Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 884

July 10, 2013

ReelBlack: 'Fruitvale Station' Director Ryan Coogler Discusses the Current State of Black Film

ReelBlack

Ryan Coogler, writer/director of the award-winning FRUITVALE STATION discusses the current state of African-American film in this excerpt from the forthcoming feature documentary, BLACK FILM NOW. Make a donation to the project. email filmmaker Michael Dennis at info@reelblack.com for details. Camera Craig Carpenter and Phillip Todd. A Reelblack exclusive.

Published on July 10, 2013 04:31

July 9, 2013

The Fosters: J-Lo's Positive Portrayal of Foster Care Families by Lee D. Baker & Sabrina L. Thomas

The Fosters: J-Lo’s Positive Portrayal of Foster Care Families

by Lee D. Baker & Sabrina L. Thomas | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The Fosters: J-Lo’s Positive Portrayal of Foster Care Families

by Lee D. Baker & Sabrina L. Thomas | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Whether it isLaw and Order, Grey’s Anatomy, some old action movie on TNT, or a sappy flick on the Lifetime Movie Network, a version of this scene is repeated over and over and serves as a powerful framing narrative through which many people come to understand foster care. The actual family who provides care, love, and nurturing to that vulnerable little girl is invisible.

There is a new television series on ABC Family, aptly titled The Fosters, that provides a complex, nuanced, and creative approach for depicting the joys and challenges of foster families. Super-star Jennifer Lopez is the show’s Executive Producer, and her creative genius and commitment to depicting blended families in a positive light shines through brightly. Her insightful understanding of how race, class, and gender clash and collide in unsuspecting ways provides a powerful subtext for the compelling stories of this newfangled TV family.

Writers Peter Paige and Bradley Bredeweg have assembled a dizzying array of endearing characters to depict this modern extended family. Set in the Mission Bay area of San Diego, parents Lena Adams (Sherri Saum) and Stef Foster (Teri Polo) serve as a vice principal at a charter school and a tough but kind police officer, respectively. When Lena, a black woman, and Stef, a white woman, married, they agreed to raise Stef’s biological son and foster infant twins Jesus (Jake T. Austin) and Marianna (Cierra Ramirez), who they eventually adopt. The show ensues once the children all reach their teenage years and another teen is added to the mix, 16-year old Callie Jacob (Maia Mitchell) who is sweet and caring, but has an edge sharpened on the anvil of abuse and neglect.

Although the houseful of teens are into sports and music, and the regular drama of teenage angst, relationships, and experimentation, the show deals with the consequences of unprotected sex, stealing another sibling’s ADHD medication to sell as drugs, and the tension that arises when one of your friends has a crush on your brother. Add to this the issue of kids still loving birth parents who are abusive and also loving siblings who are being abused by those parents, there emerges a different kind of dimension and dynamic to TV family dramas, with an emphasis on drama.

While some may feel that this show pushes the envelope in terms of race, same-sex relationships, and teenagers navigating sex, mature relationships, and drugs, one must remember it is an ABC Family drama and not a racy HBO show. Its real premise is a display of strong family values and loving parents married like any other couple.

Perhaps most importantly, this is a great show that depicts how foster families can have a positive impact on children as they grow into adults. Foster parents finally have a constructive image to combat that crying eight-year-old holding perilously to her mother’s hips, before she is whisked off to some nameless and faceless family “in the system.”

What we like most and appreciate about The Fosters is that it depicts foster kids within a family, not a system.

***

Lee D. Baker is Professor of Cultural Anthropology and Dean of Academic Affairs of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences at Duke University

Sabrina L. Thomas is Associate Dean of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences at Duke University. They are married and provide foster care for children.

Published on July 09, 2013 16:26

#MoralMonday: "Unpacking the Regressive Language"—Rev. Dr. William J. Barber, II

Moral Monday

July 8th, 2013 - During the 10th Wave Moral Monday rally at the North Carolina General Assembly, Rev. Dr. William J. Barber, II unpacks the language that is used to pass regressive legislation.

Published on July 09, 2013 16:05

Profiling Trayvon...Again by David J. Leonard

The "Angry Trayvon" App

Profiling Trayvon…Again

by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

The "Angry Trayvon" App

Profiling Trayvon…Again

by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Watching the George Zimmerman trial has been a daily reminder of the ways that race and the criminal (in)justice system collide. The trial has been a daily display of the different standards, scripts, and narratives afforded to both victims and the accused, and how race sits at the center of these “two Americas.” Media coverage of the trial has presented judgments on whose life matters, whose future matters, whose pain matters, whose suffering matters, whose experiences matter, and who deserves, is entitled to, and will receive sympathy, mourning, and justice.

Just as every person within America is profiled as guilty or innocent, as desirable or undesirable, violence is profiled as well. Gun violence is profiled racially. Victims are profiled racially. Perpetrators of violence are profiled; the families and friends are profiled as well; communities are not spared from this process. Ultimately, the narratives embraced are dissimilar across communities whereupon race creates a dividing line that marks them as separate and unequal. This is racism at its core.

“Deep in the white American psyche” rests the controlling belief that sees “the impossibility of Black innocence” (Mann 2013). Inside this same dominant worldview is that impossibility of white guilt.

The perpetual criminalization of Trayvon Martin is telling; the efforts to blame him for his own death; whether from the defense questioning of Sabrina Fulton or the mentions of trace amounts of THC in his system at the time of his death, are evident in the ubiquity of depicting Trayvon as a “thug,” a “suspect” and a “criminal” (a CNN “expert” even justified Zimmerman’s profanity-laced 911 call because he thought he was following a criminal).

All of this is operates from and perpetuates the presumed guilt of Trayvon Martin and black bodies in general. Zimmerman, on the other hand, is presumed innocent and a good person who is now being victimized.

On Fox News recently, Greg Jarrett and Kimberly Guilfoyle lamented the costs and anguish experienced by Zimmerman, citing his weight gain as evidence of his victimization. “You eat when you’re under stress and pressure and stuff like that,” Guilfoyle reminded the audience, “So, you know, he’s already been punished to some extent. We’ll wait and see whether a Jury punishes him further.” “This is an individual that was trying to do some civic duty by being on the community watch,” Jarrett noted, “that was the purpose of why he was there that night.” In other words, Zimmerman was a victim; victimized in the past, on this fateful night, and through the process. Sympathizes should rest with him.

While the verdict has not been read, the trial itself, the media coverage of the trial, the focus on the Newtown shootings as opposed to gun violence in Chicago, as well as the demands for background checks and not jobs, and the focus on mental health and not schools, are testaments to the ways race sits at the center of discourses of gun violence, and the criminal justice system.

Black death and white death are conceived as separate and unequal within the dominant white imagination; yet the stories about life and death in black and white are contingent upon one another. White life is privileged over anything else.

The scripts we see with regards to Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman, or Newtown, and Chicago, are the stories of guilt and innocence; they are the stories of blacks and whites—evidence of the persistence of racism and the illusion of post-rTo look at the stories told of Adam Lanza and James Holmes is to look at the difference in the profiling of and narratives associated with Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis, another unarmed black teen shot to death in Florida. W.E.B Dubois once asked when writing about America’s race question, “how does it feel to be a problem?” Contemporary discussions of gun violence, from inner-cities to the suburbs, highlight the continued relevance of his words within America.

While the judge limited the ability of the prosecution to bring race into focus and to talk about racial profiling, among other things, race remains at the center of the trial and the criminal justice system—at the heart of life and death. The demands for colorblindness amid the realities of a racist America means that this trial, like those before, are playing out according to the hegemonic script: black criminalization and white innocence. It is my hope for a new ending where justice and mourning no longer remain a dream deferred.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. Leonard’s latest books include After Artest: Race and the Assault on Blackness (SUNY Press) and African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (Praeger Press) co-edited with Lisa Guerrero. He is currently working on a book Presumed Innocence: White Mass Shooters in the Era of Trayvon about gun violence in America.

Published on July 09, 2013 06:44

July 8, 2013

The Genesis: Gentrification in Harlem w/ Vinny Cha$e

Life+Times

Harlem rapper Vinny Cha$e and his Cheers Club crew take us through their stomping grounds to survey both the positive and negative impacts of increasing gentrification on the legendary New York city community.

Published on July 08, 2013 11:14

July 7, 2013

Ira Tucker & Jay Z Sharing a Ride in a Chrysler 300: The Legacy of Bobby 'Blue' Bland by Mark Anthony Neal

Ira Tucker & Jay Z Sharing a Ride in a Chrysler 300: The Legacy of Bobby “Blue” Bland

by Mark Anthony Neal |

NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Ira Tucker & Jay Z Sharing a Ride in a Chrysler 300: The Legacy of Bobby “Blue” Bland

by Mark Anthony Neal |

NewBlackMan (in Exile)

I imagine that Shawn Carter and Ira Tucker never met. That the late lead singer of one of the most heralded Gospel groups might have ever had reason to share an automobile ride with Hip-Hop’s most celebrated mogul, seems surreal. Yet there are three minutes of music, recorded in 2001, and produced by Kanye West, and later sampled as part of an ad campaign for the Chrysler 300, that suggest that such meeting was entirely plausible—at least digitally. The driver of that automobile would have been Bobby “Blue” Bland, the legendary Blues and Soul singer, who died recently at age 83.

Mr. Tucker was one of the early and most important vocal influences on Bobby “Blue” Bland. Mr. Carter’s “Heart of the City (Ain’t No Love”) is a sonic reconstruction of Bobby “Blue” Bland’s 1974 classic “Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City.” That Mr. Bland’s artistic influence could bridge the gap between a Gospel group founded in 1928 – Mr. Tucker, who died in 2008, joined the group 1938—and a former drug-dealer-turned-rapper-turned high-end urban tastemaker, speaks volumes about the legacy of an artist that rarely got his deserved recognition. Quite simply: Bobby “Blue” Bland was one of the most distinct and accomplished voices of the 20thCentury.

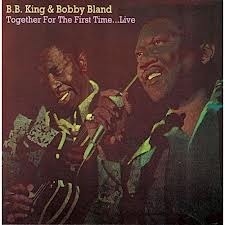

Mr. Bland was a singer that for Black men of a certain age, he was a singer of choice for their fathers, when they were Black men of a certain age. My own introduction to Mr. Bland came in the mid-1970s as my father regularly listened to Mr. Bland’s two live duet albums with B.B. King, Together for the First Time (1974) and Together Again…Live (1976), on Sunday afternoons (his day off), usually with some brown liquor in close proximity. Mr. Bland with his Tennessee (by way of Memphis) drawl provided a sonic connection for my dad to his Southern roots as he toiled up north in the Bronx and Brooklyn—or what scholar and critic Farah Jasmine Griffin refers to as “South in the City” in her classic text Who Set You Flowin’?: the African American Migration Narrative (Oxford Press, 1996).

With songs like “I Like to Live the Life” (originally recorded by Mr. King) and “That’s the Way Love Is” (originally recorded by Mr. Bland) tucked away in my cultural memory—and later my record collection when I jacked the albums from my father—Mr. Bland didn’t pique my interest again until the mid-1990s when his music showed up in films such as Eve’s Bayou (1997) and Jason’s Lyric(1994), where D. R. S.—Dirty Rotten Scoundrels—of “Gangsta Lean” fame, sample Mr. Bland on the track called “No More Love.” Before Mr. Bland became an answer in the “where did Kanye get this sample from quiz, “ he had established himself—over the span of fifty-plus year career—as one of the last great links to the early moments of the Soul era.

With songs like “I Like to Live the Life” (originally recorded by Mr. King) and “That’s the Way Love Is” (originally recorded by Mr. Bland) tucked away in my cultural memory—and later my record collection when I jacked the albums from my father—Mr. Bland didn’t pique my interest again until the mid-1990s when his music showed up in films such as Eve’s Bayou (1997) and Jason’s Lyric(1994), where D. R. S.—Dirty Rotten Scoundrels—of “Gangsta Lean” fame, sample Mr. Bland on the track called “No More Love.” Before Mr. Bland became an answer in the “where did Kanye get this sample from quiz, “ he had established himself—over the span of fifty-plus year career—as one of the last great links to the early moments of the Soul era.Yet to describe Mr. Bland as a Soul singer is perhaps confounding for an artist who began his career on Beale Street in Memphis in 1949 alongside the likes of Rufus Thomas (later to become the Godfather of the Stax label), Little Junior Parker (later immortalized as “a cousin of mine” on Al Green’s “Take Me to the River”), and the man who would become his lifelong friend, the aforementioned Mr. King; Soul music a we now understand it was still a concept yet to be worked out in Ray Charles’ imagination.

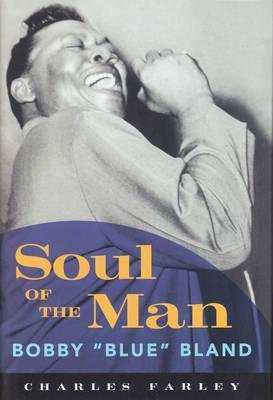

Yet the melding of the rhythms of Rhythm and Blues and the Gospel chords and harmonies that helped create the sound that would literally transform the nation less than a generation after Mr. Bland began his career were always already on his mind. Mr. Bland grew up listening to groups like the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Pilgrim Travelers. In his teens Mr. Bland was part of a Gospel group called the Miniatures that were patterned on the Pilgrim Travelers. As Mr. Bland told Living Bluesmagazine (quoted in Charles Farley’s recent biography Soul of the Man: Bobby “Blue’ Bland ), “I love to sing, always, and I find myself doing rhythm and blues, rock ‘n’ roll, what have you, but I still have the spirituals in the all the tunes that I do.” Even Jay Z recognized this spiritual dynamic, prefacing the bridge of “Ain’t No Love (Heart of the City)”—where Mr. Bland’s vocals appear in their clearest—with the quip, “Take ‘em to Church.”

Mr. Bland would need that spiritual grounding, coming of age in the world of early R &B or what James “Thunder” Early (Eddie Murphy) describes as “rough and Black” in the film version of Dreamgirls. As fate would have it, Mr. Bland would eventually land at the Black owned Duke/Peacock label family, where his career would be tethered for two decades to legendary record label owner Don Robey. If the recording industry was the grand hustle in the post-World War II period for many immigrant communities—the Chess Brothers (Chess Records) and Ertegun Brothers (Atlantic Records) being prime examples—it was even more so for Black hustlers with their tentacles already lodged into the illicit and unregulated world of the Chitlin’ Circuit.

Mr. Bland would need that spiritual grounding, coming of age in the world of early R &B or what James “Thunder” Early (Eddie Murphy) describes as “rough and Black” in the film version of Dreamgirls. As fate would have it, Mr. Bland would eventually land at the Black owned Duke/Peacock label family, where his career would be tethered for two decades to legendary record label owner Don Robey. If the recording industry was the grand hustle in the post-World War II period for many immigrant communities—the Chess Brothers (Chess Records) and Ertegun Brothers (Atlantic Records) being prime examples—it was even more so for Black hustlers with their tentacles already lodged into the illicit and unregulated world of the Chitlin’ Circuit.For a figure like Robey, who served as a role model for Berry Gordy’s fledgling Motown records in the late 1950s and, who was rumored to be the inspiration for the ruthless “Big Red” character in the film The Five Heartbeats (1991), the record industry was an opportunity for mainstream respectability. As Farley notes in his biography of Bland, Robey often negotiated with a .45 on his desk—Shug Knight was a cartoon character compared to Robey—but he understood and valued top-shelf talent. At their peak Robey’s labels boasted acts like Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Memphis Slim, The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Mighty Clouds of Joy, The Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, Johnny Ace, Big Mama Thornton, O.V. Wright, and of course, Mr. Bland.

In the early days, Rhythm and Blues was driven by singles and Mr. Bland released a series of them between 1952 and 1957 for Duke, while traveling the Chitlin’ Circuit with Little Junior Parker. Mr. Bland finally found a hit—in a major way—in 1957 with “Farther Up the Road,” which topped the R&B charts and was a top-50 pop hit. “Father up the Road” benefitted from the shift that was taking place in pop music as Rock ‘n’ Roll and Rhythm and Blues began to dominate the charts and airwaves. 1957, for example, marked the beginning of Sam Cooke’s crossover success, as he achieved his only number-one pop hit that year with “You Send Me.”

While Cooke would go on to a career of crossover success before his murder in late 1964, Mr. Bland would never find that kind of success. Instead Mr. Bland would boast a career of nearly forty top-40 R&B hits between 1957’s “Father up the Road” and 1978’s “Love to See You Smile” becoming one of the most beloved artists for multiple generations of Black audiences. In Soul of the Man, Farley suggest that the reasons for Mr. Bland’s failure to crossover, “was not his style or his brand of the blues, but instead his lack of adequate promotion to the wider record-buying public.” (193) There is some truth to Farley’s observation; perhaps Berry Gordy’s greatest success in crossing-over Motown in the masses was his mastery of the promotional game, including his dogged refusal to label his music “Black music.”

Mr. Bland was clear-eyed about the reasons why he never really crossed-over. As Mr. Bland told Jet Magazine in a 1977 interview, and at a time when he had the backing of a major label in ABC-Dunhill, “They only let one Black at a time get to the top…A Black man still has to do twice what the white man does [to be recognized in the business] You got to turn flips or hang off the rafters.” (quoted in Soul of the Man, 194)

It is also important to note that Mr. Bland also did not look the part of the Black crossover act. Music aside, when you consider the Black male singers who able to sustain some level of cross-over success in the 1950s and 1960s—Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, Little Richard, Ray Charles, Marvin Gaye, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis, Jr. Wilson Pickett, even James Brown to name a few—all possessed the kind of visual quality that might be viewed as attractive, even as some might be described as possessing unconventional good looks.

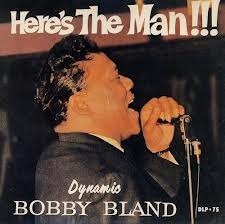

Nevertheless, Mr. Bland stayed on the grind producing s series of signature tunes like “I Pity the Fool” (1960) which was his second number-one R&B song (he performed it on American Bandstand) and was later covered by the Mannish Boys in 1965 (featuring a young David Bowie). A year later Mr. Bland again reached the pop charts (# 28) with “Turn on Your Love Light” which was featured on his 1962 album Here’s the Man. The song would be later covered by The Rascals, Bob Seger, Jerry Lee Lewis, Edgar Winter, and The Grateful Dead, who often featured it in concert.

A signature feature of “Turn on Your Love Light” is a fiery-drum break midway through the song courtesy of Jabo Starks, most well known as one of James Brown’s tandem of drummers (along with Clyde Stubblefield) in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Starks recalls to Mr. Bland’s biographer Charles Farley how he drew from his experience in the “Holiness” or sanctified church: “In the holiness churches, they didn’t have a set of drums, maybe just a snare drum or a bass drum, but they had tambourines, and they clapped. And the way they clapped, I just loved that feel. It’s just a floating feel. They’d clap their rhythm against the songs they were doing—kind of a polyrhythm…that’s basically where it comes from for me. That sanctified rhythm influenced my playing.” (111). Mr. Brown, already a major star in his own right, apparently took note, shortly thereafter hiring Mr. Starks for his own band.

Mr. Bland’s Here’s the Man, also contained a four-minute version of T-Bone Walker’s “Stormy Monday Blues.” Though the song is somewhat of an outlier among Mr. Bland’s output in the 1960s, it was a precursor to the more traditional Blues style he would embrace when he rebranded himself—Jheri-curl and all—in the 1980s. Released as a single in 1963, “Stormy Monday Blues” was followed up by “That’s the Way Love Is” which was backed by “Call on Me” which both became top-Pop-40 hits for Mr. Bland as the lead singles from his 1963 album Call on Me—That’s the Way Love is. “Call on Me ” is a dead ringer for Sam Cooke’s “Everybody Loves to Cha, Cha, Cha.”

Tracks like “That’s the Way Love is” and its doppelganger “Ain’t Nothing You Can Do,” which became Mr. Bland’s highest charting pop song (# 20) in 1964 were written by “Deadric Malone”—a pseudonym created by Don Robey, to essentially deny the actual songwriters their royalties. Berry Gordy used a similar strategy during the rise of the Jackson Five, as many of their early songs were attributed to “The Corporation,” though they were actually written by Deke Richards, Freddie Perren, Fonce Mizell with occasional contributions from Gordy.

Tracks like “That’s the Way Love is” and its doppelganger “Ain’t Nothing You Can Do,” which became Mr. Bland’s highest charting pop song (# 20) in 1964 were written by “Deadric Malone”—a pseudonym created by Don Robey, to essentially deny the actual songwriters their royalties. Berry Gordy used a similar strategy during the rise of the Jackson Five, as many of their early songs were attributed to “The Corporation,” though they were actually written by Deke Richards, Freddie Perren, Fonce Mizell with occasional contributions from Gordy.One notable exception in this era is Bland’s recording of “Share Your Love with Me,” (later recorded by Aretha Franklin) which legendary songwriter Dan Penn, cites as his favorite Bland recording. From his perch at Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Penn, a White songwriter from Alabama, was responsible for classics such as Aretha Franklin’s “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man,” James and Bobby Purify’s “I’m Your Puppet,” and James Carr’s “Dark End of the Street.” As Penn told the Oxford American more than a decade ago, Mr. Bland “had exceptional delivery and understanding. He made you understand what the song means to him. He didn't just shuffle through, you know—it's also blood and guts…Listen to "Share Your Love with Me," the one with the strings—that's my favorite. That one, and "Two Steps from the Blues" are the two that stick out for me. I have to say that I've never heard records any better than those. No gimmicks, just pure blues pop.”

It was within the conventions of the pop-Soul ballad that Mr. Bland’s vocal skills were most pronounced. One of the best examples (and my favorite) was the 1969 recording “Chains of Love.” Written by Ahmet Ertegun (using his own pseudonym) and recorded in 1951 by Big Joe Turner (of “Shake, Rattle & Roll” fame) as a Big Band toe-tapper, Mr. Bland’s version of “Chains of Love” is a thesis in despair. Few begged as well as Mr. Bland did in his day—it was indeed part of his appeal—and “Chains of Love” is classic example. It’s in the last verse of the song that Mr. Bland gets at the sense of despair as he sings, “well it’s 3 O’ Clock in the morning—lawd and the moon is shining bright….and I was just sitting here wondering, lawd (hiccup) where can you be tonight.” With his reading of those lyrics, Mr. Bland conjures a simple man sitting on his porch rocking his body back and forth recalling the classic “Trouble in Mind” (“I’m going down to the river…if the blues don’t get me, I might have to rock on away from here”). “Chains on Love” was one of the many songs included on Mick Hucknall’s (former lead of Simply Red) 2008 recording Tribute to Bobby.

Lost in the shuffle as ABC-Dunhill was sold to MCA, and clearly on the back-burner at MCA, Mr. Bland eventually found a new home at Malaco Records, which throughout the 1980s was one a the few labels still committed to recording what might be termed as “Southern Soul.” The first project for Mr. Bland at Malaco was Members Only (1985). The title track and lead single would become Mr. Bland’s last song to appear on the R&B charts, though it also earned him a new following on the festival circuit alongside acts like B.B. King and Buddy Guy.

“Members Only” was also a track that brought Mr. Bland in conversation with the Hip-Hop generation—and later Mr. Carter. “Members Only” was written by Larry Addison, who was a former vocalist for the group Freedom, most well known for their 1980 classic “Get Up and Dance.” “Members Only” was sampled by both Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five on “Freedom” (1980) and the Crash Crew on “High Power Rap” (recording as Disco Dave and the Force of 5 MCs in 1980)—the latter song featuring the “Girls, Girls, Girls” hook that producer Just Blaze built Jay Z’s “Girls, Girls, Girls” (2001) from, and which appears on the same 2001 Blueprint album that “Heart of the City (Ain’t No Love)” appears, raising the distinct possibility that “Jay Z Blue” might also be called Jay Z—“Blue Bland.”

“Members Only” was also a track that brought Mr. Bland in conversation with the Hip-Hop generation—and later Mr. Carter. “Members Only” was written by Larry Addison, who was a former vocalist for the group Freedom, most well known for their 1980 classic “Get Up and Dance.” “Members Only” was sampled by both Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five on “Freedom” (1980) and the Crash Crew on “High Power Rap” (recording as Disco Dave and the Force of 5 MCs in 1980)—the latter song featuring the “Girls, Girls, Girls” hook that producer Just Blaze built Jay Z’s “Girls, Girls, Girls” (2001) from, and which appears on the same 2001 Blueprint album that “Heart of the City (Ain’t No Love)” appears, raising the distinct possibility that “Jay Z Blue” might also be called Jay Z—“Blue Bland.”The first of nine studio albums that Mr. Bland recorded for Malaco, Members Only was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1986 (one of four Grammy Award nominations that Mr. Bland earned). Mr. Bland was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992.

Charles Farley’s 2011 biography, Soul of the Man: Bobby “Blue” Bland, was a fitting tribute to an artist, who by that time was suffering the ravages of more than fifty years on the road. That Mr. Bland lived to age 83 is an amazing story in and of itself, given the number of his peers from that generation that had passed on before him.

There’s no small irony in the fact that the Kanye West sample of “Heart of the City (Ain’t No Love”) that appears in the Chrysler 300 add was absent the voice of Mr. Bland. Yet for those who were aware of the commercial’s lineage, it was perhaps the way that Mr. Bland might have preferred it. Mr. Bland literally drove R&B and Soul music for at least two generations, stopping to give Hip-Hop a ride along the way. We will never see another figure like Mr. Bobby “Blue” Bland, and indeed that will be his most lasting legacy.

There’s no small irony in the fact that the Kanye West sample of “Heart of the City (Ain’t No Love”) that appears in the Chrysler 300 add was absent the voice of Mr. Bland. Yet for those who were aware of the commercial’s lineage, it was perhaps the way that Mr. Bland might have preferred it. Mr. Bland literally drove R&B and Soul music for at least two generations, stopping to give Hip-Hop a ride along the way. We will never see another figure like Mr. Bobby “Blue” Bland, and indeed that will be his most lasting legacy.***

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of several books, including the recently publish Looking for Leroy:Illegible Black Masculinities (NYU Press). He is the host of the weekly webcast of Left of Black , produced in conjunction with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University, where Neal is Professor of Black Popular Culture in the Department of African & African-American Studies. He listens to Bobby “Blue” Bland’s “Turn on Your Love Light,” as often as possible.

Published on July 07, 2013 19:10

Darlene Love, Merry Clayton and Lisa Fischer Talk 'Twenty Feet from Stardom'

TimesTalks

Morgan Neville, director of Twenty Feet From Stardom, along with Merry Clayton, Lisa Fischer and Darlene Love, three of the film's stars, sit down with New York Times pop music critic Jon Pareles -- www.timestalks.com. Morgan Neville tells the story of how the film came to be made. Merry Clayton, Lisa Fischer and Darlene Love share their experiences over their accomplished careers in the music business.

Published on July 07, 2013 09:45

July 6, 2013

16-year-old Canadian WondaGurl Discusses Producing on Jay Z's 'Magna Carta Holy Grail'

CBCtheNational

Meet WondaGurl--Ebony Oshunrinde--a Canadian teen featured on Jay-Z's new album, Magna Carta Holy Grail.

Published on July 06, 2013 15:17

Booker T: "My Music Should Be The Soundtrack To Your Life"

Published on July 06, 2013 11:55

Trailer: 'Twenty Feet from Stardom'—the story of Black Women Backup Singers

Radius TWC

Meet the unsung heroes behind the greatest songs of our time. In his compelling new film TWENTY FEET FROM STARDOM, award-winning director Morgan Neville shines a spotlight on the untold true story of the backup singers behind some of the greatest musical legends of the 21st century. Along with rare archival footage and a peerless soundtrack, TWENTY FEET FROM STARDOM boasts intimate interviews with Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Wonder, Mick Jagger and Sting to name just a few. However, these world-famous figures take a backseat to the diverse array of backup singers—including Darlene Love, Merry Clayton, Claudia Lennear, Lisa Fischer, and Judith Hill—whose lives and stories take center stage in the film.

Published on July 06, 2013 07:54

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.