Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 9

July 13, 2023

Jermaine Fowler on Black horror, “The Blackening” and stand-up | Salon Talks

'Actor and comedian Jermaine Fowler, who calls himself a “horror movie fanatic,” talks to Salon’s D. Watkins about working with the talented cast of Tim Story’s The Blackening— a horror film that seeks to flip the genre on its head. Fowler shares that the cast, which includes Yvonne Orji, Jay Pharoah and Sinqua Walls, were so funny they all needed a code word to remind them to focus. Fowler also names some of his favorite horror movies and shares what it means to see Black horror films like Get Out, Us, and now, The Blackening become breakout successes.'

Issa Rae’s Dramatic Family History Is Like a “Soap Opera” | Finding Your Roots | Ancestry©

'Actress and producer Issa Rae gains clarity on where she comes from… with a surprising twist ending that she likens to a soap opera! Watch as Henry Louis Gates Jr. walks her through her family history on PBS’s Finding Your Roots.'

July 12, 2023

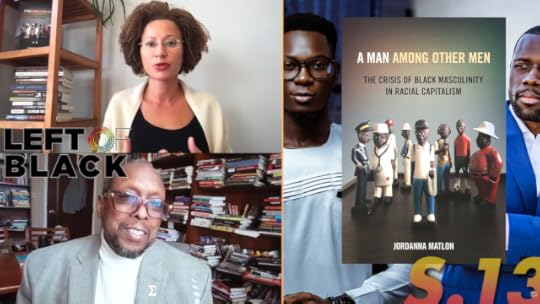

Left of Black S13 · E16 | Dr. Jordanna Matlon on Black Masculinity and Racial Capitalism

What is the lasting impact of Black masculinity being used as a tool of capitalism and commerce? Dr. Jordanna Matlon, Assistant Professor at American University, joins Left of Black host Dr. Mark Anthony Neal to discuss her new book, A Man among Other Men: The Crisis of Black Masculinity in Racial Capitalism (Cornell University Press). Dr. Matlon takes us to the city of Abidjan, located in Côte d'Ivoire (Ivory Coast) to see how this dynamic plays out in the construction of masculinity in this West African nation.

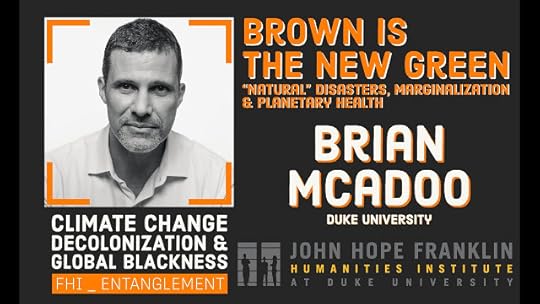

Brown is the New Green: “Natural” Disasters, Marginalization and Planetary Health with Brian McAdoo

'Nature does not cause disasters. A natural hazard can rapidly turn into a disaster when it encounters a community made vulnerable by unjust economic systems, environmental degradation and centuries of systemic racism. In this talk, Brian G. McAdoo, a disaster researcher and head of the PlanetLab in the Earth and Climate Science Division at Duke University's Nicholas School of the Environment, explores the nature of natural disasters by providing a framework in which we can understand the intersections of hazard and vulnerability in order to create more sustainable and just solutions. He explores case studies in Nepal, Haiti and Madagascar.'

Beside Fire Chats | A People's Guide to New Orleans: Precarity and Possibility in Producing Radical Histories of the City

'Drs. Lynnell Thomas and Elizabeth Steeby, co-authors of A People's Guide to New Orleans, discuss what it's like to produce a social justice tour guide to a city so defined by precarity and possibility. We highlight a few of our sites and introduce the work of activist collaborators who will be included in our guide, such as Leon Waters and his Hidden History tour, and jackie summell and her Solitary Gardens project.'

Millennials Are Killing Capitalism: “A Statecraft of Torture” - Orisanmi Burton on the CIA, MKULTRA, New York Prisoners and Indigenous Children

'In this episode of Millennials Are Killing Capitalism, a conversation with Orisanmi Burton about the connections betweenthe Central Intelligence Agency’s MKULTRA program, former GovernorNormal Rockefeller, the Rockefeller Foundation, McGill University,the Allan Memorial Institute and experiments that were conducted inNew York State prisons. Burton is the author of Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt (University of California Press, October, 2023).'

June 18, 2023

Godfather(s) of Harlem: Postmortem by Mark Anthony Neal

Godfather(s) of Harlem: Postmortem

by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (inExile)

Malcolm X is dead. It is perhaps the most anticipatedpredetermined death in the history of television. However fast and loose Godfatherof Harlem, the MGM series about Harlem gangster and Malcolm X confidanteEllsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, played with history, Malcolm X was always going tolay bloodied and shot-gunned riddled on that make-believe Audubon Ballroomstage. And yet I found myself again mourning the always alreadydeath of Malcolm X – as I have in so many film and documentary depictions – butalso mourning the still yet to be determined demise of the central characterBumpy Johnson, who most certainly will also be dead by the end of the 1960s.What I am mourning is not simply the rupture of the thematic center of ahistorical drama – one that had no choice but to jump the proverbial shark –but something more: the (again) closure of the possibilities of improbablerelationships and the unrequited politics attached to them, forged in fiction,innuendo, and in real life that continues to animate, if not haunt, mynostalgia (and others I surmise) for the Black world that could have been, theBlack world that I was born into, so many decades ago.

Truthfully, I wasn’t going to watch another Black “Gangsta”Drama, having given up that ghost almost twenty-years ago when writer DavidSimon couldn’t, or rather wouldn’t, imagine another outcome for The Wire’sStringer Bell, who for me embodied the very improbabilities of possibilitiesfor a so-called Black criminal class. Bell, portrayed with nuanced aplomb byIdris Elba, recalled Lawrence Fishburne channeling an early cinematic renderingof Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson in the film The Cotton Club(1984): “the White man ain’t left me nothing but the underworld, and that iswhere I dance.” (Fishburne reprised his depiction of Johnson in the 1997 film Hoodlum.)In Simon’s mind Bell “had to die” to serve the series.

If Stringer Bell’s appeal to me twenty years ago resided inthe Black Nationalist inspired belief that every thug, mercenary, rapper, andself-styled entrepreneur could be rehabilitated in the name of Black “progress”(however the needle moves), it was a move whose initial appeal for me wasalways the Malcolm X that I “met” forty years ago. As a 19-year-oldcollege student, I was under the sway of the Nation of Islam, which was magicaland revelatory for so many of us in the mid-1980s, and it was in that contextthat I first deliberately imbibed Malcolm. In my own misguided pursuit ofBlack masculine perfection – in my colored-Lee jeans, pastel colored-socks,Jersey-fade, oxford-button downs, argyle sweaters and fake-leatherpenny-loafers with real pennies (I just bought my first pair of Bass Weejuns ayear-ago), Malcolm had a powerful charm.

Larry Neal famously wrote, “I am at the center of a swirlof events” in a poem that he titled “Malcolm X: An Autobiography” as Neal takesnot the first, and certainly not the last, liberty with the meaning of a manwho, as that foundational line suggest, would never be fully contained by metaphor,ideology, and history. Malcolm seemed to be always imbued with desire andpromise, the latter practically guaranteed by his premature death. The ideathat Malcolm X was always more “work-in-progress” than finished product servedthe needs of my younger self. Surely, I was not the first to be taken by theseeming malleability of the idea of Malcolm, which seemed, even when presentedfrom rigid Black Muslim or Black Nationalist lens, more accessible than that ofMartin Luther King, Jr. – the two long accepted as the Alpha and Omega of anidealized political Black masculinity.

When Ossie Davis invoked Malcolm X as our “Black ShiningPrince” on the occasion of his first death – the death of Malcolm tobecome metaphor and spectacle for generations to come – it concretized the ideaof Malcolm X as an idealized manifestation of our collective desires for theperfect patriarch for our imperfect politics. But we’ve learned enoughabout so many of our Black Shining Princes, that our idealized desires only embodiedour own collective imperfections, as they should; these princes were always ofus and from us, not beyond us. Even the Good Reverend Doctor, who for a timestood as the moral authority for a Nation – until he wasn’t – possessed foibleswhich our failure to admit, if we are honest, has made it easier for hispolitical appropriation by forces who have only had use for him because he isdead, and his legacy distorted. If Malcolm felt purer to me as a 19-year-old,and certainly as an adult who is nearly 20 years older than Malcolm was when hefirst died, it was because Malcolm always felt more honest, or dare Isay real.

There is often talk, particularly every January of thecalendar year, of the sanitized King who gets paraded to sell us tickets to fundraising“Prayer Breakfasts” and presents us with 20%-off sales at your favoritesoon-out-business box store. But the Malcolm X that lives in our collectivememory is no less sanitized, frozen in that decade or so after his parole in1952 and his break with Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam in 1964. Thisnot to say that this Malcolm is caricature, but this sense of him operates onthe belief that this Malcolm most matters because he was redeemed – by theHonorable Elijah Muhammad, for sure – but also by a higher calling of Blackliberation, which Malcolm Little (in his various iterations) hopelesslyundermined, if unconsciously.

The Malcolm X that we meet in the Harlem-world of MGM’s Godfatherof Harlem functions as the straight man, and often moral compass, to the“gangster” Bumpy Johnson, who finds a willing accomplice in Forest Whitaker’sbrooding, introspective performance. And straight man is not too on the nosedescription of Nigél Thatch’s overly serious and carefully curated Malcolm(Thatch also portrayed him in Ava Duvernay’s Selma), who lacks theorganic sense of humor and comedic timing, that made Malcolm alluring to somany Black Americans; Malcolm X and Dick Gregory could have toured as the Kingsof Comedy in the early 1960s. This is not to say that Thatch’sperformance is anything less than elite, so much so that Malcolm is essentiallya walking corpse in Season three of the series when Thatch was replaced becauseof scheduling conflicts.

That Malcolm X is forced into a supporting role, as isGiancarlo Esposito’s kitschy Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., speaksvolumes about the series’ investment in Bumpy Johnson. In the Harlemyears of 1963-1965 as depicted in Godfather of Harlem, Bumpy Johnson, asopposed to Malcolm X, to again recall Larry Neal, is the “center of aswirl of events.” This is, in part, the by-product of Whitaker’s performance,as Lorraine Ali observes, “Whitaker’s phenomenal as the out-of-touch godfatherwho’s playing catchup in a new world and plays his character with a quiet yethaunting nuance that is this actor’s specialty.” (Los Angeles Times,2019) The series covers the March on Washington in 1963 (where Powell andMalcolm X are said to have traveled to together, not as participants, but asobservers), the rise of Muhammad Ali (who makes several appearances), TheHarlem Riot of 1964, and incredulously, the failed attempt by the New York Citymob and the CIA to assassinate Fidel Castro when he spoke at the United Nationsin the fall of 1964.

Perhaps expectedly for a “mainstream” cable network, thelabyrinth of relationships between the Brother Minister, the Congressman andthe Gangster are overshadowed by Bumpy Johnson’s relationship with the New YorkCity mob. This is particularly unfortunate given the secondary role of theBlack women of Godfather of Harlem, like Betty Shabazz (portrayedby the lovely Grace Porter), Bumpy’s daughter Elise Johnson (AntoinetteCrowe-Legacy), who is transformed from drug addict to devout Muslimduring the series’ run, and Ilfenesh Hadera, who thrills as Bumpy’s wife MaymeJohnson, a performance that reminds that many fine “Negro” women were a triggerhair away from a “wig snatch” and the use of that razor in her bra.

It is the relationship between Bumpy and Vincent Gigante,played with alarming sophistication by Vincent D’Onofrio that takes up way toomuch space in Godfather of Harlem. As a historical period piece,neophyte viewers are more likely to google New York City’s major crimefamilies, while watching Godfather of Harlem, than the Nation ofIslam. Indeed, watching D’Onofrio as Gigante, Chazz Palminteri as FrankBonnano and the late Paul Sorvino’s Frank Costello, you could well be watchingA Bronx Tale, Goodfellas, or The Firm, given Sorvino’s roleas a taciturn mobster in that film. At times Bumpy Johnson’s Harlem simplyfeels like a backdrop to another mafioso drama with attendant collateralnarrative damage, which mirrors the historical collateral violence associatedwith the complex financial relationship between Black Harlem and The Mob.

It was in the context of that violence that Bumpy Johnsonfirst earned his reputation in the 1930s as an enforcer for Harlem numbersrunner Stephanie St. Claire, as she navigated a mob war between Lucky Lucianoand Dutch Schultz (the subject of the film Hoodlum). As Francis A.J.Ianni writes in the book Black Mafia: Ethnic Succession in Organized Crime(1974), “Johnson worked essentially as a middleman for the Italiansyndicate…Italian racketeers knew him as a ‘persuader’, one who could settleunderworld quarrels before disputes erupted into violence.” (119) Simply,Johnson was the most prominent Black emissary between Black Harlem and the fivecrime families. While that might have been the case in terms of organizationalstructure, Johnson’s widow Mayme Hatcher Johnson assures in her book HarlemGodfather: The Rap on my Husband, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, that he wasthe “undisputed King of the Harlem Underworld.” (14)

Though the spectacle of New York’s so-called “Five CrimeFamilies'' and their interests in the illicit economy of Black Harlem is one ofthe reasons why a series like Godfather of Harlem was greenlit,the full scope of the series reveals the contradictions that were BumpyJohnson, and inevitably those of so many working-class and poor Black menseeking a way “up and out” with limited skills, education, and a lack of accessto real and sustainable financial resources. Those contradictions are as muchbaked into the aspirational politics of Black America in the post-World War IIperiod, as they were in the lives of the men, who for so long came to defineand represent those politics. Though he is rarely considered in the accountingof the losses that marked this transitional and transformational period inBlack American life, Bumpy Johnson warrants the attention that Godfather ofHarlem lavishes on his legacy.

For the late Paul Eckstein, who was the co-creator of Godfatherof Harlem with Chris Brancato, who also wrote the screenplay for Hoodlum(which Eckstein co-produced), Johnson’s complicated legacy was personal:Johnson helped Eckstein’s grandmother pay for college. While the gangster witha heart of gold is a timeless trope, even as a performative gesture – thinkinghere of Wesley Snipes’ Nino Brown handing out turkey dinners in New JackCity – such gestures mattered in Black Harlem where any recognition of Blackhumanity could curry respect. Harlem was a place and space where at times therewas little distinction between ghetto celebrity, race men and women, and Blackfamous entertainers and athletes.

For every eyebrow that Bumpy Johnson’s close, if contentious,relationship with the mob raises, it is his relationship with Malcolm X thatregisters as most surprising. Godfather of Harlem captures the duocommiserating over meals, coffee, and games of chess. From a narrativestandpoint, those moments where Bumpy is featured with Malcolm servesEckstein’s desire to make “sure these characters are gray and morally on apath”, but how real was their relationship? (Variety). The young Malcolm Little was certainly aware of the reputation of Bumpy Johnsonwhen he was in Harlem in the 1940s, and perhaps Johnson might have heard of thepetty criminal “Detroit Red”, if only because of his 6’ 4” frame and flamingred hair. Johnson was incarcerated when Malcolm X returned to Harlem to run theNation of Islam’s Mosque No. 7, after his own prison stint, and the Harlem thatJohnson confronted when he returned from prison in 1963 was in many ways, nowMalcolm’s Harlem. Malcolm X may have broken bread and laid his head inEast Elmsford, NY with his family, but Harlem was always his home.

Mayme Johnson writes that Bumpy and Malcolm really didn’t connect until 1963,and largely in the context of ridding Harlem of the narcotics traffic that wasat the center of Johnson’s contradictions. Even as Mayme Johnson describes herhusband as “A scholar and a thug”, the fact is that such a description was alsoin the DNA of Malcolm – he never lost that ability to move through those ghettostreets – that made the two men foils for their worldviews about Blackprogress. In Harlem Godfather, Mayme Johnson writes, “Bumpy wasimpressed with Malcolm, and [he was] one of those who supported Malcolm’s neworganization after he left the Nation of Islam in 1964.” Mayme Johnsonalso confirms Bumpy’s offer to provide protection for Malcolm X and his familyin their East Elmsford home, a storyline that is presented as a dramaticfracture in their relationship. “I offered him protection and he turned itdown”, Mayme Johnson recalls her husband telling his associate Jamison"Junie" Byrd, adding he “said he didn’t want men with guns around himbecause it would be like he was trying to provoke something. He shouldalistened to me.” (Harlem Godfather, 210)

In her memoir, Mayme Johnson suggests that her husband’ssupport for militancy and Black radical politics was not limited to hisfriendship with Malcolm X. “Bumpy especially had a soft spot for theBlack Militants who were just making the scene in Harlem”, Mayme Johnson writesin Harlem Godfather, specifically citing the then Leroi Jones (AmiriBaraka) who she says her husband “would talk from time-to-time.” (210). Mayme Johnsonalso name drops H. Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, and Max Stanford, one of thefounders of the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), among those that BumpyJohnson “knew and supported.”

This lesser-known aspect of Bumpy Johnson’s legacy isperhaps the reason why, when journalist William Gardner Smith, working as acorrespondent for the French News Agency (Agence France-Presse), began tocompile the essays that would make up his collection Return to Black America,Johnson was one of the figures that he talked with. Smith was among ageneration of well-known and not-so-well-known Black American expatriates inFrance, of which his inner circle included fellow novelist Chester Himes andeditorial cartoonist Ollie Harrington. Smith's most well-known work is thenovel The Stone Face (1963), inspired by his witnessing of the treatmentof Algerians in Paris during the midst of the Algerian War. As Adam Shatzwrites, “The Stone Face explores a black exile’s discovery of aninjustice perpetrated by his host country, a place the protagonist, SimeonBrown, a young black American journalist and painter, initially mistakes forparadise.” (New Yorker, 2019)

It was Bumpy Johnson’s similarity to Algerian rebel Ali LaPointe, who started out as a criminal in the casbah, that inspired Smith’sdecision to talk with Johnson when he returned to the United States in 1967 and1968 to report on the Black Liberation Movement. La Pointe is one of thesubjects of the 1966 film, The Battle of Algiers. In addition toJohnson, Smith spoke with Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, the honorableElijah Muhamad, and Black elites, one of whom admitted to Smith that“Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown and all those other noisy niggers get onmy fucking nerves!” (Return to America, 23). It goes without saying thatsome members of the Black elite were just as disgusted with Black radicals, asthey were with career criminals like Bumpy Johnson.

In Return to America, Smith recalls a situationduring the summer of the 1967, when members of the Congress of Race Equality(CORE) began to picket a local police precinct in New York City’s GreenwichVillage neighborhood – the site of the Stonewall Riots two summers later – overincidents of police brutality. Working in collusion with the New YorkCity Police Department, members of the New York Mafia, as Smith reports,threatened to violently disperse the protesters. According to rumor, or legendas things had become in relation to Johnson, he sent a simple message: “If anyof those CORE kids are harmed, I will not guarantee the safety of any Mafiamember in Harlem.” (Return to America, 26). When Smith pressedJohnson on this incident or any number of Apocryphal stories about him,including one claim that he helped rescue Paul Robeson from a racist mob inPeekskill in 1949, he simply responded “Because what I am really, when thechips are down, is a black nationalist.”

At the time of Smith’s interview with Johnson, theso-called Gangster was in his mid-60s. Born in 1906, Johnson was closer in ageto Civil Rights leaders A. Phillip Randolph (born in 1889) and NAACP leader RoyWilkins, who was four years older than Johnson. That the “balding, softspoken”Johnson broke ideological ranks with an older guard of Black leadership was assignificant as his fundamental belief that his vocation was an attempt at Blackprogress. In the spirit of the distinctly Black American adage of “making a wayout of no way”, Bumpy Johnson summoned his social capital and streetwiseingenuity to imagine another way out. Whitaker, who may be at his bestliving as Johnson, feels “like Bumpy has all the potential in the world but isbeing denied [opportunities to realize it], adding that Godfather of Harlem“talks about the opportunities that we have and have not and what this one mandid to achieve them and really looks at if it’s ethically right.”(Ebony) That Johnsonhas been lost to historical obscurity has much to do with our own collectivediscomfort with the collateral damage of Black progress, be it Johnson’scriminal enterprise or those who advocated armed struggle in the 1960s.

On July 7, 1968, a month after the assassination of SenatorRobert Kennedy and three months after the assassination of Martin Luther King,Jr. – still regarded more than fifty-years later as pillars of Black mainstreampossibility – Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson died, not in a fiery shootout with theMafia, but over a plate of fried chicken in a Harlem eatery.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African & African American Studies, Professor of English, and Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. Neal is the author of six books including the just published Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive (2022), What the Music Said: Black Popular Music and Public Culture (1999), Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture, the Post-Soul Aesthetic (2002) and Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities (2013), and co-editor, with Murray Forman, of That’s The Joint!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader (now in its 2nd edition).

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-font-kerning:1.0pt; mso-ligatures:standardcontextual;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

April 18, 2023

WRITING HOME | s3, e3, “boundaries” | Gina Athena Ulysse

“You don’t really know a boundary until you’ve pushed against it.” – Gina Athena Ulysse

'Trouble-making wonder Gina Athena Ulysse gives Kaiama and Tami a glimpse into the boundless whirl of her creative (and) scholarly practices.'

A long way from the block | "There's a voice for us"— a conversation with jazz vocalist Dwight Trible

'Origins and influences are featured in this episode's conversation with Dwight Trible, including his love and appreciation for jazz drummer extraordinaire Brian Blade and his collaboration with the great Kenny Garrett, whose album "Sounds from the Ancestors" he played on. He describes his early life in Cincinnati, before he moved to Los Angeles, and some of the racial issues he encountered as a young boy. We talk about what it was like for him to work with Leimert Park elders and legends like Billy Higgins, Art Davis, Horace Tapscott, and Kamau Daáood. We discuss The World Stage, founded by Daáood and Higgins, and its importance as a grassroots, community-owned cultural center for progressive music. Content and the sacred are important themes throughout.'

Every Voice with Terrance McKnight | The Magic Flute: From Morehouse … to the opera house with Monostatos

'The Moorish character Monostatos in Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” is one of the most famous representations of Blackness in opera - a genre with limited representation of characters of African descent. But many are interrogating the Black caricatures that European classical music long ago crafted and continue to cultivate to this day. In the debut episode of Every Voice with Terrance McKnight, we meet Dr. Sharon Willis, Dr. Uzee Brown, and others who are lifting the mask behind opera’s representation of marginalized voices to create something more inclusive and more beautiful for all of us.'

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers