Iris Dorbian's Blog, page 6

October 28, 2015

Thinking More About the late Anita Sarko, Early ’80s Downtown NY Club DJ

Call her whatever you want–the doyenne of early 1980s New York City club deejays or the grande dame of the downtown NYC New Wave club scene, but Anita Sarko, who took her life last week, was in her heyday–a supernova in a galaxy of wannabes. Unlike so many others that flooded the clubs (of which I was one), Sarko was unequivocally and singularly the real thing.

She was older than most of us who would frequent the clubs and in a strange way, at least to me, that wasn’t a strike against her–but rather something that lent her additional gravitas and credibility.

To me, she was coolness incarnate, a model of what I wanted so desperately to be back then but could never attain due to my innate shyness and profound lack of sophistication. Not that I didn’t try but my efforts always fell consistently short.

But Sarko didn’t have to try so hard to be cool. She just was.

During the time (early to mid-1980s) when I fed on the New York City club scene the way a junkie feeds on heroin or a vampire on blood, Sarko was a ubiquitous presence.

Her lair was the deejay booth and she reigned supreme in all the hot and happening clubs of the day: Danceteria, Area, the Mudd Club and later the Palladium.

My favorite club was Danceteria and it was there where I would always see Sarko in the booth spinning the discs.

She was instantly noticeable to me and always intimidatingly cool with her short asymmetrically cut, perfectly spiked blonde do, her exceedingly hip wardrobe and jaded brashness that came as effortless to her as my rampant suburban unsophistication.

As I related on my FB page when I first heard of Sarko’s passing, I remember the first time I approached her with a music request. It was to play The Smiths. She told me very matter-of-factly that she hated the Smiths. HA-HA! So that was out!

She wasn’t mean but very direct and brash in her manner as if she had no time to waste on inconsequential banter or anything that could detract her from practicing her art–which was entertaining the unwashed rank and file with her delicious and ingenious assortment of music mixes.

Unlike the regular rotation of young male deejays who were always too happy to comply with my requests (probably because I was a young female), Sarko could project crustiness to the terminally thin-skinned. Maybe because I’ve always been ruled by my contrary impulses, but I didn’t let her initial rejection of my Smiths’ request to deter me from asking her for other requests. From then on, she was affable as if I had passed a test.

I remember asking her if she could play a demo tape of a dance song I had composed with another musician. The lyrics I penned were forgettable and silly but the rhythm was catchy. To my delight and surprise, Sarko did play it, which was great. Although that tune never went anywhere (and in hindsight perhaps that was for the best), I remember gushing to my mother later on that Anita Sarko, the great cool club deejay Anita Sarko, had played my song in Danceteria! That seemed like the highest validation to me. I was in euphoria for weeks afterwards.

Then when I veered away from music and began focusing more of my attention on acting and auditioning, I stopped going to the clubs. But I never forgot how important that world was to me and I never forgot Sarko. To me she was not just synonymous with that scene but its most iconic and glorious personification.

Two years ago I thought about her and googled to see what she was doing. I found her Twitter handle and instantly followed her. Unfortunately, her tweets were minimal at best.

I remember reading in one of the articles that I found after googling how she wanted to write a memoir, which made me think: “Oooh. What a great idea! I would definitely buy that!” Sadly, that memoir will never come to pass now.

The more I read about her recent circumstances that preceded her suicide—-her valiant fight against cancer, which she had presumably triumphed over (and had written about) and her growing despair at being shunted aside in in favor of the young’uns–the sadder it made me.

She should have taken Michael Musto’s advice and offered her services as an iconic 1980s’ club deejay to gay weddings or special themed functions. Only she didn’t, as he said.

Did she expect the party to return? Was she stuck in a time warp? Or did she feel like a bygone relic of an era long past? As I never knew her personally, I can’t answer with any glib explanation. It’s all a blur–just like the 1980s seems to me right now in late 2015.

A friend of mine, who was also a frequent club patron during the time that Sarko reigned supreme, suggested to me that her depression could have been the tragic aftermath of her cancer treatments. Certainly, that didn’t help her malaise.

When I read that she died by suicide (I thought in the initial reports her cancer had returned), I was hoping she did it through peaceful means not harshly ala Robin Williams or L’Wren Scott. But according to one article I read, a rope was found around her neck. Horrible.

I don’t know what else to say. I hate to invoke that tired and trite cliche of how an era that was so dear to me has died symbolically with Sarko’s death but it has.

Nothing more is left to be said.

RIP Anita Sarko

October 25, 2015

Why I Left Theater – New Personal Essay

Why I Left Theater – New Personal Essay

Over the years, people have always asked me why I stopped acting. Invariably, I give them stock replies along the lines of “I was tired of being broke,” “I didn’t like the business” or “I wanted to be a journalist.” They’re all true. But the real catalyst that got me to seriously make the switch was an involvement I had with a project that started off so promising at the onset that when it did fall apart, it left me with such a sour distaste for the business and what it does to people (who could have been decent human beings otherwise) that I felt I had no other recourse but to get out.

It’s not an experience I like to discuss or recount. In fact, I rarely discuss the details because still as I recall the project that was my acting Waterloo over twenty years later it lingers as a scar whose origins of affliction I’d rather not broach–ever. And being that I haven’t been involved in theater–as an actor that is–for so long, there was never any solid reason I should regale anyone with that awful story that I had preferred to keep hidden away in the mental attic storing similar bad memories best forgotten.

But I’ve decided to reveal this one. And it’s not pretty. In fact, it’s still deeply upsetting to me. And you’ll realize why when I tell you this story.

In the early 1990s, I answered an ad in Backstage (where I had worked part-time as an editorial assistant for a year during that period). Stanley Brechner, the artistic director of the now defunct American Jewish Theater, located in the heart of New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood, was seeking actors who were children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors for a workshop he was putting together. There was no fee for the workshop yet there existed an abiding layer of hope that the material the actors would come up with under Brechner’s tutelage might develop into an actual play. And, as any amateur theater aficionado will tell you, this is exactly how “A Chorus Line” got started.

Well, I sent in my photo and resume. (This was the pre-Internet age so we all used mailers back then). Brechner called me up to meet with him. I don’t remember if I did a monologue–I might have. He asked me several questions and then asked me if I would be interested in joining the workshop. Of course! Absolutely! I mean, AJT was an off-Broadway house and I had done so many nonpaid off-off Broadway showcases, I jumped at the chance. Although the possibility of doing an actual run was remote, there was still hope that it could come to fruition. And, actors do live on a diet of hope.

I also saw the workshop as a chance for me to FINALLY unburden myself of the feelings I had about how my father’s post-traumatic stress disorder as a Holocaust survivor had affected me while I was growing up and how it still affected me then as an adult woman. I loved my father–he was a wonderful, kind-hearted man, a consummate gentleman. But the amalgam of phobias and idiosyncratic behavior, punctuated by alternating bouts of insomnia and nightmares, all of which obviously emanated from his concentration camp ordeal fifty years earlier when he was still very much a child, was unsettling.

The workshop began in early January 1993 and ran until May. We met every Saturday at AJT. There we would go through the paces of improvisations suggested by Brechner and see what would evolve from there.

We also shared with each other a lot of cathartic bloodletting that felt more like group therapy versus the burgeoning theater project we were trying to be. Belying my original motivation, often I had no idea if this was going to move beyond a workshop level but I didn’t care. It was so good being part of this communion of sharing, the healing, nurturing presence of other kindred souls who “just knew.”

To help us develop material, Brechner hired a young aspiring playwright who would observe what we worked on during our Saturday sessions and then use that material to create a play.

We eventually came up with enough material for a full-length presentation. There were monologues, interspersed with scenes and songs.

I sang a dark Holocaust song that my father taught me. I don’t remember the words but I remember it was in Yiddish and many found it very haunting and ominous.

I was also in two scenes. In one scene, I played a daughter who was completely insensitive to the plight of her traumatized survivor father. Her callousness causes her to have an angry confrontation with her mother. I remember I had to cry in that scene, which for a lot of actors can be very difficult. But for me, it surprisingly wasn’t.

That was the only scene in the presentation that was not written by the playwright. It was written by an actress in the workshop who, unlike most of the others, was about my age. (Note: Most children of survivors were born after World War II or the 1950s–while I was born in the ’60s so there’s always been this age gap between me and other members of the “second generation,” the term often designated for children of Holocaust survivors).

As she participated in the workshop, this particular performer decided she’d rather write material for the presentation as opposed to acting in it. She asked Brechner if she could do that. He said sure. So she wrote the scene.

(The fact that this scene was not written by the playwright is key to understanding what later transpired.)

I was also in another scene that was inspired by something I shared with the group. During one session, I revealed how when I was 12 years old my father recognized a woman in a photo at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. It was our first time visiting Yad Vashem. The photo showed several women in Liepaja, Latvia, where my father is from, disrobing right before they were about to be executed by the SS. It was a grisly photo, terribly upsetting but sadly one that has become all too familiar and interchangeable in the annals of Holocaust imagery and iconography.

The scene I did was the hired playwright’s nuanced take on that memory I shared except here I was playing a character who, while visiting Yad Vashem, becomes overwhelmed by the photo her father told her about, which she sees.

She gets no comfort from her husband or her friends, all of whom are more outwardly concerned with shopping or where they’re going to eat afterwards. Instead an Israeli acquaintance offers her the comfort and acceptance she so desperately needs.

The presentation was done to a closed house. I invited the son of a close family friend, who shall remain nameless, a famous multiple-Tony Award-winning theater director and former actor, to see the show. Because he was the child of two Holocaust survivors, I thought it might appeal to him. And yes, I thought his attendance and possible approval might be the imprimatur needed to coax Brechner to move the show to an actual run.

He did attend and everyone was thrilled at his presence. He thanked me profusely for the invitation and advised Brechner not to make the show slick or polished in any way. To paraphrase the family friend’s son, it was important to keep the show raw because much of the show’s sheer power and innate poignancy stemmed from our being real-life children and grandchildren of survivors. We were the real thing–not a facile impersonation.

Well, we did get a summer run. And I’d love to tell you that the family friend’s son’s approval of our project was what did the trick. But that wasn’t it. What did the trick was a legal battle that Brechner was having with a prominent nonprofit theater company that owned the space and wanted to get it back. To assert his supremacy over the space, Brechner thought it would be an expedient move on his part to stick a show in there in the meantime. Enter our show, which was called “Children Of.”

Okay, the motive behind the run wasn’t that pure. But we didn’t care. Our special show was going to have a run, even a limited one at that. Hooray! I was going to get a credit at an off-Broadway house. Even better, I was finally going to be able to convey my feelings about my father’s experience within a creative context. A double whammy!

The run started off very well. Brechner enlisted the services of a publicist that AJT frequently employed, a very talented, genial fellow who has since enjoyed a lot of success as a producer. Press releases were written and sent out. Critics from the Jewish press got invites in addition to many Jewish organizations, most notably the newly opened Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.

A rep from the latter organization showed up to see a performance and told Brechner afterwards that he wanted us to perform at the museum. The only problem was that it might take up to a year for that to happen as the theater at the museum was still under construction.

Responses to the show had been unanimously positive. Although the acting ability of the performers ranged in quality, there was no mistaking the raw visceral power of the work, which my family friend’s son saw at once and warned Brechner not to sully with undue commercialism.

Then three weeks into the run, Brechner pulled the plug. A rep from Actors Equity had been to the show and knew that a few of us were members of the union. Maybe it was arrogance or just a lack of forethought being that he probably never expected to give the show a run at the theater had it not been for the aforementioned fight he was having with another theater, but apparently Brechner has never contacted the union to get their permission for the specific performers to appear. So it was over–for the time being.

Rather than continue with us, Brechner gave us a long list of the Jewish organizations that had been interested in us performing at their venue. We got the hint and decided to move on separately from him.

Unfortunately, as soon as Brechner removed himself from the project, that’s when things went awry. Power struggles ensued, egos flared and arguments erupted. It was truly the embodiment of the old cliché about the inmates taking over the asylum. To try and restore order and move the production along, a few people, along with the playwright, seized control. The only problem here was they did not share the same artistic vision that the others had about the production.

The playwright, for instance, hated the scene that I was in–the one he didn’t write. Although he loved the acting in it–he said the writing was bad. So that was out. And it should come as no surprise the actress who wrote that scene was so incensed she left in a huff.

Without asking others for their input, this cabal revised, tweaked and excised everything that they deemed to be unpalatable for whatever reason. Of course, this action resulted in quite a few objections among the ranks that weren’t part of this self-appointed oligarchy. I remember seeing two men in the group come to near blows before being forcibly separated by others.

What buoyed them forth was the resounding support they or rather the production had generated from VIP supporters, which included a famous Jewish conductor/composer who told us he wanted to help us after seeing us perform at a festival in Long Island and a well-known billionaire who had also seen us perform at one of our early post-AJT shows.

The thing is those two VIPs had seen the show in its initial incarnation–before the tinkering, the sanitizing, the oligarchy rewrites, the gutting. Before the show morphed into a canned, antiseptic, super slick, super polished infomercial–the antithesis of what my family friend’s son had warned Brechner about when he first saw the show in its first closed presentation.

Six months later, most of the original cast had been purged, replaced with actors who had no visceral connection to the Holocaust. It wasn’t their fault. They needed a job. But there was no denying that so much of what originally imbued the show with wrenching power and momentum was gone.

I remained…but only with the implicit understanding that I would agree unconditionally with the oligarchy’s wishes.

In the end, I, too, was tossed out following a few disagreements I had with the playwright about a scene.

After they fired me, I apologized to my father for my failure. He told me not to blame myself. It was just a show. “No, it wasn’t,” I insisted. “This was my tribute to you,” I thought to myself but never said to my father although I’m sure he knew it.

I wish I could tell you that after they sacked me, I had heard the last of them. But sadly, they would stalk me for a few more months. They left messages on my answering machine telling me they owed me a little bit of money. They were probably right but I didn’t care. The experience was so toxic and unedifying that It felt like blood money to me at that point. Besides I wanted nothing more to do with them. So I never responded, which only made them more furiously insistent on getting in touch with me. Ah, but they didn’t know that this is one stubborn Leo so I was immutable in my resolve to freeze them out. Thankfully they stopped trying to get in touch with me.

And yes, they did make it to the Holocaust Museum but at that juncture, the show barely resembled what it originally was and everyone, save the oligarchy, was gone.

Following that awful experience I still acted a bit here and there: I did a few more showcases, did some extra and under-five work on soap operas and even put together a one-person piece that I wrote, which was really nothing more than a variety of characters I wanted to play. Very few people showed up for the latter. But then, it didn’t matter because I knew in my soul I was no longer as engaged or as enthusiastic about acting as I was before the “Children Of” mess. I was lumbering through the motions.

It sounds so trite and so over-the-top but I discovered what I needed to do while visiting the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem the summer of 1994. My mother invited me to go with her and my father to Israel to see the family. So I went. I knew I needed to clear my head and just rethink a future that seemed so devoid. Truly, I was lost and dispirited.

As I leaned against the sun-drenched gold stones, the remnants of Herod’s great temple and supplicated for a shred of insight, anything that would help me decide what to do with the remainder of my life, I had a revelation: Why not revive that long buried dream to be a journalist and attend Columbia Graduate School of Journalism? It’s what I secretly and always ached to do. I had never told anyone that but it was true. Heck, when I was a senior in college. I even called the “J-School” (the school’s nickname) and got an application, which I duly filled out via a Selectric typewriter. Only I had never sent it in because I was scared I would be rejected.

For some reason that I’m sure has a baffling psychological dimension to it, one that I’m ill-equipped to dissect and explicate, I felt more perversely comfortable experiencing constant rejection as an actor because that was a certainty. But this was different–it’s what I had always yearned to do -even more than acting–and what I always felt deep down inside I was more temperamentally, intellectually and spiritually better suited for.

So off I went. I applied twice to Columbia. The first time I was rejected because I didn’t have enough experience. I was advised to get a year of experience before reapplying, which I did two years later. This time they took me.

Ironic how my first job out of journalism school was writing about technical theater and later writing about the creative components of theater. It gratified me because it felt like all those experiences I had as a struggling actress, culminating with the “Children Of” nightmare, had some substantive value. I could finally parlay the knowledge I had about theater, even the bad “Children Of” experience into my job. And so I did–very happily.

October 18, 2015

“Steve Jobs” Movie – Very short review

Here is my brief Reader’s Digest review of “Steve Jobs,” a movie about the late iconic Apple co-founder and visionary.

The acting is excellent, particularly Michael Fassbender as Jobs (who looks nothing like the late iconic Apple co-founder and visionary), Kate Winslet as his long-suffering marketing maven/sparring partner and Seth Rogen as Steve Wozniak, whom Jobs co-founded Apple with. The script is fast-paced, full of snappy repartee–a trademark of an Aaron Sorkin screenplay. But with its three-act narrative structure that focuses on Jobs before three product launches at three different time periods–1984, 1988 and 1996–it becomes incredibly repetitive and monotonous to watch with Jobs having the SAME argument with the same people during those specific timelines.

Not the definitive film on Jobs by a long shot. Recommended but with reservations.

Photo courtesy of wikipedia.

Check Out Brief Excerpt From My Book "Love, Loss and Longing in the Age of Reagan"

From Chapter 8:

I was mesmerized by Chloe’s adventures but also a little jealous. My virginity was becoming a grievous burden and a source of shame. I wanted to get rid of it but how? I was not unattractive but I was timid when it came to my body and awkward with expressions of physicality. Outside of a peck during a game of spin the bottle when I was nine years old and an awkward smack on the lips during a bad date in high school, I had barely been kissed. I felt myself a walking embarrassment to myself, my peers, NYU and the sophisticated life I wanted to have and emulate. Would Anais Nin and Gloria Steinem be so mousy and maladroit? I don’t think so.

Drugs might not have helped me unfasten this invisible chastity belt squelching my erotic existence but I did see them as a way of gaining insight into life’s true secrets. Except for pot, which I adored but never purchased, always relying on the kindness of strangers and friends to ply me with it, I never really developed a passion for narcotics. But I didn’t refrain from using them to satisfy my curiosity or to keep me up if I had to cram all night for a final the next day.

Sometimes, it would backfire. Like one time, Chloe gave me a “caffeine pill,” when I told her I needed to stay up all night and finish an English history paper due the next afternoon. I took that “caffeine pill” alright—and then proceeded to clean and vacuum our dorm room—twice—before throwing on my mini gold lame dress and galloping off to Danceteria, a then popular club located nearby.

But I had always been curious about LSD. My rock heroes, the Beatles and the Who, had taken LSD and had spoken at length about its effects. I wasn’t interested in taking the drug on a regular basis; I just wanted to see what the big deal was with the drug and take it just once. Even if I would remain a virgin always (the thought palled), at least I could gain experience in other areas to make me the quasi-rounded woman of my dreams.

“Acid is great, Edie,” Peter said to me over dinner when I told him I was interested in taking it. “It’s truly like no other drug. It’s like a truth serum—the way it clarifies your feelings—about everything. We should take it together.”

Unfortunately, that never happened because Peter had always devised a string of barely plausible excuses for us not to do it together. We would plan to do it and yet again something would come up on Peter’s end to derail it.

Around this time, Chloe and I began going to the clubs on an almost nightly basis. Monday night it was Danceteria, Wednesday was the Pyramid, Friday was the Ritz and Saturday it was Danceteria again, (our favorite club) or another new hotspot. For me, those nights were bathed with a perfume of sweetness so airy and intoxicating I felt like I was floating in my own cloud. Pot and Quaaludes only deepened the pleasure. As the strobe lights poured over our bodies and everyone else in the club, limbs writhing, conjoined in a human tangle, I would look at Chloe and smile. I had never felt so alive. This was the reason why I came to New York. To feel like this. Always.

October 17, 2015

Great article in the New York Times! “The Lonely Death of George Bell”

Probably one of the best articles I’ve read in the NYT in ages! This story really touched me and also put a little fear in my heart because I wonder, as a single woman, if this will be my fate as well.

Click here to read the article.

October 15, 2015

Thursday Flashback Memory: Soft Cell – “BabySitter” – 1981

This song and especially this band remind me of my callow, fallow college years. No doubt it’s a song that Edie and her friends heard all the time when they were hitting the NYC clubs in the early 1980s. Certainly, it’s one I heard all the time as well.

Challenges of Writing in the Not So Long Ago Past

To find out what I did to help me remove the memory blocks, check out the remainder of the post: http://writerwonderland.weebly.com/go...

http://writerwonderland.weebly.com/go...

Ten Things You Don't Know About "Love, Loss and Longing in the Age of Reagan: Diary of a Mad Club Girl"

*Edie and I share many commonalities. Like me, she’s from suburban Northern New Jersey; she’s Jewish, bookish, loves the Who and the Beatles; and is the daughter of a Holocaust survivor and a first-generation Israeli woman. But there are differences: even when she’s making the wrong decisions, Edie is infinitely more intelligent, thoughtful and rational than I was when I was in school. I was a twit, to put it kindly. Edie’s a streamlined college version of me.

*And, yes, NYU’s Sociology Department did offer a class called “Society and Sexual Variations,” which I (like Edie in the book) took to fulfill my sociology minor. And yes, like Edie, I ended up writing a paper on bestiality after not being able to find that much information on my initial choice—necrophilia. Penthouse’s Forum section was a treasure trove of information on bestiality, I kid you not.

To find out the other eight things you don't know about the book, check out:

http://www.mythicalbooks.blogspot.ro/...

http://www.mythicalbooks.blogspot.ro/...

October 14, 2015

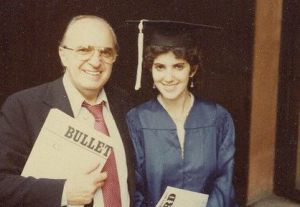

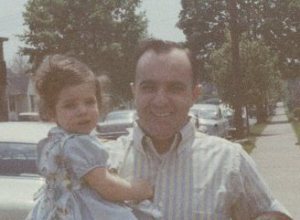

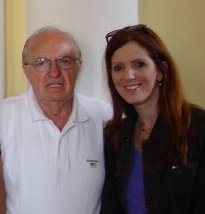

RIP Hirsch Dorbian (1930-2010): Remembering a Wonderful Dad

Five years ago today, you left us and even though we’ve moved on because we’ve had no choice, you will never be forgotten.

Hope you’re doing well in that toolroom in the sky.