Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 486

November 22, 2017

#BackChannel: Responding To Sexual Assault, 'Mudbound' And #FreeMeek

The number of women coming forward with accounts of sexual assault and harassment continues to grow. The recent surge in allegations has put toxic masculinity and patriarchy in the spotlight, but many questions remain, such as: are Black and White accusers are treated differently.

The number of women coming forward with accounts of sexual assault and harassment continues to grow. The recent surge in allegations has put toxic masculinity and patriarchy in the spotlight, but many questions remain, such as: are Black and White accusers are treated differently.On this edition of WUNC ’s #BackChannel with Natalie Bullock Brown and Mark Anthony Neal, State of Things host Frank Stasio talks with them about sexual assault, the new Dee Rees’s directed film Mudbound and the recent strict sentencing of rapper Meek Mill for violating his probation (for a youthful offense) -- a sentencing that has generated protests in response to what is perceived as discrimination in the criminal justice system.

Natalie Bullock Brown, professor of film and broadcast media at St. Augustine’s University in Raleigh, and Mark Anthony Neal, chair of the department of African and African American Studies at Duke University in Durham.

Published on November 22, 2017 19:34

November 20, 2017

Hip hop met Rio de Janeiro and never stepped back

'America’s 1990s hip hop scene is reincarnated every Saturday night in what may seem like an unlikely location — beneath a highway overpass in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.' -- PRI's The World

'America’s 1990s hip hop scene is reincarnated every Saturday night in what may seem like an unlikely location — beneath a highway overpass in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.' -- PRI's The World

Published on November 20, 2017 19:43

bell hooks on the Roots of Male Violence Against Women

'In the wake of the Weinstein scandal, an ever-widening stream of accusations against powerful men has prompted a considerable amount of soul-searching. On Twitter and elsewhere, one book that has been mentioned is bell hooks’s The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, from 2004. The book was somewhat controversial among feminists because, rather than excoriating the worst behavior of men, hooks analyzes masculinity as a kind of regime that oppresses everybody, including men. She sees child abuse, sexual abuse, and shaming as rampant conditions that predispose psychologically damaged boys to violence. hooks tells David Remnick that if we don’t try to understand the male psyche we cannot solve the problem.' -- The New Yorker Radio Hour

'In the wake of the Weinstein scandal, an ever-widening stream of accusations against powerful men has prompted a considerable amount of soul-searching. On Twitter and elsewhere, one book that has been mentioned is bell hooks’s The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, from 2004. The book was somewhat controversial among feminists because, rather than excoriating the worst behavior of men, hooks analyzes masculinity as a kind of regime that oppresses everybody, including men. She sees child abuse, sexual abuse, and shaming as rampant conditions that predispose psychologically damaged boys to violence. hooks tells David Remnick that if we don’t try to understand the male psyche we cannot solve the problem.' -- The New Yorker Radio Hour

Published on November 20, 2017 19:35

Fault Lines -- Confidential: Surveilling Black Lives Matter

'There is a long history of government surveillance of black civil rights groups in the US. It was supposed to have ended in the 1970s, but today there is a similar threat to Black Lives Matter (BLM), a movement fighting to end systemic violence against black people. Fault Lines investigates the scope and impact of police and FBI surveillance of black activists in the US.' -- Al Jazeera English

Published on November 20, 2017 19:25

First Person: Surviving Racism & Cancer as a Queer Woman

'In season 2 episode 4 of PBS Digital Studios’

First Person

, host Aaryn Lang talks with Sex Educator and Activist Ericka Hart about her experience as a black Cancer survivor undergoing treatment in a world where she didn't see herself and what motivates her activism as a queer black woman.' -- First Person

'In season 2 episode 4 of PBS Digital Studios’

First Person

, host Aaryn Lang talks with Sex Educator and Activist Ericka Hart about her experience as a black Cancer survivor undergoing treatment in a world where she didn't see herself and what motivates her activism as a queer black woman.' -- First Person

Published on November 20, 2017 18:25

Puedo Hacerte Una Foto: A Portrait of Cuba

'“Cuba hits you,” explain Rosanna Webster and Phoebe Henry, the directorial duo behind this new film: “it is a complete sensory overload.” This new visual essay accelerates down wild roads, careening through the streets of Havana, matching Webster and Henry’s aesthetic intuition—born from their work in fashion—with its own break-neck pace. With echoes of 1964's sensorial and deeply photogenic I am Cuba, A Portrait of Cuba conjures its own visceral hymn to a nation stepping through the 21st century. Unlike the monochrome of the earlier work, Webster and Henry’s cinematic poem bursts with richness and uncontrollable color.' --

Nowness

'“Cuba hits you,” explain Rosanna Webster and Phoebe Henry, the directorial duo behind this new film: “it is a complete sensory overload.” This new visual essay accelerates down wild roads, careening through the streets of Havana, matching Webster and Henry’s aesthetic intuition—born from their work in fashion—with its own break-neck pace. With echoes of 1964's sensorial and deeply photogenic I am Cuba, A Portrait of Cuba conjures its own visceral hymn to a nation stepping through the 21st century. Unlike the monochrome of the earlier work, Webster and Henry’s cinematic poem bursts with richness and uncontrollable color.' --

Nowness

Published on November 20, 2017 17:03

The Reformatory: An Interview with Tananarive Due

'In this podcast, the award-winning writer Tananarive Due reads her story, “The Reformatory,” featured in Boston Review's 2017 literary issue,

Global Dystopias

. She also talks to Avni Sejpal about history as a dystopia, Afrofuturism, and the wondrous possibilities of James Baldwin writing science fiction.' -- Boston Review

'In this podcast, the award-winning writer Tananarive Due reads her story, “The Reformatory,” featured in Boston Review's 2017 literary issue,

Global Dystopias

. She also talks to Avni Sejpal about history as a dystopia, Afrofuturism, and the wondrous possibilities of James Baldwin writing science fiction.' -- Boston Review

Published on November 20, 2017 04:14

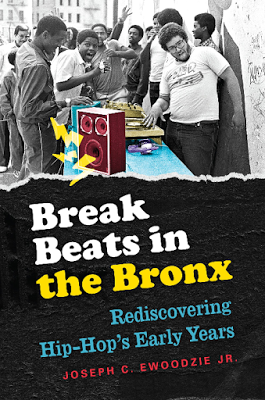

New Rhymes Over An Old Beat: A Review of Break Beats in the Bronx

New Rhymes Over An Old Beat: A Review of Break Beats in the Bronxby Tyler Bunzey | @tbunz3 | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

New Rhymes Over An Old Beat: A Review of Break Beats in the Bronxby Tyler Bunzey | @tbunz3 | NewBlackMan (in Exile)Hip-hop heads know how the story goes—a young man named Clive Campbell, also known as DJ Kool Herc, agreed to DJ his sister’s party at the community center on 1520 Sedgwick Ave. on August 11, 1973, and when he began to play only the break beats of funk records to get people moving, unto us Hip-Hop was born. After this first party, DJs Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa riffed on Herc’s initial spinning of break beats, Flash with his Quick Mix Theory and dual turntables and Bambaataa with his eclectic pastiche of samples. This Hip-Hop Holy Trinity created the culture that was led by DJs, supported by emcees and b-boys and b-girls, and promulgated by graffiti artists. Hip-hop culture existed in this pure form, getting its energy and momentum from city lampposts and disillusioned youth alike, until it was crucified by the commodification of Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979, and the unadulterated urban youth culture began the process of becoming morphing into a industrial, emcee-centered, worldwide, popular machine.

But Joseph C. Ewoodzie Jr. disagrees. His first book, Break Beats in the Bronx: Rediscovering Hip-Hop’s Early Years (University of North Carolina Press) seeks to reimagine this master narrative of early Hip-Hop history, a period in time that he sees as largely unexamined by scholarship on Hip-Hop. Ewoodzie does not seek to destabilize our understanding of the creation and formation of early Hip-Hop, but rather he looks to provide new and “fresh” evidence that can give us a clearer picture of how Hip-Hop really functioned in New York society in the 1970s (11). He (re)mixes interviews from the Museum of Popular Culture (MoPOP) and from independent Hip-Hop historian and Harlem native Troy L. Smith with academic sociological theory in order not only to examine Hip-Hop’s creation and development as an aesthetic culture but also to explain the role that Hip-Hop played in the communities in which it was created.

Ewoodzie artfully balances revision with respect for Hip-Hop’s founders and the status that they have achieved. He does not seek to show that Herc, Flash, and Bambaataa are undeserving of the status that they have in Hip-Hop folklore, but rather Ewoodzie desires to “move from a heroic account toward a people’s history of Hip-Hop” (5). Ewoodzie, a professor of Sociology at Davidson College, argues that Hip-Hop is not the product of some mystifying and obscure Black artistic genius, and instead it arose from “the lives—including the joys, pains, interests, inclinations, and dispositions—of a cohort of Black and Latino teens who came of age during the 1970s in the Bronx” (5).

He frames his work through the sociological theory of boundary making, treating the first practitioners of Hip-Hop—like Herc and Flash—as vanguards in the development of new cultural boundaries. He echoes other historical accounts of Hip-Hop and claims that early Hip-Hop was contextualized by the Bronx’s “poverty and chaos”—notably the construction of the invasive cross-Bronx expressway, the buildings set on fire almost daily by landlords trying to collect insurance money, and the devastating departure of factories during postwar deindustrialization (31).

Ewoodzie’s contribution to this received history is his explanation of how DJs specifically stepped into this sociological context and became lauded figures. He suggests that graffiti artists, although admired by many youth, were seen as “destructive” to the community both because of their anonymity and the nature of their practice (44). DJs, on the other hand, contributed to the community by keeping youth out of violent gangs while providing a relatively safe space, and they developed followings that the graffiti artists’ anonymity prevented them from gaining

Ewoodzie also addresses the reasons that Hip-Hop developed specifically in the Bronx and why other DJs, such as DJ Hollywood, did not have the same street following that Bronx DJs had. Ewoodzie suggests that there were “proto-boundaries” set up between both the styles and the spaces of the practices of DJing in different boroughs (73). Questions of access, dress codes, music styles, sexual politics, and dancing styles all prevented cultural crossover between Bronx and other DJs. Bronx DJs gave people a sense of symbolic belonging because of their neighborhood specific followings, whereas other DJs generally catered to an uptown audience that did not value space and place as identity markers to the same degree. In other words, Bronx DJs did not necessarily bring a superior quality of talent to the culture that made them the figureheads of early Hip-Hop. They were instead perfect for their context, and the community was ready for figures like them to create safe and productive cultural space. An illustration of this point comes in Ewoodzie’s reference to Herc’s deification as the founder of Hip-Hop, in which he suggests “He was perfect for the times, and the times were perfect for him” (50).

In conjunction to his framing of the proto-boundaries of early Hip-Hop, Ewoodzie progresses to the mid-1970s in which Hip-Hop is forming what he calls an “internal logic” (81). This internal logic is marked by the development of conventions, both intentionally and unintentionally, alongside influences from outside the culture. Ewoodzie charts new developments in the culture, and he interestingly deconstructs the widely accepted notion that Hip-Hop consisted of only four cultural actions—DJing, MCing, graffiti writing, and breaking. He introduces selling tapes (103), dressing fly (125), performing routines (125), and making flyers (134) as all coequal, if not more important, than MCing in the years of early Hip-Hop. To Ewoodzie, it is important to acknowledge that the boundaries of early Hip-Hop culture were porous, and economic, cultural, and aesthetic concerns shaped cultural practices As a result, these early practices were in constant flux, and the received master narrative of Hip-Hop history is not adequate to see how the culture truly formed in its early years.

Ewoodzie concludes his discussion with an account of the solidifying of early cultural practices of Hip-Hop in the context of Sugar Hill Gang’s 1979 hit “Rapper’s Delight.” He suggests that Hip-Hop’s cultural identity became Black and male because of its connection to cultural boundaries in the Bronx. Using firsthand accounts, Ewoodzie demonstrates that early Hip-Hop practices were “structured” to get the attention of women, and he claims, “Hip-Hop became a masculine space because it helped the male participants onstage to perform their masculinity, especially their heterosexual desires” (142).

Likewise, early Hip-Hop practices were structured to represent a distinctly Black cultural identity despite the cross-cultural influences, namely those of Puerto Ricans in the Bronx. Ewoodzie suggests that despite the presence of prominent Puerto Rican MCs, DJs, b-boys, and graffiti artists in the culture, “boundaries did persist between the two groups, and each guarded its sense of racial and ethnic distinctness” (162).

Ewoodzie ends his work by describing how the rise of MCs with the production of “Rapper’s Delight” permanently changed the culture. Pre-“Rapper’s Delight,” Hip-Hop was an insular culture, governed by those who practiced it. But with the rise of MC performances, parties began to mirror concerts instead of spontaneous selections of music curated by a central figure (177). “Rapper’s Delight” figured Hip-Hop as a concert-based practice, since it eliminated the DJ altogether and figured the emcee’s work as a performance to watch, not one to dance to. Control shifted from interior Hip-Hop practitioners to exterior commodity markets, and Hip-Hop was indeed indelibly transformed, as received history suggests.

Taken as a whole, Ewoodzie’s work functions as more than simply a revision of Hip-Hop’s received history, although that is a major purpose of the work. He challenges his readership to use his methodology of combining sociological theories of boundaries and cultural formation with first-hand accounts of cultural developments and apply it beyond Hip-Hop in order transform perspectives about cultural boundaries, urban “decay,” and the rise of new cultural entities (190-91). He rightly sees his work as widely applicable beyond Hip-Hop scholarship, and the encouragement for replication of his methodology in his conclusion help to see how his work could be extended beyond his discussion therein.

His work merges sociology with history, combining knowledge-creating methods with new and fresh accounts that challenge accepted historical narratives. Perhaps we can read Ewoodzie’s work itself as a part of Hip-Hop cultural production. After all, he patches together theory and new historical accounts, and remixing that pastiche with received history of Hip-Hop, he creates a work that is funky, fresh, and resonates in the echoes of the sounds of the Bronx. Can I get a witness?

***

Tyler Bunzey is a Teaching Fellow and Doctoral Student in Department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill. Follow him on Twitter: @tbunz3

Published on November 20, 2017 03:56

November 19, 2017

Diaspora Talk: Josef Sorett -- Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics

At the John L.Warfield Center for African American Studies at the University of Texas at Austins, Professor Josef Sorett, Associate Professor of Religion and African-American Studies at Columbia University and Director of the Center for African-American Religion, Sexual Politics and Social Justice discusses his new book

Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics

(Oxford University Press).

At the John L.Warfield Center for African American Studies at the University of Texas at Austins, Professor Josef Sorett, Associate Professor of Religion and African-American Studies at Columbia University and Director of the Center for African-American Religion, Sexual Politics and Social Justice discusses his new book

Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics

(Oxford University Press).

Published on November 19, 2017 18:48

Sound + Visuals: José James Interprets the Bill Withers Classic "Better Off Dead"

In advance of a new tour and album Lean On Me: José James Celebrates Bill Withers, José James is joined by is band — Sullivan Fortner on keyboards, Brad Allen Williams on guitar, Ben Williams on bass and Nate Smith on drums — in a video performance of Bill Withers's "Better Off Dead."

In advance of a new tour and album Lean On Me: José James Celebrates Bill Withers, José James is joined by is band — Sullivan Fortner on keyboards, Brad Allen Williams on guitar, Ben Williams on bass and Nate Smith on drums — in a video performance of Bill Withers's "Better Off Dead." Better Off Dead by José James on VEVO.

Director: Joseph DiGiovannaProducers: José James, Joseph DiGiovannaComposer: Bill WithersCopyright: (C) 2017 Blue Note Records

Published on November 19, 2017 18:39

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.