Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 920

February 15, 2013

Noam Chomsky & Rev. Osagyefo Sekou Discuss Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Chomsky and Sekou on MLK from Rev. Osagyefo Sekou on Vimeo.

Noam Chomsky is a US political theorist and activist, and institute professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Besides his work in linguistics, Chomsky is internationally recognized as one of the most critically engaged public intellectuals alive today. Chomsky continues to be an unapologetic critic of both American foreign policy and its ambitions for geopolitical hegemony and the neoliberal turn of global capitalism, which he identifies in terms of class warfare waged from above against the needs and interests of the great majority.

Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou, Editor-in-Chief of Spare Change News, has published two critically acclaimed collections of essays, 'urbansouls' (Urban Press, 2001) and 'Gods, Gays, and Guns: Essays on Religion and the Future of Democracy' (Campbell and Cannon Press, 2011). His forthcoming book, 'Riot Music: Hip Hop, Race, and the Meaning of the London Riots' (Hamilton Books, 2013) is based on his exclusive interviews in the aftermath of the London Riots 2011.

Noam Chomsky is a US political theorist and activist, and institute professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Besides his work in linguistics, Chomsky is internationally recognized as one of the most critically engaged public intellectuals alive today. Chomsky continues to be an unapologetic critic of both American foreign policy and its ambitions for geopolitical hegemony and the neoliberal turn of global capitalism, which he identifies in terms of class warfare waged from above against the needs and interests of the great majority.

Rev. Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou, Editor-in-Chief of Spare Change News, has published two critically acclaimed collections of essays, 'urbansouls' (Urban Press, 2001) and 'Gods, Gays, and Guns: Essays on Religion and the Future of Democracy' (Campbell and Cannon Press, 2011). His forthcoming book, 'Riot Music: Hip Hop, Race, and the Meaning of the London Riots' (Hamilton Books, 2013) is based on his exclusive interviews in the aftermath of the London Riots 2011.

Published on February 15, 2013 04:29

February 14, 2013

Jay-Z and His Embodied Politics of Respectability

Touch the Untouchable…Do the Impossible: Jay-Z and His Embodied Politics of Respectability by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“Can't touch the untouchable, break the unbreakable / Shake the unshakeable (it's Hovi baby) / Can't see the unseeable, reach the unreachable / Do the impossible (it's Hovi baby)” —Jay-Z “Hovi Baby”

Nas and Jay-Z were both present at this year Grammy Awards, the premier awards ceremony in the music industry, which celebrates the yearly accomplishments and highlights all music genres. The Grammys are to the music industry what the Oscars are to those in the film industry. And while the rappers (Nas and Jay-Z) both donned a tuxedo that is where the trajectories of their respective careers intersect and depart. Nas has been nominated 18 times for a Grammy and has failed to win one, while Jay-Z further added to his total by winning in the category for “Best Rap/ Song Collaboration” for his song “No Church in the Wild” which features guest appearances by Frank Ocean and The Dream, alongside his “The Throne” collaborator, Kanye West. While what proceeded was referred to as the “zinger of the night,” Jay-Z’s rather dismissive comments directed at singer the Dream demand a closer reading, one that extends beyond his already substantial, and growing, Grammy collection.

When responding to a question centering on the differences between Jay-Z and Nas, a friend of mind offered, “If Jay-Z is the dream, Nas is the work…” While such a comment offers much food for thought and critical engagement, the words allude to some of the topics that are taboo and fraught with tensions within hip-hop culture. At a minimum, it was suggested, Jay-Z’s music represents the kind of aspirational sensibilities that is arguably embedded in the American ethos of reform, transformation, and, ultimately acceptance. It entails a Horatio Alger-like pulling of oneself up by the bootstraps, in the making and remaking of one’s success and push towards the mainstream. The latter half of that comment suggests a kind of blue-collar wisdom and work ethic that is the everyday experience, complete with thoughts and sentiments about a range of topics that firmly establishes the everyday person as someone equally invested and interested in the occurrences and events of the world around them.

The comment—“I would like to thank the swap meet for his hat”—is precisely a manifestation of a politics of respectability that seeks in this instance to monitor, comment, admonish, and draw attention to the kinds of difference that are socially and culturally constructed and contested as normal and proper. Here a politics of respectability, as conceived by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, points towards a discourse of assimilation that stresses the importance of black people’s (public and private) adherence to morals, manners, and modes of self-presentation consistent with those established and followed by dominant society. This stance on public reform effectively ties the actions, behaviors, attitudes, and very disposition of the individual to the larger collective of the group as a whole. Nowhere it is this more evident than in the clothing guidelines released by CBS directed to attendees of the 55th Grammy Awards. While Dean Obeidallah rightly points out that this dress code requirement is far from being gender neutral, the mere language and existence of said dress code seeks to enforce and institutionalize a set of rules that will undoubtedly be internalized, embodied, and performed by some of the attendees.

The question of accountability—“who?” as well as “to whom?”—is fertile ground for critical inquiry. However, the fact(s) of Jay-Z’s dismissal explicitly and implicitly embody a politics of aspiration inherent in hip-hop, and perhaps best embodied in the juxtaposition of the Dream’s jewelry vis-à-vis Jay-Z’s tuxedo. Situating a tuxedo in contrast to jewelry signals the polished and clean cut, and as a direct consequence, the acceptable, as opposed to the gleaming, ostentatious showcasing of the material, embodied and manifested in the attitude, anxiety, and behavior of the Dream. At a minimum, this communicates to a viewing audience the fluidity and variety of ways in which the everyday, let alone the artistic, can be presented and performed in a public setting. It serves as a vivid reminder of the broad range of representations present in marginalized communities on a day-to-day basis. Simply put, rappers don’t seem to be shying away from liking nice things anytime soon. I’d be curious to know if there is room for a discussion of cost, consumerism, and the material as evidenced in the possible differences in price between the two “uniforms.” There is nothing wrong with wearing a tuxedo, or a “suit and tie” for that matter, but there is a glaring problem when narratives become constructed and projected such that those who are already marginal, like hip-hop at the Grammys, are further relegated to the margins. Moreover, what is dangerous and problematic about this juxtaposition of the tuxedo versus the swap meet hat, is a reinforcement of beliefs, ideas, and ideology that constrains and overlooks the complex understanding of self that we naturally embody everyday with regards to our respective identities. Here, hip-hop is policing itself and at a minimum imposing a hegemonic narrative on that which is deemed authentic, and by extension, responsible. One can argue whether or not this exchange falls under the category of “real recognizing real.”

More to the point, there is the possibility of framing this brief interaction as constituting an experience whereby the legibility of Shawn Carter is contrasted with the illegible body of the Dream. Present, though perhaps, lying underneath the surface, is a lens-affording context to the generational gaps within hip-hop. As my colleague Ryan Jobson accurately notes, there is a distinction to be made “between those who have entered the realm of respectability and those who remain beholden to the vernacular, sartorial, and performative code of the street.” A point for further inquiry is an examination that questions the extent to which the Dream is maintaining and pushing the disruptive politics of an organic intellectual, whereas Jay-Z has become normalized in a myriad of ways. This subversive politics characterizes the Dream’s stance, while Jay-Z's panders to dominant scripts of normalcy. The illegible here can be thought of as the impossibility imbedded in discourses of the remarkable, and transcendence as something that is not readily available to most rappers and/or urban contemporary artists. In his transition from the corner to the corner office in the executive suite, Jay-Z has capitalized and transferred his industry acumen in ways that have not been a possibility for artists like the Dream. Music industry aside, corporate culture is more rigid by comparison in its institutionalization and embodied practices that dictate its own politics of respectability.

Furthermore, hidden in this acceptance speech is the construction and performance of a politics of inheritance constituted within a framework of an “anxiety of influence.” While the literary reference established by Harold Bloom was not intended for this occasion, it speaks to Jay-Z’s refashioning and branding as a hustler turned American cultural icon. If we are to decode and unmask Jay-Z, this is the same person who has offered audiences the following lines in several of his songs:

“Change Clothes:” “please respect my/Jiggy/this is probably Purple Label/Or that BBC shit or it's probably tailored/And y'all niggas actin' way too tough/Throw on a suit, get it tapered up…”

“So Ghetto:” “Thug nigga til the end, tell a friend bitch / Won't change for no paper plus I been rich… / We tote guns to the Grammys, pop bottles on the White House lawn / Guess I'm just the same old Shawn”

As a response to Jay-Z’s “So Ghetto” Demetrius Noble points out that:

such defiance and cultural dissidence used to be hallmarks of a once working-class culture and praxis. But Jay (and others) have worked very hard to turn hip hop into a class collaborationist space where such shifts and contradictions are continuously mystified to promote a nationalist fantasy of solidarity. Jay didn't keep up the facade last night however as he was speaking to his bourgeois (and mostly) white audiences. To quote Jay again, "I guess it's only so long fake thugs can pretend."

It is important to highlight the politics of respectability and shifts in both preference and tastes as they were manifested in Jay-Z's dismissal of the Dream. This is very much indicative of the kinds of change Jay-Z has embraced vis-a-vis audience when his live show downplays those same changes. The presence and posture of the Dream would and could very well have been Jay-Z circa 1999, the year he won his first Grammy.

At a live show, Jay-Z is the lived experience embodied in the creative personae of Shawn Carter. Actor and Comedian Chris Rock once joked that his neighborhood was occupied by four exceptionally talented Black people. Rock and Jay-Z were two of those four exceptional Black people, Eddie Murphy and Mary J. Blige, being the others. His neighbor, on the other hand, a white man, was a dentist, and as Rock points out, it is unknown whether he is a good dentist at that. While this joke locates black exceptionalism alongside white-collar normalcy, the point is not lost when thinking about Jay-Z and his sharing the stage with the Dream. Jay-Z’s pursuit, ascendance, and ownership over the throne exposes a discourse of black exceptionalism and exclusion within hip-hop: a mode of presentation distinguishable by dress, posture, presence, and ultimately, influence. Jay-Z is living the (American) dream, while the Dream, both literally and metaphorically, resides in another neighborhood…those where shopping at the swap meet appears pervasive and acceptable.

***

Wilfredo Gomez is a doctoral student in Anthropology and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. He can be reached at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.com or via twitter at BazookaGomez84.

Published on February 14, 2013 18:45

The Love Space Demands: New Mix by DJ lynnee denise

The Love Space Demands by lynnee denise

The Love Space Demands, is a choreopoem published in 1991, by Notzake Shange. In it she returned to the blend of music, dance, poetry and drama that characterized For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide....Her work has been described as sexy, discomforting, energizing, revealing, occasionally smug, and fascinating.”

This is true.

Ntozake Shange forces the kind of reflection that creates discomfort...growth. The first time I heard the words "The Love Space Demands" I paused and dropped everything. That's it. The space, the time, the clarity, the beauty and the pain that holds the hand of growing.

The process of creating a mix is an arduous one. I spend at least 3-6 months listening to each song repeatedly until I figure out the arrangement--the bigger picture. Driven by some of the hardest lessons learned by the heart, my house music rendition of Shange's choreopoem "The Love that Space Demands" asks listeners to consider the inspiring and transformative range of emotions that one can feel when riding through that journey called love. And then there's the letting go and doing it all over again. And i'll do it again. Every time. Heartbreak is an opportunity. Each song tells a story of contradiction, understanding, betrayal, yearning, unconditional love, tenderness and surrender.

Read More

Published on February 14, 2013 15:52

February 13, 2013

What is it Like to be an African-American Muslim in the US Today?

The Stream

What does it mean to be an African-American Muslim in 2013? Fifty years ago, Islam in the US was laid against the backdrop of racial segregation, led by the likes of Malcolm X and Elijah Mohammed. But today things have changed, with Muslim influence represented in pop culture like the hip-hop music industry. Join The Stream as we go in-depth to talk about how the community has evolved.

In this episode of The Stream, we speak to:

Joshua Salaam, @salaamatweet

Singer, Native Deen

nativedeen.com

Zaheer Ali, @zaheerali

Project Manager, The Malcolm X Project at Columbia University

zaheerali.com

Su'ad Abdul Khabeer, @DrSuad

Assistant Professor, Purdue University

Amir Sulaiman, @amirsulaiman

Spoken word artist

amirsulaiman.com

Published on February 13, 2013 20:19

After the Dance: Intimacy in the Grooves

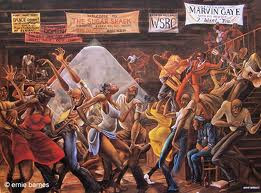

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Times; panose-1:2 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Cambria; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page Section1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style> <br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><b><i><span style="font-family: Times;">After the Dance: Intimacy in the Grooves</span></i></b></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">by Mark Anthony Neal | <b>NewBlackMan (in Exile)</b></span></span><br /><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">It was simply a brief introduction to the career of Rod Temperton, the British born songwriter, who first came to prominence with the group Heatwave. Specifically I was reminiscing about Heatwave’s “Always and Forever,” a classic Soul ode to longstanding love and romance. Unfortunately my class of 60-plus millennials were not quite as excited by the nostalgia that had begun to overtake me. For my generation, “Always and Forever” was part of a ritual of romance, likely the first song we ever slowed danced to—or dragged to as my parents might have said. When I segued into Michael Jackson’s “Lady in My Life”—another Temperton classic—it became clear to me that my students weren’t just unfamiliar with the music, but had no idea what to do with the music, a point that was made when I asked several of them to dance to the song. “What do y’all slow dance to?” I asked; “we don’t” was the emphatic answer. When a few students, offered that they “twerked”—me: “what the hell is that?”—I had to resist the urge to get all sociological about the fact that we are raising a generation of young folk for which sex has became a stand-in for intimacy. And don’t get me wrong, I fully endorse sex—fully and between consenting adults—but intimacy (and the pursuit for it) is one of those things that have sustained Black folk for centuries here in the West.</span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><br /></div><a name='more'></a><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">The fact that many young Blacks don’t slow dance, is as much about their relationship to the music, as it is the<span style="font-size: small;">ir</span> relationship to their bodies. For many Black Americans, music was the site in which intimacy could be realized, and as Angela Davis points out in her book <i>Blues Legacies and Black Feminism</i>, there were political ramifications. Writing about Black life immediately after emancipation, Davis notes “For the first time in the history of the African presence in North America, masses of black women and men were in a position to make autonomous decisions regarding the sexual partnerships they entered. Sexuality thus was one of the most tangible domains in which emancipation was acted upon and through which its meaning were expressed.” (4) </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">With the advent of the phonograph and more access to the private consumption of music, the connection between music and Black intimacy became more concrete. As Davis attest about the Blues tradition that emerges in the 1920s, “the most obvious ways in which blues lyrics deviated from that era’s established popular musical culture was their provocative and pervasive—including homosexual—imagery.” (3). This was the music of a generation of Black folk—two generations removed from slavery and still suffering Jim Crow—for which the sensual and sexual use of their bodies were acts of survival, sustenance, pleasure and even resistance. Though raucous forms of Blues may have had a hearing in publics spaces (where everyone was an adult and up for a goodtime), in many cases this was music intended for consumption in the private spaces of Black life, as was the case with Jelly Roll Morton’s 17-minute “Make Me a Pallet,” which contains the classic line "Come here, you sweet bitch, give me that pussy, let me get in your drawers/I'm gonna make you think you fuckin' with Santa Claus."</span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">Yet there was a public intimacy that was also sought by Blacks, particularly in the dancehall. As playwright Brent Jennings notes in his essay “Initiation of a Desire,” there was a component of public intimacy that was directly correlated to notions of racial uplift. Recalling his first “sexual” encounter in a segregated third grade classroom, Jennings remembers a teacher whose “main desires for her third grade students was that we become perfect gentleman and respectable ladies. She felt that in order to accomplish this, we had to become ‘comfortable with each other,’ so she made the boys and girls sit side by side, adjacent to one another. We were seatmates.” (<i>The Black Body</i>, ed. Meri Nana-Ama Danquah, 110). </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">In another classroom theater, journalist Kenji Jasper recalls a time in 8<sup>th</sup>grade when he trusted a “big butt and a smile,” sitting behind a classmate that he calls “Tosha Jones” and being drawn to what he describes as “Two fudge colored cheeks with a sheet of khaki stretched across, their mass squeezing through the chrome reverse “U” in her chair back.” (<i>The Black Body</i>, 161) Jasper goes on to describe what more than a few of us remember as “the feel up,” both entranced by her ass, and perplexed by her lack of recognition of his groping, until—three minutes later—she handed him a note that stated, “you have to stop now. People are looking.” Taking her note into account, “Tosha’s” silence could at once be read as her investment in comporting herself in a way that “good girls” should—“people are looking”—as much as it might have been an articulation of the pleasure she might have derived from Jasper’s touch. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">Dismissing for a moment the compulsory heterosexual socialization that was also taking place in these stories and the easy ways that “feeling up” can cross the line into predatory sexual behavior (as Jennings admits in his own classroom story), the close proximity of pubescent bodies and sexual desires created the context for that time-tested ritual: the school dance. For young Blacks school dances (and cotillions) were a means of introduction to acceptable public forms of affection and sexual desire, that also hung on notions of glamour, sophistication, and, of course, respectability. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">Yet in another public/private iteration, there was also the house party, in which the private intimacy—the kind that might be outlawed if you were a teen living in your parents’ house—literally morphed into the public intimacy of a living room or basement, amongst a relative mass of folk, themselves pursuing all manner of desire and intimacy. One might recall Luther Vandross singing about “Bad Boy” trying to sneak out the house, <i>to the house party</i>, in a song—“Bad Boy/Having a Party”—that was an extended riff on Sam Cooke’s own celebration of the house party. While Vandross, sings, “roll back the rugs everybody, move all the tables and chairs, we gonna have us a goodtime tonight,” there was always that other moment, a later moment, and often the last moment, when the lights got dimmed—the proverbial “blue light in the basement”—and intimacy was crafted in tight spaces, where partners got to feel the contours of each other’s waist, hips, shoulders…and to literally take in the smell of sexual desire and intimacy. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">And of course there’s the music, preferably a side that pushed towards a 5-plus minute mark, which was a challenge in the pre-digital era, when someone actually had to be in charge of changing the record. The genius of Isaac Hayes was his understanding of such dynamics, hence side-two of his classic <i>Hot Buttered Soul</i> (1969), which only features “One Woman” (5:10) and his seminal remake of Jimmy Webb’s “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” which logged in at 18-plus minutes—or more than enough time for a little public foreplay. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">And then there’s Marvin Gaye, whose recordings <i>Let’s Get it On</i> (1973) and <i>I Want You</i> (1976) were both recorded as extended suites, in which one could experience the full gamut of sexual intimacy. Though <i>Let’s Get It On</i> is the more remembered of the two recordings, in no small part to Gaye’s deliberate blurring of the sacred and the sexual—“something like sanctified” as he sang—<i>I Want You</i> is a masterpiece of unbridled sexual desire. The album begins with the invocation of desire—“I want you, and I want you to want me too”—touring through tracks such as “Feel All My Love Inside,” “Come Live with Me Angel,” and fittingly closing with the vocal rendition of “After the Dance,” as the dance (with the Ernie Barnes’ original “Sugar Shack” providing visuals) was the original site of desire.</span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">There’s no doubt that the young folk will find their own grooves of intimacy—it just won’t look, sound and feel like the intimacy of my youth. For now, I got a playlist loaded with Marvin, Isaac, a little Al Green, Gloria Scott and Teena Marie’s “Portuguese Lover.”…</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><br /></div>

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Times; panose-1:2 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Cambria; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page Section1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style> <br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><b><i><span style="font-family: Times;">After the Dance: Intimacy in the Grooves</span></i></b></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">by Mark Anthony Neal | <b>NewBlackMan (in Exile)</b></span></span><br /><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">It was simply a brief introduction to the career of Rod Temperton, the British born songwriter, who first came to prominence with the group Heatwave. Specifically I was reminiscing about Heatwave’s “Always and Forever,” a classic Soul ode to longstanding love and romance. Unfortunately my class of 60-plus millennials were not quite as excited by the nostalgia that had begun to overtake me. For my generation, “Always and Forever” was part of a ritual of romance, likely the first song we ever slowed danced to—or dragged to as my parents might have said. When I segued into Michael Jackson’s “Lady in My Life”—another Temperton classic—it became clear to me that my students weren’t just unfamiliar with the music, but had no idea what to do with the music, a point that was made when I asked several of them to dance to the song. “What do y’all slow dance to?” I asked; “we don’t” was the emphatic answer. When a few students, offered that they “twerked”—me: “what the hell is that?”—I had to resist the urge to get all sociological about the fact that we are raising a generation of young folk for which sex has became a stand-in for intimacy. And don’t get me wrong, I fully endorse sex—fully and between consenting adults—but intimacy (and the pursuit for it) is one of those things that have sustained Black folk for centuries here in the West.</span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><br /></div><a name='more'></a><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">The fact that many young Blacks don’t slow dance, is as much about their relationship to the music, as it is the<span style="font-size: small;">ir</span> relationship to their bodies. For many Black Americans, music was the site in which intimacy could be realized, and as Angela Davis points out in her book <i>Blues Legacies and Black Feminism</i>, there were political ramifications. Writing about Black life immediately after emancipation, Davis notes “For the first time in the history of the African presence in North America, masses of black women and men were in a position to make autonomous decisions regarding the sexual partnerships they entered. Sexuality thus was one of the most tangible domains in which emancipation was acted upon and through which its meaning were expressed.” (4) </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">With the advent of the phonograph and more access to the private consumption of music, the connection between music and Black intimacy became more concrete. As Davis attest about the Blues tradition that emerges in the 1920s, “the most obvious ways in which blues lyrics deviated from that era’s established popular musical culture was their provocative and pervasive—including homosexual—imagery.” (3). This was the music of a generation of Black folk—two generations removed from slavery and still suffering Jim Crow—for which the sensual and sexual use of their bodies were acts of survival, sustenance, pleasure and even resistance. Though raucous forms of Blues may have had a hearing in publics spaces (where everyone was an adult and up for a goodtime), in many cases this was music intended for consumption in the private spaces of Black life, as was the case with Jelly Roll Morton’s 17-minute “Make Me a Pallet,” which contains the classic line "Come here, you sweet bitch, give me that pussy, let me get in your drawers/I'm gonna make you think you fuckin' with Santa Claus."</span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">Yet there was a public intimacy that was also sought by Blacks, particularly in the dancehall. As playwright Brent Jennings notes in his essay “Initiation of a Desire,” there was a component of public intimacy that was directly correlated to notions of racial uplift. Recalling his first “sexual” encounter in a segregated third grade classroom, Jennings remembers a teacher whose “main desires for her third grade students was that we become perfect gentleman and respectable ladies. She felt that in order to accomplish this, we had to become ‘comfortable with each other,’ so she made the boys and girls sit side by side, adjacent to one another. We were seatmates.” (<i>The Black Body</i>, ed. Meri Nana-Ama Danquah, 110). </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">In another classroom theater, journalist Kenji Jasper recalls a time in 8<sup>th</sup>grade when he trusted a “big butt and a smile,” sitting behind a classmate that he calls “Tosha Jones” and being drawn to what he describes as “Two fudge colored cheeks with a sheet of khaki stretched across, their mass squeezing through the chrome reverse “U” in her chair back.” (<i>The Black Body</i>, 161) Jasper goes on to describe what more than a few of us remember as “the feel up,” both entranced by her ass, and perplexed by her lack of recognition of his groping, until—three minutes later—she handed him a note that stated, “you have to stop now. People are looking.” Taking her note into account, “Tosha’s” silence could at once be read as her investment in comporting herself in a way that “good girls” should—“people are looking”—as much as it might have been an articulation of the pleasure she might have derived from Jasper’s touch. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">Dismissing for a moment the compulsory heterosexual socialization that was also taking place in these stories and the easy ways that “feeling up” can cross the line into predatory sexual behavior (as Jennings admits in his own classroom story), the close proximity of pubescent bodies and sexual desires created the context for that time-tested ritual: the school dance. For young Blacks school dances (and cotillions) were a means of introduction to acceptable public forms of affection and sexual desire, that also hung on notions of glamour, sophistication, and, of course, respectability. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">Yet in another public/private iteration, there was also the house party, in which the private intimacy—the kind that might be outlawed if you were a teen living in your parents’ house—literally morphed into the public intimacy of a living room or basement, amongst a relative mass of folk, themselves pursuing all manner of desire and intimacy. One might recall Luther Vandross singing about “Bad Boy” trying to sneak out the house, <i>to the house party</i>, in a song—“Bad Boy/Having a Party”—that was an extended riff on Sam Cooke’s own celebration of the house party. While Vandross, sings, “roll back the rugs everybody, move all the tables and chairs, we gonna have us a goodtime tonight,” there was always that other moment, a later moment, and often the last moment, when the lights got dimmed—the proverbial “blue light in the basement”—and intimacy was crafted in tight spaces, where partners got to feel the contours of each other’s waist, hips, shoulders…and to literally take in the smell of sexual desire and intimacy. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">And of course there’s the music, preferably a side that pushed towards a 5-plus minute mark, which was a challenge in the pre-digital era, when someone actually had to be in charge of changing the record. The genius of Isaac Hayes was his understanding of such dynamics, hence side-two of his classic <i>Hot Buttered Soul</i> (1969), which only features “One Woman” (5:10) and his seminal remake of Jimmy Webb’s “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” which logged in at 18-plus minutes—or more than enough time for a little public foreplay. </span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">And then there’s Marvin Gaye, whose recordings <i>Let’s Get it On</i> (1973) and <i>I Want You</i> (1976) were both recorded as extended suites, in which one could experience the full gamut of sexual intimacy. Though <i>Let’s Get It On</i> is the more remembered of the two recordings, in no small part to Gaye’s deliberate blurring of the sacred and the sexual—“something like sanctified” as he sang—<i>I Want You</i> is a masterpiece of unbridled sexual desire. The album begins with the invocation of desire—“I want you, and I want you to want me too”—touring through tracks such as “Feel All My Love Inside,” “Come Live with Me Angel,” and fittingly closing with the vocal rendition of “After the Dance,” as the dance (with the Ernie Barnes’ original “Sugar Shack” providing visuals) was the original site of desire.</span></span></div><span style="font-size: small;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><span style="font-size: small;"><span style="font-family: Times;">There’s no doubt that the young folk will find their own grooves of intimacy—it just won’t look, sound and feel like the intimacy of my youth. For now, I got a playlist loaded with Marvin, Isaac, a little Al Green, Gloria Scott and Teena Marie’s “Portuguese Lover.”…</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal" style="text-align: justify;"><br /></div>

Published on February 13, 2013 19:16

Marketplace: The Economic Costs of Violence in Chicago

Sylvester Monroe | Marketplace

Last year, Chicago had 506 homicides, the most since 2008. Per capita, that's worse than both New York City and Los Angeles. In January, 42 people were killed, setting a pace that would surpass 2012. In fact, gun violence is actually down across the city overall since the early '90s. But certain neighborhoods on the South and West sides of the city have been decimated by violence -- neighborhoods like Englewood. And it's not just the people who are suffering. The economy of Englewood has also been devastated.

At one time, 63rd Street, a major east-west thoroughfare across the heart of Englewood, was a vibrant economic strip anchored by major department stores like Sears. Today, most major retailers, including the big grocery chains, have abandoned the area. Vacant lots, empty buildings and boarded-up businesses now dot the landscape where thriving enterprises once operated.

It’s not just 63rd Street. The same is true of just about any other commercial street in Englewood and many of the residential areas in the South Side as well. One reason is that Englewood has one of the highest homicide rates in the city. It also has one of the highest unemployment rates. Forty percent of the people who live there are unemployed. And for those who do work in Englewood, dealing with violence has now become part of the job.

Listen HERE

Published on February 13, 2013 09:50

February 12, 2013

Davey D: Legacy of "Police Terrorism" Should Prompt Serious Probe of Christopher Dorner's Claims

Democracy Now

Speaking to Democracy Now!, the Berkeley-based journalist and activist Davey D says that the murder allegations against ex-police officer Christopher Dorner should not deter inquiry into the allegations of corruption and abuse he has leveled against the Los Angeles Police Department. "We should have total transparency when it comes to the police," Davey D says. "And when allegations like this are raised, as journalists — instead of cheerleading which you saw a lot of media do in L.A. — we should be checking it out. [Dorner] named dates, times and places."

Published on February 12, 2013 19:36

Jay Smooth: "Return of the Little Hater (Haters Don't Die, They Multiply)"

illdoc1

Thinking about creative process, and those voices in your head that stop you from getting things done (on the video camera or otherwise). This is a sequel to one of my favorite early Ill Doctrines, "Beating the Little Hater"

Published on February 12, 2013 19:18

The Larry Davis Project (the Life & Death of a Bronx Rebel)

from Shadow & Act :

Larry Davis was a New Yorker who shot six New York City police officers on November 19, 1986, when they raided his sister's Bronx apartment. The police said that the raid was executed in order to question Davis about the killing of four suspected drug dealers. At trial, Davis's defense attorneys claimed that the raid was staged to murder him because of his knowledge of the involvement of corrupt police in the drug business. With the help of family contacts and street friends, he eluded capture for the next 17 days despite a massive manhunt. Davis eventually surrendered to police, and was acquitted of attempted murder charges in the police shootout case, and was acquitted of murder charges in the case involving the slain drug dealers. He was found guilty of weapons possession in the shootout case, acquitted in another murder case and was found guilty in a later murder case and was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

In 2008, Davis was stabbed to death in a fight with another inmate.

The Larry Davis case generated controversy. Many were outraged by his actions and acquittal, but others regarded him as a folk hero for his ability to elude capture in the massive manhunt, for so many years, or as the embodiment of a community's frustration with the police, or as "a symbol of resistance" because " he fought back at a time when African-Americans were being killed by white police officers. "

Based on that true story, The Larry Davis Project gives insight into the motivations of a Bronx youth in the 1980s. At a time of police corruption, drug proliferation and rampant poverty, a young Larry Davis struggled with who he would become - thug or artist?

The feature film, which comes from Epoch Motion Pictures, is scheduled to debut sometime this year.

Published on February 12, 2013 15:53

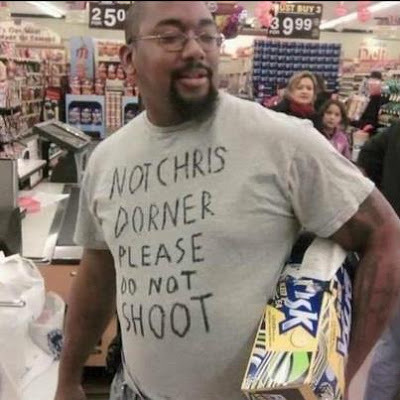

Black Residents to LAPD: "Don’t shoot. I’m not Christopher Dorner"

Published on February 12, 2013 07:54

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.