Carol Newman Cronin's Blog, page 55

January 17, 2014

Eight Bells: Robert Otis Bigelow

From the time I was old enough to ride a bike until I graduated from college, I spent every spare summer moment I could at the Woods Hole Yacht Club. I had many friends there, but one of the best was Robert Otis Bigelow.

Bob was a local racing hotshot, so when he asked me to sail a Knockabout race with him, I was just thrilled. Even as a very green ten year old I understood that this was a big opportunity—and an honor.

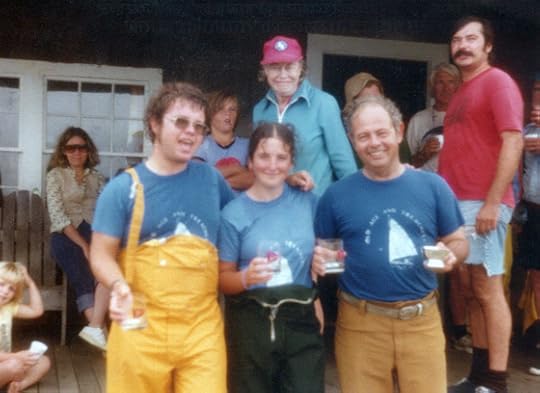

John Bigelow, me, and Bob Bigelow collect our loot after winning the Labor Day regatta, circa 1977.

I don’t remember who the other member of our crew was the first time I sailed on Blue Jean. But I do remember my first lesson from Bob—because he took time out from trying to win to explain a basic fact of sailboat racing. “See, he’s crossing ahead of us now,” he said, not as a teaching moment but just as a mention of what was going on around us. “The last time we came together we were ahead of him. There’s less current inshore—we’ve got to get in there.”

There were many. many more lessons over the next ten years, as I became part of the regular racing crew on Blue Jean. At thirteen he let me steer a weeknight series race, my very first taste of making my own mistakes. And by fifteen, I was taking his boat out with my own team. His belief in my basic ability to handle his carefully maintained boat made me a very loyal crew on the weekends—a win for all. As a teenager, it’s often easier to absorb lessons from a source outside your own family, and it’s also easier to learn basic sailboat racing on smaller boats. Bob made the most of his unique position to pass along his knowledge, and I soaked it up like a sponge.

On shore, Jean, Bob, John, Peggy, and Carol Bigelow all welcomed me into their family. I spent so much time at their house the summer I was fifteen that when my dad ran into Bob at the Yacht Club one afternoon, they joked about who should be paying for my college tuition in a few years.

And I wasn’t the only Bigelow adoptee. Their house was a meeting place for neighbors of all ages, brought together by our common love of racing small sailboats. Seated around the picnic table that was the social center of the house, I remember a lot of laughter, and a sense of community that easily bridged the many generation gaps. Everyone who came through the door was welcomed—especially if they brought a story to share.

Bob loved to tell stories about the twists and turns of fate. Whenever Yacht Club history came up, he’d tell the tale of taking over as Commodore in 1954, just before the clubhouse was demolished by Hurricane Carol. He never let us forget that the Three Mile Island disaster struck on his own 50th birthday. (Bob worked in the nuclear power industry.) And then there was the best twist of all, about how he and Jean met after being paired up as the two shortest members of a three-couple blind date. “Height is destiny,” he would crow, decades of happy marriage later. I wish he’d written his memoirs, since I’m sure I’ve forgotten (or never heard) some of the best tales he had to tell.

I first realized how much I’d learned from Bob when I started sailing in college. The priorities were much different racing lighter boats, especially on short courses that weren’t skewed by strong currents. But the tactics, strategy, and communication were the same.

He also passed along his drive to win, a deep-rooted determination that never was allowed to override sportsmanship. By example, he showed me how to learn from my mistakes, and that little things (like remembering to bring beer, and team T-shirts that read “Old Age and Treachery”) mean a lot.

I never thanked him directly for all his valuable lessons. But the Cape Cod Times passed along the message—and gave him some press of his own. An edition that came out during the 2004 Olympics showed a picture of my Olympic Yngling team on the front page, with a picture of Bob right below it; he was identified as my sailing mentor. “He never failed to answer any question I could think of,” I told the reporter. (Bob’s photo is missing from the online version, unfortunately.)

My favorite part of the article comes toward the end, when Bob admits his skepticism about my push toward such a lofty goal as the Olympics:

“I thought, be realistic,” he said. But now, he’s convinced. “Clearly, I wasn’t the one being realistic,” he said. “I didn’t think it was going to evolve to this level.” Sometimes mentors can’t see how fine a base they’ve built.

I had several other teachers along the way, including my own parents. But Bob’s lessons built an early and solid foundation of both skill and attitude. And that foundation took me much farther than either of us ever imagined back in 1974, when we were tacking upwind trying to figure out if we were behind or ahead.

Sail on, Robert O. Your memory and your lessons live on in the many, many lives you touched.

January 10, 2014

Losing the Belly Fire: Olympic Retirement

The morning of February 6, 2007 is etched in my memory. Pulling out of the Olympic Sailing Center in Miami with my Olympic boat in tow behind me, I turned right to head north. Next stop: a snow-covered New England driveway, 1500 miles away.

I’d driven the boat home before, but never in February. And never, ever with tears blinding me to the road ahead.

For the previous six years, my Olympic dream had propelled me forward, pushing me to ask for money, set up housing, pack boats into containers, and oh yeah, go sailing. All so we could find the extra ounce of speed we needed to look smart at the next event.

And I’d decided to walk away from all of it.

The 2004 Olympics in Athens weren’t such a light air event after all, at least for two days of the Yngling event. Photo: Daniel Forster

The life of an elite athlete has a pure focus on performance, and everything else that consumes normal people’s days and weeks—home life, casual friendships, job, hobbies, vacations—is burned away by an inner fire. No one who hasn’t lived it can possibly understand the mindset of living, eating, and breathing competitive sport.

And while we’re living and eating and breathing it, that life is all we can see. In the spring of 2004, weaving my way across a boat park teeming with Olympic sailors and the best equipment in the world, I remember thinking: How could anyone ever walk away from this?

But less than three years later, I did walk away. Because I’d realized that trying to keep up with an increasingly sophisticated and time-consuming regatta and training schedule was eating me up inside. I’d gone from a fire in my belly to a gut-burn of anxiety. It was time to step off the Olympic merry-go-round.

I knew it was the right decision, because I no longer had the drive to compete with the best in the world. And I didn’t want to make a half-hearted effort just to avoid quitting.

But it was still really hard to walk away, drive home, sell my two boats, and inform the people that mattered (not necessarily in that order). I was responsible for the dreams of others, too, and it meant disappointing teammates and coaches who’d invested time and money in my ability to claw back to the top again. They couldn’t feel that absent belly fire, and I couldn’t explain where it had gone. All I could say was that it was time for me to retire.

This all came back to me this morning, when I read Anna Tunnicliffe’s announcement that she was retiring from Olympic sailing. Anna has had a much more impressive sailing career than I ever did, which makes her decision even harder: the landing is softer when there’s not as far to fall. And of course she handled it with the perfect mix of humility, grace and dignity. Read her entire retirement announcement.

I’m sure Anna won’t regret this, even as we her fans will miss watching her inspire others with her 4Ds (Dream, Desire, Dedication, and Discipline). And six years from now, hopefully she will see (as I do now) that the belly fire that once ignited our Olympic dreams doesn’t die; it just transfers its heat to new passions and fresh challenges, beyond the world of sailboat racing. That may be harder to fit into a sound bite than “I want to go to the Olympics,” but it’s just as satisfying in its own way.

Good luck to Anna, and to all who look into their hearts and realize it’s time to move on. Retiring is hard, but without that fire in your belly, it’s also the right thing to do.

December 18, 2013

Holiday Book List 2013

I only reviewed two books this year, though I’ve enjoyed many more. Here’s a short holiday book list to finish off 2013.

Spilled Coffee

Authorly jealousy is the sign of a good book, and I had it for Uncharted, Bridget Chicoine’s first novel. And even though there is less boat repair in her second book, Spilled Coffee, I admit to a certain amount of jealousy for its excellent imagery. With constant steps back into the past (marked by a stopwatch picon) and a constant drip of information about the tragedy that’s still affecting the present, this one drew me in too.

Best of all, there’s more available from Chicoine: Portrait of a Girl Running and Portrait of a Protégé both came out in the fall of 2013. They sharethe same protagonist, Leila, but can be read independently (although knowing the backstory from Girl Running does enrich the reading of Protégé). More details are available on Chicoine’s blog.

Powder Burn

I don’t think I would’ve read this snowboarding thriller if I didn’t know the author, Mark Chisnell. But I’m very glad I did; the twists, turns, and details of a remote country in the Himalayas did what fiction does best; took me somewhere I’ve never been and let me walk around, seeing the world through the eyes of Sam, a self-described “glass-half-full kind of girl.” Visit Mark Chisnell’s blog for a full list of his titles.

And now it’s time for some last minute holiday shopping! Best wishes for a great holiday season.

November 6, 2013

Books Don’t Change, but the World Did

For the past few months, I’ve been rereading some of the old favorites that crowd my bookshelves. In between more “novel” novels, I’ve consumed the following for a second time: The Coffee Trader (David Liss), The Emperor’s Children (Claire Messud), The Post-Birthday World (Lionel Shriver), The House at Riverton (Kate Morton), and Coyote Heart (Paula Margulies). And even though these books don’t have much in common, those second readings were all surprisingly different from the first.

Windmills, like books, are still around to remind us of how much the world has changed.

Now you might assume that’s because I remember what happens, but don’t give my memory more credit than it deserves. For better or worse, I don’t retain much of what I read for pleasure, the best form of Alzheimer’s: only a few years later, I can reread more complicated plots with only a vague sense of familiarity.

What’s different is the world. The Way We Live Now changes so quickly that we now need books to remind us of how it was way back in, say, 2005. Websites can be updated, but print remains the same for eternity. So a reference to a mobile telephone as an unnecessary and annoying luxury rather than as a lifeline and ever-present companion now read as quaintly old-fashioned. On my first read, those same references would’ve left me nodding my head in agreement.

It’s not just technology, though that’s the most obvious change. How we perceive food, transportation, energy, and recycling—even books—has changed too. And every question, decision, and discussion seems to lead us to a screen and some kind of Google search. Who knows how we’ll be gathering information in 2015?

The book that seemed the most similar on a second read was The Coffee Trader, set in 17th century Amsterdam. My perception of that era, buried deep in history, hasn’t changed dramatically in the past few years. The others, with their various “contemporary” settings, definitely read differently only a few years later. Our world is changing so fast now that even two year old assumptions about how humans interact read like they took place on a different planet.

Which leaves me wondering: How do we write about our own times in a way that won’t seem terribly dated only a few years from now—a time span that (back in the late 20th century) was the minimum lead time for publishing a story? We are past the point where we can skirt references to digital devices, as I got away with in Oliver’s Surprise. Writing a present-day novel without someone picking up a mobile device would be like writing about a cave man who leaves for work without his club.

Phones will undoubtedly become “smarter” in the years ahead, and we will likely become even more dependent on screens of all shapes and sizes. But with any luck, books will stick around for a long time to come, if only to remind us on a second read what it was like “back then.”

And for another theory about time, read Editing Time.

October 23, 2013

The Glory of Morning

I love morning. The light and warmth build together as the sun climbs over land and water, and clouds drift or race overhead, changing colors with the sun angle. Windows on the west side of West Passage light up, winking across the Bay like square yellow jewels.

Paddling across a peaceful empty harbor is an instant escape from land life. Photo: PaulCroninStudios

Okay, okay… this photo was taken at sunset, not sunrise; there’s never anyone around at sunrise to take a picture, which is part of morning’s charm. But it still shares the peaceful pleasures of paddling across a wind-free harbor at the edges of the day. (It’s also a great example of the many visual treats that can be found at PaulCroninStudios.)

As sunrise gets later and later, it’s harder and harder to get out of bed in time to fit in a paddle before work. But for the past week, I’ve been using the same mantra: “How many more mornings will we have like this?” Warm enough even before the sun is properly up to get on the water, calm enough to enjoy the glide and watch my paddle slice into the water, dry enough that I don’t have to paddle too hard to stay warm.

Ah, fall; so much of its glory is in the knowledge that it won’t last.

Just like the glory of morning.

October 11, 2013

America’s Cup: Rod’s Wisdom

Rod Davis is a genius.

How do I know? Because his writing stands the test of time. And these days, that’s a dying art.

Most online stories are published and forgotten within a week, though they can be tracked down (and updated) as far into the future as the Internet is available. Magazine articles must be written months before they are published—and once in print, might as well be carved in stone. Typos, statements, and opinions are all locked in, fodder for future Monday morning quarterbacks.

Our fast-changing world may well have tilted on its axis by the time an audience digests our printed words. Take Sailing World’s special issue on the America’s Cup. Wonderful as it was from cover to cover, the words represented the last voices from a world before Bart Simpson’s tragic death.

In contrast, Rod Davis consciously writes for that unknown future. His October 2013 column in Seahorse, Match Planning, starts out: “You’re reading this knowing the answer, whereas I currently don’t.”

The question was whether Team New Zealand would win the America’s Cup, and Rod had more than a passing interest in the answer: he was in the final preparations of coaching the Kiwis when he wrote the article.

I didn’t know the answer yet either, the first time I read it. We were, in hindsight, settling into “phase one” of the long event. Rod’s team still had the faster boat—and they still looked like the inevitable winners.

Reading it again after it was all finally over, knowing I’d been wrong about the “answer”, everything in the piece still held true. Yes, the Cup was decided by “raw speed around the course.” And yes, there were few passing lanes at the bottom of the course. Here’s his most prescient statement: “A big one that we don’t know is the relative speed between the boats.”

By taking his own advice, “Play for the now,” Rod could be clear about the plan long before he knew the outcome. He also includes some great advice on how to deal with big event stress. Here’s my favorite quote: “Don’t try to step up a level for the big one. Do just what we have been doing and what got you to where you are.”

I still remember how hard it was to keep on track at the Olympics, almost ten years ago. Suddenly everyone was paying attention, knowing this was what we’d spent years preparing for—and beyond the event was a gaping cliff of “after” that depended (I thought) on the results. Now I know that life would become even better and richer in spite of a disappointing result. But at the time, it was easy to confuse “give it our all” with the mistake of “step up a level.”

So thanks, Rod, for the wisdom. And good luck with your own return to normalcy, now that we all know the results of that amazing regatta in San Francisco Bay. I can’t wait to read your next story.

And if you don’t subscribe to Seahorse Magazine, Rod’s article isn’t the only thing you missed.

September 12, 2013

The Write Question

If you run into me this fall, please don’t ask, “Are you writing a new book?” (or worse yet, “have you published a new book?”)

The question I like better these days is,“Have you been doing any writing?”

Because the answer to that question is a definite YES.

I’m writing blogs for boats.com. I’m even writing a few reviews and longer articles. And I’m keeping up (almost) with blog posts here as well, Where Books Meet Boats.

What I’m not writing at the moment is fiction.

I’m sure the voices in my head will return, crying to have their stories told. I’ll build a sculpture of words, and then carve a story out of it. And once that happens, I’ll welcome the next time someone asks “Are you writing a new book?” Because that’s the perfect launchpad to describe whatever the new story is about to become.

But for now I’m challenged by non-fiction, by testing iPad cases, reviewing the occasional sailboat,and finding videos manic enough to attract viewers on Manic Mondays. I’m also trying to bring together various specialty groups who all need to Share the Water. Teaching newbies about the joys of paddleboarding and sailing. And trolling through our incredibly rich archives (with posts dating back through the Internet ages) to dig out something worthy of tweaking into a fresh post.

When I have time, I’m even learning to edit video. And there’s plenty of storytelling in that as well.

Fall is traditionally my most creative season, so we’ll see if any new characters pop their head out to be noticed. If not, I have plenty of real life “characters” to entertain me. And for now, at least, that’s enough.

September 5, 2013

Growing Older, Not Up

I’ve long subscribed to the theory (which is also a great song by Jimmy Buffett) that growing older does not have to mean growing up. I’ve tried to keep my youthful attitude, learning and challenging myself both on and off the water.

Sailing the 2011 regatta with teammates who remain great friends: Kim Couranz, Margaret Podlich, Karina Vogen.

And then one of my favorite regattas is cancelled, and I realize if I were really still a kid, it would look like a big disappointment instead of a step forward.

I grew up with the Rolex International Women’s Keelboat Championship, at least as a sailor. My first event in 1991 marked my entry into high level racing; in those days it was a “must-do” for women looking to improve as sailors. After that I never missed it, though I did upgrade my position from bow, to middle, and eventually all the way back to the helm. It was a great cross-training event while we were preparing for the Olympics. And then it became a great chance to sail against the next generation of Olympians, on a fairly even playing field.

My last event, in 2011, turned out to be the final event of that name, though it’s possible some offspring regatta will eventually replace it. The 2013 regatta was scheduled for this week, but due to lack of interest it was cancelled at the last minute.

If I were still trying to gain experience, I’d be really bummed that this biennial celebration of women’s sailing is no more. Instead, I’m celebrating that today’s hopefuls have the opportunity for top-level international competition more than once every two years. Those coming up through the ranks now have so many options that the Rolex was getting lost in a sea of sailing. And that’s a good thing.

So I guess I have to admit to growing up after all, along with the Rolex. We both had our day, and now we both are sailing off to other adventures. It was a great ride, and I won’t let go of the many great friendships and teammates that came my way in the past twenty years. But I have already let go of the event that brought us all together. The Rolex is dead, long live the Rolex.

August 20, 2013

Tourist Season: The End of the Road

It happens every summer, as predictably as a Narragansett Bay seabreeze: the tourists arrive.

They don’t throng on our island in the volume of nearby Newport, but they still change the atmosphere. Out of state license plates. Clogged roads. Traffic patterns changed by cars driving below the speed limit. And strangers asking strange questions, like the one I got a few days ago: “If I follow this street, where does it take me?”

We grin, tolerate, or swear at them depending as much on our own mood as on their behavior—which is, after all, quite predictable. (More on that in a moment.) We joke that “If they call it tourist season, why can’t we shoot them?” And all the while, the downtown vendors happily take their money, squirreling away enough income to make it through the long quiet winter ahead.

And then we go on vacation ourselves, and the tourist flip flop is suddenly and completely on the other foot.

If I lived here, I wouldn’t appreciate the view the way I did on vacation.

Last weekend in Maine, I laughed about our slow pace over unfamiliar twisting roads. I told the locals who piled up behind me “sorry” (though they didn’t hear it), knowing they were gritting their teeth at my 30 mph in a 40 mph zone. Forgive me, I wanted to tell the driver of the pickup who blasted by as soon as there was a safe place to pass. We are just enjoying the spectacular view, the one you take for granted, the one you don’t even see anymore. And besides, we’re not exactly sure if our turn will be around this bend, or the next. Or even the one after that. We’re now the ones with the out of state plates, clogging your roads and changing your traffic patterns—sorry.

Going on vacation morphs us from local to tourist, across that insurmountable divide—between those who know the terrain so well they don’t even see it, and those who slow down to drink in the view.

It seems so obvious why tourists drive slowly, once we become tourists ourselves. But back at home, we still speed by our own spectacular vistas, on the way to somewhere important. Part of the luxury of being a local is knowing a view will still be there next week, next month, next season. Not so for the poor tourist, who has to get the fun done ASAP before going home.

Hence that strange question, only a few days after I had morphed back to local: “If I follow this street, where does it take me?” What she really wanted to know was: “Is there anything worth my time to see ahead, or should I turn around and go somewhere more interesting?”

There were so many possible answers to that question: “It takes you down a beautiful tree-lined street, all the way to the water.” “West.” “To my house.”

But here’s what I came out with instead, off the cuff and completely unintentional in its classic local cheek:

“Where does it take you? To the end of the road.”

July 31, 2013

Where Books Meet Boats: Situational Awareness

Recently I read Gary Jobson’s column in Sailing World about making your own luck through situational awareness. It sounds totally obvious: those who notice what’s off most people’s radar see opportunities others miss. (And then those others say afterward, “She was just lucky.”) In sailboat racing, it’s easy to see who has made big gains; scores are kept, and each competitor can see what the others are doing around the course.

In writing as in sailboat racing, situational awareness can help you see opportunities others miss.

Where those gains are not so obvious is in writing. We all know when we like a book, but we usually don’t notice all the details that are worked in, details that could’ve been left out because they aren’t doing the heavy lifting of moving the plot from point A to point B. And while most writers can tell a decent story, it’s those more subtle pieces of information we often remember long after we read the last page. Information that a writer with less situational awareness would miss.

Like sailboat racing, writing requires attention to craft. But I’m not sure that this situational awareness skill can really be learned in either case. You either see the wind filling up the course, or you don’t. And you either live with your characters full time, or you don’t. The character trivia that enriches our stories comes out of sitting together, quietly, like old friends rocking side by side on a summer porch. We need to understand their lives outside what happens on the page.

For me, “good writing” is when a tiny word or phrase is worked into a story that creates depth well beyond the scope of the specific detail. Sometimes I catch myself thinking, “That must’ve taken a lot of research to find”, and I might even wonder if it was worth the time for a one sentence aside. But added together, all those asides are what gives a piece its impact; it’s why we read, and why writing can’t really be replaced by watching, or anything else.

Gary Jobson is a writer as well as a sailor, so he probably makes his own luck in both arenas. The process, after all, is the same: widen your gaze, try to see something no one else sees, take the time (and develop the nerve) to follow your instinct as far as it leads. Only then can your ideas morph from idiotic time sink into regatta-winning advantage.