Hieronymus Hawkes's Blog, page 6

April 13, 2025

Are We Nearing Peak AI?

#writingcommunity #booksky

#amwriting #writing Unfetterred Treacle

#amwriting #writing Unfetterred Treacle

I’m not too worried about the whole “technological singularity” thing, you know, the one where AI gets so smart it takes over everything and changes the world forever. That might be something to think about someday far off, but it’s not what’s been on my mind lately.

What I’ve been wondering is this: what if we’re actually closer to the high-water mark of AI than we think?

Not because the tech is running out of steam, but because the world it depends on is starting to show cracks.

We keep hearing about AI dominating the future, spreading everywhere, transforming everything. But what if those predictions are a little overblown? What if the real limit on AI isn’t how good our technological capability is, but whether the world can keep the lights on?

The Cracks in the Foundation

AI doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It runs on semiconductors, rare earths, high-bandwidth data networks, satellites, and server farms big enough to make a coal plant blush. And all of that? It depends on a global system that’s feeling more fragile by the day.

Between trade wars, tariffs, and the general messiness of international politics, we’re looking at some serious pressure on the systems that keep the tech world spinning. The current tariff landscape alone is enough to give economists indigestion, and there’s talk we might hit a global recession before the year’s out. That kind of squeeze makes it harder to keep building and powering the AI infrastructure we’ve come to expect.

The End of Calm Seas?

Since World War II, the U.S. Navy took on the job of keeping the sea lanes open. That was part of the Bretton Woods system, make trade safe, keep the world humming. It worked. For decades, American warships helped maintain peace on the water, and that meant reliable shipping routes for everything from coffee beans to cobalt.

But times are changing. The Navy’s aging. Budgets are tight. Priorities are shifting. And as Peter Zeihan has pointed out more than once, we might be looking at the slow sunset of the Pax Americana—the peaceful(ish) global order that made the modern global economy possible.

No Navy watching the seas? That means more piracy, more regional conflict, and more uncertainty in global shipping. And guess what needs stable shipping? Chips. Data centers. The entire AI ecosystem.

AI Is a Global Puzzle

Most folks think of AI as software, but the truth is, it’s hardware-heavy. You need silicon wafers from Taiwan, cobalt from the Congo, copper wiring, rare earth minerals, and massive data centers connected by undersea fiber. And to build just one advanced chip, you’re looking at supply chains that involve thousands of companies across dozens of countries.

Did you know? The semiconductor supply chain touches over 9,000 companies around the globe. That’s a lot of moving parts—and a lot of chances for something to go wrong.

We’ve already seen some warning signs: chip shortages, trade restrictions, nations starting to hoard key resources. And the tech world? It’s starting to split into rival camps—each with its own standards, rules, and systems.

If that trend continues, scaling up AI the way we have might become less feasible. Not impossible, but a lot harder, and a lot more expensive.

Are We Already Leveling Off?

Here’s the other thing: even the tech itself might be slowing down a bit. Some of the latest research is showing diminishing returns when it comes to training ever-bigger language models. Larger computers doesn’t always equal better results. You still need good data, smart design, and some human common sense.

And when you factor in rising hardware costs and geopolitical roadblocks, you start to wonder if we’re approaching a natural plateau.

Zeihan and others think we’re entering an age of deglobalization, where countries focus more on self-reliance, less on cross-border collaboration. That’s not exactly the best setup for building world-spanning AI systems, not to mention the ability to create the top end chips that AI relies on.

So, What Happens Next?

Don’t get me wrong, AI isn’t going away. It’s still going to shape the future. But we might see a shift from “bigger and faster” to “practical and more efficient.” Think less moonshot, more toolbox.

Instead of big, global AI, we might get lots of regional ones, each with its own quirks and rules. Some open source. Some locked down. Some focused on innovation, others built for control.

We don’t need AI to be godlike. We just need it to be useful, and maybe a little less dependent on a world order that’s looking shakier by the minute.

So yeah, I’m not worried about the rise of the machines. I’m more interested in whether the global conveyor belt that feeds them will keep running.

What do you think? Are we nearing the top of the AI curve, or just catching our breath?

April 4, 2025

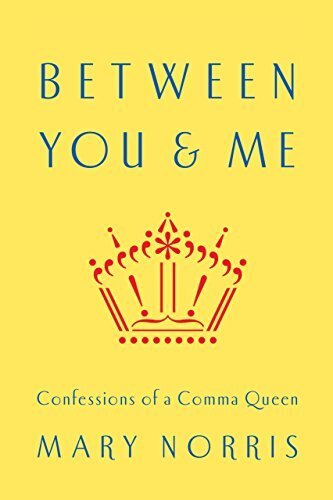

Book Review: Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen by Mary Norris

Grammar has never been this funny (or this profane).

#writingcommunity #booksky

#amwriting #writing Unfetterred Treacle

#amwriting #writing Unfetterred Treacle

Mary Norris spent more than three decades wrangling commas, hyphens, and the occasional authorial ego as a copy editor at The New Yorker. In Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, she blends memoir, grammar geekery, and a delightfully salty sense of humor into one thoroughly entertaining read. It was a 2016 Thurber Prize nominee for American Humor, and yes—it absolutely earned the nod.

The first half of the book is a behind-the-scenes peek at The New Yorker’s legendary editorial process—complete with turf wars over dictionaries, style debates, and the kind of writer-editor dynamics that will feel very familiar to anyone who’s ever worked with words. Norris recounts these stories with wit, warmth, and just enough sass to make you want to pull up a chair in the copy department and stay awhile.

Then the second half of the book takes a turn toward grammar itself—but not in the dry, diagram-your-sentences way. Think grammar with edge. Grammar with personality. Grammar that swears.

Yes, there’s a whole chapter about profanity. And it is glorious.

One of my favorite anecdotes involved an internal contest among staffers to sneak curse words into the magazine. (Spoiler: her mother would’ve approved—apparently, she had quite the mouth on her.) Norris somehow manages to make even comma placement feel a little dangerous, and that’s not a sentence I ever thought I’d write.

What surprised me most, though, was how reasonable she is. For someone who’s spent her life enforcing the rules of the language, she’s remarkably forgiving of their flexibility. Norris offers guidance, not commandments, and she ultimately puts the responsibility back on the writer to make the right call. Which means: no more blaming your editor for that misplaced em dash.

I bought this book thinking it would provide a lot of grammar instruction. It does give some very good nuggets, but I would not qualify this as a grammar how-to book.

But if you’re a grammar enthusiast, a New Yorker devotee, or just someone who enjoys the kind of memoir that comes with red pens and F bombs, Between You & Me is well worth your time. You might even learn a few things—like when to use a hyphen, or how to make a comma sexy. And if you’re lucky, you’ll come away cursing like a copy editor—with perfect punctuation.

I enjoyed this book and can happily recommend it.

April 1, 2025

5 Things I Hate About Writing Revisited

#writingcommunity #booksky

#amwriting #writing Unfettered Treacle

#amwriting #writing Unfettered Treacle

Written ten years ago. Still weirdly true.

I came across this list I wrote a decade ago, and it surprised me how much of it still feels relevant. The industry has changed. I’ve changed. But the core frustrations—the parts of writing that make you want to scream into a coffee cup—haven’t budged all that much.

Some things evolve. Others stay maddeningly the same.

Here’s what I wrote then—and honestly? I still stand by most of it.

1. Our schools don’t exactly set us up for success.

Let’s be honest, the way English is taught in most school systems doesn’t inspire a love for language. Grammar? Ugh. Studying writing felt more like punishment than discovery. I often wonder how many more people would enjoy writing if they hadn’t been made to hate it in high school.

When I decided to take writing seriously, I realized just how much I didn’t know. I had to fill in some major potholes in my skill set, and that realization eventually led me to pursue a Master’s degree in Writing Popular Fiction. I even took an undergraduate grammar class along the way—and, believe it or not, I actually enjoyed it. No, really.

2. Even when you know what you’re doing, writing well is hard.

Getting the words in the right order is one thing. Making them sing? That’s something else entirely.

I’ve participated in NaNoWriMo for the past decade and have seen people write hundreds of thousands of words in a single month. One person logged over 400,000. How? I honestly can’t imagine the prose is remotely good—but maybe that doesn’t matter. First drafts are supposed to be messy. The real magic comes in revision.

Still, writing is hard. I’m not complaining—just stating a fact.

3. Selling your work is harder than ever.

Yes, self-publishing is an option. But doing it well is a massive undertaking all on its own (and probably deserves its own blog post). The traditional publishing industry isn’t much easier.

If my time in the Air Force taught me anything, it’s this: change is constant. The same holds true in publishing. We’ve watched the industry consolidate under massive conglomerates. Many publishing houses are now owned by corporations that care more about quarterly profits than good storytelling.

Instead of championing original voices, they push books that resemble last season’s hits—playing it safe. They misread the digital market entirely, leaving Amazon to capitalize on the eBook wave. And here we are.

4. Writers don’t get treated well.

You’d think that the people who create the content—the authors—would be the most valued part of the equation. But more often than not, that’s not the case.

What the industry does value is your Intellectual Property. Your creativity. Your stories. But not necessarily you. As if your work just appears out of thin air.

In the military, I spent the last decade of my career in leadership roles. I believed in taking care of the people who worked for me. I encouraged them. I supported them. I genuinely think there’s room in the industry for a company to rise up and do the same for writers—one that treats authors like partners, not just content producers. Whether that will ever happen? I don’t know. But I hope so.

5. Routine is the real Boss Fight..

Let’s face it—writing regularly is a pain in the ass. And it’s that same ass that has to be in the chair, doing the work.

Every professional writer has a different rhythm. Some write every day. Some write for hours on end, seven days a week. Most of us can’t (or don’t want to) do that. Some people squeeze in writing on weekends. Others grab 15-minute bursts whenever they can.

But creating a consistent habit is a struggle for many—and I’m no exception.

My biggest challenge? Setting aside regular, protected time to write. Life doesn’t stop. The internet doesn’t shut off. Family responsibilities don’t pause.

And when I do finally get the time, the temptation to check email or scroll Instagram or binge a show is very real. Writing takes discipline. It takes intention. You have to make it a priority—and then fight to protect that time and actually use it.

___________________________________________________________

So, how’s your writing journey going?

Are there things you hate about writing? Or maybe things you didn’t expect to love?

Here’s the funny part, a lot of the things I hated about writing ten years ago? I still hate them. But I’ve also made peace with many of them. Some have even become oddly endearing—like the constant learning curve.

That’s the thing about writing, it changes. We change. The tools shift. The industry evolves. Trends come and go. But the core struggles? The doubt, the discipline, the desire to tell a good story? Those stay the same.

And in a strange way, there’s comfort in that.

It means we’re not alone. We’re just part of a long, chaotic, beautiful tradition of writers—grumbling about grammar, wrestling with structure, and fighting for every precious minute at the keyboard.

Still writing. Still figuring it out.

Still showing up.

5 Things I Hate About Writing Revisted

#writingcommunity #booksky

#amwriting #writing Unfettered Treacle

#amwriting #writing Unfettered Treacle

Written ten years ago. Still weirdly true.

I came across this list I wrote a decade ago, and it surprised me how much of it still feels relevant. The industry has changed. I’ve changed. But the core frustrations—the parts of writing that make you want to scream into a coffee cup—haven’t budged all that much.

Some things evolve. Others stay maddeningly the same.

Here’s what I wrote then—and honestly? I still stand by most of it.

1. Our schools don’t exactly set us up for success.

Let’s be honest, the way English is taught in most school systems doesn’t inspire a love for language. Grammar? Ugh. Studying writing felt more like punishment than discovery. I often wonder how many more people would enjoy writing if they hadn’t been made to hate it in high school.

When I decided to take writing seriously, I realized just how much I didn’t know. I had to fill in some major potholes in my skill set, and that realization eventually led me to pursue a Master’s degree in Writing Popular Fiction. I even took an undergraduate grammar class along the way—and, believe it or not, I actually enjoyed it. No, really.

2. Even when you know what you’re doing, writing well is hard.

Getting the words in the right order is one thing. Making them sing? That’s something else entirely.

I’ve participated in NaNoWriMo for the past decade and have seen people write hundreds of thousands of words in a single month. One person logged over 400,000. How? I honestly can’t imagine the prose is remotely good—but maybe that doesn’t matter. First drafts are supposed to be messy. The real magic comes in revision.

Still, writing is hard. I’m not complaining—just stating a fact.

3. Selling your work is harder than ever.

Yes, self-publishing is an option. But doing it well is a massive undertaking all on its own (and probably deserves its own blog post). The traditional publishing industry isn’t much easier.

If my time in the Air Force taught me anything, it’s this: change is constant. The same holds true in publishing. We’ve watched the industry consolidate under massive conglomerates. Many publishing houses are now owned by corporations that care more about quarterly profits than good storytelling.

Instead of championing original voices, they push books that resemble last season’s hits—playing it safe. They misread the digital market entirely, leaving Amazon to capitalize on the eBook wave. And here we are.

4. Writers don’t get treated well.

You’d think that the people who create the content—the authors—would be the most valued part of the equation. But more often than not, that’s not the case.

What the industry does value is your Intellectual Property. Your creativity. Your stories. But not necessarily you. As if your work just appears out of thin air.

In the military, I spent the last decade of my career in leadership roles. I believed in taking care of the people who worked for me. I encouraged them. I supported them. I genuinely think there’s room in the industry for a company to rise up and do the same for writers—one that treats authors like partners, not just content producers. Whether that will ever happen? I don’t know. But I hope so.

5. Routine is the real Boss Fight..

Let’s face it—writing regularly is a pain in the ass. And it’s that same ass that has to be in the chair, doing the work.

Every professional writer has a different rhythm. Some write every day. Some write for hours on end, seven days a week. Most of us can’t (or don’t want to) do that. Some people squeeze in writing on weekends. Others grab 15-minute bursts whenever they can.

But creating a consistent habit is a struggle for many—and I’m no exception.

My biggest challenge? Setting aside regular, protected time to write. Life doesn’t stop. The internet doesn’t shut off. Family responsibilities don’t pause.

And when I do finally get the time, the temptation to check email or scroll Instagram or binge a show is very real. Writing takes discipline. It takes intention. You have to make it a priority—and then fight to protect that time and actually use it.

___________________________________________________________

So, how’s your writing journey going?

Are there things you hate about writing? Or maybe things you didn’t expect to love?

Here’s the funny part, a lot of the things I hated about writing ten years ago? I still hate them. But I’ve also made peace with many of them. Some have even become oddly endearing—like the constant learning curve.

That’s the thing about writing, it changes. We change. The tools shift. The industry evolves. Trends come and go. But the core struggles? The doubt, the discipline, the desire to tell a good story? Those stay the same.

And in a strange way, there’s comfort in that.

It means we’re not alone. We’re just part of a long, chaotic, beautiful tradition of writers—grumbling about grammar, wrestling with structure, and fighting for every precious minute at the keyboard.

Still writing. Still figuring it out.

Still showing up.

March 28, 2025

“Get in There!” — Learning to Write in Deep POV

#writingcommunity #booksky

#amwriting #writing

#amwriting #writing

I was trying to explain what it felt like to write in Deep POV the other day and this image popped into my head that was a perfect analogy. Flash back to early 1987. I’m sitting in the left seat of the tandem T-37 jet trainer. It was my first formation flight, and I was on the wing. That meant the pilots in the other T-37 were flying lead and it was my job to stay on the tip of their wing. Literally.

The T-37 was first delivered to the Air Force in 1959 and had the highest G onset rate of any aircraft in the inventory at the time and was used for the first phase of Undergraduate Pilot Training, focusing on aerobatics and spin recovery. It was a blast to fly, despite being very basic.

Later, I flew this jet again in the ACE program. Accelerated Copilot Enrichment—for B-52 and KC-135 copilots to stay sharp. Mostly, I used this to fly to Muncy, Indiana to eat at Foxfire, Jim Davis’s restaurant (Yes, Garfield Jim Davis.) You could park your jet right in front.

But back to the story.

There I was…

(That’s how a lot of pilot stories start, usually with hands replacing the aircraft. Some referred to this as “shooting your wristwatch.”)

But there I was, sitting in the left seat, but not in control of the jet. My instructor was flying and had us in a loose trail position, behind lead, and he was about to show me how to move into position. Lead was flying straight and level. The IP accelerated, moved up, slid in—closer, closer—until we were 3 feet off of their wing.

Three. Feet.

Going a little over 200 mph.

He held us there, calm and steady, then asked, “You ready to take it?”

I said yes, nervously, and took the stick. “I have the aircraft.”

Within seconds our aircraft was like a ribbon in the wind, moving up and down and slowly but steadily away from the other aircraft.

I don’t know how many students my instructor had before me, but he was quite impatient. “Get back in there!” he barked.

20 feet away felt much better. I could stabilize.

Fifteen feet? Still okay.

But three feet? That was a whole different level.

And honestly, that’s exactly how it felt when I was writing close point of view before I understood Deep POV.

I tried to edge closer, to get tighter into the character’s skin, but I kept slipping out. I’d float into safer distance, into that 15 or 20 foot range of perspective, where it felt more comfortable, less vulnerable.

My instructor took the jet from me and quickly repositioned us at 3 feet. “Ok, take the jet.”

Once again, I maintained position for a microsecond and then we waffled out to 10 or 15 feet.

“Get in there,” he shouted again.

Rinse, repeat.

If only Deep POV was that easy. Just have someone else get me in there and help me stay there. But the first writing efforts mirrored those training flights, lots of drifting out, lots of pulling back. On each subsequent pass I could almost hear my IP yelling at me.

“Get in there!”

Eventually, I figured out how to stay at 3 feet. It just takes calmness and steady attention. And lots of practice.

(For the record: Close trail in the T-38—way faster than the T-37—was maybe the most fun thing I ever did with my clothes on.)

My editor had me do some Deep POV exercises, with my clothes on, and after half a dozen tries it started to click. I’m still learning, still refining. But I now understand what it feels like to really be in there, inside the character’s head, experiencing the world from three feet instead of twenty.

It’s not magic. It’s a skill.

And once you’ve got it, it’s yours for life.

March 26, 2025

So…What Do You Write (Cue Existential Crisis)

#writingcommunity #booksky

#amwriting #writing

#amwriting #writing

You’re at an event, surrounded by writers or well-read folks. Maybe it’s a book signing, a panel, a casual gathering. You’re feeling pretty good about being part of this community, until someone asks the question:

“Do you have a book out?”

That’s the common question.

You smile. “Yes, I have one published book.”

And then they hit with the follow-up…the one you dread:

“What genre do you write?”

That’s when it happens. The inner cringe. The throat-tightening pause.

I quickly answer, “Science fiction.”

Cue the wave of embarrassment.

Now, if I am at a convention filled with other SF & F people? No problem. I light up. I belong. But out in the wider world—where people aren’t gathered because of their shared love of warp drives, galactic empires, or fairies and dragons—it’s different. That’s when it creeps in. That all too familiar feeling.

I’ve loved science fiction since I was 11 years old, when Star Wars hit the big screen and everything changed. I devoured fanzines, watched Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Battlestar Galactica, and Alien. Awe inspiring stuff to a preteen boy with a head full of stars. I’ve been a lifelong fan of science fiction and fantasy ever since. I have great respect for the genre. I even got my MFA from a program that focused on Popular Fiction.

So why the guilt? Why the embarrassment?

We all kind of know why.

Despite billion-dollar movies and cultural phenomenons like Harry Potter, genre fiction still doesn’t get the respect it deserves from certain corners of the literary world. It’s still considered “lesser” by some—especially the crowd that leans literary. They prefer their fiction grounded, quiet, introspective. Realistic. And if you show up talking about space vampires, they assume you’re not a “serious writer.”

Never mind you’re writing about grief, or identity, or humanity, or power, or love. If your characters are on a spaceship instead of in a Brooklyn brownstone, well…good luck getting invited to the serious table.

My first book was a techno-thriller—grounded in near future science, with just enough speculative edge to keep it interesting. It wasn’t quite as embarrassing. But now? Now I am writing a space opera with a 700-year-old vampire as the protagonist. And every time I say it out loud, I can feel it, the voice in my head whispering, They’re judging you.

This isn’t real literature.

You’re not a real writer.

This is silly, pulpy genre stuff.

But here’s the truth. My book deals with identity, memory, redemption, power and betrayal. It’s about what it means to be human—and to lose that humanity. It’s not a comedy, although hopefully there is some humor in it. And I am rewriting it again, digging deeper, trying to get it right.

So where does this shame come from?

One word: (ok, it’s really 2 words) Imposter syndrome, raising its ugly head once again.

I heard Harlan Coben this morning talking about his 37th novel, and imposter syndrome. He said he wakes every morning afraid he’s not a real writer. Maybe that was hyperbole, but maybe not.

Maybe we never really get over it.

I do love science fiction. I love the imagination, the freedom, the challenge of exploring real human issues through a speculative lens. I love building worlds that reflect our own in strange, distorted, sometimes illuminating ways.

And I want to be proud of what I’m doing. Even though, some days, I’m not.

But it won’t stop me.

I’ll keep writing, because that’s what real writers do.

March 24, 2025

The Birth of a Story

I’d made the decision to write a novel.

I had no idea where to start. I hadn’t written anything for ten years, and nothing approaching even novelette length, let alone a novel length story. So, I came to the first conundrum that most new writers come to. What do I write about?

“Where do you get ideas?” is a very common question for writers. I did have other hobbies besides playing games. I liked to read. Mostly science fiction, but other things as well, like urban fantasy or historical drama. I also enjoyed poker. I learned to play back when I was a lieutenant in the Air Force, and it stayed with me.

I was noodling with ideas, and I kept coming back to having a story with a poker game, but the kicker was it had to be at a space station. So, I had to figure out a reason the players were on a space station. I came up with the idea that they were sitting on standby as part of a scout unit. But why did they need to be on alert? I landed on stargate protection. They were there to keep an eye on things, protect from pirates and other bad actors. Stargates have been done quite a bit. Eve Online came out in 2003, and I had played that game. It’s truly visually stunning. Not to mention the tv series Stargate. So, the idea for stargates was pretty well established.

So that was one scene in the story. Something to build around.Subscribed

I needed characters to populate the story. Somebody had to own the stargates or operate them. I figured my protagonist would be playing poker and was a member of the scouts, but I needed a bad guy. Well, I had gathered a lot of materials for the game Vampire: The Masquerade, and even though I never actually played it, I did read a lot of the companion books associated with the game. It was exceptionally well done. Vampires had been popular on and off for decades. I started working on this book in February or March of 2008, later that year, Twilight would be published, which only confirmed that using a vampire was a good choice at the time.

Combining two things I really love, space opera and vampires, now that sounded like fun.I thought the bad guy might be a vampire, and he owned the stargates. I made them a result of a meteor strike that carried an alien phage. Not traditional vampires, something new, or newish. Somehow living a long time had allowed my vampire to invest well and eventually his company invented stargate travel. Once I hit on this idea, I started fleshing out his character and started to really like him. I liked him so much I flipped the story around and made him the protagonist and started noodling with plot ideas, until I came up with something that made sense. By April 20th, 2008, I was writing the first chapter of a poorly designed story. Hey, it was my first story, of course it was bad.

And it wasn’t really designed. I really had no idea what I was doing, but I was writing, seat of the pants, letting the characters take me where they wanted to go. I was having fun, and I had plenty of confidence, but it wasn’t until I showed these first bits to some friends of mine that I realized how bad it was.

After a few attempts I started over, renamed the story and changed from first person point of view to third person point of view, and I renamed most of the characters and refined the plot a little and tried again. By this point I had added in a second point of view character, a fiery female pilot that works for the enemy company. Like most new writers I rewrote the beginning a thousand times. But then I settled down and moved the ball forward. Once I got about three-quarters of where I thought the story was going, I sat down and outlined to the ending. I distinctly remember writing the last few days on my iPad with a Bluetooth keyboard. As I closed in on the end, I wrote ten thousand words over two days while sitting alert, waiting to fly support missions for Operation Odyssey Dawn in 2011.

I got a little more feedback and realized that I needed a little more education. I didn’t even know what a speech tag was. I started looking for low residence MFA programs. I didn’t do it to get credibility in the community or to get bona fides to teach. I did it because I didn’t have the tools to write. I found the MFA in Writing Popular Fiction program at Seton Hill University. I loved every second of it. At that first residency I found my tribe. It was such a rush to be around people that loved to write. It was a new experience for me at the time. It made a huge difference in my writing. But that was only the first step to improving.

That’s how I started writing. That novel went into the trunk for a few years. I still have those very first pages. Perhaps at some point I will share them.

A few years back I pulled it out and rewrote it again. I had it edited and wrote the sequel. But now I am going back, after getting more insight from my new editor, to fix some major plot problems and to try to master Deep Point of View. I have hopes of creating an even better story than the original. Some days I question if I have any idea what I am doing, that perhaps I wasn’t meant to be a writer. Other days it’s okay. You read a piece that you wrote and it’s pretty good. It validates you.

Imposter syndrome is real.

The only way to fail at this, or anything worth pursuing, is to stop trying.

March 18, 2025

Saving My Progress: How I Traded XP for Word Count

How I became a writer

Until the age of forty-four I spent most of my free time playing games. Mostly video games.

I’d been obsessed with computers ever since the TRS-80 came out in 1977. A friend of mine had one shortly after they were released, and eventually I found a used one for myself and took it to college. It ran on level I Basic. It used cassettes to run programs, and it had some interesting text only games.

My college roommate bought an Apple IIe, a major upgrade. We played some early computer games on that with actual graphics, even though they were crude by today’s standards. I remember playing a lot of Lode Runner, came ut in 1983 and there was no save game function. We would race back after class to get on the computer and play until we died, then it was someone else’s turn. That got rough when we got into the hundreds. When someone reached a new level they would call out and we would all gather around and watch until it was our turn to try. I bought SunDog: Frozen Legacy, published in March of 1984 and it was hailed as the most impressive and absorbing game to come out. It set a new standard for complexity and ease of play, setting the stage for more to come.

A few years later, after I finished flight school and having gone without a computer for more than a year, I bought a Tandy TX1000 in 1988. It had the first hard drive for a personal computer, a whopping 20 megabytes. I had a 1200 baud modem, baud is bits per second, and a dot matrix printer to go along with it and it cost me more than two thousand dollars back then. The games got better, and the computers got faster and more powerful.

In the mid 90s, I was fairly savvy at building my own computer rig and tried to keep up with the changes in language and the new Windows program. I gave up around 1999. I was too busy with three kids at that point and working a lot, and the programming was changing so fast.

But there was a game on America Online, by this time we had doubled our speed to 2400 baud dial up, that was the first multi-player game. It maxxed out at 100 players. Neverwinter Nights was a version of the AD&D gold box PC games. It was 2D, the graphics were very simple, and the gameplay was limited, but we supplemented the gameplay with writing about our characters on a forum for our player guild. That was my first foray into writing creatively.

From there I played Meridian 59, Ultima Online, Everquest 1 and 2 and World of Warcraft. There were others of course; but those were the Massive Multiplayer Online Role-playing Games that took up the bulk of my time.

I was an instructor pilot in the Air Force and Air Force Reserves, and I basically spent my time playing video games when I wasn’t working or doing something with my wife or kids. The kids grew up on my knee, watching me play games. My eldest son got a degree in game design, and both my boys are following in my footsteps, as they spend the majority of their free time playing video games, much to my chagrin.

All of that to say I reached my mid-forties and felt like I had nothing to show for my efforts. Did I have fun playing all those games? Yes, but ultimately playing games no longer satisfied me. I wanted to have something tangible for the time I spent. I wanted something more.

I had never been a car guy. I didn’t know how to play any instruments. I thought about woodworking, my stepdad has an incredible woodshop, with a lathe and a planer, a table saw, and a jigsaw, all the tools needed to make anything. But I had very few useful woodworking tools and no space for a shop.

I made the pivot to writing. I had no idea how to start or what to write but I was going to do it. I was going to write a novel.

March 14, 2025

Failure is the best teacher – learning to take critique

Criticism may not be agreeable, but it is necessary. It fulfills the same function as pain in the human body. It calls attention to an unhealthy state of things.

-Winston Churchill

When you first start out as a writer you become a dichotomy of wants. You want people to love what you are doing, but you also want to keep it to yourself because, why would you want to expose yourself that way?

When you finally reach a place where you are ready to have someone else look at your writing, you secretly hope that there will be nothing that needs improvement. They will fall in love with your words and prepare to throw a parade when you finish your masterpiece.

In reality, I imagine there are extraordinarily few, if any, writers that can achieve that out of the gate. Most of us have some learning to do and may not even have a clue that we do. The first step is letting it go. Because we are so close to the writing we will often be blind to the problems it has.

Those first critiques are hard to take. Let’s not kid ourselves, they’re all hard to take on some level. But, at first, I think we are all a little resistant to want to hear anything negative or have the desire to change the perfect words we’ve written. We want to argue with whoever the critiquer is about why they are wrong.

I’ve seen it in many critique groups when a new person joins the circle. They aren’t ready to learn anything yet. Their dreams haven’t been trampled enough yet.

I kid, but it’s kind of true. We all go through a period of writing horribly and not being able to see what is wrong. That is the essence of why we get critiqued in the first place. Deep down we know, in those parts of ourselves that we rarely acknowledge, that something is off.

I’m not sure why it takes so long to start listening to that voice, but I can guarantee you, that voice is always right. We will see something weak in a passage we’ve written, but in that moment can’t see how to improve it, so we let it go to see if the reader will notice.

They always notice. Always.

We need to learn to trust that voice and save everyone from enduring your experiment and just cut it. This is also a learned skill.

There are multiple avenues to get critiques. A quick google search turned this up:

49 Places to Find a Critique Circle to Improve Your Writing

When I was desperate to find a crit group 15 years ago, I found a great resource online, since I had nobody physically close enough to meet in person. Critters Workshop. You earn credit by critiquing others. There a lot more these days of you do a simple search.

You might have a group of writer friends that you can share with in person. There are people that might serve as Alpha or Beta readers for your work.

Critiques are going to vary greatly. We did small group critiques for my MFA program, and even there you get a wide variety of responses.

There are several schools of thought on how a critique group should work. We used the Modified Milford method of critiquing, which meant you as the author had to sit quietly while everyone in the group got a chance to critique you, live and in front of everyone else. At the end the author got to ask questions. We received written copies of the crits afterward as well, which I found useful and often more valuable than the verbal critique.

Milford has been the standard technique for a long time, but new methods are popping up now that are less oppressive and more collaborative. On the Clarion West website they breakdown the workshop methods very nicely.

You are going to find that crit styles vary as much as people do. Some are performative, some are just extremely nitpicky. Some are on the mark and useful. You need to consider the background and experience level of the critiquer as well. Some may be published authors, some may be experienced writers who have done the critique sessions many times, and some may be new to the process.

Ideally the feedback should be constructive. Kindness goes a long way.

So, what do you do with the criticism?

Approach the critique with an open mind, but with a dollop of skepticism. They are not going to have equal value to you. Some will be completely worthless. Some will be fantastic. Some people may offer you a solution to what they perceive as the problem with a particular passage. This is generally frowned upon and usually won’t fit with your vision anyway. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem with what they are pointing to.

Here’s the thing. All critiques are just other people’s opinions. Keep that in mind. You don’t have to do anything with them. Your work belongs to you, and you have complete freedom to do what you like.

However, if multiple people are pointing to the same part of your story, then there is probably something there that needs to be fixed. What that will look like is up to you.

Keep in mind also that you volunteered for the critique. I don’t think people are signing up just to be mean to other writers; usually they have good motives. Some people are just better at it than others.

Workshops and critique groups are just the beginning of this torturous journey.

Next level is when you send it to a professional editor or an agent. The editor will definitely give you a lot of feedback, you paid them after all. The agent may or may not. If it’s not for them, they will likely say that it wasn’t a good fit. Or you might hear nothing. If it is for them, they may try to edit it. If it is bought by a publisher, they will have a professional editor go over it and then you will have a choice, make the changes they want or fight for what you want. You may lose the deal if you choose poorly.

My experience with editors has been positive. The ones I have used are very detail oriented or have great vision and they can see things you can’t. Again, the ball is back in your court to make changes or not. Somewhere along the way you will learn to let go of your ego and learn from the critiques you get. That is the entire point after all.

At the end of the day, learning to take critique is about growth. It’s about shifting from defensiveness to curiosity, from resistance to resilience. I’d like to think that the best writers—no matter how experienced—never stop learning. Each critique, whether from a peer, an editor, or a reader, is another opportunity to sharpen your craft, to see your work through fresh eyes, and to build a story that truly resonates.

Yes, it can be tough. Yes, it can bruise the ego. Writing isn’t about proving you’re already great, it’s about improving your skill with every draft. But the real skill isn’t just in writing, it’s in rewriting, refining, and embracing the process. The sooner you let go of perfection and lean into feedback, the stronger your work will become.

So, take what helps, discard what doesn’t, and keep writing. The only failure is refusing to learn.

March 12, 2025

Deep POV – More feels, less filters

This week I had an epiphany. I got something from my new editor that I wasn’t expecting. I think we all hope our readers are going to read our work and be awed by how amazing it is. We want to hear from our editor that there is nothing wrong and it’s ready for the world. That rarely happens, if ever. But if we are being honest that is not why we hired the editor. We want to hear the hard truth.

It’s appalling how hard it is to educate yourself in the craft of writing beyond the basics. Did you know in Europe you can get a PhD in Writing? Not in the United States. I may be oversimplifying this, but teachers will show you a few tricks of the craft and give a some examples and set you on your way. They tell you to write a million words and it will all become clear.

Thanks for reading Unfettered Treacle! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribed

I’m being a little facetious, but it’s not far from the truth.

I remember getting the first critique back from my first MFA mentor. He told me I needed to go deeper. “Read Coma,” he said. He actually meant was: “Read the opening chapter. See what it means to have a deeper point of view.”

But that wasn’t what I heard (because that wasn’t what he said.) I read the entire novel in a couple of days. I didn’t understand what he really meant, and I learned nothing from that exercise. I understood at a very rudimentary level that he wanted me to get in closer to the main character’s perspective.

My next mentor, who was amazing, cut filter words from my text. Words like, thought, felt, saw, heard. I understood that. I learned to use body cues to show emotion. I learned a lot of other things as well that had nothing to do with point of view.

I wrote a lot of words. My writing incrementally improved. But my understanding of Deep POV did not.

Then a friend of mine who went through the same MFA program, but had better mentors (we did share one,) decided to try out the editor gig. He has a pedigree. He taught writing at the collegiate level for several years and had gleaned a lot more about the process than I had. Writing was still a hobby for me. It was a job for him.

If you want to get good at something there is no better way than teaching. It worked the same for me teaching systems for the KC-135.

I put my manuscript in his hands to read, simply as background for the second book in the series, but he put on his editing hat as he was reading and next thing you know I got a 122 page document on the problems with my story.

My next blog is going to be about taking critique…

Jacob Baugher knows the keys to Deep POV. He talked about genre and plot, and yes, those need addressing, but the big lightbulb moment for me was when he started talking about Deep POV. I ordered a few more instructional books based on his recommendations.

It just so happened that same day I got an email from writersinthestormblog.com, talking about, you guessed it, Deep POV.

Serendipity.

The writer of that piece is Lisa Hall-Wilson and she talks almost exclusively about Deep POV on her blog. She talked about how hard it was to find ways to educate yourself beyond the basics and spent years learning Deep POV. She has written a book about it, which I now have, and teaches a master class on how to do it.

For at least a decade, Deep POV was one of the techniques I’d aspired to learn. Although I didn’t know that’s what people were calling it.

My favorite books are those that make you forget you are reading. It feels like you are experiencing the story along with the main character. Matthew Woodring Stover is one of the novelists I can point to that has Deep POV down. He has written eleven novels and several screenplays, including my favorite Star Wars book, Shatterpoint. But even though I could point to stories that I love, I still wasn’t recognizing what they were doing that I wasn’t.

Not until Jacob talked about it in the pages he sent me. The light bulb went on.

I have started on Lisa Hall-Wilson’s book, Method Acting for Writers: Learn Deep Point of View Using Emotional Layers.

She claims that the skill isn’t hard to learn, but it is not an intuitive way of thinking. My hope is that by the end of my rewrite it will become more intuitive.

So, what is Deep POV exactly?

It’s an immersive technique that eliminates any distance between the reader and the character. It’s writing in a way that puts you in the head of the point of view character (POVC) and keeps you there.

Which means cutting out telling about what is going on or explaining how the character feels about something.

You need to show it in a visceral way.

This is “Show, don’t tell” on steroids.You have to dig into the underlying emotional state of the POVC and get to the root of WHY they feel that way. It will require you as the writer to deeply understand your POVC.

You will need to remove the author’s voice as much as possible, meaning no narrator other than the POVC. Everything must come from the character’s perceptions and worldview. The fundamental key is understanding what is motivating the character at a deep-seated level, rooted in the events that have formed the character’s world view, for better or worse. The reactions in a given scene may be the result of a multiplicity of emotions and understanding that is key to being able to write Deep POV well.

Now, not every story needs to be in Deep POV. And not even an entire book necessarily, but I do think it will take your writing to the next level if you can master it. I hope to.

Special thanks to Jacob Baugher for setting me on this path. I hope together we can achieve something elevated. I cannot say enough great things about his approach. I highly recommend him if you are looking for an editor.

#WritingCommunity