Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 262

December 19, 2020

Play the Tune: A Review of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe by Sasha Ann Panaram

Play the Tune: A Review of Steve McQueen’s Small Axe

by Sasha Ann Panaram | @SashaPanaram | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Music anchors acclaimed filmmaker Steve McQueen’s five-part anthology Small Axe (2020) in a particular time and place: the West Indian community in Britain in the 1960s, ‘70s, and 80s. From the steelpan drums that usher in the opening night of The Mangrove restaurant in 1968 in Notting Hill to the sweet tunes that comprise the reggae subgenre lovers rock, from the Jim Reeves melodies such as “The World is Not My Home” that bubble up in heated moments of confrontation between Black-British people and the police to reggae that dominates the latter films in the series, you cannot watch Small Axe without also listening to the history it records and retells. Through all this sound and fury, all this rhythm and rhyme, it is the subtle yet necessary first song that initiates the anthology – “Long, Long Time” by the Jamaican trio reggae group The Versatiles – that in many ways reveals exactly what we need to know about McQueen’s latest production: it’s been a long, long time coming. Indeed, as McQueen recently told TIME magazine, he started conceiving of this collection of films on the Black-British West Indian experience 11 years ago admitting he needed to cultivate the maturity necessary to address a subject so close to him.

Born in West London in 1969 to Philbert and Mary McQueen, the filmmaker is of Trinidadian and Grenadian descent. His parents belonged to the first generation of West Indians to settle in Britain between 1948 and 1970. Whereas McQueen’s previous films including Hunger and 12 Years a Slave address the plight of other nations like the 1981 Irish hunger strike and the life of a free African American man, Solomon Northup, caught and sold into bondage in 1841, Small Axe turns its attention to the director’s own familial and cultural history. In five standalone movies co-commissioned by BBC and Amazon, that premiered on November 15 in the United Kingdom, McQueen focuses on the lives of individual Black-British people and larger West Indian communities. According to him, “It is important for me that these films were broadcast on BBC, because it has accessibility to everyone in the country. These are national histories.” The anthology takes its name from a proverb made popular by the Jamaican reggae singer Bob Marley who once bellowed: “If you are the big tree, we are the small axe, ready to cut you down.”

Taken together, each of McQueen’s films capture the brutal interruptions that marked Black-British life in the mid-twentieth century: police-orchestrated raids, sexual harassment, and verbal abuse, for instance. However, where the films really succeed is in their documenting of the more subtle yet no less devastating ongoing attacks waged on Black-British people such as the demand for European cuisine in a West Indian restaurant (to which Frank Crichlow, the owner of The Mangrove indignantly replies, “We serve spicy food here!”), the mocking of accents, the endless surveillance, and the everyday dismissal, to name a few moments. As Doreen St. Félixkeenly observes, “McQueen wants to vanquish any idea that British racism is somehow more repressed and less violent than the American kind; he spotlights the myth of the country’s politesse in order to do some smashing of his own.”

Mangrove, the first film in the anthology, examines a landmark case in British history that lasted 55-days where nine Black Londoners were tried for incitement to riot at London’s Old Bailey following protests that accompanied the closing of Frank Crichlow’s (Shaun Parkes) The Mangrove, an all-night Trinidadian restaurant that served as a hub for British West Indian people. The jury eventually acquitted all of the defendants of the main charge and the trial resulted in the first acknowledgment of racial hatred in the Metropolitan police. As McQueen shows, several of the Mangrove Nine were British Black Panther members including Altheia Jones-LeCoint (Letitia Wright) and Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby), but Crichlow was not. Whereas Jones-LeCoint and Howe studied at the feet of C.L.R. James – a scene literally and lovingly depicted in the first installation when young people gather at the home of C.L.R. and Selma James – Crichlow was not drawn to politics in the same way and failed to realize the significance of The Mangrove in providing Black-British people a place to develop their Caribbean-British identities. However, as Howe stated in the trial, “Wherever a community is born it creates [the] community that it needs” and in this case, that community happened to revolve around Crichlow’s restaurant. Although the Mangrove Nine ultimately beat the charges, McQueen cautions against viewing the victory as a wholesale win. The final captioning of the film discloses that the Metropolitan police harassed Crichlow for 18 years following the trial and only in 1989 did they clear his name from the High Court.

Two other films, Red, White, and Blue and Alex Wheatle take their inspiration from true stories like Mangrove, but whereas Mangrovefocuses on a group of people, these films spotlight certain individuals. The third installment traces the life of Leroy Logan (John Boyega), a British-Jamaican who leaves his lucrative research job in forensics to join the Metropolitan Police. The film begins with Leroy, a young boy, waiting for his father Ken Logan (Steve Toussaint) to pick him up from school. In the interim, the police harass Leroy claiming he fits the description of a robber. When Ken arrives, he chastises the police. Then during the car ride home, he adamantly declares to Leroy, “I am the only authority you need” before warning his son to never give the police a reason to enter his yard. Later, when the police viciously and unnecessarily attack Ken, his son does not shun the Metropolitan police, but, on the contrary, he aspires to join them. On the day that Leroy meets fellow members of his police cohort he plainly states, “… I’m not here to make any friends. I’m here to bring change to this organization from the inside out.” This film seems “out of joint” (to borrow from Howe quoting William Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Mangrove) compared to the other films in the series. For one, none of the characters are fully realized as they are in Mangrove – each appear only as a faint shadow of who they could become. Further, the storyline seems out of sync when perceived alongside the conditions that surrounded McQueen’s release of Small Axe namely the ongoing pandemic of anti-black racism and calls to dismantle the police and for abolition.

Similarly, Alex Wheatle, the fourth installation in the series, features the life of the author who came from nothing when his mother abandoned him and his father gave him over to the British social-services bureaucracy. Set in Brixton, South London, which was partly made famous by the 1971 Clash song “The Guns of Brixton” whose lyrics read, “When they kick in your front door, how you gonna come, / With your hands on your head or on the trigger of your gun?”, the song’s violent overtones align with the violence in this film. In 1981, a set of Black-British people staged a series of demonstrations after the New Cross Fire – an inferno in a house party that killed 13 people. Wheatle was one of many protesters sent to jail. The film exposes a man trying to rebuild himself. In jail, he faces repeated confrontations with his Rasta cellmate Simeon (Robbie Gee). At one particular point of frustration, Simeon cries out, “Listen, man! What is your story?” to which Wheatle replies, “My story? I ain’t got not frickin’ story!” Therein lies the exchange that if embraced could have made for a more compelling film: entry into the life of Wheatle as a writer hailed now as the Brixton Bard and author of young adult literature. Stunned by his reply, Simeon, an avid reader committed to unlearning inherited Western modes of thought, hands over all of his books to Wheatle starting with James’s The Black Jacobins. We never see the writer Wheatle becomes, but we do see something else: a glimpse into how a book, a typewriter, a short story, or a pamphlet can inaugurate the beginning of a life – a life full of stories, a storied life – one never imagined.

Undoubtedly, McQueen’s most masterful film of the anthology is Lovers Rock. Mangrove, Red, White and Blue, and Alex Wheatle each address real life events and people, however, Lovers Rock, while it follows a fictionalized couple Martha (Amarah-Jae St. Aubyn) and Franklyn (Michael Ward) at a blues dance, still feels the most real out of the collection. There is an undeniable authenticity to the Small Axe films that can neither be taught nor faked seen and heard in the actors sucking of teeth, the casual and sometimes furious use of the word “backside,” the life-and-death seriousness with which the game Scrabble is approached, the polyester shirts that glimmer on the dancefloor, the sudden invocation of Mighty Sparrow in everyday speech (recall when Aunt Betty, Dolston, and Frank burst out singing “Jean and Dinah” in Mangrove), and the references to the all-saving Caribbean healer Vicks (as in the VapoRub). This list, abbreviated here, could stretch on infinitely in McQueen’s latest work if we let it. Such is the handiwork of a skilled filmmaker who treats the finer details of real Caribbean life with real respect. In Lovers Rock that authenticity is unmatched and, at times, unnamable yet still felt and most definitely heard. This is what the poet-critic Nathaniel Mackey might call a “telling inarticulacy.” Named for the smooth, romantic subgenre of reggae that emerged in the seventies-era, the film both unfolds and holds court on the dancefloor during a house party where pairs of lovers melt into each other getting lost in one another’s arms, getting lost in the night. Slow whines and sweet groves abound endlessly, passionately. In this film about the music of flirtation and romance, of seduction and swagger, lovers rock is not the backdrop to the main story. It is the story. Indeed, this is what makes this particular film so powerful: if you go looking for a plot you are certain not to find it, but if you listen to the sounds and sighs, the shouts and silence, then the story unfolds melodiously, magnificently.

“Lovers Rock is my musical,” said McQueen in a recent interview, “but it’s a different kind of musical. It’s a film about everyday Black experience and the importance of music to that experience both as an expression and a release, but there is almost a fairytale element to it. I wanted it to be transportive. So, the music had to work in a different way, to be integrated into the film in an organic way that I had never seen before.” Part of Lovers Rock filmic feat is how it defies traditional filmic conventions. The first twenty minutes solely set the stage for the night to come: people prepare pots of curry goat and saltfish, rearrange furniture, assemble sound systems, and select and discard outfits for an evening out. McQueen builds the anticipation slowly and steadily. No detail too small, no sound unimportant. A colossal undertaking about a collective, a community. Janet Kay’s 1979 “Silly Games” frames the film, a song which made her the first Black-British female to reach a #2 position with a reggae record. In preparation for the euphoric dance scene, McQueen blasted “Silly Games” and other songs through the speakers on set so his cast could dance. He also hired choreography Coral Messam to teach them how to whine and grind as couples. The result appears in the climax of the film – 38 minutes and 34 seconds in – when the camera pans not on a set of strangers at a house party, but a crowd turned congregation. This is church if ever there was. As the music fades this does not stop the voices from rising as people sing a capella style: “I’ve been wanting you / For so long, it’s a shame / Oh, baby. / Every time I hear your name / Oh, the pain / Boy, how it hurts me inside.” While they sing, McQueen does what he does best: film. His expert eye catches elbow a fly, hips a swaying, cheeks inseparable, and hands unstoppable. Black joy unscripted and uninterrupted. When asked about Lovers Rock, McQueen said, “Don’t forget, in those days, people used to work for the weekend. With this racism and oppression people had to deal with in the week – people lived for that Saturday.” Just like Mangrove, the threat of violence persists but not there, not that night, not during that dance. Just Black people, music, life.

McQueen’s Small Axe comes at a most peculiar time or perhaps exactly right on time in the wake of renewed interest in the Windrush generation as many people face threats of deportation and others are forcibly removed from the country and during a period of increased interest (for some) in the English monarchy (specifically, the whereabouts of Megan and Harry or the latest season of The Crown, for instance). McQueen’s filmic anthology stands as a tribute to a still understudied history that is well and alive; a memory that consists of so much more than solely accounts of the arrival of the Empire Windrush that docked at Tilbury in June 1948. Like any good – no superb – filmmaker, he trains our eyes and ears to look and listen for the music: the sonic lives of Black-British people in song and verse, in quotidian matters because as McQueen insists: all of it matters. Now and always.

***

Sasha Ann Panaram is an Assistant Professor of English at Fordham University. Her research focuses on twentieth and twenty-first century African American and Caribbean literature and culture, with a particular interest in women’s and gender studies, as well as slavery studies and performance studies

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

December 18, 2020

Black And Up In Arms

'Guns. They're as American as apple pie. They represent independence and self-reliance. But ... not so much if you're Black. On this episode of The Code Switch Podcast, we're getting into the complicated history of Black gun ownership and what it has to tell us about our present moment.'

Michelle Buteau, 'Survival of the Thickest'

'Comedian and actress Michelle Buteau is known for her roles in “Russian Doll,” "Always Be My Maybe," and her Netflix special, "Welcome to Buteaupia." In her book of essays, Survival of the Thickest , she brings her humor and insight to a wide range of topics, including dating, her early stand-up career, IVF, surrogacy, and chosen family.' -- All Of It

T Book Club: A Discussion on James Baldwin's 'Go Tell It on the Mountain' with novelist Ayana Mathis

'T’s Book Club consists of a series of articles and discussions dedicated to classic works of American literature. Here, our first (virtual) event, on James Baldwin’s 1953 novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” featuring the novelist Ayana Mathis — who first read the book as a teenager and has returned to it many times since — in conversation with T features director Thessaly La Force.'

December 17, 2020

DREAMWEAVERS: In / Conversation - Ming Smith and Arthur Jafa

'Check out episode 2 of UTA Artist Space's Dreamweavers series featuring artists Ming Smith and Arthur Jafa – in partnership with Lyft Entertainment. Arthur and Ming discuss how art can be used to address political and social issues. Directed by Sing J. Lee and Sylvia Zakhary.'

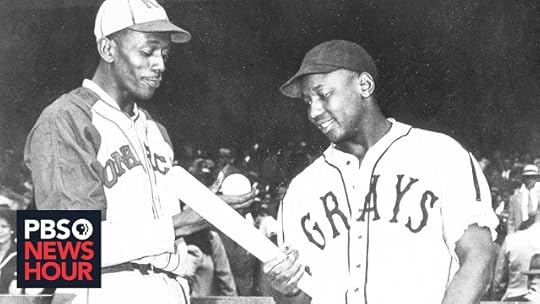

Negro Leagues are Elevated to Major League Status. What Does it Mean for Baseball?

'From 1920 to 1948, Black baseball players barred from the Major Leagues could only play in what were called Negro Leagues. As a result many of their accomplishments have been forgotten. But on Wednesday, Commissioner Rob Manfred said Major League Baseball was elevating seven Negro Leagues to Major League status. PBS NewsHour's John Yang spoke to ESPN's Howard Bryant to discuss.'

Robert Glasper Experiment - Everybody Loves The Sunshine (Tribute to Roy Ayers ft. Bilal)

"Ranked at the top of the charts of the most sampled jazz and soul musicians, Roy Ayers has inspired several generations of musicians, including Robert Glasper, who has made the art of covers a specialty with both volumes of his Black Radio project. With his Robert Glasper Experiment, a band with a strong connection between jazz and hip hop, he takes on the grand repertoire of the king of vibes. Half way through this fantastic performance, which also includes Pete Rock and Stefon Harris, the group are joined by the soul maestro Bilal, a former classmate of Glasper’s at the New School in New York.'

Stakes Been High: Mychal Denzel Smith on Life After the American Dream | Review by Mark Anthony Neal

Stakes Been High: Mychal Denzel Smith on Life After the American Dream

Review by Mark Anthony Neal | @NewBlackMan | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

When the group De La Soul released Stakes is High in 1996, it was the culmination, and thus the final break, with any claim they held to being stars. The trio was always ambivalent about their place in Hip-Hop’s hierarchy of fame – proclaiming six years earlier on their second outing, that De La Soul is Dead – but the stakes had changed for Hip-hop. It was no longer about party and bullshit or Assata and Malcolm for that matter, and its intimacy with mainstream capitalism was becoming more pronounced; Hip-Hop had become the American Dream. Stakes is High, released in July of 1996, philosophically anticipates the shooting deaths of Tupac Shakur and Christopher Wallace in the eight months after its release, and the rise of the shiny suit-rappers who replaced them on the music charts and continue reside there in an endless cycle of Lil’ This and Lil’ That. De La Soul disappeared into Hip-Hop’s briar patch, as producer 9th Wonder might describe it, returning to the regularness of everyday life, to be found only if you worked to do so.

But Stakes is High was also preoccupied with a Hip-Hop that had become the representation of the very fictions of super predators that were circulating in the culture at the time. The Crime Bill (The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994), authored by the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), of which then President Bill Clinton, future New York Senator Hillary Clinton and future President Joseph Biden were prominent members, the Republican Party’s Contract with America (or “contract on America”, as some would say; and we see you Ice Cube), and the O.J. Simpson murder trial all factor into the worldview that informed Stakes is High.

More than two decades later, similar tensions frame yet another iteration of Stakes Is High, writer Mychal Denzel Smith’s latest musing on “Life After the American Dream.” Constructed around the themes of delusions, justice, accountability and finally freedom – all rendered amorphous in the contemporary moment – Smith pressure tests “Truth, Justice, and the American Way,” ideals that are as fictionalized as the comic book hero for which such ideals were mantra. Smith is of a generation, or perhaps genre, of thinkers and writers in which there is a shared public intimacy associated with the failings of the State. A measure perhaps of the shifting terrain of punditry and the so-called democratization of opinion, if not expertise. It’s not that Black writers of previous generations didn’t feel the same disappointment or witness the same structural malfeasance – the short difference between Trump and Reagan is largely in the competency, or lack of in the case of Trump, of those charged to follow their orders – but that for the reader, in this moment of memes and 200-plus-character assessments, such insights read more familiar, or even mundane, than extraordinary.

Donald Trump is the book’s oft-cited whipping post, and deservedly so, though Smith comically recalls an early meeting with his editor, where they had “happily settled on an idea that would allow me an escape” -- from writing about Trump – yet “when I sat down to work on that book, the very first sentence I wrote had Trump’s name on it.” (181) Smith laments Trump’s early gaffe about Fredrick Douglass “getting recognized more, more”, which dominated Twitter for a few more news cycles, than it deserved, yet admits that he would rather Trump not know who Douglass really was so as not to “weaponize Douglass in service of state violence.” Here Smith is referencing Douglass’s oft-cited quote “If there is no struggle there is no progress”, which also appears on a placard outside Harlem’s Douglass Houses, yet as Smith observes, the fuller quote is not just some uplift theory to be viewed at the entrance of a federally subsidized housing project, but a fully throated call to resistance, which closes with “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” In this regard Trump is no better than most Americans as Smith writes, “the damage has already been done, the meaning of Douglass’s life and work already stripped away. He is as American as a Golden Retriever.” (31)

Smith is at his best highlighting the contradictions of White Liberals, comfortable with “rhetorical moves(s) with little consequence...that allows the speaker a perceived moral high ground.” (21) Smith points at the “never-Trump” and “not-my-president” types who are, at best, the “good liberal white folks” who “got good and mad and they had no idea how to go about to go about being mad.” (8) At worst these are the White folk who can claim that “they are not responsible for the current state of affairs because the president does not belong to them.” (21) Smith’s observations set-up of his take on the vacuous investments we all make in the power of the presidency: “The president is meant to be a part of an idealized nearly apolitical American nomenclature.” (23) For Smith the morally bankrupt contradictions of White liberals are embedded in so many of the symbols of American life, observing that “Babe Ruth is as much a symbol for the possibilities of whiteness under a system of segregation as he is some all-American beacon of greatness.”

In a thoughtful section of the book on the legacy of Shirley Chisholm and her more-than-symbolic presidential campaign in 1972, Smith is self-critical of his own investments in presidential politics. “The kind of country that would elect Shirley Chisholm as president would not need Shirley Chisholm to be president,” Smith writes, ultimately lamenting that “Shirley Chisholm was never going to be elected president. Donald Trump was inevitable.” (140-141) For Smith, Chisholm, who served New York's 12th congressional district for seven terms before stepping down in 1983, is a reminder that a “meaningful insurgency exists within us.”

Bill Cosby is also a target of Smith’s ire, and again rightfully so, though the former comic’s circumstances help frame a wide-ranging conversation about accountability that encapsulates observations about toxic masculinity (with all the obvious suspects), prison abolition, and violence against trans-women. Smith misreads the impetus for Cosby’s mythmaking in the creation of Cliff Huxtable (“it is the stuff of pure fantasy”). Cosby used the representational powers at hand to counter the myth-making – the pure fantasy – of White Supremacy that produced the Stepin’ Fetchits, George Jeffersons and Fred Sanfords. In some ways Lincoln Perry, Sherman Hemsley and Redd Foxx were no more complicit than Cosby was in creating Huxtable, but Smith is dead-on when he makes the finer point that Cosby deployed the conflation of Cosby and Huxtable to obscure, and thus further, his roles as sexual predator and race-traitor – if you consider the ideological pogrom he waged on the Black poor, both with the Cosby Show, and more alarmingly, when the show was no longer in production.

The chapter on accountability feels muddled or even constricted, as if it should have been the sole focus of the book itself, yet there are gems, like Smith’s observation that “there exist little of the cultural curiosity with regard to rapists as there is serial killers.” (118) Smith offers the latter point to make a larger one: “We have essentially conceded that rape, or at the very least the potential of rape, is part of our societal makeup,” explaining, in part, the ambivalence around celebrity predators in some sectors of American society (including MAGA hat wearers), even in the era of #MeToo. (119).

On the question of prison abolition, Smith writes “prison is not a means of preventing violence but shifting it out of sight from polite society.” (132) Smith is equally sharp when discussing violence against trans women, acknowledging that “I don’t believe it is any accident that in recent years, as gender constructs come under scrutiny and traditional masculinity in particular has been met with condemnation, that the homicide rates for trans women have reached record highs.” Smith illuminates the connection between the lives of trans women and abolition, asserting “Survival work, which is largely understood as sex work or the drug trade, is illegal work which then puts black trans women at greater risk of being targeted by law enforcement, its own form of violence.” (128) Arguing that the decriminalization of “survival work” would enhance the lives of trans women, Smith admits that such efforts would “leave one major threat unaddressed: the fragility of cis men.” (129)

Smith is more hopeful than many of his peers who are enthralled with Afropessimism, yet there is a ringing reservation in Smith’s words when he writes, “nothing will be resolved when Bill Cosby dies in jail. It will still take an hour to get from Bushwick to Crown Heights” – two neighborhoods in Brooklyn – “unless we set the intention to create a different path.” (135) I’ve often felt that Smith’s public writing only scratches the surface of all that he wants to say or can say, and I feel that way about Stakes is High. In that regard I’ll borrow a riff from Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who in writing about the great Greg Tate almost thirty years ago, implored readers and critics to “keep this nigga boy writing”; I wish the same for Mychal Denzel Smith.

***

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African & African American Studies at Duke University. He is the author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and the forthcoming Black Ephemera: The Challenge and the Crisis of the Black Musical Archive.

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

December 16, 2020

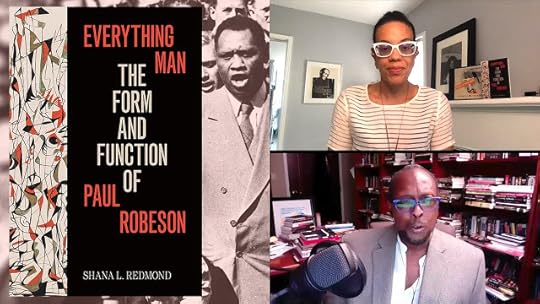

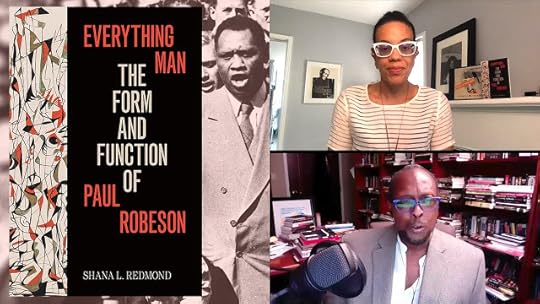

Left of Black S11 · E8 | Dr. Shana L. Redmond on the Life and Impact of Paul Robeson

Who was the first Black movie icon? Many would argue in favor of the unparalleled and unmatched Paul Robeson. Known for his immense presence on the silver screen and his baritone singing voice, Robeson also shook up the status quo of his day as political activist for Civil Rights drawing praise and scrutiny on the world stage. Dr. Shana L. Redmond, Professor of Musicology and African American Studies at UCLA, sits with Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal to discuss her latest publication, Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson, published by Duke University Press.

Who was the first Black movie icon? Many would argue in f...

Who was the first Black movie icon? Many would argue in favor of the unparalleled and unmatched Paul Robeson. Known for his immense presence on the silver screen and his baritone singing voice, Robeson also shook up the status quo of his day as political activist for Civil Rights drawing praise and scrutiny on the world stage. Dr. Shana L. Redmond, Professor of Musicology and African American Studies at UCLA, sits with Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal to discuss her latest publication, Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson, published by Duke University Press.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers