Michael J. Sullivan's Blog, page 87

October 21, 2011

Walking On The Moon

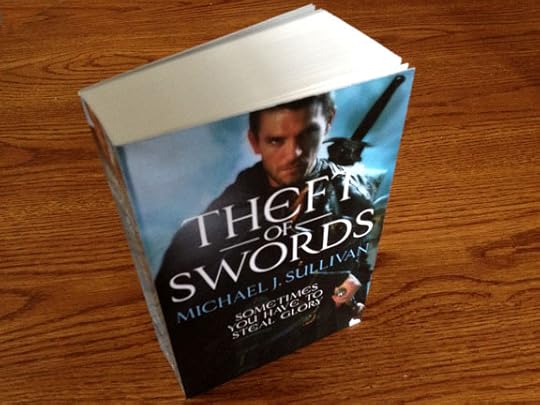

I recently received copies of the UK edition of Theft of Swords, and upon seeing it a friend remarked, "So this is it. This is what it all comes down to. Wow, you must really be proud."

This isn't the first time I've seen my book in print of course, but he's right, seeing your book for the first time is incredible. When I got the very first edition of The Crown Conspiracy in the mail with a cover that none of you have ever seen, depicting a crown and dagger in a puddle of blood, I was ecstatic. I played with it like a toy. I sat down and read the whole thing. It is an amazing sensation to read your own book. I think it has to do with the familiarity with the physical act of reading a book. Sitting on the couch, turning the pages, seeing the printed words just as I had done with my favorites over the years, getting lost in the story, but knowing I wrote it, was surreal in an extremely pleasurable way.

This sense of associating good and bad experiences with things and places that makes the experience of reading your own book for the first time so wonderful, I think lies at the heart of the whole ebook verses print book debate. I'm sure many theatergoers had similar issues when movies were shown on televisions, or when movies learned to talk. When I was a kid, I remember everyone discussed how television, and its three stations, were ruining the American family. Now no one talks about that anymore. It is the computer, and gaming consoles that are the new enemy. And I find myself remembering the evenings when my family gathered around the tv to watch a movie, The Wonderful World of Color (back when color just debuted and Disney was capitalizing on it,) or a Jacque Cousteau special. And how the next day at school, everyone else had seen the same things. The very destroyer of the American family had actually, in retrospect, been the nexus, the replacement for the radio in the living room, or the piano in the parlor. I find that computers cause everyone to live more insulated lives, communicating in text messages instead of walking in the next room and speaking. But in thirty years, people will likely be remembering the good old days when there were only three gaming consoles and everyone played the same games together over the same network, and how that was a cultural bonding experience they regret having lost.

For people my age, printed books were huge. I started reading relatively late finishing my first novel at thirteen. I can still remember when books on shelves were mysterious things. Doorways into the unknown that I was intimidated by because I wasn't a very good reader. Then when I finally discovered the joys of reading, it was by sitting in a chair, or curled up on a bed, or tucked in the backseat of a car with a small paperback book in my hands. Later, when I had the money I bought hardcovers—the luxury vehicle—and I felt ever so more worldly and sophisticated to turn those pages, even if I couldn't tuck them in a back pocket.

I've heard people speak lovingly of the smell and feel of a book. This puzzles some as the smell of a book isn't necessarily a nice smell. It is usually ink, if it is a new book, or mildew, if it's an old one. But I don't think that's the point. It isn't the smell of the book so much as the smell of memory. I used to play tennis, and I had many wonderful times doing so, and to this day the smell of a recently cracked tube of tennis balls is like pine on Christmas morning. I suspect this very pungent scent is actually just glue and rubber, something that without context anyone would abhor as an industrial stench, but because it carried with it wonderful memories, I like it. In many books and movies similar comments are always made about the smell of a baseball glove, or the green of the grass.

I imagine an actor doesn't feel they have achieved success until they sit in a theater and watch themselves on the big screen for the first time, or perform on a genuine theater stage—one where they once sat in the audience. Mothers may not truly feel like mothers until they hear themselves accidentally say something their own mother did that they never thought they would repeat. A man might not truly feel like a man until they look in a mirror and notice how much their gray hair makes them look like their father. Handling and reading a printed book is like that for someone like me who grew up with them.

That won't always be the case. Searching though files and seeing the cover of your book and downloading it to an eReader will be the same thing for the next generation. And when books are read on retina lenses, or uploaded directly into the brain via neural network jacks, they will laud the ease of use, the lack of needing to carry that old clunky eReader around with them, but they will lament the loss of tactile memories. How can it be a book if they can't press the button to turn the pages? They will continue to carry their eReaders with them even after they can no longer download books because that little electronic slate is their friend. Beat and battered it is their most loyal pal who kept them company when they were bored, or who devilishly kept them up when they really should have been sleeping. It's their buddy who taught them new things, showed them new worlds, and helped define what kind of person they would ultimately become. How could they throw that away?

Holding the new, fat volume of Theft of Swords and reading it, is still a rush, and I am glad I was published in time to see it—in the event print books become an exception rather than a rule. It takes me back to those days when I was thirteen and held an equally thick (or so it seemed to my smaller hands,) copy of Fellowship of the Ring, and reminds me of when I used a typewriter, poster board and stapler to create this very thing I now hold. And seeing my map, my table of contents, my chapter heads and feeling the magic that any book can cast, is like being that kid who played astronaut only to later walk on the moon.

So yeah…it doesn't suck.

Published on October 21, 2011 06:16

October 16, 2011

Writing Advice 17 — A Reason To Read

[image error]

Recently I touched on the importance of making a good first sentence, and a compelling opening scene. The focus of that was to provide the gravity to pull in a new reader or persuade an editor to put your manuscript in the "to be read later" pile. That's all very important, but what happens when that editor or that reader finally get around to reading the next fifty pages?

Mysteries Aren't Just For Thrillers

I consider writing a book similar to coaxing a wild animal into a cage with bits of food. You put the food down on the ground in a line to the cage. Or if you prefer, and have seen the movie ET, you're trying to lure an alien with Reeses Pieces. The problem is that you have a limited amount of candy, so the question becomes how far can you space the placement of food and not lose ET prior to getting him to the shed?

A great opening to a story is like offering a nice bit of candy. People taste it, like it, and hope for more. If you give them another, they will stand where they are and eat it, but you don't want that, you want them to move. Besides, after too much candy, they will get full and no longer want to eat. So instead of giving them a second, being that they are humans and not a squirrel or rabbit, you can promise them one—if only they will go over there.

The fireworks at the start of a story catches a reader's attention. Mentally they might think, "Okay, that wasn't bad, I'll give this writer a few more pages now and see if they can maintain my interest. You now have sort of a loan of time with which to build an interest. The investor is still very skeptical however, so you'd better show them something soon.

As I said another bit of candy won't work so well, you need something more substantive. The best, I feel, is an interesting question or compelling proposition. In a mystery story, it would be the puzzle that the client tells to the sleuth—the mystery.

"My husband died while trying a Houdini escape from a submerged, sealed cement block wrapped in chains."

"That's unfortunate, but why are you seeking my help?"

"You don't understand. He was shot to death. Five bullets, and no gun was found."

After reading that, you want to know the answer. You want to find out how this is possible. You'll go looking for that next Reeses Pieces.

Only that can't be the whole thing. If the answer to that one question is the sum of your story, it is like spacing the candy too far apart. If I have to wade through three hundred pages for just that last treat, I'll get bored and stop. So you need to add more treats.

If you reveal that the man was shot before entering the box, but then discover that the man in the cement box wasn't actually the woman's husband, you have allowed the reader to have their Reeses Pieces, but then promised them another. This end-to-end reward and promise method works well to move a reader much the way Spiderman swings through a city, shooting one web while swinging from another. Still I find it too simplistic. An extra layer or two can really help make the story richer and the need to turn the pages that much more intense. So running several mysteries at once, staggering their paths of reward and promise differently than the first ensures that the reader stays riveted. If done well, there will be short-term puzzles, longer questions, and story (or series) length mysteries. Each one working as a sail to catch the wind of a reader's interest and move them forward.

Conflict

In addition to the mystery, you'll need conflict. Most stories are all about conflict. The protagonist has a goal, and the antagonist is in the way of that causing conflict. This is possibly the most basic definition of a plot. Without it, you don't have much of a story. I've actually read pieces that lacked conflict, short fiction mainly where events happen, and a character reacts, but there is no dispute, no struggle, and the writing simply ends at some point.

My rule for determining if you have a plot or not is to see if you can describe the story without describing the events that make it up. If you can say, "It's about Bob, who is desperate for money so he robs a bank." That's a story. If on the other hand your description is, "Bob has a hard life and I reveal that over the course of the story," and feel that doesn't really describe the story without explaining the events…that's not a story, that's a detailed character workup. Or if you say, "It's about a world where they have suddenly lost the use of electricity." While this has an implied conflict of Man Against Nature, it isn't so much a story as it is a setting for a story.

This said, there are many books on the market that according to this breakdown would not classify as stories, which are very successful, so clearly this isn't always a problem. I would venture to guess that stories with plots are more commercially successful, where as those without tend to be more critically acclaimed. I've actually heard rumors that lit professors denounce plots as inconsequential and annoying as they merely get in the way of the important aspects of a book which are theme, symbols, meaning, etc.

Conflict between characters will also generate a desire to read. Hatred for an antagonist can turn pages just as effectively as concern for a protagonist. In recent years there has been a resurgence of authors killing their protagonists and letting the antagonists win. This can result in readers throwing books, or in the case of The Princess Bride: "You mean he wins? Jesus, Grandpa, what did you read me this thing for?" On the other hand, a hero that wins the day, is a bit like a spoiler.

No matter how you chose to do it, conflict should be a large aspect of your story if you want to keep the reader reading.

Tension and Suspense

If Mystery is the cerebral part of this equation and Conflict is the physical aspect, then Tension is between the two. Tension is created when the two conflicted elements enter into the same proximity. Nothing has to happen, it is often best when nothing does, but the tension it causes will rivet the reader. This is derived from the conflict and can help keep the reader's attention even when nothing is really happening, or can't happen.

Suspense is lengthening an exciting scene, building emotion. The enemy draws near, the clock ticks, just seconds are left, but in the narrative those moments will take three pages to complete. And a reader will read every word, and ignore phone calls, dinner and sleep to finish them.

Using each of these elements, Mystery, Conflict, Tension and Suspense and layering them like shingles so that they overlap leaving no gaps where something is not nagging at the reader to turn the next page, is how, as a writer, you keep your reader with you, how you get ET into the shed. No matter what your theme, genre, or how profound your message, if you can't entertain well enough to cause your audience to finish your work, nothing else matters—you need to give your readers a reason to read.

Next week: Voice

Published on October 16, 2011 09:59

October 14, 2011

A Giant, a Fish, and a Cheerleader, Went Into a Blog Post One Day...

I had a good laugh today.

In case you don't know, Scott over at Iceberg Ink wrote a very nice post about me. This isn't the first time. He's written reviews of all my books, and one on my move to Orbit. This one was a more comprehensive overview of my work and his association with it. And Scott doesn't just compliment me, in his own words he "gushes" and he praises my wife as well.

If you read the SandyBeach post I wrote a few weeks back (and jeez did a lot of people like that post! Who knew.) You'll understand what I mean when I say Scott qualifies as a Superfan. I know all of my superfans by name as a prerequisite for being one is having contacted me. Scott recounts his first correspondence with me in terms of "a teeny, tiny fish emailing a giant."

That was the laugh.

First it's funny because fish don't email. Second…why a fish? But mostly, the sheer suggestion that Scott is tiny and I am a giant, was hilarious. It's funny because I suspect he actually thinks this. The reality is that Scott is a very respected member of the blogging community who has done an enormous amount to help my career. I am one of thousands trying to catch the attention of people like Scott. I am a pimply-faced, teenage geek trying to get a date with a college cheerleader, and not only did he notice me, he went out on a date. Then he admitted to his friends he went out with me. (Sorry for comparing you to a cheerleader Scott when you were so nice as to compare me to a giant. And I'm assuming it was one of those handsome Nordic giants with the broad shoulders and billowing beards, not a Jack and the Beanstalk, potbellied pin-headed, Disney kind.)

I know that fans imagine authors, or actors, or musicians to be otherworldly—somehow more important than they are. That's like an eagle thinking it's more important than the air currents it rides on. (Just trying to keep with the metaphor theme of this post.) I suppose some of them even get to believing this is true—not eagles so much as artists. It's not always their fault (still talking about artists and not eagles.) When a person tells you your greater than everyone else, and you hear that enough times from enough people, it can warp your reality. Lucky for me, I spent enough time being ignored and read enough bad reviews that I have a pretty firm insecurity foundation and it's hard to be swept up.

On my side of the fence, looking out my window at all of you, I'm just one more person who wrote a few books because I was bored. It doesn't take a lot of upfront investment to be an author, just time—which is why I still love watching this video. I know a lot of people who have written a book and not gotten anywhere. I happen to like my books a lot, but then they are tailor-made to suit my taste. Still, I don't expect other people will love them. Everyone has things they like in books and things they hate. (Pet peeves are one of my pet peeves—what the hell is a peeve anyway and do they make good pets?) I know this because I am a highly critical reader. I think that comes with being a writer. The better you get at it, the less you can enjoy the works of others. It's like a ballet dancer who no longer sees the beauty of Swan Lake, but only notices the technical mistakes. (Yeah, another metaphor, but that was a good one.)

So I did this one thing, like another person might make a great dinner, or build a really cool snowman, or play a great game of chess, only somehow writing these books elevated me in the eyes of others—well at least those I don't personally know. I had a friend who recently mentioned famous people, and then paused, looked at me and said, "well, your kinda famous." It took me a second to follow what she was saying. Then we both laughed.

My point is that even if I really were a huge name in literature, I'd still only be this guy who makes up stories and writes them down. But I'm not even that. In the pond of indie authors, you might have heard of me, but in the greater ocean of publishing that I've fallen into, I'm that teeny, tiny fish just trying to make a splash. And Scott, you're the really cool sea turtle from Finding Nemo calling me the Jelly-man, or maybe the pelican flying around telling my story.

However you metaphor it, thanks Scott.

Published on October 14, 2011 07:55

October 12, 2011

Why I Don't Know Anything About Writing

If you've been reading my Sunday blog posts on writing tips, and if you happen to have a degree in creative writing, you might have come to the conclusion that I don't know what I'm talking about. That's because I don't—at least not in the collective-mind, homogenized, social understanding sense. The communication age has managed to offer mankind a huge leap forward by granting a never before known ability to share ideas. Given that the total discovered knowledge of our race can no longer be contained in a single brain the way it used to—stab to kill, fire to cook, hide from storms, don't eat the red berries—the ability to access previously worked out problems is a massive benefit. It is also one which I am apparently too stupid to take advantage of.

I've always been this way.

When I was nine my father died from pancreatic cancer, and my mother moved the family from Detroit to an almost non-existent, distant suburb of Novi. Legend has it the name comes from "Train Station No. 6." In the late sixties, that's about all that was there too. Cornfields, apple orchards, and dirt roads made up the rest. After living on the concrete and asphalt of Detroit, I loved the country. I was a big fan of Fess Parker's Daniel Boone series and the idea of having a forest in my own backyard was exciting. This excitement was tempered by the fact I didn't have a backyard. We moved into a park-home condo, that had all the charm of an army barracks and a yard that consisted of a tiny patio. I also didn't have any friends, and I wasn't the kind to make them. Introverted and shy, the move left me isolated. I spent my days exploring the woods alone sometimes wandering as far as ten miles away, and when it rained, or snowed, I stayed inside and wrote stories, or drew pictures (no Internet, no computer games, no cartoon channels.)

I taught myself by studying what others did. I copied paintings or drawings of artists I liked, and I wrote stories emulating the authors I enjoyed. In this way, after literally years of practice, I got pretty good. Good enough to win a scholarship in art. I never showed anyone my writing except the very few close friends I finally managed to obtain. I knew my spelling and grammar was so awful that anything down that road would just be humiliating. Those few friends made a habit of reminding me of this.

I went to college on that scholarship—an art school. I discovered something about myself there. While I love the idea of school, I don't do well in that environment. I have this crazy notion that I know more than the teachers, that they are trying to teach me things I don't need to know and don't know that which I am trying to learn. When I began teaching other students what the instructor failed to, the teachers didn't like me either. I eventually dropped out and got a job as a grunt illustrator at a company that did presentations slide shows for car companies. When the Detroit economy slumped, so did my job. My wife had graduated from engineering college by then and she made enough that my staying home to raise the kids was a no-brainer.

During that time, personal computers were hitting the market along with the fear that artists would be replaced just like the factory workers. I got my first machine in the mid eighties. I had this crazy idea of seriously writing a novel and trying to actually get it published. I was about twenty-three years old and didn't have a clue what that meant, or as it turned out, how to write. All I knew was that when you were writing hundred-thousand-word novels, typewriters sucked. It was a pipe-dream and I wasn't going to throw any more money at it, so I never considered a class or even a book on the subject. To be honest, it never crossed my mind that such things existed. I proceeded once again to teach myself. That's just how I figured it was done. You can't teach creativity, it was something you had to drag out of yourself. I spent a decade dragging.

Computer's improved and Photoshop was born. Few people knew what it was. There were no classes in it, no books on the subject. That was okay, because I only spot read the manual anyway. I learned by playing with it—that and a few other programs like Quark and Illustrator. I made a monthly magazine for my friends—staple-bound with full color glossy cover. I did this for years. I never thought of it as a skill. Sure I could do some pretty neat stuff, but I didn't have a degree. So I was surprised when Robin, who hated the marketing materials of the company she worked for introduced me to her boss.

"Ask him," she told me. "Go on. Ask him.""How do you make your marketing materials?" I asked. "Powerpoint," He said.I blinked. "No seriously."He looked puzzled.

I re-designed their brochure at home that night and brought it in, and I had a new job the next day. Clearly no one there could help me. No one there could teach me my new job. They didn't even try. I was a bit bewildered my first few days when I sat at my empty desk expecting someone to stop by and tell me what they wanted me to do. Robin explained, they couldn't do that because they don't know. That's why they hired me. Oh.

I never looked back. I ordered a computer and the programs I wanted. I decided what the company needed and set about making them. Never having professionally printed anything from a computer file, I went to print shops to ask what they wanted from me. Only one printer in the city (this was in Raleigh) knew how to print from files to plates. Everyone else was still using paste-up cameras. Together we worked out the bugs, and by trial and error, I taught myself my job.

I wasn't an idiot. I assumed I had missed stuff along the way. By this time I had used Photoshop for a whole decade, but still had never read the manual, and it had gotten a lot thicker. I took a free seminar a guy gave on Photoshop basics. I felt sort of stupid being there, but I learned a handful of things I never knew, like that there were shortcut keys to switch tools. Really? That would come in so handy.

Stuff like that—the unknown knowledge that is unobtainable by observing the finished product, or by trial and error—is what I missed. I've often felt that the discovery of penicillin might have been like someone accidentally hitting a shortcut key and going, "WTF?"

I suppose if I had still been writing at the time I might have applied that same understanding to writing, but I had given it up by then. I had a new career. I started my own advertising agency offering better quality materials and ads to new technology start-ups, for half the cost of the big agencies, because I did everything on computer while they were still doing photography and key-lining. When I finally got tired of making my one millionth brochure, I went back to writing, but I still wasn't serious about it. I wasn't going to get published, but then Robin found me an agent.

My agent was the one who showed me the two huge shortcut keys I had been missing. Point of View and Show Don't Tell. I had already been correctly doing those things, but not consistently. I had merely worked out that the story read better when I didn't narrate the action, and that sticking with one PoV per scene made it easier to present an idea. When she wrote to me explaining these two points I was like that science fiction scientist who meets an advanced alien in human disguise who writes the solution to a mathematical problem on a blackboard and the scientist's jaw drops. WTF?

Since then I've joined writer's groups and I have looked at a few books on the subject of writing, and these have helped polish my understanding, but nothing so dramatic as those shortcut keys my agent gave me. As a result, I suspect that my writing tips are not consistent with the norm. None of it comes from books, or seminars, or classes. I don't have a MFA or a BFA…I don't have any letters at all after my name. Everything I write in those Sunday posts is just stuff I taught myself over a couple decades of trial and error. I'm the Photoshop guy who learned how to create drop-shadows and bevels long before the one-button filter was added to the program. Sometimes I still do it the old way.

So if you find my tips to be a little odd, or not exactly what you were taught in creative writing, it's because I really don't know what I'm talking about. Everything I've written, I've made up. It might be all wrong, but it's all I know. I just thought that somewhere buried in all that you might find your own shortcut key.

Now that I think of it, maybe I do have three letters I can put after my name—WTF.

Published on October 12, 2011 08:20

October 9, 2011

Writing Advice 16 — Making it Snow

So far I've spent a lot of time explaining a lot about the mechanics of writing, techniques and mistakes to avoid, but how do you actually handle the conception of a story? How do you build one? How do you create a complex, inter-weaving, multi-layered, emotionally-moving, laugh-out-loud-funny, scare-the-crap-out-of-you, story?

As it turns out it is remarkably similar to the formation of a snowflake. Both are complex structures that seemingly appear out of nothing, and while they all look the same—no two are ever really alike.

So how is a snowflake born?

A snowflake begins to form when an extremely cold water droplet freezes onto a pollen or dust particle in the sky. This creates an ice crystal. As the ice crystal falls to the ground, water vapor freezes onto the primary crystal, building new crystals – the six arms of the snowflake. —NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.)

Snowflakes then are nothing more than structures built onto bits of dust. Now imagine for a moment that in this analogy, dust is an idea. I'm not talking about grand ideas, nothing so elaborate as amber encasing a mosquito that feasted on dinosaur blood making it possible to access dino DNA and clone them in modern times. Those are the "what-ifs" of novels. What if an obsessive compulsive detective begins looking into the murder of his own wife to discover real vampires living in San Francisco? That's the kind of thing you get from watching an old episode of Monk followed by an old episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. No. I'm talking about what happens next, when you face that blank glowing white box of your word processer. Where does all the other stuff come from? A fully formed novel doesn't just plop out of an author's head. There is a process of growing it like an ice crystal, but ice crystals can't form on nothing, they need a bit of dust, an idea.

One of the best ways to provide this is to start in a logical place and ask yourself a simple question like, who is your main character? Even that is too big a question, so you break it down to what does he or she do for a living? Maybe the story is actually a what-if about a virus that kills most of the world's population in just a few months, so really what your character does for a living might not seem terribly important. They can do anything because they won't be doing it for long. So you pick something at random. You think about people you know, people you meet over the course of an average day and what they do. You just had lunch at a Ruby Tuesday and so you decide she will be a waitress at a chain restaurant.

Boom! You just made a bit of dust.

This is now a platform you can build on. The character is a woman who is on her feet all day, meeting people. So one of the most important things in the world to her are comfortable shoes. You just made a character attribute that grew out of the dust speck. Building on that you realize she never wears heels, she rarely dresses up. Great, you now have a mental picture of this person that you did not have before.

Staying with the original bit of dust, you can continue to build off that. Since you know where she works, since it is the one setting you have, the first scene of the story is now going to take place in the restaurant where she will meet her love interest. He will flirt with her while all around the other patrons are sneezing and coughing more than normal. Must be flu season? Over the course of the story, as the virus spreads, less and less people will come to the restaurant. Until it is only her and the love interest who will have a touching scene on the night before the restaurant closes. Is one or the other sniffling?

Voilà! The first fifth of the novel has just been fleshed out. That one particle of information, that was so irrelevant when you conceived it has led to a huge plot advance—just think what might have happened if instead of going to Ruby Tuesday, you had just gone to a Seven-11 for a gallon of milk.

One particle of dust provides the foundation on which you can slap extensions. You start with one idea about a character. That idea leads to the next. If the character works in a library, they can be very bookish and read all the time, or you can play against type and make him hate books, or better yet—he's illiterate. At this point you need to explain why. That leads to other answers and other questions. Soon you have a pretty defined character. Now if you want to try weaving a story, flesh out several characters and a few settings, and see where unexpected connections occur.

1. Protagonist: An orphan boy, actually the illegitimate grandson of a wealthy man who's daughter ran away from home. 2. Setting: The streets of a bustling, dirty city filled with crime. 3. Antagonist: A hoodlum who uses orphans to steal form the rich.

Put these three together and you can weave them so that the hoodlum ensnares the poor orphan to rob from a rich man's house…who turns out to be the boy's grandfather, causing the story to have a happy ending. (Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens is almost like this.)

Sometimes people have what some might call writer's block. They just can't think of anything. (Note that different people have different definitions of this affliction. Some consider it when they can't think of any ideas, for others, they have ideas, they just can't bring themselves to write, being too easily distracted.) The traditional solution to this problem is to just start writing. Write anything. It doesn't matter what.

Hello. I don't know what to write. I must be the worst writer in the world because I can't write. This is what most people must call writer's block…

How does this help? Random writing can accidently result in random bits of dust forming, that your writing mind can start building ice formations around.

…Writer's block. An odd phrase. Is it a person, place, or thing? Is it an actual block like a brick that an author can't move? Or better yet something he can throw when he is as frustrated as I am? Or is it an obstruction like something they have to remove from a bowel? How cool would it be if it was a city block? A street somewhere inhabited by authors. Not just random writers either, but famous authors…living and dead. Ghosts of Hemmingway, Joyce, Twain, and Dickens haunt the likes of Stephen King, James Patterson and Danielle Steel inspiring them to greatness. What if a new aspiring writer managed to obtain a home on that street. A home no one else wanted. What if all the writers who lived there were successful because of the ghosts who haunted their houses, but no one wanted to live in the house that the aspiring author was about to move into, because the ghost that haunts that house has caused the last five aspiring authors that lived there to commit suicide. Hey…I don't think I have writer's block anymore.

Writing throws up dust. Dust forms the nucleus of an ice crystal. Ice crystals gather more ice crystals, growing in all directions until at last, when they gain enough weight they fall as snowflakes. And if you create enough flakes, very soon, it will begin to snow.

And there's nothing quite so lovely as a blanket of new fallen snow.

That's the bell. Next week—A Reason to Read

Published on October 09, 2011 12:22

October 2, 2011

Writing Advice 15 — How To Begin

What's the most important invention of all time? One person claimed it was the computer. The next said no, computers wouldn't work if not for electricity, so electricity was more important. The next claimed electricity could not have been invented without writing which allowed the sharing of ideas, so writing was more important. Finally, someone said, you could not have had writing without language. So language was the most important invention of all time, because it came first and without it, none of the other inventions of mankind would have been possible.

This idea of one thing enabling the next and therefore by this virtue being more important, is what makes the beginning of any story the most important part. To put it in a more practical sense, editors, slush-pile workers, and general readers have a tendency to only look at the first page, or even the first few sentences, of any book before deciding to either drop it or keep it. So unless that first page is good enough to grab your reader, you'll never have the chance to invent electricity, or a computer.

There are three things to keep in mind when starting a story.

1. Start your story where the story starts.2. Ground your reader immediately3. Make the first sentence kill.

Start Your Story Where The Story Starts

I was recently at the Baltimore Book Festival and heard author Toby Devens talk about how when she wrote My Favorite Midlife Crisis (yet), her editor told her that her book started on chapter three, and asked why she "cleared her throat" for three chapters before getting to it. Toby loved her first three chapters, but trusting her editor decided to cut the chapters and sprinkle that info throughout the rest of the book, after doing so she realize how much better the book became.

This is not unusual. Most authors have discovered this phenomenon, this tendency to have to settle into a story before starting it, and then having to go back and trim off the front end excess. I'm not sure I've ever written a book that began where I first started writing. Avempartha had the first chapter and a half cut. Nyphron Rising used to start on what is now page 101. And Theft of Swords had a whole new section added to the first chapter of what was The Crown Conspiracy.

Most of this is due to the writer's misplaced desire to establish a foundation, to present some basic information they feel the reader will need to fully appreciate what comes next. This is also called, Setting the Stage. This is the most logical concept in the world and is also one of the worst things you can do, because by the time you've adequately set the stage to begin your story, your reader has already grown bored and closed the book. The solution to this problem is to start with the event—the "action"—and (just as Toby did) sprinkle what used to be the stage setting, in the cracks. Hook the reader, get them interested, then and only then, present them with the information, which by that time they are dying to know.

So many books begin with a lifeless description that says nothing. This is particularly prominent in invented-world fantasy where the author likes to jump right in and start educating you about their world.

In the year of the Exnox, before the reign of the One-Handed King, when Asifar was still a province of Tripidia before the first of the Haglin Wars that decided the fate of all the inhabitants of Estifar, a boy was born to the tribe of Grangers and his name was Firth. It was in the wet season the Grangers called Kur that the boy was born into the house of Janicy, who were known for their hunting skills. All Grangers were known for hunting as well as archery as their ancestors came down from the Ithinal Mountains to…

Get my point or need I go on?

In this story, which I just invented as an example, but which is typical of the beginning of about eighty percent of invented-world fantasies, the story would go on for about thirty pages of this sort of thing until in the third chapter or so, after little Firth has grown up a bit you might read:

The axe came down at his head and Firth dove to the side to avoid being cleaved in half. Trevor was supposed to train him, not kill him, but before Firth had gained his feet, Trevor was swinging again.

This is where the story actually starts. All that other stuff, all those thirty pages covering the history of Firth's tribe and the world as well as Firth's youth, can all be sprinkled in along the way of the story, being brought up when the story requires it. A funny thing can happen if you do this. You discover there never is an appropriate place to add all that back story and world building —what's more you discover you don't need it. All that junk just isn't necessary for the story. It's great for you, the author, to know as it helps underpin the reality of your world, but other than that it is just extra stuff that weighs a story down. It is the scaffolding and sheets that need to be removed once the building is up. Some readers have developed a taste for excessive world building that extends far beyond the scope of a story, but I feel this writing style is what keeps fantasy from reaching more mainstream readers, who would prefer not to have an invented history lesson to go with their story.

And if you're writing a thriller, well…you'd better thrill right out of the gate. The floor needs to drop out from under your character's feet and he/she needs to be in near constant free-fall at least through the first few pages. I've never written a romance, but I'm actually thinking a sex scene would be a great way to start one. If you're doing a mystery, start with the unanswered question.

There is a flip side to this that you need to be aware of. Starting with "action" (action is in quotes because I don't actually mean physical movement, but an event-of-note,) can be detrimental to the story if there is no context to give it value. Which leads me to the next thing to keep in mind.

Ground Your Reader Immediately

It can be extremely irritating to a reader if a book begins in a nebulous space where nothing is defined. This is one of the reasons I hate the relatively recent trend to create prologues, as prologues are almost always designed to be nebulous things. Moments out of context where the subjects, actions or settings are often never identified.

Heil struggled to grasp the plastic toggle that flittered about like an insane snake. She shifted her shoulders and hips, and found herself spinning, which only disoriented her more. Time was running out and still she had yet to even touch the toggle with her freezing fingers. What if it did nothing? Heil's heart hammered in her chest and thundered in her ears. If only she could grab it. But what would really happen then?

This story starts with heart pounding action, but for all its urgency, it isn't compelling because we have no idea about anything. Who is this person? Where are they? When are they? What's happening? What's at stake? None of it makes sense, and unless answers are very soon forthcoming, frustration will cause the reader to close the book.

It is therefore important to ground your reader, plant their feet securely on a stable footing. I always imagine that when I open a book I am being teleported though a random portal and will appear somewhere inhabiting the body of someone else. Just like in the old tv show Quantum Leap, the first thing I want to know is who I am, when and where I am, and what am I doing and why. Until I know this I feel disoriented and I am not focusing on the story so much as trying to answer these questions. Sometimes this "reader in the dark" technique is useful—most often I see this used successfully in short fiction where discovering what's going on is the story. Other than that, starting a book and keeping your reader hooded like some poor hostage will likely cause them to have similar feelings about the experience. The best way to provide the needed information is by using the techniques in the previous blog post—multitasking—to present the "action" while at the same time slip in these essentials that provide the event with context and, as a result, value.

Consider how much more the previous scene would mean if it began:

Heil had ten more seconds to discover how to pull the ripcord before she hit the ground.

And finally…

Make the First Sentence Kill

If the first page is the most important because it comes first, the first sentence is the most important of the most important. The holy of holies. This, all by itself, can be the difference between someone publishing you, or reading you. At that same Baltimore Book Festival author Michel Swanwick explained how experienced slush pile editors only read the first and last sentences of a manuscript before deciding what pile to put them in, "read later" or "reject." The first sentence is also, as in sports talk, one of those stats that are remembered and quoted.

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.— George Orwell, 1984

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. — Jane Austin, Pride and Prejudice

Who is John Gault? — Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

These are just a few of the classic first sentences of novels.

Oddly enough, one of the most famous first lines ever, (and a lot of people's favorite) I personally feel, is one of the worst. That would be Charles Dicken's Tale of Two Cities:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…

That's usually all anyone knows, and most think that's the whole sentence. It's not. This is the full sentence:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we were all going direct the other way - in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

That's one sentence, a total of one hundred and nineteen words. Com'on grammar Nazis are you going to tell me this sentence is not rife with errors? The man's not even using semicolons to separate complete sentences. The real problem I have with this sentence is that, aside from being an insane run-on, it ultimately says nothing of value beyond what could have been encompassed in "It was a day like any other day," which is about as tedious a beginning to a novel as I can think of. So the man wrote over a hundred words to say something that wasn't necessary.

Before I get hate mail from Dicken's fans, I should mention I love Dickens. I also recognize that he wrote in a different age—it was a time of elaborate exposition, it was a time of wordiness, and times have changed—reader's tastes have changed with them.I'm pretty sure if someone submitted this as the first line of a modern manuscript, it would be rejected fairly fast.So the first sentence of your book should be a thing of beauty that can be taken out of context and still rock people's worlds. Although I still suffer from chronic depression, I don't hear the voices anymore.The door handle turned, the light went out, and all I heard was screaming.These are first sentences waiting for a story. A good first sentence should make you stop and think…whoa—I want to know more. It is the single showcase for your literary skill, the dressed front window of your Fifth Avenue store two weeks before Christmas. It needs to draw customers inside with its exquisite beauty, clever wording, and shocking impact. The problem with creating the world's best opening is that you can't just stop there. A common mistake is to craft a perfect first sentence, then pull a bait-and-switch, where the sentence really has nothing to do with what follows. This is the sort of bad reporting you might find on a really sleazy news show. The President drown today...…in a sea of red tape. Whatever clever beginning you create to capture the reader, you need to make it pertinent to the rest of the paragraph and to the story as a whole. Readers don't like to be lied to. So start your story where it begins, not after your reader has closed the book; ground the reader to provide context value, and punch the reader hard in the face with a stunning first sentence that will keep them reeling until you so thoroughly wrapped them up in your tale they will never escape. That's the bell. Next week: Making it Snow

Published on October 02, 2011 12:04

September 30, 2011

The Viscount and the Witch, short story

Hello all,

This is Robin (Michael's wife for those that don't know). I'm commandeering his blog to announce: The Viscount and the Witch. This is a little short story Michael wrote at my urging because...well as some may know I'm in love with Royce and Hadrian (sorry hun, but you know it's true) and I just can't get enough of them.

This is a strange time...the Ridan books are out-of-print and the Orbit books (although available for pre-order) won't be available for reading until Thanksgiving so, after three years, we have no books for sale ;-(

As we've both said, there will be no seventh book to the Riyria Revelations. That particular story wraps up completely in Percepliquis and to "tack on" another just isn't going to work (and no amount of needling will get Michael to do -- trust me on this).

But...Royce and Hadrian spent many years together before the event that happened starting in The Crown Conspiracy so I begged, pleaded, and offered "favors" to get a tale of the "early years" and hence The Viscount and the Witch was born. Here's a bit about the book:

Eleven years before they were framed for the murder of a king, before even assuming the title of Riyria, Royce Melborn and Hadrian Blackwater were practically strangers. Unlikely associates, this cynical thief and idealist swordsman, were just learning how to work together as a team. In this standalone first installment of The Riyria Chronicles, Royce is determined to teach his naive partner a lesson about good deeds. Join Royce and Hadrian in this short story (5,400 words) about one of their earliest adventures.

Eleven years before they were framed for the murder of a king, before even assuming the title of Riyria, Royce Melborn and Hadrian Blackwater were practically strangers. Unlikely associates, this cynical thief and idealist swordsman, were just learning how to work together as a team. In this standalone first installment of The Riyria Chronicles, Royce is determined to teach his naive partner a lesson about good deeds. Join Royce and Hadrian in this short story (5,400 words) about one of their earliest adventures.

It just went live late yesterday on Amazon and already is on the Hottest New Releases for Historical Fantasy (#7) and Short Stories (#14). And while I hope people continue to buy it at the paltry $0.99 (as it will get Michael some Amazon visibility and possible recommendations for his Orbit books) we are not releasing this to make money.

Why are we releasing it?

To say thank you for all Michael's fans who has gotten him to this next stage in his writing careerTo have "something out there" that people can read while they waitTo hopefully give an "easy to digest" intro to new people to the seriesThe best way to say thanks is to make the book for free, but Amazon doesn't allow us to do this ($0.99 is the cheapest that we can list a book). But...hopefully they will "make it free" as they will price match other sites where the book is free (such as Smashwords). Usually a book has to have some "following" for them to do this so my hope is we'll get a few sales, get on Amazon's radar, then will price match to free.

This short is being released through Ridan Publishing (not Orbit) so we CAN make it free when bought direct. Here is a link where you can get your very own free copy.

I loved being reunited with my two favorite rogues. I hope you'll feel the same. Enjoy!

This is Robin (Michael's wife for those that don't know). I'm commandeering his blog to announce: The Viscount and the Witch. This is a little short story Michael wrote at my urging because...well as some may know I'm in love with Royce and Hadrian (sorry hun, but you know it's true) and I just can't get enough of them.

This is a strange time...the Ridan books are out-of-print and the Orbit books (although available for pre-order) won't be available for reading until Thanksgiving so, after three years, we have no books for sale ;-(

As we've both said, there will be no seventh book to the Riyria Revelations. That particular story wraps up completely in Percepliquis and to "tack on" another just isn't going to work (and no amount of needling will get Michael to do -- trust me on this).

But...Royce and Hadrian spent many years together before the event that happened starting in The Crown Conspiracy so I begged, pleaded, and offered "favors" to get a tale of the "early years" and hence The Viscount and the Witch was born. Here's a bit about the book:

Eleven years before they were framed for the murder of a king, before even assuming the title of Riyria, Royce Melborn and Hadrian Blackwater were practically strangers. Unlikely associates, this cynical thief and idealist swordsman, were just learning how to work together as a team. In this standalone first installment of The Riyria Chronicles, Royce is determined to teach his naive partner a lesson about good deeds. Join Royce and Hadrian in this short story (5,400 words) about one of their earliest adventures.

Eleven years before they were framed for the murder of a king, before even assuming the title of Riyria, Royce Melborn and Hadrian Blackwater were practically strangers. Unlikely associates, this cynical thief and idealist swordsman, were just learning how to work together as a team. In this standalone first installment of The Riyria Chronicles, Royce is determined to teach his naive partner a lesson about good deeds. Join Royce and Hadrian in this short story (5,400 words) about one of their earliest adventures.It just went live late yesterday on Amazon and already is on the Hottest New Releases for Historical Fantasy (#7) and Short Stories (#14). And while I hope people continue to buy it at the paltry $0.99 (as it will get Michael some Amazon visibility and possible recommendations for his Orbit books) we are not releasing this to make money.

Why are we releasing it?

To say thank you for all Michael's fans who has gotten him to this next stage in his writing careerTo have "something out there" that people can read while they waitTo hopefully give an "easy to digest" intro to new people to the seriesThe best way to say thanks is to make the book for free, but Amazon doesn't allow us to do this ($0.99 is the cheapest that we can list a book). But...hopefully they will "make it free" as they will price match other sites where the book is free (such as Smashwords). Usually a book has to have some "following" for them to do this so my hope is we'll get a few sales, get on Amazon's radar, then will price match to free.

This short is being released through Ridan Publishing (not Orbit) so we CAN make it free when bought direct. Here is a link where you can get your very own free copy.

I loved being reunited with my two favorite rogues. I hope you'll feel the same. Enjoy!

Published on September 30, 2011 07:37

September 28, 2011

One More Page

In case you haven't heard, I'm being published by Orbit, a subsidiary of Hachett, one of the traditional big six New York publishers. Currently most people know me as an ebook success story because that's where most of my books were sold. Ebooks made my career, but I still love bookstores. I bet you'd be hard-pressed to find an author who doesn't.

When I was first published, the small press who put out The Crown Conspiracy set me up with quite a few bookstore signings. Once I switched to print-on-demand this became more difficult and over the years I saw a shift in the mentality of many of the large chains and how they handled author's events. Even though the store managers at Borders loved the number of books I sold at each signing, they had to stop booking me because corporate handed down an edict restricting author signings. Many of the Barnes and Noble's I used to sign at have remodeled, adding more shelves, and now have no space for author signings. Not only could I not do my Orbit book launch at the store that launched the series, they also evicted my weekly writing group that met there for three years.

This has started me speculating on the future of bookstores. I think a lot of people have been doing that, mostly people in bookstores. I find this trend of big chains to increase the number of books in their stores at the expense of services, a bit of an odd strategy. What brick and mortar store can expect to offer a better selection than a virtual one? I've been to some awfully big bookstores, four-story behemoths and I find they almost never carry most of the titles I'm interested in—the ones I've seen reviewed online—the ones by independent authors. No matter how big the store, the selection of books are always the same. The same genres, the same authors. The new cutting-edge writers, who are breaking new ground, are missing from those shelves and, I expect, always will be. There are simply too many books being published each year for a physical store to house. Trying to keep up with a virtual store in a battle of selection is like bringing a knife to a nuclear war.

The one advantage a book store has over a virtual space is community interaction and the undeniable fact that people like being in bookstores. They enjoy going to them. They prefer the warm, bookish atmosphere that's like a library without any priggish rules. Unlike any other kind of store, you can usually get a cup of coffee, relax in a cushion chair, and spend all day sampling their wares. You can chat with employees about the new releases like kids do about new games or movies. And everyone can find something they enjoy, something that appeals to them, that they can get lost in.

Given this, I have to wonder why corporate managers are choosing to stuff their stores so full of books that there's no longer room for customers?

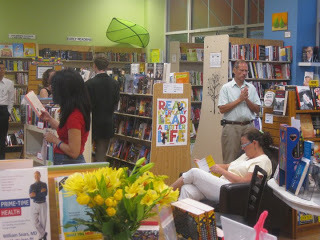

The Theft of Swords book release is coming up, and I wanted to have a party at a local store. As I mentioned, where I originally launched the series now can't accommodate an author event. I was wondering where I might hold the party—or if I would even have one. To my surprise I received an email out of the blue from someone who works at a store called One More Page.

Hi Michael! We are a new independent bookstore in Arlington--we opened in mid-January. A friend of store-owner Eileen McGervey forwarded to us a message you sent out in February about your new publishing deal with Orbit Books. Please keep us in mind when you hit the road and start doing press and promotional tours. We're just in your back yard, and we'd love to host you for an event, or sell books for you at any local off-site events.

Of course, with this deal, you're probably getting ready to move to New York! In any case, congratulations, and thanks for letting me introduce our nifty little bookstore. I could really relate to your invocation of "the little indie that could"!

A bookstore wrote to me? A bookstore contacted me and just threw their arms wide and invited me to hold whatever!

I had never heard of One More Page, but that was certainly about to change. Robin and I accepted an invitation by Terry Nebeker, whose intriguing title is, Author Whisperer, and rode over to this little bookstore hidden away on a business side street off of Washington Street, in Falls Church, Virginia. It is not a big place and its brand new—they opened this year. I had to ask myself who opens a bookstore in 2011, the year of the ebook? The year that killed Borders? It's like deciding that this is the time to invest in Wall Street. It turns out a woman by the name of Eileen McGervey did. A former marketing executive, Eileen apparently left that world to do something she felt she would enjoy more, something that would allow her time with her family—a world of wine, chocolate, and books. I've yet to meet Eileen, but I already envision her as a Willie Wonka of the literary world.

I had never heard of One More Page, but that was certainly about to change. Robin and I accepted an invitation by Terry Nebeker, whose intriguing title is, Author Whisperer, and rode over to this little bookstore hidden away on a business side street off of Washington Street, in Falls Church, Virginia. It is not a big place and its brand new—they opened this year. I had to ask myself who opens a bookstore in 2011, the year of the ebook? The year that killed Borders? It's like deciding that this is the time to invest in Wall Street. It turns out a woman by the name of Eileen McGervey did. A former marketing executive, Eileen apparently left that world to do something she felt she would enjoy more, something that would allow her time with her family—a world of wine, chocolate, and books. I've yet to meet Eileen, but I already envision her as a Willie Wonka of the literary world. Her store is a beautiful, quaint place with a few soft chairs, and plenty of books, but also plenty of space. Best off all, in some incredible, high-tech coup that has clearly taken all the other bookstores by surprise, One More Page has managed to invent the wheel. Okay, maybe they didn't invent the wheel, but they put them on the bottoms of the book display shelves so they can be wheeled out of the way for such things as book signings, and writers, and readers groups. This astounding advance in bookstore engineering has allowed them to do the impossible. In a space smaller than a chain store's coffee shop, they have created a retail space that can also allow for community events.

And they are making use of this.

Their website has a schedule of events, and not just a once a week children's story time, common to most stores and libraries. They have book club meetings, chocolate and wine tasting, author events, readings, discussions, critics-in-residence, baseball night, writer's groups, and…yes, children's story time. Their schedule is—pun intended—booked. And while they don't have a coffee shop in the store—they have a whole café right across the tiny side street.

Their website has a schedule of events, and not just a once a week children's story time, common to most stores and libraries. They have book club meetings, chocolate and wine tasting, author events, readings, discussions, critics-in-residence, baseball night, writer's groups, and…yes, children's story time. Their schedule is—pun intended—booked. And while they don't have a coffee shop in the store—they have a whole café right across the tiny side street. Will they be able to compete with the big stores on the block? With Amazon? Obviously not on their playing field. Yet I don't think that's their plan. Instead of trying to offer as many books as possible, One More Page offers a limited selection, but it appears to be a carefully chosen one. These are people who read. Their book buyer is Katie Fransen a grad student with a voracious appetite for books. How voracious? When I walked into their store and we were introduced for the first time—she knew me, and my books. That's never happened before. Usually, when I tell people I'm an author they ask, "Write anything I'd know?" to which I laugh and shake my head. But she knew about Riyria. She was a living breathing, female version of Myron Lanaklin.

Looking around at the moveable shelves, at the signs on the walls announcing dozens of up-coming events, listening to the passionate conversations the staff held with a constant stream of customers, hearing them instill a giggly exhilaration in others about the promise of a new book release, I had one thought running through my head—this is the future of bookstores. This is the place you can go to ask what you should be reading next. This is the friendly face you can trust to know what you like, to even set aside a copy for the next time you wander in. This is your own personal library, cared for by a staff who don't demand a weekly pay check from you, just the price of a book, a glass of wine, or a bit of chocolate now and then—and who can't appreciate something sweet and wonderful now and then.

And just to be clear, no one at One More Page has any idea I've written this post, and probably won't ever know, unless their in-house-Hermione-Granger, Katie Fransen, also reads my blog, but that might be beyond even her powers.

Published on September 28, 2011 09:09

September 24, 2011

Writing Advice 14 — Multitasking

I once had a discussion with a neighbor about writing. He was a fan of books that he said, "challenged him." Books that he had to work to get through and when he was done, never completely explained what happened. He liked the idea that the author left that task to him. To me however, this sounds a bit like hiring a painter to paint your house, only to have him show up with paint, ladders, and brushes saying, "Here you go, have fun." I have no doubt there are many others who agree with my neighbor—some may enjoy the experience of painting their home—but I also know dude ranchers out west can hardly believe they can get city-folk to pay money to do their work for them.

As an author, I feel it is my job to do the work, not the reader. As such I try to make reading my stories as easy and enjoyable as possible, and one of those ways is to not make a reader read one word more than is necessary. Whether you like Hemingway or not, his minimalist style was a necessary counterpoint to a literary tradition of poetically bloated books. I personally feel Hemingway went too far, carrying his idea to an extreme that hinders the art that words can create, but his idea is a sound one—take out the unnecessary words.

Bob sat down.

This is a pretty simple sentence. There are only three words, but nevertheless it is wordy because one of those words is not only unnecessary, it's redundant. Can you find it?

So then, Bob went back into his room to get his wallet, and then he ran back out to the car again.

Lots of unnecessary words here.

Better yet: Bob got his wallet from his room.

Trimming the fat in this way, makes prose cleaner, tighter, easier to read, and more powerful, but you can do more than just cut excess words. You can multitask.

Multitasking is doing more than one thing at the same time. Applied to writing, it is saying more than one thing with the same words. Why make a reader read a whole paragraph describing Harvey who is visiting Bob and then another whole paragraph describing Bob's house. Wouldn't it be better to do both at the same time?

The house was a two-story colonial painted yellow with green shutters, and a brick chimney. It sat on a quarter acre lot that sloped to the left. There was a maple tree in the front and a pair of birch trees in the back. A vegetable garden could be seen to the left of the house, and a swing set to the right, and the garage door was open reveling the back of Bob's car.

Harvey did not live in as nice a home as Bob. In comparison, Harvey lived in a dump. The reason was obvious, Bob made a lot more money than Harvey and he could afford to have the nicer things in life. When people asked Harvey about Bob, Harvey was always polite, saying Bob was a great guy, but he actually hated Bob, not because Bob had ever done anything to deserve his hate, but because Bob always got what he wanted and Harvey never did.

In the above two paragraphs I described Bob's house and then Harvey and how Harvey feels about Bob. But let's see if we can do all three at the same time, and with less Telling.

Bob's house was one of those perfect colonials always pictured on the cover of magazines that Harvey could only afford to look at. It was painted vomit yellow with showy green shutters, and a brick chimney built with all the craftsmanship of a robot. On the side was one of those huge wooden playgrounds parents appeased their kids with. On the other side was a vegetable garden. It was well kept. Bob probably had illegals working it at night so he could stand out there on weekends waving at his neighbors. Bob's garage door was open and Harvey could see a newly waxed Mercedes. Harvey guessed an American car was just not good enough for old Bob.

In the first paragraph, the house is described objectively, in the last it is infused with Harvey's negative PoV. The result is how Harvey sees the house tells you just as much about Harvey as it does about Bob, Bob's house, and the two men's relationship.

Using PoV in combination with description can result in delivering twice, to three times the information, to a reader with far less words. If done well, you can describe a place, a subject character, and the PoV character all at the same time.

Danny was always a stickler for precision, even his pens were lined up on his desk an equal distance apart. That's what made him such a good pilot, it also made him a pain in the ass to room with—particularly in zero-g.

In these two sentences I managed to explain that the scene takes place in Danny's office, and that it was very neat. I further related that Danny is a good pilot, and that he is a very orderly person who pays attention to even tiny details and that this assists in helping him with his job as a pilot. I also revealed that Danny is an astronaut. In addition, I revealed that the PoV character respects Danny, but also finds his obsession with orderliness irritating. I also revealed that the two characters have both been in space on the same mission. We can also assume Danny was the pilot of that mission. All this is added simply by playing with the PoV in conjunction with the description.

The idea is to focus on the primary task of describing the setting, or the subject person, but also, through how that description is written, reveal who the PoV character is by showing how that person interprets what they experience. A dog can be a cute puppy, or a mangy mutt. A woman can be hot, or a whore. A lake can be serene, or a death trap. A birthday cake can be festive, or one more nail in the coffin.

You can also apply this same idea to the plot. Don't write a chapter or even a scene merely to demonstrate that a character is smart, or evil, and don't write a scene where a character walks though a town, just to describe the town. Don't even do both at the same time. Always make certain that you have a legitimate plot point, an event that advances the story and then around that add the character and setting aspects. If the character has to see a specific car to advance the plot, have him wandering the streets looking so you can also describe the town, and have his method of searching reveal his intelligence. Always do more than one thing, or you are wasting space and your reader's time.

Let's go back to the now infamous Seven-11 milk buying scene. If you were to write the scene where the PoV character walks in and buys a gallon of milk, how differently would you describe the store and its clerk, if in the first instance your PoV character was an urban vampire, like Angel, trying to kick the habit of killing humans, and in the second he was Sherlock Holmes on his way home after a tough day working a frustrating case? Do you think that you could adequately illustrate who the main character is without using any descriptions of the PoV character and restricting yourself to only using the description of the store and clerk?

Here then is another homework assignment. Try writing those two scenes. No more than a page each. But under no circumstance are you allowed to provide any direct descriptions of the PoV characters. You can't say, "as a vampire, he didn't really like milk…" You can only reveal the PoV character by how they view the world around them—by their unique PoV.

After you write them, give each to a friend to read and see if they can figure out who the PoV characters are. If you don't like Angel and Holmes pick others, someone the person reading will know. You can present it like, "Read this and tell me who you think the main characters are—they are famous people who may or may not be fictitious." For more fun invite more than one person to read them and have them discuss who they think the main characters are.

If anyone does this, please leave a comment letting me know how it went.

That's the bell. No pushing or shoving.

Next week: How to Begin

Published on September 24, 2011 18:45

September 22, 2011

A Frustrated Muse

I know, the title of this sounds a bit like the name of someone's poetry blog, or perhaps a novel about an artist obsessed with a woman he had seen briefly in a crowd. Actually, it's the answer to a question that I'm frequently asked.

I suspect a lot of authors get this question in interviews or while at conventions and signings. It's one that stumped me for a while—one that took far more time to figure out than I expected. It seems like a very simple inquiry, but those are often the hardest to answer. Why do people laugh? How high is up? This question follows in those traditions, but unlike ones that suggest a need for specialized education or research to attempt an answer, this question appears to be one I should know immediately. It is a question more like: what's your favorite color? The question is deceptively complex, and I saw it as a potential trap until recently when I finally landed on a satisfactory answer. What I came up with may not be the answer, it's just mine. So what's the question?

Where do you get your ideas from?

The tricky part is that the question isn't where did you get this idea from, that would be hard enough, but what it's asking is where do all your ideas stem from. The real answer is, "I don't know. It just sort of came to me."

I mean, why did I decide on pizza for lunch? Why did I wear the blue shirt rather than the green one today? And why is there no emote for shrug? These are impossible questions, but while no one really cares why I ate pizza, except maybe the pizzeria's marketing department, and few are interested in my shirt color, where my ideas as an author come from are clearly a hot topic.

The answer, while mildly interesting to readers trying to get a better understand of their author, is taken more seriously by aspiring writers. They may consider this a well that they might like to find and dip their cup in, I guess. I mention this because the follow-up question is usually: how do you deal with writer's block or a lack of ideas?

I think those asking the question make a fair number of assumptions. Romance novelists are hopeless romantics who never found true love. Science fiction authors wished they could be astronauts. One has to ask, if such a theory holds true, what would that make H.P Lovecraft or Poe? People like to get at the truth. They like to figure out the mechanics behind the magic trick. How is it done? What caused it? Can it be duplicated? My conclusion is that sometimes what appears to be magic, really is magic. Maybe one day scientists will figure out the workings of the human brain enough to explain the creation of an idea by some mathematical formula, but for now there is no explanation other than magic—or as I call it: A Frustrated Muse.

A muse is a goddess in Greek mythology who inspires creation. Daemons are similar, although less grandiose than muses. While still Greek, they are more popular in Roman culture. But both concepts are the same—something other than the artist provides the idea, the spark, or since this is the modern era, the light bulb. In his recent book Incognito, David Eagleman suggests it's our own sub-conscious. So whichever way you look at it, the idea appears to come out of nowhere.

I'm sure this is not the answer that people want, particularly those trying to replicate the process. So how do you find a muse or rouse your sub-conscious? As it turns out, this is easier than you might think.

You piss them off.

When I was trying to get published, I knew that the best chance I would have is if I could get my wife to help. Being a high school valedictorian with a degree in engineering, who went from a grunt programmer to president of a software company in four short years, you can see she tips the over-achiever scales and has a good mind for business. I knew if I asked her to help she might resist, or put out a half-hearted effort. After all she is a busy person and has other things to do. Knowing her as I do, I also figured that if I made an intentionally pathetic attempt she would be appalled, shove me aside, and demonstrate how to do it right. My theory worked and today I am a published author as a result.

Just imagine yourself watching someone struggle with a problem that you find simplistic or second-nature. Desires to demonstrate your skill, irritation at watching them fail, or compassion at their frustrations will eventfully motivate you to take action. I think the same principal comes into play with those muses and daemons. When you write, she is forced to sit by, looking over your shoulder, watching you screw up again and again. It's got to be frustrating. You can almost imagine her doing repeated facepalms, shaking her head, or muttering obscenities under her breath. The words moron and hopeless may slip out. You hear them, not audibly of course but inside your mind, and it makes you want to give up. Most do. The true basket-cases ignore the insults and keep pressing keys. You keep struggling to create interesting characters, landscapes, and emotionally compelling plots…and keep failing.

Unbeknownst to you, you are also torturing your muse. Stop it! she cries, but you press on because you can't stop. You're a writer, even if no one cares, even if everything you put out is contrived, weak, clichéd and utterly hopeless, it's who you are, and you can't stop trying anymore than you can stop breathing. Try holding your breath—you'll just pass out and start breathing again. Muses try to inspire you to use a plastic bag and a rubber band next time, only it doesn't work. You just keep writing—badly. Copying others, imitating styles, you're foolishly mired in being a mirror.

Then, one day the muse just can't take it anymore. Uncle! You hear the faint whimper. She just has to make the pain stop. The endless parade of ghastly words must be fought. And if you won't give up, then she will.

Here. An idea flares.

In mid-sentence your typing pauses, stunned. Whoa. That's good! Fingers race. Words pour. It is as if someone is whispering in your ear. The whispering stops. You trail off, staring at the wall.

Oh for heaven sake! Really? You can't take it from there?

More whispering and the words come again. When you're done you're breathless, exhausted and have no idea of the time. What just happened? How did you do that? Will you ever be able to do it again?

The next time you write the words don't flow and you're stuck again. Despair grips you. Eventually you just start typing miserably again. Whatever it was that you had has been lost. You're hopeless again. The magic must have been just a fluke. But you've broken the will of your muse. She tries to resist, but each time you hammer away it takes less to frustrate them into helping. Her fight is gone, and they relent faster and with more frequency. The more you write, the less she resists. If you take a vacation, you let your muse rest. You give her time to recover and the next time you write she has the strength to rebel. Writer's block can be as simple as letting a muse catch her breath.

This is why writers are encouraged to write every day. This is why even if you don't know what to write, you just start typing until it comes to you. This is why muses and daemons hate NaNoWrMo.

Whether it is a muse, a daemon, or your sub-conscious, ideas come from frustration, from the need to do something the "right" way, or say what isn't being said. This is the heart of passion, the drive of desire that gives birth to that spark, that light bulb—that idea that will prompt others to come to you one day and ask: where do you get your ideas from?

At this point, the weary head of the battered and beaten muse will lift with anticipation of recognition and listen carefully, and you will say…"I don't know. It just sort of came to me."

(This post was originally published on Jon Sprunk's blog about two months ago when I guest blogged. I reprinted it here for those who missed it, and so I know where to find it again.)

Published on September 22, 2011 07:30