Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 253

January 26, 2021

Bevy Smith on Reinventing Yourself

'Bevy Smith, host of Sirius XM’s Bevelations, joins All Of It to discuss her new book about career reinvention titled, Bevelations: Lessons from a Mutha, Auntie, Bestie.'

Troubling Findings Revealed By NPR Investigation On Police Shootings Of Black People

'Police officers have fatally shot at least 135 unarmed Black men and women in the U.S. since 2015, according to an NPR investigation. Here & Now's Callum Borchers speaks with Cheryl W. Thompson about her team's findings.'

January 24, 2021

Left of Black S9:E25: Vernacular Archives of Afro-Asia with with Tao Leigh Goffe (The Lost Episodes)

Left of Black co-host Sasha Panaram (@SashaPanaram) is joined in the studio by American Studies scholar, Tao Leigh Goffe (@taoleighgoffe). Goffe is an Assistant Professor of Africana and Feminist, Gender, Sexuality Studies at Cornell University. She received her PhD in American Studies from Yale University in 2015. Her work examines the vernacular cultures that emerge from the histories of imperialism, migration, and globalization. Her first book, A History of Touches: Vernacular Archives of Afro-Asia assembles a sensate archive of recipes, playlists, photo albums, and ghost cultures. Her work has been published in Small Axe, Anthurium, and Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas.

Left of Black S9*E24: Jason Moran on James Reese Europe, The Great Migration and Living in Harlem (The Lost Episodes)

Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) is joined in the studio by musician Jason Moran (@morethan88). “Jason Moran is one of modern music’s most vital forces. Through a series of ambitious projects meant to bring jazz to a wider audience — such as the 2007 Duke Performances commission In My Mind, which reimagined Thelonious Monk’s 1959 Town Hall performance — Moran has become one of the most sought-after pianists and bandleaders in jazz today. With frequent daring nods to funk, hip-hop, and contemporary composition, Moran has expanded jazz’s stylistic reach and given it new vitality. Now a label head and the artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center, Moran is the form’s ‘greatest young conceptualist,’ as Jazz Times exclaimed.”

Left of Black: S9:23: Tony Award Nominee Camille A. Brown and Grammy Award Winner 9th Wonder in Conversation (The Lost Episodes)

'In this special episode of Left of Black host Mark Anthony Neal (@NewBlackMan) and Grammy Award Winning Producer 9th Wonder (@9thWonder) are joined by choreographer, dancer, and director Camille A. Brown (@CamilleABrown). Brown was visiting Duke University as part of her year-long residency at the University with Duke Performances.'

January 23, 2021

Actor Wendell Pierce On The Role Of Art In Advancing Social Progress

'Here & Now's Tonya Mosley continues her conversation with actor Wendell Pierce about the significance of his work in HBO's The Wire given recent calls for police reform and the role of art in advancing social progress.'

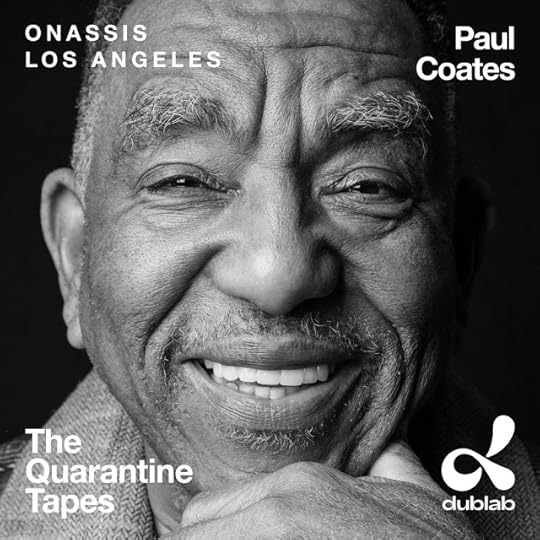

The Quarantine Tapes 149: Paul Coates

“Western language doesn’t give us that space in between. Either you hope and you’re optimistic or you’re pessimistic. There’s a clear either white or black, there’s no gray in between.”

'Guest host Walter Mosley is joined by W. Paul Coates on episode 149 of The Quarantine Tapes. Coates is a publisher and the founder of Black Classic Press. Moseley opens the conversation with a question about what hope Coates is finding in this moment. This leads into a deep and generative discussion about the definition of hope. They discuss Coates’s history with the Black Panthers, Medgar Evers, and Walter’s writing in their attempts to parse the difference between each of their understandings of hope, struggle, and optimism.'

Religious Social Ethicist Wylin Wilson on Religion, Health, and the African American Community

'Religious Social Ethicist Wylin Wilson on religion, health, and the African American community in the rural south.' -- Harvard Divinity School

January 21, 2021

“I Wonder When I Die Will He Give Me Receipts?”: A Review of Marcus J. Moore’s 'The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America'

“I Wonder When I Die Will He Give Me Receipts?”: A Review of Marcus J. Moore’s The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America

by Tyler Bunzey | @T_Bunzey | NewBlackMan (in Exile)

When it was announced that MF DOOM, the mysterious masked hip-hop wordsmith, passed earlier this year, the hip-hop community had to mourn a figure who many never knew at all. The December 31st announcement, coming two months after his death, initiated a great outpouring of grief and memorializing. DOOM, after all, was an artist’s artist, forgoing conventions of rhyme scheme, flow, vocal attack, lyrical content, and performance practice to constantly push at the edges of how hip-hop can look and sound. The Mad Villain was infamous for his privacy, constantly wearing a mask and famously sending DOOM imposters in his stead at live performances, a privacy that is often attributed to DOOM’s loss of his brother and co-performer Subroc in a car accident. The carefully curated privacy of DOOM’s life and death poses an impossible question: how do we mourn the death of a celebrity whose life we never really knew?

DOOM is in good company. Many Black hip-hop artists remain tight lipped about both their work and their personal life, from Lauryn Hill to Andre 3000 to Yasiin Bey to Kendrick Lamar, likely in order to evade the capture of American celebrity culture and the totalizing hold that the hip-hop industry has on artists’ lives. Hip-hop culture, in particular, presents a cult of authenticity through an artist’s persona. When combined with the cult of celebrity, this authenticity culture encourages artists to keep it real by exposing the banality of every aspect of their lives (think Cardi B’s live streams, MTV Cribs, the press requirements of record labels, etc.). When artists are able to evade this kind of capture, they create a kind of “problem”: how do we as fans remember the lives of public personas whose privacy was as remarkable as their performances?

Marcus J. Moore addresses this kind of biographical “problem” in his new examination of the life of Kendrick Lamar: The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America (2019). Frankly, I was a bit doubtful of a biography considering a figure that appears more as void than presence in the American popular sphere. While those of us making GOAT lists in internet debates can’t get Kendrick Lamar’s name out of our mouths, he rarely actually gives us every day gossip to debate. He is a careful artist, curating only a relative handful of performances and interviews alongside his recorded repertoire. He is a notorious recluse and is deeply protective over his image and legacy. As such, how could anyone not in his immediate circle claim some kind “insider’s view” in order to write a biography? When Kendrick is so protective of his life, how could someone write about anything but his music? At this point, what is there actually to discuss about the life and times of Kendrick Lamar in the form of the biography?

Moore gracefully sidesteps some of the conventional trappings of biographical writing, avoiding tabloid-like titillation for a more measured examination of Kendrick’s recorded work. Moore doesn’t expose what it is like to live with Kendrick Lamar Duckworth. Rather, he exposes what it means to live with Kendrick Lamar’s music. While he doesn’t shy away from talking about the enigmatic rapper’s life story, Moore always returns to the music itself. To this end, The Butterfly Effect melds methods, weaving a narrative of Kendrick’s music that reads like liner notes remixed through golden age hip-hop journalism.

The result of Moore’s effort is a well-woven tale of Kendrick’s reception that is as equally ready for a superfan to soak up hidden gems about the production of his oeuvre as for a newcomer to Kendrick trying to get a sense about what the hype is all about. More remarkable than his musical meditations, however, is Moore’s articulation of how Kendrick Lamar reignited the centuries-long tradition of Black protest music in the mid-2010s. Certainly, Kendrick makes elegant, innovative music. But more significantly, he has created anthems for a generation of activists in need of new songs to rally around. The Butterfly Effect demonstrates how Kendrick’s musical excellence is only activated alongside his Black excellence, and the biography directly engages this reception while maintaining respect for this generational artist’s carefully curated privacy.

The biography formally follows Lamar’s career in its chronology, stopping for entire chapters to luxuriate in the details of production for certain albums or the political flashpoints of his performances. Moore’s first chapter, however, does the fundamental work of setting up the mythology of Kendrick Lamar that animates the book’s treatment of his career. The first chapter celebrates the internal tensions of Lamar, narrating the origins of survivor’s guilt, industry underappreciation, collaboration, and his remarkable pen game that defines his work. This initial biomythography—to riff on Audre Lorde—enables the reader to understand the slow development of Kendrick as an emcee, which Moore details in Chapters 2 and 3. He paints Kendrick as a slow burner, carefully observing his elders and fellow artists to curate a persona, performance practice, and penmanship that eclipsed his peers in complexity and maturity. Moore then dives into what amounts to detailed narrative liner notes for each of Lamar’s celebrated albums (with an entire chapter dedicated to the underappreciated album/mixtape Section.80, which this fan was thrilled about). These chapters spend equal time discussing production processes and considering the emotive and psychological purposes of Lamar’s composition. They serve as sort of psychographic annotations, considering the material alongside the spiritual and emotional in Kendrick’s process.

If Moore had stopped there, he would have created a biography that read like a carefully curated book length RapGenius annotation—a laudable feat. However, Chapters 7 and 8 introduce the spirit of this biography: Kendrick Lamar’s generational importance to Black America. In Chapter 7, Moore argues that Lamar’s “Alright” “was a middle finger to the establishment and the same law enforcement that killed Eric Garner, Oscar Grant, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, and so many before them” (184). “Alright,” in Moore’s treatment, becomes the “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” or the “Do the Right Thing” for my generation, giving voice to the thousands of on-the-ground organizers around the country that forced America to confront its ugly and persistent anti-Black violence throughout the latter term of Obama’s tenure in office. If Lamar’s “Alright” (re)ignited Black America against specifically the police’s anti-Black violence, Chapter 8 considers how Lamar’s 2016 Grammy Awards performance addresses the explicit anti-Black violence that would become the signature of Trump’s era. Moore suggests that this performance placed Kendrick on the “Mount Rushmore of hip-hop,” elevating him to the likes of a “once-in-a-generation talent” that has the power to tap into the political consciousness of our time (221). These chapters are the beating heart of Moore’s analysis, and they make a remarkably convincing case for Kendrick’s ascension as he “helped Black America soundtrack its way to a higher consciousness” (224).

Through this care and attentiveness toward the reception of Lamar’s work, The Butterfly Effect models ethical cultural criticism for those of us who study and examine the artists who make and mark our contemporary era. Not only does this book provide fans and newcomers alike with a robust cultural analysis of the figure of Kendrick Lamar, it also takes the temperature of America in its feverish last five years. Moore’s deep sensitivity toward Lamar’s privacy creates a desensationalized but celebratory account of Lamar’s life as he has given it to us thus far. Moore’s critical treatment hopefully will help Kendrick wonder a little less whether or not he will receive his receipts, or his accolades, when he dies, as he has mused publicly in his music. With the death of figures like DOOM this year, we are reminded that we shouldn’t wait to give artists their flowers until after their deaths. The Butterfly Effect prods us, as critics, fans, and scholars, to develop this kind delicate and mindful cultural criticism while artists are still with us, simultaneously upholding the privacy of beloved creatives and honoring their contributions that help us dismantle a world pockmarked by anti-Black violence.

+++

Tyler Bunzey is Visiting Assistant Professor of Cultural Studies at Johnson C. Smith University / Ph.D. candidate at UNC-CH studying 20th c. African-American lit and hip-hop. Follow him on Twitter: @t_bunzey

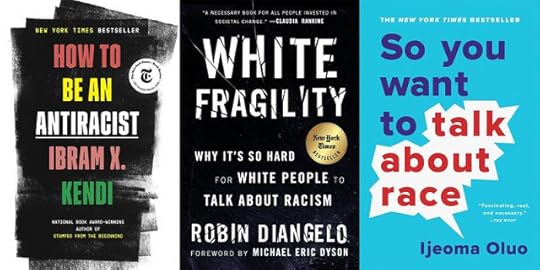

Are People Still Turning to Anti-Racist Books?

'From Dr. Ibram X Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist to Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility to Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race?, books about racism and antiracism flew off the shelves at libraries and bookstores across the U.S.—as many white people started grappling with the country’s history of systemic racism, some for the first time. Now, more than six months later, have people actually followed through with reading these books? For that and more, The Takeaway spoke to Hannah Oliver Depp, owner of Loyalty Bookstores in Washington, D.C. and Silver Spring, Maryland, and Katherine D. Morgan, a freelance writer and former bookseller at Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon.'

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers