Walter Mosley's Blog, page 2

December 1, 2020

Blood Grove

Walter Mosley’s infamous detective Easy Rawlins is back, with a new mystery to solve on the sun-soaked streets of Southern California.

Ezekiel “Easy” Porterhouse Rawlins is an unlicensed private investigator turned hard-boiled detective always willing to do what it takes to get things done in the racially charged, dark underbelly of Los Angeles.

But when Easy is approached by a shell-shocked Vietnam War veteran—a young white man who claims to have gotten into a fight protecting a white woman from a black man—he knows he shouldn’t take the case.

Though he sees nothing but trouble in the brooding ex-soldier’s eyes, Easy, a vet himself, feels a kinship form between them. Easy embarks on an investigation that takes him from mountaintops to the desert, through South Central and into sex clubs and the homes of the fabulously wealthy, facing hippies, the mob, and old friends perhaps more dangerous than anyone else.

Set against the social and political upheaval of the late 1960s, Blood Grove is ultimately a story about survival, not only of the body but also the soul.

Widely hailed as “incomparable” (Chicago Tribune) and “dazzling” (Tampa Bay Times), Walter Mosley proves that he’s at the top of his game in this bold return to the endlessly entertaining series that has kept fans on their toes for years.

Blood Grove – Available: February 2, 2021

Walter Mosley’s infamous detective Easy Rawlins is back, with a new mystery to solve on the sun-soaked streets of Southern California.

Ezekiel “Easy” Porterhouse Rawlins is an unlicensed private investigator turned hard-boiled detective always willing to do what it takes to get things done in the racially charged, dark underbelly of Los Angeles.

But when Easy is approached by a shell-shocked Vietnam War veteran—a young white man who claims to have gotten into a fight protecting a white woman from a black man—he knows he shouldn’t take the case.

Though he sees nothing but trouble in the brooding ex-soldier’s eyes, Easy, a vet himself, feels a kinship form between them. Easy embarks on an investigation that takes him from mountaintops to the desert, through South Central and into sex clubs and the homes of the fabulously wealthy, facing hippies, the mob, and old friends perhaps more dangerous than anyone else.

Set against the social and political upheaval of the late 1960s, Blood Grove is ultimately a story about survival, not only of the body but also the soul.

Widely hailed as “incomparable” (Chicago Tribune) and “dazzling” (Tampa Bay Times), Walter Mosley proves that he’s at the top of his game in this bold return to the endlessly entertaining series that has kept fans on their toes for years.

September 10, 2020

National Book Foundation to present Lifetime Achievement Award to Walter Mosley

The National Book Foundation, presenter of the National Book Awards, announced that it will award Walter Mosley with the 2020 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (DCAL). Mosley has written more than sixty critically acclaimed books across subject, genre, and category. Walter Mosley’s 1990 debut novel Devil in a Blue Dress was the first in the bestselling mystery series featuring detective Easy Rawlins, and launched Mosley into literary prominence. Mosley’s books have been translated into twenty-five languages, and he has won numerous awards, including, but not limited to, an Edgar Award for Down the River Unto the Sea, an O. Henry Award, The Mystery Writers of America’s Grand Master Award, a Grammy®, several NAACP Image awards, and PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2020, he was named the recipient of the Robert Kirsch Award for lifetime achievement from the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. The DCAL will be presented to Mosley by two-time National Book Award Finalist Edwidge Danticat.

The National Book Foundation, presenter of the National Book Awards, announced that it will award Walter Mosley with the 2020 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (DCAL). Mosley has written more than sixty critically acclaimed books across subject, genre, and category. Walter Mosley’s 1990 debut novel Devil in a Blue Dress was the first in the bestselling mystery series featuring detective Easy Rawlins, and launched Mosley into literary prominence. Mosley’s books have been translated into twenty-five languages, and he has won numerous awards, including, but not limited to, an Edgar Award for Down the River Unto the Sea, an O. Henry Award, The Mystery Writers of America’s Grand Master Award, a Grammy®, several NAACP Image awards, and PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2020, he was named the recipient of the Robert Kirsch Award for lifetime achievement from the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. The DCAL will be presented to Mosley by two-time National Book Award Finalist Edwidge Danticat.

“Mosley is a master of craft and narrative, and through his incredibly vibrant and diverse body of work, our literary heritage has truly been enriched,” said David Steinberger, Chair of the Board of Directors of the National Book Foundation. “From mysteries to literary fiction to nonfiction, Mosley’s talent and memorable characters have captivated readers everywhere, and the Foundation is proud to honor such an illustrious voice whose work will be enjoyed for years to come.”

Born in Los Angeles in 1952, Mosley’s limitless imagination has fueled the creation of novels, plays, conscious-raising nonfiction, and more, and his boundless drive has often pushed him to publish two or more books a year. In addition to the many awards and accolades he has received over the years, several of his books have been adapted for film and television including Devil in a Blue Dress, released in 1995, starring Denzel Washington, Don Cheadle, and Jennifer Beals. His nonfiction writing has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and The Nation among other publications. Mosley is also a writer and an executive producer on the John Singleton FX drama series, “Snowfall.”

“Mosley is undeniably prolific, but what sets his work apart is his examination of both complex issues and intimate realities through the lens of characters in his fiction, as well as his accomplished historical narrative works and essays,” said Lisa Lucas, Executive Director of the National Book Foundation. “His oeuvre and his lived experience are distinctly part of the American experience. And as such, his contributions to our culture make him more than worthy of the Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.”

Mosley is the thirty-third recipient of the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, which was created in 1988 to recognize a lifetime of literary achievement. Previous recipients include Edmund White, Isabel Allende, Annie Proulx, Robert A. Caro, John Ashbery, Judy Blume, Don DeLillo, Joan Didion, E.L. Doctorow, Maxine Hong Kingston, Stephen King, Ursula K. Le Guin, Elmore Leonard, Norman Mailer, Toni Morrison, and Adrienne Rich. Nominations for the DCAL medal are made by former National Book Award Winners, Finalists, judges, and other writers and literary professionals from around the country. The final selection is made by the National Book Foundation’s Board of Directors. Recipients of the Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters receive $10,000 and a solid brass medal.

ABOUT WALTER MOSLEY

Walter Mosley is one of the most versatile and admired writers in America. He is the author of more than sixty critically acclaimed books that cover a wide range of ideas, genres, and forms including fiction (literary, mystery, and science fiction), political monographs, writing guides including Elements of Fiction, a memoir in paintings, and a young adult novel called 47. His work has been translated into twenty-five languages,

From a forthcoming collection of short stories, The Awkward Black Man, to his daring novel John Woman, which explored deconstructionist history, and his standalone crime novel Down the River Unto the Sea, which won an Edgar Award for Best Novel, the rich storylines that Mosley has created deepen the understanding and appreciation of Black life in the United States. He has introduced an indelible cast of characters into the American canon starting with his first novel, Devil in a Blue Dress, which brought Easy Rawlins, his private detective in postwar Los Angeles and his friends Jackson Blue and Raymond “Mouse” Alexander into reader’s lives. Mosley has explored both large issues and intimate realities through the lens of characters like the Black philosopher Socrates Fortlow; the elder suffering from Alzheimer’s, Ptolemy Grey; the bluesman R L; the boxer and New York private investigator Leonid McGill; the porn star of Debbie Doesn’t Do It Anymore Debbie Dare; and Tempest Landry and his struggling angel, among many others.

Mosley has also written and staged several plays including The Fall of Heaven, based on his Tempest Landry stories and directed by the acclaimed director Marion McClinton. Several of his books have been adapted for film and television including Devil in a Blue Dress (starring Denzel Washington, Don Cheadle and Jennifer Beals) and the HBO production of Always Outnumbered (starring Laurence Fishburne and Natalie Cole). His short fiction has been widely published, and his nonfiction—long-form essays and op-eds—have appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and The Nation among other publications. He is also a writer and an executive producer on the John Singleton FX drama series, “Snowfall.”

Concerned by the lack of diversity in all levels of publishing, in 1998 Mosley established The Publishing Certificate Program with the City University of New York to bring together book professionals and students hailing from a wide range of racial, ethnic, and economic communities for courses, internships, and job opportunities. In 2013, Mosley was inducted into the New York State Writers Hall of Fame, and he is the winner of numerous awards, including an O. Henry Award, The Mystery Writers of America’s Grand Master Award, a Grammy®, several NAACP Image awards, and PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2020, he was named the recipient of the Robert Kirsch Award for lifetime achievement from Los Angeles Times Festival of Books.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Mosley now lives in Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

Walter Mosley to receive honorary National Book Award

FILE – Author Walter Mosley attends the 2018 National Art Awards in New York on Oct. 22, 2018. Mosley, who is among the most acclaimed crime novelists of his time, is receiving an honorary National Book Award. He will formally receive the medal during a Nov. 18 ceremony that will be held online because of the coronavirus pandemic. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP, File)

NEW YORK (AP) — Walter Mosley is receiving an honorary National Book Award, cited for dozens of books which range from science fiction and erotica to the acclaimed mystery series that has followed the life of Los Angeles private detective Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins.

The 68-year-old Mosley, whose works include the novels “Devil In a Blue Dress” and “Down the River Unto the Sea” and the nonfiction “Twelve Steps Toward Political Revelation,” has won the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, which has been given to Toni Morrison, Robert Caro and Arthur Miller among others. The National Book Awards are presented by the non-profit National Book Foundation.

The first Black man to win the lifetime achievement medal in its 32 year history, Mosley is among the most acclaimed crime novelists of his time, even if he rejects being called anything but a writer. He has received numerous prizes, from an Edgar Award for best mystery novel to an O. Henry prize for short stories to a Grammy for his liner notes to the Richard Pryor anthology “… And It’s Deep Too!” He is also well known to National Book Awards officials, having formerly served on the Foundation’s board of directors and once hosting the awards ceremony. But like such previous medal winners as Ray Bradbury and Elmore Leonard, he has never been nominated for a National Book Award in a competitive category.

Mosley knows well the reason: Crime fiction is usually bypassed when lists for a year’s best books are considered.

“I mean the genres are treated like something else, not real literature,” he said during a recent telephone interview from his home in Los Angeles.

In a statement Thursday, National Book Foundation Executive Director Lisa Lucas noted the quantity, and quality, of Mosley’s work.

“Mosley is undeniably prolific, but what sets his work apart is his examination of both complex issues and intimate realities through the lens of characters in his fiction, as well as his accomplished historical narrative works and essays,” Lucas said. “His oeuvre and his lived experience are distinctly part of the American experience. And as such, his contributions to our culture make him more than worthy of the Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.”

Mosley doesn’t see himself as a crime novelist even when he’s writing about Rawlins, through whom he has explored Los Angeles and the country in the post-World War II era. He thinks of his books less for their plots than for the composite view they offer of Black men in the U.S., or more specifically Black heroes, whether Rawlins, the philosopher Socrates Fortlow or the mail clerk in the short story, “Pet Fly,” part of his upcoming collection “The Awkward Black Man.”

“When I think about writers like Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald, I don’t like those writers because they are crime writers but because of what they tell me about people. In my own work, I’m actually trying to understand human nature,” he says, adding that he considers “The Awkward Black Man” a showcase for “Black characters who don’t make it into the stories we tell.”

As always, Mosley is busy working on future books, including another Easy Rawlins novel, set in Los Angeles during the late 1960s. It’s a chance for Mosley to revisit an era of protests against the Vietnam War, and to see it through the perspective of Rawlins, a World War II veteran.

“Easy changes as he gets older and the world changes, so dealing with that world becomes a different thing,” Mosley says. “I’m always writing about something new and my character hopefully has some things to say. When I started working on the Rawlins novels, I had been talking about my father, but after (the 2007 novel) ‘Blonde Faith’ I realized I was talking about myself.”

Mosley will formally receive the medal during a Nov. 18 ceremony that will be held online because of the coronavirus pandemic. Mosley’s friend and fellow author Edwidge Danticat will introduce him. The Foundation also will honor Carolyn Reidy, the late CEO of Simon & Schuster, who will be given the Literarian Award for outstanding service on behalf of books and reading.

(via AP

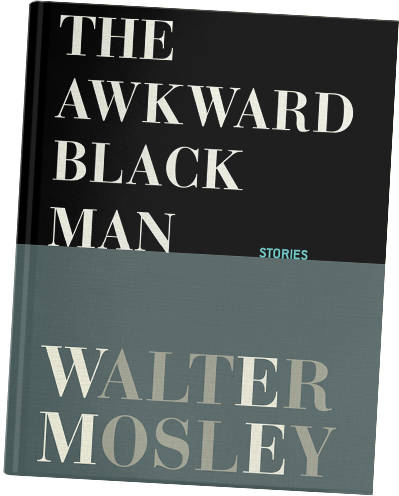

The Awkward Black Man

“In this collection of simple and complex portraits of a wide range of Black men, Mosley…defies the stereotypical images that abound in American culture…present[ing] an array of men in varying circumstances facing racism, obstructed opportunities, and other terrors of modern life, including climate change, natural and manmade disasters, homelessness, urban violence, and failed relationships . . . Master storyteller Mosley has created a beautiful collection about Black men who are, indeed, awkward in their poignant humanity.” —Booklist (starred review)

“The tough-minded and tenderly observant Mosley style remains constant throughout these stories even as they display varied approaches from the gothic to the surreal. The range and virtuosity of these stories make this Mosley’s most adventurous and, maybe, best book.” –Kirkus Reviews

Praise for Walter Mosley:

“When reviewing a book by Walter Mosley, it’s hard not to simply quote all the great lines. There are so many of them. You want to share the pleasures of Mosley’s jazz-inflected dialogue and the moody, descriptive passages reminiscent of Raymond Chandler at his best.”―Washington Post, on Down the River Unto the Sea

“With Mosley, there’s always the surprise factor ― a cutting image or a bracing line of dialogue.”―New York Times Book Review, on And Sometimes I Wonder About You

“Mosley is the Gogol of the African-American working class ― the chronicler par excellence of the tragic and the absurd.”―Vibe

“[Mosley] has a special talent for touching upon these sticky questions of evil and responsibility without getting stuck in them.”―New Yorker

Across his wide-ranging literary career, bestselling and award-winning author Walter Mosley has proven himself a master of narrative tension, both with his extraordinary fiction and gripping writing for television. THE AWKWARD BLACK MAN (Grove Press; Publication Date: September 15, 2020, $26.00 Hardcover; ISBN-13 978-0-8021-4956-5) collects seventeen of Mosley’s most accomplished short stories to showcase the full range of his remarkable talent.

Mosley presents distinct characters as they struggle to move through the world in each of these stories—heroes who are awkward, nerdy, self-defeating, self-involved, and, on the whole, odd. He overturns the stereotypes that corral black male characters and paints a subtle, powerful portrait of each of these unique individuals. In “The Good News Is,” a man’s insecurity about his weight gives way to a serious illness and the intense loneliness that accompanies it. Deeply vulnerable, he allows himself to be taken advantage of in return for a little human comfort in a raw display of true need. “Pet Fly,” previously published in the New Yorker, follows a man working as a mailroom clerk for a big company—a solitary job for which he is overqualified—and the unforeseen repercussions he endures when he attempts to forge a connection beyond the one he has with the fly buzzing around his apartment. And “Almost Alyce” chronicles failed loves, family loss, alcoholism, and a Zen approach to the art of begging that proves surprisingly effective.

Touching and contemplative, each of these unexpected stories offers the best of one of our most gifted writers.

January 6, 2020

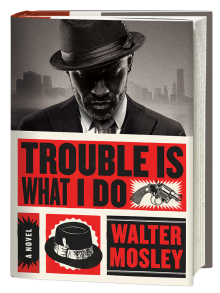

Trouble is What I Do

Morally ambiguous P.I. Leonid McGill is back — and investigating crimes against society’s most downtrodden — in this installment of the beloved detective series from an Edgar Award-winning and bestselling crime novelist.

Morally ambiguous P.I. Leonid McGill is back — and investigating crimes against society’s most downtrodden — in this installment of the beloved detective series from an Edgar Award-winning and bestselling crime novelist.

Leonid McGill’s spent a lifetime building up his reputation in the New York investigative scene. His seemingly infallible instinct and inside knowledge of the crime world make him the ideal man to help when Phillip Worry comes knocking.

Phillip “Catfish” Worry is a 92-year-old Mississippi bluesman who needs Leonid’s help with a simple task: deliver a letter revealing the black lineage of a wealthy heiress and her corrupt father. Unsurprisingly, the opportunity to do a simple favor while shocking the prevailing elite is too much for Leonid to resist.

But when a famed and feared assassin puts a hit on Catfish, Leonid has no choice but to confront the ghost of his own felonious past. Working to protect his client and his own family, Leonid must reach the heiress on the eve of her wedding before her powerful father kills those who hold their family’s secret.

Joined by a team of young and tough aspiring investigators, Leonid must gain the trust of wary socialites, outsmart vengeful thugs, and, above all, serve the truth — no matter the cost.

November 7, 2019

Walter Mosley on the fantasy of Whiteness and how Dubya was worse than Trump

Walter Mosley is one of America’s greatest crime-fiction writers. He is the author of almost 50 books across multiple genres including the bestselling mystery series featuring detective Easy Rawlins. Mosley’s essays on politics and culture have appeared in many leading publications, most notably The New York Times Magazine and The Nation. In September the New York Times featured his widely read op-ed “Why I Quit the Writers’ Room”.

Walter Mosley is one of America’s greatest crime-fiction writers. He is the author of almost 50 books across multiple genres including the bestselling mystery series featuring detective Easy Rawlins. Mosley’s essays on politics and culture have appeared in many leading publications, most notably The New York Times Magazine and The Nation. In September the New York Times featured his widely read op-ed “Why I Quit the Writers’ Room”.

Mosley is also a writer and consulting producer on the FX period crime drama “Snowfall,” which recently wrapped its third season (Seasons 1 and 2 are currently streaming on Hulu) and has been renewed for a fourth.

He has also earned numerous awards including the PEN America’s Lifetime Achievement Award, a Grammy, and an O. Henry Award. His newest book is “Elements of Fiction,” a follow-up to his instructional book, “This Year You Write Your Novel” (2007).

In this wide-ranging conversation, Walter Mosley reflects on his relationship with the late John Singleton, the cultural impact of Singleton’s film “Boyz n the Hood,” and their collaboration on the TV Series “Snowfall.” Mosley also offers a critical perspective on the fantasies of Whiteness and the Age of Trump.

The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What is your writing routine now? Are you still doing the three to four hours a day?

I never go to four. But yes, three hours in the morning. I actually find that most people write in the morning, anybody who’s been at it for a long time. I remember [late science fiction author] Octavia Butler would go home in the evening from work and go to sleep at eight and then wake up at four in the morning and write then. Some people I know write at night or they just write in spurts. But most people who write every day that I know do it in the morning.

September 28, 2019

An Uncomfortable Conversation In The Writers’ Room

Editor’s note: This story includes language some may find offensive. We’ve chosen to leave Mosley’s direct quotes uncensored here, in the broadcast, and in the podcast version of this interview. For a censored version of this episode, go here. For a censored version of this transcript, read the WPR.org version.

It hadn’t occurred to novelist and screenwriter Walter Mosley that what happened in the writers’ room could find its way into a human resources department memo. But when a polite human resources representative called him on the phone to ask why he’d said the “N-word” during a story meeting, he responded, “I am the N-word in the writers’ room.”

Later, he wrote about his experience in an op-ed for the New York Times.

At that moment, Mosley realized he was done working in that room — the sense of trust between writers was shattered. He quit the job that same day.

“How can I exercise these freedoms when my place of employment tells me that my job is on the line if I say a word that makes somebody, an unknown person, uncomfortable?” Mosley wrote.

Mosley said true and complete freedom of expression is a key feature of American culture. That means that we might be made uncomfortable from time to time, but Mosley argues that those should be moments of discussion and debate, not an occasion to email human resources.

He spoke to Charles Monroe-Kane of “To the Best of Our Knowledge” about what happened after that fateful phone call, and why no one should have dominion over what words we can use.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Charles Monroe-Kane: When you got that phone call, how did you feel?

Walter Mosley: It’s kind of surprising to hear somebody who probably was a white person, who definitely represented an institution run by white men, calling up a black man and telling him that he can’t refer to the language that suppressed him and his for four centuries.

I thought “Wow, that’s crazy.”

And then as I thought about it more, I said this is attacking everybody — it’s not just me. It’s an attack against the freedom of speech — all of a sudden there’s somebody in your office somewhere who can say, “If you say something we don’t like, we can fire you.”

CMK: It was just a warning, right? They weren’t going to ask you to apologize or anything.

WM: But you know how HR works, right? You say (something happened) “one time,” then something else happens, and then something else happens. You know, you have to say, “Well, we’re thinking about getting rid of this person. So we have to start working on it.”

CMK: They’re building the paperwork, the Walter paperwork.

WM: Exactly. They can’t just fire you like that. They have to call me. They have to talk to me about it in order to fire me.

Now listen, they might not have ever fired me, but I can’t work in a writers’ room where people are so sensitive that if I say something just explaining an experience, that they’re going to snitch on me.

I couldn’t work in the room anymore anyway. My freedom of expression was gone.

And believe me, I don’t just think this is true in (the) writers’ room. I think that anywhere — if somebody is talking, telling a story, responding to stimulus in the world around them — we have to at least consider the freedom of expression. Does me being uncomfortable mean you lose your constitutional rights? That’s an important question.

I know what the Constitution says. I can’t yell fire in a crowded theater. I can’t use language to attack, bully, or harass a person. But that doesn’t mean I can’t use language, and language is open to everybody.

That’s part of being an American. A big part of being an American.

CMK: What I don’t understand is context. I mean, what if you’re writing on the show, and the C-word is a part of what is happening? Maybe you’re showing that is wrong inside the show, and that’s the way you want to go as writers, right?

WM: Oh, I can write in the script. I just can’t say it. Which, by-the-by, is worse than the word.

“N-word” is worse than “nigger.” Because “N-word” makes it acceptable, you know? It’s never gonna be acceptable to say, “Well that nigger did this,” but (to say), “Well, you know, the N-word.” Well so that sounds OK, actually. And I don’t want it to sound OK. That’s why I use the real word, not the hyphenated word.

And of course, a lot of black people will argue, “But what if a white person said it?” And I said that if they said it trying to attack or insult or harass me, that’s a problem. But if they said it the way I just said it, I can’t get on them. I live in America. No, I wouldn’t like it, but there are certain things you have to accept in America.

I’m a black man in America. We are some of the original people in America after the Native Americans. We came way back at the beginning of time. And this is my country. And me and my people are part of the creation of that country. And part of that creation is the Constitution.

CMK: As an artist, how does that make you feel?

WM: I was upset when the person was talking to me on the phone. But later after I quit — and I realized that it’s OK that I quit — I felt good being able to have that conversation. Because what’s most important is that we discuss who and what we are. So the absolute opposite of human resources — we actually sit and discuss something.

I don’t need HR to say, “Well, if you keep on making people uncomfortable, we’re going to fire you.”

I don’t need that. That’s not helping me. Nobody learns anything from that.

But if I get to talk to somebody and I say, “Well, I felt this” and they say, “Well, we feel that,” then yeah, I’m going to learn something, right?

But this is not about learning something. This is about “obey me,” Joseph McCarthy says, “or you’re going to go into jail. You’re going to lose your job. You’re going to be out the country.”

I’m like, wow. You feel you can just say this to me, do this to me, and it’s OK because those are the rules? You know, this is Hannah Arendt talking about “the banality of evil.”

CMK: But as writers, if everyone starts censoring themselves for a politically correct culture, then it diminishes the art.

WM: There’s no question about it.

Now listen, all writers’ rooms are not like this, but almost all HR rooms are like this. All you need is one person to say, “I felt uncomfortable. I didn’t feel safe.”

And listen: I’m not saying that’s invalid. But how one deals with it becomes the issue.

CMK: I want art — especially with words — to push me. I want to be made uncomfortable. Isn’t that the point of good art, of good films, of good TV? It’s to push us so that we can grow as a culture. I don’t think that’s happening right now because people are afraid to even write it.

WM: Listen, you don’t want to get back to the place in the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s when all the people in a writers’ room were white men. You don’t wanna get to that point.

The room I was sitting in, there were four women in the room. There were three black people in the room. There was an Asian woman, a Native American woman. It was all over the place — that is what we need. We need people to represent.

But at the same time, there’s a lot of times I feel uncomfortable with things that people say. But I have to learn how to deal with it, either through discussion or dealing with it myself.

Someone said to me a while ago that we should outlaw the Confederate flag, and I said absolutely not. This is America. We have freedom of expression. If somebody has an American flag in their heart, I don’t mind seeing it on their forehead too. It’s OK. And that’s an important thing for me.

I’m not sitting around arguing that only black people have the right to control a certain arena of language. We all have to deal with language. We all have to deal with discomfort. We all have to learn from that and hopefully get better in dealing with each other.

September 5, 2019

Bestselling Crime Writer Walter Mosley Will Teach You How To Write A Story

BEVERLY HILLS, CA – AUGUST 06: Walter Mosley of “Snowfall” speaks during the FX segment of the 2019 Summer TCA Press Tour at The Beverly Hilton Hotel on August 6, 2019 in Beverly Hills, California. (Photo by Amy Sussman/Getty Images)

With Meghna Chakrabarti

A conversation with bestselling writer Walter Mosley about his hard-boiled character Easy Rawlins and a life in crime writing.

Guest

Walter Mosley, American novelist. He has written more than 50 books, including the major bestselling mystery series featuring Easy Rawlins. His new book is “Elements of Fiction.”

New York Times: “Walter Mosley: By the Book” — “When and where do you like to read?

“I like to read either in motion or in water. And so I am most satisfied reading on subway cars, trains, planes, ferries, boats or floating on some kind of air-filled device or raft in a pool, pond or lake. But I am happiest reading in the bathtub; lying back with my head resting on the curved end of the tub, one leg bent and the other resting along the edge. Now and then I add a little hot water with a circular motion of my toe. I decided on my apartment because it had a deep tub with water jets to massage me while I read science fiction and magical realism.

“Are you a rereader?

“Reading is rereading just as writing is rewriting. Any worthwhile book took many, many drafts to reach completion, and so it would make sense that the first time the reader works her way through the volume it’s more like a first date than a one-time encounter. If the person was uninteresting (not worthwhile) there’s no need for a repeat performance, but if they have promise, good humor, hope or just good manners, you might want to have a second sit-down, a third. There might be something irksome about that rendezvous that makes you feel that you have something to work out. There might be a hint of eroticism suggesting the possibility of a tryst or even marriage.

“The joy of reading is in the rereading; this is where you get to know the world and characters in deep and rewarding fashion.

“What makes a good mystery novel?

“This question deserves examination. I could answer by saying that in a good mystery there’s a crime and a cast of characters, any of whom may or may not have committed that crime. Readers have their suspicions, but most often they are wrong — if not about the perpetrator then about the underlying reason(s) for the commission of said crime. In a very good mystery, the detective comes into question and the investigator is forced to face his, or her, own prejudices, expectations and limitations. In a great mystery, we find that the crime being investigated reveals a deeper rot.

“But this answer only addresses, finally, the technical execution of the mystery. A good mystery has to be a good novel, and any good novel takes us on a journey where we discover, on many levels, truths about ourselves and our world in ways that are, at the same time, unexpected and familiar. If the mystery writer gives us a good mystery without a good novel to back it up, then she, or he, has failed.”

Vulture: “Walter Mosley on FX’s Snowfall, Legalizing Drugs, and His Advice for Young Writers” — “Walter Mosley is one of the greatest American crime-fiction writers. He’s the author of nearly 50 books, including 14 volumes chronicling the life of Easy Rawlins, an African-American private detective living in South Central Los Angeles. His newest job is as a writer and consultant on Snowfall, the FX drama about the effect of the crack cocaine trade on Southern California in the 1980s. The series returns to FX on July 19, and the first episode of season two will premiere at this year’s Split Screens TV Festival on June 2 at IFC Center, with Mosley in attendance.

“Ahead of the Snowfall season premiere, Mosley talked to Vulture about the difference between novel writing and TV writing, the problem of mass incarceration, why he believes all drugs should be legalized, the advice he gives young writers, and what happens when he loses a draft of something he’s working on.”

Anna Bauman produced this hour for broadcast.

This program aired on September 5, 2019. Audio will be available soon.

(via wbur.org)

August 20, 2019

Walter Mosley in Conversation with Legendary Filmmaker Walter Bernstein

I’ve known Walter Bernstein for 30 years. In all my adult life I have never met a more intelligent, loving, sensitive, questioning, heroic man. Whether putting his body in the way to block stones hurled at Paul Robeson or marching across nighttime, Nazi-dominated, Yugoslavia to be the first American to interview the insurgent Josep Broz Tito—a hero in his own right. Walter underwent LSD psycho-therapy in the 1960s and wrote some of the most beautiful scenes ever seen on the movie screens that most often lie to us. He interviewed the great Sugar Ray Robinson while riding shotgun in his pink Cadillac and worked closely with the incomparable Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte.

At once Walter is an original and a filial brother in arms. His convictions and beliefs were often dangerous for him and his loved ones. His socialism, for instance. Many of us, maybe all of us, have convictions and beliefs but how many have the courage to stand up for what we believe and behind others who have no choice but to fight? Not many I think. For this reason alone there is greatness to Mr. Bernstein.

Today, Tuesday, August 20, 2019, Walter will celebrate his 100th birthday. One hundred years fighting the good fight with his body and mind, his love of justice and an open heart. One hundred years of sharing his larder, his knowledge, and his restless pursuit of what is right in the midst of chaos, prejudice, stupidity, and downright evil. One hundred years searching for the right words and images while celebrating any and all who join in this endless, completely human adventure.

Walter agreed to a short interview concerning the previous hundred years. I didn’t ask about his parents or siblings, his elementary school experiences or his first love. Instead I talked about a life lived in a land of potentials and pitfalls.

Walter Mosley's Blog

- Walter Mosley's profile

- 3853 followers