Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 775

November 29, 2014

"Black Lives Make America Matter"--Scholar Jeffrey Q. McCune on the Ground in #Ferguson

The Root.com

The Root.comIn this preview of the next Left of Black , Jeffrey Q. McCune, Associate Professor of Women, Gender, & Sexuality Studies and Performing Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, describes the organizing on the ground in Ferguson and the importance of utilizing the resources of universities and colleges for the communities around them. McCune is the author of Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and the Politics of Passing (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Published on November 29, 2014 19:58

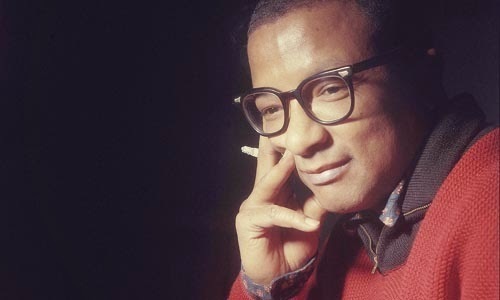

Billy Strayhorn: "Lush Life" (1964)

Birthday (November 29) of Billy Strayhorn (1915-1967), the legendary composer, pianist, and long-time Duke Ellington collaborator, most well known for the Ellington standard "Take the A Train," "Satin Doll," "Chelsea Bridge," and "Lush Life," which Strayhorn performs here.

Published on November 29, 2014 11:56

November 28, 2014

The Spin w Esther Armah: Mike Brown & Marissa Alexander: Justice in 21st Century US

The Spin with Esther Armah

The Spin with Esther Armah* Mike Brown & Marissa Alexander: Justice in 21st Century US

* Bill Cosby & Sexual Assault Allegations

Contributors: Monifa Bandele, dream hampton, Sofia Quintero

Published on November 28, 2014 16:57

"The People" -- De La Soul feat. Chuck D

De La Soul

De La Soul

The idea for the song came from a couple of samples, and the track's vibe is earnest and has a pressing tone to it. The lyrics are commentaries of our struggles and successes, our weaknesses and strengths... the experiences... and trials and tribulations we have faced as human beings, a race, and as individuals. Lyrically Chuck brings a sense of authority and urgency. The power in his voice demands your attention. With Chuck on the track this is a dream come true for us. Originally "The People" was suppose to drop in June around the same time the Chuck D/Hot 97/Peter Rosenberg situation took place. We chose to hold off and not add fuel to any fires. Our next aim was for a Black Friday release. Coincidentally the Ferguson tragedy took place, and more recently the non-indictment verdict. Somehow this song was destined to be a part of something more than just dropping a joint. We hope it will lend itself to something positive in these difficult times.

Published on November 28, 2014 12:40

The Day After… by Brothers Writing to Live

Sam Middleton, 'Untitled' (1961)The Day After…by Brothers Writing to Live | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Sam Middleton, 'Untitled' (1961)The Day After…by Brothers Writing to Live | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

It’s Wednesday, November 26th.

Today is the day after the day after a day a grand jury in St. Louis, MO, decided against indicting Ferguson police officer, Darren Wilson, who killed 18-year old Mike Brown, Jr.

Just forty-eight hours ago, we waited anxiously believing, for once, that our legal system would prove us wrong. We thought: surely, justice would prevail this time. We were hopeful and not yet completely rage-filled and heart broken. We had yet to scream, “Fuck White racists. To hell with Black apologists demanding us to calm down--reminding us that Mike Brown's actions got him killed and not his color. We refuse to listen to any POTUS, even the Black one, who points a finger at us as and not the fucked up state systems demeaning and deadening us under their watch.”

No. We still had faith in a rigged system, despite the constant reminder that Black lives aren’t valued in empires—even those built on our backs.

We urged ourselves to believe America would not fail its Black citizenry again.

We chose to suspend history and focus on what could be as opposed to what was and still is: That Black people were deemed three-fifths of a human in our country’s founding documents; That our bodies have been subjected to slave codes, Black codes, rapes, lynchings, Jim Crow laws, the war on drugs, and the prison industrial complex; That White vigilantes like George Zimmerman walk free after murdering Black kids like Trayvon Martin and some other will use a shotgun to kill our little sister, Renisha McBride.

And while we hoped and prayed and put faith in the system, the system (and its agents) verified that Black life doesn’t mean shit in these states. In fact, the law tends to overly protect White police and White vigilantes. The law tends to serve those who brutally execute Black people because White people are considered arbiters and the embodiment of the “law.” But, two days later, highways continue to be shut down, streets continue to be blocked, once comfortable lives have been disrupted, truth has been told, fists remain raised, and a people are wide awake. We say: No more.

No more die-ins and the donning of hoodies as performative gestures meant to indicate our refusal to be killed. No more. We support every Black person, and ally, who is resisting and protesting a system that failed to bring about justice for Mike Brown's family.

No more hashtag memorials and silent vigils in memory of 12-year old kids shot dead for holding toy guns by a police who would sooner protect a White card carrying NRA member than any unarmed Black person. No more. No more protecting corporate media outlets who speak more kindly of White criminals than they do Black victims. No more.

We are creative and imaginative enough to dream and build new methods of public safety in our communities because we cannot be sure that our calling the police for help might be a reason some cop, who sees us as "demons" as opposed to human beings who bleed and hurt, decides to slam us on our heads, choke us, pound us repeatedly, pull out a gun on us, shoot us.

No more. Our Black bodies are not yours to pillage and dispose of. And forty-eight hours later we are writing to remind you that we will not forget. There can be no peace without justice. There can be no peace as long as police-vigilante-murderers are allowed to go free.

We will not forget that our legal system continues to legitimize anti-Black, state sanctioned violence. We stand in solidarity with Mike Brown's family and other families of those Black people who have been murdered by police. We are in solidarity with the brave among us who have laid their bodies on asphalt-paved highways to shut shit down for justice. We are in solidarity with those who wake up with voices lost, should they be able to speak, after spending nights upon nights screaming chants that urge us toward transformation and revolution.

The day after today and the day after that, and many days after, we will not forget. We are not your strange fruit. We will fight. And we will live.

Signed, Brothers Writing To LiveKiese Laymon, Writer & Professor at Vassar CollegeMychal Denzel Smith, Writer, Mental Health Advocate, & Cultural CriticKai M. Green, Writer, Filmmaker, & Postdoctoral Fellow at Northwestern UniversityNyle Fort, Minister, Writer, and Community OrganizerMarlon Peterson., Writer & Youth & Community AdvocateMark Anthony Neal, Writer, Cultural Critic, & Professor at Duke UniversityHashim Pipkin, Writer, Cultural Critic, Ph.D. Candidate at Vanderbilt UniversityWade Davis, II, Writer, LGBTQ Advocate, & Former NFL PlayerDarnell L. Moore, Writer & Activist

Published on November 28, 2014 06:49

November 27, 2014

The Fire This Time

The Fire This Timeby Timothy Patrick McCarthy | @DrTPM | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Ferguson has finally broken us. We can no longer pretend to dream of a better America unless—and until—we reckon with the worst of America. To continue to dream right now is an act of willful ignorance, or hopeless naiveté. This is a fucking nightmare. And we’re all implicated.During the most difficult times, I always return to James Baldwin, especially his 1963 masterpiece The Fire Next Time—for inspiration and solace, in equal measure. This passage always, always speaks to me:“Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, staples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death—ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us. But white Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them. And this is also why the presence of the Negro in this country can bring about its destruction. It is the responsibility of free men to trust and to celebrate what is constant—birth, struggle, and death are constant, and so is love, though we may not always think so—and to apprehend the nature of change, to be able and willing to change. I speak of change not on the surface but in the depths—change in the sense of renewal. But renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant that are not—safety, for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope—the entire possibility—of freedom disappears.” Freedom has always been good at staging a disappearing act. The American Revolution was fueled by freedom (they preferred to call it “liberty” back then), but the original intent was always meant for a small minority. The Civil War brought about a “new birth of freedom”—for 4 million formerly enslaved people who might finally become “citizens”—but that dream was soon deferred by new kinds of racism: poll taxes and black codes, literacy texts and lynchings, white hoods and white nostalgia. Throughout the 20th century, the “New Deal,” “Fair Deal,” “New Frontier,” and “Great Society” all promised African Americans a better life, but they were always the first ones to be thrown under the bus—even when they were in back of the bus or refused to ride the bus—whenever someone needed to be left behind the bus. The darkest truth of our democracy is that black lives have never mattered nearly as much as white ones have. There’s a reason why the Civil War has been called the “Second American Revolution,” and the Civil Rights Movement has been called the “Second American Reconstruction,” because when it comes to the rights of black folk, America has a long history of getting it wrong the first time around. And the second time around. And this time around.That’s what I was thinking about as I awaited the long-awaited press conference in Ferguson, Missouri. I’ve been teaching a course, “Stories of Slavery and Freedom,” this semester, and I gave my students the day off yesterday because it’s Thanksgiving week; they’re tired and so am I. When I made the decision to give them a break, I had no idea that the Ferguson verdict—and make no mistake, it was its own indictment—would be coming down this week. But it did. And it got me thinking about all the legacies of slavery and freedom that we’ve been studying this term: the unspeakable tragedy of the Middle Passage and how it forced African people to make the most hideous decisions about life and death; the uncertainty of the Atlantic World and how it required some black people to broker their existences and identities in the fleeting hope of avoiding lives of perpetual bondage; the uncharted territory of people like James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, Phillis Wheatley, and Olaudah Equiano who tried to write themselves into existence against all odds; the uncommon courage of people like Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, Prince Hall, Daniel Coker, James Forten, Russell Parrott, Prince Saunders, Robert Alexander Young, John Brown Russwurm, Samuel Cornish, and others who were the first to speak out against racism in the new nation; the undeniable radicalism of David Walker, Maria Stewart, Frederick Douglass, David Ruggles, Henry Highland Garnet, Solomon Northup, Sojourner Truth, William Wells Brown, Mary Ann Shadd, Martin Delany, Harriet Wilson, Harriet Jacobs, and so many others who dared to defy a slave nation built on both white supremacist and patriarchal practices. I could go on. That’s the thing about the long black freedom struggle: it’s long, it’s black, and it’s a constant struggle. The rest of America would do well to learn this history.As I waited for the “inevitable” in Ferguson, I couldn’t help but wonder: when and where did America’s fear of black men—boys, teenagers, grown men, every one of them—come from? Did it come from the Haitian Revolution, the most successful slave rebellion in the modern world? Did it come from Nat Turner, who led the largest slave rebellion in American history, one that killed about 60 whites but also led to the reactionary and indiscriminate murder of even more blacks? Did it come from Uncle Tom, who got too close to Little Eva in that famous work of fiction that clearly cut too close to home? Did it come from the 178,000-plus black troops who fought against the Confederacy in the Civil War? Did it come from the nearly 3500 black men who were lynched between 1882 and 1968? Did it come from Bigger Thomas, or Emmett Till? Did it come from the black folks in the 1960s who finally got fed up after waiting for 100 years (or was is 200? 300?) for freedom? Did it come from losing Martin and Malcolm—the yin and the yang of anxious white fantasies—at the same time? Did it come from the “deadbeat dads,” or “gangsta rappers,” or “crack addicts,” or “big ballers,” or “the first black President”—or was it Cosby who finally pushed America over the edge? Or is it all of the above? Like Langston’s raisin in the sun, history explodes with questions right now, but this one haunts me: Will America ever know the origin of it all—why Skittles and Swisher Sweets make white people so crazy they commit murder?But enough of history. If we knew our history, or cared about it, we wouldn’t repeat it so much. So here’s what’s on my heart tonight:Grief and relief. My heart breaks for Michael Brown’s family—and all black families who have to deal with the terror of mourning the loss of a child stolen from them. Since August 9, 2014, when their unarmed son was murdered by Ferguson police office Darren Wilson, Lesley McSpadden and Michael Brown, Sr., have been living with a grief that none of us who haven’t lost a loved one in this way will ever be able to fully understand. It’s especially hard for most white people to comprehend this kind of loss, because we don’t die this way. The only reason I can empathize with this at all is because I helped to raise a black child, my brother Malcolm, who spent much of his childhood navigating a treacherous world where he was harassed by police officers going and coming—Cambridge cops who followed him home when he was going to his mother’s apartment in Central Square, and Harvard cops who followed him home when he was coming to my apartment in Quincy House. (I won’t even talk about the appearance he had to make in front of a juvenile court judge when he was 12 years old after defending his best friend against a white bully on the playground.) Like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Malcolm was a black teenager. And like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Malcolm was a good kid who always worked hard to live a good life against the odds. Malcolm’s mother and I both had “the talk” with him early on: be polite, come right home, don’t wear a hoodie. Unlike Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Malcolm is still alive, and we all count our blessings every day. But we also know that Malcolm will always be “at risk” in America, even though he shouldn’t be, even though he doesn’t deserve to be. After the grand jury’s verdict last night, I texted Malcolm: “I love you.” After telling me he loves me, too, he responded: “Shit won’t change.” It breaks my heart that he feels this way, but who am I to tell him he’s wrong? Rage and resignation. Our system is broken. No one who lives in cities can be naïve about cops. I’ve lost track—ever since my days in Rudy Giuliani’s New York City in the 1990s—of the number of protests I’ve attended in response to instances of white police brutality against innocent black people. The Ferguson spectacle is yet another trigger warning for the nation, an indictment of the entire system. Make no mistake: the grand jury proceedings, Robert McCulloch’s announcement, the police behavior before and after August, even the President’s late-night press conference—taken together, they represent a wholesale incapacity of our system to deliver real justice when it comes to white-on-black violence. Indeed, McCulloch’s press statement was a textbook performance in white supremacy, bookended with empty expressions of sympathy for a real family in deep grief. Given the long history of this kind of behavior in America, it’s hard to understand how ordinary citizens—perpetually alienated, rarely represented or respected—are supposed to act during times of crisis. When there is no legitimate recourse within powerful institutions that insist on representing themselves as “representative,” there is no other choice but to rage against the machine, peacefully or otherwise. I feel this rage in my bones, even more so when people in power call for “peace” and caution against “violence” even as they refuse to hold themselves—and their peers—to the same standard. I worked hard to get President Obama elected, many of us did, and I recognize how constrained (and obstructed) he’s been by the tenacity of American racism. It’s real. But watching him deliver that lifeless statement in the wake of the Ferguson verdict, feeling his constraint in a way I have never felt before, I can’t help but think that we’ve all fooled ourselves into hoping that the “first black President” could change anything. My late mentor Manning Marable once cautioned: “a black face in a high place does not mean there is racial justice.” I’ve never fully resigned myself to the truth of this until recently. When historians mark the death of Barack Obama’s Presidency, it will not be November 4, 2014. It will be November 24, 2014.Hate and hope. On occasion, I have been known to say: “I hate white people.” This is meant to be provocative, of course, but it’s also a genuine expression of what I too often think and feel. Some of my white friends understand what I mean when I say this; nearly all of my black friends do. But let me be absolutely clear about what I mean: of course I don’t hate all people with white skin (for instance, I love my mom and my dad, and some of my best friends are white), but I hate the fact that so many white people have a possessive-obsessive investment in whiteness; I hate the fact that so many white people do not—and cannot—understand or appreciate or empathize with what black people live with on a daily basis; I hate the fact that so few white people know anything about black history; I hate slavery and segregation and how both continue to shape our lives, in every school and neighborhood in America; and I hate it when white people get so defensive every time anyone criticizes white people or challenges white privilege. This is what I hate. November 24th was another moment of reckoning for white America: on which side of history do we stand? I realize this may come across as “divisive,” so let me also say this: I was buoyed that night by how many of my white friends—hundreds on my newsfeed alone—were also outraged by what has happened in Ferguson. That shared outrage, which I frankly didn’t expect, gave me the energy to get up the following morning and keep fighting for this country. Black lives and white lives should matter to each other. We are inextricably bound in America. For better and for worse, we always have been and always will be. We may wish to deny this fact, and even hope for our separation, but we do so at our own continued peril. If there’s anything that’s clear to me about this country, it’s this: despite our best efforts at separation, we have failed miserably. Ferguson is yet another reminder—this time for worse—of this longstanding truth. The dilemma that confronts us, still, is whether we will destroy one another before we learn, at last, to love each other.In the wake of Ferguson, let us not be distracted or deterred from the work that remains unfinished. As James Baldwin concluded in The Fire Next Time: “Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we—and now I mean the relative conscious whites and the relative conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of others—do no falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, recreated from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!”Fifty-one years ago, this was as much a challenge as it was a prophecy. It remains so.***Timothy Patrick McCarthy, Ph.D. is an award-winning scholar, teacher, and activist. He holds a joint faculty appointment in Harvard’s undergraduate honors program in History and Literature and at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he is founding director of the Sexuality, Gender & Human Rights Program at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. A historian of politics and social movements, he is author or editor of five books, including The Radical Reader: A Documentary History of the American Radical Tradition (2003), Prophets of Protest: Reconsidering the History of American Abolitionism (2006), and Stonewall’s Children: Living Queer History in the Age of Liberation, Loss, and Love, forthcoming from the New Press.

The Fire This Timeby Timothy Patrick McCarthy | @DrTPM | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Ferguson has finally broken us. We can no longer pretend to dream of a better America unless—and until—we reckon with the worst of America. To continue to dream right now is an act of willful ignorance, or hopeless naiveté. This is a fucking nightmare. And we’re all implicated.During the most difficult times, I always return to James Baldwin, especially his 1963 masterpiece The Fire Next Time—for inspiration and solace, in equal measure. This passage always, always speaks to me:“Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, staples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death—ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us. But white Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them. And this is also why the presence of the Negro in this country can bring about its destruction. It is the responsibility of free men to trust and to celebrate what is constant—birth, struggle, and death are constant, and so is love, though we may not always think so—and to apprehend the nature of change, to be able and willing to change. I speak of change not on the surface but in the depths—change in the sense of renewal. But renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant that are not—safety, for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope—the entire possibility—of freedom disappears.” Freedom has always been good at staging a disappearing act. The American Revolution was fueled by freedom (they preferred to call it “liberty” back then), but the original intent was always meant for a small minority. The Civil War brought about a “new birth of freedom”—for 4 million formerly enslaved people who might finally become “citizens”—but that dream was soon deferred by new kinds of racism: poll taxes and black codes, literacy texts and lynchings, white hoods and white nostalgia. Throughout the 20th century, the “New Deal,” “Fair Deal,” “New Frontier,” and “Great Society” all promised African Americans a better life, but they were always the first ones to be thrown under the bus—even when they were in back of the bus or refused to ride the bus—whenever someone needed to be left behind the bus. The darkest truth of our democracy is that black lives have never mattered nearly as much as white ones have. There’s a reason why the Civil War has been called the “Second American Revolution,” and the Civil Rights Movement has been called the “Second American Reconstruction,” because when it comes to the rights of black folk, America has a long history of getting it wrong the first time around. And the second time around. And this time around.That’s what I was thinking about as I awaited the long-awaited press conference in Ferguson, Missouri. I’ve been teaching a course, “Stories of Slavery and Freedom,” this semester, and I gave my students the day off yesterday because it’s Thanksgiving week; they’re tired and so am I. When I made the decision to give them a break, I had no idea that the Ferguson verdict—and make no mistake, it was its own indictment—would be coming down this week. But it did. And it got me thinking about all the legacies of slavery and freedom that we’ve been studying this term: the unspeakable tragedy of the Middle Passage and how it forced African people to make the most hideous decisions about life and death; the uncertainty of the Atlantic World and how it required some black people to broker their existences and identities in the fleeting hope of avoiding lives of perpetual bondage; the uncharted territory of people like James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, Phillis Wheatley, and Olaudah Equiano who tried to write themselves into existence against all odds; the uncommon courage of people like Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, Prince Hall, Daniel Coker, James Forten, Russell Parrott, Prince Saunders, Robert Alexander Young, John Brown Russwurm, Samuel Cornish, and others who were the first to speak out against racism in the new nation; the undeniable radicalism of David Walker, Maria Stewart, Frederick Douglass, David Ruggles, Henry Highland Garnet, Solomon Northup, Sojourner Truth, William Wells Brown, Mary Ann Shadd, Martin Delany, Harriet Wilson, Harriet Jacobs, and so many others who dared to defy a slave nation built on both white supremacist and patriarchal practices. I could go on. That’s the thing about the long black freedom struggle: it’s long, it’s black, and it’s a constant struggle. The rest of America would do well to learn this history.As I waited for the “inevitable” in Ferguson, I couldn’t help but wonder: when and where did America’s fear of black men—boys, teenagers, grown men, every one of them—come from? Did it come from the Haitian Revolution, the most successful slave rebellion in the modern world? Did it come from Nat Turner, who led the largest slave rebellion in American history, one that killed about 60 whites but also led to the reactionary and indiscriminate murder of even more blacks? Did it come from Uncle Tom, who got too close to Little Eva in that famous work of fiction that clearly cut too close to home? Did it come from the 178,000-plus black troops who fought against the Confederacy in the Civil War? Did it come from the nearly 3500 black men who were lynched between 1882 and 1968? Did it come from Bigger Thomas, or Emmett Till? Did it come from the black folks in the 1960s who finally got fed up after waiting for 100 years (or was is 200? 300?) for freedom? Did it come from losing Martin and Malcolm—the yin and the yang of anxious white fantasies—at the same time? Did it come from the “deadbeat dads,” or “gangsta rappers,” or “crack addicts,” or “big ballers,” or “the first black President”—or was it Cosby who finally pushed America over the edge? Or is it all of the above? Like Langston’s raisin in the sun, history explodes with questions right now, but this one haunts me: Will America ever know the origin of it all—why Skittles and Swisher Sweets make white people so crazy they commit murder?But enough of history. If we knew our history, or cared about it, we wouldn’t repeat it so much. So here’s what’s on my heart tonight:Grief and relief. My heart breaks for Michael Brown’s family—and all black families who have to deal with the terror of mourning the loss of a child stolen from them. Since August 9, 2014, when their unarmed son was murdered by Ferguson police office Darren Wilson, Lesley McSpadden and Michael Brown, Sr., have been living with a grief that none of us who haven’t lost a loved one in this way will ever be able to fully understand. It’s especially hard for most white people to comprehend this kind of loss, because we don’t die this way. The only reason I can empathize with this at all is because I helped to raise a black child, my brother Malcolm, who spent much of his childhood navigating a treacherous world where he was harassed by police officers going and coming—Cambridge cops who followed him home when he was going to his mother’s apartment in Central Square, and Harvard cops who followed him home when he was coming to my apartment in Quincy House. (I won’t even talk about the appearance he had to make in front of a juvenile court judge when he was 12 years old after defending his best friend against a white bully on the playground.) Like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Malcolm was a black teenager. And like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Malcolm was a good kid who always worked hard to live a good life against the odds. Malcolm’s mother and I both had “the talk” with him early on: be polite, come right home, don’t wear a hoodie. Unlike Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Malcolm is still alive, and we all count our blessings every day. But we also know that Malcolm will always be “at risk” in America, even though he shouldn’t be, even though he doesn’t deserve to be. After the grand jury’s verdict last night, I texted Malcolm: “I love you.” After telling me he loves me, too, he responded: “Shit won’t change.” It breaks my heart that he feels this way, but who am I to tell him he’s wrong? Rage and resignation. Our system is broken. No one who lives in cities can be naïve about cops. I’ve lost track—ever since my days in Rudy Giuliani’s New York City in the 1990s—of the number of protests I’ve attended in response to instances of white police brutality against innocent black people. The Ferguson spectacle is yet another trigger warning for the nation, an indictment of the entire system. Make no mistake: the grand jury proceedings, Robert McCulloch’s announcement, the police behavior before and after August, even the President’s late-night press conference—taken together, they represent a wholesale incapacity of our system to deliver real justice when it comes to white-on-black violence. Indeed, McCulloch’s press statement was a textbook performance in white supremacy, bookended with empty expressions of sympathy for a real family in deep grief. Given the long history of this kind of behavior in America, it’s hard to understand how ordinary citizens—perpetually alienated, rarely represented or respected—are supposed to act during times of crisis. When there is no legitimate recourse within powerful institutions that insist on representing themselves as “representative,” there is no other choice but to rage against the machine, peacefully or otherwise. I feel this rage in my bones, even more so when people in power call for “peace” and caution against “violence” even as they refuse to hold themselves—and their peers—to the same standard. I worked hard to get President Obama elected, many of us did, and I recognize how constrained (and obstructed) he’s been by the tenacity of American racism. It’s real. But watching him deliver that lifeless statement in the wake of the Ferguson verdict, feeling his constraint in a way I have never felt before, I can’t help but think that we’ve all fooled ourselves into hoping that the “first black President” could change anything. My late mentor Manning Marable once cautioned: “a black face in a high place does not mean there is racial justice.” I’ve never fully resigned myself to the truth of this until recently. When historians mark the death of Barack Obama’s Presidency, it will not be November 4, 2014. It will be November 24, 2014.Hate and hope. On occasion, I have been known to say: “I hate white people.” This is meant to be provocative, of course, but it’s also a genuine expression of what I too often think and feel. Some of my white friends understand what I mean when I say this; nearly all of my black friends do. But let me be absolutely clear about what I mean: of course I don’t hate all people with white skin (for instance, I love my mom and my dad, and some of my best friends are white), but I hate the fact that so many white people have a possessive-obsessive investment in whiteness; I hate the fact that so many white people do not—and cannot—understand or appreciate or empathize with what black people live with on a daily basis; I hate the fact that so few white people know anything about black history; I hate slavery and segregation and how both continue to shape our lives, in every school and neighborhood in America; and I hate it when white people get so defensive every time anyone criticizes white people or challenges white privilege. This is what I hate. November 24th was another moment of reckoning for white America: on which side of history do we stand? I realize this may come across as “divisive,” so let me also say this: I was buoyed that night by how many of my white friends—hundreds on my newsfeed alone—were also outraged by what has happened in Ferguson. That shared outrage, which I frankly didn’t expect, gave me the energy to get up the following morning and keep fighting for this country. Black lives and white lives should matter to each other. We are inextricably bound in America. For better and for worse, we always have been and always will be. We may wish to deny this fact, and even hope for our separation, but we do so at our own continued peril. If there’s anything that’s clear to me about this country, it’s this: despite our best efforts at separation, we have failed miserably. Ferguson is yet another reminder—this time for worse—of this longstanding truth. The dilemma that confronts us, still, is whether we will destroy one another before we learn, at last, to love each other.In the wake of Ferguson, let us not be distracted or deterred from the work that remains unfinished. As James Baldwin concluded in The Fire Next Time: “Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we—and now I mean the relative conscious whites and the relative conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of others—do no falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, recreated from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!”Fifty-one years ago, this was as much a challenge as it was a prophecy. It remains so.***Timothy Patrick McCarthy, Ph.D. is an award-winning scholar, teacher, and activist. He holds a joint faculty appointment in Harvard’s undergraduate honors program in History and Literature and at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he is founding director of the Sexuality, Gender & Human Rights Program at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. A historian of politics and social movements, he is author or editor of five books, including The Radical Reader: A Documentary History of the American Radical Tradition (2003), Prophets of Protest: Reconsidering the History of American Abolitionism (2006), and Stonewall’s Children: Living Queer History in the Age of Liberation, Loss, and Love, forthcoming from the New Press.

Published on November 27, 2014 08:21

November 26, 2014

12 Things White People Can Actually Do After the Ferguson Decision

12 Things White People Can Actually Do After the Ferguson Decision

12 Things White People Can Actually Do After the Ferguson Decision

by Joseph Osmundson and David J. Leonard | Huffington Post

In the wake of the decision in Ferguson, and the killing of Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio and Akai Gurley in New York, righteous anger is boiling over on the streets, on social media and within our everyday lives. So many of us feel so powerless, unable to affect substantive change, unable to do anything other than hurt. Powerless does not mean there isn't work to be done. It is silence, inactivity, complacency and disconnect that are the enemies of justice, not rage.White people of good conscious, too, want to act in solidarity in the fight for racial justice, but may feel cut off from the communities or resources necessary to do so. The feelings of disconnect from these movements, from the rage, from tears and from injustice warrant interrogation. So does the cycle of injustice, followed by shock, silence, articles on "we can do," and a return to our everyday lives.This cannot simply be about performing change and solidarity; it cannot be about doing without accountability and sacrifice.We were struck by a recent piece that suggested 12 things white people can do in the wake of the Ferguson; all but one of the suggestions involved only thinking, reading, contemplating, reframing. While these personal acts are absolutely necessary, they are insufficient. They are not enough, and especially not today. They fall short because they don't facilitate change, because they don't hold whiteness accountable, and because they aren't sufficiently tied into movements of racial justice. And so, we would like to offer a list of 12 actual things white people can do to act today, tomorrow, next week, next year.1. Listen. What are activists of color and organizations on the ground in your community asking for? What do they need? If you don't know any organizations locally, the internet is a great resource. Activists in Ferguson have been vocal about their needs. Listen, and then do. Look into the work of Black Youth Project, Dream Defenders, Blackout for Human Rights, Ferguson Action, Organization of Black Struggle and Black Life Matters. It's not about our needs and our desires, but about listening, and then as @prisonculture reminds us, actually doing the work.2. Protest. There have been calls in major cities for protest. A list of protests is available online. Go. It is time to put our (white) bodies on the line in solidarity for racial justice. Bring a friend. Make a sign. Say #enough. Be accountable because there is no justice without racial justice. There is no movement forward without standing up against racial terror. There is no change without protest, without agitation, without sacrifice and without a challenge the very fabric of the nation.3. Take Action Beyond Ferguson. This is not an isolated incident and does not call for an isolated response. Demand justice for Mike Brown; for Marissa Alexander. Demand justice for the all too many people who were killed at the hands of police. Take action that changes how we think about policing, safety and security. Give money, time and resources to individuals and organizations doing work to fight police repression (stop-and-frisk; racial profiling the school-to-prison pipeline), and not just today. Invest in alternative media outlets such as the Feminist Wire, Race Forwardand Colorlines, which challenge the widespread criminalization of black bodies.4. Do Not Police Others' Reactions. It is not really our place to call for peaceful responses, or to call out looting as irresponsible or counterproductive. Loss of life is tragic, anger is justified, not all protests by black bodies are riots. The same state forces that violently end black life every 28 hours are condemning theft as irresponsible. The same system that denies justice, that kills with impunity, that denies the innocence of black men and women, young and old, isn't the basis of justice. Stay woke.5. If You Belong to a Faith Community, Take Action There. Simply reading scriptures with a social justice lens is necessary but not sufficient. Organize fundraisers in your communities to fight for justice. Bring your communities to actions, protests. Make sure that race (and gender, and class and sexuality) is not silent and invisible in your faith communities, even if they are predominantly white. Speak up, even and maybe especially if you are met with discomfort or resistance.6. Know History. To understand the stakes requires understanding the history of racial violence, and the failures of the criminal (in)justice system to hold America accountable throughout America's short history. To understand rage, to understand white supremacy and the patterns of violence, and steps forward means knowing the history of lynchings and the Scottsboro boys; of Emmett Till and 4 Little Girls, of Sean Bell and Renisha McBride. The history of change, of organizing, or "ceaseless agitation" offers us a blueprint for action.7. If You Can, Give Money to Organizations That Are Doing Work on the Ground Locally or Nationally. Organizations doing truly radical and transformative work may have a hard time securing adequate funding from within the often-conservative philanthropic world. Do your research, and give. Here are a few of our favorite orgs: Ferguson Defense Fund; Youth Justice Coalition; DRUM NYC;Color of Change; Showing up for Racial Justice.8. If You See Injustice Occurring, Do Not Stand Silently or Walk on By. Do you see police officers engaging in a stop-and-frisk interaction? It turns out that it is entirely legal to film police interactions without interfering. Hold police accountable. Watch them. They may be less likely to engage in outright violence if they are being filmed. If not, the video can be critical evidence as police can claim that they were being assaulted, or charge disorderly conduct, when video evidence clearly refutes these claims. There are apps and organizations that accumulate these videos and data. Use them.9. When You Hear Racism From Your Community, Silence Is No Longer a Possibility. We know that it can be uncomfortable to speak up, but it is necessary. We know how white people can speak when no one else is in the room. We know how blatant racism can still be. We choose to speak, even if it is uncomfortable.10. Dream Big. Imagining a future without racism is damn near impossible given the ways in which discrimination are built into our institutions. Seeing systemic racism is step one. Do that reading, thinking, self-reflection. Imaging a future without it is the necessary step two. What alternative models are there of policing? What might a just criminal justice system look like? Really consider breaking down institutions and building them anew, and then connect with organizations whose visions you love.11. Do Something Beyond This Week. Action has never come about through silence; change has not come through the process but instead via movements that have demanded it. That requires more than reading and responding during this initial swell of outrage. It requires action here and now, tomorrow and into the future. It requires change to laws, to our institutions and how we carry ourselves each and every day.12. Be Accountable. This week, many families will gather together to give thanks. That this holiday also marks the beginning of the American war against indigenous populations is something we must also reflect upon; it is a reminder of how deeply white supremacy is engrained in our history and culture. It is also an opportunity to hold our family and friends accountable, to ask what they are doing to foster change, and to challenge the lies and misinformation that are being spread in the name of racial injustice. Every year, at my family's Thanksgiving, we read a poem to remember the genocide against the American Indians. It is a small step, but it breaks the silence. This work is not easy, but the stakes are too high. Just ask the families of Eric Garner, Mike Brown, Ezel Ford, Kajieme Powell, Vonderitt D. Meyers, Jr., John Crawford III, Cary Ball Jr. Aura Rain Rosser, Renisha McBride, Trayvon Martin and so many more whose names we might not even know, whose hopes and dreams were cut short, whose families are, even now, gathering not to celebrate but to mourn.***Joseph Osmundson is a scientist, writer and educator born and raised in the rural Pacific Northwest. His research focuses on protein structure and function while his writing explores identity and place and sexuality and class and race and all sorts of messy, complicated stuff. His work has been published on Gawker, and he will have an essay included in the upcoming anthology The Queer South (Sibling Rivalry Press) due out in the Fall of 2014. He has taught at The New School and Vassar College and is currently a postdoctoral fellow in Systems Biology at New York University. You can follow him on Twitter at @reluctantlyjoe and read his writings at www.josephosmundson.com.David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. Leonard's latest books include After Artest: The NBA and the Assault on Blackness (SUNY Press), African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (Praeger Press) co-edited with Lisa Guerrero and Beyond Hate: White Power and Popular Culture with C. Richard King. He is currently working on a book Presumed Innocence: White Mass Shooters in the Era of Trayvon about gun violence in America. You can follow him on Twitter at @drdavidjleonard.

Published on November 26, 2014 19:45

The Illipsis: Jay Smooth on Ferguson, Riots & Human Limits

Fusion | The Illipsis

Fusion | The Illipsis

In this second installment of The Illipsis, Jay Smooth looks back at the week's events in #Ferguson and asks how we can truly apply Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s advice that "riots are the language of the unheard."

Published on November 26, 2014 19:20

November 25, 2014

Art on Wax: Triumph And Struggle—A Black Sonic Narrative

Art on Wax

Art on Wax

Triumph & Struggles: A Black Sonic Narrative is a curated mix of songs that demonstrate forms of expression against systematic oppression. Rhythm is woven into the fibre of our beings. We use music to celebrate our joys, channel our Black rage and soothe our pain. During these times when we are on the brink of inevitable change, let us hold to our tradition that is music.1. Assata Shakur

2. Babatunde Olatunji: Oya (Primative Fire) 3. Congregation of New Browns Chapel: Church House Moan 4. Big Mama Thornton: My Heavy Load 5. Aretha Franklin: Wholy Holy 6. Sun Ra Arkestra: Astro Black 7. Richie Havens: Follow The Drinking Gourd 8. Jimi Hendrix: The Star Spangled Banner 9. Public Enemy: Bring The Noise 10. Outkast: Liberation Ft. Erykah Badu, Big Rube, Cee-Lo 11. Eddie Kendricks: My People Hold On 12. James Baldwin 13. Lauryn Hill: Black Rage

Published on November 25, 2014 17:49

Unrest In Ferguson Revives Issues Of Race In Justice System

WUNC | The State of Things

WUNC | The State of Things

A grand jury in St. Louis has decided not to indict Darren Wilson, the white Ferguson police officer who shot and killed 18-year-old Michael Brown, an unarmed black man.

Host Frank Stasio talks with Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African and African-American Studies at Duke University, and Nia Wilson, executive director of the Spirit House in Durham , about the decision and what it means for race relations.

Listen

Published on November 25, 2014 12:37

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.