Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 996

May 25, 2012

A Sunday Classic: Thanking Hal Jackson

A Sunday Classic: Thanking Hal Jackson by Mark Anthony Neal

By the time I first encountered Hal Jacksonin the mid-1980s—regularly tuning into his Sunday Classics broadcast on New York’s 107.5 WBLS-FM—he had long been established as the cultural pioneer that we celebratetoday. As a kid growing up in the Bronx, literally in the shadow of Hip-hop, my own musical taste were drawn to the burgeoning mix of urban and street music that the now defunct 98.7 Kiss-FM (WRKS) was cultivating; Hal Jackson and WBLS were my parents’ music—so I thought.

And it was perhaps, out of respect for my parents, particularly my dad, for whom Sunday mornings were as precious as any time of the week (though ne never set foot in a church), that I began to listen to Jackson’s program. I very much remember hearing Jackson spin Brook Benton’s “Rainy Night in Georgia” (1970)—a record my father, a Georgia native, wore out during my childhood—and watching the visible reaction on my dad’s face. Music was the bond that my father and I shared, and as I grew older and my dad and I had less contact with each other, Hal Jackson’s Sunday Classics (and New York Met games) became the space where we connected.

When I first started listening to Hal Jackson, I had already begun to show scholarly interests in the study of Black music. There were few classes that I could take in college at that time—Nelson George had yet to publish Where Did I Love Go? (1985) or The Death of Rhythm and Blues (1988)—so WBLS, specifically Vaughn Harper’s Quiet Storm and Jackson’s Sunday program, became my learning lab.

I recall one Sunday morning in particular, when Jackson played a track from Jimmy Scott’s version of “Unchained Melody” (The Source,1969). At the time I was unfamiliar with Scott, a singer most well known for his ability to naturally sing in registers we typically assign to women; I actually thought it was Nancy Wilson that I was hearing, and was shocked to find out that it was a man. When Jackson later played Dinah Washington, an artist who inspired and was inspired by Scott, and who was a particular influence on Wilson and a young Aretha Franklin (during her early years on the Columbia label), I realized that he was simply having school; I never failed to miss class if I was anywhere in the vicinity of WBLS’s signal. I am sure there are many others who can say the same.

When I starting doing radio in the early 1990s—hosting a show called Soul Expressions on Sunday morning for WCVF-FM in Chautauqua County (New York State), I borrowed from Jackson’s (and Harper’s) playbook, using Miles Davis’s “Someday My Prince Will Come” as the musical bed when I addressed the audience (Harper frequently used Joe Sample and David T. Walker’s “In My Wildest Dreams” later sampled for Tupac Shakur’s “Dear Mama”).

During those years at WCVF, I liberated quite a few recordings—long forgotten—as those records became the raw materials for the dissertation that I was writing, later published as my first book What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Black Public Culture (1998). Yet as I went through those stacks, trying to piece together a framework for the Black music tradition and popular resistance, it was always with the critical sensibilities that Jackson and SundayClassics equipped with that I did that work.

Years later, whenever I was in New York visiting my parents, it was not unusual for me to seek out Jackson’s Sunday Classics. The show expanded at various points from those early days, and Jackson often ceded control to Clay Berry & Debi B as he got older—but still, he never failed to teach his listeners something of value about the music and the communities that helped to create and sustain it.

To be sure there were other folk who influenced my work in this regard; the aforementioned Vaughn Harper, the late Gerry Bledsoe, the late Frankie Crocker, Imhotep Gary Byrd, the late Chuck Leonard, Felix Hernandez and his Rhythm Review, and Bev Smith (remembering her BET talk show), who along the late Gil Noble were direct inspirations for the work I do with Left of Black—were also majors figures for me. Yet, I always go back to Hal Jackson, who taught me more than anything about the value of passion, professionalism, stamina and longevity; may he rest in peace and his legacy continue to inspire.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five books including the forthcoming Looking For Leroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities (New York University Press). He is professor of Black Popular Culture in the Department of African & African-American Studies at Duke University and the host of the Weekly Webcast Left of Black . Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan.[image error]

Published on May 25, 2012 09:06

May 24, 2012

Post-Whiteness

Post-Whiteness by Darnell L. Moore | Huffpost BlackVoices

Many Americans are invested in the idea of a "post-racial" moment -- a moment marked by our purported movement beyond a historical chapter colored by race-based discrimination, intolerance, inequity, and violence. Such a turn signals America's fascination with the notion of a transracial future and a utopian vision of an America, where bodies will be free from racialization. But, we must ask: whose bodies and lives will this grand social vision benefit especially when considering the counter-investment in notions of "blackness" that post-racial propagandists seem to maintain?

It is argued that multiple gains have been made in the area of racial relations since the culmination of the Civil Rights Movement. Many of us witnessed the appointment of our country's 65th and 66th Secretaries of State, General Colin Powell and Condoleeza Rice, the former was the first African-American and the latter was the first African-American female, both were Republican. An African-American man and woman, Bob Johnson and Oprah Winfrey, both notable African-American entrepreneurs, have appeared on the Forbes Billionaire List. To the astonishment of the international community, America was brave enough to elect a bi-racial or Black (or, non-White) man, Barack Hussein Obama, as the 44th President of these United States. And, now our nation's capital is home to the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial and will soon be the home of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is scheduled to open officially in 2015. For some, these few moments evidence racial progress, particularly those of African Americans in the twentieth century.

To be sure, Daniel Schorr, NPR Senior News Analyst, noted in 2008 that America was moving into a "post-racial era" that was defined and "embodied" by Barack Obama. He went on to argue that we are in an "era where civil rights veterans of the past century are consigned to history and Americans begin to make race-free judgments on who should lead them." Schorr connects post-racialism to the ascendancy of Obama, a multi-ethnic brown African-descended man, and not, say, his then opponent, John McCain. The fact that Obama is cast as the catalyst of this post-racial era illuminates what post-racialists understand as that which is in need of e(race)sure, namely, blackness. It is unsurprising, then, why post-racialism is a concept that has been taken up to talk about one's transcendence from blackness into a state of being where his/her blackness is "blurred" or ceases to be altogether.

But imagine, if you will, a societal advancement of the notion of "post-white." If you tried, to no avail, to imagine -- like I did -- an America that sought to intentionally and aggressively move beyond whiteness, don't be alarmed because it is a feat that is nearly impossible.

"Whiteness" is an enduring social force that produces a racialized system of access/excess. Those with access have phenotype, structure advantages, and racial legacies to thank. But it is also, as Judy Helfand suggests, that which "is shaped and maintained by the full array of social institutions -- legal, economic, political, educational, religious, and cultural." In other words, whiteness is methodically sustained through ideology and praxis. It is not easy to disappear and, I am pretty certain, that there are many White post-racialists who would rather not live in a post-white moment because the legal, economic, political, educational, religious, and cultural benefits assigned to their whiteness would be no more.

The notion of post-whiteness, or the leaving behind of whiteness as we've come to know it, might very well provoke fear and anxiety among some. For example, the Eagle Forum, which is an interest group started by the conservative anti-feminist Phyllis Shafley, released a legislative alert in response to the New York Timesstory, "Whites Account for Under Half of Births in U.S." The "alert" cautioned, "NY Times liberals seek to destroy the American family of the 1950s, as symbolized by Ozzie and Harriet. The TV characters were happy, self-sufficient, autonomous, law-abiding, honorable, patriotic, hard-working, and otherwise embodied qualities that made America great." The only descriptor that remains loudly unpronounced on the Eagle Forum's list of positive characteristics is the racial identity of both Ozzie and Harriet.

Despite the racial anxieties of our present moment, it is time for Americans to investigate what it might mean for us to consider post-whiteness as an idea and material possibility during this so-called post-racial era. I would sign on as a proponent. We could even ask Tim Wise to lead the way as we begin interrogating the ideas (and advantages) of whiteness as they manifest in these United States and around the world. I long for the day when the Mitt Romneys of the world will argue for a move in the direction of a post-racial, or, rather, a post-white moment: a moment when White racism is really called out and destabilized; a moment when the vestiges of skin privilege are diminished; when real-time material conditions like wealth accumulation, criminalization, and poverty aren't disproportionately shaded by race. Oh, what a day that would be.

Colorblindness, as Schorr intimated, is not the issue. Indeed, the only "color" that seems to move undiscerningly among post-racialists is whiteness. And it's not White people alone who have made such a turn, see, for example Touré's Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness? or Ytasha L. Womack's Post Black: How a New Generation Is Redefining African American Identity. In most cases, blackness is the"color" that we are beckoned to transcend in this post-racial era which is why it is a fallacy to name it such. We are more embedded in the socially constructed categories of race than ever before. Don't believe me? Ask the Tea Party or check the US Census Bureau's statistics on the median incomes of whites in comparison to black and brown folk in our country. Take a look at the number of non-whites who make up our prison and death row populations. Ask the livid "Hunger Game" fans who vented on Twitter because the film's director cast a young African-American actress, Amandla Sternberg, rather than a White actress to play the role of Rue. Or consider the psychic traces of race/racism, the ways in which racism shaped our settler-colonial state and its laws, and the ways we embody and live out race-thought every day.

The point is: America's troubled past and complicated present is wedded to the social reality of race. American history serves as a reminder of our country's troubled race relations and even the moments when difference was celebrated. Americans also know, all too well, that whiteness functions as a non-race that does not require bodily and cognitive transcendence. Similarly, White racism and White privilege show up as non-issues that are eagerly critiqued, yet, rarely undone. Therein lies the problem.

Whiteness travels in stealth; it is supplemented by what anti-racist feminist Peggy McIntosh, writing on White privilege, unforgettably names the "invisible knapsack." The fact is: that "knapsack" has been quite visible in the lives of native and non-white Americans. It has only been invisible to those who carry the weightless knapsack on their backs. Indeed, the burden of the sack is felt by everyone but the bearer. It seems, then, that there is a need for new interrogations of our present racial moment. This may very well be the perfect moment for us to enter, as opposed to transcend, America's racial imagination.

How's that for a postulation?

***

Darnell L. Moore is Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, New York University.

[image error]

Published on May 24, 2012 18:58

Sportin' Life aka David Alan Grier Discusses Porgy & Bess on 'Our World' w/ Marc Lamont Hill

BEMultiMedia

Black Enterprise talks to David Alan Grier about Porgy & Bess on Broadway, on the Our World with Black Enterprise show, with host Marc Lamont Hill.[image error]

Published on May 24, 2012 18:01

The Savior Syndrome: Patrick Willis and the Mystique of #WhiteLove

Patrick Willis' Two Dads | Ruth Fremson, NYTimes

Patrick Willis' Two Dads | Ruth Fremson, NYTimesThe Savior Syndrome: Patrick Willis and the Mystique of #WhiteLove by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

There is an epidemic of white love in America. From The Blind Side and The Help to Kony 2012, George Clooney saving Africa and countless white celebrities liberating black children via adoption, white love has become the antidote to the race problem of the twentieth century. Whereas “the race problem” defined the last years, the next 100 years are purportedly to be one of white love. While racial profiling and the prison industrial complex, persistent discrimination and poverty, education and health disparities continue to plague the nation amid a climate of heightened anti-black racism, immigrant scapegoating, and a rising tide of white nationalists movements, white love offers a ray of sunshine. Better than Barack Obama’s “hope we can believe in,” in the face of so much injustice “white love” is hope (white) society can believe in each and every day.

While watching The Blindside Elon James White highlighted the power of white love within the much celebrated film and society at large:

I DID NOT KNOW WHITE WOMEN COULD CREATE FOOTBALL STARS WITH 16 WORDS. THEY ARE MAGIC. THEY SHOULD BE TAUGHT AT HOGWARTZ!

See--poor Black dude is actually full of talent and wisdom--he just needs a healthy dose of White love to open his eyes. #WHITELOVE

What #TheBlindside teaches us is if White people find poor homeless Black dudes they can create highly sought after football stars.

Awww snap. Kathy Bates and Sandra Bullock are doing a Awesome White Lady TAG TEAM. Hitting him with #WhiteLove left & right...

Dear White People: Please bottle #WhiteLove & sell it. Then we could throw it out of car windows in the ghetto like malatov cocktails...

#WhiteLove is so magical the child of awesomely White Sandra Bullock is smarter & more savy than the poor black dude 10 yrs his senior.

Every White person in this family is AMAZING. The Dad who wasn't even paying attention to poor black dude is now INSPIRING him.

I don't want to watch this movie anymore. I HAVE DEADLINES--but #WhiteLove is drawing me in... I WANT SANDRA BULLOCK SAVE ME.

The power of white love isn’t unique to Hollywood fantasy but is commonplace within sport culture. This particular fantasy was on full display during a recently re-aired episode of ESPN’s E:60. Documenting the trials and tribulations of the 49ers Patrick Willis, whose life took him from a Trailer Park in rural Tennessee to the fame and fortune of the NFL; from poverty and abuse to the American Dream.

The “rags-to-riches” and pulling oneself up by shoelaces is nothing new to sports culture given the centrality of the American Dream and sports as economic escalator within sports media. Yet, the presented story of Willis is one less about the Protestant work ethic and more of white love. The story isn’t so much of his talent, hard work, intelligence, but the transformative power of whiteness, whereupon Willis life changed when he became part of a white family.

The story given on ESPN and elsewhere is rather simple: Willis and his siblings grew up poor in Tennessee. As a result of their mother leaving them and their father’s drug and alcohol problems, a difficult childhood became one of great pain and suffering because of physical abuse. Ultimately standing up to his father by first responding to the abuse and then telling school officials, the children faced the prospects of being split apart. This would never come to fruition as Willis’s coach, Mr. Findley, after a request from the school superintendant, agreed to take all 4 children into their home.

No longer subjected to violence and poverty, yet together as a family, Willis began to thrive on and off the field. According to E:60, he no longer needed to focus on “basic needs” because of his father’s addiction or fending him beatings but instead could be a “normal child.” He was now able concentrate on himself on and off the field. Allowing Willis for the first time to experience love and a true childhood, Willis blossomed into an exceptional football player and even better story. The narrative frame that imagines blackness as pollutant and danger, as problem, juxtapose to whiteness as savior, as help, as goodness, and love is wrought with history and meaning. The only better than Hollywood’s vision of white love is the purported real thing.

Yet, at the same time it celebrates the power of whiteness, the narrative offered celebrates poverty and injustice as the basis of his drive, the foundation of his work ethic, and the impetus for his success. “Boss [Patrick Willis] has never been one to cry, at least not in front of Orey, his 8-year-old brother. Folks around tiny Bruceton, Tenn., say he's 10 going on 25. The kid plays tackle football against men and does all the cooking for his motherless family,” wrote Bruce Feldman a few years back. “During the summer he's out of the house by 6 a.m., gone to chop cotton on the other side of the county in sticky 95° heat. For that, he gets blisters the size of bottle caps on his hands and $110 a week. Orey, baby brother Detris and little sister Ernicka don't call him Boss without good reason.”

In “Patrick Willis: 49ers Star Overcomes Mind-Blowing Adversity on Road to Glory,” Ryan Rudnansky furthers this celebration of injustice as part of his ultimate success: “Given the circumstances of his youth, Willis could have easily quit early. He could have easily slipped down the wrong slope. Instead, Willis used it as motivation to not repeat the same mistakes his father made. Now he has a mansion and a place for his family to visit.” In other words, the poverty the family experienced, the pain he experienced because his mother deserted him and because of his father’s abuse, and the responsibilities that led him to cook and work in the cotton fields at an early age is the reason why he is so successful as athlete and person. His drive and passion comes from these terrible circumstances.

The fetishizing of poverty and the implicit celebration of social ills and injustice as the necessary path to the American Dream is a telling reframing of privilege and opportunity. The absence of opportunities and adversity in the end provides the requisite discipline and work ethic needed to succeed. That plus a little help from benevolent white saviors are the tickets to the promise land. Poverty plus white love are the requisite tools for the American Dream. The hegemony of a narrative of white saviors and romanticized adversity should be of little surprise given its cultural power evidence by The Blindside.

The opening moments of The Blindside establishes it’s overtly racial narrative with amazing clarity. Michael Oher is traveling with a friend, who is hoping for admission into an upscale catholic school; they are leaving a world of poverty and violence within Memphis heading right for an upper-class suburb. As Oher moves from world to the next, the film juxtaposes images of black poverty and despair in opposition to those of white fathers playing ball with their kids. Opportunity exists elsewhere and Oher nearly needed to leave a world of pain and suffering behind. Whereas other black youth would likely be subjected to scrutiny from security and profiling from police responsible for protecting and serving the white middle-class, Oher easily moves into the white world because he is lovable and different.

Michael is acceptable and even desirable because he isn’t threatening (unlike his peers); he is helpless and hopeless – someone in need of saving by white love. He is welcome to enter the white world because not only does he need to be saved and because he is a validation of the superiority of whiteness but because he is safe, lovable, and just not like the others. He is “mute, docile, and ever-grateful to the white folks who took him in.” As noted by Thaddeus Russell, Oher is imagined as a black saint who protects his white family and his white quarterback from danger. More importantly, he is a saint because he is different. “Though raised in Memphis housing projects, he uses no slang and dislikes the taste of malt liquor. Instead of Ecko and Sean John, he wears Charlie Brown-style polo shirts,” writes Russell. “His table manners are impeccable. He exhibits virtually no sexual desire. He is never angry and shuns violence except when necessary to protect the white family that adopted him or the white quarterback he was taught to think of as his brother. In other words, Michael Oher is the perfect black man.”

While still needing white help, Michael, like Patrick Willis, deserves this help because unlike the OTHER they are “the perfect black men.” His perfection will in the end redeem white America, from the Touhys' to the millions of white Americans celebrating this film, from Patrick Willis adopted family to the millions of fans who celebrate his story.

Central to each of these representations is their inscription of sport (and whiteness) as an instrument of values, as a vehicle for opportunity, and as a source of white love. As C. Richard King and I argued in Visual Economies of/In Motion, sports films, including those spots on ESPN, “hails citizen-subjects: at once, they can, with ease and almost complete transparency, inspire audiences, champion individualism and the American dream, reinscribes common sense ideas about race, gender, and sexuality, comment on social issues, and rework the past” (p. 3).

The spot on Patrick Willis and The Blindsidehighlight the imagined place of sports (football) as a bridge between the black and white world, as a source of unification between these disparate worlds, and as ultimately the source of the American Dream. While some may scoff or deny this analysis, noting the truthfulness of these stories, yet the question remains why are these stories told and not others, one not bound together by white love and white saviors. In the end, what’s white love got to do with?

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. Leonard’s latest book After Artest: Race and the Assault on Blackness was just published by SUNY Press in May of 2012.[image error]

Published on May 24, 2012 11:16

Trailer: The Harvard Fellow--9th Wonder @ Harvard

About this project SYNOPSISThe Harvard Fellow follows one of hiphop's most dynamic artists, 9th Wonder through a year of lecturing and research at Harvard University. While at Harvard, 9th will have an office on campus, teach a class on the history of hiphop, complete a research project and further explore hiphop's history and culture in an academic setting.

HISTORYIn November 2011 we screened our first film The Wonder Year at Harvard University. After the screening 9th was asked to apply to become a Harvard Fellow the following year. In March 2012 he received the acceptance letter to the program and the concept for the second documentary began to take shape.

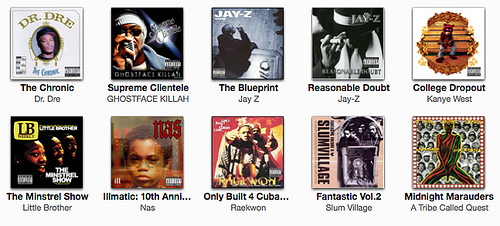

RESEARCHPart of 9th's requirement as a Harvard Fellow is to complete an academic research project that will be placed permanently in the Harvard Library. For 9th's research project titled "These Are The Breaks" he will be researching the original records that created his top 10 produced albums. For example, 9th will track down all the original records that were sampled to create the ten tracks of Nas's Illmatic. Those records will then be catalogued and archived in the permanent collection at Harvard. While record digging we will meet with the producers who helped craft these classic albums.

The albums are: Dr. Dre "The Chronic," Nas "Illmatic," Jay Z "Reasonable Doubt," Little Brother "The Minstrel Show," A Tribe Called Quest "Midnight Marauders," Ghostface Killah "Supreme Clientele," Slum Village "Fantastic Volume II," Kanye West "The College Dropout," Jay Z - "The Blueprint," and Raekwon "Only Built 4 Cuban Linx."

WHY MAKING THE HARVARD FELLOW IS IMPORTANTThe film will explore hiphop's place in an academic setting and why it is important to protect and archive its history. There has never been an active member of the hiphop community who has spent a year immersed in the the study of hiphop at an Ivy League school like Harvard University. Making this film will allow audiences around the world to experience this important academic and cultural journey alongside 9th Wonder.

WHY MAKING THE HARVARD FELLOW IS IMPORTANTThe film will explore hiphop's place in an academic setting and why it is important to protect and archive its history. There has never been an active member of the hiphop community who has spent a year immersed in the the study of hiphop at an Ivy League school like Harvard University. Making this film will allow audiences around the world to experience this important academic and cultural journey alongside 9th Wonder.PLANS FOR THE KICKSTARTER FUNDSThe money raised from this Kickstarter will go towards purchasing film equipment, mixing the film, travel expenses and film festival submission fees. Even with a small crew the cost of filmmaking quickly adds up and with your help we can create a professional film at a relatively low cost. But we need your help!

For more info visit! www.theharvardfellow.com

Follow us on twitter! www.twitter.com/harvardfellow

Like us on Facebook! https://www.facebook.com/TheHarvardFellow[image error]

Published on May 24, 2012 08:32

May 23, 2012

Jay Smooth: The Real Conspiracy Against Hip-Hop

illdoc1:

This is what THEY don't want you to know. An exclusive analysis of the secret letter that was recently revealed here: http://www.hiphopisread.com/2012/04/secret-meeting-that-changed-rap-music.html

IMPORTANT ILL DOCTRINE NEWS: I've started up a new partnership with my friends at Animal New York to make videos for you more often, and from now on my new videos premiere at this page - http://animalnewyork.com/illdoctrine I'll still be putting all my videos up here too, but only a week or so after they premiere over there. SO bookmark that page, and let me know how you like the new videos!

Published on May 23, 2012 17:17

Firing Line w/ William F. Buckley Jr. with Guest Muhammad Ali

Taped on Dec 12, 1968

Published on May 23, 2012 09:24

May 22, 2012

Media Coverage of Reproductive Rights Should Include Women of Color

Media Coverage of Reproductive Rights Should Include Women of Color by Nadra Kareem Nittle | Maynard Media Center

Social wedge issues such as abortion, birth control and sex education in public schools have taken center stage and sometimes dominated the political debate this year, but progressive experts on reproductive rights are concerned that women of color are rarely represented in the mainstream media’s coverage.

If elected president, presumptive Republican candidate Mitt Romney has vowed to defund Planned Parenthood, a move that the state of Texas is attempting. Moreover, Tennessee has passed legislation to severely limit what educators can teach in sex education classes, and states such as Arizona, Mississippi and Virginia have passed legislation that significantly restricts abortion access.

Conservative attacks on reproductive rights repeatedly make headlines. But women of color and low-income women who disproportionately depend on the services of Planned Parenthood and face challenges accessing reproductive care have not figured prominently in mainstream news coverage of the reproductive rights debate.

Experts on the topic say that because underprivileged women have the most to lose as lawmakers curb such rights, the media should focus on them in the discussion.

“Women who are poor and also women of color have disproportionately high rates of unwanted pregnancy,” says Heather Boonstra, a senior public policy associate of the Guttmacher Institute, a Washington, D.C., organization that advocates for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

“Some of that has to do with the basics in terms of obtaining health care and the kinds of social conditions in the women’s lives that make it hard for them to use contraception and use it consistently,” she says. “Poorer women — their lives have a lot of disruptions. Using and obtaining contraception, let alone affording it and getting it on a routine basis is harder.”

According to the institute, black women are three times as likely as white women to have an unplanned pregnancy, and Hispanic women are two times as likely. Among poor women, Hispanics have the highest rate of unplanned pregnancy. In addition, financial pressures related to the sluggish economy are likely leading more poor women to terminate pregnancies. The institute found that the number of abortion recipients who were poor jumped from 27 percent in 2000 to 42 percent in 2008, the first full year of the economic downturn.

Media outlets tend to ignore these findings and the financial pressures driving them, and simply report on abortion rates and laws without factoring in race and class. Including more women of color and their advocates in mainstream media stories would produce more comprehensive articles.

For instance, Boonstra says a primary reason that poor women have high rates of unintended pregnancies is because they lack access to long-acting forms of contraception, a privilege afforded women with higher incomes and private insurance.

Dependence exclusively on birth control methods that must be used daily or for every sexual encounter, such as pills and condoms, leads to a higher unplanned pregnancy rate among disadvantaged women. Yet pundits and reporters typically don’t mention the impact that current legislation to curb access to birth control, abortion and sex education will have on underprivileged women.

“I think that more African-American women need a turn at the mic to talk about how these issues are impacting the community,” says Janette Robinson-Flint, executive director of Black Women for Wellness, a Los Angeles organization that advocates for health needs of black women. “Major media outlets have a tendency not to have African-American women in anchor or decision-making positions.”

In 2010, the media extensively covered a suggestion by conservative groups, such as the Issues4Life Foundation, that abortion providers were influencing black women to terminate their pregnancies. In major cities, right-wing groups have erected billboards on which they contend that the high number of abortions black women have is tantamount to genocide.

Robinson-Flint says she was dismayed that the media focused on the controversial billboards without delving deeply into factors that lead black women to have abortions at five times the rate that white women do.

“They didn’t talk about the social justice issues,” she says of the flawed reporting. “They didn’t talk about poverty, unemployment, infant mortality, maternal mortality, any of the contributing factors.” She adds that in Los Angeles, for example, hospital closures have resulted in too few medical providers to meet the black community’s needs, contributing to lack of family planning.

Some states have no providers who perform abortions, and legislation pending in Mississippi would result in closure of the sole facility there. Such laws pose the greatest disadvantage to poor, underprivileged women, according to Boonstra, because they already struggle to cover the basic cost of an abortion. Fifty-seven percent of women pay for the procedure out of pocket, the Guttmacher Institute reports.

The institute’s overview of state abortion laws as of May 1 is available at www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_OAL.pdf.

Removing local abortion providers means that poor women also must pay for travel to a state that provides abortions and likely miss work or pay for child care if they are among the 61 percent of women who have abortions and are mothers. These costs may increase if women seek abortions in states that require them to endure a waiting period before terminating their pregnancies. Women in this predicament will likely have to miss more days of work and pay for extended stays in hotels, Boonstra says.

The abortion debate isn’t the only sexual health issue making headlines. Legislation to limit the type of sexual education taught in schools has also received major mainstream media coverage. Often omitted from this coverage is that youths of color deprived of sexual education classes may be especially vulnerable.

Black teens, for example, are twice as likely as whites or Latinos to develop a sexually transmitted infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2008. That figure was consistent even when factoring in income levels and numbers of sexual partners, an indication that these teens are not taught how to practice safer sex.

After a decline in teen pregnancy from 1990 to 2005, the rates rose in 2006 for all racial groups, particularly minorities. The Hispanic teen pregnancy rate rose by 126.6 percent that year, followed by blacks at 126.3 percent and whites at 44 percent.

“There’s plenty of research that shows abstinence-oriented sex education leads to more teen pregnancy and not less,” says Dominique DiPrima, host of Front Page, a Los Angeles radio show. DiPrima focuses largely on issues of concern to communities of color and women. She recently launched the Black Media Alliance, a coalition of African-Americans in media and broadcasting, to encourage the mainstream media to represent people of color more often as reporters, sources and decision makers.

“There needs to be more [discussion] in the media where women are talking with women and not in a defensive posture,” DiPrima says. “A lot of times, you see panels where there are no women. Not to say men should be excluded, but there [need] to be more places where women can have frank dialogue.”

DiPrima says the media rely too often on professional pundits rather than people of color, who are most likely to be affected.

The Black Media Alliance has had discussions with media outlets such as Clear Channel about racism and misogyny on air. DiPrima says she hopes that communities of color learn more about attacks on reproductive rights before pending legislation becomes law and it’s too late to act.

“I believe people are waking up and realizing that Republicans have gone so Neanderthal with their attacks on women,” she says. “They’re uniting women. I think it’s going to wake people up, and the end result may just be the opposite of what they’re planning for the country.”

***

A Chicago native, Nadra Kareem Nittle has written for a wide range of print and online publications since 2000. She’s used her background as an American Studies major at Occidental College to examine issues of race for media outlets such as the Los Angeles Times' Inland Valley edition, the El Paso Times, the Santa Fe Reporter and the L.A. Watts Times. Additionally, her writing has been featured on Web sites Racialicious.com and Racerelations.about.com. Follow her on Twitter.

Published on May 22, 2012 17:38

Left of Black S2:E33 | Race, Writing and the Attack on Black Studies w/ Adam Mansbach & La TaSha Levy on Season Finale of 'Left of Black'

Left of Black S2:E33 | May 21, 2012

Race, Writing and the Attack on Black Studies w/ Adam Mansbach & La TaSha Levy on Season Finale of Left of Black

Host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal is joined via Skype by writer Adam Mansbach, the author of several books including Angry Black White Boy(2005), The End of the Jews (2008) and the New York Times Bestseller Go the F**K to Sleep. Mansbach discusses the inspiration for Macon Detornay—the protagonist of Angry Black White Boy—the surprise success of his “adult children’s book” and his new graphic novel Nature of the Beast. Finally Neal and Mansbach discuss race in the Obama era and the legacy of the Beastie Boys.

Later, Neal is joined, also via Skype, by LaTaSha B. Levy, doctoral candidate in the Department of African-American Studies at Northwestern University. Levy and several of her colleagues including Keeanga Yamahtta Taylor and Ruth Hayes, the subjects of a celebratory profile in The Chronicle of Higher Education, were later attacked by a blogger at the same publication, raising questions about the continued hostility directed towards the field of Black Studies. Neal and Levy discuss the responses to the attack, as well as her research on the rise of Black Republicans.

***

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in HD @ iTunes U

Published on May 22, 2012 11:12

Jay Smooth: Don't Freak Out About the White Babies

ANIMALNewYork.com:

Jay Smooth helps America adjust to the news that for the first time in history, a majority of American babies born in the last year were minorities.

Published on May 22, 2012 09:13

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.