart really does go out to front-line NHS workers suddenly finding themselves drowning in PPE on top of everything else.

PPE is mass-produced, not individually tailored. It is uncomfortable, inconvenient and imperfectly proportioned. I've been in situations where I've had to wear PPE boots, trousers, long-sleeve shirts, overalls, gloves, goggles, ear plugs and a hard-hat either all at the same time or in various combinations. On one notable occasion, this PPE code was strictly enforced for 12 hours a day, 6.5 days a week for months on end, and during a prolonged heatwave.

Honestly? PPE can drive you spare. It doesn't fit properly. It makes you overheat, it impedes your mobility, it impedes your senses of sight, hearing and touch, it distracts you, and it rubs the living sh*t out of your skin. In essence, it can make doing your job that much more awkward. So please, if you haven't already, join me in adding this to the gigantic list of things to thank our nurses and MDs for.

Work-wise, as predicted, a number of people in my department have now been furloughed. But for the large part, the company seems to be weathering the C-19 storm reasonably well so far... I've actually been on annual leave this week, giving the paperback version of COLONY a final once over before it is released next week!! I've also been digging the sh*t out of my garden (as those of you who follow me on Twitter will no doubt be aware). But don't worry, I'll bang on about that in another blog, and for now leave you all in peace. #takecare #staysafe #StayatHome

April 3, 2020

Lockdown Diaries: End of Week 2

So, have we all got cabin fever yet?

If not then STAY AT HOME!

Week 2 ends and what has it brought to the party? Would it be too cliche to say nothing and everything? I've had a lot of debates online this week about the facts and figures that are being bandied around by the media, not least the now all-too-familiar daily death toll. This is something we've had to get used to very quickly in peacetime; a daily feed of the number of people who have sadly died while being treated for Covid-19.

The question on a lot of people's lips though (including mine) seems to be 'how many of those people would have died anyway?' After all, the vast majority, as we're told, had underlying health issues and were pretty old. As part of a recent Facebook discussion I came down on the following:

"The ONS has total deaths in 2018 as 541,580 or 1,504 deaths per day on average. On 1st April 2020, 152,979 people had been tested for C-19, of which 29,474 were confirmed positive, which is 19.2%. The people tested are likely to be those at higher risk at the moment (nurses, MPs?!?! etc.), as we know, so this is likely to overestimate the infection rate amongst the general population. But lets use it anyway and extrapolate...

The UK population is 67.8 million, 19.2% of which is 12.8 million people infected. 1% of the infected = 128,820 deaths. If we divide that by 360 we get an average of 357.8 deaths per day. The average number of deaths per day according to ONS is 1,504, so this probable over-estimate of 357.8 = 24% of the average daily death toll.

What we still don't know though is how many of those 357.8 people who had C-19 in their system when they passed away would likely have died that day anyway. Are they on top of the 1,504, included within the 1,504, or partially within the 1,504? If the latter, then how partially? What are the numbers? At present, those in the know seem less interested in broadcasting this than the daily C-19 death toll. Perhaps they just don't know.

The other thing that has loomed large this week has been the word 'furlough'. I'd never heard it before, and I suspect that most people hadn't. Now it's a thing. I work in the heritage sector, which includes commercial or development-led archaeology. While unconfirmed, I have heard that 75% of the archaeology workforce has now been furloughed. And this isn't surprising.

The archaeology industry is founded on itinerant workers on short-term, rolling contracts. Those on permanent contracts, known as 'core staff', are comparatively low-paid and eminently expendable. Added to this insecurity, the industry itself is frankly at the arse-end of the construction process. Why? Because - not without irony - it doesn't tend to produce anything of monetary value. It is in fact an incomprehensible waste of time and resources to many in the construction industry; in many senses the antithesis of commercial endeavour.

So whenever the sh*t hits the economic fan, archaeology takes a hammering. It happened in 2008, when there were massive industry-wide lay-offs (I was subject to the redundancy process, but luckily survived), and it's happening again now. Only this time, we have the government's 80% of salary pledge, which has thankfully tipped the balance from redundancy to furlough. I now work in consultancy, which has a higher degree of job security. But even we are not immune. Furlough is the hot topic, and I have little doubt that the next fortnight will see colleagues and potentially myself faced with it.

On the flip-side, family-wise this last week has been pretty positive for us. My wife has engaged with the boys (and not just of necessity) perhaps more than she ever has since they were babies. She's been following the online curriculum provided by the school, but also doing her own enviably creative thing with them. This has included tapping into their love of / obsession with Minecraft, and creating a series of Minecraft mini-magazines for them, which are effectively narrative lessons. I'm impressed and incredibly proud, and I've never loved her more.

In addition, I've been making more time to play with the boys as well. They've been helping me out with digging vegetable patches (blog forthcoming) and also playing football with me. The older one - Ethan (6) - has suddenly become very good at it, and earlier today he genuinely stuck 7 of 10 shots past me. Okay, I'm old and a load of sh*t in goal, but it's not that many weeks ago that he could barely kick the ball. Ted (4) continues to punch me in the dick at every opportunity and then laugh uproariously.

So in sum, Week 2 has been very much a mixed bag. We've settled into the routine of lockdown fairly well, but there are still things taking place within the world beyond that we are powerless to resist. There are more questions than answers still at this stage, despite the fact that the situation is that much more familiar.

I have to say though that I have rarely felt more connected to other people. There is something in our vulnerability that connects us at a very basic level. It heightens the relevance and benefit of our interactions and in many ways makes us more of a community than we ever are in times of plenty. My prediction? Week 3 will bring much the same, if a little more restlessness. But maybe, just maybe, by the end of the week the light at the end of the C-19 tunnel will be that much brighter.

March 27, 2020

Lockdown Diaries: End of Week 1

It's been a strange week for us all.

Personally, I've enjoyed the best part of 40 years of unrestricted access to the outside world. I also spent a sizable proportion of those four decades watching sci-fi movies about apocalyptic plagues, the likes of: Outbreak, 28 Days Later, I am Legend, 12 Monkeys, The Andromeda Strain, and Warm Bodies.

Evidently the current situation with C-19 is a million miles away from zombie apocalypse, or even just 'normal' apocalypse; I have no doubt that it's a shot across the bow, that we'll be through it soon enough and that we'll (fingers crossed) learn from it.

Buuuutttt..... it's still the nearest thing that I, and probably most people born after 1950, have ever experienced to social dystopia.

Earlier today I headed out, for the first time this week, to do our family shop. Where I would usually have jumped in the car and sped off without ceremony or second thought, today I adopted a different ritual. For a start, I didn't just try and memorise what my wife was telling me to get, while all the time relying on the contingency that I could phone her if I forgot and she could text me any additional stuff. Instead I took a list, and I also spent some time considering which order I was likely to encounter the items in, so to minimise my time in the store. I also briefly considered what I would say to the cops if I was challenged on being out in public. Kafka anyone??

For entirely sentimental reasons, I then said goodbye to everyone, kissed my wife and hugged my boys. Why? I've no idea. It just felt as if I was about to take a risk and I needed to express it somehow. Then I washed my hands(!), before hopping in the car and taking off.

At the shops I parked as close as possible and moved, if not quickly, then at least with greater purpose than usual. I put on a pair of disposable plastic gloves that I'd schemed from the adjacent fuel station; it didn't seem a weird thing to do, others were doing exactly the same, and nobody else batted an eyelid.

I couldn't just enter the store as usual of course. The crowds of early morning numpty stockpilers had made sure of that. Instead there was a 'queuing aisle' defined by temporary barriers, which I had to navigate first. And once inside it was a sombre experience. The store was virtually empty and those who were inside were wondering up and down the aisles like wraiths, uncertain where they were meant to be, highly suspicious of one another. I joined them.

Perhaps the most sobering moment was when I rounded the end of one aisle to be confronted by a line of four fellow shoppers each wearing a face mask, spaced the regulation two meters from one another and with the same pensive look in their eyes. It actually stopped me dead in my tracks. Why? Because I'd seen similar things before. In films.

I made it out alive. And overall I was pretty comforted by the experience. Why? The store was open. There was no shortage of supplies. Yes there were quantity limits, but these were well in excess of what the average person would need. The store had adapted, providing social distancing measures and cues, protective equipment for its shelf-stackers and protective screens for its checkout staff.

Most of all though there was no panic amongst my fellow shoppers. It was business as usual, with all the typical acts of courtesy, just at greater distance. Hope springs eternal.

And when I got home my first action was to wash my hands thoroughly. It's a strange thing, but in a time before C-19 this would have been a sensible thing to do anyway after visiting a public place where people routinely pick everything up, inspect it and then put it back. And yet we never would have. Will we now?

I won't bang on about the other things that we've done this week as a family. That's for another blog. But I'll finish by saying that I've learnt a great deal more about being human, and what it is to be human, this last week than I have for a long time.

Week 2 of lockdown has got a lot to live up to.

March 22, 2020

Digging for Victory: Part 1

A momentous decision was made this morning. One that will no doubt have serious ramifications for my family and I for years to come...

I'm going to start growing some vegetables.

Before anybody leaps to the assumption that I've joined the panic about food supply in the face of C-19, I haven't. But it has got me thinking about / re-assessing quite a few things. And one of those things is food, which also happens to be one of my favourite topics more generally.

In late 2018, my family and I moved from the south Midlands to South Wales. To be honest, the exact chain of events that led to us moving has already faded from memory, but we basically wanted a change and a bit more space for the boys to grow up in. Mission accomplished. It's a smallholding in the hills north of the Towy valley in Carmarthenshire, not far from Brechfa Forest. The people who owned the property before us were livestock farmers, and they evidently also grew a lot of veg. So much of it in fact that it grows out of my lawn like some kind of weed. At least that's how I'd been thinking about it until recently...

There's nothing quite like a row of empty shelves at a supermarket to bring home to you quite how complacent you are about the range and availability of food. As an archaeologist I spend a lot of time talking about subsistence; the change from hunting and gathering during the Mesolithic to transhumance and cultivation during the Neolithic / Early bronze Age, followed by the massive agricultural expansion of the Later Bronze Age and Iron Ages. In a nutshell, this latter set the tone for the mixed agricultural lifestyle and settlement patterns that persisted here in Britain through until the Industrial Revolution.

And why does subsistence loom so large in our history? Because it was fundamental to our survival. The crops failed and there was a fair chance you were going to starve. The herds disappeared and you were going to lose some serious weight. Where did you build your village? Adjacent to the most fertile soils and widest resource base, ideally on a gentle south-facing slope overlooking a watercourse, above the floodplain. Why did you live in a longhouse? So that you could shelter your cows at one end during winter. Life was all about food and ensuring a steady supply.

Fast forward to today, and the change is stark. Most of us (at least in the west) take our full bellies more or less for granted. To use myself as an example, as I fast approach 40 I can hand on heart say that I have never grown a carrot. I think I may have grown about 10cm squared of cress in a small tub when I was at school. But even that might just be me mis-remembering someone else doing it while I was in the general area. Wheat? No chance. Barley? Forget about it. Hay? Surely hay? It's just grass forgodsake! Nope.

So this morning the above struck me, and with the full force of its 38 year absence from my MO. Like a man possessed, I pulled my boots on, grabbed a spade and garden fork and made a start. It was never my intention to plough the entire area over and start again. Let's be honest. My horticultural pedigree ruled that out from the start. Instead I went with the 'why re-invent the wheel' strategy and spent the first half hour wondering around and working out what the hell was actually growing out of my lawn. This is what confronted me (brace yourself):

Yes, that is a moss-covered path at the bottom of the shot, which tells you all you need to know about my relationship with the garden to that point. Anyway, it turns out there were quite a few different things on the grow, including rhubarb, asparagus, strawberries and cabbage. I picked on rhubarb (don't ask).

Now, as an avid gardener (!) this state of affairs plainly wasn't good enough for my prize rhubarb. So I started removing the surrounding turf and using it to define the edge of the bed.

When I'd slugged all of the turf off, I used the garden fork to dig a good half foot of soil up across the whole bed, turn it over and mash it up into... wait for it... a fine 'tilth'. First time I've ever had cause to use that word.

Job done. Don't get me wrong - I appreciate that it's a modest result at best after 4 or 5 hours of graft, and nothing to write home about for a seasoned horticulturalist. But for somebody that's never grown anything before, I'll take it. And it's also a work in progress. My plan is to create a new bed, pretty much on the same scale, each week from now until I've got the whole lawn covered. Wish me luck...

The next thing I've got to decide is whether to go with carrots, butternut squash, parsnips or spinach in this particular patch. I'm leaning towards butternut squash, but in the interest of keeping things interactive I'm open to suggestions? Carrots, butternut squash, parsnips or spinach? Whichever gets the most votes from those of you who follow my blog is the one that I'll plant, so speak now or forever hold your peas.

March 20, 2020

Unqualified re-marks?

It's March 20th 2020, and there have been a lot of big announcements today. The employment safeguards being put in place to help people through this unprecedented period of mass quarantine are pretty huge. We finally know who society's 'key workers' are. School's are out. Indefinitely. And SAGE have waded in with timescales on how long we can expect our lives to resemble some kind of sci-fi dystopia.

But one of the smaller (?) things that's stood out for me today is the strategy for grading those students who are now unable to take their G.C.S.E. exams. Why this out of all the other headlines? Let's have a look at what's proposed.

The idea is that teachers, rather than objective exam board markers, will grade their students in the relevant subject areas. So a maths teacher, for example, will look at his students, consider the aptitude they've shown, previous test scores, number of apples on the desk, and myriad other factors, and then assign them a grade.

Sounds reasonable? Well, to be honest I'm not so sure...

If there's one thing we're all getting schooled in hard at the moment, it's the fact that we are masters of under-estimation. C-19 is only the latest in a long and shameful repertoire of 'wars' we've thought would be over by Xmas. Notwithstanding actual wars (which, let's face it, are never over by Xmas, if ever), we thought that Brexit would be a breeze. That HS2 would come in on budget. That we could sell each other insurance that we didn't really need without consequence. That we could go ahead and pump toxic fumes into the atmosphere decade after decade, bury our refuse and fill the oceans with micro-plastic beads. That egomaniacs the likes of Donald Trump could never (with a public mandate) move into The Whitehouse and re-invigorate the US coal industry.

Add to that my own personal experience. It goes without saying that kids mature at different rates. But it's not just their intelligence and knowledge that mature. It's their readiness to apply their intelligence and knowledge as well. And that is a significant distinction.

Where I look back on education now and see it as the amazing opportunity that it is, pre-sixteen I was your classic 80s/90s schoolkid. I just didn't want to be there. I wanted to be riding my bike, playing football in the park, collecting stickers or trading cards. Just about anything in fact that didn't involve being dressed in a uniform, herded from room to room, forced to think about things I found boring, surrounded by other kids eager to take the p*ss out of me if I spoke or acted differently.

So it's fair to say that I didn't really take my education seriously until the eleventh hour. School was something that I had to do. Not something I ever wanted to do and succeed at. Perhaps it was just me. But somehow, having been there at the time, I don't think so. To put it bluntly, I screwed around pretty much throughout my time at school. I had fun. I acted the clown. I made a load of life-long friends. And I wouldn't have done it any differently. It enhanced my life in those respects and bequeathed me a heap of good memories that still, to this day, bring a smile to my lips.

If my teachers had had to grade me a year ahead of taking my G.C.S.E. exams, I have no doubt that I would've been down a grade on what I actually achieved in most if not all subjects. Why? Because in that strange and indefinable way that life has of steering us in particular directions, those last few months were precisely the ones in which I morphed from a B-grade student into an A-/A* grade one. Turns out I just needed to focus and get my head in the game, and it was that run up to the exams that allowed that transition to occur.

So how many present-day kids are going to fall into that same model on aggregate? Probably not too many, I agree. But I also think more than you'd imagine. I accept still not a high proportion, and don't get me wrong - I don't have any better solutions to this particular issue. The strategy suggested may be optimum. Who knows. But regardless, I do feel the need to give voice to those kids who were always going to pull out all the stops at the final exam hurdle, and whose full potential is now to be underestimated.

March 18, 2020

2020 - stranger than fiction?

It's not often in the life of a thriller writer that real life events trump the horrors you have in store for your lead protagonist. But the present comes as close as I can remember.

When it first emerged late in 2019, the virus (Covid-19) was something typically remote; it was at a comfortable enough remove not to unduly concern those of us brought up on a diet of depraved US high school mass shootings and senseless suicide bomb attacks in the middle east. If not as regular, the emergence of a virus in the markets of Wuhan was at least predictable, if not ignorable.

I've seen first hand the filthy, unregulated markets in China, where animals (literally meat in fur packaging), stuffed into cages barely bigger than their frames, are stacked high and without a second thought by people too poor to care, with inadequate sanitation. These are hellish places, breeding grounds for everything from abhorrence and inhumanity to germs. They are the perfect petri dishes for organisms without a shred of compassion.

We watched the virus spread through China and into Korea. Then into Europe; as much a psychological as a physical breakout. Perhaps the clearest example of how unprepared the western world was to find itself center stage is Italy, where both the infection rate and death toll still far exceed that of any other country outside China, due in no small part to western complacency.

Now of course it's at home in the UK. We're having daily emergency broadcasts from the government. Boris Johnson stands there in front of two Union Jacks, flanked by high ranking officials, prescribing and proscribing as never before in peacetime. Perhaps most tellingly for Brits, all talk of Brexit has disappeared overnight after three years of incessant media coverage and public debate.

Having listened to my own parents' accounts of post-war rationing, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the 80s depression, I always imagined that I too would one day sit down and regale (bore?) my own kids with stories of crises endured. It is telling though that I'd always imagined doing so when they were fully grown (as I was). I'm not equating this virus with the severity of any of those events; time has still to tell in that respect. But in all honesty I never envisaged having to explain to my six year old that his school was closing indefinitely in an attempt to stop the spread of germs that would otherwise lead to the deaths (by conservative estimates) of a quarter of a million Brits.

Neither did I ever envisage a situation where practically the entire planet went into lock-down: no sporting or musical events, no holidays, no social gatherings, no education. Where people were stock-piling supplies to the extent that supermarkets had to restrict sale quantities and opening hours. Where practically every employer and employee alike in the UK would suddenly be working from home, leaving offices and streets nation-wide empty. It sounds like a dystopian film plot. Yet it's the reality for those of us alive today.

So, yeah. It's not often in the life of a thriller writer that real life events trump the horrors you have in store for your lead protagonist. But no matter how many bullets I have fired at him, no matter how many times I have him stabbed, or how many times I have punches land squarely on his nose, I have to say that in March 2020 I'd still think twice about looking up from the page.