Carol Newman Cronin's Blog, page 51

June 9, 2016

Collaborative Editing: The Tools Don’t Matter

For the past few months, I’ve been working with a client creating and updating content for a new website. The goal is obvious: accurate and easily digested consumer-friendly information, which promotes the product without overselling. The process, though, is surprisingly opaque; how to efficiently organize content creation, fact checking, and removal of typos into a seamless flow, in order to include the widest possible variety of perspectives and editing visions? The more people involved, the more complicated the process will become—and the better the end result.

Ten years ago, we would’ve passed around each initial Word document, marking it up with “track changes” until none of us could read the actual text anymore, and updating the name from “content-v1” to “content-v2” and on up the list, until the inevitable “content-final”—which would, also inevitably, require a few more modifications before becoming truly final. Some would add their initials to the title too, to indicate the source of the latest edits, but that would quickly become cumbersome. And even if we had set up naming protocols in advance, there would likely be some hiccups along the way: is this really the latest version I’m working on? If so, where are my edits from five days ago?

Today, we pass around the link to each online document—which is both better and worse. Better, because it’s easy to revert to previous versions, see who made specific changes, and share with a large group by storing in a shared folder. Worse, because files stored on Google Drive have a tendency to disappear—especially when they are initially uploaded as Word docs (which don’t show up in search) and aren’t updated for a week or two. Even when files don’t disappear, the tools and menu options often change with the latest “upgrade.” (What I’ve learned about organizing files and folders on Google Drive is probably worthy of its own post…)

What I’ve come to realize is that the tools don’t matter: the only way to keep a collaborative editing project under control is to set a few basic rules at the very beginning. Here are some of the lessons I’ve learned from working through this process; maybe they will help you in your next editorial collaboration.

1. Start off with a set work flow. Even if it’s modified later, make sure everyone knows the process and who is responsible for each step.

2. Create a central spreadsheet where progress can be tracked. This should include each desired piece of content and its necessary work flow (eg. “content creation,” “fact check,” “final edit”), as well as the document’s link.

3. Have one central “librarian” who keeps track of files and progress (and sends out reminders when deadlines are missed). Google drive is a great way to share files, but it is surprisingly easy to lose things—especially when they’ve remained stagnant for a while.

4. Get the big ideas down first, and then refine them—while making sure the piece itself is doing its designated job. There’s no point in having someone fact check details that aren’t pertinent to the overall topic.

5. Think Goldilocks when sharing links and updates. Including everyone (especially through generic Google sharing emails) will lead to “doc blindness”, like the boy who cried “please edit this” once too often. Not sharing widely enough will obviously have the same end result: a file not seen by the key person who can help make it better.

Different people have different levels of comfort with “systems”, so in order to get the best input from the widest variety of perspectives it’s important to be a little flexible. If someone’s not working within the established system, there are two likely reasons: the first is that it hasn’t been clearly laid out. The second is that it’s not easy enough to be adopted quickly. Depending on how long a project’s time frame is, it may be easier to provide a workaround than to educate.

Collaborative editing leads to better content because the final version will reflect multiple perspectives and areas of expertise. And that’s what really matters—not the tools we use to make it happen.

June 2, 2016

3×5 Ways to Change the World

I’ve always been fascinated with infographics—even if I have trouble remembering the actual term. Using visual cues, they consciously focus on the most essential words of an idea, which sends them directly our brains—bypassing the kicking and screaming caused by punctuation and those “little” connector words and phrases. Usually our eyes skip right over those words anyway, even though we editors cringe when they actually go missing from a paragraph.

Here then is my first attempt at an infographic, designed to convey a few large and several rather small ideas. Enjoy, and please let me know what you think.

May 26, 2016

Letting Go of Our Kitchen Water View

Recently our water-side neighbors decided to build a two car garage. It will be a great addition for them, and it’s well within their rights. But I’m sure going to miss the tiny peep of a water view we used to have, between trees and rooflines, from the window over our kitchen sink.

Fortunately, we still have a view of the harbor from the front of the house—and from our second floor. That will help with those early morning winter decisions, when paddling is still a go/no-go question. So again, the kitchen water peep shouldn’t be a big deal. (And yes, I realize this is definitely what one friend would call a “first world problem.”)

And yet, without bemoaning our neighbors their choice (it’s going to be a really nice garage), I lament the loss of this small piece of horizon. Looking west has always been a key way to “see what’s coming” for me, and even though surprises certainly still sneak up, I imagine that I’m better prepared.

A quick glance at that tiny slice of harbor (while mindlessly doing the dishes) tells me so many things that losing it feels like I’ve put on horse blinders. Wind direction and strength is just the beginning; the color of the water’s surface and how it reflects the sky speaks volumes about water and air temperature, season, and what’s coming in the next few hours (at least weather-wise).

Other people seem to function just fine without a daily water peep or a westerly view. Me? I get antsy without that perspective. Even if it’s a small lake or pond or some duck puddle in the middle of nowhere, I feel calmest when I get a morning glance across a body of water. As long as it’s big enough to reflect the sky, it grants me the illusion of seeing what’s coming next.

Which means that I chose my travel sport well. No matter where in the world I go to sail, no matter how far inland I go or what the terrain is, I’ll get that water view as soon as I arrive at the boat park—and at the end of the day, that same perspective will be waiting to greet me, no matter how well or poorly the racing went. Maybe that’s why I’m often the first one to arrive, and sometimes the last to leave, storing up that water view until I return the next morning.

In a few more years, once two or three key trees grow a few more feet, we would probably have lost that kitchen water peep anyway—slowly, instead of overnight (with the erecting of a second story wall on that beautiful garage). And just as horses adjust to wearing blinders, I will surely get used to living without it. But every time I wash dishes, I’ll be trying to imagine what color the harbor is, and what that should tell me about the rest of my day.

No matter how great the view to the west, surprises will keep coming. And hopefully the past twenty years of observing that small piece of west-facing perspective have taught me enough to extrapolate what that water peep might be saying. If not, well—maybe I’ll just stop doing dishes.

May 19, 2016

Listening In, Outside

A few weeks ago I spent two days in Oxford, MD, on my first-ever dedicated fiction research trip. To be centrally located, I stayed at the Robert Morris Inn, which happens to be just across the street from the Tred Avon Yacht Club. But for once my focus was not on sailing—it was on the ferry.

One of the characters in my next book comes from here, and the ferry (which has run continuously since 1683) was a big part of her childhood.Her accent is subtle, but decidedly different than a New Englander’s, and several weeks ago I realized that I couldn’t hear it in my head, so I went to Oxford to listen. And then like all the best adventures, I came home with something completely unexpected.

As soon as I arrived, I realized that even off-season there aren’t too many locals in Oxford; it’s mostly a retirement and holiday community now. Wandering around town, admiring well-kept yards and white picket fences, I heard a variety of accents as shopkeepers and contractors polished and prepped for another busy tourist season. None sounded like I’d hoped. And of course the other Inn guests had all brought with them accents from somewhere else: DC, Boston, North Carolina, London.

That first afternoon, I stepped onto the ferry for the first time. As the only foot traffic passenger, I had a great chat with the deckhand, who was from… Michigan. But I learned a lot about the ferry boats and their owners from him during the ten minute ride across the Tred Avon River. And the view—even on a cold gray May afternoon—provided a waterside perspective on the town behind me.

It was when I stepped onto the dock in Bellevue that I finally heard the accent I’d been looking for: three Eastern Shore watermen stood near the stern of one crabber, talking about their day. That’s it! I thought. But how could I transform myself from a lone tourist on the dock to a fly on the wall? I couldn’t just stand there, visibly eavesdropping. And I certainly couldn’t come clean (“Hello, I’m writing a book and I really want to listen to your accents; please continue talking naturally”); any outside interference would instantly change or even shut down the conversation. It made me wish I had a fishing rod with me, just so I could look busy while hovering within earshot.

Eavesdropping is easy at a restaurant, or in a bar: you just cock your ear toward the accents while looking at the TV, or while pretending to talk with your companion (who, of course, was tipped off in advance about your real purpose). On a ferry dock by myself, there were absolutely no excuses to linger. I tried watching the abnormally high tide pushing at the pilings, but how long could I stare at something so natural without those three guys wondering what I was really doing?

Instead I wandered up the dock as slowly as I could, and then wandered back down again. Eventually I asked one of the watermen a question, and his tone instantly grew more formal and clipped. “Talk amongst yourselves again,” I wanted to say. But their conversation had already come to its natural conclusion, and natural was of course what I was looking for.

The next morning, I went for another walk around Oxford. And with time to linger and the open mind of a dedicated research adventure, I spotted an oyster shell that somehow seemed significant. From there it was a quick leap to its place in the book, which taught me something completely new about my Oxford-born character. Tucking the shell into my pocket, I went “home” to the Inn for another great breakfast. Sometimes we come to a place to listen—and leave with a beach shell that many others have passed over.

Living with a novelist’s eye (and ear) makes the world even more vivid, especially when we stumble onto something quite small that leads to the next big idea. I may not have yet figured out everything about this character (or how to eavesdrop on an outside conversation), but I’ve definitely learned to spot brainstorms when they appear—even if the spark shows up in a completely unexpected way.

May 12, 2016

What Makes a Champion?

Last week I had the honor of hearing America’s Cup winning skipper Jimmy Spithill talk to the 2016 Olympic Sailing Team and its supporters. Jimmy has never been to the Olympics, but he is certainly qualified to talk about becoming a champion, which is arguably one of the most important (and most easily overlooked) aspects of Games preparation.

Jimmy Spithill talks to US Olympic Sailing Team and supporters about being a good teammate. Photo courtesy Will Ricketson/USSailing Team Sperry

Jimmy chose as his starting point the most humiliating story possible. In 2012, on the seventh day of sailing their brand new AC72, he said to his team, “Let’s go upwind one more time.” That regrettable decision eventually led to a very public capsize under the Golden Gate Bridge and the eventual breakup of both boat and wing—only ten months before the 2013 America’s Cup began. Fortunately, no lives were lost.

Jimmy wasn’t telling this story because it was so dramatic, though the video footage certainly captured the danger and despair of losing a boat. He told it because campaigns, he says, always have a defining moment, and that’s what the capsize and boat break up turned out to be for Team Oracle. The way the team pulled together after that disaster made their historic comeback possible ten months later, because even with just one race to go, they all truly believed they could still win the America’s Cup.

Jimmy never made it sound like a foregone—if surprising—conclusion: that losing a boat could help them win the Auld Mug. Instead he talked about growing from challenges. All teams have them, he reminds us: the only choice is how you respond.

High Performance Director Charlie McKee was once an America’s Cup teammate of Jimmy’s, and during his introduction he identified Jimmy’s greatest strength: balancing the ego that keeps him believing he can win with the larger perspective of being a team player—which keeps that ego in check. And later on, Jimmy hammered that same point home: doing whatever you can to make your teammates better is the easiest way to become a champion.

It’s almost seems like a contradiction, that focusing on the team helps us grow as individuals, but his theory resonates with me. When I focus on myself, that’s usually a recipe for disaster. When I focus on working better with those around me and trying to help others improve, I get stronger and better.

The way Jimmy made his big point (that difficult times are the defining moments that make or break teams) also showed balance between ego and team. He managed to use video to its best purpose: not as an escape from the hard work of public speaking, but as a visual reinforcement of the story he’d chosen. Of course it helps to have a video crew following your every move, and an editing team to splice together hours of footage into a few minutes of dramatic highlights. But how to use such resources to their best advantage is a personal choice, and I certainly came away with a new perspective on that famous boat breakup—and the even more famous comeback.

Being comfortable in the public eye is one of the many challenges of becoming an Olympian. And I like to think that our 2016 Olympic Sailing Team is a little better prepared now to take on that challenge, as well as the many others that lie ahead, after hearing champion Jimmy Spithill share some words of wisdom.

Being a good teammate is definitely easier said than done, but so is becoming a champion.

May 5, 2016

Author Lessons from Spotlight

A few weeks ago I finally watched Spotlight (the Oscar-winning film about the Pulitzer-winning Boston Globe investigation into the abuse covered up by the Boston Archdiocese). I’m usually rather oblivious to the annual Oscar flurry, but last October I’d heard a Fresh Air interview with the film’s director, Tom McCarthy, and the investigation’s director, Walter Robinson. No matter what Hollywood thought, I wanted to see the film for myself.

Michael Keaton plays Reporter Walter Robinson. To watch the Spotlight trailer, click on the photo.

Here’s why: Two ideas in that interview bridged the wide gap between investigative journalism and fiction writing. The first was the nitty-gritty aspect of journalism, which Robinson refers to as making the sausage: “how reporters disagree with one another, how we stumble around in the dark, how, sometimes, we find the most important things quite by accident.” (That sounds quite familiar.)

The second idea came from director and co-writer Tom McCarthy, who reminds us that the Spotlight reporters “…waited until they had it exactly right, and that’s something we rarely see nowadays, isn’t it? And I think, ultimately, it’s why when they did print this story, it was sort of beyond reproach. It was so definitive and so just powerful and complete.”

Today’s 24/7 news cycle rewards quick reporting over deep reporting, because the first appearance of a story will usually get the most views. What Spotlight reminds us is that it takes more time than we’d like to get it right, to establish all the details and connect all the dots so that it’s “definitive and powerful and complete.”

Fiction writers are also pressured to publish early and often, because nothing draws attention to the old books like a brand new one. Besides, we want to get our latest story out into the world ASAP so we can talk about it. (And like a favorite child, we definitely want to talk about it.)

Many novels I’ve read recently show the telltale signs of being published too quickly (even those with an agent and editor). And it’s easy to understand how that happens: with external and internal pressures aligned, it’s just too hard to keep slogging away until a story is the very best it can possibly be.

Another interview comment of McCarthy’s speaks to the doggedness that is a prerequisite for any writer who wants to polish and not just publish: “And it’s those reporters that have the passion to stick to it and stick with it and keep going back again and again and again. These are the people that break the big stories.” (Or, I would argue, write the “big” novels.)

Beyond doggedness, breaking a story as big as the child abuse scandal required the strong backing of a powerful institution like the Boston Globe. As McCarthy says, “It was Goliath vs. Goliath… They had the time to do this. They had the time to go back the next day and the next day and the next day. It speaks to a really strong, free press, a financially supported press that enables professional reporters to do their job.”

Now that this movie about journalism has been rewarded by the Oscar judges, I can only hope that will help keep investigative journalism a top priority—even as the internet continues to reward the quickest rather than the deepest.

One final note: although many of my favorite movies originated as books, I don’t think that process would’ve been good for Spotlight, because the most dramatic moments were built on subtle facial expressions and almost-off-camera body language. Maybe the right author could’ve captured that with internal dialogue and long-winded description—but maybe not. Better for this heartrending story to go straight from reality to the big screen.

As for my own next big story, I’ll be relying on a few of you—my first readers—to help me make what McCarthy calls “this sort of collective decision of when to go with a story.” Because the more excited an author is, the easier it is to press the magic publish button too soon.

April 28, 2016

The Secret Habits of Spring Trees

On this morning’s paddle, I figured out yet another reason why I like spring so much: each tree on the shoreline shows its own personality in deciding when to leaf out.

I’m sure there are more scientific reasons for the variations: location, tree type, etc. But I prefer to think of it as a “decision” each tree makes for him or herself. “I’m going to be an early spring leafer,” one might say, perhaps as a New Year’s resolution. Another might remember last year’s late April frost and stay “inside” for another week or two. (I’m sure there are several magnolias wishing they’d done just that this year.)

A few weeks from now, all but the most stubborn trees will be fully leafed out and making shade, changing the entire atmosphere for those of us living below them. So it’s only this week that I get to imagine each trunk of spreading branches as a separate entity, one that shows off its individuality with the only “decision” it controls.

People get to show off their individuality all year round—though as we ramp up our outside activity, spring decisions are often more obvious. I make a priority of getting out on the water regardless of season, so I’m reveling in the lengthening days and steady increase in water temperature. Meanwhile many friends and neighbors are still hiding inside, waiting for the warm winds of summer before venturing out. Shorts appear on some bodies much earlier than others—the result of a New Year’s resolution, or maybe it’s a simple scientific matter of location, type, etc. Either way, we’re not so far removed from our tree brothers and sisters after all.

This year, it’s not the mud-luscious and puddle-wonderfulness of spring I notice most. It’s the ever-changing visual feast. Every day is different; even morning to evening, what’s blooming and who’s leafing out can make significant progress. And unlike the fall, when one well-timed wind storm might strip all the leaves in a short blustery afternoon, this renewal phase will last for weeks.

The most stubborn trees won’t green out until mid-May, giving the first few Dutch Island circumnavigations a wintry bare-branched backdrop. Maybe it’s because they are surrounded by water… or maybe they are just following through on this year’s resolution, determined not to bud too early. Either way, the shoreline will look different on tomorrow’s paddle—just one more reason to appreciate this season of new growth, on whatever schedule works for each one of us.

April 21, 2016

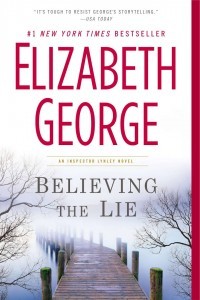

Book Review: Believing the Lie (if not the cover)

I’ve been a fan of Elizabeth George’s Inspector Lynley novels for a very long time, so on a recent library visit I was thrilled to find a new title lurking on the shelves. (For those of you planning to read any of these, don’t worry: there will be no spoilers here.) The fact that this one was more than two inches thick was an added bonus; even if I let myself devour it as fast as I wanted, I was still assured of several evenings of immersion in a new world.

In contrast to how I shop for books from unknown authors, I barely glanced at the cover photo before I checked out Believing the Lie. It was only once I finished the story (devoured, check) that I noticed the dock—and the more I looked at it, the less appropriate it seemed. I’ve never been to the English Lake District, where most of this story takes place, so it’s possible there’s a private pier in the area built with pressure-treated pilings and decked in well-maintained teak… but if so, it’s not mentioned in this story. My guess is that the photo was found on a US stock site, perhaps the result of a search on keywords like “fog”, “coast,” and “mystery.” Then again, thanks to its membership in a bestseller series, all this particular book cover really had to accomplish was to provide a legible background for a name and a phrase: “Elizabeth George” and “An Inspector Lynley Novel.”

In contrast to how I shop for books from unknown authors, I barely glanced at the cover photo before I checked out Believing the Lie. It was only once I finished the story (devoured, check) that I noticed the dock—and the more I looked at it, the less appropriate it seemed. I’ve never been to the English Lake District, where most of this story takes place, so it’s possible there’s a private pier in the area built with pressure-treated pilings and decked in well-maintained teak… but if so, it’s not mentioned in this story. My guess is that the photo was found on a US stock site, perhaps the result of a search on keywords like “fog”, “coast,” and “mystery.” Then again, thanks to its membership in a bestseller series, all this particular book cover really had to accomplish was to provide a legible background for a name and a phrase: “Elizabeth George” and “An Inspector Lynley Novel.”

In each of the 19 books in this series (and yes, I’ve devoured most of them), the two main characters (Scotland Yard Chief Inspector Thomas Lynley and his partner, Detective Sergeant Barbara Havers) age and grow while solving crimes that are variations on the murder and mayhem theme. Along the way, they delve into social issues at work and at home: rape, incest, homophobia, race relations… you name it. And that deep development (of both characters and their society) is how this book achieves its heft of 610 pages, without wasting too many words (more about that in a moment).

Once I opened the cover, I quickly became lost in the story’s unique twists and turns. I’m always impressed (both as writer and reader) with how George lets her characters’ strengths and weaknesses propel the story forward. “If you don’t understand that story is character and not just idea,” she explains in Write Away, One Novelist’s Approach to Fiction and the Writing Life, “you will not be able to breathe life into even the most intriguing flash of inspiration.”

Her books begin with a character in a situation. And that situation leads to an action, which triggers another action, like a carefully laid row of dominoes: “It knocks the next one over and so forth.” The really delicious part about George’s writing is that once we get to know her characters, their actions usually seem quite inevitable—though not quite predictable. And that gives her the luxury of waiting until later in the book to show us what actually happens next.

By writing in the third person, George takes us inside many different heads even while constantly (and seemingly effortlessly) moving the story along. She might let a story line dangle for a chapter or two, while she brings us up to date on another character’s progress… but trusting her to tie up any loose ends allows us to enjoy the suspense even more.

Another reasons she is able to let one story line go offline for a few chapters is that she ties seemingly unrelated characters together with small details. My favorite example in this latest book comes about halfway through, when she introduces a minor (offscreen) character. In the very next section, which is told from a totally different perspective, the name appears again. These small links build strong chains within the story, leading us to its surprising and yet inevitable climax. I will let you discover it for yourself, but be advised—it does not involve a dock of any sort.

As for that 610 page count: there were definitely more wasted words than I expected. George moved to a new publisher for this book, and it did seem a bit less finely polished than previous stories—especially in the sections told from Barbara Havers’ perspective. Instead of reducing a paragraph of internal dialogue down to one or two ideal sentences, the numerous originals were often allowed to remain. They made their point—just not quite as elegantly as I expected.

Fortunately, even George’s less polished prose is a pleasure. But those extra sentences (which some other readers have called “wasted filler”) remind us how important editors are; they have the power to make a book the best it can possibly be—if they are granted the luxury of time. With two bestselling names on the cover (the author’s, and the main character’s), the publishing decision-makers probably figured that good was good enough.

Last but not least, here’s one final side note about format: If this had been an ebook, the size and scope of the story would not have been as physically obvious. Then again, an electronic version would have spared me the distraction of tiny penciled handwritten notes in the margins, the residue of some very inconsiderate previous reader.

I’ve already purchased the next book in the series, and after I devour that one there’s another that just came out last fall. It’s a lot easier to read books than to write them, especially at this level of detail. So thanks to Elizabeth George for all of her hard work. I can only hope she keeps coming up with new Inspector Lynley stories for many, many years to come.

April 14, 2016

The Story That Didn’t Go Away

Back in February, I wrote a review of Big Magic. At the time, I agreed wholeheartedly with Elizabeth Gilbert: if the ideas that come to us don’t get prompt attention and grooming, they’ll fly off to someone else.

Today, I’m going to tell you a story that completely contradicts that theory.

The Idea

In January of 2012, a germ of an idea landed on my shoulder about a ferry captain who’d been put ashore. One of the first things I “discovered” about him was that he lived on an island—an imaginary island, because then I could bend the land to fit the story. I drew it out, dredged a harbor and built a ferry dock, wrote a few scenes and fleshed out a few characters. He’d been replaced by a female captain. And his girlfriend had dumped him when he lost his job…

Life Interferes

I was just gaining some momentum when other writing (of the immediately billable variety) claimed me. So I put the story aside, thinking I’d get back to it in a week or two—whenever I again had the brain space to continue.

Somehow, four years flew by… and then this past January, I finally worked up the nerve to peek into that island world. With Big Magic’s theory fresh in my mind, I was worried it would all be gone—that the words I’d written four years before would mean nothing now. Instead, I stepped off that creaky ferry right back onto that same wooden pier. Strolling up the big hill (the one that makes even the locals pause for breath halfway up), I greeted my character-friends again. Instead of flitting off to someone else, they had all patiently waited for me to return. What a relief.

What happens next

Three months later, life and work continue to interfere—but I’m making progress. Almost every day I make a new discovery: Oh, that’s what happens next! Or Wow, I didn’t know he was going to do that… which is hard to explain to anyone who thinks I’m driving the story bus. As I put it in September 2011, while working on what would eventually, after several false starts, lead me onto my imaginary ferry dock, “sometimes the only way to find out what happens next is to keep typing.” (Read more: Yes Dear: Listening to my Characters.)

Since I started writing again, I’ve been rather fanatical about not discussing the story in any detail—for fear it will flit away or turn into something else (maybe better, but maybe not). Instead I’ve been rushing to finish a rough draft, before I lose the magic of this island where I feel so much at home.

Standing back a bit, though, that fear seems rather silly. I ignored this same idea for four years, and it stuck around waiting for me to pay it some decent attention. Now that I’ve been working with it for a few months, it’s still here—more defined, different from the original, but still holding firm, just as a rocky island should. So maybe stories are less like butterflies and more like people, each with its own personality? If so, this one gets an A+ for persistence.

Thanks to Scrivener

Four years and three computers ago, I captured a mad collection of stuff into a single Scrivener file called, of course, “Island.” When I finally found the nerve to click open that file, it was all still there: Scenes. Ideas not yet fleshed out. Links. Two charts (large scale and small). And a whole slew of random research snippets about a fantastically wide range of unrelated topics.

Filing is not my strong suit, and if I’d had to piece together this story from a four year old folder of poorly named Word docs and Photoshop files, I’m sure my imaginary island would have flitted away in search of a more organized home. Instead, it did me the honor of sticking around until I had time to write it out.

So now I find myself happily disagreeing with Elizabeth Gilbert: not all un-groomed ideas leave us when we can’t give them immediate attention. Maybe this one understood that Scrivener would keep it safe, even while I was off learning the difference between a bowrider and a deck boat. Or maybe it knew I’d been thinking about it all along. Because even while I was writing about other things, whenever I looked out to sea I’d spot the faint hazy edges of my imaginary island.

And now if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go find out what happens next.

April 7, 2016

The Best Reading for Writing Well

On average, I probably read a book a week—almost exclusively fiction. And what I enjoy reading is directly linked to the current phase of my own writing. When not creating my own stories, I gobble up books that inspire me to write better with their careful word selection, surprisingly vivid imagery, and delicate phrasing.

When I am creating, I stick to less demanding reads, as far away from own topics as possible.

While fleshing out a new story, I can’t read anything too close to home until my imaginary world is completely established. The ideas that tap on our shoulder, provided by what many writers call a muse and Elizabeth Gilbert calls Big Magic, might just blend into the background like a camouflaged butterfly—and they’re all too easy to scare away. Similarly, a character hovering just at the edge of my imagination could be instantly contaminated, just by reading a choice detail about one who is too close (in lifestyle, or hairstyle, or any other style) to my own.

On the other hand, the edges of my imagination need a constant influx of stimulation, and one of the easiest ways to attract that is by reading. It’s way easier to read about an adventure than to actually go on one, and my writer’s brain can make the same hay out of each. Real adventures are actually harder to incorporate into fiction, because the details are way too vivid. They need the hazy film of perspective applied first, before they become pliable enough to be adapted into story.

So my ideal read while writing provides stimulus without distraction. At the same time, it also has to help my imagination shut down for the day, since almost all of my pleasure reading is just before I fall asleep. And that’s what leads me to the following basic principles about what books provide the best reading for writing well.

1. Go Light

Writing fiction is like building a new world from scratch. And world-building (whether it’s going well or not) is exhausting, which reduces the brain-power that’s available for reading at the end of the day. I often lack the energy to connect the unspoken dots, which is one of the true pleasures of literary reading. (I recently had to put down Lighthousekeeping for a few nights, until I had the brain power to really absorb its rich lyrical phrases.) Though I’m slightly embarrassed to admit it, I’ve learned to keep it light.

2. The Safe Zone: Chick Lit

When I’m writing well, my imagination needs help shutting off each night. That’s when my pleasure reading turns to chick lit, which usually has just enough character development to be engaging. And according to thriller author Mark Chisnell, even my own Olympic Love Story doesn’t even come close to ticking the chick lit box (read his review here), so there’s no concern about scaring away the Magic or contaminating a character of my own.

3. Don’t be afraid to dabble

I was taught to finish books, and it wasn’t until a few years after college that I realized I could put one down halfway through. With so many books and only an hour or so each day for reading, I now give myself permission to start a new book before I finish the previous one, especially if it’s something completely different.

Reading, of course, is much easier than writing, which is why it’s such a great escape. And somehow my brain manages to keep it all the adventures straight, especially if I’m reading an actual physical book with an associated cover, smell, and font. Like butterflies, we flit out of one world and into another, just by opening a different flyleaf. And isn’t that truly the Big Magic of books?

Photo courtesy PaulCroninStudios