Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 634

March 18, 2016

Marc Lamont Hill Discusses 3 Elements Underpinning Education Reform

'What are some of the essential elements that should underpin our approach to educating children? Writer and educator Kiese Laymon suggests thee important factors—good love, healthy choices and second chances—that are becoming guiding principles for education reformers. In this video clip, Dr. Marc Lamont Hill, a professor of African American Studies at Morehouse College, discusses the application of Laymon’s principles to educating our children.' -- +NewsOne Your browser does not support iframes.

'What are some of the essential elements that should underpin our approach to educating children? Writer and educator Kiese Laymon suggests thee important factors—good love, healthy choices and second chances—that are becoming guiding principles for education reformers. In this video clip, Dr. Marc Lamont Hill, a professor of African American Studies at Morehouse College, discusses the application of Laymon’s principles to educating our children.' -- +NewsOne Your browser does not support iframes.

Published on March 18, 2016 10:01

March 17, 2016

A Fallen Black Girl: Remembering Latasha Harlins

A Fallen Black Girl: Remembering Latasha Harlins 25 Years Laterby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | The Root

A Fallen Black Girl: Remembering Latasha Harlins 25 Years Laterby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | The RootLatasha Harlins would not live long enough to witness the birth of Twitter or the era of the hashtag. Yet it’s difficult not to summon her name—or her story—amid hashtag memorials for other dead black girls, like 19-year-old Renisha McBride and Sandra Bland.

Latasha, age 15, was shot in the back of her head by grocery-store owner Soon Ja Du two weeks after the infamous Rodney King beating in 1991. It happened during a dispute at Du’s South-Central Los Angeles store and ended with Latasha lying dead on the ground with a $1.79 bottle of orange juice sitting on the counter and two crumpled dollar bills in her hand. The memory of Latasha’s shooting eerily haunts the present as we confront the recent death of McBride, whose shooter claims self-defense.

As UCLA historian Brenda Stevenson observes in her book, The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the LA Riots, much about Latasha’s life and death is all too familiar. As Du testified during her murder trial, in Latasha she didn’t see a black girl who loved BBD—the around-the-way girl with the “New Edition Bobby Brown button” on her sleeve that LL Cool J once lovingly observed. Rather, per Du’s teenage son, what she saw instead was a “gang member.”

Latasha’s sartorial choices—described by a friend in Stevenson’s book as “blue dickies, a white T-shirt, and a black hoodie, always the black hoodie”—reflected her desire, no doubt, to simply fit in. As another friend of hers recalled, “Tasha was just very quiet and shy ... And she was hard, you could tell. You didn’t mess with her. She was like in her own world.” None of which suggests that she deserved to die on a Saturday morning in a grocery store doubling as a liquor store, in her own neighborhood.

It is conventional wisdom that the dramatic deaths of black women and girls simply don’t inspire the spirit of agitation that many might recall in the invocation of the names “Emmett Till” or “Trayvon Martin.” And to be sure, we’d be hard-pressed to think of a black woman or girl who resonates in our collective psyche the way Emmett and Trayvon do.

Emmett and Trayvon were middle-class boys who we believed would become solid citizens, so it wouldn’t be surprising if Latasha might be forgotten in the shadow of the case in which four L.A. police officers were acquitted of beating Rodney King. Yet Latasha became the catalyst for the most sustained example of black rage since the Watts insurrections of 1965.

Stevenson reminds us that when the phrase “No justice, no peace!” became the anthem of the insurrections that set Los Angeles afire in April of 1992, “Rodney King was not the symbol of injustice that catalyzed the protest: Latasha Harlins was. Indeed the uprising’s slogan ... was chanted by protesters at the Empire Liquor Market immediately after Latasha was killed, a full year before ... ”

How, then, was it that the death of this 15-year-old black girl was able to inspire the level of collective response that she did? The answer perhaps lies in the fact that Latasha’s murder, despite our collective memories about anti-black violence, was a rarity.

Given that the vast majority of homicides occur within a single racial group, and the majority of females are killed by males, Stevenson notes, “Harlins’ death at the hands of Du was quite unusual. Harlins’ shooting challenged the Black-White divide that often accompanies narratives of anti-Black violence. Du was not only Korean born, but also a woman, as was Judge [Joyce] Karlin, who presided over Du’s trial, and eventually sentenced her to ‘no further jail time.’ ”

Equally rare, according to Stevenson, was that at the time, homicides of black girls in Latasha’s age group (14 to 17) represented less than .01 percent of the murder rate in 1991. That we know so well, today, the examples of Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Hadiya Pendleton and Renisha McBride—during an era when, overall, black-youth homicides have declined since the late 1980s—speaks volumes about the surreal nature of their deaths as well as our ability to access and share information about such violence.

The public’s access to the footage, before the days of widespread Internet access, gave Latasha’s shooting and the King beating a sense of immediacy that was akin to what was experienced by the generation that first saw Emmett Till’s bloated and mutilated body in the pages of Jet magazine in 1955. Videos of both events circulated on local and national news broadcasts in ways that carried the same gravity of the televised images of young civil rights activists being hosed on Southern streets. As then-Deputy District Attorney Roxane Carvajal asserted before the opening of Du’s trial, “This is not television. This is not the movies. This is real life ... You will see Latasha being killed. She will die in front of your eyes,” her comments anticipating reality television—MTV’s The Real World launched weeks after the so-called L.A. Riots—and social media.

It can be argued that our immediate access to these images of anti-black violence has desensitized us to such violence, and such arguments have long been made about the violence that some witness every day in their communities, whether in the Middle East or Chicago. Social media has also allowed us to take the everyday micro-aggressions that we have long survived—and have created playful strategies to resist—and to elevate those strategies to digital protests.

It can be argued that our immediate access to these images of anti-black violence has desensitized us to such violence, and such arguments have long been made about the violence that some witness every day in their communities, whether in the Middle East or Chicago. Social media has also allowed us to take the everyday micro-aggressions that we have long survived—and have created playful strategies to resist—and to elevate those strategies to digital protests.

Yet much remains the same. As Stevenson writes, “Judge Karlin and Soon Ja Du ... shared similar ideals about appropriate gender behavior for females, and those ideals excluded Latasha.” Although the images of black women and girls circulate in radically different ways than they did 20 years ago—in no small part because of the role of corporate media in overrepresenting and distorting the pathologies of black life—there remains little space for black girls to be children and black women to be ... human. In this regard, it is conceivable that Soon Ja Du saw Latasha Harlins no more clearly than Theodore Paul Wafer would see Renisha McBride two decades later.

Published on March 17, 2016 19:49

#WUNCBackChannel: The Color And Character Of Hollywood After #OscarsSoWhite

Comedian Chris Rock hosted the Oscars amid controversy around the awards' lack of diversity. But controversy around race in Hollywood continued after Rock's performance. On this episode of #WUNCBackChannel host Frank Stasio talks with Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and broadcast media at St. Augustine's University, and Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African American Studies + English at Duke University, about the way the stories of African American icons are told. Bullock Brown and Neal discuss Nina, Miles Ahead, Race and Zootopia.

Comedian Chris Rock hosted the Oscars amid controversy around the awards' lack of diversity. But controversy around race in Hollywood continued after Rock's performance. On this episode of #WUNCBackChannel host Frank Stasio talks with Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and broadcast media at St. Augustine's University, and Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African American Studies + English at Duke University, about the way the stories of African American icons are told. Bullock Brown and Neal discuss Nina, Miles Ahead, Race and Zootopia.

Published on March 17, 2016 14:37

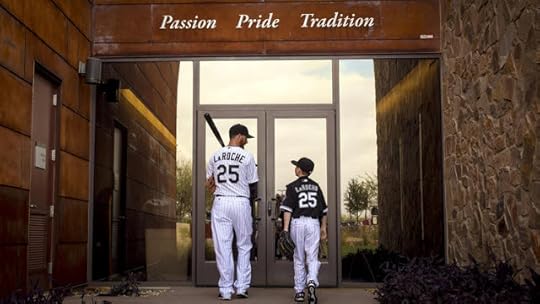

#FamilyFirst? Adam LaRoche's First World Dilemma

Photo Credit: Brian Cassella #FamilyFirst? Adam LaRoche's First World Dilemma by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Photo Credit: Brian Cassella #FamilyFirst? Adam LaRoche's First World Dilemma by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)When 12-year Major League Baseball veteran Adam LaRoche announced his retirement, citing the desire of his employers--The Chicago White Sox--to limit the time his 14-year-old son spent in the clubhouse, I, too, felt a tugging at the heartstrings. But before we coronate LaRoche as the new icon of a so-called #FamilyFirst movement, let’s be clear that his “sacrifice” is borne of a level of privilege and wealth that most Americans simply do not have access to.

As a parent who prides himself on being both accessible to my daughters and engaged in all facets of their lives, it is always great to hear of parents, particularly fathers, who try to design their professional lives in a manner to maximize time with their children. Indeed there’s been a long tradition in Major League Baseball of the sons of players serving as bat boys. Hall of Famer and “Iron Man” Cal Ripken, Jr. served as bat boy when his father was a coach for the Baltimore Orioles in the 1970s, though Darren Baker, son of Washington Nationals’ manager Dusty Baker, might be the the most famous. Baker’s presence as a bat boy at age 3 in 2002 raised eyebrows when he avoided being run over at home plate during the 2002 World Series.

The LaRoche story has generated traction, in part, because of reports that he will be forgoing the final year of a two-year contract he signed last year, that would pay him $13 Million in base salary in 2016. However laudable LaRoche’s decision, the fact of the matter is that after a relatively long professional career, he likely had the financial stability to walk away from $13.

Most Americans lack such financial stability, let alone the ability to give up gainful employment.

The case of single mothers, particularly Black and Latina mothers, is instructive. Not only is staying at home to be with their young children not an option, such women are actively demeaned by the State and pundits when they choose to do so with the assistance of the State. Alternatively when single mothers choose to work--often earning depressed wages--they are often forced to bring young children to work with them because of the exorbitant cost of child care. Ironically when many of these mothers are unable to physically provide the level of care and attentiveness to their children--that those with privilege and money take for granted--they are castigated as being “bad” mothers.

LaRoche’s story might also resonate differently for some African-Americans, who remember when Black children had no choice but to work alongside their parents in the Jim Crow South, because they were valued by planters and landowners for their labor; their childhood denied.

Indeed there was a certain level of resistance conveyed within Jim Crow for those Black men, who had the financial stability to allow their children and wives to leave the field. Such men and women were rarely thought of as heroes, but rather as targets of White vigilantes who saw such Black families as threats to a racist social order.

Again, I am happy for the LaRoche family, but let’s not over celebrate a decision that is the byproduct of wealth and privilege, in a society where so many others can’t afford to put #FamilyFirst.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is Professor of African + African American Studies and Professor of English as Duke University. Neal is the host of the video podcast Left of Black. Follow him on Twitter at @NewBlackMan.

Published on March 17, 2016 12:16

Sonics + Visuals: 'This One's For Me & You"--Johnny Gill feat New Edition

Published on March 17, 2016 04:34

March 16, 2016

Edge of Sports: Harry Edwards on Disbanding the NCAA + Stopping The Madness of March

'Dr. Harry Edwards, renowned sports sociologist and author of the seminal text The Revolt of the Black Athlete joins host Dave Zirin on Edge of Sports. Dr. Edwards prescribes a stringent tonic for the NCAA’s ills: a complete dissolution and ground-up reformation focused on academics and athlete equity.'

'Dr. Harry Edwards, renowned sports sociologist and author of the seminal text The Revolt of the Black Athlete joins host Dave Zirin on Edge of Sports. Dr. Edwards prescribes a stringent tonic for the NCAA’s ills: a complete dissolution and ground-up reformation focused on academics and athlete equity.'

Published on March 16, 2016 15:55

Ice Cube and Common Talk Squashing Their Beef + Barbershop: The Next Cut

'Before the days of Twitter fingers and memes, rap beef was fought on wax. When Common released his instant-classic 1994 track "I Used to Love H.E.R.," a few lyrics seemingly took a dig at the rise of gangster rap which didn't sit well with West Coast gangsta rapper Ice Cube. In retaliation, Cube connected with Mack 10 and Westside Connection on the diss track "Westside Slaughterhouse." Now, over two decades later, the two have teamed up on the upcoming track "Real People" and the third installment in the Barbershop franchise, Barbershop: The Next Cut.'-- +Complex

'Before the days of Twitter fingers and memes, rap beef was fought on wax. When Common released his instant-classic 1994 track "I Used to Love H.E.R.," a few lyrics seemingly took a dig at the rise of gangster rap which didn't sit well with West Coast gangsta rapper Ice Cube. In retaliation, Cube connected with Mack 10 and Westside Connection on the diss track "Westside Slaughterhouse." Now, over two decades later, the two have teamed up on the upcoming track "Real People" and the third installment in the Barbershop franchise, Barbershop: The Next Cut.'-- +Complex

Published on March 16, 2016 15:43

Islam as Black History

'A conversation with Edward Curtis and Jamillah Karim around questions about Islam as Black History and why is it important to integrate the study of Black history and Islam. How does the study of gender challenge both Islamic and Black history? What role does Africa play in Islamic history? Why is it important for U.S. Muslims to study Black history?' +FranklinCenterAtDuke

'A conversation with Edward Curtis and Jamillah Karim around questions about Islam as Black History and why is it important to integrate the study of Black history and Islam. How does the study of gender challenge both Islamic and Black history? What role does Africa play in Islamic history? Why is it important for U.S. Muslims to study Black history?' +FranklinCenterAtDuke

Published on March 16, 2016 15:31

Tell Donald Trump I Said “Thank You” by Law Ware

Tell Donald Trump I Said “Thank You”by Law Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Tell Donald Trump I Said “Thank You”by Law Ware | @Law_Ware | NewBlackMan (in Exile)It is inevitable. Donald Trump will have the most GOP delegates going into the convention in July. The question now is relatively simple: what should you, the republican leadership, do going forward?

Listen. I don't have a dog in this fight. I'm a democrat, a progressive, a black man. You don't give a damn about me. If you had your way, you'd probably try to keep me from voting. Yet, I have a deep and abiding love of democracy. I'd like to see the process work as it should. So...let me offer you two suggestions on how to navigate this disaster you, yourself, devised.

1. Abandon all talk of a brokered convention. Just stop it. For the past few months there has been escalating violence at Trump rallies. His supporters are violently angry. How do you think they will respond if you nullify their choice? This is a climate you cultivated, fear and anxiety you provoked. The people have spoken. Respect their choice.

2. In the future, realize that when one stokes the fire of white supremacy, you unleash something that has the ability to harm you as well. Dog whistle politics, southern strategies, and veiled racism may get you passionate followers willing to vote against their interests—but that energy can turn ugly when a person like Trump comes along and says publicly what voters have been saying privately. Trump and his supporters do not surprise black folks in America.

It's white people that are flabbergasted by the vitriol and hatred. We have survived, nay thrived, in a white supremacist country, culture, and political climate our entire lives. Some of us are taken aback that people are now saying openly what we know has been said behind closed doors. A few of us were lulled to sleep by visions of Obamas in the White House and dreams of capitalistic gain, but we woke now—and we will #StayWoke.

Yet, to that end, I’d like it if you could convey to Donald Trump my following words of heartfelt appreciation:

Thank you for cutting the grass with your rhetoric so that now the snakes can no longer hide. Thank you for smoking out the black folks who, like Stephen in Django Unchained, are opportunists and willing to participate in white supremacy for time on CNN and an opportunity for financial gain.

Thank you for showing us the true nature of white preachers like Joel Osteen and Paula White who have innumerable black followers, but articulate a gospel grounded in prosperity and white supremacist understandings of Christianity.

Thank you for showing liberal white Americans that white supremacy is so pervasive and destructive that a mere discussion of class inequality is insufficient to address the racism seething just beneath the surface of American life. (Someone please get this information to Bernie Sanders and his uncritical supporters.) Finally, thank you for reminding black Americans that we are living in neither a post-racial nor a post-racist world. Many needed that desperately. Thank you. Sincerely.

Good luck, ladies and gentlemen. I can’t wait to see how you handle the convention in July. Like Michael Jackson eating popcorn at the beginning of Thriller, I’ll be watching with tiptoe anticipation.

+++

Lawrence Ware is an Oklahoma State University Division of Institutional Diversity Fellow. He teaches in OSU's philosophy department and is the Diversity Coordinator for its Ethics Center. A frequent contributor to the publication The Democratic Left and contributing editor of the progressive publication RS: The Religious Left, he has also been a commentator on race and politics for the Huffington Post Live, NPR's Talk of the Nation, and PRI’s Flashpoint. Follow him on Twitter: @law_ware

Published on March 16, 2016 08:03

Emma Dabiri: Black Hair is Finally Fashionable...But on Whose Terms?

'Growing up with afro hair can be traumatic, especially when white ideals of beauty are everywhere. But, says Scholar Emma Dabiri, black women are increasingly letting their natural hair out, and the ‘fro is becoming fashionable. But, she also argues, they are still too often measuring their beauty by the yardstick of whiteness.' -- +The Guardian

'Growing up with afro hair can be traumatic, especially when white ideals of beauty are everywhere. But, says Scholar Emma Dabiri, black women are increasingly letting their natural hair out, and the ‘fro is becoming fashionable. But, she also argues, they are still too often measuring their beauty by the yardstick of whiteness.' -- +The Guardian

Published on March 16, 2016 04:58

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.