Corey Robin's Blog, page 87

March 20, 2014

The Uncharacteristically Obtuse Mr. Chait

Jonathan Chait is no dummy. He’s one of the smartest political journalists around. So this bit of obtuseness in his critique yesterday of Ta-Nehisi Coates caught me by surprise.

Coates has been writing a series of pieces interrogating the idea of the culture of poverty, the notion that African American poverty is rooted in a deep tradition of bad values, bad behavior, bad choices, especially among black men. This idea used to be the exclusive preserve of the right; a milder version of it has since migrated to the liberal left.

In his latest dispatch, Coates wrote this:

Certainly there are cultural differences as you scale the income ladder. Living in abundance, not fearing for your children’s safety, and having decent food around will have its effect. But is the culture of West Baltimore actually less virtuous than the culture of Wall Street? I’ve seen no such evidence.

Here’s Chait in response:

Coates dismisses the culture objection in his latest piece by asking sardonically, “is the culture of West Baltimore actually less virtuous than the culture of Wall Street?” I think the example undermines his point. I have no idea how to compare Wall Street to West Baltimore, but it’s clear that Wall Street has an enormous cultural problem — which is to say it has normalized kinds of behavior that many of us consider bad.

Actually, the example undermines Chait’s point. Because Coates isn’t challenging the notion that Wall Street behavior isn’t bad or that there’s not a culture of bad behavior on Wall Street. He’s challenging the notion that it’s bad behavior, or the culture of bad behavior, that explains, in whole or in part, poverty in the black community.

All those guys on Wall Street act like jerks; yet somehow they don’t wind up poor. That’s Coates’s point. If the culture on Wall Street is not more elevated than that of West Baltimore, something other than the culture on Wall Street and the culture in West Baltimore has to explain the wealth of the one and the poverty of the other.

“The rich are different from you and me,” Fitzgerald is supposed to have said to Hemingway. “Yes,” Hemingway responded, “they have more money.” The conversation, of course, never happened. Even so, Hemingway got it right.

March 12, 2014

Further Thoughts on Nick Kristof

I have a piece up at Al Jazeera America following up on the Nick Kristof/public intellectuals kerfuffle of a few weeks back. Some highlights.

In the 1990s the philosopher and Arts & Letters Daily editor Dennis Dutton ran an annual Bad Writing contest in order to highlight turgid academic prose. If the contest were still around, this passage from The American Political Science Review might be a winner:

For a body of n members, in which there exists a group large enough and willing to pass a motion, let the members vote randomly and declare the motion passed when the mth member has voted for it, where m “yes” votes are required for passage. Define as the pivot the member in the mth position and note that there are n! (read “n factorial,” that is 1 · 2 · … · n) such random orderings of n voters (that is, the permutations of a, b, · · · , n). Then define the power, p, of a member, i, thus: pi = ti/n!, where ti is the number of times i is pivot.

As New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof recently pointed out, this is the kind of writing that has estranged the reading public from academia. A generation ago, political scientists were public intellectuals. We wrote lucid prose. We spoke to the issues of the day. We advised President John F. Kennedy. But now all we care about is math, jargon and one another.

There’s one problem with what I’ve just said. That passage from The American Political Science Review appeared in 1962, the second year of the Kennedy administration.

…

At their best, intellectuals do more than package their research into digestible bits for policymakers or the public. They force us to think beyond the limits of the day, to ask the questions no one is asking. They are an invitation to imaginative excess and political trespass. Academic experts in the mainstream media reassure us with their authority; young intellectuals in the little magazines arrest us with their divinations.

It may be, however, that the economics that make little magazines and blogs possible also make them unsustainable. Many of these outlets rely on the volunteer or nearly free labor of writers and grad students or middle-aged professors like me. The former live cheaply and pay their rent with a precarious passel of odd jobs, fellowships and university teaching; the latter have tenure.

But grad students graduate, 20-somethings make families, and rents go up. Struggling writers in 1954 could flee to tenured positions in academia; their counterparts in 2014 will find no such refuge. Nearly three-quarters of all instructional staff at colleges and universities today are not on the tenure track. They’re insecure, contingent workers, an army of cheap and casual labor that make the universities go. While young writers can afford to do the kind of intellectual journalism we see at the little magazines, older adjuncts teaching five classes can’t.

Writers and academics who fret over the fate of public intellectuals may think they are debating vital questions of the culture. But their discussions are myopically focused on the writing habits of a rapidly disappearing elite. The vast majority of potential public intellectuals do not belong to the academic 1 percent. They are not forsaking the snappy op-ed for the arcane article. They are not navigating the shoals of publish or perish. They’re grading.

March 11, 2014

David Brooks: Better In the Original German

Isaac Chotiner thinks David Brooks is not making sense. That’s because Chotiner’s reading Brooks in translation. He needs to read Brooks in the original German.

Here’s Brooks in translation:

What’s happening can be more accurately described this way: Americans have lost faith in the high politics of global affairs….American opinion is marked by an amazing sense of limitation —that there are severe restrictions on what political and military efforts can do.

…

Today people are more likely to believe that…the liberal order is not a single system organized and defended by American military strength; it’s a spontaneous network of direct people-to-people contacts, flowing along the arteries of the Internet. The real power in the world is not military or political. It is the power of individuals to withdraw their consent. In an age of global markets and global media, the power of the state and the tank, it is thought, can pale before the power of the swarms of individuals.

…

It’s frankly naïve to believe that the world’s problems can be conquered through conflict-free cooperation and that the menaces to civilization, whether in the form of Putin or Iran, can be simply not faced. It’s the utopian belief that politics and conflict are optional.

Here’s Brooks in the original German:

A world in which the possibility of war is utterly eliminated…would be a world without the distinction of friend and enemy and hence a world without politics. It is conceivable that such a world might contain many very interesting antithesis and contrasts, competitions and intrigues of every kind, but there would not be a meaningful antithesis whereby men could be required to sacrifice life, authorized to shed blood, and kill other human beings.

…

The negation of the political, which is inherent in every consistent individualism, leads necessarily to a political practice of distrust toward all conceivable political forces and forms of state and government, but never produces on its own a positive theory of state, government, and politics.

…

What this liberalism still admits of state, government, and politics is confined to securing the conditions for liberty and eliminating infringements on freedom. We thus arrive at an entire system of demilitarized and depoliticalized concepts.

…

State and politics cannot be exterminated.

American Schmittianism, alive and well.

March 4, 2014

There’s no business like Shoah business

I’ve been reading Alisa Solomon’s Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof. I can’t recommend it highly enough. I’m hoping to blog about it when I’m done, but for now, I wanted to tell this little story from the book.

In 1966, Anne Marisse, who was playing Tzeitel in Fiddler, was fired after she missed a performance on Rosh Hashanah without, the producers said, giving advance notice. Marisse’s firing proved controversial in the Jewish community. For two reasons: first, because Fiddler was a show about preserving Jewish traditions in the face of the secular (and other) demands of modernity; and second, because Sandy Koufax had refused the previous year to play in the World Series on Yom Kippur. One particularly irate man in the Bronx wrote to the producers: “Your ‘show must go on’ regardless…Six million of our people also had a ‘show’ of their own when they marched into gas chambers.”

March 2, 2014

Vanessa Redgrave at the Oscars

When I was a kid, there was probably no actor more reviled among Jews than Vanessa Redgrave. This was the late 1970s, and Redgrave was an outspoken defender of the Palestinians and a critic of Israel.

It all came to a head in 1978 at the Academy Awards (this is why I’m thinking about her tonight). Redgrave was up for an award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in Julia, a film my family refused to see (boycotts run deep with me, I guess). The Jewish Defense League was out in force that night. Apparently there had been a major campaign to deny Redgrave the Oscar on the grounds that she supported a Palestinian state. She got it anyway. Instead of offering an olive branch to her critics, or keeping quiet about the controversy, she took the opportunity of her acceptance speech to denounce the “Zionist hoodlums” who had campaigned against her nomination and possible receipt of the award.

Her speech didn’t go down so well with the audience, some of whom booed her. Later that night, the playwright and screenwriter Paddy Chayevsky used the opportunity of his presenting the award for Best Screenplay—to Woody Allen for Annie Hall (Allen, of course, has himself become the source of some controversy this year)—to denounce Redgrave for using the opportunity of her acceptance speech to make a political statement:

I would like to say—personal opinion of course—that I’m sick and tired of people exploiting the Academy Awards for the propagation of their own propaganda. I would like to suggest to Miss Redgrave that her winning the Academy Award is not a pivotal moment in history, does not require a proclamation, and a simple “thank you” would have sufficed.

Whatever you think of the protagonists, it was great theater.

Thinking back on that night tonight, I was curious to see where Redgrave wound up landing on the issue of Israel/Palestine as it presents itself today.

I did a little research and noticed that in 1986, she came out in favor of a cultural boycott of Israel. No surprise there. This position earned her no end of condemnation from defenders of Israel, including Jane Fonda, her co-star in Julia. Fonda joined Tom Hayden, her husband at the time, to say:

We are appalled at Vanessa Redgrave’s attempt to organize a cultural boycott of Israel. We urge all cultural workers to strongly oppose this vicious act and we are confident that it will be rejected by people of conscience everywhere.

In 1986, Hayden was in the California State Assembly, his eye on higher office. I have no idea if that played a role in the two making their statement.

But in 20o9, Redgrave would join Julian Schnabel and Martin Sherman to issue a denunciation of filmmakers who were protesting the Toronto Film Festival’s decision to spotlight and showcase films coming out of Tel Aviv. As Redgrave and her co-authors put it in a letter published in the New York Review of Books:

These citizens of Tel Aviv and their organizations and their cultural outlets should be applauded and encouraged. Their presence and their continued activity is reason alone to celebrate their city. Cultural exchanges almost always involve government channels. This occurs in every country. There is no way around it. We do not agree that this involvement is a reason to shun or protest, picket or boycott, or ban people who are expressing thoughts and confronting grief that, ironically, many of the protesters share.

Now she was a critic of the idea of a boycott (though in truth the filmmakers weren’t calling for a boycott; they were merely protesting this one decision). Ironically, one of the most prominent voices protesting the Toronto Film Festival’s decision was…Jane Fonda.

Since the debate over Israel and Palestine increasingly pits parents against children in the Jewish community—the most recent Pew poll, which got so much attention last fall, documents a decreasing attachment to Israel among younger Jews—I can’t end this post without posting this clip of Redgrave and her father, Michael, doing Act IV, Scene 7, from King Lear. It’s the scene of Lear’s and Cordelia’s reconciliation. Lear had unfairly banished Cordelia from the kingdom over some perceived slight, and now, slipping in and out of madness, he recognizes the terrible wrong he has done to her. He says:

You have some cause, they have not.

And in one of the most heart-breaking lines, Cordelia responds:

No cause, no cause.

That murmured protest of Cordelia—no cause, no cause—seems especially poignant in light of the ways that Israel/Palestine has divided Jewish families and the generations.

March 1, 2014

Gaza: A Tower of Babel in Reverse

The Tower of Babel is a story of the peoples of the earth, united by a common language, coming together in order to establish and preserve themselves as a unity in the sky. Gaza is a Tower of Babel in reverse. Having already cut off its residents from the rest of the world by land and by air, the Israelis built a wall to the bottom of the sea in order to seal them off entirely. Despite some periodic reversals, that isolation remains, thanks in part to the collusion of the Egyptians. Unlike its biblical predecessor, this upside-down Babel is still standing.

February 20, 2014

Backlash Barbie

We interrupt our regularly scheduled arguing about Israel to bring you a word from our digital consigliere, Laura Brahm. Laura is a freelance writer who periodically—i.e., every day—helps me figure out what I’m doing with this blog.

Apparently it’s a banner time for ambiguous feminist heroes—Beyoncé, Claire Underwood…and now, Barbie.

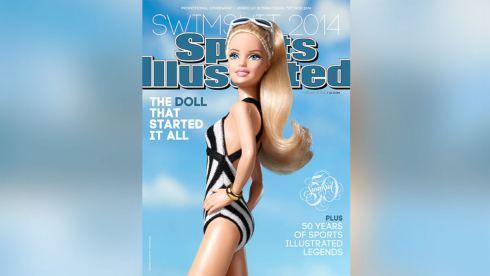

This week, she appeared on the cover of the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue. Mattel is marketing the campaign using the language of women’s empowerment (the hashtag is #unapologetic).

At first I thought this was funny and clever in a knowing, lipstick-feminism kind of way. Like Barbie was embracing her inner drag queen. But then things got ugly. In response to real live feminists who tried to rain on her beach party, Barbie took out a full page ad in the New York Times for an op-ed, “Why Posing for Sports Illustrated Suits Me.” She writes:

Upon the launch of this year’s 50th anniversary issue, there will again be buzz and debate over the validity of the women in the magazine, questioning if posing in it is a blow to female equality and self-image. In 2014, does any woman in the issue seriously need permission to appear there?

I suppose you could argue Barbie is indeed making a feminist rhetorical move here, insofar as she’s engaging in the time-honored practice of trashing other feminists. She goes on:

Ask yourself, isn’t it time we teach girls to celebrate who they are? Isn’t there room for capable and captivating? It’s time to stop boxing in potential. Be free to launch a career in a swimsuit, lead a company while gorgeous, or wear pink to an interview at MIT.

Unless that last line is targeted at boys, she’s a little off base.

There’s been no shortage of brilliant, enraged responses to this campaign. But one aspect may get overlooked in the troll-feeding frenzy.

It’s funny Barbie should use the language of careers and the workplace. If only it really were the anti-pink, non-fun-having feminists who were holding women back from achieving their dreams or even just from being pretty at the office.

But the truth is we can’t be free to celebrate who we are at work if we have no First Amendment rights there. If we are subject to “at will” employment and have no paid parental leave or flexible hours enabling us to stay home when Skipper is sick.

In short, it’s not feminists who are telling you what color you can or cannot wear to work.

As a child, I loved Barbie. I still remember the gold lamé mini-dresses and the exciting hint of the glamour of being an independent grownup woman. But with ad campaigns like this one demonizing feminists, I will never buy her for my own daughter.

So, Barbie, I agree with you that “pink is not the problem.” But before you point your insufficiently separated finger at other women, take a closer look at your boss.

February 19, 2014

James Madison and Elia Kazan: Theory and Practice

James Madison, Federalist 51:

The constant aim is…that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights.

Elia Kazan, on why he named names:

Reason 1: “I’ve got to think of my kids.”

Reason 2: “All right, I earned over $400,000 last year from theater. But Skouras [head of Twentieth-Century Fox] says I’ll never make another movie. You’ve spent your money, haven’t you? It’s easy for you. But I’ve got a stake.”

February 16, 2014

Look Who Nick Kristof’s Saving Now

For the last few months, I’ve had a draft post sitting in my dashboard listing all the words and phrases I’d like to see banished from the English language. At the top—jockeying for the #1 slot with “yummy,” “closure” and “it’s all good”—is “public intellectual.”

I used to like the phrase; it once even expressed an aspiration of mine. But in the years since Russell Jacoby wrote his polemic against the retreat of intellectuals to the ivory tower, it’s been overworked as a term of abuse.

What was originally intended as a materialist analysis of the relationship between politics, economics, and culture—Jacoby’s aim was to analyze how real changes in the economy and polity were driving intellectuals from the public square—has become little more than a rotten old chestnut that lazy journalists, pundits, and reviewers keep in their back pocket for whenever they’re short of copy. Got nothing to say? Nothing on your mind? Not to worry: here’s a beating-a-dead-horse-piece-that-writes-itself about the jargony academic who writes only for her peers in specialized journals that only a handful of people read.

To wit, Nicholas Kristof’s column in today’s New York Times:

SOME of the smartest thinkers on problems at home and around the world are university professors, but most of them just don’t matter in today’s great debates.

…

Yet it’s not just that America has marginalized some of its sharpest minds. They have also marginalized themselves.

…

But, over all, there are, I think, fewer public intellectuals on American university campuses today than a generation ago.

…

Professors today have a growing number of tools available to educate the public, from online courses to blogs to social media. Yet academics have been slow to cast pearls through Twitter and Facebook. Likewise, it was TED Talks by nonscholars that made lectures fun to watch (but I owe a shout-out to the Teaching Company’s lectures, which have enlivened our family’s car rides).

I write this in sorrow, for I considered an academic career and deeply admire the wisdom found on university campuses. So, professors, don’t cloister yourselves like medieval monks — we need you!

Those are the bookends of Kristof’s piece. In between come the usual volumes of complaint: too much jargon, too much math, too much peer review, too much left politics. Plus a few dubious qualifications (economists aren’t so bad, says Kristof, because they’re Republican-friendly…and, I guess, not jargony, math-y, or peer-review-y) and horror stories that turn out to be neither horrible nor even stories.

Erik Voeten at The Monkey Cage has already filleted the column, citing a bunch of counter-examples from political science, which is usually held up, along with literary theory, as Exhibit A of this problem.

But we also have all of us—sociologists, philosophers, historians, economists, literary critics, as well as political scientists—who write at Crooked Timber, which is often read and cited by the mainstream media. There’s Lawyers, Guns, and Money: judging by their comments thread, they have a large and devoted audience of non-academics. My cohort of close friends from graduate school write articles for newspapers and magazines all the time—or important research for think tanks that gets picked up by the mainstream media—and books that are widely reviewed in the mainstream media. (And what am I? Chopped liver?) Kristof need only open the pages of the Nation, the New York Review of Books, the London Review of Books, the Boston Review, The American Conservative, Dissent, The American Prospect—even the newspaper for which he writes: today’s Times features three opinion columns and posts by academics—to see that our public outlets are well populated by professors.

And these are just the established academics. If you look at the graduate level, the picture is even more interesting.

When I think of my favorite writers these days—the people from whom I learn the most and whose articles and posts I await most eagerly—I think of Seth Ackerman, Peter Frase, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Lili Loofbourow, Aaron Bady, Freddie de Boer, LD Burnett, Tressie McMillan Cottom, Adam Goodman, Matthijs Krul, Amy Schiller, Charles Petersen, Tom Meaney…I could go on. For a long time.

(And though Belle Waring has long since ceased to be a grad student, can someone at Book Forum or Salon or somewhere get this woman a gig? We’re talking major talent here.)

Whenever I read these folks, I have to remind myself that they’re still in grad school (or just a few months out). I sometimes think they’re way smarter than we ever were when we were in grad school. But that’s not really true. It’s simply that they’re more used to writing for public audiences—and are thus better equipped to communicate ideas in intelligible, stylish prose—than we were.

When I was in grad school, my friends and I would dream of writing essays and articles for the common reader. I remember when one of our cohort—Diane Simon—broke into The Nation with a book review (of Nadine Gordimer?) We were totally envious. And awestruck. Getting into that world seemed impossible, unless you were Gordon Wood sauntering into the New York Review of Books after having transformed your field.

The reason it seemed so difficult is that it was. There just weren’t that many outlets for that kind of writing. None of us had any contacts. More important, aside from, maybe, a local alternative weekly, there were no baby steps to take on our way to writing for those outlets. There really was no way to get from here—working on seminar papers or dissertation proposals—to there: writing brilliant essays under mastheads that once featured names like Edmund Wilson and Hannah Arendt.

I remember all too well writing an essay in the mid 1990s that I wanted to publish in one of those magazines. When I looked around, all I could see was The New Yorker, Harper’s, The New York Review, that kind of thing. I sent it everywhere, and got nowhere.

Today, it’s different. You’ve got blogs, Tumblr, Twitter, and all those little magazines of politics and culture that we’re constantly reading about in the New York Times: Jacobin, The New Inquiry, the Los Angeles Review of Books, n+1, and more, which frequently feature the work of graduate students.

Now there are all kinds of problems with this new literary economy of grad student freelancers. And from talking to graduate students today (as well as junior faculty), I’m well aware that the pressure to publish in academic venues—and counter-pressure not to publish in public venues—is all too real. Worse, in fact, than when I was in grad school. Because the job market has gotten so much worse. I often wonder and worry about the job prospects of the grad students I’ve mentioned above. Are future employers going to take a pass on them simply because they’ve written as brilliantly and edgily as they have?

Back to Kristof: Even from the limited point of view of what he’s talking about—where have all the public intellectuals gone?—he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

So what is he really talking about, then?

You begin to get a clue of what he’s really talking about, then, by noticing two of the people he approvingly cites and quotes in his critique of academia: Anne-Marie Slaughter and Jill Lepore.

Kristof holds up both women—one the former dean of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public Affairs, the other the holder of an endowed chair at Harvard—as examples of publicly engaged scholars. In addition to their academic posts, Slaughter was Obama’s Director of Policy Planning at the State Department (George Kennan’s position, once upon a time) and a frequent voice on the front pages of every major newspaper; Lepore is an immensely prolific and widely read staff writer at The New Yorker.

(Incidentally, as an editor pointed out on Facebook, Slaughter and Lepore, along with Will McCants, who Kristof also cites approvingly, are all published by Princeton University Press. So much for academic presses churning out “soporifics.”)

Now I happen to know Jill rather well. She and I first met in the summer of 1991, when she was looking for a housemate and I was looking for a temporary place to stay. I moved in for a time—one of our other housemates was Mary Renda, who would go on to write a kick-ass book on the US invasion and occupation of Haiti, which it would behoove a trigger-happy Kristof to read—and later got in on the ground floor of her dissertation. She’s a truly gifted historian.

But there are a lot of gifted historians. And only so many slots for them at The New Yorker.

The problem here is not that scholars don’t aspire to write for The New Yorker. It’s that it’s a rather selective place. Kristof says that Lepore “is an exception to everything said here.” She is, but not in the way he thinks. Or for the reasons he thinks.

If you’re flying so high up in the air—Kristof tends to look down on most situations from 30,000 feet above sea level—you’re not going to see much of anything. And Kristof doesn’t. He only reads The New Yorker, and then complains that everyone doesn’t write for The New Yorker. He doesn’t see the many men and women who are in fact writing for public audiences. Nor does he see the gatekeepers—even in our new age of blogs and little magazines—that prevent supply from meeting demand.

And to the extent that he’s right about the problem of academics publishing for other academics he doesn’t identify its real causes:

A basic challenge is that Ph.D. programs have fostered a culture that glorifies arcane unintelligibility while disdaining impact and audience. This culture of exclusivity is then transmitted to the next generation through the publish-or-perish tenure process. Rebels are too often crushed or driven away.

Not really. The problem here isn’t that typically American conceit of “culture” v. nonconformist rebel. It’s the very material pressures and constraints young academics face, long before tenure. It’s the job market. It’s the rise of adjuncts. It’s neoliberalism. Jacoby understood the material sources of the problem he diagnosed. Kristof doesn’t.

But the material dimensions of Kristof’s oversight (or lack of sight) go even deeper. When we criticize Kristof or other academics-don’t-write-for-the-public-spouting journalists, we tend to do what I’ve just done here: We point to all the academics we know who are writing in well established venues and places and cry, “Look at them! Look at me!”

But there’s an entire economy of unsung writers with PhDs who are in a far worse position: Though they want to write, and sometimes do, for a public audience, they don’t have a standing gig the way I or The Monkey Cagers do. They’re getting by on I don’t know what. And while most of the people I mentioned above, including many of the graduate students, are getting their work into fairly mid- to high-level places, these folks aren’t. Certainly not in high enough places to pay the bills or to supplement whatever it is they’re doing to get by.

Take Yasmin Nair. Yasmin’s a writer in Chicago, with a PhD from Purdue. She’s also an activist. She’s impatient, she sees things the rest of us don’t see, she’s intemperate, she’s impossible, she’s endearing, and she’s unbelievably funny. Think Pauline Kael, only way more political. (Actually, Freddie deBoer did a pretty damn good job describing her work, so read Freddie.) She’s got two essays that I think are, as pieces of prose, brilliant: “Gay Marriage Hurts My Breasts” and “Why Is America Turning to Shit?“

In my ideal world, Robert Silvers would reach down from his Olympian heights and snatch up Yasmin to write about or review, well, anything. (Didn’t that kind of happen to Kael with The New Yorker?) But that’s not going to happen.

And that not happening doesn’t even begin to describe the real challenges facing a writer like Nair. Somehow she’s got to pay the bills. But unlike professors like myself or even graduate students who’ve got fellowships or TA positions (and happen to be lucky enough to live in places with a low cost of living), at least for the time being, Yasmin doesn’t have a steady-paying gig.

This isn’t just an issue of precarity or justice; it’s intimately related to the Kristofs of this world bleating “Where have all the public intellectuals gone?” Yasmin is a public intellectual (there, I said it). But without the kinds of supports the rest of us currently have or will have in the future, her pieces in The Awl or In These Times or on her blog—which is how the rest of us academics make our beginnings in the public writing world—can’t give her the lift she needs to get her work up in the air where it belongs. Because she’s always got something else, here on the ground, on her mind: namely, how to pay the rent.

And she’s not alone. Anthony Galluzzo has a PhD in English from UCLA. He’s also been adjuncting—first at West Point, now at CUNY—for years. He’s written a mess of academic articles. Two years ago he wrote an article in Jacobin that I thought was pure genius. It was called “Sarah Lawrence, With Guns,” and it was about his experience teaching English at West Point. That’s a topic that another English professor at West Point has written about, but Anthony’s treatment has the virtue of being coruscating, funny, ironic, honest, and not boosterish. Like Mary Renda’s book, the kind of writing Kristof could profit from.

When Anthony’s piece came out, I thought to myself, “This is the beginning for him.” But it hasn’t been. Because he’s been adjuncting around the clock, sometimes without getting paid on time, and worrying about other things. Like…how to pay the rent.

I had to smile at Kristof’s nod to publish or perish. Most working academics would give anything to be confronted with that dilemma. The vast majority can’t even think of publishing; they’re too busy teaching four, five, courses a semester. As adjuncts, as community college professors, at CUNY and virtually everywhere else.

I don’t ever expect Kristof to look to the material sources of this problem; that would require him to raise the sorts of questions about contemporary capitalism that journalists of his ilk are not inclined—or paid—to raise.

But Kristof’s a fellow who likes to save the world. So maybe this is something he can do. Instead of writing about the end of public intellectuals, why not devote a column a month to unsung writers who need to be sung? Why not head over to the “Sunday Reading” at The New Inquiry, which features all the greatest writing on the internets for that week? Why not write about the Anthony Galuzzo’s and Yasmin Nair’s who deserve to be read: not as a matter of justice but for the sake of the culture? Who knows? He might even learn something.

(Special thanks to Aaron Bady for reading a draft of this post and contributing some much needed additions.)

Update (4:30)

I mentioned Boston Review in my post. But as a friend reminded me, they deserve a special shout-out. Because not only do they regularly introduce and publish academics like myself—one of my earliest and IMHO most important pieces was chosen and championed by Josh Cohen, the magazine’s editor—but they often solicit work from graduate students like Lili or Aaron and non-academically employed PhDs. So if you’ve got that gem of a piece and are wondering where to send it, send it to Boston Review.

Update (5:45)

Also, I should have said this in the piece, but this line—”He only reads The New Yorker, and then complains that everyone doesn’t write for The New Yorker.”—was something Aaron Bady wrote to me in an email. I should have quoted it and credited to it to him in the post. My apologies.

February 14, 2014

Valentine’s Day

My one requirement: that you stay with me.

I want to hear you, grumble as I may.

If you were deaf I’d need what you might say

If you were dumb I’d need what you might see.

If you were blind I’d want you in my sight

For you’re the sentry posted to my side:

We’re hardly half way through this lengthy ride

Remember we’re surrounded yet by night.

Your ‘let me lick my wounds’ is no excuse now.

Your ‘anywhere’ (not here) is no defense

There’ll be relief for you, but no release now.

You know whoever’s needed can’t go free

And you are needed urgently by me

I speak of me when us would make more sense.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers