Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 646

February 5, 2016

#TheRemix: Why Some White Women Hate Affirmative Action

'James Braxton Peterson, host of #TheRemix talks with journalist Chloe Angyal, Senior Front Page Editor at

The Huffington Post

. Her recent article "Affirmative Action Is Great For White Women. So Why Do They Hate It?" looks at the ongoing debate about race and gender in affirmative action cases.'

'James Braxton Peterson, host of #TheRemix talks with journalist Chloe Angyal, Senior Front Page Editor at

The Huffington Post

. Her recent article "Affirmative Action Is Great For White Women. So Why Do They Hate It?" looks at the ongoing debate about race and gender in affirmative action cases.'

Published on February 05, 2016 04:40

Intersection: Fighting for Black Lives, in Flint and Beyond

'This Black History Month, we're thinking about racist violence and the people who fight against it.

Intersection

Host Jamil Smith explores three stories, and talks with Rebecca Leber, Chloe Angyal, Lisa Lindquist-Dorr, and Blair LM Kelley.'

'This Black History Month, we're thinking about racist violence and the people who fight against it.

Intersection

Host Jamil Smith explores three stories, and talks with Rebecca Leber, Chloe Angyal, Lisa Lindquist-Dorr, and Blair LM Kelley.'

Published on February 05, 2016 04:33

February 4, 2016

Soul Revolt: When Norman Whitfield Brought a Sonic Revolution to Motown

Norman Whitfield in the studio with The Undisputed TruthSoul Revolt: When Norman Whitfield Brought a Sonic Revolution to Motownby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Norman Whitfield in the studio with The Undisputed TruthSoul Revolt: When Norman Whitfield Brought a Sonic Revolution to Motownby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)At the root of Motown’s success in the 1960s was a stable of youthful and innovative producers and songwriters. Though figures like William “Smokey” Robinson and the trio of Brian Holland, Eddie Holland and Lamont Dozier are legendary for their roles in Motown’s rise as the “Sound of Young America,” Norman Whitfield, the fiery Harlem born producer, is often given short shrift. Whitfield, was arguably the most important of those first generation of Motown producers as he adeptly adapted the Motown sound, in the late 1960s, to fit the tenor of one of the most tumultuous political and cultural moments in American society. In the process, Whitfield put a lasting stamp, not just on Soul music, but pop music for years to come.

Norman Whitfield was, like most young Black Americans in the early 1960s, smitten by the sounds that emanated from Detroit’s Hitsville Studio, home to Motown Records. During that era Whitfield, then in his early twenties, could be found hanging around Hitsville and stalking Motown personnel, trying to gain entry into a world that was beginning to define what Andre Harrell would later term “High Negro Style.” Motown founder and President Berry Gordy made ample use of discerning youth listeners to test records slated for release.

Norman Whitfield’s first chance at Motown came as one of those testers and after getting some experience producing local acts, he was finally given the chance to produce some of Motown’s lower tier artists such as the Marvelettes (“Too Many Fish in the Sea”) and the Velvelettes (“Needle in a Haystack”). After earning Gordy’s trust on tracks like Marvin Gaye’s “Pride and Joy,” Whitfield was given the chance to produce The Temptations, the group he really wanted to work with.

“Girl (Why You Wanna Make Me Blue)” from 1964 is one of Whitfield’s early successes with the Temptation, but his opportunity to really craft a signature sound for the them came courtesy of the spirit of competition that pervaded Motown during its peak years. Because Gordy was committed to the financial bottom line, above all else, Motown functioned as a true meritocracy—at least for its flagship acts. At the foundation of that meritocracy was the label’s quality control unit, where Gordy’s most trusted ears would literally vote on the label’s releases.

Though Smokey Robinson had a major impact on the Temptations development as a crossover pop act, beginning with their breakthrough recording “The Way You Do the Things You Do” and including the group’s most recognizable song, “My Girl” (1964), he found himself in open competition with Whitfield to take the group to the next level.

Whitfield was promised by Gordy that if his “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” outperformed Robinson’s “Get Ready” on the pop charts he would become the group’s primary producer. Though “Get Ready” was a major hit on the black charts, it was “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” that scored for pop audiences. As Nelson George notes in Where Did Our Love Go?: The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound, The Temptations had become one of the cornerstones of Gordy’s crossover ambitions.

Though some black audiences had grown lukewarm towards Motown product, preferring the sounds wafting from Stax and later Muscle Shoals, Whitfield seemed to have a pulse on the changing dynamics of Soul music and pop music in general. And Whitfield delivered for Gordy with subsequent hits like “Beauty’s Only Skin Deep,” “I Know I’m Losing You,” “You’re My Everything” and “I Wish It Would Rain,” marking the highpoint of the classic Temptations’ formation that featured David Ruffin on lead vocals. During this period Whitfield also produced “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” which was the first major hit for Gladys Knight & the Pips.

With the subsequent departure of Ruffin from the Temptations and the import of Dennis Edwards as the new lead singer, Whitfield pushed the group into a new direction in 1968. Several factors influenced Whitfield’s move towards what some called Psychedelic Soul including the escalation of the Vietnam War, the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy within months of each other, racial violence in many of the nation’s major cities and the fractious Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

In this period Motown’s sweet harmonies were decidedly out of sync with the energy coming from the streets. Musically that energy could be heard in the songs of groups like Jefferson Airplane and within the genre of Soul, the emergent sounds of Sly & the Family Stone and the revamped Stax label, led by the innovative production of the late Isaac Hayes.

With the Temptations and Dennis Edwards serving as his muses Whitfield thought he could do it better. At the very least with the superior market reach of Motown, Whitfield was easily positioned to become the most visible purveyor of the new sound and such was the case when Whitfield went into the studio with the Temptations to record “Cloud Nine.” Though much has been made about the song’s meaning—Whitfield’s longtime musical partner Barrett Strong penned the lyrics—as Motown coyly denied that the song celebrated drug use, it was Whitfield’s production that was the most striking feature. “Cloud Nine” earned The Temptations their first Grammy Award and with the departure of Holland-Dozier-Holland from the fold, Whitfield had free reign to craft Motown’s sound as it pushed boldly into the future.

That same year, Whitfield revamped “I Heard Through the Grapevine” for Marvin Gaye, producing a track that was more sinister than Gladys Knight and the Pips’ frenzied church version. The song would become one of the label’s best selling singles. Whitfield also followed with “Psychedelic Shack” and “Ball of Confusion” with the Temptations and the influence of Whitfield could be heard in the work on Motown producers like Fonce Mizell, Freddie Perren and Frank Wilson.

Whitfield found success, in part, because he never gave up on the classic Motown hooks, despite all of the psychedelic cacophony that accompanied his post 1968 Motown productions. Whitfield also was deft and nuanced in the ways he borrowed from his competition. One great example is Edwin Starr’s “War.” The song begins with a rolling drum, not unlike that which opens Sly and The Family Stone’s signature recording “Stand” but whereas the lyrics to Stone’s track offers innocuous platitudes, Starr’s “War,” courtesy of Strong’s lyric with its anti-war theme, identifies a clear cut issue to stand for.

Despite Whitfield’s success, several acts grated against his production sensibilities. Marvin Gaye famously almost came to blows with Whitfield when the latter pushed him to sing in a higher register. The Temptations had long felt the uniqueness of their harmonic style was secondary to Whitfield’s production, a fact borne out in the number of Motown acts that did multiple versions of Whitfield songs. As the battles became more contentious, Whitfield provided the group with one last homage to the glory of their early years with “Just My Imagination,” which ironically remains one of Whitfield’s most memorable productions.

Perhaps in response to the tensions with The Temptations, Whitfield helped assemble the group Undisputed Truth, whose sessions became a repository for Whitfield’s most experimental music. The group’s only major hit was “Smiling Faces,” (1971) released a year before Whitfield and the Temptations collaborated for one of the group’s most memorable performances, “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.”

After Whitfield split from Motown in 1973 he formed Whitfield Records taking Undisputed Truth and Rose Royce with him. The latter group initially served as the backing band for Edwin Starr, but ultimately became Whitfield’s last great success largely on the strength of their work on the soundtrack recording for the film Car Wash which included signature tracks like “I Wanna Get Next to You,” “I’m Going Down,” (later a hit for Mary J. Blige) and the title track.

Whitfield and writing partner Barrett Strong were inducted into The Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2004.

Published on February 04, 2016 17:07

February 3, 2016

Left of Black S6:E16: When SNCC was the Black Lives Matter of the Civil Rights Movement

Left of Black S6:E16: When SNCC was the Black Lives Matter of the Civil Rights Movement

Left of Black S6:E16: When SNCC was the Black Lives Matter of the Civil Rights MovementLeft of Black host and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in studio by Judy Richardson and Charlie Cobb, Jr., veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and visiting activist scholars for The SNCC Digital Gateway Project.

Richardson is a film producer, whose credits include the groundbreaking Eyes on the Prize (I + II) and the 1994 Emmy and Peabody Award-winning documentary, Malcolm X: Make It Plain. She is also the coeditor, with five other SNCC women, of Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts By Women in SNCC. Cobb is a longtime journalist, who offered some of the first reporting on Africa for National Public Radio in the 1970s, and later worked on the editorial staff at National Geographic Magazine. He is the author of This Nonviolent Stuff′ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible. Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in conjunction with the Center for Arts, Digital Culture & Entrepreneurship (CADCE).

***

Episodes of Left of Black are also available for free download in @ iTunes U

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on February 03, 2016 11:01

Between a Surrogate & a Critic: Michael Eric Dyson Talks 'The Black Presidency'

'In Michael Eric Dyson’s rich and nuanced book new book,

The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America

, Dyson writes with passion and understanding about Barack Obama’s “sad and disappointing” performance regarding race and black concerns in his two terms in office. While race has defined his tenure, Obama has been “reluctant to take charge” and speak out candidly about the nation’s racial woes, determined to remain “not a black leader but a leader who is black.” Dyson cogently examines Obama’s speeches and statements on race, from his first presidential campaign through recent events—e.g., the Ferguson riots and the eulogy for the Rev. Clementa Pinckney in Charleston—noting that the president is careful not to raise the ire of whites and often chastises blacks for their moral failings.' +KirkusReviews

'In Michael Eric Dyson’s rich and nuanced book new book,

The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America

, Dyson writes with passion and understanding about Barack Obama’s “sad and disappointing” performance regarding race and black concerns in his two terms in office. While race has defined his tenure, Obama has been “reluctant to take charge” and speak out candidly about the nation’s racial woes, determined to remain “not a black leader but a leader who is black.” Dyson cogently examines Obama’s speeches and statements on race, from his first presidential campaign through recent events—e.g., the Ferguson riots and the eulogy for the Rev. Clementa Pinckney in Charleston—noting that the president is careful not to raise the ire of whites and often chastises blacks for their moral failings.' +KirkusReviews

Published on February 03, 2016 04:33

February 2, 2016

"Don't call it Jazz...It's Social Music"--Trailer for 'Miles Ahead' (dir. Don Cheadle)

Published on February 02, 2016 20:44

Director Dawn Porter Discusses Trapped--New Film About Reproductive Health in the Deep South

'RBTV caught up with filmmaker Dawn Porter (Gideon's Army) at THe ARRAY Soiree at Sundance 2016, where she was prepping for the world Premiere of Trapped, her latest documentary which ultimately won the U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award for For Social Impact Filmmaking.' --

ReelBlack

'RBTV caught up with filmmaker Dawn Porter (Gideon's Army) at THe ARRAY Soiree at Sundance 2016, where she was prepping for the world Premiere of Trapped, her latest documentary which ultimately won the U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award for For Social Impact Filmmaking.' --

ReelBlack

Published on February 02, 2016 17:38

Moral Panics & Mass Incarceration in the Neoliberal City: Katrina After 10

"Katrina After Ten” brought together activists, artists, and intellectuals to discuss critical issues such as environmental racism, gender discrimination, gentrification, mass incarceration, education and privatization; as well as the history and future of social movements in New Orleans. Moral Panics & Mass Incarceration in the Neoliberal City: • Jordan T. Camp, Postdoctoral Fellow, CSREA and Watson Institute, Brown University • Malcolm Suber, New Orleans community activist, founding member of People's Hurricane Relief Fund • Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, Ph.D. Candidate in Geography, CUNY Graduate Center.

"Katrina After Ten” brought together activists, artists, and intellectuals to discuss critical issues such as environmental racism, gender discrimination, gentrification, mass incarceration, education and privatization; as well as the history and future of social movements in New Orleans. Moral Panics & Mass Incarceration in the Neoliberal City: • Jordan T. Camp, Postdoctoral Fellow, CSREA and Watson Institute, Brown University • Malcolm Suber, New Orleans community activist, founding member of People's Hurricane Relief Fund • Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, Ph.D. Candidate in Geography, CUNY Graduate Center.

Published on February 02, 2016 17:25

BK Stories: Ending Gun Violence and Police Brutality in Brooklyn: Part 3

'In the final part of our three part series on Gun Violence in Brooklyn, we get an inside look into how organizations on the ground in Brooklyn are dealing with gun violence, crime, gun control, and the NYPD in suffering neighborhoods.' +BRIC TV

'In the final part of our three part series on Gun Violence in Brooklyn, we get an inside look into how organizations on the ground in Brooklyn are dealing with gun violence, crime, gun control, and the NYPD in suffering neighborhoods.' +BRIC TV

Published on February 02, 2016 17:19

February 1, 2016

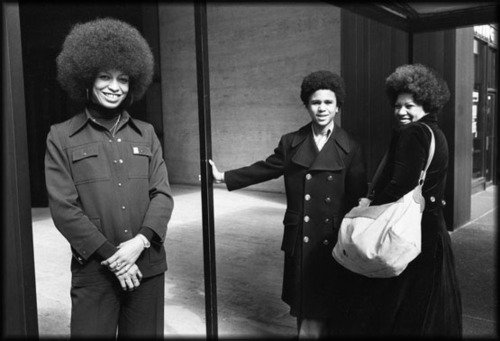

Toni Morrison + Angela Davis Talk Frederick Douglas + Education + Liberation

Pulitzer and Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison + activist and author Angela Davis, in a wide-ranging talk on Frederick Douglass, education, and liberation, recorded in 2010 at the New York Public Library.

Pulitzer and Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison + activist and author Angela Davis, in a wide-ranging talk on Frederick Douglass, education, and liberation, recorded in 2010 at the New York Public Library.

Published on February 01, 2016 16:37

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.