Foxx Nolte's Blog

July 9, 2024

The Lost Music of Frontierland, 1971 - 1990

Eleven years ago I began to document my journey to recreate and collect old music loops which played at Walt Disney World in its early days. I started with a few easy ones, proceeded through obscurities and new discoveries, but all through the process one of those really early music loops was seemingly lost forever.

Eleven years ago I began to document my journey to recreate and collect old music loops which played at Walt Disney World in its early days. I started with a few easy ones, proceeded through obscurities and new discoveries, but all through the process one of those really early music loops was seemingly lost forever.I'm delighted to return with news that the last major 1970s music loop has been recovered, meaning we now have accurate background music for the whole of Magic Kingdom. That final missing piece of the puzzle was Frontierland, and it has quite a story behind its recovery.

Frontierland would seem, on the face of it, to suggest an obvious musical background. The logical choice to reach for is western movie themes, and that's what Disneyland and Disneyland Paris have done since the the 90s. But in the 1970s those films were still relatively recent, and may have been cost prohibitive to license. Disney really only played movie tunes around its front entrance in those days, and so Jack Wagner had to decide what a "Frontierland" would sound like for Magic kingdom's opening in 1971.

You can hear the resulting odd mix of folk tunes for yourself; it survives as a direct tape said to come from Jack Wagner's collection, dated 1973, and probably preserved by Mike Cozart.

Frontierland 1971 (?) - 1975

01. Old Betsy [5]02. Bile'em Cabbage Down [5]03. Red Wing04. Golden Slippers05. Tangle Weed [4]06. Swanee River07. You Are My Sunshine08. Tomahawk [4]09. Down Yonder10. Swinging Doors [1]11. Love is Just a Four Letter Word [2]12. Chicken Out (Joann's Theme) [3]13. Buffalo Gals14. Devil's Dream15. Red River Valley16. Old Joe Clark17. Unknown

18. Red River Valley [5]19. Polly Polly Doodle [5]20. Wabash Cannonball [5]

[1] The Buckaroos Play Buck and Merle by The Buckaroos[2] Nashville Rock by Earl Scruggs[3] Norwood: Music from the Motion Picture by Al De Lory[4] Square Dance Tonight by Tommy Jackson[5] "Mile Long Bar" BGM; George Bruns

OK, already there's some oddities to point out.

The first is the issue of the "Mile Long Bar" music, which is a can of worms all its own. This music was evidently overseen by George Bruns and was recorded in-house, at least partially with the Stoneman family (see my piece on the Country Bear Jamboree music here). It was then used in a variety of sources including the Mile Long Bar, Hungry Bear Restaurant at Disneyland, and certain tracks were issued on the Country Bear Jamboree LP from 1972.

The first is the issue of the "Mile Long Bar" music, which is a can of worms all its own. This music was evidently overseen by George Bruns and was recorded in-house, at least partially with the Stoneman family (see my piece on the Country Bear Jamboree music here). It was then used in a variety of sources including the Mile Long Bar, Hungry Bear Restaurant at Disneyland, and certain tracks were issued on the Country Bear Jamboree LP from 1972.For a long time, the six tracks released on the LP were the only ones known to exist, and since the LP itself calls out the tracks as being from the "Mile Long Bar at Walt Disney World", that's what we know it as. However, its' also become clear over the years that more than these six tracks were recorded for an unknown purpose, and no source for all of what was recorded seems to exist. In other words, I believe these tracks were recorded as background music, possibly for all of Frontierland. This would explain why Jack Wagner sprinkled them heavily into the loop he ended up creating.

And about that original loop - its fast, but not really high energy, and not very appealing. Honestly, my main motivation for not covering it when I covered all of the other Magic Kingdom loops was because I didn't like it and was holding out hope for the rediscovery of its predecessor. In the past on this blog I've suggested that early BGM with odd "tones" could possibly be due to Jack working mainly off concept art and descriptions before the opening of the park. That is just a theory, but it does make sense of Jack reaching for honky tonk piano music. There's a definite lack of a "Hollywood West" feeling in this loop, which is the sound and tone most are going to expect out of a Frontierland.

There is one scrap of evidence of the music actually being played in park, which is this 1975 video of sound b-roll, in which Devil's Dream can be heard at 05:00:

However, with the introduction of expanded area music played throughout Magic Kingdom in 1975, Jack tried again. If there was any piece of early Magic Kingdom music I was ready to declare "lost media", it was this 39 minute 1975 atmosphere loop, and I'm incredibly pleased to finally be able to post it.

Frontierland 1975 - 1991

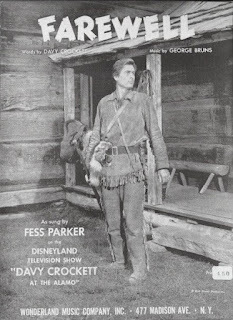

01. Farewell (to the Mountain) [1]02. Bearless Love [1]03. Bile 'Em Cabbage Down [1]04. The Town and Country Square Dance [2] 05. Western Saloon [3]06. Blackberry Blossom [4]07. Country Guitar [5]08. Buffalo Girls [4]09. Country and Western No. 1 [6]10. Country and Western No. 2 [6]11. Country and Western No. 3 [6]12. Cripple Creek [4]13. Country Banjo [5]14. Country and Western No. 4 [6]15. Country Harmonica [5]16. Country and Western No. 5 [6]17. Dusty Miller [4]18. Buffalo Gal [7]19. Country and Western No. 6 [6]20. Flop Eared Mule [8]21. East Tennessee Blues [4]22. Evening Campfire [3]23. Skip to My Lou* [9]

[1] Mile Long Bar BGM, George Bruns[2] Town and Country Square Dances (Everest Records 1960)[3] Media Music Release No. 2 - No. 4 Western Themes/Fun Marches by Ib Glindemann[4] Square Dance Festival, Vol.1 by Tommy Jackson[5] Media Music Release No. 7 - No. 5 - Solo Instruments by Henrik Nielsen**[6] Media Music Release No. 6 - No. 8 - Special Occasions / Country & Western by Henrik Nielsen[7] Country Honky Tonk Piano by The Nashville Four and "Slim" 88 Wilson[8] Come On In! We're Pickin' and Singin' Folk Songs by The Wanderin' Five[9] Instrumental Music Of The Southern Appalachians (Tradition Records, 1957)

* Edited to repeat a section, so the track is 0:00.658-1:03.615, then repeats 0:41.927-1:03.615, and finally repeats 0:41.927-0:43.728** There are 30 second versions and 60 second versions recorded of all of the tracks on this record; the loop exclusively uses the 60 second versions.

I think this effort is a lot better. The whole thing seems to be structured around the square dance and Capitol Media Music tracks, and selections were made with an eye on keeping the energy levels high. Every so often the loop slows down for a solo or a more sedate selection, but never for long. Given that many of the Media Music tracks were intended for commercials and top out at a minute long, there isn't much time for anything to outstay its welcome.

I noted this difference when editing the second version of my Musical Souvenir audio project, and it's impressive. This music could still be playing in Frontierland today and not feel dated.

And is there a lot of weirdness to point out about this loop! Again it begins with Mile Long Bar music, except different selections, then proceeds through folk music from highly obscure sources. Jack Wagner had contacts at record companies all over Hollywood, and he must have worked overtime on this one to secure clearances on some of the cheapest music imaginable (for his masterpiece in this department check out That Infernal Swiss Music).

Tommy Jackson returns from the earlier loop, but from a different record. The tracks from this Tommy Jackson Square Dance Festival album would go on to be almost as much of a stalwart of Walt Disney World as Frontierland itself, being used in The Land pavilion and, most memorably to this author, as the "Country Bear Jamboree" music used in the "A Day at the Magic Kingdom" souvenir VHS.

And then there's the Capitol Media Music line, already covered in my piece on Tomorrowland's early music. The Henrik Nielsen "Country & Western" tracks still kick around the Disney ecosystem in places like Disneyland Paris. "Western Saloon" by Ib Glindemann played at the entrance to Disneyland's Frontierland all through the 70s and 80s. The Capitol tracks really help this loop feel more cinematic, which is really what Frontierland is about.

But it's "Evening Campfire" that will send many Gen Xers a-tingling, because it's the same track used in the 1970s "Mighty Dog" dog food commercials. It's this track that Mike Cozart remembered playing at Magic Kingdom, then again at Disneyland in the late 90s, which made it possible to recover this loop at all:

For a very, very long time this track was lost with no real hope of being found, so the story of how it appears here today is worth recounting. Frontierland 1975 was not one of the tracks preserved by Mike before the death of Jack Wagner. Michael Sweeney and I had put together some observations based on home videos and had a handful identified tracks, but we knew we were on the right track due to Mike Cozart's recollection of "Evening Campfire".

Mike also recalled that this loop, or one very much like it, playing at Disneyland in the late 90s at a "Chip n Dale" meet and greet. Again, the defining song was "Evening Campfire". And there, it seems to pass out of history.

Except!

Except!Flash forward to 2022, when MouseBits member Pixelated noted that at least something very similar to this "Chip n Dale" loop was playing inside the Golden Horseshoe. This allowed Aubrey at DLRmusicloops to get a full recording, which as it turns out exactly synched with the partial reconstruction Michael Sweeney had begun back in 2012. The only difference was a single track, "Home Sweet Home" instead of "Bile 'Em Cabbage Down".

Except, there was still one unknown track. It was found in higher quality in the collection of WaltsMusic, where it was labeled as part of a recording called "Mile Long Bar #4". This meant the unknown song was recorded by Disney and George Bruns, dashing hopes of locating it commercially. Finally, Disney music super guru DisneyChris jumped in with the right answer: it was "Farewell", from the Davy Crockett television series. This song was composed by George Bruns to fit an actual poem written by the real Davy Crockett.

And with that, the long lost music loop was recovered. If we count Mike Cozart noticing the loop playing at Disneyland in the late 90s, it took many Disney music nerds over multiple generations to put the pieces together over a span of almost thirty years. Remarkable.

Let me be clear here... this is not the end of the story. There are still lots of vintage pieces of background music that remain unrecovered, and likely, unrecoverable. Music played in restaurants, and shops, and resorts, and weird places like the Kennel that you wouldn't even think of. But in terms of music you would recognize and remember, we now have a full representation of Magic Kingdom from 1971 until the present day. Its amazing, and I'm honored to be have helped steward the musical legacy of this park in the way I have.

July 8, 2023

Off Site: Walt Disney World Vs. Their Own Customers

This article written for MiceChat in April and June 2023 explores all of the ways Disney has tried (and mostly failed) to control their paying customers, from 1955 and leading to the present day. It also includes a story I've never shared publicly that greatly influenced my decision to leave Disney in the late 00s.

June 14, 2023

Off Site: Disney World's Bermuda Triangle

In the interest of maintaining a complete index here, I'm cross-linking to the articles I've done for MiceChat while writing my second book. This is one of my recent favorites, an imaginative "interpretative history" of one of Walt Disney World's strangest corners. If you missed this one it's some of my best work:

https://www.micechat.com/319186-the-mystery-of-walt-disney-worlds-bermuda-triangle/

Off Site: The Haunted Mansion and Inventing Halloween

In the interest of maintaining a complete index here, I'm cross-linking to the articles I'e done for MiceChat while writing my second book. I did this piece in 2021 - for what was supposed to be Halloween - celebrating that great American tradition and the Haunted Mansion's place in it:

December 11, 2021

Disney Annual Reports 1965 - 1975

As a Disney parks fan, it can be easy to feel like I missed all the good stuff. Adventure Thru Inner Space! Mine Train Thru Nature's Wonderland! America Sings! Cinderella Castle Mystery Tour!

This, of course, is nonsense. Simply having experienced every one of the original EPCOT Center attractions puts me in fairly elect company, and as always, such things are always a matter of timing, dumb luck, and opportunity.

One of those timing opportunities that actually landed me in the plus category was moving to Florida when I did, which gave me access to opportunities to look at and acquire paper goods, magazines, and primary source documents at a time when being into Walt Disney World history was a pretty niche pursuit. The prices that certain things I paid a few dollars for can fetch online can be pretty eye-watering, and while the COVID pandemic has seemingly slowed down some of the worst excesses, I feel lucky to have a library of several thousand paper items that are absolutely the bedrock of the research for site. I feel lucky to have them and I'm worried about younger Disney history buffs who probably won't have access to these things in the future. Until such a time that a fan-organized library can be created that's open to the public, too much of Disney history is dependent on being able to buy your way in through pricey editions or secondhand collectibles. I don't like that.

So I'm going to do something about it. I've determined to start dumping some of these less-accessible treasures online in properly scanned versions. I'm not going to be a weenie about it and cover them in watermarks. I want these to be available to everyone. My only request is that if you are a historian or author and you use any of these please credit the "Passport Free Library" and this site in your citations.

I'm going to start with the WDP Annual Reports, all scanned by me (some from copies at the Orlando Public Library, which is where this project began). These fascinating and colorful little books are where so many of my research efforts have begun, it seems right to launch this project with them.

Even if you don't care about financial statistics, you absolutely should download and enjoy these, as they're absolutely bursting with construction shots, concept art, descriptions of doomed plans, and general vintage Disney weirdness.

Download, share, and enjoy them at your leisure..!

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1965

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1966

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1967

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1968

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1969

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1970

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1971

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1972

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1973

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1974

Walt Disney Productions Annual Report 1975

More content coming as I can get things scanned...!

November 21, 2021

The Passport Free Library

Welcome!

This hub page on the blog Passport to Dreams Old & New is a collection of free primary source resources for Disney fans and historians looking to do some research into aspects of Disneyland, Walt Disney World, and Walt Disney Productions. These are downloadable, searchable, and shareable.

If you are a historian or author and you use any of these please credit the "Passport Free Library" and this site in your citations.

(Contents Coming Soon!)

Other Resources:

History of Disney Theme Parks in Documents

October 13, 2021

Sonic the Hedgehog Could've Saved DisneyQuest

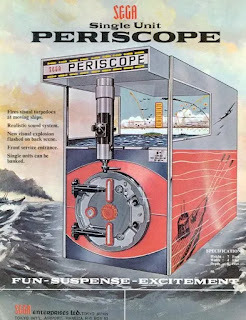

In the 1980s and 90s, Sega was the king of arcades in Japan, and they had a plan.

Sega - SErvice GAmes - was actually originally an American company, distributing and servicing pinball machines in American army bases in Hawaii. With the expansion of US troops to places like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, Sega expanded with them.

By the 1960s, Sega was producing elaborate electro-mechanical games like Gun Fight and, most famously, Periscope - huge, eye-catching things full of clever gadgets to gobble up quarters. They were purchased by Gulf + Western in 1969, just on the brink of the explosion of video-based arcade games. By this time Sega was headquartered in California, with a significant secondary office based in Japan.

By the 1960s, Sega was producing elaborate electro-mechanical games like Gun Fight and, most famously, Periscope - huge, eye-catching things full of clever gadgets to gobble up quarters. They were purchased by Gulf + Western in 1969, just on the brink of the explosion of video-based arcade games. By this time Sega was headquartered in California, with a significant secondary office based in Japan.Sega’s first foray into actual arcade ownership came in 1975-6, when they purchased a chain of Southern California arcades called Kingdom of Oz. At this time arcades were actually banned in many cities across the country, a holdover from a previous generation’s war against gambling. Sega won over these municipalities by opening modern, clean, brightly lit arcades that used tokens, not quarters.

This brief flowering, however, would end with the infamous video game crash of 1983, whereupon Sega sold their locations to Time Out arcades. Sega as a corporate entity sold out as well - Gulf + Western was divesting themselves of assets, and Sega was folded into Bally. This was the official end of Sega of America, in the sense of being an American-based company. Sega of Japan organized a management buyout in 1984, and when Sega of America emerged from their partnership with Bally in 1985, Sega of Japan bought them too. In the course of two short years Sega went from an American arcade pioneer to being largely based in Tokyo. All of this background information will be relevant later, I promise.

As an arcade developer of the era, Sega was respectable but second tier. They produced their own weird knockoffs of Space Invaders and Pac-Man, just like the rest of the video game industry. Even their Japanese home console, the SG-1000, was a distant second to Nintendo’s Famicom. But all of that changed in 1985 with the introduction of Yu Suzuki's Hang-On. Hang-On wasn't too different from other race games of its era, but what made the difference was the arcade cabinet - a scaled down motorcycle that players steered by shifting their weight. The game was a smash hit everywhere, and Sega had discovered their metier.

As more and more of these massive machines made their way to arcades, SEGA began to increasingly resemble a theme park operator, and their "rides" were amongst the most profitable in the business. But these indoor simulators, bumper car tracks, and more were just too big for most arcade operators, so Sega built their own facilities to house them. This was based pretty much on the model Sega had pioneered in the arcade space - bright, modern, clean.

Sega hoped that they could grow this concept internationally - walled gardens of amusement rides and video games that were owned by Sega. They basically wanted to turn their arcades into theme parks.

Sega dubbed this dream “Joypolis”. This is the story of that dream, the international conflicts that derailed it, the market realities that buried it… and, finally, the mouse that stole it. Because the story of Sega Joypolis is also the story of DisneyQuest, Disney’s very own copycat that outlived the original. Insert your quarter and buckle up.

--

Curtain up. A bare stage. Suddenly, two figures appear on either end of the stage. They want to dance together, but they also kind of hate each other. Let’s get to know the two sides of this tango.

First, Disney. You know Disney. Disney kinda sucks at video games.

It's weird, right? They've probably inspired more video games and designers than any other company, but their own in-house efforts in the field have consistently fallen short of expectations. This is nothing to sniff at - video games generated some $180 billion in revenue in 2020, a year that saw other entertainment sectors flagging behind due to the COVID pandemic.

But Disney just kinda sucks at video games, epitomized by the spectacular crash and burn of their toys-to-life game Disney Infinity - the market leader! - in 2016. Going back a few years before that, an ambitious attempt to create in-house prestige titles was sunk by the disappointing market debut of Warren Spector’s Epic Mickey and a subsequent management shuffle. From there you have to go back to the 8 and 16 bit era to find Disney video games that anybody cares about, and none of those were actually made by Disney.

Now, Sega.

In the West when we think of Sega we tend to jump immediately to home game consoles. Sega's console division had begun relatively inauspiciously in the early 80s with their SG-1000 system - a plastic box roughly comparable in power to the ColecoVision. Sega had the misfortune of launching their system on the very same day as the release of the Nintendo Family Computer, which you know under its international name - the Nintendo Entertainment System. The SG-1000 never had a chance.

But Nintendo couldn't be everywhere, and in markets that were underserved by the company, Sega found they could get a foothold with their next 8-bit console, the Master System. The Master System was a modest success in the US and Japan, but in places like Brazil and the United Kingdom, it ate up the entire market. Yet Sega's eyes were always on the prize of capturing North American market share away from Nintendo. To aid and abet them on their quest, they hired the former CEO of Mattel to run their American division - Tom Kalinske.

Chances are if you are a Gen Xer or elder Millennial who remembers Sega, you remember them almost entirely for what Kalinske brought to the table. To push Sega's new 16 bit console the Mega Drive - which Sega re-dubbed the Genesis - Kalinske ordered an aggressive marketing campaign that attacked Nintendo as a baby's toy. He signed celebrity endorsements left and right, he expanded Sega's market share, and as a crowning achievement, oversaw the launch of a character platform game designed expressly to appeal to Americans. It starred a red, white and blue Mickey Mouse with attitude named Sonic the Hedgehog. And it worked.I'm not going to go into this in too much detail, because even if you haven't read Console Wars you probably know the basics of this... Sega vs Nintendo has gone down in history with the patina of folklore upon it, the Pepsi vs Coke for those alive in the age of the POG.

But what is important to stress here is that Kalinske did his job so well that he actually made a lot of enemies over at Sega of Japan. Japanese corporate culture is even more insular and cutthroat than it is in America, and the booming success of the Sega brand in the US and Europe was considered an embarrassment in Japan. Sega Japan's Mega Drive was an also-ran in the console market, a distant third behind consoles by Nintendo and NEC. The only area in which Sega truly could be said to dominate is in the arcade.

All of this set the stage for a showdown.

Big in the Nineties

Meanwhile, a continent away, the early 90s were a difficult time for Disney theme parks. Disney had opened the Disney-MGM Studios in 1989, a half day park rushed out the gate to beat Universal Studios Florida to the punch. But the early 90s were a recession era, and the crowds coming to Orlando were insufficient to support what was there.

The park that suffered the most was Epcot, which had neither attractions old enough to be seen as classics nor attractions new enough to seem exciting. Through this era it wasn't uncommon for Epcot to be closed one day a week. It was also a victim of bad timing: Disney had built a park based around science and technology at the very start of when science and technology were about to blast off like a rocket. The difference between a cutting edge computer from 1982 and one from 1988 was jarring. Much of the technology on display in EPCOT Center's Communicore area was forward-thinking for 1982, looked just about current through 1989, and antiquated by 1992. As the first area guests encountered while entering Epcot, it needed a radical re-think.

FigmentJedi on Flickr

FigmentJedi on FlickrThe Imagineer who got the new version off the ground was Barry Braverman; the story told is that he got Innoventions approved in a single day by picking up the phone and cold-calling corporations. Taking inspiration from trade shows like CES and the Ginza district of Tokyo, the new exhibit area was dark and neon-lit where CommuniCore was bright and open; the sidewalks in front of the attraction entrance sparkled with fiber-optics. Inside were exhibits from Apple, Hammacher Schlemmer, General Electric, with Disney shows featuring Aladdin and Bill Nye. It was the 90s distilled, the last time EPCOT could truly be said to be presenting a glimpse of the future. As Eisner said, "Almost every company that's involved in Innoventions is the leading company in its field." And the killer exhibit in it all was SEGA.

Sega and Disney had extensive ties in 1994. Back in 1982 as part of the dissolution of Gulf + Western, Sega had been moved into closer alignment with Gulf-owned Paramount Studios, resulting in guess-who Michael Eisner sitting on Sega’s board of directors.

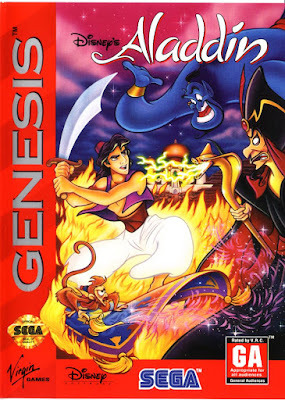

In recent years, as part of Kalinske's initial effort to shore up Sega's brand recognition in the United States, he went on a celebrity endorsement spree. Kalinske knew that Sega needed a platform mascot game to compete directly with Mario, but Sonic the Hedgehog was still a year away at this point. What to do? Sega signed a character every American knew: Mickey Mouse.

In recent years, as part of Kalinske's initial effort to shore up Sega's brand recognition in the United States, he went on a celebrity endorsement spree. Kalinske knew that Sega needed a platform mascot game to compete directly with Mario, but Sonic the Hedgehog was still a year away at this point. What to do? Sega signed a character every American knew: Mickey Mouse.The resulting game, Castle of Illusion, was a success for Christmas 1990, resulting in a sequel and a raft of Genesis-only Disney games themed to Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Beauty and the Beast. But the capstone of this collaboration was undoubtably Disney's Aladdin, a game for which Walt Disney Feature Animation worked with Virgin Games to bring eye-popping, smooth 2D cartoon graphics to the system. It was a system seller; Aladdin remains the third highest selling Genesis game.

1994 were banner years for both Disney and Sega, with The Lion King in theaters and the Tower of Terror opening at Disney-MGM Studios. Sega was riding high on the success of Sonic the Hedgehog, an early 90s phenomenon to rival Bart Simpson. The Sonic and Knuckles game was arriving in November, with its memorable lock-on gimmick. Sonic was the centerpiece of the Epcot Innoventions exhibit, triumphant amidst a riot of motion and color. The Sega exhibit was pure adrenaline brain candy for 90s kids, and few who saw it in person have ever forgotten it.

Upon entering, guests were greeted by an enormous Sonic the Hedgehog statue holding a golden ring. At the base of the statue, potential customers could sit and play Sonic 3 on Genesis with a 5 minute time limit. This was the "Future" area. One wall in the "Arcade" area featured a huge setup of Virtual Formula arcade cabinets, a simultaneous multi-player racing game in scaled-down F1 cars. Other areas included "Action Adventure" and "Kids", which featured tiny game stations appropriate for the 5-7 set. Nearly every foot of the space was crammed full of Sega games and sparkling with lighting effects, and it was entirely possible to lose an hour or two just in that one area; most of us kids who saw it in person did just that.

If we stop the clock right here, in summer 1994, it looks as though nothing could stop Sega or Disney and the future was nothing but roses. But both companies were sailing directly into some pretty choppy waters.

The Saturn Debacle and Backstabbing

The split between Sega Japan and Sega of America had resulted in two companies that had very different strong suits and very different business philosophies. Despite a growing reliance of Sega of America on Western development houses, Sega's hardware division in Japan still called the shots in the creation of the companies' hardware products - the core of the company.

In early 1994, Sega of Japan pitched Sega of America on a new, upgraded version of the Mega Drive / Genesis. The 16 bit console was at best a cult hit in Japan, but in the US, Europe, and South America was the market leader, having successfully pushed Nintendo into second place thanks to aggressive marketing, price cuts, and Sonic the Hedgehog. The peak of their success was no time to unleash a new version of the same machine. Head of Sega of America R&D Joe Miller reportedly exclaimed:

"Oh, that's just a horrible idea. If all you're going to do is enhance the system, you should make it an add-on. If it's a new system with legitimate new software, great. But if all it does is double the colors.."

The two parties agreed that Sega of America could move ahead with the project as an add-on to the existing Genesis as a way to extend its lifespan in the markets where it had been most successful.

I must point out here that at this time Sega of Japan was a Borges Palace of intrigue and skullduggery. The company (Japan) was actually developing not one, but two 32-bit consoles simultaneously, and now had just effectively given their American arm the green light to go ahead with a third. None of these three teams were told about the existence of the other.

I must point out here that at this time Sega of Japan was a Borges Palace of intrigue and skullduggery. The company (Japan) was actually developing not one, but two 32-bit consoles simultaneously, and now had just effectively given their American arm the green light to go ahead with a third. None of these three teams were told about the existence of the other.At the time it was well-known in the industry that Sony was working on a console of their own, to be based around CD media and using polygon technology. Nintendo had partnered with Silicon Graphics to bring some form of their 3D technology to home consoles. Sega's plan was to beat both consoles to market and eat their lunch. Almost everything about the resulting product, the Sega Saturn, is an astonishing saga of failure. But this is a blog about theme parks, not video games, so all that's important to know here is that Sega of Japan had more or less set up Sega of America to fail.

And fail they did! The add-on they had agreed to produce became the Sega 32X, a mushroom-shaped blob of plastic which pretty much was a separate, smaller Sega Genesis which mounted atop the original console. Launching at the astonishing price of $160, the 32X failed to garner much market support and did a lot to erode Sega's brand image. Sega of America producer Scot Bayless later said:

"Frankly, it made us look greedy and dumb to consumers - something that a year earlier, I could've have imagined people thinking about us. We were the cool kids!"

Sega of Japan didn't much mind; they released the Saturn in Japan at the same time and it sold very well. Having declared victory over Sony and Nintendo on all three companies' home turf, they gazed across the ocean to the slow uptake of support for the 32X, which Sega of America had spent $10m to launch. If it worked once, it would work again, and Japan ordered Tom Kalinske to move ahead on pushing the Saturn onto store shelves as quickly as possible.

The problem here, of course, is that Sega had nothing to lose in Japan, but they had everything to lose literally everywhere else, and Kalinske knew it. Developers and retailers were promised a Christmas 1995 launch window on the Saturn and needed Sega to stick to that date to allow their business partners to be ready to support their product. Gamers had just been sold a $150 add-on and would feel burned by an early roll-out of the next big console. Despite protests, Kalinske went to the very first E3 in May 1995 and announced that the Saturn was available, right now, at a price of $399. That's the modern equivalent of about $700.

In the next presentation, an executive of Sony of America approached the podium, announced the price of the Sony Playstation - $299 - and sat down. The room erupted in cheers. The 32 bit console war had been won before it started.

Expansions and More Backstabbing

Meanwhile!

The Disney Decade wasn't going so well. Eisner had opened EuroDisney with an astonishing seven hotels. Despite the park doing modestly well and starting to build a following, there was simply no way for the park to be fully solvent because of all of those money-draining empty hotel rooms.

Elsewhere, costs were ballooning on feature animation, and although nobody knew it at the time, The Lion King was going to be the high water mark, followed by ten years of diminishing returns. Jeffrey Katzenberg had resigned from Disney in August 1994 when Michael Eisner had failed to promote him to Frank Wells' old position; Katzenberg would head off to form Dreamworks Animation and eat Disney's lunch through the 2000s. Just as badly, Disney had just been spectacularly shot out of the sky by Prince William County, Virginia for the Disney's America project in September 1994.

Suddenly, the mood in the executive suite changed rapidly, and word came down from on high that Disney would no longer be building theme parks. I don't need to point out that this is complete craziness, especially in the 90s with all those fat Clinton-era dollars flying around the country. But that was the decree, and it would shape much of Disney's business decisions in the late 90s.

At the same time Sega was still hoping to bring their arcade chain Joypolis to overseas markets. Sega had provided the arcade cabinets for the "Arcade des Visionnaires" at Disneyland Paris in 1993 or 1994. They also saw an opportunity in the United Kingdom, a region Sega had been the market leader in since the 80s. The very first first overseas Sega World opened in Bournemouth in 1993, and Sega set their sights on London.

Enter, the London Trocadero!

I have to explain what this thing was before we move forward. The Trocadero was a massive restaurant complex sitting vacant in the heart of London, as it had since closing in 1965. At some point it passed into the hands of an anonymous group known as the Electricity Supply Nominees, a group who apparently handed pensions. The ESN in 1978 presented and was approved to turn the cavernous space into what they referred to as an "entertainment destination", but really was quite simply a mall. This was part of a larger effort on the part of London to clean up Piccadilly Circus, a precursor to the Disneyification of Times Square. The interior was turned into a succession of terraces ringing a central courtyard very much like those seen in any other 80s mall. Opening in August 1984, the Trocadero housed a scattershot collection of complete nonsense including an HMV Records, a food court themed to international cities, Shaftbury's On the Avenue Discotheque, and an exhibition based around the Guiness Book of World Records. Sounds promising???

The Trocadero's Mall Phase...

The Trocadero's Mall Phase...The Trocadero was never the hit that was expected, and tenants (and owners) came and went quickly. In 1993, the basement area became home to Alien War, a kind of walk-through haunted house based on the Aliens franchise. But with vacancies increasing in the complex, new owners were looking for a more dramatic solution just at the time Sega was looking for a splashy new facility in the tourism center of London. Sega rented the entire Trocadero and spent $45 million converting it into Sega World London.

All of these disparate strands finally begin to come together here. Disney took an interest in Sega's venture, planting the seeds that would become Disney Regional Entertainment's signature concept: DisneyQuest. Imagineer Tom Morris remembered the early days of the project:

"I believe it came about because [Sega] was interested in a partnership, so that [DisneyQuest] would be leveraged with a big player. Someone gave me a tour of a huge arcade just off of Picadilly Circus in London. [..] It was five or six stories, and they had a big escalator that went through the middle of it, but there wasn't really an attempt to create an organizing principle behind it. So we had that to benchmark with, and there was a similar thing in Paris... then we decided to go to Japan to see the facilities Sega had created called Joypolis."

This seems to have been a real thing, with Sega CEO Hayao Nakayama working closely with Imagineering to develop the concepts.

At the same time, Disney was touting Sega as a potential tenant of their proposed hotel/retail complex on Times Square. This hotel would never come to be, but the mere fact that Disney was willing to name-drop Sega in front of the government of the City of New York is telling. That was in early May 1995. Across the country in Los Angeles, Tom Kalinske was announcing the surprise launch of the Sega Saturn.

Work on Sega World London progressed quickly. Sega built a huge escalator that would bring customers from the entrance ticket booths to the top floor of the Trocadero amongst a futuristic blinking light show. The rest of the facility would be experienced moving from floor to floor in a downward spiral, with each floor having thematic groupings of arcade machines ("Sports Arena", "Carnival", "Flight Deck", etc) and one or two major attractions on each. Besides the large attractions, the facility had a McDonalds, a children's play structure, a bar, and of course... a Gift Shop.

...And what Sega turned it into.

...And what Sega turned it into.The major attractions on each floor varied in size and complexity. The downstairs "Sports Arena" area with the bar had a few Sega AS-1 simulator machines, including one showing "Michael Jackson in Scramble Training". There were at least two other simulator attractions: Aqua Nova/Planet, a Star Tours-style motion simulator with 3D glasses and a scoring system, and Space Mission, which used a motion platform and ran off Sega's VR-1 headset system.

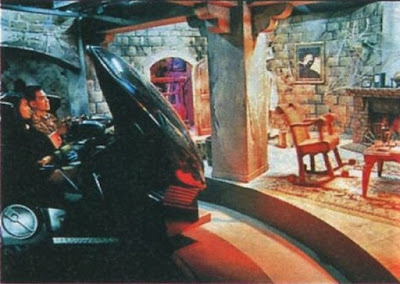

"Ghost Hunt" in Osaka JoypolisOf more interest to theme park fans are three more traditional themed attractions. The least impressive is Beast in Darkness. This seems to have been a walk-through haunted house which primarily used audio elements to convey the impression of being stalked by a huge monster. Far more impressive is Ghost Hunt, an honest-to-goodness ride-through haunted house attraction. Unlike at Buzz Lightyear or Sally's Boo Blasters, the ghosts in this one took the form of computer generated images that appeared on a transparent windshield between the riders and the sets, meaning Sega was using Augmented Reality back in the 90s.

"Ghost Hunt" in Osaka JoypolisOf more interest to theme park fans are three more traditional themed attractions. The least impressive is Beast in Darkness. This seems to have been a walk-through haunted house which primarily used audio elements to convey the impression of being stalked by a huge monster. Far more impressive is Ghost Hunt, an honest-to-goodness ride-through haunted house attraction. Unlike at Buzz Lightyear or Sally's Boo Blasters, the ghosts in this one took the form of computer generated images that appeared on a transparent windshield between the riders and the sets, meaning Sega was using Augmented Reality back in the 90s.And the final attraction we should all recognize is Mad Bazooka, which Disney copied pretty much directly for DisneyQuest.

Yep.

Yep.But...! In September 1995 Sega announced that they would be moving forward to bring their arcade locations to the US... not with Disney, but with DreamWorks SKG. They hoped to open 100 locations by 2002.

It's hard to know exactly what to make of this, though a deciding factor may not have been Jeffrey Katzenberg but Steven Spielberg. Spielberg was and is a video game enthusiast; he included Sega’s “Killer Shark” electromechanical game in Jaws as a throwaway joke. Spielberg actually helped design an attraction called "Vertical Reality" that appeared at GameWorks locations. David Kaplan in Newsweek described this as such:

"Vertical Reality consists of an enormous central column of three video screens, rising 25 feet to the ceiling, replicating a skyscraper. Twelve players, arrayed in a circle, are strapped into seats that climb up a pole. Each player gets a cybergun to kill cyborgs (probably clones). The more killed, the higher you go; if you're hit, you fall a level. The winner makes it all the way to the top to get a shot at Mr. Big (probably looks like Michael Eisner) - and gets the full free fall. Wheeee!"

It's hard to say why the Disney-Sega partnership fizzled. Eisner was notoriously tight-fisted at this point in time, and the prestige of Steven Spielberg must have been a major draw. But the repercussions of this decision would echo for years through both Sega and Disney.

Failure to LaunchSega World London opened in May 1996 and the response was... pretty bad! As with the Sega World locations in Japan, admission was a separate price than the games were, meaning once you had paid your £12 (modern US equivalent, over $30), the larger rides could cost up to £3 each. Multiply that by a family of four, and you begin to see the problem.

Throughout its life span of only three years, attaining the balance of admission to ride cost was a constant struggle, with the attraction going through phases of free admission but high cost rides and vice versa. Sega GameWorks in the US was just as expensive, with admission costing an eye-watering $20 to enter in 1997 and major attractions costing $4. Bit by bit more and more of the Sega World London building was closed off and machines were grouped closer and closer together, until the Trocadero exercised their option to cancel the lease early. All told, in three years Sega World London failed to generate even £ 3m revenue.

In May of 1996, the Saturn's early lead on the Playstation in Japan had fallen to second place. The Saturn premiered at second place in the US and never gained any market traction, partially thanks to its confusing release, and partly due to the anticipation surrounding Nintendo's N64 console. Ironically, it was an exact inversion of the situation that led to Sega's success with Sonic in 1991; the Sony Playstation was lower priced and had better games. Sony didn't even bother to compete with Sega, focusing on the launch of their mascot platformer Crash Bandicoot one week before the arrival of the Nintendo system. The N64 pushed the Saturn down to third place, and into the dustbin of history.

With Sega World London generating a fraction of its needed profits, outside Japan every single division of the company was imploding. Tom Kalinske tendered his resignation with Sega in July 1996. Hayao Nakayama resigned as CEO of Sega of Japan in 1998. Sega of America went through two more CEOs in four years, finally pulling out of the console market in January 2001 with the failure of the Dreamcast. Sega would never return to the heights it had reached in 1994.

--

And so finally there was DisneyQuest.

It's hard to say why Disney moved ahead with DisneyQuest once Sega departed. Sometimes projects just develop enough momentum that nobody really pumps the brakes, and it's possible that this is what happened with DisneyQuest.

It's possible that Eisner got really bullish on regional entertainment, although he doesn't seem to have cared all that much about any of the offerings that division of the company came up with. In fact, according to David Greising in the Chicago Tribune (Jul 18 1999), Eisner initially wanted to cancel the project. Greising reports that this occurred "four years ago", placing the theoretical date sometime in 1995. In Greising's reported version, Eisner's complaint was centered around the arcade not leveraging enough Disney IP, which makes me wonder if the initial pitch was essentially a mildly upgraded Sega World.

But it's important to know about Sega World London and to draw the direct line between it and DisneyQuest because it helps show how Disney both copied and improved on the Sega World formula. Instead of a McDonalds they had a Cheesecake Factory. Instead a fancy escalator they had a fancy elevator. Even the idea of bringing visitors up to an upper level and letting them wind down through the exhibit to the ground floor exit remained, a feature implemented exclusively due to the unique nature of the Trocadero structure... but repeated for DisneyQuest.

WDI ended up developing all of the key attractions for DisneyQuest in-house, meaning the costs for each ballooned because they were being engineered from the ground up. Had Sega and Disney moved ahead as partners, WDI could have cherry-picked through Sega's impressive catalogue for arcade attractions to retrofit, reducing development costs. Practically everything done at DisneyQuest could have been done cheaper with Sega; CyberSpace Mountain could have been built off a Sega R360. The Alien Encounter rail shooter was a specially engineered box that mimicked a Sega AS-1. Disney spent huge sums on bulky VR headsets while Sega had already developed slim, cost-optimized versions for their arcades.

Really, Mad Bazooka becoming Buzz Lightyear Astro Blasters is only the most obvious one, because nearly everything in DisneyQuest had already been engineered before by Sega.

In this theoretical scenario, Sega would have developed the game component of the experience while WDI could have focused instead on the theming and layout of the facility. I really should emphasize here for those of you who weren’t there in 1998: the rides and experiences at DisneyQuest were very impressive for their time, but I sure would have killed to see what Space Channel 5 and Shenmue-era Sega could've done with those games.

Wise or not, DisneyQuest was a go and Disney announced the formation of Disney Regional Entertainment in 1996. The division was headed up by Art Levitt, former CEO of Hard Rock Cafe, which pretty much says exactly what Eisner's goals were here.

Their first concept was Club Disney, an inexplicable attempt to copy Chuck E. Cheese and Discovery Zone. Disney was somehow not deterred by the recent bankruptcy of Discovery Zone in 1996. Jay Rasulo (!) told the Tampa Bay Times: "I would say that the customer is probably similar (to Discovery Zone's customer), a young family, but our concept is much more diverse. It's active, creative, interactive." The Times went on to interpret his vague statement by clarifying: "No ball pits are planned, for instance." But Club Disney was merely the overture; the big project was DisneyQuest.

DisneyQuest ended up opening two locations, one in Walt Disney World and the other in Chicago. The Chicago location closed after only 2 years; it wasn't making enough money to afford its downtown rent. The end of the DisneyQuest project meant that the Orlando location was cursed to a 16 year zombielike existence as bit by bit its various components broke down and were never replaced.

This gets to the heart of the real problem: the mid-90s were maybe the worst time possible for Disney to be entering the arcade business. The entire video game industry was making the leap to 3D, a transformational technological shift that would end a lot of careers in the industry. Even the established players were struggling.

Everything in DisneyQuest was dependent on novelty, not gameplay. It was fun to do things like Ride the Comix or the Alien Encounter attraction once, but I - someone who grew up on Nintendo and Sega - never once felt compelled to pay to go back into DisneyQuest, and I don't think my experience is at all unusual. If the gameplay isn't there, then the only leg a game has to stand on is the technical polish, and all of the DisneyQuest games looked embarrassingly dated by 2002. Conversely, you can put a four year old down in front of Super Mario Brothers and they can still have fun despite the fact that the game looks exactly like it comes from 1985. This is where Sega's absence hurt the most. And then there is the fact that people expected DisneyQuest to be, well, more Disney. When you tell people that Disney is opening an indoor theme park in their towns they picture Mickey Mouse, Main Street, and fireworks, not a windowless box with VR headsets. This was one of Michael Eisner’s biggest miscalculations during his tenure as Disney’s CEO. You can’t just stick the Disney name on anything and expect people to accept it at face value. The name Disney carries in-built connotations of quality and opulence. And yet he made the mistake again and again, at DisneyQuest, at California Adventure, and Disney Studios Paris, and these are ventures that the company is still paying for decades later.

And then there is the fact that people expected DisneyQuest to be, well, more Disney. When you tell people that Disney is opening an indoor theme park in their towns they picture Mickey Mouse, Main Street, and fireworks, not a windowless box with VR headsets. This was one of Michael Eisner’s biggest miscalculations during his tenure as Disney’s CEO. You can’t just stick the Disney name on anything and expect people to accept it at face value. The name Disney carries in-built connotations of quality and opulence. And yet he made the mistake again and again, at DisneyQuest, at California Adventure, and Disney Studios Paris, and these are ventures that the company is still paying for decades later.But you know, the thing is, this could have been great. Sega’s arcade installations were often called "theme parks" in the press through the 90s; the use of the term is important as it is intended to convey that Sega Joypolis is something more than an arcade. In the course of researching this article, I found myself looking again and again at the Sega attractions for Joypolis and Sega World London and saying "I'd pay to ride that", or "That looks like fun."

Fact is, Sega has continued to operate a Joypolis in Tokyo and successfully merge gameplay and attraction fun; they have an indoor roller coaster where you play a basic rhythm game while riding; it looks fun. They have a crazy indoor arena where you spin around on the end of a pendulum and shoot at screens on either end of the arc; it looks fun.

I'd give a lot to know if Disney walked away from Sega or if Sega walked away from Disney; given the self-destructive impulses reigning at both companies at the time, either seems credible. But it feels like they were both so close to pulling it off; it's easy to imagine that with costs spread between the two companies and with Sega doing what they were good at and Disney doing what they were good at, both could have come up with a concept that would not have flamed out so quickly. Sega would have continued to push the tech forward and develop new games, Disney could have focused on appealing common areas, and they both could have created viable product.

You can't tell me that one or two DisneyQuest locations wouldn't still be operating today if it had an actual indoor coaster and a version of Ghost Hunt themed around the Tower of Terror or something like that.

GameWorks Chicago in its 90s glory

GameWorks Chicago in its 90s gloryIt's not as if Sega's GameWorks venture ended up any better for them. Concurrent with the Disney installation at Epcot, Sega repeatedly announced - and then did nothing about - a partnership with Universal Studios in Los Angeles. I've held this part of the story back until now because I couldn't find anything in press clippings that made any better sense of what was going on behind the scenes, but even as Disney was hyping up Sega's presence in their projects in Orlando and New York, Universal kept promising a Sega "theme park" in Hollywood.

To me this confirms that Spielberg, not Katzenberg, was the mover behind the scenes due to Spielberg's connections to Sid Sheinberg and Universal - the Dreamworks SKG offices were on the Universal lot. The timing suggests that Sega was interested in moving into Universal's new CityWalk complex, and a Sega GameWorks was actually announced for the Florida CityWalk in 1997, but nothing ever came of this.

DreamWorks SKG pulled out of GameWorks in 2001, at a time when most of the Joypolis locations in Japan were closing. Sega GameWorks stuck it out alone in the US for another nine years before shuttering most of the locations in 2010.

Sega itself only barely survived this era. Their majority shareholder, Isao Okawa, had been funneling his personal fortune into the company to keep them afloat. Upon Okawa's death in 2001, he forgave the company's debt to him and gave the company a reported $700m worth of stock. Sega used these assets to restructure as a third-party game developer; without them, there was a very real possibility they were going to close. The Saturn and Dreamcast weren't just market failures - they basically killed Sega as it existed at the time.

Both of these eras of Disney and Sega are as discussed and obsessed-over periods of corporate chaos as you can find. Fans of video games and theme parks continue to debate and discuss them, but what fascinates me is how closely entwined these stories actually are. It's hard not to look at Eisner babies like the Disney Decade and Disney's America as obvious missed opportunities, but those were risky, weird ideas that may not have worked even had the stars aligned. But a Sega DisneyQuest, with Sega tech and Disney show unified? That one may actually be the biggest missed opportunity of all.

In the end it may have been Sega president Hayao Nakayama and his notoriously prickly personality that sank both of those ships. In 1993, when Sega was still ascendant and DisneyQuest was not yet a twinkle in the eye of Art Levitt, he sat down with the New York Times and confidently announced "Our target is Disney". You can't get into bed with the multinational media giant you want to challenge to market supremacy.

Nakayama's bravado is admirable, but the prediction made in the same article by author Andrew Pollock was more accurate. He wrote:

"Instead of becoming the Disney of the electronic age, Mr. Nakayama's Sega might just as well become the next Atari, a video game company that experienced meteoric growth on the strength of one product in the early 1980's -- only to nearly collapse when the market shifted."

--

Putting this article together was a massive undertaking. As the only writer I know of straddling both the theme park and retro gaming scenes, I had long been puzzled by the obvious links between Sega World London and DisneyQuest, and once Tom Morris provided the "missing link" in his interview on the podcast linked below, I really felt a responsibility to get the larger story on paper that both communities were perhaps unaware of. This involved synching up the stories of two massive, drama-prone corporations, and this really was only possible thanks to the amazing research of other writers who have delved deeper into the indivdual components of this story than I ever could. I stand upon the shoulders of the giants listed below:

Progress City Radio Hour: Tom Morris Interview, Part Two

The Sega Arcade Revolution by Ken Horowitz

The Ultimate History of Video Games by Steven L. Kent

Expedition Theme Park: Alien War

Disney Channel Making of Epcot's Innoventions

Dave Luty: Sega at Innoventions

Dave Luty: The History of Sega World London

Kevin Perjurer: The Failure of DisneyQuest

Norman Caruso: The Story of the 32X

Norman Caruso: Sega's Three Biggest Mistakes

Newsweek: Spielberg is the Ultimate Game Boy

SegaRetro: Sega Takes Aim at Disney's World

Coaster Studios: Sega Joypolis Review

Many thanks all.

--

If you enjoy very long, very elaborately researched articles about theme park history, you found the right site! Try starting out here, or here!

Or if you want even more, I have an entire book about Disney's Haunted Mansion, available on Amazon here!

April 9, 2021

The Mall as Disney; Disney as the Mall

"What [Disneyland] is all about is inhabitation, the human act of being somewhere where we are protected, even engaged, by a space ennobled by our presence Inhabitation is a powerful reality that architecture is supposed to be all about but more often isn't. It is a reality vividly present at Disneyland, whose own reality is so often dismissed." - Charles Moore

It doesn't take all that much looking to find them, the people who have never quite gotten over the conversion of Downtown Disney to Disney Springs. Head to the correct corners of the internet and they will be there, ready to tell you that Downtown Disney was special and unique and Disney Springs is... just a mall.

"A huge outdoor mall with too many people"

" Its like a shopping Mall with little Disney experience. You could be in a Mall anywhere."

"Downtown Disney at least felt like you were still in the "Disney Bubble" Disney Springs is just another high dollar outdoor mall like you can find in any major city."

Let's stop for a moment and unpack that idea. It's been an insult in our culture for a long time, ever since the multi-regional mega malls became successful enough to become a threat. Time was, any shopping could get done at these gigantic indoor behemoths, anchored by Sears or JC Penny, temples of commerce, social centers of their communities. Time was... never to return, for the bubble of the mall was a fairly short one and failed to survive the 1990s. Today, the United States is littered with fading and failed malls and, after two decades of attempting to reverse the trend, developers are throwing in the towel. These places are being transformed into apartment complexes, community colleges, and office buildings.

And yet the Lake Buena Vista Shopping Village, aka the Walt Disney World Village, aka the Disney Village Marketplace, aka Downtown Disney, aka Disney Springs, lives on. If it's just a mall, it has long outlived the usefulness of that insult.

Yet in another way malls do live on. There is an entire online community of people devoted to documenting these crumbling relics of the 20th century, and entire music genres devoted to evoking, through some layer of knowing despair, the cheery canned soundtracks which once filled the neon-lit malls of the cultural imagination.

Yet in another way malls do live on. There is an entire online community of people devoted to documenting these crumbling relics of the 20th century, and entire music genres devoted to evoking, through some layer of knowing despair, the cheery canned soundtracks which once filled the neon-lit malls of the cultural imagination.The mall, especially the mall of the 1980s, has graduated in its own lifetime to become a touchstone, a composite image of a time that never existed in reality. The Generation X teens who hung out there and the elder Millennial kids hopped up on cola remember the excitements and pleasures of these places in their prime, and have gone on to turn the mall into the 1980s equivalent of the 1950s diner, the chrome and neon burger palaces commemorated in films like Grease and American Graffiti.

In short, the mall is culturally important in the same way that Disneyland is, and for many of the same reasons. As temples of curated but no less real pleasures, as products of the socially programmed 1950s, and as examples of real estate development which failed in all but a few key locations, the mall is very much a twin of the Disneyland-style theme park.

--

Quick, name the most successful and influential mall in history!

What did you come up with? The Mall of America? West Edmonton? King of Prussia?

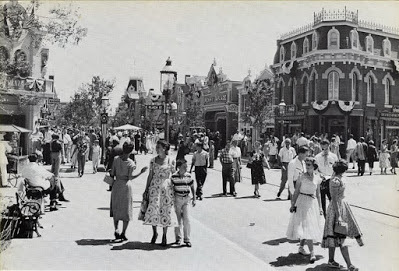

How about Main Street, U.S.A. at Disneyland?

Opening smack in the middle of other influential retail developments - Wisconsin's Valley Fair opened in March 1955 and Victor Gruen's Southdale Center in October 1956 - Main Street drank deep of the cultural times, saw a trend, and learned its secret name. A curated mix of stores and exhibits tied together with a unifying aesthetic and steeped in the kind of bleary-eyed nostalgia my generation now feels for malls themselves, Main Street has flourished while the rest have declined. It's never lost its major tenants, it has never succumbed to seediness, it continues to draw crowds, it has opened multiple new locations around the world, and it has managed to adapt to changing times without losing its essential qualities for nearly seven decades now.

Opening smack in the middle of other influential retail developments - Wisconsin's Valley Fair opened in March 1955 and Victor Gruen's Southdale Center in October 1956 - Main Street drank deep of the cultural times, saw a trend, and learned its secret name. A curated mix of stores and exhibits tied together with a unifying aesthetic and steeped in the kind of bleary-eyed nostalgia my generation now feels for malls themselves, Main Street has flourished while the rest have declined. It's never lost its major tenants, it has never succumbed to seediness, it continues to draw crowds, it has opened multiple new locations around the world, and it has managed to adapt to changing times without losing its essential qualities for nearly seven decades now.Moreover, Main Street more than any other single component of Disneyland wiped out fifty years of amusement park tradition at a stroke. Old-style amusement parks had multiple entrances, but Disneyland made you pay to get in, a new and controversial idea at the time. Main Street is such a pleasure to traverse that nobody much seems to mind that the only entrance and exit is through a mall. Indeed the entire concept that theme parks could have multiple entrances is now such a novelty that Disney has successfully monetized the concept by attaching it to other Disney owned revenue centers such as hotels.

It's little wonder that no serious critical look at Disneyland has failed to observe Main Street with a mixture of disgust and awe, the ultimate and best mall, the anchor that made the success of the rest possible. Umberto Eco wrote:

"Disneyland's Main Street seems like the first scene of a fiction whereas it is an extremely shrewd commercial reality. Main Street - like the whole city [Disneyand], for that matter - is presented as at once absolutely realistic and absolutely fantastic, and this is the advantage (in terms of artistic conception) of Disneyland over the other toy cities. The houses of Disneyland are full-sized on the ground floor, and on a two-third scale on the floor above, so they give the impression of being inhabitable (and they are) but also of belonging to a fantastic past that we can grasp with our imagination. The Main Street facades are presented to us as toy houses and invite us to enter them, but their interior is always a disguised supermarket, where you buy obsessively, believing that you are still playing."

As if recognizing the impact, in 1965, the city of Santa Monica a few miles north would permanently cordon off the north-south stretch of downtown shopping on Third Street, turning what was an organically grown strip of shops into a kind of Main Street, a kind of mall. But Disneyland, retail, and city planning go even deeper than that.

It is no coincidence that Victor Gruen was both the inventor of the enclosed shopping mall as well at the author of The Heart of Our Cities, the book Walt Disney read and adopted as his blueprint for his EPCOT city. Gruen advocated for rebuilding existing communities on the shopping center plan, which is pretty much exactly what EPCOT was going to be, with the entire downtown being an enclosed, climate controlled Gruen wonderland with a great big hotel at the center of it. After Walt's death the EPCOT city was killed pretty much immediately, but the hotel did survive. When author Anthony Harden-Guest interviewed Walt Disney World Master Planner Marvin Davis about the EPCOT project, Davis pointed to that central hotel EPCOT and said:

"The proposal first was just to build this as one of the original hotels, then later on we'd be building the balance of [the city].."

In other words that central hotel slowly morphed into the Contemporary Hotel, which is why there still is a monorail running thru it today, exactly as it would have had as part of the EPCOT City. And so it is appropriate that the Contemporary's Grand Canyon Concourse is one of the few places left in the United States to see exactly what Gruen's ideal shopping mall would have been like. It is functional, except with hotel rooms instead of apartments and offices above it (many Gruen shopping malls are intended to have office spaces). It is linked in with mass transit, offers climate controlled shopping and dining, lets in natural daylight, and dominated by public art. Any company except for Disney would have demolished the building by now.

--

The Gruen-style mall was intended to be an enclosed downtown city dropped into suburbia, but not everyone wanted that, and for a few decades there was a competing style: the shopping village. Originating in Southern California where inclement weather was less of a concern, the village model split apart the traditional Downtown into a series of charming, sometimes lightly thematically unified shops.

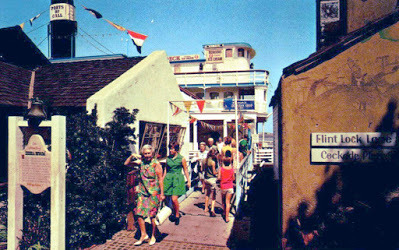

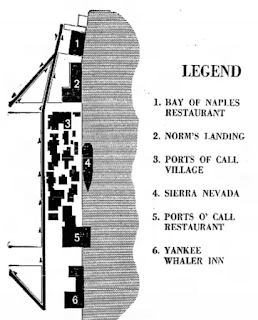

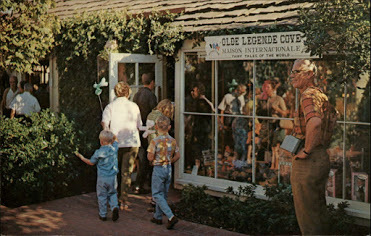

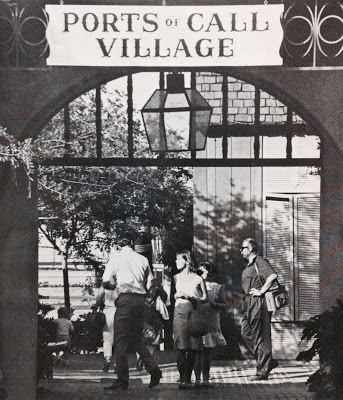

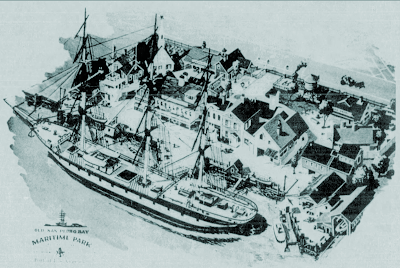

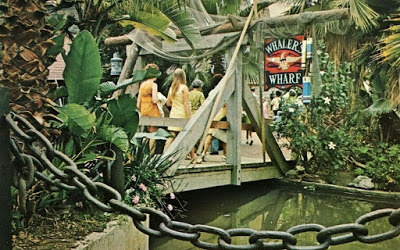

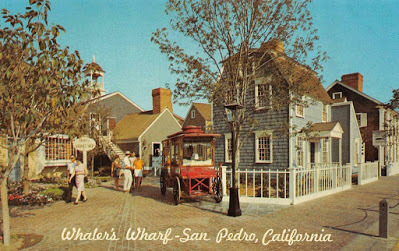

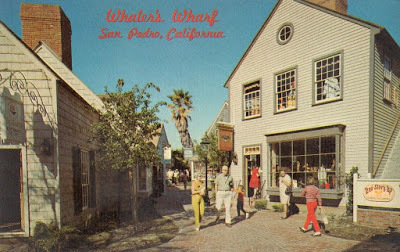

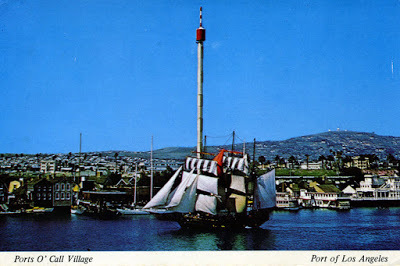

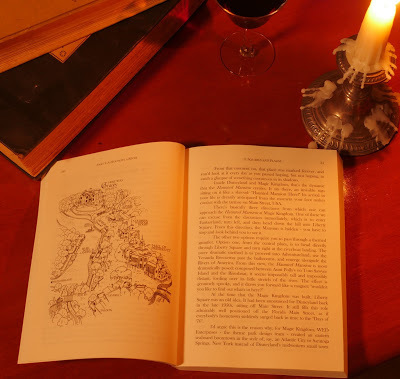

The Gruen-style mall was intended to be an enclosed downtown city dropped into suburbia, but not everyone wanted that, and for a few decades there was a competing style: the shopping village. Originating in Southern California where inclement weather was less of a concern, the village model split apart the traditional Downtown into a series of charming, sometimes lightly thematically unified shops.This was a popular option in areas where maintaining some sense of historical character was desirable; as a child in New England I knew a lot of these but didn't yet know they are part of an actual retail trend. I covered one of the earliest and most influential of these themed, landscaped malls in my post on the very surprising history of San Pedro's Ports O' Call, but through the 60s and 70s they sprouted up all over, often in areas not yet capable of supporting a fully indoor mall.

If the dream of a functional EPCOT city died with Walt Disney, it didn't entirely go away. Although Disney's claim in 1982 that their EPCOT Center park was the realization of that idea was spurious in the extreme, some of the ground work done for that project did end up in the Vacation Kingdom in 1971, including a mass transit system, hidden underground areas for utility work, a modern hotel with a monorail running through it, and an automated trash disposal system. But if Disney had no intention (really no interest) in actually building that city, they did think they could build something else, something pretty close to another kind of planned city where they had recently been spending a lot of time.

That was Bayhill, Florida, a fairly early example of the now-common golf retirement communities built throughout the Sun Belt. By the late 60s Bayhill had been purchased outright by Arnold Palmer, and the Disney executive team was spending a lot of time in the ranch houses, clubhouse and golf links alongside Lake Tibet. Their property had a lot of lakes, too...

I go into the history of Lake Buena Vista, Disney's 70s timeshare community that never quite got off the ground, here. But suffice to say, they tried again and again for nearly a decade to copy what they saw up the street in Bayhill and never quite managed to get anyone interested until Eisner took over the company in 1984 and all of those ambitions went away. But they did build a "downtown" for their planned community, and they based it pretty nakedly on Ports O' Call Village. Though much more obviously compromised in original effect than either Main Street or the Grand Canyon Concourse, much of the Lake Buena Vista Shopping Village remains intact today.

Yet culture changed as it always must. Gruen's enclosed malls returned in the late 70s, giving birth to the 80s mall today enshrined in myth and legend. Families fled urban centers for the suburbs. Where adults saw peace and security, their children - Generation X - saw stifling conformity. These kids fled the suburbs to the more open artificiality of the youth culture of regional shopping malls. This powerful story has totally pushed the shopping villages, built by and for our parent's parents' leisure, off the map entirely. But go looking in the right places and they're there still, and Disney's example was part of a trend like many others.

--

Disney Parks retail developments mostly slept out the 80s, the boom years for malls. The nearest example is the Old Port Royale at Caribbean Beach, the resort's key amenity cluster separated, like the Contemporary Resort, from it's check-in area. Since redone in a classier style, the original Centertown area was pure 80s whimsical mall architecture, with faux Caribbean facades lining an entirely unconvincing "street".

Disney's mall for the 80s was Pleasure Island, a kind of postmodern extension of the Lake Buena Vista Shopping Village done up in the then-popular trend of industrial chic. Starting especially in the late 80s and early 90s, retail began to merge the Gruen-style big box with the quaint shopping village into what we now recognize as "lifestyle centers", anchored by large chain restaurants.

Pleasure Island takes the existing lifestyle center trend and feeds it through the meat grinder of the 80s trend of "adaptive reuse". Adaptive reuse is currently very hot in the United States, but the current trend is for minimal use of exiting stone and wood whereas in the 1980s these crumbling post-industrial buildings were being turned into gonzo neon wonderlands. The influential example here is Pier 39 in San Fransisco, but the trend was everywhere through the era; remember The Old Spaghetti Factory, with its faux streetcars themed to wherever the restaurant happened to get built? Much like that chain restaurant, the industrial chic history of Pleasure Island was entirely imagined, with disused shipping facilities becoming roller arenas and baby back ribs being sold in restaurants themed to warehouses which have exploded.

But lifestyle centers were just getting started. The gonzo theming of these high-profile big city chic dining experiences eventually trickled down to the middle class, with the rise of the chain themed restaurant in the early 90s that was kicked off by Hard Rock Cafe. Planet Hollywood made the trend mainstream, but it had sprouted like crab grass in any place that was ripe with tourists ready to plunk down their fat Clinton-era dollars on novelty. Steven Spielberg opened a sub shop that looked like the inside of a submarine, The All-Stars Cafe and ESPN attempted to copy Planet Hollywood but with sports, Rainforest Cafes created a boom economy in walk-under aquarium and gorilla animatronics, and even David Copperfield attempted to get in on the action. Some small restaurants even re-christened themselves "Road Kill Cafe" and re-named all of their menu items with gross puns on local wildlife extinguished on the nearby highway. In the white-hot days of POGs and Gateway PCs, you had to have a gimmick or go home.

Perhaps the enduring temple of postmodern design, themed lifestyle centers, and mega-chain novelty restaurants remains Universal CityWalk in Los Angeles. Opening in 1993, even to the viewer jaded by a thousand listless outdoor malls, CityWalk remains startling and enlivening. Anchored by a movie theater and concert venue, it's one of the most exciting public spaces in Los Angeles, a constantly surprising winding journey that ends with the entrance to one of the best theme parks in the country amidst splashing fountains and bustling outdoor life. Disney, of course, needed a clone of this too. And so was born Disney WestSide, with the existing Pleasure Island AMC and Planet Hollywood now joined by a raft of novelty shops and restaurants, with the concert venue becoming a Cirque De Soleil. At this point the Village Marketplace (formerly Shopping Village), Pleasure Island, and the new West Side became re-christened Downtown Disney, introducing twenty years of logistical and traffic nightmares which have only just now been solved. Victor Gruen would not have approved.

Perhaps the enduring temple of postmodern design, themed lifestyle centers, and mega-chain novelty restaurants remains Universal CityWalk in Los Angeles. Opening in 1993, even to the viewer jaded by a thousand listless outdoor malls, CityWalk remains startling and enlivening. Anchored by a movie theater and concert venue, it's one of the most exciting public spaces in Los Angeles, a constantly surprising winding journey that ends with the entrance to one of the best theme parks in the country amidst splashing fountains and bustling outdoor life. Disney, of course, needed a clone of this too. And so was born Disney WestSide, with the existing Pleasure Island AMC and Planet Hollywood now joined by a raft of novelty shops and restaurants, with the concert venue becoming a Cirque De Soleil. At this point the Village Marketplace (formerly Shopping Village), Pleasure Island, and the new West Side became re-christened Downtown Disney, introducing twenty years of logistical and traffic nightmares which have only just now been solved. Victor Gruen would not have approved.Nobody has ever quite replicated the effect of that original CityWalk - including Universal - but the West Side is one of the weakest imitations around, a dull strip of stucco with a constantly rotating cast of uninspiring stores. In Los Angeles, home of some of the finest shopping malls around, the subsequent Downtown Disney built outside Disneyland may not be all that interesting, but it's leaps and bounds above West Side, which is now 22 years old and has somehow never quite found a reason to lure tourists very deep into its concrete canyon.

--

The other trend which totally changed the American landscape in the 90s was the arrival of the big box. Big box stores were nothing new, of course - as discount, suburban outgrowths of big city department stores, they had been a force in the economy since the 1970s and the ascendency of K-Mart. But the 90s were right smack at the highest ebb of the effects of the white flight to the suburbs that had decimated American downtowns and also, crucially, an era when the huge regional shopping malls were starting to decline.

General changing tastes and concerns over those lawless teenagers who were spending so much time at the mall were causing malls to rethink their strategy and renovate themselves into sterile white environments without any of those planters, fountains, and public art sculptures designed to encourage shoppers to linger - open floor space in malls would become home to endless rows of kiosks selling cheap tat and aggressive merchants that encouraged shoppers to keep walking. This deadly combination would eventually doom the mall and push shoppers out of the mall and into the big boxes that dominate shopping life today.

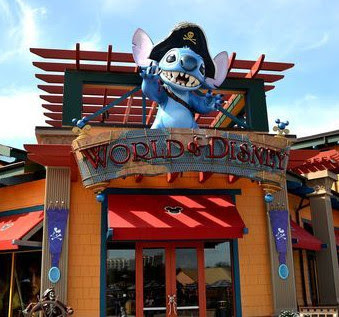

In 1995, a cluster of shops on the south side of the Disney Village Marketplace once home to the sprawling chalet-style Christmas Shop would be pulled down. Taking its place would be a new store, World of Disney, described in panting hyperbole at the time as the "largest Disney merchandise outlet in the world". As long as a football field! Nearly 6,000 square feet! A jumbotron showing Disney movies! Buy buy buy!

In 1995, a cluster of shops on the south side of the Disney Village Marketplace once home to the sprawling chalet-style Christmas Shop would be pulled down. Taking its place would be a new store, World of Disney, described in panting hyperbole at the time as the "largest Disney merchandise outlet in the world". As long as a football field! Nearly 6,000 square feet! A jumbotron showing Disney movies! Buy buy buy!Of course, the entire concept of the "world's largest Disney store" is an absurdity because Walt Disney World itself was already just that, but the ruse worked and World of Disney has remained in demand despite selling pretty much the same stuff found everywhere else at Disney. Additional locations opened in Anaheim and Shanghai, and the Disney Store on Times Square was even briefly rebranded as a World of Disney for about four years.

Everything about World of Disney, from its intentionally confusing layout, division into departments, and endless rows of cashiers and chain-branded concept reveals it to be essentially Disney's Target, an all in one stop for American accustomed to buying everything under one roof. It's an odd and revealing facet of Michael Eisner's leadership that he decided that Disney must have a chain of big boxes too, and it worked - with the parking lots stretching out into infinity.

--

Directly down the street from the Disney Studio in Burbank is a massive lifestyle center called The Americana at Brand. It sits across from the Glendale Galleria, one of the earliest and most impressively sprawling covered malls in the region. There is nothing in particular to do at The Americana, but it is none-the-less constantly packed, because it's a pleasant public space in a city that's nothing but streets. There's a red line street car that goes around the small complex in a loop, a few chain restaurants and a movie theater. There's also a Bellagio-style fountain show, and at Christmastime, it "snows" inside the courtyard, just like at Disneyland. When I lived in LA, I used to go there about once a week to sit on the lawn watching the fountains go and eat a crepe. The upper levels are all offices and apartments. It is, in fact, almost exactly what Victor Gruen wanted his shopping malls to be, minus the mass transit hub radiating outward.