Corey Robin's Blog, page 85

April 27, 2014

How Long Do You Have to Practice Apartheid Before You Become an Apartheid State?

The Daily Beast reports on a speech John Kerry gave to the Trilateral Commission:

The secretary of state said that if Israel doesn’t make peace soon, it could become ‘an apartheid state,’ like the old South Africa. Jewish leaders are fuming over the comparison.

South African apartheid lasted from 1948 to 1994: 46 years in total. The Occupation has lasted 47. What Jeffrey Goldberg has called Israel’s “temporary” or “provisional” apartheid is now one year older than South Africa’s “permanent” apartheid.

During the Iraq War, Thomas Friedman routinely predicted that “within the next six months,” we’d find out whether Iraq was going to be a democracy or a basket case. So recurrent were these predictions, long after the six months had expired, that it led to a fresh coinage: the Friedman Unit. Perhaps it’s time we coined a new phrase: the Goldberg Unit?

Kerry is hardly the first to make such warnings about the Occupation continuing; they have a long lineage. Just after the 1967 War, none other than David Ben-Gurion apparently warned that if the Occupation continued, Israel would become an apartheid state.

Which raises the question: How long do you have to practice apartheid before you become an apartheid state?

Has There Ever Been a Better Patron of the Arts Than the CIA?

Countering Thomas Piketty’s critique of inherited wealth, Tyler Cowen suggests that such dynastic accumulations of private wealth may be a precondition of great art:

Piketty fears the stasis and sluggishness of the rentier, but what might appear to be static blocks of wealth have done a great deal to boost dynamic productivity. Piketty’s own book was published by the Belknap Press imprint of Harvard University Press, which received its initial funding in the form of a 1949 bequest from Waldron Phoenix Belknap, Jr., an architect and art historian who inherited a good deal of money from his father, a vice president of Bankers Trust. (The imprint’s funds were later supplemented by a grant from Belknap’s mother.) And consider Piketty’s native France, where the scores of artists who relied on bequests or family support to further their careers included painters such as Corot, Delacroix, Courbet, Manet, Degas, Cézanne, Monet, and Toulouse-Lautrec and writers such as Baudelaire, Flaubert, Verlaine, and Proust, among others.

Notice, too, how many of those names hail from the nineteenth century. Piketty is sympathetically attached to a relatively low capital-to-income ratio. But the nineteenth century, with its high capital-to-income ratios, was in fact one of the most dynamic periods of European history. Stocks of wealth stimulated invention by liberating creators from the immediate demands of the marketplace and allowing them to explore their fancies, enriching generations to come.

But the Belle Époque (and its predecessor) has got nothing on the CIA.

The Central Intelligence Agency on Friday, April 11th posted to its public website nearly 100 declassified documents that detail the CIA’s role in publishing the first Russian-language edition of Doctor Zhivago after the book had been banned in the Soviet Union. The 1958 publication of Boris Pasternak’s iconic novel in Russian gave people within the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe the opportunity to read the book for the first time.

The declassified memos, letters, and cables reveal the rationale behind the Zhivago project and the intricacies of the effort to get the book into the hands of those living behind the Iron Curtain.

In a memo dated April 24, 1958 a senior CIA officer wrote: “We have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country [and] in his own language for his people to read.”

After working secretly to publish the Russian-language edition in the Netherlands, the CIA moved quickly to ensure that copies of Doctor Zhivago were available for distribution to Soviet visitors at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. By the end of the Fair, 355 copies of Doctor Zhivago had been surreptitiously handed out, and eventually thousands more were distributed throughout the Communist bloc.

As it happened, Pasternak went on to win the 1958 Nobel Prize for literature, the popularity of his novel skyrocketed, and the plight of the great Russian author in the Soviet Union received global media attention.

Subsequently, the CIA funded the publication of a miniature, lightweight paperback edition of Doctor Zhivago that could be easily mailed or concealed in a jacket pocket. Distribution of the miniature version began in April 1959.

