Michael J. Sullivan's Blog, page 89

August 21, 2011

Writing Advice 10 — Dialog

Dialog is one of the big three tools a novelist uses to tell a story, the other two being description and reflection. Given that this is one of the three pillars, this will be a longer than normal post, and I will still be hard-pressed to get cover everything.

Some folks find dialog easy to write, others have trouble. What that usually means is that a writer is having difficulty making the conversation sound real, but honestly that is advanced level dialog, and this is still a basics class. So we are going to be going over the basics, because it is surprising how often new writers don't know them.

Dialog is when a character speaks. While this seems obvious, there are two kinds: External and Internal. External is the one most people think of. It is when a character opens their mouths and speaks. Before I get into the nuances, let's go over the basic structure because I've found a lot of writers don't know how to physically construct dialog on a page. This is something I'm often baffled by because it is demonstrated in just about every novel.

Dialog consists of two parts, the communication and the tag. The tag is the comment that designates who did the speaking like: Bill said.

Dialog starts with a (") and ends with a (") Okay so most people know that much, but what comes next they appear to have a huge problem with: Every time a new character begins to speak you create a new paragraph.

"I said no!" Bobby shouted."I don't care!" Jane shouted back.

Not…

"I said no!" Bobby shouted. "I don't care!" Jane shouted back.

I realize that there are some successful books that don't follow this rule. The Road by Cormac McCarthy doesn't use punctuation either. It is my opinion that both practices are wrong. (And if you've read my post on Grammar Nazis, you know that I think everything concerning the "rules" of writing and English, are opinions of someone. It doesn't mean I'm right, and it doesn't mean I'm wrong.) I considered these practices wrong because these techniques impede the clarity of the message, and as an author, anything that makes something harder for a reader to read, I'm against.

Even in the very simple case above, a lazy reader might think Bobby was the one who shouted "I don't care." But the problem becomes far more devastating as the writing grows more complex such as using action tags in place of dialog tags.

"I said no!" Bobby opened the door. "I don't care!" Jane had had enough.

In this case you really have no idea who said what. Bobby could have said both lines, or neither. Look at how the meaning changes when broken differently.

"I said no!" Bobby opened the door. "I don't care!" Jane had had enough.

"I said no!" Bobby opened the door. "I don't care!" Jane had had enough.

"I said no!" Bobby opened the door. "I don't care!" Jane had had enough.

Paragraph breaking in dialog is a huge tool in helping the reader understand what is going on.

Let's take a closer look at tags.

He said, is a dialog tag. It is properly written: "I love you," he said. Note the comma and the lower case H on he.

He laughed, is an action tag. Rather than directly stating the obvious, an action tag describes what immediately follows the dialog and so long as it is in the same paragraph, it indicates by association, who just spoke. "I know, I know." Bobby laughed. Note the period at the end of the know and the capital H on he. He laughed is a commonly misdiagnosed tag. New writers frequently think it is a dialog tag and write: "I know, I know," he laughed. Only people can't laugh words. And while you can spit, you can't spit and talk at the same time. You can hiss words, but only if they end in an S. You can reply, joke, comment, explain, mumble, whisper, shout, and yell, but you can't choke, laugh, smile, frown, or sigh a line of text. The difference is designated by the use of the period, verses the comma at the end of the speech.

Now while tags are necessary to know who is speaking, good writing limits the number of tags. Reading something like this is annoying:

"Who was that?" Bobby asked. "Who was who?" Jane replied."At the door just now." Bobby said. "Who was it?""Oh, that?" Jane said. "Nobody.""Really?" Bobby asked.

Not only is it annoying it is also unnecessary. It could just as easily have been written:

"Who was that?" Bobby asked. "Who was who?" Jane replied."At the door just now. Who was it?""Oh, that? Nobody.""Really?"

Using only two tags in five lines of speech, how can a reader know who's speaking? By using the new-paragraph-per-new-speaker technique. Can this be done if there are more than two people in the scene? Yes, so long as only two people are doing the talking. The reader assumes that the person speaking is the person who had spoken the last line of opposition. There is a limit however, because after about five lines readers tend to forget who's who. So to remind them you need to drop in an indicator, either in the dialog itself, or an action tag, or a dialog tag.

"Who was that?" Bobby asked. "Who was who?" Jane replied."At the door just now. Who was it?""Oh, that? Nobody.""Really?"Jane's heart was racing. "Just forget about it, okay?"

Instead of using the action tag: "Jane's heart was racing," You could also designate the speaker via the dialog by writing:

"Are you jealous because he's a man and you're afraid I might run off with him?"

Now assuming Jane has been established as a heterosexual female, this line of dialog can replace the need for a tag because the reader knows Bobby wouldn't say this.

Eliminating tags makes for a cleaner read, but sometimes when dealing with three or more characters all talking, you can only get so far with alternating lines, and using action tags can interrupt the flow of a conversation and kill a rising tension, or slow an exciting moment. Then it is best to just drop in a dialog tag to keep things understandable. When this happens, using said, replied, and asked, are your best bets. Anything flashier tends to stick out in a bad way and will stop the reader. I do tend to throw in an explained or commented from time to time just because I've used the others already and don't want to repeat the same words in close proximity, but keeping tags as simple as possible is important. And try never to use an adverb as part of a dialog tag.

"I don't like you," she said furiously.

Adverbs like this are just another form of Telling. This line is telling the reader that the speaker is upset. But the same can be shown by just improving the dialog to:

"I hate you!"

This doesn't need an adverb to explain how the speaker feels.

Another aspect of dialog that people frequently get confused about are the uses of em dashes and ellipses. Em Dashes are used to indicate an abrupt pause in dialog while ellipses indicate a trailing off.

"You know what you are? I'll tell you what you are! You're so—so…oh I don't know what, but you are!"

Here the em dash indicates that brief pause created by a stutter in speech, whereas the ellipse indicates that a character is taking a few seconds to think, to trail off in thought. Em dashs at the end of a sentence indicate a person has either been interrupted or has self-edited, while an ellipse shows they just never bothered to finish their thought

"I think—""We don't care what you think!"

"I think…""Well? What do you think?"

All this is done without having to say:

"I think—" he was interrupted."We don't care what you think!"

"I think…" he trailed off."Well? What do you think?"

These tags are redundant.

Now getting back to the Internal dialog, this is when a character uses direct thought—usually indicated by italics and a shift to First Person, if writing in Third. If you're already in First then everything is in direct thought already so no italic is needed.

He walked to the door and closed it. Why do I keep putting myself through this?

In this way the writer jumps directly into the character's head and we hear his thoughts written as dialog. This is not contained in quotes so it needs italics to set it off as different from the rest of the story.

Usually it is considered bad grammar to use contractions outside of dialog as contraction's only purpose is to mimic speech patterns. Therefore it is improper usage to write:

Bobby came home that night and made himself dinner because he didn't think anyone else would.

The word didn't in this sentence should not be contracted because no one is speaking it.

The only other time contractions can be properly used outside of spoken dialog is in direct thought. Since direct thought is an internal dialog, the character is actually speaking to themselves in their head, and when people do this, they use contractions. So the line can be written:

Bobby came home that night and thought, I'll have to make myself dinner because no one's gonna make it for me.

Now if a book is written in first person, the whole thing is direct thought, so contractions are used all over the place. Once again, this is one of those rule-things, and in art, rules are there to be broken, and novel writing is as much art as it is craft. Zadie Smith is one of those writers who breaks most of the rules. She writes in third person with a shifting PoV and a prose style that is very conversational—as such she feels the need to use contractions to form the tone of her style. This is her Voice (something I will talk about later.) But again, rather than trying to sprint for the gold in the Olympics one ought to start by getting the hang of crawling first. So you might want to master playing by the rules before breaking them, because the rules were invented for a purpose—they make it easier for the reader to understand what it is you are trying to tell them.

There is also indirect thought, which is what happens in Third Person Close. This is sort of a false internal dialog:

This was not just some fight—not a fight at all. She planned this. That whole thing about her parents cornering her for a surprise talk about college was a lie. She was the one who plotted the ambush, a clever bushwhack at a friendly pizzeria where she could walk out when it got uncomfortable. He wondered if her parents were even involved. The whole story might have been an excuse.

This isn't direct thought, it is simply the narrator describing up close and personal what is going on in the character's head without actually becoming that character. The result is reflective thought that is heavily colored by what could be an unreliable narrator, or at least one who is only presenting a narrow viewpoint at that moment. So it isn't really dialog and shouldn't be handled as such.

Now that we've covered the mechanics let's look at another common problem with dialog. This is another of those diseases that stem from Telling rather than Showing. The problem arises when a writer wants to give information to the reader and to avoid exposition in narrative, they think they can get away with it if they disguise it as dialog.

"What's wrong, honey?"

"Oh it's Barbara. You know, my friend that I've known since high school, who lives next door and is always over here? The one with the dark hair and emerald green eyes, who is more attractive than I am so that I am always jealous of her whenever you look her way?"

"Oh, yeah. What about her?"

I am over emphasizing, but you get the idea. The problem can also be as simple as having one character speak to another using their name. This is a cheating way to avoid tagging the dialog and is a form of Telling that should be avoided.

"I don't know, Bob, this isn't coming out so good.""You know what, Jane, I think you're right."

No one speaks this way except slick sales people who were taught in sales school that if you repeat someone's name to them, they subconsciously think you are friendlier.

When you think about it even the, he said, tag is outright Telling, but it is a more accepted form of Telling, but also the reason dialog tags should be avoided when possible.

I was recently re-reading an old manuscript of mine and noticed how often my dialog was being used to tell the story rather than present what the characters would actually say. Two scientists would meet to discuss theories that they both already knew, with lines like: "As you know professor Bill…" which is absurd, because if he knew why would you reminded him of what he knows. So it is important to restrict dialog to only what a person would actually say in a given situation. Even something as simple as: "Bill, look out for that falling rock!" is wrong. No one would say all that. Rather, they would just say: "Look out!"

Another problem to avoid is to realize that inside quotes you can do anything. There are no rules of grammar or spelling. Inside quotes anything goes. This is because inside quotes, thanks to Mark Twain, we are now free to mimic how people actually speak, rather than how they should speak. So not only can you use contractions, you should. And you should rarely allow characters to speak in complete sentences, because few people ever do.

If you want to learn how people really talk, try going to a coffee shop with a laptop. Sit down and type exactly what you overhear from neighboring tables. You'll get a lot of: "Ah…and—ah. You know?" These are probably the most used words in the English language. While this is accurate to real speech, as a writer you don't really want to write this because it is just as irritating to read as it is to listen to. So as a writer writing dialog you want to present the concept of realism, without actually writing the way people actually talk. This is done with broken sentences: "I can't—I don't know—I just can't come out and just say it like that. Damn. Okay maybe." Most of the sentences in the dialog above are grammatically incomplete, and yet they present the haphazard sense of genuine dialog.

Dialog also can be a huge tool in characterization. How a person speaks will indicate who is speaking even before the reader reaches a tag. The obvious way is to use slang, or phonetic dialects: "Ya'll gunna, be thar?" The problem with this is that it makes the reader have to stop and decipher the language, and as I've said, I hate anything that makes reading harder for the reader. You can do the same sort of thing without the phonetics and just dropping words. Instead of "Is everyone going to be there?" you can still write, "Everyone gonna come?" and it doesn't stop you like the phonetics, but still gives that same change in tone.

One of the tricks I used in the Riyira Revelations was to utilize contractions in speech with the lower classes and rarely use it with the nobility—particularly when they were speaking publically or trying to intimidate someone. Not using contractions in speech causes the dialog to sound stiff and formal—just the way I wanted my nobility to sound. The lower the class, the lower the education level, the more contractions and dropped words.

Then of course there are just favorite words or phrases. Saldur always uses the phrase "my dear" when speaking to women. Captain Seward had a propensity to curse deities with phrases like: "Good god!", and "Good Maribor!" as he was a bombastic character. Some use large vocabularies, and others very small ones. Some swear, others never do. In this way you can Show characterization rather than Telling it to the reader. You don't have to write that a character is sophisticated and refined, just have them speak that way. After a while you will notice that each of your characters have specific dialog idiosyncrasies that are part of their their make up. Edith Mon never used the word "your." Mince constantly uses the phrase, "By Mar!"

Dialog is an extremely powerful tool, and one of the best because it speeds up the pace, and if done correctly, can solve all kinds of problems with characterization, and description, without resorting to Telling.

Next week I'll touch on the second primary tool of writing—Description, which will pretty much conclude the Basics of Writing. That's the bell, and remember, no running in the halls.

Published on August 21, 2011 10:06

August 18, 2011

I Talked With Moses

Moses Siregar III of Adventures in SciFi Publishing that is, what did you think?

It was about the time that news of the deal with Orbit was becoming public, and Moses invited me to do an audio interview. We had a good time, but since he did not air the interview for several months afterward, I forgot about it.

Today I noticed a thread comment on the SFFWorld forum that had a link to the interview. (Posted July 1.) For kicks and giggles, I listened. It had been so long I forgot what was discussed and found myself completely transfixed with the discussion. Usually I cringe listening to myself speak, but I thought I had done fairly well.

In the broadcast I discuss everything from the origins of the word Riyria, to what the future holds for Royce and Hadrian and my writing career.

So if you are interested in hearing me speak, or if you just have an hour to kill—yeah it lasted an hour, can you believe that—try this link and look for the little speaker icon below the books.

It was about the time that news of the deal with Orbit was becoming public, and Moses invited me to do an audio interview. We had a good time, but since he did not air the interview for several months afterward, I forgot about it.

Today I noticed a thread comment on the SFFWorld forum that had a link to the interview. (Posted July 1.) For kicks and giggles, I listened. It had been so long I forgot what was discussed and found myself completely transfixed with the discussion. Usually I cringe listening to myself speak, but I thought I had done fairly well.

In the broadcast I discuss everything from the origins of the word Riyria, to what the future holds for Royce and Hadrian and my writing career.

So if you are interested in hearing me speak, or if you just have an hour to kill—yeah it lasted an hour, can you believe that—try this link and look for the little speaker icon below the books.

Published on August 18, 2011 08:52

August 14, 2011

Writing Advice 9 — Pacing

Pacing is the speed of the events that take place in the story, but it really is a lot more than that and runs deep into the very sentence structure of the novel.

Holding the story out at a distance so that most of the detail is obscured you might see a pattern to the events, the high exciting points, and low duller points. In this very general scope, it would not be the best choice to have all the action pressed together at the end of the book with nothing in the front but character and setting development. This creates an unbalanced plot that can cause readers to get a false impression of your story. Someone who wants an exciting book might stop reading before they get to the action, and those that want a more thoughtful story might be upset when the actions blasts off.

A story doesn't need to be evenly spaced—in fact you will want to avoid a consistent pattern. Usually it begins with a bang, then relaxes a bit, allowing characters some development time—which is hard to do during action scenes (why, I will explain in a minute)—then there will be a spike of action, then a slow build of events, then the drop to the anti-climax and the rise to the climax and then the resolution. This is a very general pattern and can be varied dramatically, but the idea is to not create deserts and floods but to keep the pacing running in a more enjoyable range. It is also important to vary the pace of heart pounding scenes with reflective character development scenes. Everyone likes variety.

I remember when I first saw the original Star Wars I thought it was a great film, but the one complaint I had was that it felt too rushed. I wanted a little pause after the characters escaped the Death Star, I wanted to learn more about Leia and Han, and the universe in general, but things just kept flying at hyperspace speeds. As a viewer I didn't feel I had time to become fully immersed into the world, to get to know the characters or reflect on the repercussions of the events that had already transpired.

Having a varying pace in a story creates a sense of perceived depth through variation. The slower sections provide footholds and dividers, allowing the reader to mentally partition off areas of the book. Taking Tolkien as example again, the Council of Elrond can be seen as the division point in the first book of the trilogy. Everything before is of one tone, while what comes after is a bit different. The council also provides a moment to take stock and breathe, before diving into the adventure again. Such an oscillating pattern creates hills and valleys to the landscape of the story that can be looked back on as distance, generating the idea of time passed, miles traveled.

A story running too fast, screams by in a blur. Events are hard to recall, and the sense of depth that helps provide a story with weight and believability, just isn't there. At the same time you don't want a story that drags. Too much straight description will weigh your story so much it will drag it to the bottom and drown it. Description should facilitate the story not dominate it. You don't want the reader feeling blind, or deaf and you want them to know where they are and when they are. And if there is something really interesting and unusual, then yes, take the time to describe it, but nothing is needed beyond this. Extra descriptions added to create a greater sense of place, or color, or mood, usually just drag a scene.

I recently set a scene in a coffee shop. I actually went to one and sat down and for hours described what the place looked like and what was happening. I later used this as background for the scene. I had way more than I needed, and as a result I used more than was necessary. A lot of it was great stuff that I was disappointed to cut, but the pacing was being crippled by the added descriptions. The story went from an exciting thriller to an essay on coffee shops and the people who visit them.

You should also remember that while the event-pace should vary, the literary-pace should remain consistent. Literary-pace here meaning "style." Clearly there is a very different pace between a Dickens novel and one by Hemingway, but it is more style than event-pacing. More things might happen in a Dickens novel than in a Hemingway book, but the speed might feel faster in the Hemingway due to the style. If you are writing in a thick descriptive prose, stay that way. If you are writing light, don't slip into long-winded, flowery wording. Stay focused and cut those clever sentences when they clash with your style.

This leads us to a more detailed look at pacing.

Zooming in it needs to be noted that there is a speed to the words themselves. Depending on how a sentence is constructed, it has a sound, a rhythm. When added to others, words become notes, sentences bars, and paragraphs, melodies. All together it creates a music. And just as music the tempo can be varied to create tension, action, or calm.

1. The man entered the convenience store and walking to the back, took a gallon of milk out of the fridge, and then ran away with it.

2. The man entered the store. He grabbed a gallon of milk from the fridge. He ran.

3. The man entered, grabbed a gallon of milk from the fridge, and ran.

The idea in all three of these are the same. The pacings are different. Why? Obviously more words are used in the first. More importantly, it is a long compound sentence. Number 2 is what writers are often told is a good solution to creating an action pace: short sentences. This creates a staccato sound, a harsh rasping sound that jerks the reader, but I found this is nowhere near as fast as the comma series sentence shown in number 3. For where a period halts the reader, the comma causes them to only slow down a step. It just feels faster.

In scenes where you want to depict fast action, rip through it with commas, and less conjunctions. Condense the ideas and leave out the descriptions. Include only what is necessary and let nothing else get in the way.

Getting back to that promised explanation of why it is hard to do character development in action scenes—this is why. In the middle of a fight, or a chase, if you pause to provide a moment where the character is reflecting on their life, or interpreting the world around them, not only will it kill the excitement of the scene, it will appear false. No one notices what's playing on the jukebox when in a bar fight. All mental concentration is constricted with laser focus on specific details and the mind has no time to reflect or ponder or muse. This is in effect the same as one sees in a movie or tv show when the editing is tight, fast, and jerky. Sure it is hard to follow, sure it's even annoying, but it does impart a visceral sense of threat, confusion, and action. Nothing at all might be happening on the screen—a guy might be sitting on a park bench feeding pigeons, but the editing and camera movement alone will put you on the edge of your seat and start your heart pounding merely by the suggestion of intensity. The same is done with words. Short. Fast. Abrupt. Ideas flying, racing, pummeling relentlessly. It is the sound of a drum roll, the sharp rapid strings in the background of a horror film. The reader has no conscious idea why the scene is so exciting—but it is.

But don't write like this all the time. Short simple sentences are annoying in large doses. In fact, when dealing with rhythms and sounds, you'll want to vary the lengths and speeds in general, but use more compound sentences in quiet moments and shorter sentences in action scenes. Learning to "hear" the music the words make is a skill that needs to be acquired through experience. Reading your own stuff aloud helps. Hearing someone else read your words to you, works even better. Then you can hear when you are "running hot" or "dragging."

This hot and cold aspect relates to the balance between dialog/description/reflection. Using any one too much will cause the story to run hot or cold. In reading your own work, you should be able to see when you have been using a lot of description, or too much reflection or dialog. The pace of the story stagnates at one speed.

Often times when I write dialog I will forgo any description because I am focusing on the conversation. Later I go back and add in the descriptions and gestures, and tags. I'll note when I have written pages of dialog and realize, the story is running "dialog hot" and needs to be cooled down with some description. I'll search for the idea pause in the dialog and insert something—anything. I was recently writing a scene of two people talking on a bus. Not much happens at night on a non-stop bus. I had already described the traffic outside and what everyone else was doing and the interior of the vehicle. Still I needed a description break. I arbitrarily made a woman get up and go the bathroom at the back of the bus passing the characters and causing them to pause in their conversation as she went by. This event had no purpose in the story except to help ground the reader in the environment and break up the flood of heavy dialog. That said you also don't want to break into a smoothly flowing dialog with annoying breaks that kill the tension, or excitement, so you need to know when to insert and when to let it run hot.

That's the bell. Next week: Dialog. No running in the halls.

Published on August 14, 2011 09:54

August 11, 2011

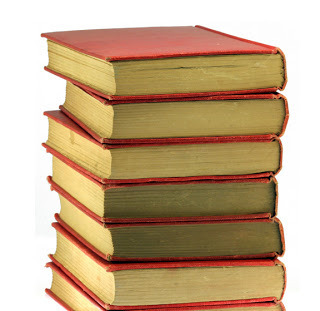

No, Really, I Have a Spine

In a previous comment it was mentioned that there was no reference on the Orbit UK cover indicating that the books were part of a series. This was a huge problem with the original release of Crown as AMI refused to have any indication on the book that it was part of a series. They were concerned that no one would buy it until all the books had been released. This was a real fear as I know several of you who refused to start the series until all the books were out...or at least supposed to be out. Although some of you actually bought the books and left them unread. Talk about faith.

As a result of the AMI release of Crown I suspect there are a good number of folks out there that have no idea Avempartha exists. That's not likely to happen this time as each book has a sample of the next book inside, and as you can see, the volume is clearly noted on the spine.

It would also make a pretty good bookmark as well, don't you think?

And as you can see, the book will have a sizable weight, making it possible to dodge the slings and arrows of, "the book is too darn short!"

Twice the book for less money than the originals, not a bad deal.

As a result of the AMI release of Crown I suspect there are a good number of folks out there that have no idea Avempartha exists. That's not likely to happen this time as each book has a sample of the next book inside, and as you can see, the volume is clearly noted on the spine.

It would also make a pretty good bookmark as well, don't you think?

And as you can see, the book will have a sizable weight, making it possible to dodge the slings and arrows of, "the book is too darn short!"

Twice the book for less money than the originals, not a bad deal.

Published on August 11, 2011 07:15

August 10, 2011

UK Covers

The Riyria Revelations is also being released by Orbit UK. They have their own cover designs that are a variation on the US ones, only a bit more up close and personal. And of course they also have to add all those extra Us, as in "favour," and change all the "gray"s to "grey." As kid, I always wondered why Tolkien was such a bad speller.

Published on August 10, 2011 08:15

August 8, 2011

Guest Blog Quid Pro Quo

Mr. Sprunk, my first guest poster has graciously invited me to litter his blog with my words. I wrote a little ditty in answer to the frequent question: Where Do You Get Your Ideas?

So click over and take a gander to see the answer. And be friendly to Mr. Sprunk and leave a comment or two.

So click over and take a gander to see the answer. And be friendly to Mr. Sprunk and leave a comment or two.

Published on August 08, 2011 09:26

August 7, 2011

Writing Advice 8 — Mini Stories

I have a friend who exclusively writes short stories. I tried to convince him to try a novel, but he insisted he wasn't comfortable with that form. I told him that writing a novel was just putting together a series of short stories. He didn't accept that. I think the issue was in the definition of "short story." Most short story writers view it as a medium very different from a novel. For example a short story begins at the height of the event and captures just that, so a novel can't be the culmination of what would be a series of climaxes, and in this respect I agree, but that's not what I meant. So, in order to avoid this confusion, I've played a game of semantics and have redefined the statement as: A novel is a series of Mini Stories that comprise a larger one.

So what is a mini story and how does it differ from a short story?

A mini story has a beginning middle and an end, but it doesn't have to be the apex. There doesn't have to be a character arc, twist, or reveal. It merely needs to put forth an idea, discuss it and then resolve it. Just about everyone of my blog posts are mini stories, but I wouldn't call them short stories. They begin with a premise, discuss it, and often conclude with a new way of looking at the beginning thus creating a circular concept that concludes as a whole idea.

In the post Genesis I describe how I started writing. The post begins when I found a neighbor's typewriter and typed the line: "It was a dark and stormy night." I was fascinated by this tool and what it allowed me to do. I wasn't allowed to play any further with the typewriter and this aspect of the post is abandoned as I go on to talk about how I learned to like stories through reading The Lord of the Rings, but when I was done with it I wanted more and could not find anything else like it. I was depressed. Now up to this point this "story" is still open-ended. It is what I call a linear plot, meaning that it starts at point A and moves straight to point B. It is a mere series of events, not a story. What made it a story is that in the end, my boredom led me to complain to my mother and she taught me a lesson by insisting I clean out the front closet. There I found my older sister's old typewriter, and the post concludes with the line: "I never finished cleaning out the closet." In this way, the series of events turn back on themselves and connects to the start forming a circle and a story. The end explains the beginning and gives reason for the middle.

Not everyone sees a story in this way. I have read many short stories, and seen a few movies, that are just a series of events that start at a random point and end at a random point. Personally I don't recognize these as stories. Stories for me must have a point. If you are at dinner and say, "Oh, let me tell you what happened at work today." Those with you expect they are about to hear something with a point, rather than say… "I got up, got in the car, drove to work, did stuff, and then came home." If you did, I think those at the table might look at you puzzled and even ask, "Yeah, so?" Stories need a setup and a payoff to hold them together as a unit, otherwise they are just random events told in order.

How does this apply to writing a novel?

Let's look at The Lord of the Rings again. The story is of Frodo taking the ring to Mordor, but it is made up of dozens of smaller stories. The first being the Long Expected Party, a small story of the coming birthday bash for Bilbo. There is mystery, foreshadowing and then the big reveal and even a nice little epilogue where Gandalf catches him before he sneaks out of Hobbiton. Then there is the story where Gandalf tells the history of the One Ring, and the tale of Frodo's trip to Cricket Hollow. The larger novel is broken down into much smaller mini stories. In this way, chapters can be small stories inside a novel. What this does is provide the reader with a constant diet of interest. Most readers can't consume a whole novel in an hour. As such, the reward or even the anticipation of a reward is too far off to be gripping. What a reader wants is to be consistently rewarded as they read along. This means the characters need to encounter challenges and mysteries as they move through the story. But this isn't enough. The characters need to figure some of them out and overcome each until they arrive at the big endgame climax. Imagine how Tolkien's epic might have read if it really was just Frodo plodding to Mordor without any little plots in between.

Mini stories on this scale challenge the characters and form the basis of altering their perceptions of themselves and the world. It also does the same to the reader. Presenting this information in story form, makes it entertaining to experience.

But this is not all. Mini stories can be scaled even further. If chapters are mini stories within a novel, a few pages, or even a single paragraph can be a mini story inside a chapter. Sometimes even a single sentence can contain a story when back-loaded to provide for a powerful reveal.

"He collapsed thinking he had failed, thinking he was lost, but as he lifted his head there it was, on the hill, beneath the tree—home."

This sentence shows a mini trip from despair to victory. It is a little story unto itself. So just as matter is made up of molecules and those of atoms and so on, books—good, strong, motivating novels—are made up of stories within stories, within stories. Ideas that loop back upon themselves making clever patterns, resolving questions, supporting ideas. These are the stuff of novels.

Mini stories can also be, and most often are, scenes. A scene is action that takes place in a single location. And just as in a film, it's bordered on either end by a cut to another scene, or in a play, by a dimming of the lights, and or, a change in the backdrop.

One of the most common errors I find is the lack of editing, and what I am talking about here is the cutting of one scene and jumping to the next relevant event. All too often a writer doesn't understand this concept and just writes everything that happens. If a story is of a person discovering they are out of milk and getting more, an inexperienced writer might write of them opening the fridge finding the milk missing, getting their coat and keys, walking to the car, getting in, backing out of the drive entering traffic, going down two lights, entering the store parking lot, parking, walking into the store, getting the milk, paying for it, getting back in the car, driving the same two lights, entering their drive, exiting the car, entering the house, putting the new milk in the fridge. The problem with this is that it's boring and unnecessary. The same could be done by writing how the character discovers they are out of milk and grabbing their coat and keys. Then the scene would cut to a new one at the store where he buys a new gallon. The scene cuts again and he is home at the table drinking a glass of the newly purchased milk. If nothing of significance occurs between important event A and important even B, skip it.

Scene writing allows you to skip the dull parts and keep the reader locked in the juicy stuff. It also allows you the freedom to set a tone and style to the story. Of course knowing when and how often to jump scenes is an art in itself as it defines a good deal of the novel's pacing.

That's the bell. Next week: Pacing. Remember, no running in the halls

Published on August 07, 2011 06:52

August 3, 2011

What's Going On — 8/3/11

It's official. Contacts have been signed. Money has changed hands, and all of the print versions of the old Riyria Revelations have been retired and discontinued.

Should the series grow into something substantial, those of you who have a set of these, perhaps soon-to-be-rare first-edition books, can consider yourself part the elite group of readers who started on the ground floor. You hold a special place in my heart as those who gave me a chance when you had no reason to, who paid decent money to read the words of a guy you never heard of, from an unknown publisher.

You posted reviews on Amazon when I asked, and even when I didn't, and you protested the one-stars with courteous comments. You joined Goodreads groups, nominated and voted for my books to be read. You reviewed my books on your blogs even when you never reviewed independent books, or had never reviewed a book before—and you were kind. You followed my blog, posted comments, and spread my posts around. You twittered tweets, faced Facebook, fanned forums, and saturated cyberdom with my name.

You asked me for interviews like I was somebody worth talking to. You raved about my cover art—art that I struggled with, just hoping not to embarrass myself. You quoted my books on your websites and listed me as a favorite author.

You took a chance reading and discussing my books at your book clubs, even when your clubs didn't read fantasy. You rallied around me in the BSC tournament and carried me to victory against the best of the best.

You bought two sets of paperbacks—one to keep safe, one to lend to friends, and then you bought an ebook version to read. You ordered books and shipped them around the world, from Sidney, to Bangkok, to Bucharest. You told your friends, pestered your family, and let your children and parents borrow them. You even pirated my novels, announcing them worthy of theft and ultimately getting them onto the hands of those who couldn't afford them.

You named your online game avatars after my characters. You even suggested Royce and Hadrian as names to be considered for your grand children. You took the time to write me fan mail that picked me up when I was feeling defeated, and forgave me for missing the release date on the final book. You told me that my novels were more than escapism to you, that they meant something greater and provided something special—something I never expected.

You said I made you laugh, made you cry, made you cheer. And before anyone else, before I ever felt it was true, you bestowed upon me the title of author—you said I was good.

You gave me a gift I can't repay—you gave me my dream.

Enjoy the books. Remember who you are, and what you mean to me.

The Riyria Revelations are dead—long live The Riyria Revelations!

Published on August 03, 2011 09:16

July 31, 2011

Writing Advice 7 — Motivation, the Engines of a Story

When creating a character a very important, and often overlooked aspect, is their motivation as this dictates much of their characterization and how they fit in the story. Most main characters have clear motivations because the story is usually about what they want and how they go about obtaining it. The problem is, sometimes writers stop there.

I once played a computer game back in the early nineties. It was a role playing game and known for having a huge world, with many towns that you could interact with, only they were all the same. Auto generated, the towns all looked alike and the people were all generic copies. It was like some disturbing Twilight Zone episode. It was also boring. Books can be that way too if the only person in the book with motivation is the main character.

In the original movie version (not so much the extended one) of Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings, I couldn't understand why Pippin and Merry joined Frodo and Sam. They appeared to be strangers who bumped into each other on the road and decided to give up their lives, friends, homes, and responsibilities to wander off the map with apparently total strangers. This wasn't Tolkien's fault, he provided all the motivations and back stories in his books, they just never made it to the movie's original release. Yet many novelist make the same mistake of skipping the motivation for supporting characters as non-essential—and then of course there's the antagonist.

Evil for evil's sake—it is an common theme in fantasy, but also pops up in other genres, most notably horror and occasionally thrillers. Fantasy has been around for a long time and in ages past I suspect world perceptions were simpler. How else could nations justify wholesale slaughter of peoples merely because they were barbarians, or savages, or—evil. This black and white attitude lingers but not so much in the modern world of fantasy novels. Readers are showing a greater interest in more complex character motivation, particularly in their bad guys. They are no longer satisfied with a Sauron or Voldemort who are evil and motivated only by power and domination. They want to know…why. (Although oddly enough old Voldemort did surprisingly well for himself.)

When you take the time to consider why the evil menace wants to destroy the world, you realize that destroying the world is a pretty stupid thing in the first place, because it holds no advantage to the destroyer who would presumably die along with everyone else. Enslaving all of mankind? Okay, but why? Is it just an inferiority complex? They want to be the most important? Okay, but why? What made them this way?

The more times you ask yourself "why" the deeper the character becomes, and the more interesting. Also you manage to weed out all the false values, things that don't make sense like wanting to destroy the world. Most people have better motivations than a three-year-old in the midst of a tantrum. The extra work often results in far more interesting plot elements that open whole new ideas that are not only more sensible, but far more interesting, fun, and sometimes even original.

While coming up with motivations aren't all that hard, aligning the motivations so that they interconnect the way they need to in order to make an interesting novel, is. And if you are doing a good job then absolutely every character in a novel, no matter how insignificant, has a motivation. The direction they want to go and the things they want to do extend like dotted lines out into the future in a straight line. You alter them so that they intersect with the dotted lines of other characters and where they meet they often change, skew and shift their angle to head off in a different direction, otherwise known as growth or character arcs. The resulting pattern of dotted lines is the story. It is what drives the characters, and the characters drive the reader. Motivations are the little engines that you wind up and let go. Without them, characters appear false. They become one more prop, like a chair or a table.

Motivations are also logic lines. They should prevent you from doing stupid things. Everyone has read a book or seen a movie where you say, "no one would do that." Usually this is the result of the character's motivation being in conflict with the way the writer wants the story to go. You've likely heard writers say their characters take the story places they didn't expect. This is what they mean. You can either force a story to be what you want, or let the characters follow their motivations and see where that leads. The former always feels contrived and your audience will find it unbelievable. It is almost always best to listen to the characters and let them be the people you made them into. I once had a group of characters who had been traveling through the snow by horse all day and were supposed to leave the road and head into the wilds. That's what the outline called for, only as it happened, there was a town just a few miles ahead and it was late in the day. Almost all my characters wanted to get a nice warm room in the town rather than sleep out in the ice and snow. I didn't want to write a whole chapter concerning their adventures in the town, which I would be forced to do, but no amount of coaxing would change their minds. Why? Because every time I imagined myself in their shoes, there was just no way I would pass up a warm bed. The scene played out that the characters actually had an argument in the middle of the road, and decided to sleep in town. To force the issue would have contrived the plot. In the end, I used the unexpected, added chapter to further develop the characters and the book was richer for it.

Something to keep in mind is that as motivations are the desires of characters based on the information they have at the time, it should invariably lead to characters making the wrong assumptions about others and about the outcome of events and their own plans. All too often I have read stories where the characters always anticipate what will happen perfectly. A good popular example of this is the 2009 Sherlock Holmes movie starring Robert Downey Jr. The film makes use of an interesting flash-forward technique, where Holmes, using his keen skills can anticipate in a fight what will happen and plans out his course of action accordingly. You see the event, and then the scene is replayed and it always occurs precisely as he planned it. Not only did I find this unlikely, and a bit repetitious, I felt it was a waste of potential. For once the technique is established, the sheer drama of this flash-forward failing would be great. We would see what Holmes planned to do, only to have something unexpected occur, giving us two stories rather than a dull rerun.

While this problem can come from sheer laziness, I think all too often it is the result of writers being unable to detach themselves from their characters. When the author is the character, it is a bit like god inhabiting the body of a person. They can't be wrong. Characters should usually be wrong, most people are, or at least only partially right. Otherwise, as soon as a character suggests what might happen, the reader knows it will and you've just provided a spoiler that will steal all the drama from the upcoming scene. However, if the writer can block out all they know and really be just that one character, locked in ignorance, bound by their fears, and driven by their personal desires, their world colored by their past, then it is usually a simple thing to guess at their next move, and their expectations. These will likely not be what is about to happen. The result is a more dynamic and exciting plot that keeps the reader turning pages and surprising them.

There is however a difference between a character making a logical mistake based on what they don't know, and a character being stupid. Sometimes writers cause their characters to make ridiculous decisions, or draw insane conclusions in order to advance the plot the way they want it to go. This is a cheat, and readers know this. To guide characters in the right directions, merely adjust the world around them so that it alters their motivation and then let them go. And if you can't alter the world to accommodate the motivational change, then you'll just have to accept that the story is about to change in an unexpected way.

So you can see how important motivations are. Once set, they can completely alter what it was you expected you were going to write. But having them breathes life into otherwise dead characters and helps prevent stupid mistakes. Let's face it, no one would ever stalk a vampire at night, or even a cloudy day, unless they had an extremely good reason. No one would go back into a wall-bleeding, haunted house unless they had to. Motivations comprise the story that is flavored by characterization and accented by unexpected challenges.

It also needs to be understood that characters don't have just one motivation. Sure Frodo wants to destroy the ring, sure Harry wants to defeat Voldemort, but before that, they both want to eat breakfast. And just as motivation drives the big picture, motivations drive the mini-stories that move the plot forward.

That's the bell. Next week we'll look at Mini-Stories. Remember, no running in the halls

Published on July 31, 2011 06:49

July 27, 2011

Guest Post — Jon Sprunk

Years a ago there was a Saturday morning cartoon called Scooby-Do, Where Are You? You might have heard of it. I was a huge fan when it originally aired, I am guessing sometime in the late 60's early seventies. It lasted longer than most of the new cartoons, but I could tell when the writers were running out of ideas when they started doing crossovers. The "jumping the shark" moment came when Sabrina the Teenage Witch—(a cartoon spin off of the Archies cartoon, an episode that included the famous song Sugar, Sugar)—who was getting her own show appeared on Scooby-do as a promotional gimmick. In the years that followed there were more crossovers, from less reputable cartoons as writers struggled and things spiraled downward.

I'm not sure what that says about my blog as today I am, for the first time ever, hosting a guest blogger. I would like to think it means my reputation, and fame has grown to the point where celebrities are interested in stopping by, rather than a cheap gimmick to keep viewers interested in a flagging series. I suppose that's for you to decide.

Jon Sprunk is the author of Shadow's Son and the more recently released, Shadow's Lure published through Pyr Books. His books are about an assassin with unusual mystical talents and sort of an imaginary friend whose latest job is a setup. There are some obvious similarities between his books and mine, which is no doubt why the universe contrived to bring us together at the recent Balticon convention.The two of us are visiting each other's blogs and meeting for drinks at Dragoncon in Atlanta, at least I hope we are, I hate drinking alone.

So now, without further adieu, I give you Jon Sprunk…

Hello. I'm Jon Sprunk, author of the Shadow saga from Pyr Books, and I'd like to thank Michael for having me over to his place to chat about books and writing.

I get asked a lot why I write fantasy and I was never quite sure how to answer it. Then I heard famed author Robert Sawyer talk at Confluence this year. Robert has a ton of interesting things to say about writing and speculative fiction, but one statement really struck home with me. He said (and I'm paraphrasing, so any inaccuracy is my own fault) that science fiction is the fiction of ideas, of philosophy. In fact, he offered that the field should be renamed "Philosophy Fiction," or Phi-Fi.

I thought about that a lot over the course of the day as I attended panel discussions and talked with other writers. If sci-fi is indeed the genre of ideas and philosophy, then perhaps fantasy is the genre of emotional states. I have always felt in my gut that there is a link between fantasy and heavy metal music, but thinking about them both in light of Robert Sawyer's declaration, both fantasy lit and the harder rock subcategories work from a primal (and oftentimes violent) emotional core. Rage, love, passion. These are the driving forces of many fantasy stories.

