Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 506

July 14, 2017

A Classic Revisited: a review of Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop

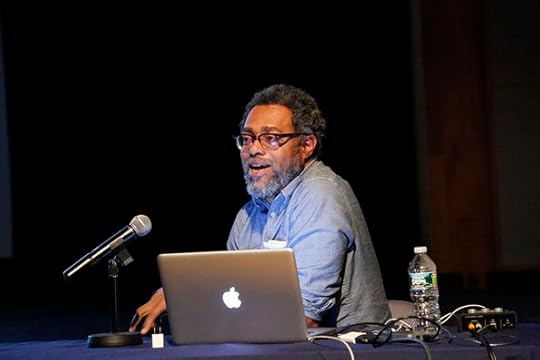

A Classic Revisited: a review of Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hopby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

A Classic Revisited: a review of Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hopby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)The work of late Eileen Southern and Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) are the twin pillars of Black Music scholarship in the United States. Trained as a musicologist, Southern was most well known for her classic study The Music of Black Americans: A History. Baraka, of course, is the author of the groundbreaking Blues People, a book that 50 years after its publication is generally recognized as the foundation of African-American Cultural Studies. Whereas Southern may have been most concerned with the music, Baraka was most concerned with the music’s political connotations, specifically in the context of Black Cultural Nationalism in the 1960s.

It is this seeming divide that Guthrie P. Ramsey largely recovers in his book Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop (University of California Press, 2003) An ambitious effort, Ramsey’s Race Music is an interdisciplinary explosion, finding grounding in the amorphous, theoretical and familial aspects of Black life and culture or what he refers to as the “Afro-modernist” impulse.

“For African Americans,” Ramsey argues, “the thrust of Afro-modernism has always been…defined primarily within sociopolitical arena: as the quest for liberation, freedom, and literacy as well as the seeking of upward mobility and enlarged possibilities within the American capitalist system.” (106) Given these desires there was quite a bit of importance attached to forms of Black expressive culture that entered into the mainstream of American culture in the early decades of the 20th century. Black literature, art, and music were perceived as vehicles to counteract racist constructs of Black culture and identity emanating from popular science journals, the burgeoning film industry and the advertising industry.

For many Black elites, most notably W.E.B. Du Bois, this was translated as putting forth the best “face” of the race. Ramsey’s use of the post-world war II period as a point of entry into his study is useful because the war provided an urgency to Black political demands for fair treatment and also marks a definitive break—generationally, culturally, aesthetically, socially and geographically—from the sanctioned face of Black expressive culture in the 20th century, at least as forwarded by Black cultural gatekeepers.

Specifically Ramsey links Afro-modernism to the “heady momentum of sociopolitical progress during the first half of the twentieth century, and the changing sense of what constituted African American culture (and even American culture generally speaking) at the postwar moment.” (28) Echoing the oft-cited work of Robin D.G. Kelley and Eric Lott, Ramsey locates a dramatic tension in the post-world war II period. Instead of privileging the work of be-bop artists, as Kelley and Lott do in their seminal essays, Ramsey suggests that the musical styles of mid-century blues figures like Louis Jordan, Cootie Williams and Dinah Washington—styles that would have been targeted and disparaged by some “Negro” gatekeepers before the war—became central tenets of the developing Afro-modern world.

For example, Ramsey sees a recording like “It’s Just the Blues” (1945) by the Four Jumps of Jive as “drenched in Afro-modernist sensibilities. The recording codified a specific moment or urbanity for African Americans. Even the ‘commercialism’ of the piece is suggestive of the aggressively new economic clout of African Americans, particularly those who lived in the urban north.” (51)

Though Ramsey’s definition of Afro-modernism fits into the interpretive framework of Baraka’s Blues People, Ramsey deftly roots this impulse within the intimacy of Black family life. Thus Race Music begins with Ramsey discussing the role of music in his family. As he writes in opening chapter, the autobiographical impulse throughout Race Music, “brings into high relief, some of the theoretical and intellectual points that I will explore throughout the book. As an African American scholar and musician, I believe there is value in exploring the historical grounding of my own musical profile and revealing this to readers.” (4) As such, “Daddy’s Second Line”—a reference to the death of Ramsey’s father and New Orleans styled funeral rituals—takes on an added significance.

Ramsey’s recollection of his father’s funeral (occurring at a time when he was finishing his dissertation) and the centrality of music in his family’s collective mourning process comprise what he refers to as “community theaters”—“sites of cultural memory” that “include but are not limited to cinema, family narratives and histories, the church, the social dance, the nightclub, the skating rink, and even literature.” (4)

In this regard, Ramsey’s work owes a great deal to that of early Birmingham School cultural theorists like Raymond Williams, who found value in the study of everyday life. While so much of African-American Cultural Studies has focused on the “everyday” spectacle—think here of virtually every scholarly study of hip-hop music and culture—Ramsey brings his analysis back to the more mundane aspects of everyday Black life. In other words how do Black people and Black families use Black music to cope with the everyday realities of Black life in the United States?

Like the industry term “race records,” which supposedly marked racial segregation in American listening practices, Ramsey’s Race Music privileges practices in which the Black masses used the very logic of racial segregation to create moments of catharsis, recovery and pleasure. Not simply relying on his own cultural memories, Ramsey devotes an entire chapter to the “community theater” of his extended family. For example, a song like Ray Charles’s “Night Time is the Right Time” can be read as a metaphor for the ways that some Blacks used late night leisure spaces—dancehalls, theaters, after-hours clubs and various other chitlin’ circuit entities—as a means of recovering their humanity in the face of 60-hour work weeks doing arduous and debilitating labor.

The ability of these leisure seekers to transcend their daily routines by finding some semblance of freedom on the dancefloor or listening to the riffs of an organ-sax R&B combo is an example of the kinds of catharsis that Ramsey locates within “community theater”. Ramsey’s argument about the centrality of community theaters to the study of Black life and culture is most compelling in chapter six (“‘Goin’ to Chicago”: Memories, Histories, and a Little Bit of Soul”), the book’s strongest chapter. In many ways the chapter, which examines three distinct community theaters, synthesizes the book’s often disparate and competing energies.

Ramsey notes that the “subjugated knowledge”—that which can be found in community theater—that he theorizes “represents a particular work of the imagination or collective memory of a specific family. These memories embody a cultural sensibility that should be a factor in the interpretation of African American music from this period and beyond.” (94) In addition to the communal memories of the “kin folk”, Ramsey also cites the scholarly discourses of “Blackness” that emerged in the 1960s (of which Southern’s work figures prominently) and the music itself. In this latter arena, Ramsey specifically, cites James Brown’s “Say It Loud” (1968) as “emblematic of [that] era’s new expression of Black pride.” (151) He further argues that Brown, as an artist, “stood at the crossroads between the Civil Rights and Black Power movements” and “between the celebration of Black sensuality and wholesome, Afro-styled family values.” (151)

Like Brown, Southern also negotiated between spaces, notably the ‘whiteness” of the academy and the hyper-Blackness of the Black Arts Movement and the patriarchy that manifested itself in both spaces. In many regards Southern’s ability to negotiate those spaces is emblematic of the very spaces that Ramsey negotiates throughout his book. Many of the intricate claims that Ramsey makes about the importance of community theater could not have been made without the import of Cultural Studies (I’m including Baraka in this) onto the field of Black music studies, but throughout Race Music Ramsey maintains an attention to musical detail, which was the hallmark of Southern’s work.

Ramsey’s study could have legitimately ended with chapter 6, but he relates his thesis to contemporary Black popular music forms or more generally the post-industrial moment. Though “Scoring a Black Nation: Music, Film, and Identity in the Age of Hip-Hop” (chapter 7) and “‘Santa Claus Ain’t Got Nothing on This!’: Hip-Hop Hybridity and the Black Church Muse” (chapter 8) seem like an obligatory attempt to make Race Music relevant to Hip-hop era scholarship, both chapters offer valuable insight in their own right as stand-alone essays. Ramsey finds value in the music of gospel artists like Kirk Franklin and Karen Clark-Sheard, whose abilities at “mixing and matching musical genres with distinct histories” allow them to “powerfully critique currents idea about secularism, sacredness and the intense commercialism that is part and parcel of hip-hop culture.” (215)

While the Black church has been an important site for the constitution of community within Black communities, it has been increasingly at odds with the decidedly secular and profane nature of Black expressive culture in the post-Civil Rights era. Artists like Clark-Sheard, Franklin and others like Mary Mary and Tonex have sought to collapse the largely generational divide, by providing the context in which the secular sensibilities of hip-hop could be “churched.”

Maintaining the spirit of community that pervades the book, Ramsey presents a unique vantage point to access Hip-hop’s relationship to the genres of Black music developed before it. Ramsey looks specifically at Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood (films powerfully linked to hip-hop’s move into the mainstream in the late 1980s and early 1990s) and Theodore Witcher’s Love Jones (loosely aligned to the Neo-soul moment of the late 1990s). Throughout the three films, Ramsey notes that “music is linked to other Black cultural practices such as the dozens, dance, card playing, and so on. Music is central to constructing Black characters within these films’ narratives.” (186)

Rather than seeing Hip-hop era film and popular music as being out of sync with the very notions of “community” that Black popular music has often constructed, Ramsey brings “Hip-Hop” back into the family fold. Ramsey’s take here is refreshing given that so much of the logic within Hip-Hop studies either consciously or unwittingly aims to establish Hip-Hop in isolation of genres of popular Black music that emerged before it.

As a working jazz musician and former musical director for a church, Guthrie Ramsey has a first-hand perspective on the intimacy between the music and the folk. As an interdisciplinary scholar trained as an ethnomusicologist he is also cognizant of the music and the formal academic modes of its study. The great success of Race Music is that Ramsey never loses sight of either of these worlds and that fact alone makes Race Music a groundbreaking addition to the fields of Ethnomusicology and African-American Studies.

+++

Originally published in ECHO: A Music Centered Journal (2005)

Published on July 14, 2017 16:10

July 13, 2017

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka On The 1967 Riots

Amiri Baraka | Neal Boenzi/The New York Times 'On July 12, 1967, a rumor that police had beaten a black cabdriver to death triggered five days of looting and rioting in Newark, N.J. Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, whose father and poet Amiri Baraka was an important critical voice in that moment, talks with Steve Inskeep.' -- Morning Edition

Amiri Baraka | Neal Boenzi/The New York Times 'On July 12, 1967, a rumor that police had beaten a black cabdriver to death triggered five days of looting and rioting in Newark, N.J. Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, whose father and poet Amiri Baraka was an important critical voice in that moment, talks with Steve Inskeep.' -- Morning Edition

Published on July 13, 2017 08:03

July 12, 2017

Octavia Butler: Writing Herself Into The Story

'An exhibit at the Huntington Library shows visitors how famed science fiction writer Octavia Butler created a career for herself in a genre that had few women and even fewer African-Americans -- with Karen Grigsby Bates' -- Code Switch

'An exhibit at the Huntington Library shows visitors how famed science fiction writer Octavia Butler created a career for herself in a genre that had few women and even fewer African-Americans -- with Karen Grigsby Bates' -- Code Switch

Published on July 12, 2017 18:20

July 11, 2017

White & Woke? Chevara Orrin on the Role of Whites Dismantling the System of White Supremacy They Created

'The SNCC Digital Gateway invited young activists to address questions that SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) grappled with back in in the 1960s.Activist Chevara Orrin discusses the role of Whites in dismantling White Supremacy.' -- SNCC Digital Gateway

'The SNCC Digital Gateway invited young activists to address questions that SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) grappled with back in in the 1960s.Activist Chevara Orrin discusses the role of Whites in dismantling White Supremacy.' -- SNCC Digital GatewayCreated and Dismantled By White People - Chevara Orrin from SNCC Digital Gateway on Vimeo.

Published on July 11, 2017 16:44

July 10, 2017

Food Grails: How New Orleans Birthed a Vietnamese Po 'Boy Movement

'For this episode of Food Grails, we head to New Orleans. Forty years ago, Vietnamese migration to NOLA introduced bánh mì to po' boy country. Now, the lines between two iconic sandwiches are blurring. To find out what happens when you mash up the Mississippi Delta and the Mekong Delta, we spoke to New Orleans legend Curren$y, Times-Picayune writer Brett Anderson, and Banh Mi Boys chef Peter Nguyen.' -- First We Feast

'For this episode of Food Grails, we head to New Orleans. Forty years ago, Vietnamese migration to NOLA introduced bánh mì to po' boy country. Now, the lines between two iconic sandwiches are blurring. To find out what happens when you mash up the Mississippi Delta and the Mekong Delta, we spoke to New Orleans legend Curren$y, Times-Picayune writer Brett Anderson, and Banh Mi Boys chef Peter Nguyen.' -- First We Feast

Published on July 10, 2017 06:45

Inside the Work and Mind of Nick Cave

Steven G. Smith for The Boston Globe'Nick Cave, one of contemporary art's most towering figures guides through his astonishing new exhibition at MASS MoCA.' -- New York Public Library

Steven G. Smith for The Boston Globe'Nick Cave, one of contemporary art's most towering figures guides through his astonishing new exhibition at MASS MoCA.' -- New York Public Library

Published on July 10, 2017 06:29

July 8, 2017

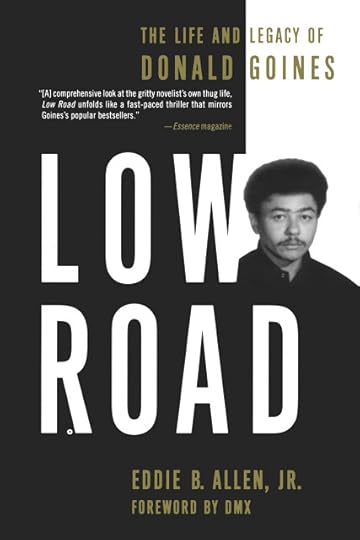

A Hustler’s Legacy: Donald Goines

A Hustler’s Legacy: Donald Goinesby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

A Hustler’s Legacy: Donald Goinesby Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Donald Goines has been name dropped by just about everyone in hip-hop—Nas’s “Black Girl Lost”, for example, is based on Goines’s 1973 novel of the same name. DMX portrayed the character King David in a film adaptation of Goines’s Never Die Alone. In many ways, the very genre of so-called Gangsta ap would have never existed if Goines had never put pen to paper, but who really was this former hustler-turned-literary folk hero? In his book, Low Road: The Life and Legacy of Donald Goines, journalist Eddie B. Allen, Jr. illuminates the life and writings of arguably the most influential chronicler of Black urban life in the post-World War II era.

Allen was first introduced to the work of Donald Goines as a kid—an older female cousin was reading a copy of his first published novel Dopefiend: Story of a Black Junkie (1971). Years later as he pursued a career as a journalist he could appreciate the ghetto realism of Goines’s writing. “But I had not learned exactly how real the details of the novel were” Allen reflects, “they had been taken directly from experiences and observations in the life of Donald Goines.” This was something that became clearer to Allen as he tried to pull together slithers of information about a man whose books, according to his publishers, have sold more than 5 million copies, but whose family couldn’t remember where he was buried.

What we know about Goines is that he, like so many, was profoundly inspired by the work of Robert Beck—Iceberg Slim for the uninitiated—whose autobiography Pimp: the Story of My Life (1967) caught Goines attention when he was in prison. It was with Pimp in mind that Goines began to pen his first pieces of urban fiction—the precursor to today’s so-called “street” literature.

The mass appeal that Pimp found among black audiences in the 1960s was not surprising. Iceberg Slim represented an undistilled take on Black urban life, a view that was not mediated by front-page Negrotarians or White tastemakers. As Allen describes it, “Pimp was a form of literary insubordination…it directly challenged notions, stereotypical and otherwise, about the American image of black men and sexuality.” (106)

What we also know about Goines is that he had the epitome of the hustler’s work ethic—he wrote 16 books in a four year period from his release from prison in 1970 and his murder in 1974. Years before “can’t knock the hustle” and “on my grind” became Hip-hop mantras, Goines embodied the “hustle” in ways that foreshadowed notions of work within the culture industries during the era of hip-hop.

But Goines, as Allen asserts, was also the “product of the post-Depression era city, where men of color still walked a fine line between pride and self-preservation.” (vii) In other words, it might have been all about the “hustle”, but with an attention to craft and detail, that ultimately separates the work of Goines and Beck from your favorite mumble rapper.

All of Goines’s novels have been published by Holloway House, a LA-based outfit that bills itself as the “World’s Largest Publisher of Black Experience Paperbacks.” Holloway was the same house that made serious money off the publication of Beck’s Pimp, as well as Louis Lomax’s To Kill a Black Man (1968) and Robert H. deCoy’s classic The Nigger Bible (1967). The irony, of course, is that Holloway House was a white owned publishing company.

That Holloway House continues to make money off of Goines’s work, including film rights for Crime Partners (2003) and Never Die Alone (2004),underscores Allen’s suggestion that figures like Goines and Beck were being pimped—“put out on the street to make money for a White owned publishing company.” Indeed, whatever money Goines made off of writing, largely supported his heroin addiction.

According to Allen, when Goines and his wife Shirley were murdered in October of 1974, many regarded him as “just another dead junkie.” Invisible to a White owned culture industry that made money off of him and ignored by a Black gate-keeping elite that despised the characters he brought to life in his novels, Donald Goines death barely registered, even amongst hard core fans of his work. Fittingly and thankfully, Eddie B. Allen, Jr.’s Low Road: The Life and Legacy of Donald Goines brought that legacy into even sharper focus.

Published on July 08, 2017 17:11

Theaster Gates in Conversation with Lisa Lee and Romi Crawford

'

Open Engagement

featured a conversation about the role of artists and the power of objects in memory, trauma, history, place, and healing between ReBuild Founder + Executive Director Theaster Gates and Open Engagement 2017 Curators Lisa Lee & Romi Crawford.' -- Open Engagement

'

Open Engagement

featured a conversation about the role of artists and the power of objects in memory, trauma, history, place, and healing between ReBuild Founder + Executive Director Theaster Gates and Open Engagement 2017 Curators Lisa Lee & Romi Crawford.' -- Open Engagement

Published on July 08, 2017 14:10

Serpentine Cinema: Lucy Raven in Conversation with Arthur Jafa

'Artist Lucy Raven in conversation with artist, filmmaker and cinematographer Arthur Jafa. On 9 February 2017, artist, filmmaker and cinematographer Arthur Jafa presented two films; APEX (2013) and Mechanics of Empathy (in progress) followed by a conversation with Lucy Raven. Jafa’s multidisciplinary practice uses film to investigate and question issues surrounding Black cultural politics and Black visual aesthetics modeled on the centrality of Black music to America’s cultural history.' -- Serpentine Galleries

'Artist Lucy Raven in conversation with artist, filmmaker and cinematographer Arthur Jafa. On 9 February 2017, artist, filmmaker and cinematographer Arthur Jafa presented two films; APEX (2013) and Mechanics of Empathy (in progress) followed by a conversation with Lucy Raven. Jafa’s multidisciplinary practice uses film to investigate and question issues surrounding Black cultural politics and Black visual aesthetics modeled on the centrality of Black music to America’s cultural history.' -- Serpentine Galleries

Published on July 08, 2017 14:02

Greg Tate on Kerry James Marshall + the Black Tradition of Image Making

'Greg Tate has been a leading voice on contemporary Black music, art, literature, film, and politics since launching his career at the Village Voice in the early 1980s. Through his signature mix of vernacular poetics and cultural criticism, Tate elucidates how race, gender, and class shape popular culture and why visionary Black aesthetics, philosophies, and politics help define 21st-century America. He is also a musician, leading the conducted improvisation ensemble Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber. Tate lectures on the work of Kerry James Marshall.' -- MOCA

'Greg Tate has been a leading voice on contemporary Black music, art, literature, film, and politics since launching his career at the Village Voice in the early 1980s. Through his signature mix of vernacular poetics and cultural criticism, Tate elucidates how race, gender, and class shape popular culture and why visionary Black aesthetics, philosophies, and politics help define 21st-century America. He is also a musician, leading the conducted improvisation ensemble Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber. Tate lectures on the work of Kerry James Marshall.' -- MOCA

Published on July 08, 2017 13:53

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.