Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 695

September 23, 2015

PostBourgie: What It Means to Lose a School

'PostBourgie's G.D. and Terryn talk to Jelani Cobb of the

New Yorker

, who went back to his former high school in Queens, which was recently closed down. Jelani was trying to figure out how the diverse, highly regarded school quickly deteriorated quickly after he graduated in the 1980s and soon became, to many, an example of why big, neighborhood schools can't work. And Eve Ewing of Seven Scribes talks to G.D. about the fight to save Walter Dyett High School, the last public school open to everyone in Bronzeville, a historic black neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. Protesters there had been staging a month-long hunger strike to keep Dyett's doors open.'

'PostBourgie's G.D. and Terryn talk to Jelani Cobb of the

New Yorker

, who went back to his former high school in Queens, which was recently closed down. Jelani was trying to figure out how the diverse, highly regarded school quickly deteriorated quickly after he graduated in the 1980s and soon became, to many, an example of why big, neighborhood schools can't work. And Eve Ewing of Seven Scribes talks to G.D. about the fight to save Walter Dyett High School, the last public school open to everyone in Bronzeville, a historic black neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. Protesters there had been staging a month-long hunger strike to keep Dyett's doors open.'

Published on September 23, 2015 20:14

Black Girlhood Takes Center Stage In A Work That's Serious About 'Play'

"Black girls playing; black girl joy" — that's what choreographer Camille A. Brown says her new show is all about. She's taking Black Girl: Linguistic Play to stages, schools and prisons around the U.S.

"Black girls playing; black girl joy" — that's what choreographer Camille A. Brown says her new show is all about. She's taking Black Girl: Linguistic Play to stages, schools and prisons around the U.S.

Published on September 23, 2015 19:52

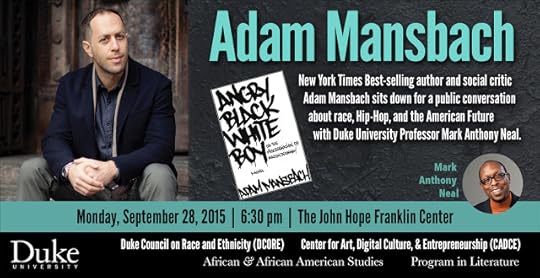

Race, Hip-Hop & The American Future: A Conversation w/ Adam Mansbach @ Duke University on Mon September 28th

The Center for Arts + Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship (CADCE) Presents Race, Hip-Hop & The American Future: A Conversation with Adam Mansbach on Monday, September 28, 2015 at 6:30 pm at the John Hope Franklin Center for International & Interdisciplinary Studies (2204 Erwin Road)

The Center for Arts + Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship (CADCE) Presents Race, Hip-Hop & The American Future: A Conversation with Adam Mansbach on Monday, September 28, 2015 at 6:30 pm at the John Hope Franklin Center for International & Interdisciplinary Studies (2204 Erwin Road)Mansbach's 2013 novel, Rage is Back, was named a Best Book of the Year by NPR and the San Francisco Chronicle and is currently being adapted for the stage; his previous novels include the California Book Award-winning The End of the Jews and the cult classic Angry Black White Boy, taught at more than eighty schools, including at Duke, this semester.

Mansbach is also the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller Go the Fuck to Sleep, which has been translated into 40 languages, and was Time Magazine's 2011 "Thing of the Year." The sequel, You Have to Fucking Eat, was published in November of 2014 and is also a New York Times bestseller.

Published on September 23, 2015 11:51

September 22, 2015

#Culture360: Black Women & Television, Serena Williams and that Apple Music Commercial

'A new season of television launches this week with the return hit shows Empire and Black-ish, notable for their showcasing narratives of black life in America. Meanwhile, Viola Davis won an Emmy this weekend for "Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series," becoming the first woman of color to win the award. In this edition of

#Culture360

WUNC's Frank Stasio talks Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and multimedia at St. Augustine University and Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African American Studies, and about Black Women & Television, Serena Williams and that Apple Music Commercial.'

'A new season of television launches this week with the return hit shows Empire and Black-ish, notable for their showcasing narratives of black life in America. Meanwhile, Viola Davis won an Emmy this weekend for "Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series," becoming the first woman of color to win the award. In this edition of

#Culture360

WUNC's Frank Stasio talks Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and multimedia at St. Augustine University and Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African American Studies, and about Black Women & Television, Serena Williams and that Apple Music Commercial.'

Published on September 22, 2015 20:42

Ahmed’s Clock, Banneker’s Clock, and the Racial Surveillance of Invention in America

Ahmed’s Clock, Banneker’s Clock, and the Racial Surveillance of Invention in America by Britt Rusert | @b_rusert | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Ahmed’s Clock, Banneker’s Clock, and the Racial Surveillance of Invention in America by Britt Rusert | @b_rusert | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)While 14-year-old Ahmed Mohamed’s clock and his arrest link to current histories of Islamophobia in the United States as well as to the politics of inclusion in the STEM fields, there are other parts of this story that tap into a much longer history of race and science. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins’ claim earlier this week that Ahmed’s clock was a “fraud” also reproduced a long history of the racial surveillance of invention itself in America.

In 1753, a young man of African descent named Benjamin Banneker also rose to prominence for building a clock: his creation was an impressive striking clock crafted out of wood. Banneker was a free man who gained regional and national recognition as an almanac-maker, astronomer, surveyor, and inventor in eighteenth-century America. He lived his entire life in Baltimore County, Maryland, where he farmed tobacco on a modest plot of land. Banneker constructed his clock when he was only 22 years old. In an age in which timepieces were still somewhat rare in the American colonies, visitors came from near and far to view a working clock constructed by a young man of color.

The story goes that Banneker entertained an almost constant stream of visitors in his home, people who wanted to see this homemade clock and were also curious about the black inventor who made it. But at the same time as Banneker was praised for his displays of intelligence and even genius, his inventions and scientific knowledge were also viewed with suspicion and disbelief by many white people. The barrage of visitors to Banneker’s home was thus also about confirming that this man, a black man, actually made the clock himself. And in this way, Banneker’s clock, like Ahmed’s clock, became a site of criminalization and racial surveillance.

One gets the sense that Banneker was forced to spend a lot of his time proving himself to whites: people from around the country sent him mathematical proofs to which they expected he would respond. After Thomas Jefferson wrote about the intellectual inferiorities of the African race in his book, Notes on the State of Virginia, Banneker sent a letter to the founding father, and then Secretary of State, in which he enclosed a manuscript copy of his own almanac for 1792. In Notes, Jefferson said that the jury was still out on the mental capacities of black people: he would need more proof to be convinced.

Banneker’s almanac stood as one such proof of the capabilities and capacities of the race. But Banneker was not just interested in proving the mental equality of Africans, he also used this as an opportunity to plead on behalf of his brethren, those men, women, and children who were unjustly held as slaves and captives in a supposedly freedom-loving republic.

When President Obama invited Ahmed to the White House last week, he also echoed Banneker’s story. Jefferson replied to Banneker’s letter with a curt, somewhat formulaic response, but one that nonetheless helped to legitimate Banneker’s scientific investigations and inventions on the national stage. He thanked Banneker for his letter and almanac and wrote, “No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit.” While Obama tweeted “Cool clock, Ahmed,” Jefferson’s language was ensconced in the formalities of Enlightenment rhetoric and letter writing. But there is much that connects these two pieces of correspondence, including the significance of a president, and in Jefferson’s case, a future president, recognizing the achievements and potential of inventors of color in the United States.

The use of Ahmed’s story to encourage young Muslims and other kids to get interested in engineering and other STEM fields is a laudable one, and one that will hopefully encourage future clock-makers, astronomers, and more. But this young man’s interest in inventing, experimenting, and even “tinkering” at home is also part of a vibrant history of race, science, and invention in the United States that exceeds both the classroom and presidential politics.

In the early nineteenth century, a handful of African Americans, from the revolutionary David Walker to the physician and pharmacist James McCune Smith, continued to carry on Benjamin Banneker’s legacy: they memorialized Banneker’s scientific achievements, wrote more critiques of Jefferson’s damaging theories of race, and produced sophisticated responses to an emerging racial science in the nineteenth century that abetted the slave system.

Largely restricted from universities, medical schools, and laboratories, they also worked on their own forms of autodidactic study and scientific experimentation, forms of invention and learning that were often explicitly linked to black freedom struggles against slavery in the South and anti-black racism in the North. These figures fought against the criminalization of African American experiments with science, but they also thought that science could be used to will a more equitable country into existence. In this way, we might say that Ahmed is continuing to carry that baton, linking scientific invention to the social movements of our own time.

+++

Britt Rusert is a Visiting Associate Research Scholar at Princeton University and an Assistant Professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She is completing a book titled “Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture.” Follow her on Twitter: @b_rusert

Published on September 22, 2015 20:20

September 21, 2015

Viola Davis, "White Lady Tears" & the Lives of Black Women

Viola Davis, “White Lady Tears” & the Lives of Black Womenby LaVonya Bennett | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Viola Davis, “White Lady Tears” & the Lives of Black Womenby LaVonya Bennett | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)“The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity.”-- Viola Davis

These frank and truthful words resounded loudly as Viola Davis became the first black woman to win best actress in a drama series on Sunday night’s Emmys. This was an epic moment in media and American history. This moment is also an educational opportunity on the realities faced by black women. In brief, there are three learning curves Davis’ speech will allow us to capitalize on.

First is understanding that the success of black women does not hinge on us figuratively dragging ourselves and others over a line. And, if it did, there are not many women of color in spaces to do the dragging. This is what happens when spaces focus on diversity instead of inclusion. Merely having a token representative does not change the harsh experiences women of color face in exclusive, white spaces.

However, it is not just a line that presents itself as a hurdle. Unlike the literal wall that leading Republican candidate, Donald Trump, wishes to build on the southern border, the systemic barriers faced by women of color cannot come crumbling down with explosives and a cleanup crew. The wall we experience is a systemic structure upheld by racism, patriarchy, and the privilege flaunted by Nancy Lee Grahn. (More on her in a moment.) This wall can only come down when people of power begin to go beyond diversity, creating equitable and inclusive spaces, engaging in privilege checking, and understanding that others experiences truly vary from their own. This consciousness is what begins to chip away at the systemic wall most women of color stand behind.

Second, Nancy Grahn was helpful in showing us that black women are not allowed to openly share their success, discuss their pains, and detail their experiences unless white folk ask us to educate them. After Davis made history, Grahn spewed her ignorance in twitterland with the divisive, un-acknowledging, racialized “all women” rhetoric, but was not prepared for the ‘clap back’ coming her way. She was not ready for the reality check coming, but she got it anyway.

Had she educated herself on all women like she stated in her twittersplaining of her white lady tears, she would have recognized that beauty standards are based on her likeness, in contrast to Viola Davis who had national articles written about her not meeting those beauty standards. Similarly, Grahn would know that the .79 cents to the dollar only looks at the pay of white women and she would recognize that roles in television are made for white women by white men and women. Her “all women” twitter rants only served to silence black women.

Lastly, when Davis stated, “You cannot win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there” she shed light on the limited number of roles to which women of color have access. As Davis works in and through patriarchal systems, we see that success in many realms is only afforded if men, particularly white men, want to create those spaces. Theoretically it would be nice to operate only in a system that was created for black women, but unfortunately we do not. And, until audiences begin to appreciate the unique experiences of black women, we never will.

White, heteronormative, male power structures make it impossible for women of color to reach back. The fatigue of simultaneously fighting multiple battles is psychologically exhausting and physically taxing.

The next time a woman of color tells you about her experiences, listen. The next time a woman of color tells you about her pain, believe her. The next time a woman of color educates you on the struggles she experiences, look at the systemic injustices that may not impact you as they do women of color. Do not silence us because you fear having to recognize your own privilege.

*Thank you Lawrence Ware for creating spaces for black women. I appreciate you!

+++

LaVonya Bennett is an Administrator in Residence Life, a division of Student Affairs, and an adjunct instructor at the University of Oklahoma. She serves as a Directorate member with the Coalition for Women's Identities through the American College Personnel Association. She can be reached at: Lavonyabennett@gmail.com

Published on September 21, 2015 20:53

Left of Black S6:E2: Choreographer + Dancer Camille A. Brown--Dance & The Stories Black Girls Tell

Left of Black S6:E2: Choreographer + Dancer Camille A. Brown--Dance and The Stories Black Girls Tell

Left of Black S6:E2: Choreographer + Dancer Camille A. Brown--Dance and The Stories Black Girls TellOn this episode of Left of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined via Skype by Camille A. Brown (@CamilleABrown) —Award Winning Dancer + Choreographer + founder of Camille A. Brown and Dancers.

Brown’s latest work Black Girl: Linguistic Play, “explores the broad spectrum of black female identity” through dance and storytelling. The World Premiere engagement of Black Girl: Linguistic Play is at the Joyce Theater in New York City, before it tours nationally.Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on September 21, 2015 18:03

September 20, 2015

Carrie Mae Weems: Diamonstein-Spielvogel Lecture at the National Gallery of Art

'For more than 30 years Carrie Mae Weems has made provocative, socially motivated art that examines issues of race, gender, and class inequality. Often producing serial or installation pieces, her conceptually layered work employs a variety of materials including photographs, text, fabric, sound, digital images, and most recently, video. For the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Lecture Series at the National Gallery of Art, Weems discusses her career and artistic process.'

'For more than 30 years Carrie Mae Weems has made provocative, socially motivated art that examines issues of race, gender, and class inequality. Often producing serial or installation pieces, her conceptually layered work employs a variety of materials including photographs, text, fabric, sound, digital images, and most recently, video. For the Diamonstein-Spielvogel Lecture Series at the National Gallery of Art, Weems discusses her career and artistic process.'

Published on September 20, 2015 19:05

The McCrary Sisters + The Fairfield Four: Living History with Two Gospel Quartets

Watch The McCrary Sisters and The Fairfield Four, two groups united by blood, as they combine to perform "Rock My Soul" in Texas. -- +NPR Music

Watch The McCrary Sisters and The Fairfield Four, two groups united by blood, as they combine to perform "Rock My Soul" in Texas. -- +NPR Music

Published on September 20, 2015 18:05

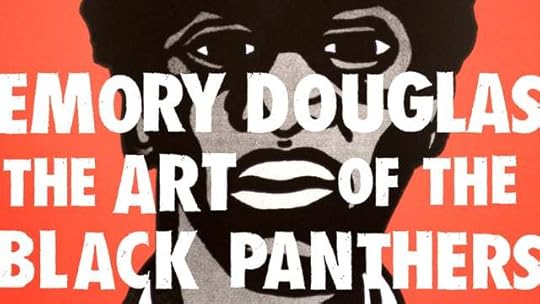

Emory Douglas: The Art of The Black Panthers (dir. Dress Code)

'Emory Douglas was the Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. Through archival footage and conversations with Emory we share his story, alongside the rise and fall of the Panthers. He used his art as a weapon in the Black Panther Party’s struggle for civil rights and today Emory continues to give a voice to the voiceless. His art and what The Panthers fought for are still as relevant as ever.'-- Produced and Directed by: Dress Code. Emory Douglas: The Art of The Black Panthers from Dress Code on Vimeo.

'Emory Douglas was the Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. Through archival footage and conversations with Emory we share his story, alongside the rise and fall of the Panthers. He used his art as a weapon in the Black Panther Party’s struggle for civil rights and today Emory continues to give a voice to the voiceless. His art and what The Panthers fought for are still as relevant as ever.'-- Produced and Directed by: Dress Code. Emory Douglas: The Art of The Black Panthers from Dress Code on Vimeo.

Published on September 20, 2015 10:09

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.