Walter Mosley's Blog, page 7

June 14, 2016

Not So Easy Being Rawlins

Veteran storyteller Walter Mosley is back with another installment in the life and times of Easy Rawlins in Charcoal Joe. This is terrific news on several fronts: Easy is one of the finest characters in modern-day suspense fiction, complex and artfully drawn; the heroes and villains change sides with some regularity, including the main character; and the story offers more than its share of twists and turns to confound the reader. The titular Charcoal Joe is something of a legend in the circles of Los Angeles bad guys. Easy has stayed outside Joe’s sphere, but all that changes when he is tapped by his longtime frenemy Mouse to look into the murder charges against a young friend of Joe. Violence raises its ugly head, and our hero must take some serious evasive action to protect the lives of his family and loved ones. The Easy Rawlins saga has followed the landlord-turned-detective from the early post-World War II years through the Jim Crow 1950s and up to 1968 in this latest installment. The late ’60s were tumultuous times in Southern California, and Mosley deftly weaves social commentary into the narrative.

Veteran storyteller Walter Mosley is back with another installment in the life and times of Easy Rawlins in Charcoal Joe. This is terrific news on several fronts: Easy is one of the finest characters in modern-day suspense fiction, complex and artfully drawn; the heroes and villains change sides with some regularity, including the main character; and the story offers more than its share of twists and turns to confound the reader. The titular Charcoal Joe is something of a legend in the circles of Los Angeles bad guys. Easy has stayed outside Joe’s sphere, but all that changes when he is tapped by his longtime frenemy Mouse to look into the murder charges against a young friend of Joe. Violence raises its ugly head, and our hero must take some serious evasive action to protect the lives of his family and loved ones. The Easy Rawlins saga has followed the landlord-turned-detective from the early post-World War II years through the Jim Crow 1950s and up to 1968 in this latest installment. The late ’60s were tumultuous times in Southern California, and Mosley deftly weaves social commentary into the narrative.

(via bookpage.com)

This week’s must-read books

Charcoal Joe by Walter Mosley

(Doubleday)

In Mosley’s latest Easy Rawlins mystery, it’s 1968 Los Angeles and Easy is working at a new detective agency. He meets Rufus Tyler, an old man everyone calls Charcoal Joe, who tells Easy about a young physicist, Dr. Seymour Braithwaite, who’s been arrested for murder — and asks Easy to clear his name. Soon, Easy’s life is falling to pieces around him, again.

(via nypost.com)

Oprah.com’s 60 Must-Read Books of the Summer: Charcoal Joe

What are you in the mood to read this summer? This year boasts an unusual volume of stories exploring the thrilling and thorny stuff that makes us human. We think of them as books that make a difference—every one of them worth the plunge!

Charcoal Joe

By Walter Mosley

320 pages; Doubleday

Available at: Amazon.com | Barnes & Noble | iBooks |IndieBound

It’s never easy being Easy Rawlins, especially when his main squeeze, Bonnie, cuts and runs just when he’s ready to pop the question. Next thing he knows, murder and intrigue are afoot, and we’re cruising the City of Angels in ’68, chock-full of degenerates, a few backsliding do-gooders, and everything in between. This is the 14th installment in Mosley’s celebrated mystery series. We say keep ’em coming.

Walter Mosley on Tennessee Ernie Ford’s ‘Sixteen Tons’

Walter Mosley, 64, is the author of 50 books, including his latest Easy Rawlins mystery, “Charcoal Joe” (Doubleday). He spoke with Marc Myers.

My father was a custodian in the Los Angeles public school system, and my mother worked for the Board of Education in human resources. In 1958, when I was 6, I’d stay after school with a woman named Margaret who worked for my father as a janitor. That’s when I first heard Tennessee Ernie Ford sing “Sixteen Tons.”

At Margaret’s house in South Central L.A., the television was always on. When I quit running around, I’d sit on the floor to watch. Ford had his own TV variety show on NBC every Thursday. Even as a kid, I found him captivating.

A white singer, Ford was relaxed and spoke like a congenial good ol’ boy. You could hear the South in his deep voice. Everybody I was around was originally from the South, so Ford’s sound was familiar and comforting.

After I heard him sing “Sixteen Tons” on TV, I couldn’t shake it. Many people have the same reaction. I think it’s Ford’s snapping on the second and fourth beats and his delivery, as if he had personally experienced the lyrics.

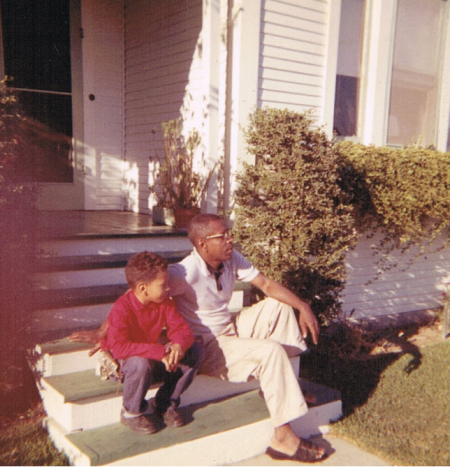

Finishing His Sentences

by Walter Mosley

Two thousand sixteen marks the 100-year anniversary of my father, Leroy Mosley’s, birth. He was and is my inspiration, the man who taught me to bob and weave in life and art. I came into being shaped by the stories about his childhood in Louisiana and the grinding poverty he endured there, the bloodletting and laughter in the Fifth Ward in Houston and the harsh enlightenment he received in the Army.

My father was born in the middle of one world war and served in the next, but his true battles, like those of so many African-Americans, were fought closer to home. Rural life in southern Louisiana was a threnody of destitution and racial oppression. But Leroy and his two half sisters were protected and fed by family that loved them and strangers who understood their pain. In the Old South, subjugation brought out the generosity in many of those persecuted, and black folk were masters of making something from nothing, be it that day’s jambalaya or a suit of clothes stitched together from rags.

Leroy named me for a ghost, a fiction — after his father, who had committed a mysterious and terrible crime back in Tennessee and went by the alias Walter Mosley. Walter was a logger and would leave for weeks at a time, working on crews hewing trees and floating them downriver to New Orleans. The boy was close to his mother, the fount of warmth in the home. She died when he was only 7, and shortly after, Walter went to work one day and never returned. Leroy’s half sisters were shuffled off to their blood mother’s relatives, and he was left to live with cousins who mistreated him. At 8 years old he jumped a freight train headed for Houston, where his mother’s father was purported to live.

The two didn’t get along. Leroy was permitted to sleep on the porch, but he had to find his own food and money. He grew up quickly in the Fifth Ward, learning to carry two guns and one razor at all times. He could fight hard and run fast, cook and sew, clean, do carpentry and fix any engine. He learned to type and write, and he was a masterful storyteller. But that’s not unusual for poor people living under the thumb of history: My Jewish relatives from Eastern Europe were no different; they’d sit up all night regaling one another with the horrors they had survived.

It was Leroy’s dream to write for the popular pulp magazines. He even sent a cowboy story to a magazine — only to see it published a year later, under someone else’s name. He gave up. It was not possible, he concluded, for an impoverished black man in the Deep South to become a writer at that time. It’s hardly easier now.

But it took World War II for my father to truly quit the South. When he realized that more of his draft-age friends had died back in Houston than in the war, he headed for Los Angeles. There, he met and married my mother and became a fiercely loving father who prepared our every meal. When I was 13, I asked him what he wanted me to be when I grew up. He said he wanted me to do whatever I wanted, that he had no directive. I took his lessons from poverty and decided to become an artist — someone who makes something from nothing. I decided to make something from the stuff of his stories, of pedestrian, tragic life, like the time he decided to eat at an all-white cafe in the late 1940s. Making it as far as the counter, he ordered a tuna melt. “That sandwich tasted like freedom,” he told me. But suddenly the white man sitting next to him dropped dead. “I realized right then and there that, freedom aside, no man, no matter who he is, can escape his death.”

My father’s life intersected with a century of conflict, horror and invention. He deciphered these histories for me, making me his scribe in a new century. My successes were his successes, and his stories thrum in every word I write. He taught me to see like a writer, to be attentive to the stories that spring up everywhere: the epileptic guy on the corner medicating his condition with wine; the man lamenting his cheating wife; a woman passing by, sheltering a child in her arms; to say nothing of his own tales — Leroy came to own three apartment buildings, but his tenants assumed he was the handyman. It’s an attentiveness to the world, to ordinary suffering, to the love that persists in its midst. My sense of the world, of history and humanity flows from this awareness — and the attendant grim humor — my father used as his guiding lamp in the darkness cast by racism and poverty.

He was riddled with cancer the last few times I saw him. On one such day, my mother and I were leaving the house in her car. My father, who we were told was too sick to stand, had somehow made it to the back porch. As we drove off, I saw him leaning heavily against the banister. But when we made eye contact, he suddenly smiled and lifted his hand. This was his gift to me: an indomitable spirit and the talent of taking the beauty and refusing the rest.

Walter Mosley is the author of more than 50 books, including the Easy Rawlins mystery series, and the recipient of PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award. His most recent novel, “Charcoal Joe,” was just published.

A version of this article appears in print on June 19, 2016, on page BR25 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: Finishing His Sentences.

The New Easy Rawlins Novel, Charcoal Joe, with Author Walter Mosley

June 12, 2016

‘Charcoal Joe”: Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins is on the case

By Steve Novak,

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Walter Mosley’s private investigator Easy Rawlins has been around for nearly three decades now. Readers first met him in “Devil in a Blue Dress” when he agrees to find a missing person. The task that begins as a lark proves an inspiration to the recent World War II veteran that he may have found a suitable occupation. He takes to the streets of Los Angeles in the early 1940s and feels his way to an unexpected career.

Mr. Mosley’s 14th Easy Rawlins mystery, “Charcoal Joe,” shows just how far the character has come since that first case. With money he garnered from his last case, “Rose Gold” (2014), he has started his own private investigation agency, complete with two associates. As he walks to his new office, Easy realizes just what has happened to his life.

“I took in a deep breath through my nostrils and smiled, thinking that a poor black man from the deep South like myself was lucky not to be dead and buried, much less a living, breathing independent businessman,” he thinks.

Easy’s new agency doesn’t mean old friends stop relying on him. One of his oldest friends is Raymond “Mouse” Alexander. Early in the new novel, Mouse asks Easy for a favor, telling the investigator that the son of an acquaintance of his has been wrongfully charged with double homicide.

Mr. Mosley gives the reader a lot to chew on in setting up the favor. The accused murderer is a young black man, a graduate student at Stanford University, and has no prior police record. The homicide victims have ties to the Los Angeles crime world of the early 1960s. The man who wants Easy Rawlins to clear the accused is Charcoal Joe, a legendary black mobster currently in jail.

Easy is quickly wedged between a rock and a hard place. Doing a favor for a gangster can be hazardous to one’s health, no matter if you succeed or fail. Still, Easy is committed to the case for no other reason than to do a favor for Mouse.

Mr. Mosley always gives the Easy Rawlins novels a thorough description of black life and culture in the Los Angeles area in the 1950s and the 1960s. Much like Raymond Chandler did in his portrait of Southern California for his fictional private eye Philip Marlowe, or Dashiell Hammett did with Sam Spade, Mr. Mosley takes readers into the worlds of everyone from psychopathic criminals to business magnates, along with the minor players such as con men, tipsters, career criminals and cops. Each book is a triptych to another part of Easy Rawlins’ world.

The use of the first-person narrative in mysteries and private investigator novels has a long history. Inveterate readers of mystery stories can easily rattle off names of dozens of writers who have used this style. However, it remains a difficult genre if you really want to catch and hold the reader’s attention. Nearly anyone can write introductory chapters about being called into solve a case, but it takes a craftsman to create a fictional world where you can picture the people and the places in the investigator’s world.

Mr. Mosley works on a wide canvas when he sketches the principal characters in his novels. Before Rawlins ever meets Charcoal Joe, he already has heard enough stories about him that the reader can picture a willful and violent man who is feared by anyone who encounters him. Joe’s subsequent actions only enforce this view.

Easy Rawlins’ worldview is one that’s essential to any successful detective: You have to care but not show it. You have to listen but not always believe what you’re hearing. You have to keep going where others have already stopped and turned back.

Despite the hefty criminal history that Charcoal Joe carries, he finally admits to Easy that he has respect and confidence in his ability to clear the young man of the murder charges. Joe knows that Easy has considerable street cred of his own.

“If I was gonna double cross somebody, it sure as hell wouldn’t be you,” Joe tells Rawlins. “You’re one of the most dangerous men in Southern California.”

Fans will be glad to know that another dangerous man, Fearless Jones, makes several appearances in this novel. Jones is another of Mr. Mosley’s characters, featured in three stand-alone novels as the main character.

The entertainment value of Mr. Mosley’s latest book doesn’t rule out a corresponding educational side. In the era in which Mr. Mosley sets the story, it was very difficult for a black man to work within the confines of a legal and judicial system that was overwhelmingly white and biased. More than anything else, Easy Rawlins is a man alone, making his own path that others may later follow.

Steve Novak is a freelance writer living in Cleveland.

June 10, 2016

Walter Mosley’s ‘Charcoal Joe’: Easy Rawlins is back

By Neely Tucker

The Washington Post

Walter Mosley’s latest Easy Rawlins novel, “Charcoal Joe,” comes on the heels of the author winning the Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America in April. No one familiar with the quality and quantity of Mosley’s creative output was surprised by this honor. His output encompasses more than four dozen books — including 14 Rawlins novels — science fiction, nonfiction and essays. He’s been awarded PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

Still, in some ways, the full measure of his achievement can only be gauged by seeing him at the Edgars, as the Mystery Writers’ honors are known. I watched the whole thing from a table near the back. Mosley was one of fewer than two dozen African Americans in a ballroom holding hundreds. Publishing, like the film industry, was a pale field when Mosley’s first Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins novel, “Devil in a Blue Dress,” was published in 1990 and made into a Denzel Washington vehicle five years later. Two decades on, both still are. (Looking at you, #oscarssowhite.)

So it’ s no surprise that Mosley, an L.A. native whose father migrated out west from Louisiana, is attuned to the uneasy America that blacks inhabit. The fictional Easy, a child of New Iberia, La., who migrates to Los Angeles, is too. The central twist in “Devil,” set in 1948 L.A., turns on the different worlds that whites and blacks inhabit in the same place. “Charcoal Joe,” set in the same city exactly two decades later, finds that things are different, if not all that much improved.

Mosley’s L.A. has many of the mean streets that Raymond Chandler made iconic, but these are different streets and they are mean for different reasons. Here’s Easy, narrating a crosstown drive in 1968 in “Charcoal:”

“It’s a long way from West L.A. to Watts. It’s the same city but a darkness descends as you progress eastward. You pass from white dreams into black and brown realities. There were many miles to cover but distance was the least of it. It was another world, where I was going.”

Chandler’s novels and James Ellroy’s “L.A. Quartet” both covered the same city and era — the 1940s and 1950s — but neither offered any real insight into the black side of town. Think of the wrongly charged black suspects in Ellroy’s brilliant “L.A. Confidential,” for example. The black guys are there as a plot complication. The detectives really don’t pay any price for blowing them away. If Easy had investigated? That would have been the story, full stop.

As “Charcoal Joe” opens, we find Easy in a good place. He’s flush with cash from a previous case. He’s going to propose to his girlfriend. He’s down to one smoke per day. Racial progress has been enough that he can enroll his daughter, Feather, in a posh private school in the white side of town. And he’s been able to open a three-man firm in a building that seems a metaphor for the city: Once an elegant residence for a rich white guy, it’s been cut up into three businesses. The first floor is an antique store of faded quality. The second floor, run by the landlord, is a Japanese family-owned and -operated insurance brokerage. Easy’s new three-man detective agency — one Jewish partner and one black — is on the third. Two of the couples working in the building are interracial.

Likewise, the murder that forms the spine of the narrative is racially complicated. “A white man named Peter Boughman and some other guy named Ducky” were shot to death in a house in Malibu, Rawlins’s longtime friend Raymond “Mouse” Alexander tells him. Seymour Brathwaite, a well-to-do black postgraduate student at UCLA, lived nearby, heard the shots and went to investigate, Mouse says. Brathwaite was found standing beside the bodies when the police came. He had no gun but was booked for murder.

The hitch is that Brathwaite is the son of a friend of the fearsome Rufus Tyler, a.k.a. Charcoal Joe, an elderly black man, who is good at cards, killing people and Getting Stuff Done. Charcoal, who has done Easy a favor in the past, now wants to call in his tab.

As the novel progresses, you’ll notice that Mosley embraces the great nicknames of black men of a certain reputation, as immortalized by Chester “The Real Cool Killers” Himes. Easy. Whisper. Charcoal. Cully Grindman. Himes had a cop named “Gravedigger Jones.” Easy has a friend named “Fearless Jones.”

And as with Himes, you can’t color-code for good and bad guys. Early on, Easy has to deal with a racist white motorcycle cop. Later, at a Rodeo Drive jewelry store named Precieux Blanc (Precious White ), he and Fearless meet a black guard who refuses to let them enter. Easy pegs him for an ex-cop, now working in “white stores so that black customers who were followed and rousted could not complain about racism.”

Easy, not amused, asks the guard: “. . .Should me and Fearless here paint us some protest signs and march up and down sayin’ that you don’t serve blacks up in here?”

Things you have to love about Mosley’s use of the dialect: “paint us some,” “up in here.”

If you’ve read Mosley before, you know that Easy is probably going to figure things out by the end, though at a cost. But like the crosstown drive from West L.A. to Watts, you don’t hop in the car with Easy Rawlins for the destination. You ride shotgun for the trip.

Neely Tucker, a national reporter for The Washington Post, is the author of “Only the Hunted Run: A Sully Carter Novel,” which will be published in August.

June 9, 2016

Summertime, and the living is EZ

By David Prestidge

By David Prestidge

Crime Fiction Lover

On the Radar — Ezekiel ‘Easy’ Rawlins returns this week for another neon-lit adventure among the hills and boulevards of Los Angeles. We’ve also got a new printing of Dashiell Hammett’s short stories, and a great selection of further crime novels to try.

Charcoal Joe, by Walter Mosley

PI Easy Rawlins doesn’t look for trouble but when his old friend, the lethal hitman nicknamed Mouse asks for help, he knows that trouble will soon be looking for him. Mouse isn’t a man who takes no for an answer, and soon Rawlins, trying to help the man they call Charcoal Joe, is doing his best to avoid hits from all directions on the glitzy streets of LA. In our back pages you can read our PI Case Files on Mosley’s most memorable creation. Out on 16 June.

May 19, 2016

Charcoal Joe

An Easy Rawlins Mystery

An Easy Rawlins MysteryAvailable: June 14, 2016

About the Book: Walter Mosley’s indelible detective Easy Rawlins is back, with a new detective agency and a new mystery to solve.

Picking up where his last adventures inRose Gold left off in L.A. in the late 1960s, Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins finds his life in transition. He’s ready—finally—to propose to his girlfriend, Bonnie Shay, and start a life together. And he’s taken the money he got from the Rose Gold case and, together with two partners, Saul Lynx and Tinsford “Whisper” Natly, has started a new detective agency. But, inevitably, a case gets in the way: Easy’s friend Mouse introduces him to Rufus Tyler, a very old man everyone calls Charcoal Joe. Joe’s friend’s son, Seymour (young, bright, top of his class in physics at Stanford), has been arrested and charged with the murder of a white man from Redondo Beach. Joe tells Easy he will pay and pay well to see this young man exonerated, but seeing as how Seymour literally was found standing over the man’s dead body at his cabin home, and considering the racially charged motives seemingly behind the murder, that might prove to be a tall order.

Between his new company, a heart that should be broken but is not, a whole raft of new bad guys on his tail, and a bad odor that surrounds Charcoal Joe, Easy has his hands full, his horizons askew, and his life in shambles around his feet.

Walter Mosley's Blog

- Walter Mosley's profile

- 3853 followers