For instance, the protagonist of my books (I hesitate to call him the 'hero'), strives to attain the emotionless state required by a professional assassin, but at every turn he struggles against the wellspring of deep emotions bubbling under the surface of his hard exterior. Why did I create him like this? Because I wanted him to have realistic experiences and realistic reactions, and real people feel. We're constantly ruled by our emotions, for better or worse. I think some genres of literature downplay emotion, or treat it as an afterthought, but my favorite stories have always been those that featured emotionally-charged characters.

But (he said with a portentous pause) it's not enough to simply report a character's emotions. "John was sad that his puppy died" or "Sally loved John precisely for that reason" are not significant until the characters actually act on their emotional state. John has to go after the evil neighbor who poisoned his pooch. Sally has to make a desperate attempt to keep John from harm because she can't bear to see him go to prison for murder. Emotions drive action and reaction in our everyday lives, and the same should happen in our fiction.

Take George Martin's epic A Game of Thrones as an example. It has battles and (some) magic and a feisty dwarf, but I would submit that its popularity comes from the fact that all the characters, great and small, are ruled by their emotional states. Just about every action taken in the book is predicated on emotional stimuli; some internal to the character, and others from outside pressures.

But we can go back to older fantasy and see the same elements (if presently a little differently). Robert E. Howard's Conan, and Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. were given to drink and battle excessively to combat their constant ennui. Elric was a passionate brooder; indeed, it was his possession of human emotions that set him apart from his race. Frodo and Sam – don't me started.

Whether about dragons or magic swords or assassins who wield shadow magic, emotions play a pivotal role in the fantasy realm. Our characters ooze angst and snort rage-kindled fires, they love deeply and oftentimes tragically. And that's why I write fantasy.

Jon Sprunk is the author of Shadow's Son and Shadow's Lure from Pyr Books. He lives passionately in central Pennsylvania with his family.

Jon Sprunk is the author of Shadow's Son and Shadow's Lure from Pyr Books. He lives passionately in central Pennsylvania with his family.

I'm not sure what that says about my blog as today I am, for the first time ever, hosting a guest blogger. I would like to think it means my reputation, and fame has grown to the point where celebrities are interested in stopping by, rather than a cheap gimmick to keep viewers interested in a flagging series. I suppose that's for you to decide.

Jon Sprunk is the author of Shadow's Son and the more recently released, Shadow's Lure published through Pyr Books. His books are about an assassin with unusual mystical talents and sort of an imaginary friend whose latest job is a setup. There are some obvious similarities between his books and mine, which is no doubt why the universe contrived to bring us together at the recent Balticon convention.The two of us are visiting each other's blogs and meeting for drinks at Dragoncon in Atlanta, at least I hope we are, I hate drinking alone.

So now, without further adieu, I give you Jon Sprunk…

Hello. I'm Jon Sprunk, author of the Shadow saga from Pyr Books, and I'd like to thank Michael for having me over to his place to chat about books and writing.

I get asked a lot why I write fantasy and I was never quite sure how to answer it. Then I heard famed author Robert Sawyer talk at Confluence this year. Robert has a ton of interesting things to say about writing and speculative fiction, but one statement really struck home with me. He said (and I'm paraphrasing, so any inaccuracy is my own fault) that science fiction is the fiction of ideas, of philosophy. In fact, he offered that the field should be renamed "Philosophy Fiction," or Phi-Fi.

I thought about that a lot over the course of the day as I attended panel discussions and talked with other writers. If sci-fi is indeed the genre of ideas and philosophy, then perhaps fantasy is the genre of emotional states. I have always felt in my gut that there is a link between fantasy and heavy metal music, but thinking about them both in light of Robert Sawyer's declaration, both fantasy lit and the harder rock subcategories work from a primal (and oftentimes violent) emotional core. Rage, love, passion. These are the driving forces of many fantasy stories.

For instance, the protagonist of my books (I hesitate to call him the 'hero'), strives to attain the emotionless state required by a professional assassin, but at every turn he struggles against the wellspring of deep emotions bubbling under the surface of his hard exterior. Why did I create him like this? Because I wanted him to have realistic experiences and realistic reactions, and real people feel. We're constantly ruled by our emotions, for better or worse. I think some genres of literature downplay emotion, or treat it as an afterthought, but my favorite stories have always been those that featured emotionally-charged characters.

But (he said with a portentous pause) it's not enough to simply report a character's emotions. "John was sad that his puppy died" or "Sally loved John precisely for that reason" are not significant until the characters actually act on their emotional state. John has to go after the evil neighbor who poisoned his pooch. Sally has to make a desperate attempt to keep John from harm because she can't bear to see him go to prison for murder. Emotions drive action and reaction in our everyday lives, and the same should happen in our fiction.

Take George Martin's epic A Game of Thrones as an example. It has battles and (some) magic and a feisty dwarf, but I would submit that its popularity comes from the fact that all the characters, great and small, are ruled by their emotional states. Just about every action taken in the book is predicated on emotional stimuli; some internal to the character, and others from outside pressures.

But we can go back to older fantasy and see the same elements (if presently a little differently). Robert E. Howard's Conan, and Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. were given to drink and battle excessively to combat their constant ennui. Elric was a passionate brooder; indeed, it was his possession of human emotions that set him apart from his race. Frodo and Sam – don't me started.

Whether about dragons or magic swords or assassins who wield shadow magic, emotions play a pivotal role in the fantasy realm. Our characters ooze angst and snort rage-kindled fires, they love deeply and oftentimes tragically. And that's why I write fantasy.

Jon Sprunk is the author of Shadow's Son and Shadow's Lure from Pyr Books. He lives passionately in central Pennsylvania with his family.

Jon Sprunk is the author of Shadow's Son and Shadow's Lure from Pyr Books. He lives passionately in central Pennsylvania with his family.

Published on July 27, 2011 08:57