Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 365

September 15, 2019

Beyond Elmo: How Puppets Teach Preschoolers Self-Control

'Puppets are regularly used on TV to talk to kids about their emotions. Now, in North Carolina, there’s new research into whether using puppets to teach social and emotional skills in the classroom is effective. To date, 240 preschool teachers have been trained in a classroom management program and puppet curriculum called Dinosaur School. Duke researcher Katie Rosanbalm is evaluating the program. She says children interact with the puppets at “a level of enthusiasm that you don’t see when a teacher is just leading a class,” causing them to absorb the information at a deeper level.' -- Ways & Means

'Puppets are regularly used on TV to talk to kids about their emotions. Now, in North Carolina, there’s new research into whether using puppets to teach social and emotional skills in the classroom is effective. To date, 240 preschool teachers have been trained in a classroom management program and puppet curriculum called Dinosaur School. Duke researcher Katie Rosanbalm is evaluating the program. She says children interact with the puppets at “a level of enthusiasm that you don’t see when a teacher is just leading a class,” causing them to absorb the information at a deeper level.' -- Ways & Means

Published on September 15, 2019 04:24

Tshepo Madlingozi: There Is Neither Truth Nor Reconciliation in South Africa

"There Is Neither Truth Nor Reconciliation in South Africa": a conversation with Tshepo Madlingozi, Associate Professor and Director of the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. -- The Funambulist Podcast

"There Is Neither Truth Nor Reconciliation in South Africa": a conversation with Tshepo Madlingozi, Associate Professor and Director of the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. -- The Funambulist Podcast

Published on September 15, 2019 04:16

September 13, 2019

“I Am All of Them, They Are All of Me”: An Album Review of Rapsody’s EVE by Tyler Bunzey

“I Am All of Them, They Are All of Me”: An Album Review of Rapsody’s EVE

by Tyler Bunzey | @t_bunzey | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

“I Am All of Them, They Are All of Me”: An Album Review of Rapsody’s EVE

by Tyler Bunzey | @t_bunzey | NewBlackMan (in Exile) “Taped to the wall of my cell are 47 pictures: 47 Black faces: my father, mother, grandmothers (1 dead), grand- fathers (both dead), brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins (1st and 2nd), nieces, and nephews. They stare across the space at me sprawling on my bunk. I know their dark eyes, they know mine. I know their style, they know mine. I am all of them, they are all of me; they are farmers, I am a thief, I am me, they are thee.”—Etheridge Knight, “The Idea of Ancestry” (1986)

From the first words of this opening stanza by Etheridge Knight—Black Arts poet and incarceration survivor, the reader encounters a stark juxtaposition between the brutality of the speaker’s incarceration and the comfort of his ancestors. Before we know of his father, his mother, grandmothers, grandfathers, brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, cousins, nieces and nephews, we know that this ensemble encounters him from the wall of his presumably small, concrete cell. They “stare” not with him, initially, but “across the space” as he lies on his “bunk,” contemplating their presence. The encounter is initially alienating with the cold loneliness of the cell defining their interaction.

The next sentence, contrasting the coldness of his cell, immediately uncovers the intimacy that the presence of their 47 souls signifies to the speaker: “I know / their dark eyes, they know mine.” What greater intimacy in the space than knowledge of one another? In a system so intricately designed to disallow such intimacy within Black familial relationships, what incommensurable power is imbued within the speaker through this knowledge? The speaker pushes further, as it is more than knowledge but a shared presence, not just being with one another but being one another in a chorus of intimacy, belonging, and support that his ancestors give him: “I am all of them, they are all of me.”

In the opening lines of her magisterial third album EVE, Rapsody conjures this ancestral ensemble that provides comfort even in the darkest, most brutal times. After trading lines with Nina Simone in the prominent “Strange Fruit” sample echoing through the track, Rapsody opens EVE, “Emit light, Rap, or Emmitt Till.” This arresting line places Rapsody’s recurring theme of self-love, empowerment, and positivity in her body of work against the death that Black women like Nina Simone saw as ever-present in Black life. The subtle brilliance of this opening line comes from Till’s history: it is the pain and bravery of Till’s mother that enabled our national remembrance of him and galvanized a nation to begin to examine the practice of lynching in the US South. Wrapped in the aural arms of Simone whose music coupled protest (“Mississippi Goddamn”) with Black womanist life (“Four Women”), Rapsody captures the joy, pain, and resilience of Black womanhood in EVE.

With 16 tracks named after famous Black women—ranging from Nina Simone to Aaliyah, Myrlie Evers-Williams to Michelle Obama, Sojournor Truth to Afeni Shakur—Rapsody consciously invokes the historical strength of Black women. Although ready-made for a university class or reading guide for Black feminist criticism, EVE is more poessay than dissertation, using her signature rippity-rap style to represent the complexity of Black womanhood in the present through the legacies of those who have come before.

Beautifully interwoven with features from hip-hop royalty like Queen Latifah and the GZA, spoken word performances from poet Reyna Biddy, and soul-powered production from 9thWonder, Eric G., Mark Byrd, Khrysis, and Nottz, the album and its insistence for Black women to really live is certainly worthy of her demand for an “honorary Master’s.” EVE is the womanist answer to Pharoahe Monche’s injunction to “put them hands up / let’s live” (“Crazy,” JAMLA is the Squad II). True to hip-hop’s tradition, it merges the party with the political to excavate life in a society designed to extinguish it.

Rapsody’s invocation of her ancestors moves much deeper than simply in the titles to each track. In “Nina” Rapsody voices a call, “And still we persevere like all the 400 years of our own blood Africa / old panthers looking back like who going come up after us?” to which spoken word poet Reyna Biddy later fashions a response, “I'm extra-terrestrial, I was created different / I've been here many times before and I've never been defeated / And still, I will never be defeated.”

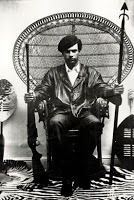

Rapsody, Biddy, and the artists of EVE are those who are answering the Panthers’ call, a group so integral to the album’s ethos that Rapsody references them throughout and even mimics Huey Newton’s iconic wicker chair photograph in the music video for “Oprah.” Like Biddy, Rap recognizes that those who have come before constitute her identity. Rapsody name drops in her bars over 128 times with proper name references making up a staggering 18.5% of the album’s lyrical content according to the Twitter account Hip-Hop by the Numbers.

This foregrounding of Black women’s legacies intertwines present figures with ancestral ones, weaving together a support system that lends Rapsody strength, identity, and courage to face a world that is invested in the erasure of women like her.

This foregrounding of Black women’s legacies intertwines present figures with ancestral ones, weaving together a support system that lends Rapsody strength, identity, and courage to face a world that is invested in the erasure of women like her. Like her Grammy-nominated album Laila’s Wisdom (2017), one of Rapsody’s primary themes of EVEis empowerment. She resurrects the tomboy fly aesthetic on “Aaliyah.” She shows that she’s “fine to the bone” on “Tyra.” She gives us a ladies night club anthem on “Michelle.” She declares Black women’s royalty on “Hatshepsut” with assistance in a stunning verse from Queen Latifah. Rapsody’s primary goal in EVE is to celebrate and empower such diversity of Black womanhood, but EVE is equal parts celebration and protest, suggesting that celebration and empowerment comes out of a need for Black women to articulate their own narrative:

“White men run this, they don't want this kind of passion (Talk) A Black woman story, they don't want this kind of rapping (Talk) They love a fantasy, they love the gun bang action (Talk) What good is a Black women to them? (Yeah) Raped us in slavery, they raping us again (Yes) Only put us on TV if our titties jiggling (Uh)”—Rapsody, “Cleo”

Without devolving into slut-shaming or promoting respectability politics, Rapsody tells us that her celebration of Black womanhood comes from political necessity. She recognizes that American culture has always reduced Black sexuality to the asexual Mammy or the hypersexualized Sapphire stereotypes, and part of EVE’s empowerment narrative comes from this need to diversify representation of Black womanhood and sexuality.

It’s precisely at this speaking back to American mainstream representations of Black womanhood that gives EVE its unique power, a power that Laila’s Wisdom doesn’t fully capture. Rapsody isn’t playing with us, and we can hear it. She shoots venom at RapRadar’s B.Dott Miller in “Cleo” after he tweeted that she wasn’t an elite emcee. After JID delivers this line “behind every great man is a bad bitch handling shit” on his guest verse on “Iman,” Rapsody hits him back with the final lines of the track, “I appreciate your elegance JID, but bro, love, tell me, who the fuck you calling a bitch?” This is a Rapsody that doesn’t take any shit, not even from her features. But it isn’t just fearless, don't-take-no-shit bars that make this album capture what Brittney Cooper might call eloquent rage.

It’s also Rapsody’s cadence, the play with her voice, the way she bends words, the beats themselves; every bit of this album’s content is a bit edgier and harder than what we heard in Rapsody’s past work. She wants to raise up the women around her and empower her community, but she isn’t going to cater to an audience unready for Black women to live. The push in her voice in almost every track registers the disrespect that she receives from other emcees and her discontent at feeling boxed in. Wielding liquid swords in her bars, she is cutting down the walls that industry folks place around female emcees and that American society places around Black women.

It’s too early to tell if EVE is a masterpiece, but if it isn’t, it’s damn near close. There are moments peppering the album that demonstrate lyrical intricacy, sonic mastery (shouts to the Soul Council!), playfulness, and a performance of ease. Laila’s Wisdom came out of an emcee trying to shift rap’s content into positivity and empowerment when the popular environment much preferred party-centric trap. EVE comes from an emcee who knows what the haters will say, shoots back at them like Cleo in Set It Off, and calls for solidarity among her sisters. There’s a self-possession on EVE complemented by a dense lyrical deftness that lends the album an unmistakable and magnetic aural power. Rapsody knows herself, she knows us, and she is beckoning us to grow together.

However, like in Knight’s invocation of ancestry as belonging, Rapsody’s call to empowerment is inextricable from the sexual and racial violence that Black women survive in America. Reyna Biddy tells us of this pain on “Nina” when she asks “Do you see my pain? Do I look like prey?” and reminds us of it as we leave “Afeni” with EVE’s parting words “My God don't like ugly, my God said she need an apology / Needs to know you see all the beauty she created / Needs you to know wouldn't be no you if it wasn't for us / My God said, "How much harder we got to love you?’”

This love comes from the ensemble. It comes from realizing the magnificent power of Black womanhood. It comes from the ancestors, the Ninas and Robertas, that made an emcee like Rapsody possible, and in EVEshe declares, “I am all of them, they are all of me.”

+++

Tyler Bunzey is a Teaching Fellow and Doctoral Student in Department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill. Follow him on Twitter: @tbunz3<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Helvetica; panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1342208091 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> -->

Published on September 13, 2019 18:35

September 12, 2019

The Secret Life of Credit Card Data

'Despite a federal privacy law covering our cards, a single swipe hands your data over to at least a half dozen different types of companies — retailers like Target, marketers, even hedge funds — all of whom are making big profits off that information. It’s all part of a sprawling and largely unregulated credit card-data economy. Geoffrey Fowler, a tech columnist with the Washington Post, joined The Takeaway to break down what is being shared and how it's being used. Fowler recently conducted an experiment where he used two different credit cards to buy two bananas at Target and then tracked where that information went.'

'Despite a federal privacy law covering our cards, a single swipe hands your data over to at least a half dozen different types of companies — retailers like Target, marketers, even hedge funds — all of whom are making big profits off that information. It’s all part of a sprawling and largely unregulated credit card-data economy. Geoffrey Fowler, a tech columnist with the Washington Post, joined The Takeaway to break down what is being shared and how it's being used. Fowler recently conducted an experiment where he used two different credit cards to buy two bananas at Target and then tracked where that information went.'

Published on September 12, 2019 03:35

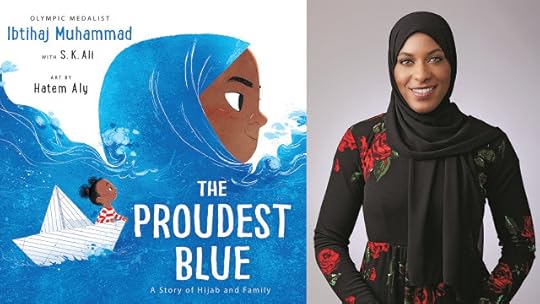

A New Book From Olympic Bronze Medalist Ibtihaj Muhammad

'Olympic fencer and Bronze Medalist, Ibtihaj Muhammad, joins All Of It to discuss her new children's book,

The Proudest Blue: A Story of Hijab and Family.'

'Olympic fencer and Bronze Medalist, Ibtihaj Muhammad, joins All Of It to discuss her new children's book,

The Proudest Blue: A Story of Hijab and Family.'

Published on September 12, 2019 03:25

September 10, 2019

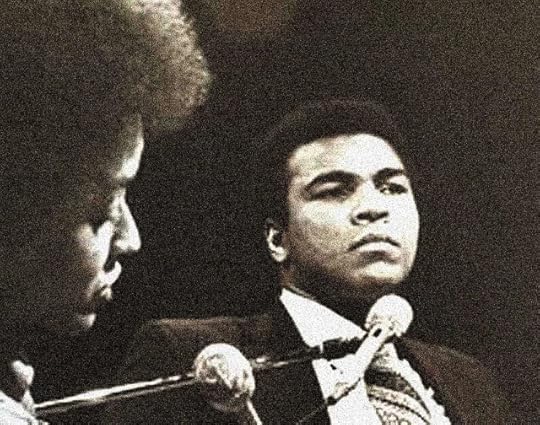

Nikki Giovanni and Muhammad Ali in Conversation (1972)

Two icons of an era of Black Radical Politics: Poet and activist Nikki Giovanni in conversation with Heavyweight boxing champion and the most prominent conscientious objector, Muhammad Ali.

Two icons of an era of Black Radical Politics: Poet and activist Nikki Giovanni in conversation with Heavyweight boxing champion and the most prominent conscientious objector, Muhammad Ali.

Published on September 10, 2019 07:29

September 9, 2019

How Ella Fitzgerald Is Influencing A New Generation Of Latinx Musicians

'Ella Fitzgerald's musical genius and influence is still being felt today. Latinx musicians Mabiland and Daymé Arocena explain how Fitzgerald inspires their music.' -- Weekend Edition Saturday

'Ella Fitzgerald's musical genius and influence is still being felt today. Latinx musicians Mabiland and Daymé Arocena explain how Fitzgerald inspires their music.' -- Weekend Edition Saturday

Published on September 09, 2019 19:44

Flying While Black: Stop the U.S. Congress from Raising Air Travel Taxes

Flying While Black: Stop the U.S. Congress from Raising Air Travel Taxesby Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr. | @DrBenChavis | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Flying While Black: Stop the U.S. Congress from Raising Air Travel Taxesby Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr. | @DrBenChavis | NewBlackMan (in Exile)NNPA NEWSWIRE - Working families in the African American community and beyond have a hard-enough time keeping up with daily expenses. Every mortgage payment, car payment, trip to the grocery store, stop at the gas station, or utility bill that shows up in the mail is a reminder of how expensive it is to afford basic needs. Now, lawmakers in the U.S. Congress have introduced legislation that threatens to add one more expense to that list.

On Capitol Hill, some lawmakers are championing what is essentially a regressive tax on airline passengers that would raise the cost of flying - painfully, on working families. If successful, the tax hike would burden African American travelers with significant additional fees on top of what is already required. Lawmakers who support the increase insist that the money will be spent on infrastructure improvement projects at airports. But, if our communities can no longer afford to fly, this becomes a moot point.

The tax, known as the passenger facility charge, is a locally enforced but federally authorized fee that every passenger must pay at U.S. commercial airports. Nearly every airport in America charges it. The fee is currently set at $4.50 per person per leg of a trip. Legislation has been introduced that would remove that cap, allowing airports to charge any amount they want.

Some have proposed raising the PFC to $8.50, nearly doubling the current tax. That would add a significant cost for all American families. Under that proposal, a family of four on a connecting flight would pay nearly $150 in this tax alone - a tax that is layered on top of the price of the ticket itself. Such a substantial increase could be the deciding factor between that family taking this vacation or staying home.

Fortunately, largely due to the recent surge of low-cost flights from many airlines, air travel has become a more obtainable luxury, remaining largely affordable for working people, whether in rural America, the suburbs or the inner cities. While still a relatively expensive proposition, air travel to get away on a vacation, or to visit far-away family and friends, without the proposed new tax, is still within reach for many individuals on tight family budgets. The near-doubling of the PFC tax will likely place air travel out of reach for many. And the reason for this hike is absurd.

The argument for the hike is that the additional money will pay for much-needed infrastructure improvement projects at airports nationwide. But here is the problem: America's airports don't need the extra money. Airport revenues are already growing strongly. Since the year 2000, airports have enjoyed revenue increases of 87 percent, without the cost of flights rising meaningfully. This growth drastically outpaces the actual cost of flying, even after factoring for inflation.

In addition, over the last decade, more than $165 billion in federal aid has been directed to airports for improvement projects at America's largest 30 airports alone. More than that, the so-called Aviation Trust Fund is expected to reach nearly $8 billion by the end of 2019.

And this summer alone, the Federal Aviation Administration has awarded hundreds of millions in renovation grants to airports across America earmarked for infrastructure improvements. It's also worth keeping in mind that air travel and tourism are now at or nearing all-time highs, meaning that airports are collecting more in PFC taxes than they know what to do with.

By contrast, the income of working Americans has been stagnant for years. Considering that airports are more profitable now than ever before, it is disappointing that they, with the backing of politicians in Washington, are now coming to average Americans and asking them to shoulder the cost.

America's airports are well-positioned to continue to fund infrastructure improvement projects without needlessly reaching into the pockets of America's working families and robbing them of one of the few affordable luxuries available to them. Congress must stand up for working people and refuse this tax increase.

Economic progress in America should empower African Americans and others. We in the Black Press of America will not be silent on this issue.

+++

Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr. is President and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) representing the Black Press of America. He can be reached at dr.bchavis@nnpa.org.

Published on September 09, 2019 19:33

September 8, 2019

Duke Law -- When They See Us: A Conversation with Raymond Santana and Yusef Salaam of the Exonerated Five

'Yusef Salaam and Raymond Santana, two members of the Exonerated Five, formerly known as the Central Park Five, tell their stories to a Duke Law audience. They are the subjects of the Netflix series "When They See Us," which focuses on the conviction and later exoneration of Mr. Salaam, Mr. Santana and three others in the infamous Central Park jogger case. Dean Kerry Abrams welcomes the panelists to Duke Law and Professor Brandon Garrett interviews Mr. Salaam and Mr. Santana about their experiences. A question and answer period follows. Sponsored by the Office of the Dean, the Center for Criminal Justice and Professional Responsibility, the Duke Law Innocence Project®, and the Criminal Law Society.' -- Duke University School of Law

Published on September 08, 2019 05:13

FRONTLINE -- Documenting Hate: Charlottesville

'FRONTLINE and ProPublica investigate the resurgence of white supremacists in America. An investigation into how the violent and infamous rally in Charlottesville became a watershed moment for the white supremacist movement. Correspondent A.C. Thompson shows how some of those behind the racist violence went unpunished and shines a light on the rise of new white supremacist groups in America. This film is part of an ongoing collaboration between ProPublica and FRONTLINE.' -- FRONTLINE PBS | Official

'FRONTLINE and ProPublica investigate the resurgence of white supremacists in America. An investigation into how the violent and infamous rally in Charlottesville became a watershed moment for the white supremacist movement. Correspondent A.C. Thompson shows how some of those behind the racist violence went unpunished and shines a light on the rise of new white supremacist groups in America. This film is part of an ongoing collaboration between ProPublica and FRONTLINE.' -- FRONTLINE PBS | Official

Published on September 08, 2019 04:55

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.