These declassified documents about Doctor Zhivago are just the latest in a long line of revelations about how central the CIA was to the cultural and aesthetic life of the twentieth century. Was there a better patron of abstract expressionism—of Pollock, Rothko, De Kooning, at least on the global scale—than the CIA? And while the Saunders thesis of the cultural Cold War (the thesis long predates her, of course, but she helped popularize it after the Cold War) has its problems and its critics, the CIA did fund literary magazines like Encounter, even Partisan Review when it seemed like it was going to go belly up, international tours of symphony orchestras and jazz ensembles, and art exhibits around the world.

And while we’re on the topic of government patronage of the arts, let’s not forget the Bolsheviks, who managed, before the full onset of Stalinism and Socialist Realism, to fund, support, and inspire some pretty damn good avant-garde art. (And some not so good art: Ever since I learned that Ayn Rand developed some of her most enduring aesthetic tastes by attending, with the help of cheap tickets funded by the Bolsheviks, weekly performances of cheesy operettas at the Mikhailovsky state-run theater, I’ve held Lenin responsible for The Fountainhead.)

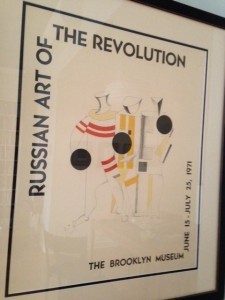

My most prized print is the poster of a 1971 exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum of “Russian Art of the Revolution.” It features El Lissitzky’s Sportsmen, which he did in 1923. (I managed to salvage it from the garbage after the office of a former colleague was cleaned out.) While eclipsed by the later exhibit at the Guggenheim, the Brooklyn Museum show was the first of its kind, I believe, in the States. In any event, it gives a good sense of what Soviet support for the arts achieved.

Cowen’s argument has a long history, but it’s not clear to me why he believes it’s dispositive. When it comes to funding for the arts, there’s more than one way to skin a cat.

April 25, 2014

Schooling in Capitalist America

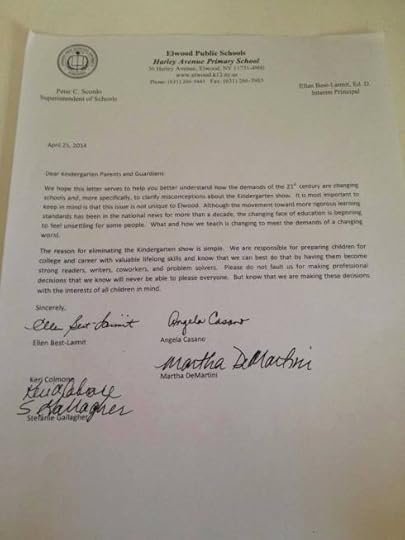

The following letter was sent to the parents and guardians of kindergarteners at the Harley Avenue Primary School in Elwood, which is in Suffolk County, New York. The letter explains that the school’s annual kindergarten show has been canceled. It is signed by the interim principal and several other individuals, at least some of whom are teachers. According to the organization that posted it on Facebook and Twitter, the letter’s authenticity has been confirmed by a parent in the school district. I also googled the names of the signatories, and several of them appear to be legitimate. (UPDATE: The letter’s authenticity has been definitely confirmed by The Washington Post.)

The letter reads as follows:

Dear Kindergarten parents and guardians:

We hope this letter serves to help you better understand how the demands of the 21st century are changing schools and, more specifically, to clarify misconceptions about the Kindergarten show. It is most important to keep in mind that this issue is not unique to Elwood. Although the movement toward more rigorous learning standards has been in the national news for more than a decade, the changing face of education is beginning to feel unsettling for some people. What and how we teach is changing to meet the demands of a changing world.

The reason for eliminating the Kindergarten show is simple. We are responsible for preparing children for college and career with valuable lifelong skills and know that we can best do that by having them become strong readers, writers, coworkers, and problem solvers. Please do not fault us for making professional decisions that we know will never be able to please everyone. But know that we are making these decisions with the interests of all children in mind.

Sincerely,

I have no idea what prompted this decision. I do know that thinking and talking about five-year-old boys and girls in this way—”We are responsible for preparing children for college and career with valuable lifelong skills and know that we can best do that by having them become strong readers, writers, coworkers, and problem solvers”—is the very definition of a sick society. This letter, as its signatories acknowledge, is just a symptom.

Update (1 am)

Just in case there’s any confusion, I want to be clear. I didn’t post this letter in order to attack the individuals who wrote or signed it. I have a tremendous amount of respect for teachers , as anyone who follows this blog knows. As I said above, I have no idea what prompted this decision or what particular constraints these teachers are facing. Knowing the kind of pressure the teachers of my own daughter, who’s also in kindergarten here in Brooklyn, are facing, I can well imagine these teachers not being able to reconcile the expectations of these new standards with the demands of organizing a kindergarten show. There are only so many hours in the day. As I said, this letter, and this decision, is just a symptom of a larger problem: school in capitalist America.

That said, the lead signatory on this letter is the school principal, who does have to accept some responsibility for this decision. Principals are supposed to lead, not merely follow. And rather than voice any discontent with the national developments, this letter affirms and owns those developments. That, it seems to me, is a problem.

How We Do Intellectual History at the New York Times

You see, says Sam Tanenhaus, it’s not just that Thomas Piketty may be right, or that he’s been doing this research for years, or even that he’s tapping into widespread concerns about inequality. No, it’s that every decade, America needs an icon of ideas, who embodies in her person (rather than her arguments), the dream life of the nation. In the 1960s, it was Susan Sontag. In the 1970s, it was Christopher Lasch. In the 1980s, it was Allan Bloom. In the 1990s, it was Francis Fukuyama (who wrote his essay in 1989, but decades will be decades). In the 2000s, it was Samantha Power. Yes, Robert Putnam was a “gifted thinker,” but remember the Rule of Decades: you can only have one every ten years. And, sure, Tanenhaus says you can have two or three, but you definitely can’t have two whose last names start with P. And Power has a “flowing red mane”—like Sontag had a flowing black mane, and then a flowing black mane with a silver streak—so she was the better choice. And now there’s Piketty. And he’s French, you see, which means he’s kind of like Sontag. And he’s good-looking like Sontag and Power. And he has hair too. And on Twitter they’re debating whether he’s hot or not. Which they would have done with Sontag back in the Sixties, but there was no Twitter then. And, oh shucks, let the man speak for himself:

All of which is to say that however original Mr. Piketty’s economic argument may be, he is the newest version of a familiar, if not exactly common specimen: the overnight intellectual sensation whose stardom reflects the fashions and feelings of the moment.

And that, my friends, is how we do intellectual history—no, sorry, “cultural studies” (they really use that phrase, right above the headline, which is “Hey, Big Thinker”; where is Dwight Macdonald when you need him?)—at the New York Times.

NYU: where Socratic dialogue is a Soviet-style four-hour oration from the Dear Leader

So the pro-Israel forces are in a tizzy again about a violation of campus propriety.

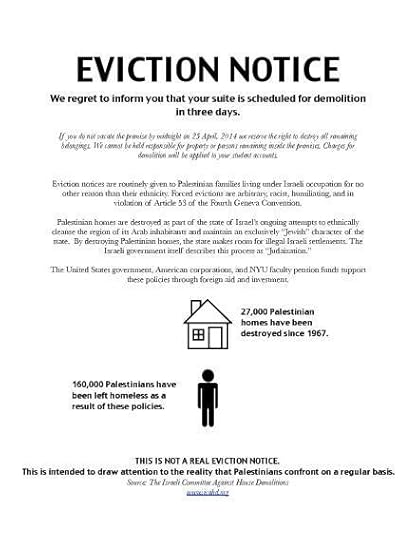

It seems that the Students for Justice in Palestine group at NYU distributed fliers across two dormitories informing the students that they had to evacuate their dorms because the buildings were going to be demolished within three days. The obvious point being to model what it feels like to be a Palestinian, who is routinely subjected to such notices. Which is exactly what the flier said. And just in case there was any confusion, the good folks at SJP took pains to write across the bottom of the flier:

THIS IS NOT A REAL EVICTION NOTICE. This is intended to draw attention to the reality that Palestinians confront an a regular basis.

Now pro-Israel students, groups, and politicians are claiming that the fliers are anti-Semitic and that they create a “hostile campus environment.” NYU has launched an investigation.

More hilarious, the university’s spokesman says that the fliers are “not an invitation to thoughtful, open discussion” and that they are “disappointingly inconsistent with standards we expect to prevail in a scholarly community.”

From the university where Socratic dialogue is a Soviet-style four-hour oration from the Dear Leader.

Outlook (5 pm)

For a much fuller and more comprehensive dissection of this “controversy,” see Phan Nguyen’s masterful take.

My Intro to American Government syllabus…

As God is my witness, I swear that before I die I will teach an Intro to American Government course in which the only text is Kitty Kelly’s biography of Nancy Reagan (an unheralded masterpiece, in my opinion). At some point in the semester, we’ll screen this documentary about Joan Rivers. And at the end of the semester, we’ll offer a libation to Michael Rogin.

April 24, 2014

On Writerly Historians

I’ve been reading a work of American history for the last few weeks, and it’s making me crazy. I really think history took a wrong turn when its practitioners decided to opt for narrative over analysis. Not because that’s a methodologically unsound choice—it’s not—but because most of the people who’ve made it are just not up to the job. You’ve got these self-styled writerly historians, writing stories that are larded with “the telling detail” that doesn’t tell you anything at all. It’s just page after page of chazerai. Guys, if you’re going to be a Writer, take this lesson from a guy who knew a thing or two about writing:

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

Update (April 25)

On Facebook, Josh Mason made a good observation: “The problem isn’t so much that most historians aren’t Balzac, as that they’ve chosen a form that you need to be Balzac to pull off.” Is that too much to ask?

Speaking on Clarence Thomas at the University of Washington

On Saturday, May 3, I’m going to be presenting a paper on Clarence Thomas at the University of Washington. It’s part of a conference on African-American Political Thought: Past and Present. The conference has an amazing line-up: Michael Dawson on Marcus Garvey, Nikhil Singh on Malcolm X, Cedric Johnson on Huey Newton, Lawrie Balfour on Toni Morrison, Melvin Rogers on David Walker, Naomi Murakawa on Ida B. Wells, and many more.

My paper is called “Smiling Faces Tell Lies: Pessimism, Originalism, and Capitalism in the Jurisprudence of Clarence Thomas.” Here’s the nut graf:

It’s not surprising that Clarence Thomas is black and conservative. From Burke to Ayn Rand, conservatism has been the work of outsiders and upstarts, hailing from the peripheries of the national experience. And black conservatism has an especially long, if unstoried, history in this country. Nor is it surprising that Thomas’s conservatism should draw from the Black Nationalist tradition. That confluence also has a long, if less unstoried, history in this country. What is surprising about Clarence Thomas is that he’s a Supreme Court justice who has married the bleakest vision of the black past to a document that is not only the fountainhead of that past but is also, on his account, the source of an alternative future—not, as Thurgood Marshall and other liberal constitutionalists would have it, because it is a “living Constitution,” but precisely because it is dead. That is indeed surprising, and worth puzzling over.

Come check it out. Details and schedule here.

April 23, 2014

On the death of Gabriel García Marquez

Greg Grandin writes in The Nation:

Born in 1927, Gabriel García Márquez was 87 when he died last week. According to his younger brother, Jaime, he had been suffering from complications caused by chemotherapy, which saved his life but accelerated his dementia, a disease that apparently ran in his family. He’d call his brother and ask to be reminded about simple things. “He has problems with his memory,” Jaime reported a few years back.

Remembering and forgetting are García Márquez’s great themes, so it would be easy to read meaning into his senility. The writer was fading into his own solitude, suffering the same fate he assigned to the inhabitants of his fictional town of Macondo, in his most famous novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude. Struck by an insomnia plague, “sinking irrevocably into the quicksand of forgetfulness,” they had to make signs telling themselves what to remember. “This is a cow. She must be milked.” “God exists.”

…

The climax of One Hundred Years of Solitude is famously based on a true historical event that took place shortly after García Márquez’s birth: in 1928, in the Magdalena banana zone on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, not far from where the author was born, the Colombian military opened fire on striking United Fruit Company plantation workers, killing an unknown number. In the novel, García Márquez uses this event to capture the profane fury of modern capital, so powerful it not only can dispossess land and command soldiers but control the weather. After the killing, the company’s US administrator, “Mr. Brown,” summons up an interminable whirlwind that washes away not only Macondo but any recollection of the massacre. The storm propels the reader forward toward the novel’s famous last line, where the last descendant of the Buendía family finds himself in a room reading a gypsy prophesy: everything he knew and loved would be “wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men…because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.”

It’s a powerful parable of imperialism. But the real wonder of the book is not the way it represented the past, including Colombia’s long history of violent civil war, but how it predicted the future.

One Hundred Years of Solitude first appeared in Spanish in Buenos Aires in May 1967, a moment when it was not at all clear that the forces of oblivion had the upper hand. That year, the Brazilian Paulo Freire, in exile in Chile and working with that country’s agrarian reform, published his first book, Education as the Practice of Freedom, which kicked off a revolution in pedagogy that shook Latin America’s top-down, learn-by-rote-memorization school system to its core. The armed and unarmed New Left, in Latin America and elsewhere, seemed to be in ascendance. In Chile, the Popular Unity coalition would soon elect Salvador Allende president. In Argentina, radical Peronists were on the march. Even in military-controlled Brazil, there was a thaw. Che in Bolivia still had a few months left.

In other words, the doom forecast in One Hundred Years was not at all foregone. But within just a few years of the novel’s publication, the tide, with Washington’s encouragement and Henry Kissinger’s blessing, turned. By the end of the 1970s, military regimes ruled the continent and Operation Condor was running a transnational assassination campaign. Then, in the 1980s in Central America, Washington would support genocide in Guatemala, death squads in El Salvador and homicidal “freedom fighters” in Nicaragua.

Political violence was not new to Latin America, but these counterinsurgent states executed a different kind of repression. The terror was aimed at eliminating not just opponents but also alternatives, targeting the kind of social-democratic solidarity and humanism that powered the postwar Latin American left. Hundreds of thousands of people were disappeared and an equal number tortured. Hundreds of communities were, like Macondo, wiped off the face of the earth.

It is this feverish, ideological repression, meant to instill collective amnesia, that García Márquez so uncannily anticipates in One Hundred Years. “There must have been three thousand of them,” says the novel’s lone survivor of the banana massacre, referring to the murdered strikers. “There haven’t been any dead here,” he’s told.

A year and a half after García Márquez published that dialogue, a witness to the October 2, 1968, Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City cried, “Look at the blood… there was a massacre here!” To which a soldier replied, “Oh lady, it is obvious that you don’t know what blood is.” Hundreds of student protesters were killed or wounded that day by the Mexican military, though for years the government denied the extent of the slaughter. Even the torrential downpour in One Hundred Years is replicated at Tlatelolco: as Mexican tanks rolled in to seal off the exit streets, one witness recalls that “the drizzle turned into a storm…and I thought that now we are not going to hear the shooting.”

…

As a young writer, García Márquez felt constrained by the two genre options available to him: either florid, overly symbolic modernism or quaint folklorism. But Gaitán offered an alternative. Upon hearing that speech, García Márquez “understood all at once that he had gone beyond the Spanish country and was inventing a lingua franca for everyone.” García Márquez describes the style as a distinctly Latin American vernacular that, by focusing on his country’s worsening repression and rural poverty, opened a “breach” in the arid discourse of liberalism, conservatism and even Marxism.

García Márquez flung himself through that breach, developing a voice that, when fully realized in One Hundred Years, took dependency theory (a social-science argument associated with the Latin American left that held that the prosperity of the First World depended on the impoverishment of the Third) and turned it into an art form.

…

If Castro is autumn’s patriarch, Allende is the democratic lost in history’s labyrinth. Drawing on his by then finely tuned sense of historical existentialism, García Márquez presents Allende as a fully realized Sartrean anti-hero, alone in the presidential palace, “aged, tense and full of gloomy premonitions.” The Chilean embodied and confronted an “irreversible dialectic”: Allende’s life proved that democracy and socialism were not only compatible but that the fulfillment of the former depended on the achievement of the latter. Over the course of his political career, he was able to work though democratic institutions to lessen the misery of a majority of Chileans, bringing them into the political system, which in turn made the system more inclusive and participatory. But his life, or, rather, his death, also proved the opposite: democracy and socialism were incompatible, because those who are threatened by socialism used democratic freedoms—subverting the press, corrupting opposition parties and unions, and inflaming the military—to destroy democracy.

Read it all here, at The Nation, and then make sure to buy Grandin’s latest book The Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World—the true story behind Melville’s Benito Cereno. That old cliché about truth being stranger than fiction? There’s a reason it’s a cliché…

April 22, 2014

Classical Liberalism ≠ Libertarianism, Vol. 2

Antoine Louis Claude Destutt de Tracy, A Treatise on Political Economy (1817):

The truly sterile class is that of the idle, who do nothing but live, nobly as it is termed, on the products of labours executed before their time, whether these products are realised in landed estates which they lease, that is to say which they hire to a labourer, or that they consist in money or effects which they lend for a premium, which is still a hireling.—These are the true drones of the hive…

…

Luxury, exaggerated and superfluous consumption, is therefore never good for any thing, economically speaking. It can only have an indirect utility. Which is by ruining the rich, to take from the hands of idle men those funds which, being distributed amongst those who labour, may enable them to economise, and thus form capitals in the industrious class.

Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1960):

There must be, in other words, a tolerance for the existence of a group of idle rich—idle not in the sense that they do nothing useful but in the sense that their aims are not entirely governed by considerations of material gain.

…

What today may seem extravagance or even waste, because it is enjoyed by the few and even undreamed of by the masses, is payment for the experimentation with a style of living that will eventually be available to many.

…

The importance of the private owner of substantial property, however, does not rest simply on the fact that his existence is an essential condition for the preservation of the structure of competitive enterprise. The man of independent means is an even more important figure in a free society when he is not occupied with using his capital in the pursuit of material gain but uses it in the service of aims which bring no material return. It is more in the support of aims which the mechanism of the market cannot adequately take care of than in preserving that market that the man of independent means has his indispensable role to play in any civilized society.

Tyler Cowen, “Capital Punishment” (2014):

Piketty fears the stasis and sluggishness of the rentier, but what might appear to be static blocks of wealth have done a great deal to boost dynamic productivity….Consider Piketty’s native France, where the scores of artists who relied on bequests or family support to further their careers included painters such as Corot, Delacroix, Courbet, Manet, Degas, Cézanne, Monet, and Toulouse-Lautrec and writers such as Baudelaire, Flaubert, Verlaine, and Proust, among others….The nineteenth century, with its high capital-to-income ratios, was in fact one of the most dynamic periods of European history. Stocks of wealth stimulated invention by liberating creators from the immediate demands of the marketplace and allowing them to explore their fancies, enriching generations to come.

For “Classical Liberalism ≠ Libertarianism, Vol. 1″, see here.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers