Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 494

October 1, 2017

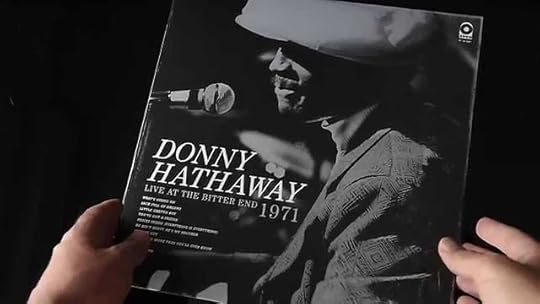

“And I’m Writing This Review for You”: A Review of Emily J. Lordi’s Donny Hathaway Live

“And I’m Writing This Review for You”: A Review of Emily J. Lordi’s Donny Hathaway Liveby I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“And I’m Writing This Review for You”: A Review of Emily J. Lordi’s Donny Hathaway Liveby I. Augustus Durham | @imeanswhatisays | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Charting the importance of Donny Hathaway to comprehend a soul (and post-soul) aesthetic is perhaps an inestimable endeavor. When coupling this with the fact that almost 38 years after his death, there had been no singular nonfiction monograph that outlined his life and songbook, one acknowledges that such silence likely signifies that there were precisely no words. That is until Emily J. Lordi chronicles the politics of his performativity in Donny Hathaway Live (Bloomsbury Academic, 2016; 144 pages).

This text—itself miniaturized, hence its inclusion in the 33⅓ series—calculates a kind of mathematics that the previous paragraph already begins to deduce: can an author capture in a bound spine, even fractionally, the sum of an artistic life that concludes with what may have been an accidental, or purposive, flight (97-112)? Is there a pivotal difference between the individual and the collective? How does a genius cultivate an atmospheric product while simultaneously plunging the interiority of his “black melancholy” à la Treva Lindsey (39)? And what is the love quotient that so pervades the ear that listeners feel compelled to conjure a pianistic paragon from a self-professed pear (26)? The fruitfulness of this book is that one never hungers.

There is an odd form of anxiety in attempting to explain what the book accomplishes because training, both as a musician and scholar, suggests that formalism is the proper foundation for discursive gymnastics. I venture to surmise that Lordi wrestles with this dis-ease as well when she states in a rather parabolic manner, “The conventional way to tell Hathaway’s story is not to dwell on this somber truth [the “painful irony . . . that the stunning vitality” the Live album “captures would be so short-lived”] but to move past it and end on a positive note . . . But I want to linger in the matter of endings. Doing so is instructive with Hathaway, because he was a master of them” (5).

Allow me to make a tumbling pass: Musiq Soulchild has a lyric where he vocalizes: “But now that you’re gone/The story begins/It’s the ending of the end/Of an endless end/”. As one of Donny’s artistic beneficiaries, interpolating giving up in the cause of you and me, he further ponders in the chorus that if you can’t have the one you love, then whereareyougoing in your life? By internalizing this musiqal provocation, I arrive, which is to say dismount, at the notion that by beginning with endings, Lordi provides us with directions for encountering comfort in the fulfillment of the unresolved (119).

As much a prodigy as a prophet, Hathaway telling his grandmother at the ripe age of four that he could hear the most beautiful music in his head (16) stunningly foreshadows Stevie Wonder’s 1972 project Music of My Mind. That Wonder’s subsequent album, Talking Book (1972), is indebted to Hathaway (112)—in part because he does a live cover at UCLA of “Superwoman (Where Were You When I Needed You)”, one of two singles from the mind music album (89)—testifies to how Donny changed the game through sheer homage, wading in the great black pool of genius. At the same time, such an (in)formal education further cultivates itself at Howard University and after, more specifically in tandem with his comrade Roberta Flack (23; 40-7). What kind of unresolved fulfillment do we witness when music majors steal away to get their groove back under the “watchful eye” of administrators? (23)

The music department as a crossroads for preparing the world for soundscapes that soundtracked our lives is nothing short of serendipity; we resound en masse: Thank You Master (For Their Soul) (There). Donny understood the complexity of formalism even as it took on a utility for his own productivity. When he imparts to Victor Rice that American music is BLACK and that European masters lack the SOUL that only black musicians can give (31), his stance suggests that insofar as everything is everything, one could simply replace such a ubiquitous category with the word BLACK, on either side of the verb, and never miss a beat. Being able to recount these moments of black genius not only solidifies Hathaway as an archival artist, but also conceives Lordi as an archivist in her own right.

She is immensely meticulous at engendering compassion while filling the rests and stops of the cantata that is Hathaway’s life. The reader gains an exemplar for how to be a fan critically. Likewise, she outlines the stakes of Hathaway’s ethics and how they still hold sway today. This is made clear when she deploys the idea of “getting together” (3), a politics of assemblage or Fred Moten’s construction of the ensemble. What Lordi does, whether one perceives it as subtle or overt, is lay bare the necessary ease of citation. In her estimation, Donny always understood he was in conversation, in partnership, with others, and not the passive receptor of brilliance to then actively engage in improper naming (or none at all). She deftly conveys this affect when speaking about Hathaway’s mental health.

The communal enactment of I-we as a mode of honorific is commonplace. Lordi’s search for the first-person singular concretizes the reality the some willingly give up their subjectivity as a metonymic gesture; the transformation from the one to a part of the whole is an object formation which proves that people who choose such a social position can and do resist. This is what Lordi means when she concedes, “Hathaway’s greatest success came through his recreation of other artists’ music [such that it] might reflect this broader history of interdependence . . . submerging the ‘I’ and the ‘we” that was always his implicit theme” (103). Donny’s work ethic surfaces when he makes the calculation that though “he wanted credit and compensation for his work,” he also wanted “to ensure that other artists received theirs” (110). Lordi’s constant signposting of him promoting the genius of his fellow musicians throughout the text (60; 70-1; 111), often at the cost of his own livelihood, situates the blackness of his music and his politics.

Getting together, as in self-actualizing, is a precursor to gathering oneself in order to be a participant in a get-together. Blackness in the pocket. In a real sense, then, the Night that happens during the recording session when Hathaway charges white people with stealing his music and sound (109) contrives him as kindred with Moishe the Beadle. And as Lordi further opines: what one diagnoses as “sickness” culturally predates the ill and, in this contemporary moment, has yet to be quarantined (110). But wherearewegoing in our life together?

If Lalah Hathaway teaches us anything as the text draws to a close, it might be to locate ourselves at the park for enacting the extraordinary (115). Lordi may be steering us toward something like the experience of a live show to give life to the performer and get our lives from him/her simultaneously. But if we can’t have Donny, the one we love, in the flesh, I believe he offers us two options: a world that gives us permission to get ourselves in gear, keep our stride, in order to sing his greatest songs and keep going, going on; or to meet him in a dream.

That may be all we have for all we know.

+++

I. Augustus Durham (ABD) is a fifth-year doctoral candidate in English at Duke University. His work focuses on blackness, melancholy and genius.

Other essays from I. Augustus Durham:

How “Black” Is Your Science Fiction?KING Me: Soul for a Black FutureMr. White! *said in echo*: Charting the Black(ness)

Published on October 01, 2017 09:45

September 30, 2017

Art, Passion, and Pain for The Puerto Rican Diaspora

'What does it mean to be Puerto Rican in 2017? The island territory, in the midst of financial ruin, is now grappling with the devastation brought from a Category 4 hurricane. Esmeralda Santiago left Puerto Rico for New York in 1961, when she was only 13 years old. Since then, the island stayed with her — through language, culture, and work. Santiago is the author of the books "When I Was Puerto Rican" and "Conquistadora." She joins The Takeaway to talk about how she’s been processing the recent events in Puerto Rico as a member of the island's diaspora.' -- The Takeaway

'What does it mean to be Puerto Rican in 2017? The island territory, in the midst of financial ruin, is now grappling with the devastation brought from a Category 4 hurricane. Esmeralda Santiago left Puerto Rico for New York in 1961, when she was only 13 years old. Since then, the island stayed with her — through language, culture, and work. Santiago is the author of the books "When I Was Puerto Rican" and "Conquistadora." She joins The Takeaway to talk about how she’s been processing the recent events in Puerto Rico as a member of the island's diaspora.' -- The Takeaway

Published on September 30, 2017 18:05

Bilal on Not Staring Into Erykah Badu's Eyes: "It's Like Staring Into the Universe"

'In this clip, Bilal recounts the creative genius of Dr. Dre and his meticulous approach to developing a song. Bilal also talked about his time as part of the creative collective, The Soulquarians, which included Common, Mos Def, Questlove, Erykah Badu, Q-Tip, Talib Kweli, James Poyser, D'Angelo, and J Dilla. He spoke further about working with J Dilla and how impactful his music is long after his passing. Bilal naturally had to speak about Erykah Badu who he says has eyes that look like you're staring in the universe. He called Badu enchanting and that she possesses an energy that helps bring out a person's true self.' --

djvlad

'In this clip, Bilal recounts the creative genius of Dr. Dre and his meticulous approach to developing a song. Bilal also talked about his time as part of the creative collective, The Soulquarians, which included Common, Mos Def, Questlove, Erykah Badu, Q-Tip, Talib Kweli, James Poyser, D'Angelo, and J Dilla. He spoke further about working with J Dilla and how impactful his music is long after his passing. Bilal naturally had to speak about Erykah Badu who he says has eyes that look like you're staring in the universe. He called Badu enchanting and that she possesses an energy that helps bring out a person's true self.' --

djvlad

Published on September 30, 2017 17:54

Bullet Holes and Rosé: Whitewashing Brooklyn

'The Brooklyn bar Summerhill caused an uproar this summer when the owner advertised its "bullet hole-ridden walls" in a press release—and the holes are still there. We caught up with the local Crown Heights community to chat about gentrification, and its impact on longtime neighborhood residents.' -- The Root

'The Brooklyn bar Summerhill caused an uproar this summer when the owner advertised its "bullet hole-ridden walls" in a press release—and the holes are still there. We caught up with the local Crown Heights community to chat about gentrification, and its impact on longtime neighborhood residents.' -- The Root

Published on September 30, 2017 17:44

On Black Creativity: A Conversation with Toshi Reagon + Daniel Bernard Roumain + Kamilah Forbes

'Composers Toshi Reagon and Daniel Bernard Roumain, Apollo Theater executive producer Kamilah Forbes and vocalist and Helga podcast host Helga Davis in conversation about the contributions of black artists to contemporary opera and the narratives they are driving in American culture. The evening includes performances from new works, including Reagon's "Octavia E. Butler's Parable of the Sower," an operatic adaption of the science fiction novel, and Roumain's "We Shall Not Be Moved," an interdisciplinary opera co-commissioned and co-produced by Harlem's Apollo Theater, Opera Philadelphia and London's Hackney Empire, which will have its New York premiere on Friday, October 6 at The Apollo.'

'Composers Toshi Reagon and Daniel Bernard Roumain, Apollo Theater executive producer Kamilah Forbes and vocalist and Helga podcast host Helga Davis in conversation about the contributions of black artists to contemporary opera and the narratives they are driving in American culture. The evening includes performances from new works, including Reagon's "Octavia E. Butler's Parable of the Sower," an operatic adaption of the science fiction novel, and Roumain's "We Shall Not Be Moved," an interdisciplinary opera co-commissioned and co-produced by Harlem's Apollo Theater, Opera Philadelphia and London's Hackney Empire, which will have its New York premiere on Friday, October 6 at The Apollo.'

Published on September 30, 2017 07:50

‘I’m Interested in Poetry’ -- TateShots Conversation with Visual Artist Isaac Julien

'Isaac Julien, CBE, is an award winning filmmaker and installation artist. He rose to prominence with the 1989 film Looking for Langston, a poetic documentary and homage to Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. His work has since explored a variety of issues including black identity, diaspora, migration and capital. Julien was born in 1960 in London, where he currently lives and works. In this film we visit the artist in his studio to explore three key works across his career.' -- Tate

'Isaac Julien, CBE, is an award winning filmmaker and installation artist. He rose to prominence with the 1989 film Looking for Langston, a poetic documentary and homage to Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. His work has since explored a variety of issues including black identity, diaspora, migration and capital. Julien was born in 1960 in London, where he currently lives and works. In this film we visit the artist in his studio to explore three key works across his career.' -- Tate

Published on September 30, 2017 07:31

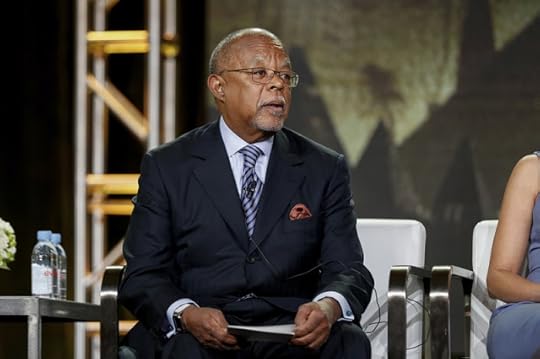

Henry Louis Gates Jr. on Season 4 of 'Finding Your Roots'

'Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., author and Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, joins us to discuss season 4 of his PBS series Finding Your Roots. In each episode, Gates dives into the ancestry of a celebrity to learn about their family's origins, connections to famous/infamous people and surprising secrets are part of their family's past. Season 4 guests include Amy Schumer, Larry David, Bernie Sanders, Questlove, Lupita Nyong’o, Christopher Walken and Aziz Ansari. ' -- The Leonard Lopate Show

'Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., author and Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, joins us to discuss season 4 of his PBS series Finding Your Roots. In each episode, Gates dives into the ancestry of a celebrity to learn about their family's origins, connections to famous/infamous people and surprising secrets are part of their family's past. Season 4 guests include Amy Schumer, Larry David, Bernie Sanders, Questlove, Lupita Nyong’o, Christopher Walken and Aziz Ansari. ' -- The Leonard Lopate Show

Published on September 30, 2017 06:23

First Person: Playwright Donja Love on Boundless Black Masculinity

'In the season 2 premiere of PBS Digital Studios’

First Person

, host Tonilyn Sideco talks with playwright Donja Love about his experience of surviving depression and suicide ideation, expanding notions of Black masculinity, and what he refers to as the radical power of “softness”.' -- First Person

'In the season 2 premiere of PBS Digital Studios’

First Person

, host Tonilyn Sideco talks with playwright Donja Love about his experience of surviving depression and suicide ideation, expanding notions of Black masculinity, and what he refers to as the radical power of “softness”.' -- First Person

Published on September 30, 2017 05:47

September 29, 2017

Left of Black S8:E3: Artist Pierce Freelon on His Vision for the City of Durham

Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal, chair of Duke's Department of African and African American Studies, speaks with Durham, N.C. mayoral candidate Pierce Freelon about town/gown relations, the city's rapid development, and his vision for Durham's marginalized communities.

Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal, chair of Duke's Department of African and African American Studies, speaks with Durham, N.C. mayoral candidate Pierce Freelon about town/gown relations, the city's rapid development, and his vision for Durham's marginalized communities.Freelon is the founder of Blackspace, a digital maker space in Durham where young people learn about music, film and coding, and he is frontman of the local jazz hip-hop band The Beast. He also co-founded Beat Making Lab, an Emmy-Award winning PBS web-series and social entrepreneurship community program.

Left of Black is hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced by Catherine Angst of the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University and in collaboration with the Center for Arts + Digital Culture + Entrepreneurship (CADCE) and the Duke Council on Race + Ethnicity (DCORE).

*** Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlack

Published on September 29, 2017 14:30

September 24, 2017

Black Star: 'Breathe' -- Director David Alexander Shares Vision of New Diverse Age in Cinema

'Nowness's new series Black Star was inspired by the British Film Institute’s recent season of the same title, celebrating the work of Black actors. For the first episode, director David Alexander, recipient of the Nelson Mandela Foundation Artist Award, introduces the voices of emerging actors Arnold Oceng and Leah Harvey. Here, Alexander talks about the significant setting for the film: "We visited the world-leading Pinewood Studios in Iver, outside of London, scouting for locations. When we got there we realised we were the only black filmmakers around."' --

Nowness

'Nowness's new series Black Star was inspired by the British Film Institute’s recent season of the same title, celebrating the work of Black actors. For the first episode, director David Alexander, recipient of the Nelson Mandela Foundation Artist Award, introduces the voices of emerging actors Arnold Oceng and Leah Harvey. Here, Alexander talks about the significant setting for the film: "We visited the world-leading Pinewood Studios in Iver, outside of London, scouting for locations. When we got there we realised we were the only black filmmakers around."' --

Nowness

Published on September 24, 2017 18:35

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.