Jonathon Green's Blog

October 27, 2021

Still Struggling With Finding Love Online?

The best advice I can give you is that you should never get into a relationship thinking that it’s going to get you somewhere. That’s just not true. You should get into relationships because you like them and you’re attracted to them. I’m not a big fan of online dating. I think you can meet great people online, but I don’t think it’s a particularly efficient process. I prefer the real world. I’ve never been a fan of meeting people online and I don’t think I ever will be. The thing about hookup culture is that it’s not just about having sex. The hookup culture doesn’t really have much to do with sex. It’s more about being able to fulfill your desires when you want to, how you want to, with whoever you want to.

The best way to find love is to work on your confidence and social skills and to make sure you’re putting yourself out there and not closing yourself off to the possibility of meeting the love of your life. It’s important to know how to tell when a date is going well. It’s not always possible to tell, especially if you’re on a first date, but there are a few signs you can look for to see if a date is going well. Hooking up is a lot of fun, but if you’re not seeing a future with the person you’re hooking up with, a hookup can leave you trapped in an emotional limbo.

Find A Way To Have Great SexNo Strings Dating is a new dating app that matches up people who are looking for a casual relationship. It’s a curated community where men and women can meet up and have a no strings attached relationship for a fixed period of time. The app matches you with people who have the same intentions as you and who are looking for the same thing. Being a published author is important for your career because it helps people trust you and it helps you build a bigger audience, but it’s not the only way to build a following. You can also build a following by having a blog, social media accounts, or a podcast. The reason why people don’t commit after a hookup is because there’s no sense of commitment in the situation. After a hookup, there’s no risk because you’re not attached to the other person.

Fuck For Free?It’s a great way to meet someone you’re interested in. It’s a great way to meet someone new and exciting and can give you the opportunity to meet someone with whom you might not normally cross paths. When you’re dating online, don’t go into it thinking that you’re going to meet the love of your life. You might meet them, but that’s not what online dating is for. It’s for meeting new people and exploring new options. Instead of going for commitment-heavy hookups, try going for more casual encounters with people you’re not going to be in a relationship with. These can be a lot more fun and a lot less stressful because you’re not worrying about whether or not they’re going to text you back.

The post Still Struggling With Finding Love Online? appeared first on Flirt & Fling.

August 26, 2015

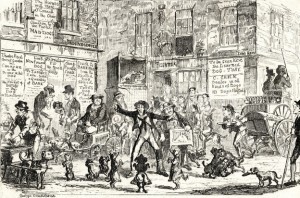

DOGGY DON’T

Ah, how we love them: movieland’s Lassie and Rinty, the Famous Five’s Timmy and the Outlaws’ Jumble, Tintin’s Snowy and Dorothy’s Toto, rancid Gaspode and prim Missis, noble Gelert and ever-attendant Bobby. Even Bullseye of Bill Sikes fame. See them rescue the hapless infant, see them adventure with plucky youngsters, see them savage innocent orphans, see them, yes it’s Bobby again, wait in vain. Woof-woof!

Slang, as ever, is less forgiving. The dog (see also mutt, cur, pooch and similar less than flattering synonyms) stands among the counter-language’s most well-used animals. But it’s like some linguistic version of vivisection: nary a pat, nary a stroke or kind word. These are not our best friends. Far from it. They poop, but we do not scoop. Bad dog!

And even by the standard of slang’s crowded pet shop (see cats and rats for instance), there are an awful lot of bad dogs on offer. If we include the phrases, compounds, derivatives and the rest of the linguistic mongrels that take their ancestry from the basic three letters, the word dog offers some 161 definitions. (And that’s not to mention those ‘dogs’ that are actually ‘gods’, as in such exclamations as dogdamn it! and dog blind me!, though who’s to say quite what’s happening with dog bite my ear! and as for dog my onions!. . .) It is impressive – not many words can mean (among so much else) a penis, an informer, miserliness and a cross-country bus – but it remains a grim picture.

Top, or should one say bottom of the bill is the earliest adoption: since the 16th century a dog has been an untrustworthy, treacherous, completely venal man and can be extended to women as well. William Dunbar, the early 16th century Scots poet, whose works give us the earliest recorded examples of some of the best-known obscenities, also offers in 1508 a less than appealing dog, who manages to incorporate a number of contemporary terrors, including sodomy and Islam: ‘Machomete, manesuorne, bugrist abhominabile, Devill, dampnit [damned] dog, sodymyte insatiable.’ Shakespeare, in Richard II, gives a clue as to just why the hapless canine has fallen so far from grace: ‘take heed of yonder dog: Look, when he fawns, he bites.’ Some say loyalty, the Bard, and slang, go for sucking up (and possibly back stabbing, or rather ‘biting’). That the word also referred to a horse that was difficult to handle does nothing to dilute the impact.

And while the cat is generally recognized as the ‘sexy’ beast, the dog gets its share. In one of slang’s cheerful paradoxes, the dog can mean both penis (which can of course be ‘stroked’) and vagina (also found around 1610 as a dog with a hole in its head.) Thus clapping the dog, stimulating a woman’s genitals with one’s fingers A dog can refer to a promiscuous man or woman and thence to a prostitute, especially the older and less appetizing of her sorority. Dog, bereft of any article, means sexual desire, thus doggish is lecherous or sexually obsessed. Though the randy dog may be unlucky with his own kind: the dog is also an unattractive woman.

Nor does the dog need to be a person. It can refer to something useless, worthless or broken down; a second-rate product or one that is hard to sell; a mediocre performance. It can signify unpleasantness, a bad characteristics, meanness, a disappointment, a failure and weakness or cowardice, typically in a boxer. (Used adjectivally, however, dog means cruelty or ruthlessness). And just to keep the negatives going, it can also mean ostentation or showiness, usually in the phrases put on dog, carry dog, do the dog, dog (up), pile or throw on dog. These all mean to show off, to put on airs; to do something energetically, noisily, although put on dog has a secondary meaning: to have sexual intercourse.

On with the beatings (not forgetting that to beat the dog means masturbate): The criminal world have always been ‘dog-lovers’ (and not merely of harnessed pit bulls). In all cases the slang stems from negative images: violence, disloyalty. The vicious dogs can represent any policeman – uniformed or plainclothes, but especially the more brutal of his species, a description that extends to prison officers. While we’re behind bars dog can also describe, in a woman’s prison, a girl who pursues (albeit only during her sentence) her fellow ‘bitches’, and in a male establishment, an older or tougher prisoner who exploits younger, weaker men as homosexual partners (such couples were also known as a jock and boxer but the reference is to underwear rather than species). As regards canine loyalty? Please. A dog, impressively one might suggest, can double as a pigeon (that variety that sits on the police station stool and ‘sings’). It is this type of dog that gives go or turn dog, defined variously as to become an informer, to inform on (one who is thus branded is on the dog); to become unkind (and treat someone cruelly); to let down, to ‘bite the hand that feeds you’, to be a coward and to betray and/or to take a bribe.

Dog offers a number combinations, none of them complimentary. the dog-booby (lit. a ‘male fool’) is a peasant or country bumpkin; dog breath is bad breath or one who has it; a dog-heart (for all that dogs are supposedly so brave) is a coward and a dog-driver, mocking him as one whose primary role is dog-catching, is a police officer. Dog-ass or dog-assed serves an all-purpose put-down. The dog days, in standard use referring to a period in which malignant influences prevail and a superstitious reference to the rising of the Dog Star, is found in slang as a synonym for the menstrual period. Perhaps the best known, if only historically now, is dogface. This US term started life in the late 19C to describe an unpleasant person, with its adjectival form dogfaced, stupid-looking and/or ugly. From there, in World War II it came to mean an infantryman, and was used as a calculated insult by disdainful members of the US Marine Corps, who scorn the gravel-pounders. A further possible link is the old Cheyenne War Society, founded during the Plains Wars, who called themselves Dog Soldiers.

So once it leaves the positive world of myths and legends, not to mention standard English, the dog’s negative role is quite unavoidable. Is there anything that can be rescued from the wreckage? Well, dog can, or rather could, be relatively neutral, just meaning a person, good or bad; it has meant a college freshman in the US; it has also meant a clever, cheery, hearty individual; especially in the affectionate phrase ‘you old dog’ or in the older concept a ‘jolly dog’. For Afro-Americans a dog has meant something or someone unusual or surprising, and more recently hip-hop has added more positive meanings: dog (also dawg and dogg) means a close friend and is often used as a term of address, usually man-to-man (‘Yo, dogg!‘). To be the dog (just like the man) is to be an admirable person. Raw dog, mercifully, is nothing to do with cooking: it’s sex without a condom.

To stick with the nouns there are yet still a number of other meanings. There is its abbreviation of hot dog, the spiced frankfurter slathered with mustard, popped in a bun and eaten by generations of pleasure-seekers. Standard English since around 1939, when it was served under that name by the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his guests, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the hot dog started life as slang. It probably comes from heavy-handed mid-19th century humour focusing on the supposed use of horse- and dog-meat as sausage filling, a concept that was accentuated by an 1843 scandal concerning the use of dog-meat for human consumption. The image was intensified by the use (c.1860) by German immigrants of Hundewurst, dog sausage, to mean smoked frankfurter sausages (larger sausages were Pferdwurst, ‘horse baloney’). The dachshund, of course, is a ‘sausage dog’. The modern term originated c.1895 at the Yale Club (as well as at Harvard, Cornell and other US ‘Ivy League’ colleges) where lunch wagons were known as ‘dog wagons’ and frankfurters known as ‘hot dogs’. Later cafes were dog joints, while the modern dog wagon refers to a small café or restaurant sited in a converted vehicle and to a van used for conveying prisoners. Linked, as it were, is dogcock, a modern N.Z. term that denotes any type of sausage. The filling of sausage meat is dog paste.

And the dog remains very versatile. It has been (in the Caribbean) a small copper or silver coin; for the early 19C underworld, and punning on the synonymous barker, it has been a pistol; it can be a state of drunkenness and the hangover that follows; to kill one’s dog means to get drunk (hence the invitation ‘let’s kill a dog’, after which, of course, comes the hair of the dog (that bit you). In Australia dog can also mean a drinking debt, while be on the dog list is to be barred from the pub. Australia also offers the dog license, since the 1940s a certificate of exemption from the prohibition of alcohol to Native Australians (under the Aborigines Protection Act 1909–43) that permits them to buy a drink in a hotel. Back in the UK, and back around 1600 (it was relaunched around 1850), dog-drunk is very drunk indeed. Still alcoholic, but quite separate, are the US terms dog, a pint bottle (470ml) of liquor and short dog, a half-pint bottle. Forty dog, a forty-ouncer, is a staple of hip-hop. In all cases the origin may lie in Yorkshire dialect dog, a small jug.

The rhyming dog and bone is a telephone while another rhyme, dog’s eye, is a meat pie and dog and cat means a mat; the shared initial gives a campus grade of ‘D’. while to never say dog (echoing the ‘dumb’ animal) is to remain silent. Back with humanity our canine can describe a tout (‘the salesman’s dog’) and a beggar who searches for cigarette or dog-ends. The ‘end’ imagery persists in the meaning of the hardest part of the job (once everything else is done all that is left is the ‘tail’) and the residue of poor-quality opium or heroin. A dog, though usually dogs, refers to the foot and with movement in mind the Dog puns on the transcontinental Greyhound bus.

And then there’s sex. Dog- or doggystyle (which not for nothing was the title of the rapper Snoop Dogg’s first hit CD), or dogwise, dog- or doggy fashion or even dog’s marriage, wherein the bitch is doubtless euphemized as a lady dog or dog’s wife. The rear-entry position. Not the dogpaddle, which is anal intercourse, just an image of dogs’ mating. (‘What are those two dogs doing, mummy?’ ‘Well, darling, the little one’s tired and the big one is helping by pushing her all the way home.’) Doggy sex gives a dog’s match, based the brevity of the intercourse and the lack of privacy of mating dogs, which is defined as sex in the open air, especially by the wayside and which gives to make a dog’s match of it, to have sex in the open air or to have a spontaneous quickie. It also gives dog-knotted, source of much crude humour, slang’s description of two lovers locked together during intercourse because of a vaginal muscle spasm brought on by a sudden shock. To play the dog is to display oneself sexually, a dog’s mouth is a tight vagina, and to stroke the dog is to caress it. To suggest that someone sucks a (big) dog’s dick is a phrase of extreme rudeness, while anything which does that kind of sucking is unpleasant or tedious. The last few decades have seen the arrival of dog’s latest sexual evolution and the 21st century’s take on the peeping Tom, dogging: first defined as spying on others having sex in public spaces, usually car parks. The term supposedly comes from the voyeur’s excuse as he sets off for a night’s pleasure: ‘I’m taking the dog for a walk’ although it probably just uses dog, to have sex, since dogging also covers those who provide the ‘live show.’

Finally a couple of late 18th century concepts: the dog’s rig (from rig, a romp) sexual intercourse taken to exhaustion, followed by mutual disinterest (no post-coital cuddles for the animals), and the dog’s portion, otherwise ‘a lick and a smell’ (Grose, 1785) in other words virtually nothing; especially when used of a man who pursues a woman and gets very little for his pains.

A variety of terms deal with unpleasant people, and ways of attacking them. Dog meat, dogpiss (also third-rate liquor), dogshit, dog turd, dogsucker (plus its adjective dogsucking), dogfucker and dog nuts all indicate an unpopular person although the last, echoing the synonymous mutt’s nuts, and indeed the equally congratulatory dog’s bollocks, can turn head-over-heels and mean someone or something excellent. Dog’s abuse is harsh verbal criticism and to dog-mouth is to offer it. A dog trick is a treacherous or spiteful act, an ill-turn or a mean, cruel trick. Dog’s bottom, oddly enough, is an affectionate term of address. To dog out can also mean to intimidate or criticize, but parallel meanings play on the verb’s various uses and include to keep a lookout; to approach sexually; to betray, to neglect, to treat with disrespect.

And there are more phrases, offering a wide range of meanings and all pinned to dog in one of it’s guises. To die like a dog (in a string) is to perish on the gallows; to get in(to) a dog corn-piece is to get into difficulties. Why? Because the dog here (i.e., the West Indies) is synonymous with a guard or watchman, and if he catches you in his corn-piece or corn-field you’re in trouble. (To be in trouble is also in the dogfuck, though dogfuck and its derivatives usually take us back to sex).That same watchman can keep dog, keep a lookout. Does the dog have a nose? Well, is the bear a Catholic? To have a dog tied up, with its image of having left one’s dog while moving on elsewhere means to be indebted, especially at a hotel. Let the dog see the rabbit is to give someone a chance to get on with a task while to lose one’s dog was to lose control of a situation.

Australia’s dog and goanna rules, the image of a fight between a dog and a goanna lizard is another way of saying no rules at all; a dog and pony show (or a horse and dog show) is any elaborately formal occasion, used for official briefings, public relations and so on. The original dog and pony shows were small circuses, where they were the sole animal performers; thus the image is of an event which boasts much presentation but little substance. The simple dog show, and the dog’s chance, both mean no chance at all. A dog-fight was a fistfight and is now any event considered coarse or vulgar. A dog in a doublet is a daring, bold person and recalls the German custom of dressing the dogs used to hunt wild boar in a form of buff-coloured doublet; it gives its own derivations: proud as a dog in a doublet, very proud and a mere dog in a doublet, a pitiful figure, one who shows off to no avail. When the dogs are barking one has a ‘hot tip’ on a racehorse in Australia, although it can also refer to painful feet in the US, and the comment the dogs have not dined once alerted someone whose shirt is hanging out. All the dogs in or on the street means all the world in Ireland and finally, from the world of US short-order cooking, dogs in the grass (or puppies in a haystack) meant frankfurters and sauerkraut.

This next phrase would surely seem irredeemably sexual: fuck the dog (and sell the pups), which offers such variants as feed, finger, fug, screw and even, as a last resort, walk the dog; the abbreviation f.t.d. also does the job. (Dog away one’s time is a more restrained alternative). Yet, as its definition bears out, it’s all a tease; no form of sex, let alone bestiality comes into the equation. The phrase means to idle, to waste time, to loaf on the job or to bungle or blunder. To walk one’s dog, however, is a euphemism, yet another of those phrases offered when wants ‘to be excused’. One then disposes of some dog water, urine, although in other contexts it refers to semen.

And sometimes a dog is just a dog, even if it finds itself for slang’s purposes in some unlikely company. Dog juice is rotgut liquor, i.e. only good enough for an animal or common dog. Dog’s soup was either rain or drinking water. Dog food is variously disgusting food, a bribe (paid to a policeman, the dog), or in gay use a soldier, viewed as a potential partner (and based on dogface); his seafaring equivalent is of course seafood. A further variety of dog food means heroin. Dog’s meat was originally anything considered worthless, e.g. a badly written book or a poorly executed painting. In apartheid South Africa it referred to a domestic worker, a metonymical extension of the cheap cuts of meat which were cooked for the servants’ meals and which were otherwise considered as good enough only for the dogs. Dog’s nose was a 19th century drink: beer warmed nearly to boiling, mixed with gin or wormwood (the basis of absinthe), sugar and ginger; an alternative version substitutes brandy for the wormwood. It could also refer to an alcoholic whose preferred tipple is whisky. Although the beer/wormwood mixture was hot, the term refers to the healthy animal’s nose, which like alcohol, is ‘cold and wet’. Like both dog and nose, the combination dog’s nose can also mean a paid informer who ‘sniffs things out’.

The dog nigger (which US black term is not so much racist as defiant) is a black person who rejects the second-class role offered by the dominant white society; such aggression means that amongst his black peers he can also be seen as a very unpleasant person. A dog-robber is a piece of military jargon: an officer’s servant, who gained his unflattering nickname from his post-mealtime habit of grabbing any edible left-overs from the mess tables before they could be tossed out to the dogs. It is also used by British officers to describe their off-duty tweed civvies. In the dogbox, like in the doghouse, means in trouble, but the original dogbox was a railway carriage without a corridor in which each compartment was sealed off from its fellows and presumably resembled a kennel. A smaller vehicle, a police car, is a dogcart. A dogpatch is a small town or hamlet, based on Dogpatch, the hillbilly settlement in which L’il Abner (1934–77) the syndicated cartoon strip by Al Capp, takes place. A dogtown is another out-of-the-way place, and comes from US theatrical slang ‘let’s try it on the dog’, i.e. take a show around the provinces before ‘bringing it in’, i.e. to New York. The old cant term dog buffer means a dog stealer (itself based on the older bufe, a dog, which may reflect the dog’s bark), while a dog-stiffener, in Australia, is a professional dingo-hunter: the ‘stiffening’ refers to his rendering the animal a stiff or corpse. The dog shelf is the floor, a dog collar a woman’s choker necklace (and of course the back-to-front clerical collar), a dogtag was originally an identification disk but in later drug use describes the junkie’s dream: a legitimate prescription for otherwise illegal narcotics (for a US dog to be legal it must have a labeled collar). Dog work designates tedious, menial labour while the dog hours are the late night/early morning shift. The dog-end, the last fraction of a cigarette does not, it seems, find its origins in anything canine: the more like root is in docked, i.e. cut short. However the tobacco of which it was once rolled, dog-leg, does represent nature via the twists in which the tobacco was sold, which resembled the animal’s limb. Dog music refers to the howls of an injured person (presumably this dog is the cowardly variety, a ‘real man’ grits his teeth); to dogpile is for a group of people to leap on a single individual and a dog’s paw is a US gang tattoo comprising a triangle of three dots, indicating gang membership. Finally, and perhaps most bizarre, is dog-salmon aristocracy, a late 19th century US term, based on the nouveaux riches of the fishing industry, those who thinks they are superior to their peers.

A small subset all use dog’s as their basis: a dog’s age is a very long time (though dogs are far from especially long-lived; maybe it’s that counting seven of their years to our one?); the dog’s dinner or breakfast is an awful mess, and can also be found as a chook’s breakfast, doggy’s dinner or pig’s breakfast. Done like a dog’s dinner means utterly crushed, but add a monosyllable and done up like a dog’s dinner suggests the extremes of sophisticated dress. Australia’s dog’s disease can be any one of a number of diseases – none of which actually effect dogs – such as ‘flu (also known as dog fever), measles and malaria, not to mention a hangover. The dog’s dram was an early 19th century description of the act of spitting in someone’s mouth and simultaneously hitting them on the back. (And why, exactly?).

Used as a verb dog falls into a number of groups. In senses of acting antagonistically dog can mean pursue, hunt down (often with sexual intent); to follow; thus dog on, to make someone follow someone else, and to stare or glance unpleasantly at. In senses of speech, usually negative, the word means to betray, to inform against (also as dog in); to nag, criticize, harass or mistreat; to abuse, curse, or despise; to pester or irritate; to cheat, to lie or to deceive; to taunt, to tease, to mock or to be rude and finally to insult someone in front of their friends. Inevitably there are sexual uses. To dog or do the dog means to have sex, although the inference is usually of doggy-style rear-entry. It can also mean to rape.

In senses of failure or inadequacy the verb can signify to act in a menial capacity; to idle and to shirk off work; and in those of parting it can mean to absent oneself from school; to break an appointment, to stand someone up and thence either to end a relationship or to abandon an old friend for a new one.

Other than these negatives the word has meant to steal, to get a grade D in an examination, to put out a cigarette, to do something fast, hard or well, to defeat, to tear at something in the manner of a dog and thus literally and figuratively to worry. It can work as an adverb too, meaning utterly or completely. Thus dog-poor, extremely poor, dog-sick (and sick as a dog) seriously sick and dog-foolish, very dumb. To dog-wallop is to beat comprehensively. Verbal uses of dog also include dog along, Canadian for manage or subsist, dog around, to idle, dog on, to treat badly or to attack behind someone’s back, and a couple of Caribbean terms: dog back, to swallow one’s pride in the hope of regaining a formerly positive relationship, and dog behind, to act in a servile manner, to toady to.

Finally the phrase dog it offers its own small subset. In gambling it means to act weakly, to be a loser, to lack winning spirit; it can mean to idle or shirk, to waste time or hang back, to dawdle or go slowly. In sexual contexts it refers to dancing provocatively, having sex ‘dog-fashion’, and making it clear that one’s looking for sex (in the case of a woman). Other uses include dressing up in one’s finery, working as an informer, adulterating drugs so as to make them dangerous, acting arrogantly, working as a gay male whore and, based on doghouse, a wagon, traveling on freight trains.

June 14, 2015

Argotopolis: The Map of London Slang

I am pleased to announce the launch of a new project Argotopolis: the Map of London Slang. This is the product of a collaboration with the artist Adam Dant, images of whose remarkable cartography, and much more, can be found here: http://bit.ly/1L8qJDM. Our map, which features a wide range of the slang that has been generated by London and its many social ‘tribes’, can be found here: http://bit.ly/1edEymQ or here: http://bit.ly/1Gw5Jne

May 29, 2015

Timeline Tumblr

All the Timelines of Slang can be found here: http://thetimelinesofslang.tumblr.com/

This is an on-going project, and new ones will be added as and when I make them.

The most recent timelines deal with Oaths: http://timeglider.com/timeline/1c4aeb6734c835c9

and

Terms of Dismissal (‘I don’t care’, ‘Go away’, ‘Nonsense!’ etc.): http://timeglider.com/timeline/1cd736a70de296e8

They will be added to the tumblr asap.

January 11, 2015

H.L. Mencken: Where is the Graveyard of Dead Gods?

The great Henry Louis Mencken, atheist, sceptic, critic and commentator wrote this in 1922, entitled Memorial Service. Other than the unfortunate use of ‘savage’ (but Mencken would have no more bowed to political correctness, had he encountered it, than to any other manifestation of the ‘booboisie’), and some references to then contemporary Americans, I am hard put to see a word out of place.

Where is the graveyard of dead gods? What lingering mourner waters their mounds? There was a time when Jupiter was the king of the gods, and any man who doubted his puissance was ipso facto a barbarian and an ignoramus. But where in all the world is there a man who worships Jupiter today? And who of Huitzilopochtli? In one year – and it is no more than five hundred years ago – 50,000 youths and maidens were slain in sacrifice to him. Today, if he is remembered at all, it is only by some vagrant savage in the depths of the Mexican forest. Huitzilopochtli, like many other gods, had no human father; his mother was a virtuous widow; he was born of an apparently innocent flirtation that she carried out with the sun. When he frowned, his father, the sun, stood still. When he roared with rage, earthquakes engulfed whole cities. When he thirsted he was watered with 10,000 gallons of human blood. But today Huitzilopochtli is as magnificently forgotten as Allen G. Thurman. Once the peer of Allah, Buddha and Wotan, he is now the peer of Richmond P. Hobson, Alton B. Parker, Adelina Patti, General Weyler and Tom Sharkey.

Speaking of Huitzilopochtli recalls his brother Tezcatilpoca. Tezcatilpoca was almost as powerful; he consumed 25,000 virgins a year. Lead me to his tomb: I would weep, and hang a couronne des perles. But who knows where it is? Or where the grave of Quitzalcoatl is? Or Xiehtecuthli? Or Centeotl, that sweet one? Or Tlazolteotl, the goddess of love? Of Mictlan? Or Xipe? Or all the host of Tzitzimitles? Where are their bones? Where is the willow on which they hung their harps? In what forlorn and unheard-of Hell do they await their resurrection morn? Who enjoys their residuary estates? Or that of Dis, whom Caesar found to be the chief god of the Celts? Of that of Tarves, the bull? Or that of Moccos, the pig? Or that of Epona, the mare? Or that of Mullo, the celestial jackass? There was a time when the Irish revered all these gods, but today even the drunkest Irishman laughs at them.

But they have company in oblivion: the Hell of dead gods is as crowded as the Presbyterian Hell for babies. Damona is there, and Esus, and Drunemeton, and Silvana, and Dervones, and Adsalluta, and Deva, and Belisima, and Uxellimus, and Borvo, and Grannos, and Mogons. All mighty gods in their day, worshipped by millions, full of demands and impositions, able to bind and loose – all gods of the first class. Men labored for generations to build vast temples to them – temples with stones as large as hay-wagons. The business of interpreting their whims occupied thousands of priests, bishops, archbishops. To doubt them was to die, usually at the stake. Armies took to the field to defend them against infidels; villages were burned, women and children butchered, cattle were driven off. Yet in the end they all withered and died, and today there is none so poor to do them reverence.

What has become of Sutekh, once the high god of the whole Nile Valley?

What has become of:

Resheph Baal

Anath Astarte

Ashtoreth Hadad

Nebo Dagon

Melek Yau

Ahijah Amon-Re

Isis Osiris

Ptah Molech?

All there were gods of the highest eminence. Many of them are mentioned with fear and trembling in the Old Testament. They ranked, five or six thousand years ago, with Yahweh Himself; the worst of them stood far higher than Thor. Yet they have all gone down the chute, and with them the following:

Arianrod Nuada Argetlam

Morrigu Tagd

Govannon Goibniu

Gunfled Odin

Dagda Ogma

Ogryvan Marzin

Dea Dia Mara

Iuno Lucina Diana of Ephesus

Saturn Robigus

Furrina Pluto

Cronos Vesta

Engurra Zer-panitu

Belus Merodach

Ubilulu Elum

U-dimmer-an-kia Marduk

U-sab-sib Nin

U-Mersi Persephone

Tammuz Istar

Venus Lagas

Beltis Nirig

Nusku En-Mersi

Aa Assur

Sin Beltu

Apsu Kuski-banda

Elali Nin-azu

Mami Qarradu

Zaraqu Ueras

Zagaga

Ask the rector to lend you any good book on comparative religion; you will find them all listed. They were gods of the highest dignity – gods of civilized peoples – worshipped and believed in by millions. All were omnipotent, omniscient and immortal.

And all are dead.

September 3, 2014

New Timeline

Just added a new slang timeline to the selection. This time it’s Mental Instability: http://bit.ly/WbzK7Q

September 6, 2013

Timeslines Continued

New Timelines for Sexual Intercourse added:

Intercourse pt 1: The Basics: http://bit.ly/18Htiop

Intercourse pt 2: Oral etc: http://bit.ly/13nceoQ

Intercourse pt 3: Orgasm, Fluids, etc: http://bit.ly/19ow4kt

August 18, 2013

Timelines

I am building a series of Timelines based on the database that underlies Green’s Dictionary of Slang.

These are the links to those currently available:

Penis: http://bit.ly/14hM1V4

Vagina: http://bit.ly/1257HXD

Drunk: http://bit.ly/1dfdrjm

Alcohol: http://bit.ly/1b4ANMW

Pubs and Bars: http://bit.ly/17C9Vwo

July 29, 2012

Dollops of Mud and Demonic Poetry

A talk given to the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester as part of a Conference to celbrate the Fiftieth Anniversary of the publication of A Clockwork Orange

The phrase queer as a clockwork orange, which means eccentric or bizarre, and can be applied sexually or otherwise, was sourced by Anthony Burgess to late World War II when, as a serving soldier, he heard it in the mess. I am quite willing to believe him: the phrase is cognate with similar slang similes such as queer as a coot, first ascribed to his acquaintance Julian McLaren Ross, queer as a three dollar bill, queer as duck soup, a coinage of the 1930s and oldest of all queer as Dick’s hatband, which seems as impenetrable a construct as Burgess’s borrowing and has been recorded in this sense since at least 1835 (meaning ‘below par, or ‘out of sorts’ it goes back a further half-century). As I say, I wish to believe, but…the problem is that we have no proof. Despite the resources of the Internet, and other than in scholarly articles that quote Burgess himself, the first recorded citation comes as late as 1977, in a glossary appended to a book designed to help policemen battle with the contemporary world.

First recorded that is, other than in the book itself, although the ‘queer as’ never appears, and the basic phrase, for which Burgess subsequently drew his own illustration, is used either as the title of the writer F. Alexander’s magnum opus or to describe Alex as rendered void and directionless by the Ludovico therapy.

This is frustrating, and I am incapable as a lexicographer to overlook it, but it is ultimately one more subtext in a book that is awash with subtexts. Scholars – here too I have no doubt – continue to elucidate them. Meanwhile the slang lexicographer, that shameless voyeur, eyes fixed firmly on the gutter and its denizens, takes his own view. If it is, as Burgess described our craft, somewhat ‘mixed and eccentric’ and even ‘quarrelsome’, then please forgive me. For me the book is dominated by the role of Nadsat, the teen slang that Burgess conjured forth for Alex and his peers. There is also a good deal of what, perhaps paradoxically, I would term ‘mainstream’ slang, though this, I would suggest, is somewhat overlooked. It is surely the slangiest of Burgess’ books but not just that: rarely in any work of literature does what I term the counter-language play so central a role.

I shall return to A Clockwork Orange in greater detail, but first I would like to say a few words about Burgess and slang.

I can think of no-one, especially among those whose skills as a linguist stemmed from phonology, so willing to take this subset of English so seriously. Burgess wrote about slang, was regularly quoted about it and of course created his own version for his best-known novel. He devotes a chapter to it in A Mouthful of Air and if that is rather more of a tour d’horizon than a linguistic analysis of the register – and greater linguists than he have faltered before that task – it remains an excellent overview, even if, naturally, he could only work with what then existed.

Yet I am not sure, if I am honest, quite how much he actually liked it. Or should I say approved of it. Central to all his comments on the topic was his identification of the register not simply with those at the bottom of the social ladder, which status was forgivable, but also those far down on the literate one, which was not. Slang, read one review, was something that ‘dribbled’; in another he wrote of a text marred by ‘slackness and slanginess.’

He definitely appreciated its innate rebelliousness, its role, as I have described it, as the language that says ‘No’ the language that embodies doubt. ‘The word “slang”, he noted, ‘suggests the slinging of odd stones or dollops of mud at the windows of the stately home of linguistic decorum.’ And he understood exactly where this bottom-up language comes from, acknowledging that ‘the downtrodden […] are the great creators of slang’ but elsewhere dismissed Black English, as spoken in the impoverished American ghettoes, as ‘a tongue of deprivation’ and sneered at those who ‘sentimentally drool over its alleged expressive virtues.’ I shudder to imagine what he would have made of the Ebonics controversy of the late 1990s when in California this variety of speech was advocated as an alternative to standard usage. In 1970 he noted that though ‘[slang was’] humanly irreverent, [it] tends to be inhumanly loveless. It lacks tenderness and compassion; its poetry has the effulgence of a soldier’s brass buttons.’ Perhaps his most generous assessment came in A Mouthful of Air when he typified it as ‘the home-made language of the ruled, not the rulers, the acted upon, the used, the used up. It is demonic poetry emerging in flashes of ironic insight.’

It also in A Mouthful of Air that he referred to it as ‘a pile of fossilised jokes and puns and ironies, tinselly gems dulled eventually by overmuch handling, but gleaming still when help up to the light.’ The phrase ‘fossilised jokes’ seems to have been taken wholesale from the subtitle of Eric Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English in which they are included alongside puns, colloquialisms, catch-phrases and vulgarisms. Whatever he thought about slang, he undoubtedly liked Partridge, the leading slang lexicographer of the 20th century. The men had met in 1965 during Burgess’s own attempt to compile a dictionary of contemporary slang.

He recalled in You’ve Had Your Time that

‘Eric Partridge had invited me [...] to cannibalise his own great dictionary to the limit, but I feared that I was not really a lexicographer. The lexicographer’s work is never done. He has more correspondence than the novelist, for people will go mad about words while ignoring literature. New words are born every day. New ingenuities of etymology from country vicarages and old people’s homes have to be rejected with courtesy. Still, I was tempted. The lexical bulk of any dictionary is to be found under ‘S’, but the true linguist thinks of ‘S’ as accommodating two different phonemes – the ‘s’ of ‘sit’ and the ‘sh’ of ‘shot’ – while the ‘B’ entries -initialising unequivocally with the ‘b’ phoneme – present the true superlative of weight. If I could get through ‘B’ without too much groaning I would take on the whole task.’

The true linguist indeed, but lexicographers play by other rules. For one so knowledgeable of dictionaries, it surprises me that he appeared to think one compiled them by starting at A and moving on to Z. If only. In the event he gave in after a stab at B and left the job to Partridge, the expert. They remained friends till the older man’s death in 1979 and Burgess wrote generously –perhaps over-generously – of the lexicographer in both reviews and in the posthumously issued Eric Partridge in his Own Words.

If Partridge has an over-riding fault, it is in his willingness to allow guesswork into his etymologies. The orthodox position is expressed by Oxford etymologist Anatoly Liberman, who has made it clear that ‘better no etymology at all than a bad etymology.’ As Partridge’s successor, and faced with the same problems as he was – since slang is particularly cussed when it comes to elucidating its roots – I have to agree, however much my teeth may be gritted as I say so. ‘Etymology unknown’ is the most depressing phrase I type, but type it I must because if that is indeed the case, then to offer readers anything else is inexcusable.

It interests me that the polymathic Burgess, whose knowledge of language was so extensive, and who, unlike many fulltime lexicographers, and especially those of us who focus on slang, had in addition at least a rudimentary knowledge of linguistics, was happy to echo his friend. Something, Partridge suggested, was always better than nothing, and Burgess backed him up. ‘I maintain,’ he says, ‘as Eric always did, that it is better to guess than to be silent.’ And adds, ‘This is amateurish, but it is human.’ The problem, I would suggest, is that if one is offering readers what is meant to be an authoritative work, a linguistic tool as I see the dictionary, then this is not merely amateurish, but downright misleading. I doubt that Burgess would have condoned, as do swathes of the internet where relativism rules and authority is condemned as ‘elitist’, the statement that fuck comes from the acronym ‘fornicate under command of the King’, and add a wholly specious anecdote as alleged proof, but such is the dangerous road on which Partridge and he were willing to tread. Of course Burgess was not a lexicographer, although he wrote appreciatively of such as Johnson and the OED’s James Murray, but a creative writer, a novelist. It is from this, I believe, that sprang what as a professional I see as a willingness to embrace guesswork. If one’s life is centred on invention, then why should etymologies, especially when they can play host to such alluring inventions, be excluded from one’s creative skills. Etymology, especially what I term deep etymology, taking words back to their very earliest roots and moving out from a simple meaning to the complex fusions that draw on a variety of linguistic sources, is a seedbed of potentiality. The necessity, however, is to root out weeds, and Burgess was too willing to let them flourish.

As he characterised Partridge, Anthony Burgess was himself over and above all ‘a lover of words’, a quite literal philologist, revelling in their complexity, their variety and their potential for manipulation. His own vocabulary, of course, was impressively wide-ranging. The briefest glance at some reviews offers hogo, mantrip, protonym and malefit: hardly standard and there is much more.

He is a devotee of the dictionary, trusting the lexicographers and admiring their scholarly, disciplined, hard-won creations. I can think of few, if any outside the professionals – and perhaps including them – who write of lexicography and its practitioners with such sympathy and understanding. He had taken against Marghanita Laski, and mocked her in the street name Marghanita Boulevard in A Clockwork Orange; he might have been mollified had he known that she was the chief contributor of citations to the second edition of the OED. As he puts it in a review of Katherine Murray’s biography of her grandfather Sir James, ‘There are naïve people who regard philologists as dull, forgetting that the rogue-god Mercury presides over language.’ Elsewhere he noted that ‘The study of language may beget madness. Mercury presides over philology as well as thievery.’ He was very happy to pay Mercury his due.

With all of that in mind, I cannot imagine, therefore, that Burgess disliked slang. I cannot imagine that he disliked any language. He did, however, or so it seems to me, distrust it. He admired and even indulged Partridge, wrote on his slang lexicography and that of others, but in the essays and reviews that I have read, I haven’t found a parallel admiration for the lexis with which Partridge worked. He is interested, knowledgeable (though not invariably accurate) but he lacks respect. This sense of distrust seems equally born out in the work in which, of course, slang plays its greatest role: A Clockwork Orange. Though even, or perhaps I should say especially here, Burgess’s take on the counter-language, was such that – dissatisfied with the potential ephemerality of what was on offer – he chose not to use the youth slang that was available, but to invent his own and in so doing to use as his primary source not English, but a language that we can assume would have been even more alien than contemporary youth-speak to all but a minority of his readers

The genesis of A Clockwork Orange can be found, as Andrew Biswell has explained, in spring 1961 when Burgess wrote to his friends Diana and Meir Gillon that

‘I am in the early stages of a novel about juvenile delinquents in the future’ and noted in parenthesis that ‘I’m fabricating with difficulty a teenage dialect compounded equally of American and Russian roots’.

The American contribution would fade, replaced by mainstream British slang or plays upon it, but the Russian element, as we know, continued to take the dominant role.

I am hardly alone in paying Nadsat its dues, but before I consider the language there is another aspect that I would suggest makes itself particularly plain to one who researches, as do I, in writing’s less salubrious themes. Alex and his droogs, what might now be termed his crew or fam, his fellow gang-bangers (in the original and the more recent senses of that term) represent what by 1962 was a very well-established tradition: the J.D. or juvenile delinquent novel. I am not suggesting that Burgess had immersed himself in the work of ‘Hal Ellson’ (later the sci-fi author Harlan Ellison), or that of Wenzell Brown, Edward de Roo and ‘Vin Packer’ (actually Maryjane Meaker), even if their publisher Ace Books also gave readers Junkie, by Burgess’ acquaintance William Burroughs. But the world of the J.D. gangs, with their switchblades and leather jackets, their jailbait and gang rapes, their drugs and of course their slang, had proved very popular (it remains so, updated to the worlds of Irvine Welsh or Niall Griffiths) and one can see many of the same tropes in A Clockwork Orange.

This is not to say that A Clockwork Orange would have sat comfortably among such titles as Ellson’s Reefer Boy, Brown’s Jailbait Jungle or Packer’s Young and Violent, but those creations, set in 1950s New York, were not that far away either in time or in their violence, their hedonism and their disdain for convention. Some even included the obligatory trip to jail, wherein the hero experienced some form of reformation, though under less melodramatic circumstances than those suffered by Alex.

And there was, of course, their impenetrable slang. Burgess made a conscious decision to invent a slang for his near-future delinquents, and mixed it so heavily with Russian, it proved hard going for many readers. But in 1953 how many outside the initiates would have picked up ‘They bought some junk from a cat in the park, but it was real beat stuff and they didn’t get no charge’ or the exchange ‘The trim’s not bad. Let’s pull a midnight review.’ ‘Cut it,’ Thomas ordered. ‘We ain’t got no time to cat around.’ – both lines from Wenzell Brown novels. The young, as Burgess pointed out, have a language all of their own.

The juvenile delinquency considered in A Clockwork Orange is projected somewhere into the future and situated in an unspecified country where at least a proportion of the young seem to be running riot, and are waging war, with the aggressive collusion of the authorities’ front line agents, the police, on the established order. The future does not improve it. Anthony Burgess, whatever many viewers of the Kubrick film of his novel may have assumed, was not a fan of what the Fifties had coined as ‘youth culture’. It is informative briefly to compare his novel with another youth-focussed work, Colin Macinnes’ Absolute Beginners, published in 1961, while Burgess was still at work. Quite unlike Burgess, Macinnes aimed to celebrate youth. He loved their music, their clothes, what he believed was their lack of racism – other at least than in the Teddy Boys, positioned as the villains of the piece and as such a group who had wilfully failed to keep pace with developments – and above all their sheer modernity. He also attempted to display their language. Absolute Beginners, set very much in the here and now, sited in a Notting Hill that was still equated with blacks and bohemia rather than with bankers and bonuses, is resolutely upbeat. There are no killjoy authorities, let alone sadistic aversion therapists. If one fails to embrace youth, one has only oneself to blame. Even with a climatic chapter staged against the background of 1959’s Notting Dale race riots, it offers what can be called an optimistic ending.

The anonymous Absolute Beginner is portrayed as streetwise but he would not have lasted long one-on-one, let alone twenty-to-one with Alex. MacInnes had written affectionately of Tommy Steele; in a movie he might have cast Cliff Richard as his hero. Kubrick, of course, would use Malcolm McDowell, the gun-toting, vodka-swigging antihero of If. And his slang, while of its time, was predictable; Nadsat would have eluded him.

Burgess never mentions MacInnes; nor does he mention another contemporary ‘youth novel’, Robin Cook’s The Crust on Its Uppers, published like his own in 1962. This story, fictionalising that louche world where, to paraphrase, the Chelsea Set met the Kray Brothers, was another book where young protagonists were delineated by their own language. Cook used over 250 slang terms and provided readers with a glossary. Most were current, mainly from the East End, though few readers would have known them, and one, morrie, meaning a wide-boy, was definitely all Cook’s own. But one word hardly makes a lexis. MacInnes’ Beginners and Cook’s morries were of their own time. Burgess’ droogs were something else.

I hold no brief for analysing any aspect of Burgess’ novel other than in terms of the language. I am fortunate in the centrality of that language’s role and the fact that it is especially his invented tongue Nadsat, the language of his teenage hoodlums, that has made and kept it famous. Burgess’ aim, it appears, was to avoid linking his story to any time or place. He drew on his experiences of Teddy Boys in England and stilyagi on a visit to Leningrad, and brought in his wife’s assault, perhaps rape by a pair of GIs, but this was background. He did assemble a possible glossary, based on contemporary teen slang, but abandoned it.

As he explained in You’ve Had Your Time,

‘It was pointless to write the book in the slang of the early Sixties: it was ephemeral like all slang and might have a lavender smell by the time the manuscript got to the printers. It seemed, at the time, an insoluble problem. A slang for the 1970s would have to be invented, but I shrank from making it arbitrary.’ The solution came when he started, coincidentally, to relearn Russian ‘It flashed upon me that I had found a solution to the stylistic problems of A Clockwork Orange. The vocabulary of my space-age hooligans could be a mixture of Russian and demotic English, seasoned with rhyming slang and the gipsy’s bolo. The Russian suffix for –teen was nadsat and that would be the name of the teenage dialect.’

Recent editions of the book have been supplied with glossaries, and a canonical version thereof – based on that compiled by Stanley Edgar Heyman in 1963 – is widely available on the Internet. Burgess was unimpressed; he termed the glossary ‘stupid.’

Stupid or not, it was not available in the original editions. Readers were forced to use context as an aid to translation, although Alex, occasionally styling himself ‘Your Humble Narrator,’ is generous with his bracketed explanations of many terms. Some critics have suggested that the author was consciously and generously self-censoring, rendering the extremes of violence, of tolchocking, the britva and the old in-and-out, less immediately accessible and thus sparing the readers until, better accustomed to the atmosphere of this strange future world, they could more easily take them on board. There is nothing from Burgess to render this theory fact. What he does, with consummate skill, is to take a language that he, but one imagines relatively few of his readers knew: Russian, and by using both literal and ludic, usually punning translations, create an argot – a private language or jargon – for his gang of psychotic droogs. That its name, Nadsat, plays on the suffix used for the numbers thirteen to nineteen, but is used for teen as in teenager, underlines the way in which this was done. This playful redefining of Russian works throughout to sidestep the ties of contemporary youth slang. At the same time, readers who ‘got’ the puns, would have seen that Burgess still recognised what his teen contemporaries might have been saying. Kopat (to dig with a shovel) is used as ‘dig’ in the sense of enjoy or understand; koshka (cat) and ptitsa (bird) become the beatniks’ ‘cat’ and ‘chick’, although slang’s bird had already meant a girl since 1550. Burgess can also play with non-teen slang, such as his use of vareet (to cook up) which he uses in its non-culinary sense, meaning to prepare or make happen.

What Burgess did not use – I have no idea whether or not he knew its lexis – was mat, Russia’s purpose-built, centuries-old obscene slang. Had he done so he might have offered some form of play on mudi, for testicles rather than yarbles, from yarblicka, apples (though apples has been thus used in English slang) and a variation on the insult pedik or pidor, literally pederast, in place of sod. Lubbilubbing, from Russian lyublyu, love, would also have found a number of grosser synonyms.

Dr Brodsky, architect of Alex’s enforced reformation, terms Nadsat ‘the dialect of the tribe’ and dismisses it as ‘quaint.’ His sidekick, Dr. Branom sees it as a mongrel assemblage: ‘Odd bits of old rhyming slang […] A bit of gipsy talk, too. But most of the roots are Slav.’ And he attributes them to ‘Propaganda. Subliminal penetration.’

Dr Branom is right as regards the Slavic input – of the 242 terms included in the Heyman glossary some 190 have Russian origins, but otherwise he is overly glib. Those terms he identifies as rhyming slang do indeed rhyme, but with the exception of Charlie, a semi-rhyme based on Charlie Chaplin and as such more of a pun, which is first found in the US Army in 1917 but just once since, only for Burgess. Luscious glory, used for hair, may rhyme with upper or top storey, but that, in non-rhyming slang, usually means the head, cognate with the attic or that belfry in which one may encounter bats. Hound-and-horny, corny, exists nowhere but in the novel; pretty polly does indeed rhyme with lolly, money, and the phrase jolly for polly, sexually available for a price, is recoded in a gay lexicon of 1972. But not before and I would suggest that the phrase is primarily dependent on assonance. Ironically the one term that has resisted translation – though context makes it clear that sharp means a female – is perhaps the single genuine piece of rhyming slang. It abbreviates sharp and blunt, and means cunt, specifically the vagina and generically women.

As for Gypsy, or properly Romani, it is also less well represented than Branom suggests. The only term that Hayman claims is dook, ghost, which he links either to dook, a Romani term for magic (properly ‘second sight’) or to the Russian dukh: a spirit or ghost. Slang’s more usual use of the Romani is in dukkering, palm-reading, which is also linked to duke, the hand. Again, the gypsy terms come in what Hayman has missed. Cutter, used for money, comes from Romani couta, a guinea, and was long established in mainstream slang to mean cash. Rozz, which is used for policeman and is attributed to the Russian rozha, an ugly face or a grimace is surely no more than the English rozzer, which is considered to come from Romani roozlo, meaning strong and also used to mean a villain; I should add the alternative etymology: French argot’s rouse or roussin, a policeman, from roussin, medieval French for a warhorse or hunter.

What has tended to go relatively un-noticed, amid the fascination with Nadsat and the readers’ admiration of Burgess’ linguistic skills, is his use of English slang. Elsewhere, I would suggest, he is not an especially slangy writer. There are passages in Enderby and the Malayan books (where the appearance of banchoad, motherfucker, must have made knowledgeable readers jump), but he was not someone I turned to when looking for cite-dense texts. It was true that a few Nadsat terms were adopted after the movie was released, but such use was a fad; there is no evidence that it persisted.

In A Clockwork Orange Alex uses mainstream slang, though he weaves it around his Nadsdat vocabulary; so too do working class characters, typically policeman and prison warders. These do not, it appears, know Nadsat, or if they understand it they do not choose to use it. The authorities – the minister, the prison’s governor and charlie, and the two aversion therapists, remain limited to standard English. This is not to suggest that such slang is intended to create sympathy. Burgess’ use is accurate, but he is not placing it in the mouths of characters we are supposed to like. There may be a form of rhyming slang but there are no chirpy cockney sparrers. The warders and policemen, whether former droogs or otherwise, are violent; Alex and Co. need no introduction. Each side is pitted against the other and while the droogs may assume that Nadsat will be understood within their own circles, they know that more mainstream slang works better with the Establishment’s agents. The slang terms, like the Nadsat ones, showcase the themes that have always underpinned the counter-language: sex, violence and intoxication.

Having substituted Nadsat for real teen slang, Burgess’ mainstream lexis is very traditional. One finds done in, fagged and shagged (all exhausted), stinking, blast you, bastards, so (as an intensifier), like (as a modifier), crappy, not too clever, sing (to confess), bash in the chops, shop (as in ‘belong to the other shop’), meth (i.e. methylated spirits, not methedrine), rod, (the penis), crack into (to hit), lip music (talk), turnip (the head), bleeding, hole (the mouth as in ‘shut your hole’), cop it lucky, sod, sodding and try it (on). Sarky, sarcastic, shive, to cut (from shiv, a knife, another Romani term), and snuff it, to die are equally well established. Snoutie and tick-tocker appear to be inventions, but they have not travelled far from their origins, snout, jail slang for tobacco, and ticker, the heart. Pan-handle, for an erection, is new, but cognate with slang’s mast, prong, rail, truncheon and wood and underlines how well Burgess recognised the thematic synonymy that lies behind the slang lexis.

Certain terms occupy a zone somewhere between invention and the conventional. Cancer, a cigarette, simply abbreviates cancer stick; chai, while taken from Russian chai, meaning tea, could equally well have come from cha, long used in the British Army and beyond; glazz, an eye, also linked to Russian, might have relied on the synonymous glasier, used since the 16th century. Oozy, a bike-chain claims Russian uzh, a snake but one should note a semantic link to Dutch slang, which means both snake and chain. It is suggested that sammy, generous, comes from Russian: samoye, the most but I would opt for the mid-19th century stand sam (or sammy), to treat.

Cursing like a Bargee & Slinging the Bat

A paper on ‘Rudyard Kipling and Slang’ delivered to the Rudyard Kipling Society in London on June 29 2012

Rudyard Kipling is not at first sight a particularly ‘slangy’ author. If, as many of us do, we come to him as children he seems positively disapproving. In the Just so Story ‘How the First Letter Was Written he (as Tegumai) admonishes Taffy (his daughter Josephine) for using ‘awful’ to mean ‘great’. ‘Taffy,’ said Tegumai, ‘how often have I told you not to use slang? “Awful” isn’t a pretty word.”.’ Whether or not an adjectival use of ‘awful’ still qualified as slang in 1902 is arguable, and whether Kipling was appeasing those who termed his work vulgar, no matter. The reality is that when one starts dissecting Kipling’s fiction one finds that slang plays a regular, important role. There are hundreds of slang words and phrases in the works, as well as a wide range of job-specific jargon, typically in his sea stories. He uses it for the most basic of reasons: to confer authenticity. He is not a coiner, but a recorder, and his slang lexis is that of the contemporary world, leavened, as in the conversations of the Soldiers Three, by the specifics of a given background.

His areas of interest – schoolboys, soldiers – are of course two of the prime founts of all slang creation. He only missed out on criminals. But substitutes for them the jargons of various specialists, such as engineers, sailors and freemasons. However these are not general slang and I shall resist them.

If he does not immediately strike one as slangy today, his contemporaries were in no doubt, nor invariably complimentary. Critics used the word to denigrate; the pious burghers of Chicago attempted to boycott his work. The Nobel Prize committee of 1907 was undeterred: ‘The accusation has occasionally been made […] that his language is at times somewhat coarse and that his use of soldier’s slang […] verges on the vulgar. Though there may be some truth in such remarks, their importance is offset by the invigorating directness and ethical stimulus of Kipling’s style.’

Researching the citations that underpin the entries in my own slang dictionary, published in 2010, I naturally included Kipling on my reading list. He was not among those books that I first plucked from my shelves – Jack Kerouac, Raymond Chandler, Irvine Welsh – where every page seemed to offer multiple examples. But I could not have overlooked him. His works render up around 500 slang terms. This is an imprecise science – what I record is not always the entirety of what I find, since I require but a single example per definition per decade of use and if I have what I want, I do not duplicate – but it is a workable figure. Among literary stars Joyce is good for 1000 terms; Jane Austen for two. Kipling sits squarely in the middle. Of these almost 20 per cent represent, at least as currently recorded, the first uses of given terms. Among them are brass hat, an officer, conk out, to collapse, clobber, to hit, it, sex appeal, jammy, easy, leatherneck, a marine, mafeesh! the Arabic expression of dismissal and disinterest, rot, to talk nonsense, show, a battle, turf out, to eject and whack up, to accelerate. Most of them have lasted.

The sources of Kipling’s slang fall into three major groups: the language of Anglo-India, which in itself comprises English-Indian pidgin, Army usage and general slang; the schoolboy vocabulary of Stalky and Co, and the deviation into Cockney represented by Kipling’s venture into East End realism, ‘The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot.’ Ortheris is of course Cockney too, but as we shall see, more in style than in linguistic substance. Aside from those comes the general occurrences of slang to be found throughout the short stories. ‘The Story of the Gadsbys,’ that ‘tale without a plot’, is especially fruitful.

Notswithstanding Mrs Hauksbee, so much of Kipling’s world, as critics seem united in suggesting, represents male enclaves. Soldiers, schoolboys, subalterns and beyond them the experts in various male pursuits: engineering or deep-sea fishing. Badalia is a woman, but what greater example of male dominance does one require than her murder by a drunken, violent, and seemingly conscienceless husband. All of which makes this world the ideal repository for slang, the epitome of man-made language. Slang’s taxonomy: crime, intoxication, sex both private and commercial, insults personal, national and racial, a lexis of term for women that at the very best poses them as sex objects; one for men that tends to the self-aggrandizing. The abstract, the emotional, what one might term feminine language is quite absent. One might even go further and suggest that in the slang-rich tales, at least, there is even a sense if not of war then of focused antagonism, of pitting the individual or the group against some form of authority, be it the British Army, a public school, however anomalous a version, or even, in Badalia’s case, poverty. And the experts, for instance the fishermen, are battling nature itself.

That said, one must acknowledge a paradox. Kipling is infinitely complex but it is not wholly foolish to suggest that among his mottos was ‘do as you are told’ and another ‘know your place’. ‘Law Order Duty, Restraint Obedience Discipline’ as ‘McAndrew’s Hymn’ lists it. Slang is the antithesis: the language, as I have often defined it, ‘that says “no”’, a vocabulary which if it does boast a single abstract thought, it is that of doubt: a steadfast and mocking refusal to believe not simply in ‘higher’ things but that ‘high’ of itself is anything beyond a self-deluding, self-serving construct. Kipling uses it, but he does not, as it were, take its side.

In one of the first collections of slang, or more properly the canting speech of wandering criminal beggars, Thomas Harman’s Caveat for Common Cursetours of 1565, the author embellishes his lists and descriptions with a supposed conversation between a pair of rogues. It is a format that has been enshrined in slang writing – both lexicographical and fictional – ever since. It has been suggested that this exposure of a group’s language is an example of middle-class authority: by appropriating the language one displays one’s own power over its users. This, I think, complains too much. The appropriation, the display exists, but the back story seems simpler and less sinister. Like the lexicographers who collect it, the novelist is not usually a professional criminal, a pimp, a thug, or any other of those for whom slang is a lingua franca. But if the dictionary makers need to capture as much as possible to display their expertise and thus underpin the authority of their lexicons, then so too must the novelists to parade theirs, and in doing so confer that vital ingredient – authenticity – on their tale. Kipling is no exception. His skill is in the blending. Kipling learned up his slang as had Dickens, – typically the language of Fagin, Sykes and the gang – and duly exhibited it. Where Dickens scores over a potboiler such as his contemporary Harrison Ainsworth, is that the terms appear seamlessly. Kipling achieves this too. We know that this is a learned vocabulary – we know that Kipling did his homework – but it does not stand out as such. Mulvaney’s Irish may get perilously close to the stage at times, but it remains of a piece with the story; Stalky and Co may delve rather more deeply into Surtees and other literary sources than comparable schoolboys, but again it works.

So I am impressed by Kipling’s integration of slang into the work but perhaps not overwhelmed. It has been suggested that he ‘gave a voice back to the inarticulate’. No. He simply continued a long tradition. He was hardly the first to vocalize the Cockney, the question is simply did he, as has been claimed, do it in a novel, more truly representative way? Less debatable is his pioneering treatment of soldiers. At least the ‘other ranks’. Shakespeare, in Henry V, had offered his footsloggers, but his successors had stayed with the officer class. Kipling deals with officers, whether in embryo – Stalky’s ‘Coll.’ was after all a manufactory thereof – or in adulthood, but the first are schoolboys and the second are not delineated by their language, other than that its standard English tones underline their class. Soldiers Three has a very different perspective, and it is there that we can start.

Slang, as a linguistic phenomenon, was hardly new when in 1890 Kipling arrived in London. That same year saw the first – of seven – volumes of slang’s equivalent to Oxford’s work-in-progress, the New English Dictionary. This was Slang and Its Analogues, compiled by the scholar and spiritualist John S. Farmer, and Kipling’s friend-to-be W.E. Henley. This was serious scholarship but that it was impossible to get the book printed or publicly distributed in the UK reflected slang’s continuing outsider status. The book was still contentious 50 years on, when a writer described it as containing ‘over a hundred synonyms for the most ill-used monosyllable in the language, and none fit for decent print.’ I assure you, knowing the book well, that 100 is a gross understatement.

Kipling, meanwhile, was that year’s critics’ darling, feted by nearly all as the writer of Plain Tales from the Hills, Departmental Ditties, Barrack Room Ballads (published by Henley’s Scots Observer) and perhaps most important of all at that stage, the stories that made up Soldiers Three. They noted many things that rendered the young man’s skills outstanding, among them was his employment of non-standard language.

Yet there are not so many slang terms in Soldiers Three as one might expect: just over 40, and nearly all are spoken by an Irishman. And for all that Kipling was credited with their invention, the reality is that all were to some extent established. Kipling did not claim otherwise. What he did resent was the suggestion that he had made up the style, if not the substance, of his barrack-room badinage.

‘Among Mr. Kipling’s discoveries of new kinds of characters,’ said his fan, the poet and critic Andrew Lang, ‘probably the most popular is his invention of the British soldier in India.’ Kipling was less grateful than Lang might have expected. A letter of 1890 states how ‘the long-haired literati of the Savile Club are swearing that I “invented” my soldier talk in Soldiers Three. Seeing that not one of these critters has been within earshot of a barrack, I am naturally wrath.’ Kipling had not invented it. He had picked it up, along with the prototypes of his characters in such oases of ex-patriate tedium as the barracks at Mian Mar where as a journalist he had enjoyed relatively privileged access.

Barrack Room Ballads, with 57 terms, and Departmental Ditties, with 25, also offer up their share of slang. The first draws on the life of the other ranks with language to suit. Terms that had yet to be recorded include: sling the bat (to talk Hindi or Urdu; he had already introduced bat in Plain Tales from the Hills), blind (to swear and in its adverbial use, e.g. go it blind), clobber (as clob, to beat or kill), crack on (to boast), Fuzzy-Wuzzy (a Sudanese), grouse (to grumble), hairy (first-rate), hell for leather, jildi (speed, energy), give the knock (to knock down), oont (a camel), go on the shout (to go drinking) and snig (to pilfer). The Ditties, with their in-jokes and poèmes a clef stories of such as Potiphar Gubbins, C.E., Ahasuerus Jenkins and Delilah, are not based on soldiers’ lives: masher, skittles! (nonsense!), fanti (eccentric) and screw (a salary) are examples of that relatively exotic species: middle-class slang.

Kipling’s language, irrespective of coiner, came through him to exemplify a type. As Mafia dons and ‘soldiers’ began modelling themselves on the Godfather trilogy, Goodfellas and similar movies, so did the British trooper take on Kipling’s fictions as his model. In 1917 Sir George Younghusband recalled in A Soldier’s Memories, ‘I myself had served for many years with soldiers, but had never heard the words or expressions that Rudyard Kipling’s soldiers used [...] But sure enough, a few years after, the soldiers thought, and talked, and expressed themselves exactly like Rudyard Kipling had taught them in his stories [...] Kipling made the modern soldier.’ Younghusband was almost certainly over-doing it: it was highly unlikely that an officer would have been party to the language of those he commanded, but Kipling undoubtedly promoted rank-and-file language as no-one had attempted before him.

By the 1940s Orwell was offering a more skeptical assessment. For him the writer was patronizing and ‘facetious’: ‘The private soldier, though lovable and romantic, has to be a comic. […] Very often the result is as embarrassing as the humorous recital at a church social.’ And added, ‘Can one imagine any private soldier, in the nineties or now, reading Barrack-room Ballads and feeling that here was a writer who spoke for him?’

The case remains, perhaps, unresolved. Like Dickens in ‘his’ London, Kipling is our greatest witness for ‘his’ India and has stamped his version on posterity. And for me there is a greater question: whether or not Kipling invented the modern soldier, did he also create the modern Cockney. The type, of course, was long-established. The term, which meant a mother’s darling, had been used of Londoners since the 17th century and embraced all, rich and poor. Its movement had been socially downhill, though John Jorrocks, star of Stalky’s beloved Surtees, was wealthy and a Cockney – and proud of both. As for Cockney speech, the mid-century’s exemplars was Dickens’ Sam Weller. Sam has been characterized as coming from the comic servant tradition, perhaps so, but his speech patterns – not least his characteristic ‘v’ for ‘w’ substitution – can be found in other books of the time. Stylistically Weller is followed by E.J. Milliken’s monstrous creation, ’Arry, who flourished in Punch for 20 years from 1877. A modern ’Arry might be labeled a chav, but he rises far above the underclass in aspirations, social encounters and loudly voiced opinions: traditionalist, jingoistic and unashamedly conservative. (An older Kipling, one might suggest, might have appreciated him). He appears in the form of slang-heavy verse letters to his country friend ‘Charlie’, five or six per year.

Milliken described his creation thus:

‘As to ‘Arry’s origin, and the way in which I studied him, I have mingled much with working men, shop-lads, and would-be smart and “snide” clerks — who plume themselves on their mastery of slang and their general “cuteness” and “leariness.” My ’Arry “slang” is very varied, and not scientific, though most of it I have heard from the lips of street-boy, Bank-holiday youth, coster, cheap clerk, counterjumper, bar-lounger, cheap excursionist, smoking-concert devotee, tenth-rate suburban singer, music hall ‘pro’ or his admirer,” etc. etc.’

I am not sure whether Kipling read Punch nor if so whether he would have paused at ’Arry. I assume he would have loathed him, though he might have admired his creator’s artistry. In their respective vocabularies ’Arry and Kipling’s expatriates and soldiers overlap 97 times but that might be pure coincidence. This was the language of a certain type at a certain time. Again, it is Kipling’s observation that one must admire. (He also uses a dozen words that Weller pronounces in Pickwick).

’Arry is good for 1000 citations and Milliken’s list displays a far wider range of sources than Kipling could have experienced. That noted, and on the evidence of Kipling’s best-known cockneys – Ortheris and Badalia Herodsfoot – I find it hard to follow P.J. Keating’s claim that Kipling had not merely brought to life the world of Tommy Atkins (a nickname he had not invented but popularized as never before) but had also made ‘a complete break with convention and given English fiction with a new cockney archetype’. Of the Soldiers Three one is stage Irish, one from Yorkshire, and thus dialectal, and Ortheris, the Cockney (who would presumably have called himself ‘Aw’fris’), is relatively quiet, or at least as compared with the loquacious Mulvaney. As Orwell noted, Kipling concentrated less on word than on delivery and Ortheris ‘is always made to speak in a sort of stylized Cockney, not very broad but with all the aitches and final ‘g’s’ carefully omitted.’ His vocabulary is far smaller and far more mundane than is that of the self-consciously worldly ’Arry, but his background is much poorer, while ’Arry is more lower-middle than truly working-class.

The late 19th century saw the appearance of a group who, in fictionalizing life in the East End, became known as the ‘Cockney novelists’ . These were Arthur Morrison, William Pett Ridge, Edwin Pugh and others. Whether like Morrison purveying the East End’s lowest depths, all drunken violence, poverty and crime, or like Pugh or Pett Ridge counterfeiting a level of cheery optimism that would in time be reworked as the Blitz spirit, these writers chose to stay within their environment. Kipling ranged far wider, but in 1890 he did make one foray into the East End, and in so doing gives us another chance to assess his version of Cockney speech.

Kipling was appalled by London, hating its foggy weather, its dirt (both literal and metaphorical), and appalled by its human beings, whether the ‘long haired things / in velvet collar rolls’ or what he generalized as a drunken, violent underclass. His single essay into the city’s eastern squalor, ‘The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot’, is unsparing. It is the story of an East End slum woman who volunteers her local knowledge to augment and improve upon the church’s official charitable work and who, even after being kicked almost to death by her drunken husband, still refuses to betray him with her final breath. Like Dicky Perrott, wretched focus of Arthur Morrison’s Child of the Jago, she is unable even in extremis to abandon the code of the slums. In its unyielding pessimism Kipling’s tale is all Morrison and offers not a vestige of Pugh or Pett Ridge. J.M. Barrie dismissed it as ‘merely a very clever man’s treatment of a land he knows little of’ and suggested that ‘the dirty corner is Mr Kipling’s to write about if he chooses’ but Barrie was far happier in Kensington Gardens.

As he had treated it in his Indian stories, Kipling’s creation of Cockney speech patterns lie more in dropped initial h’s and final g’s, double negatives and eye-dialect than in slang as such. Thus ‘port wine’ is ‘pork wine’, a ‘curate’ a ‘curick’, ‘diptheria’ ‘diptheery’, ‘what’, as similarly pronounced by Ortheris, is ‘wot’, and so on. Like Tommy Atkins, their cousin overseas, these East Enders have a vocabulary of ‘less than six hundred words, and the Adjective.’ There is slang, but it is of the quotidian sort, including slop (policeman), garn!, shut your head, and the epithets blooming, blasted, and bleeding.