Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1063

August 29, 2011

"Where Dey At?": Bounce and the 'Sanctified Swing' in Post-Katrina New Orleans

"Where Dey At?": Bounce and the 'Sanctified Swing' in Post-Katrina New Orleans

by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackMan

In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the failure of the levees in New Orleans, there were many high profiles efforts to raise awareness about the cultural legacy of New Orleans. Many of those efforts centered on the exaltation of New Orleans Jazz, with many events aimed at providing shelter and support for Jazz musicians dispersed by the tragedy. New Orleans Jazz seemed the most important resource to be protected in the months after Katrina, more so than the people who made the city such a vital and important, ever evolving cultural outpost. Lost in the focus on New Orleans Jazz—arguably one of the nation's most important cultural exports—are other forms of musical expression that were and continue to be crucial to the survival and spirituality of New Orleans and its citizens, including those who have yet to return.

Though Jazz was a critical component of Black political discourse and intellectual development throughout the 20th century—jazz musicians like John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln are some of the most resonate examples of creative intellectuals—New Orleans Jazz is often depicted as being tethered to some imagined past, in which race relations and the power dynamics embedded in them were far more simplistic.

Indeed recent films like The Princess and the Frog and The Curious Case of Benjamin Buttons the television series Treme (despite it's progressive political critiques) contribute to a nostalgic view that New Orleans Jazz as a dated, static musical form that offers an "authentic" alternative to more commercially viable forms of popular music like rap and R&B music. Much of this has to do with the relationship between New Orleans Jazz and the leisure and tourist industries that were so vital to the city's economy. In this context, mainstreams desires to save New Orleans Jazz and to protect its musicians are less about strengthening the links between Jazz and Black cultural resistance—a resistance that historically fermented in New Orleans—but maintaining the economic vitality of what Johari Jabir calls the "theater of tourism" in which Black bodies are rarely thought of as citizens but laborers, servants and performers.

In the introduction to the book, In the Wake of Hurricane Katrina: New Paradigms and Social Visions, scholar Clyde Woods places New Orleans Jazz in a much broader context, as part of what Woods has famously described as a "Blues tradition of investigation." As Woods notes in his essay, "Katrina's World: Blues, Bourbon and the Return to the Source," historically the city of New Orleans and the region was "latticed with resistance networks that linked enslaved and free blacks with maroon colonies established in the city's cypress forests swamps."

Though Mahalia Jackson came to prominence in Chicago, the legendary Gospel singer was born and raised in New Orleans's Lower Ninth Ward. Jabir suggest that one of the reasons that Jackson is rarely thought about with regards to New Orleans has to do with "the ways the canon of New Orleans music is recognized exclusively through the lenses of blues and jazz." More importantly Jabir writes, in his essay "On Conjuring Mahalia: Mahalia Jackson, New Orleans, and the Sanctified Swing," the impact of New Orleans music on Jackson—what she called "a rhythm we held on to from slavery days"—allowed her to bring an element of "swing" (associated with Jazz) to the decidedly anti-secular Gospel tradition of the mid-20th century.

Using the example of Jackson's often-recalled performance of "Didn't It Rain" at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival (for which she was heavily criticized by the "true believers"), Jabir suggest that Jackson's performance of the song anticipates the Hurricane Katrina disaster that occurs more than thirty years after her death. Jabir is not so much suggesting that Jackson had the capacity to tell the future—though the history of the region might suggest otherwise—but that the "sanctified swing" that marked her music and others like Duke Ellington (or Wynton Marsalis if you listen to In This House, On This Morning) is "a heartbeat, a pulse driven by a persistent rhythm" adding that "if music were a living organism, the pulse would hold the music steady, sustaining life in the midst of various rhythms." Ultimately, according to Jabir, Jackson's performance of "Didn't It Rain" is a "tenacious hope that finds the singer describing the disaster, accepting it, and living in spite of it"—a gift to those who would come well after Jackson who could grab hold to the "sanctified swing" when faced with their own survival.

Even less regarded by the mainstream consumers of New Orleans music is rap music, as most popularly represented by figures such as Lil' Wayne, Juvenile, Master P, Mystical and others. Yet Woods suggest that even Hip-Hop culture in New Orleans is an articulation of the "Blues tradition of investigation" particularly in the form of the regionally specific genre of Bounce music. The New York Times recently chronicled a contemporary strain of Bounce known as Sissy Bounce, though the genre's roots go back to the late 1980s. It was the 1990 song "Where Dey At" by MC T. Tucker that helped give the style some prominence beyond New Orleans. Woods connects Bounce to earlier forms of New Orleans musical expression, citing the refrain "Fuck David Duke, Fuck David Duke, I say, I say" from "Where Dey At" (in response to the KKK leader who was elected to the Louisiana legislature in 1990), as harkening back to "critiques of the plantation bloc found in the Calinda song and dance tradition perfected on Congo Square [the "birthplace" of Jazz] during the 18th century.

In her essay, "'My Fema People': Hip-Hop as Disaster Recovery in the Katrina Diaspora" Zenia Kish pushes the connection between Bounce and New Orleans Hip-Hop more explicitly. As Bounce created an autonomous New Orleans based riff on Hip-Hop, it informed Hip-Hop's responses to Katrina including Mia X's "My Fema People," 5th Ward Weebie's "Fuck Katrina (The Katrina Song)" and The Legendary K.O.'s now famous "George Bush Doesn't Care About Black People." Though mainstream rap artists like Jay Z, Lil Wayne, Kanye West, Mos Def, and Juvenile ("Get Your Hustle On"), offered responses to Katrina, Kish suggest that tracks like those from Mia X and 5th Ward Weebie offered a "collective first-person perspective" of the "frustrations, humiliations, and pleasures grounded in specifically local knowledge of the multiple socioeconomic disasters that intersected with Katrina."

As so many of the Power brokers in New Orleans and the State of Louisiana draw on a distorted vision of New Orleans music, to cultivate a connection to an imagined past, Bounce, the "sanctified swing" and the "Blues tradition of investigation" all conspire to keep the "people" of New Orleans—what I call the Katrina-politans in reference to Taiye Tuakli-Wosornu's concept of Afropolitans (Africans of the world)—connected across time, history, space and place.

Published on August 29, 2011 07:02

August 27, 2011

Michael Eric Dyson: In the Name of King

In the Name of King by Michael Eric Dyson | Time.com

A year ago, as my interview wrapped with President Obama in the Oval Office, he led me to the bust of Martin Luther King Jr. by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Charles Alston that he had installed near a bust of Abraham Lincoln. Obama's gaunt visage creased in delight as we gazed in silent awe on the face of a man the two of us baby boomers have acknowledged as a great inspiration. In the near future Obama will participate in a far more public recognition of the martyr's meaning when he speaks at the dedication of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall. King becomes the first individual African American to occupy the sacred civic space dominated by beloved Presidents like George Washington and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. King's image on the Mall is a sturdy reminder that his story, and the story of the people for whom he died, helped to rescue American democracy and make justice a living creed. King's memorial is even more impressive because his statue rises 30 ft. high on a direct line between the likenesses of Jefferson and Lincoln, dwarfing those memorials by 11 ft. — it is one of the tallest on the Mall. Even in death, King is still breaking barriers.

Obama's words on the Mall will be framed by a bitter dispute over King's legacy in black America and its revelation, or distortion, in leaders like Al Sharpton and Obama himself. Sharpton has emerged as an improbable leader of black America and a more improbable defender of Obama, a status that challenges his prophetic credentials in some quarters. Sharpton tangled on radio in 2010 with television host Tavis Smiley over Sharpton's contention that Obama shouldn't "ballyhoo 'a black agenda.' " Earlier this year on cable television, Princeton professor Cornel West shouted at Sharpton that the voluble minister could be "easily manipulated by ... the White House" to become the "public face" of entrenched Wall Street and corporate interests.

If Smiley and West fear that Sharpton has become Obama's pal and not his prophet, they seek to take up the slack and press Obama about his neglect of blacks and the poor at every chance. Their relentless criticism has earned them rebukes from many black folk and the enmity of radio host Tom Joyner, who once championed the duo, while Joyner's colleague Steve Harvey derided the pair as "Uncle Toms." These vicious attacks didn't stop Smiley and West from hitting the road recently for a 16-city "poverty tour" to spotlight the invisible poor in the name of King. Unfortunately, the political and racial circumstances that gripped their crusade drew more press to them than to the poor. Obama, Smiley and West and Sharpton all claim King's example. Who makes the most of it is a complicated story.

It is both fitting and ironic that Obama presides over the cementing of King's status as an icon in the national political memory. Obama's historic presidency is unthinkable without King's assassination and the black masses' bloodstained resistance to racial terror. Obama embraced King's rhetoric of justice during his presidential campaign while eschewing his role as prophet. Presidents uphold the country; prophets often hold up an unflattering mirror to the nation. King may now be widely regarded as a saint of American equality, but he often had to criticize his nation's politics and social habits to inspire and, at times, to force reform. He helped to make America better by making it bend to its ideals when it got off course as its loving but unyielding prophet. Had he lived, King would have certainly hailed Obama's historic feat even as he took issue with some of the President's policies toward black and poor people. It would have been principled criticism rooted in an obsession with improving the lives of the vulnerable. To paraphrase Obama's favorite film, The Godfather, King's arguments would have been business, not personal.

The same doesn't appear to be true for Smiley and West. Smiley openly criticized candidate Obama for not attending his State of the Black Union gathering in 2008, and many believe the slight stuck in Smiley's craw and has led him to blast the President ever since. The notion is swatted away by Obama's appearance on videotape at Smiley's 2009 event. Smiley criticized Presidents Clinton and Bush too, though, it must be noted, not as visibly or vocally as he's done with Obama. Smiley has admitted that Clinton seems to him like a fourth brother, a closeness that may have tempered his criticism of the former President. No such restraints keep the media marvel from an intrepid criticism of Obama.

The same is true for West, a brilliant intellectual who has even more aggressively aired his grievances, calling Obama "a black mascot of Wall Street oligarchs and a black puppet of corporate plutocrats." It proved a pattern: West's trenchant analysis of Obama's policies is often sullied by needless name-calling. West's gripes are sometimes disturbingly personal and laced with macho psychoanalysis and peals of wounded ego: disgust with Obama because West and his family couldn't get Inauguration tickets (West's complaint that the bellman who carried his bags at a Washington hotel could get a ticket when he couldn't undercuts his noble advocacy for working and poor folk); the perception that Obama was afraid of a "free black man" like West (a belief that may be unfounded in light of Obama's in-your-face dressing-down of West after a presidential address in Washington); and the hostility West unleashed when he said that he wanted to "slap [the president] on the side of his head" after Obama had ambushed and embarrassed him in their D.C. spat. West's loving heart may belong to King at his best, but his lashing tongue belongs to Malcolm X at his worst. His legitimate criticism is lost in the mix. (See photos of the civil rights movement, from Emmett Till to Barack Obama.)

Sharpton's evolution may put him closer to King the presidential dealmaker than critics of the supremely gifted leader and newly minted talk-show host have so far let on. Sharpton cut his prophetic teeth on urban protest as an unpolished version of his idol Jesse Jackson, courting controversy and combatting police brutality against poor and working-class blacks. The accoutrements of his guerrilla resistance included the jogging suit, the lavishly styled perm, the bullhorn and the shrilly amplified mantra "No justice, no peace." Sharpton's odyssey from stubborn outsider to ultimate insider is documented in the shift to well-tailored suits and a more modest coif. Sharpton scaled the ire of the white masses and the embarrassment of the black elite to become a savvy power broker with unparalleled access to Obama. It remains to be seen what Sharpton makes of his opportunity, but the fact that he has it doesn't mean he should be condemned as a sellout. In fact, his greatest contribution may be not what he makes happen but what he keeps from happening by being at Obama's ear or elbow.

Constructive criticism of Obama is healthy; demanding that he pay attention to the needs of poor folk and people of color is righteous. Confusing personal beef with principled criticism only ends up undermining the high aims of social prophecy. When critics call Obama names, they sound no better than the bigots who wish him failure and death. We ought to remember that as we celebrate a man who was a selfless prophet and soldier of truth before he was murdered and turned into a saint and statue.

***

Michael Eric Dyson, a Georgetown professor and contributing editor of TIME, is author of April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Death and How It Changed America. Follow him at @MichaelEDyson.

Published on August 27, 2011 09:41

August 26, 2011

Emmett Till and Dr. King's Memorial

Emmett Till & Mamie Till Mobley

Emmett Till and Dr. King's Memorial by Eddie Glaude, Jr. | HuffPost BlackVoices

Emmett Till was murdered on August 28, 1955. They found his body horribly mangled at the bottom of the Tallahatchie River with a cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. Till had dared to break one of the sacred rules of the Jim Crow South. He "flirted" with a white woman. He was only fourteen years old.

Emmett Till's mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to have an open-casket funeral. She wanted everyone to see what they had done to "her baby." The Chicago Defender reported that over "250,000 people viewed and passed by the bier of little Emmett Till ... All were shocked, some horrified and appalled. Many prayed, scores fainted and practically all, men, women and children wept."

On September 15th, 1955 Jet Magazine published, unedited, the images of Emmett Till. Black America was stunned. For some, this was the first visual image of the brutality of American racism. For others, the dead body of Till only confirmed the disease at the heart of the United States. America was sick. And Emmett Till was to become the sacrificial lamb, which sparked the modern Civil Rights Movement that sought to heal the nation.

What did Mamie Till Mobley want us to see when she decided to leave open her baby's coffin? What was she memorializing at that moment? Obviously, her decision called attention to the brutality of American racism. But I am convinced that she wanted to make visible all of those victims of American hatred who remained invisible. The nameless black bodies that lined the bottom of the Tallahatchie River and the spirits that were defeated daily by the systemic and dehumanizing experience of white supremacy were all captured in the brutally disfigured face of a murdered fourteen-year old boy. Perhaps she wanted that image to haunt the nation -- to force us to remember those who reside in the shadows. Those images defined a generation. And they, at least for me, continue to haunt.

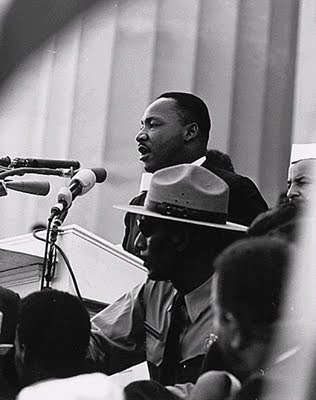

On the exact same day, eight years later, an estimated 250,000 people engaged in an historic demonstration before the Lincoln Memorial for civil rights and economic justice. And it was here that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. In some ways, that speech stands as a third "founding" of the nation. Just as President Lincoln's second inaugural offered a revision of the revolutionary beginnings of America, Dr. King's words expanded the very idea of American democracy in which the promises of freedom and justice would be extended to its entire people.

We have now honored Dr. King with a national memorial. But what are we to see and to remember when we visit this place? How are we to understand its connection to the death of Emmett Till?

That memory is also lost as those who claim Dr. King's inheritance use the anniversary of the March on Washington to project themselves as leaders. They urge us to engage in rote marches, while one after another wraps themselves in the shroud of Dr. King's prophetic sacrifice. All the while, suffering remains unseen as they revel in newfound access to the corridors of power.

In some ways, how we remember the black freedom struggle today is destroying parts of our collective memory. America's racist past has become too neat and clean; our dead have been ushered off stage. All the while Rush Limbaugh, Senator Tom Coburn, and others trade in the languages of its insidious offspring. And the structural legacy of racism continues, despite claims of personal responsibility, to deny opportunity to a significant portion of the American population.

Americans, especially African Americans, must not walk through the King national memorial without remembering our dead, without calling the names of those we know and acknowledging the nameless souls who sacrificed for a more just world.

This is why we have to return to the open casket of Emmett Till. How we remember our dead informs how we struggle on behalf of those who live in the shadows. Mamie Till Mobley taught us this lesson. She declared boldly, even after burying her child, that she did not have time to hate -- that she would pursue justice for the rest of her life. That open casket was about justice; those images of Emmett Till were to remind us about the never-ending fight for justice. And if we revel in the simple fact that Dr. King's image stands among the memorials in Washington, D.C. without remembering the fight for justice today then we have been taken in by sounding brass and tinkling cymbal, and we've turned our backs on our dead.

Follow Eddie Glaude, Jr., Ph.D. on Twitter: www.twitter.com/esglaude

***

Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. is currently the William S. Tod Professor of Religion and chair of the Center for African American Studies at Princeton University. He is the author of several books. His latest book, In a Shade of Blue: Pragmatism and the Politics of Black America, has been characterized as "a tour de force."

Published on August 26, 2011 15:29

Imani Perry on the Significance of the MLK Memorial

The Michael Eric Dyson ShowFriday August 26, 2011

Imani Perry on the Significance of the MLK Memorial

The Michael Eric Dyson ShowFriday August 26, 2011

Imani Perry on the Significance of the MLK Memorial

Despite the threat from Hurricane Irene, visitors are beginning to gather on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to celebrate the opening of the new memorial dedicated to fallen Civil Rights Leader Martin Luther King Jr. But how diverse is this group? A recent USA Today/Gallup poll showed that seven out of 10 Americans are interested in visiting the new MLK memorial, but that number has some huge racial disparities. We talk to Dr. Imani Perry, professor in the Center for African-American Studies at Princeton University, to help us make sense of those numbers and to explore the larger significance of the MLK memorial.

[image error]Listen Now: Dr. Imani Perry

Published on August 26, 2011 14:36

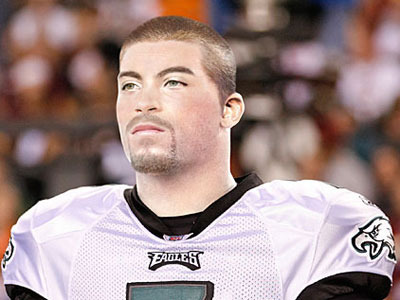

What Happened to Post-Blackness? Touré, Michael Vick and the Politics of Cultural Racism

What Happened to Post-Blackness? Touré, Michael Vick and the Politics of Cultural Racism by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

In the current issue of ESPN: The Magazine, Touré, author of the forthcoming Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness?: What It Means to Be Black Now, jumps into the discourse about race, Michael Vick, and his larger significance as we enter the 2011 football season. In "What if Michael Vick were white?", which includes the requisite and troubling picture of Vick "in whiteface" ("Touré says that picture is both inappropriate and undermines his entire premise") Touré explores how different Vick's life on and off the field might have been if he wasn't black.

While acknowledging the advantages of whiteness and the privileges that are generated because of the structures of American racism, Touré decides to focus on how a hypothetical racial transformation would change Vick's life in other ways. "The problem with the 'switch the subject's race to determine if it's racism' test runs much deeper than that. It fails to take into account that switching someone's race changes his entire existence.," notes Touré. Among others things, he asks "Would a white kid have been introduced to dogfighting at a young age and have it become normalized?" The answer that Touré seems to come up with is no, seemingly arguing that his participation in dog fighting results from his upbringing "in the projects of Newport News, VA" without a father (he also argues that his ability to bankroll a dogfighting enterprise came about because of his class status that resulted from his NFL career, an opportunity that came about because he like "many young black men see sports as the only way out").

Here, Touré plays into the dominant discourse that links blackness, a culture poverty and presumably hip-hop culture to dogfighting, thereby erasing the larger history of dogfighting. According to Evans, Gauthier and Forsyth (1998) in "Dogfighting: Symbolic expression and validation of masculinity," dogfighting "represents a symbolic attempts at attaining and maintaining honor and status, which in the (predominantly white, male, working-class) dogfighting subculture, are equated with masculine identity." Although the popularity of dogfighting has increased within urban communities, particularly amongst young African Americans, over the last fifteen years it remains a sport tied to and emanating from rural white America.

It should not be surprising that six (South Dakota; Wyoming; West Virginia; Nevada; Texas; and Montana) of the seven states with the lowest rankings from the Humane Society are states with sizable white communities (New York is the other state). Given that dogfighting is entrenched and normalized within a myriad of communities, particularly white working-class communities within rural America, it is both factually questionable and troubling to link dogfighting to the black community.

Touré moves on from his argument about a culture of poverty in an effort blame Vick's family structure for his involvement in dog fighting "Here's another question: If Vick grew up with the paternal support that white kids are more likely to have (72 percent of black children are born to unwed mothers compared with 29 percent of white children), would he have been involved in dogfighting?" Having already taken this argument apart in regards to Colin Cowherd's recycling of the Moynihan Report, let me recycle some of my own words:

The idea that 71% of black children grow up without fathers is at one level the result of a misunderstanding of facts and at another level the mere erasure of facts. It would seem that Mr. Cowherd is invoking the often-cited statistics that 72% of African American children were born to unwed mothers, which is significantly higher than the national average of 40 %. Yet, this statistic is misleading and misused as part of a historically defined white racial project. First and foremost, child born into an unmarried family is not the same is growing up without a father. In fact, only half of African American children live in single-family homes. Yet, this again, only tells part of the story. The selective invoking of these statistics, while emblematic of the hegemony of heterosexist patriarchy, says very little about whether or not a child grows up with two parents involved in their lives. According to the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study , a sizable portion of those children born to single mothers are born into families that can be defined as "marriage like." 32% of unmarried parents are engaged in 'visiting unions" (in a romantic relationship although living apart), with 50% of parents living together without being married. In other words, the 72% says little about the presence of black fathers (or mothers for that matter). Likewise, this number says very little about the levels of involvement of fathers (and mothers), but rather how because of the media, popular culture and political discourses, black fatherhood is constructed "as an oxymoron" all while black motherhood is defined as "inadequate" and "insufficient."

In other words, as illustrated Roberta L. Coles and Charles Green, The Myth of the Missing Black Father , "non-residence" is not the same as being absentee; it says nothing about involvement and the quality of parenting. As such, the efforts to links the myths and stereotypes about black families to explain or speculate about Michael Vick's past involvement (what is the statue of limitations of writing on this subject?) with dogfighting does little beyond reinforcing scapegoats and criminalizing discourses.

The argument here that race matters in Michael Vick's life feels like a cover for rehashing old and tired theories about single mothers, culture of poverty, and hip-hop/urbanness as the root of many problems. Of course race matters for not only Michael Vick but also everyone else residing in America. This is America, arguments about post-racialness notwithstanding.

Race mattered during the coverage of dogfighting and continues to matter for Vick in this very moment. It also matters given history. As Melissa Harris-Perry notes, race matters in relationship to Michael Vick (and the support he has received from the African American community) in part because of the larger history of white supremacist use of dogs against African Americans.

I sensed that same outrage in the responses of many black people who heard Tucker Carlson call for Vick's execution as punishment for his crimes. It was a contrast made more raw by the recent decision to give relatively light sentences to the men responsible for the death of Oscar Grant . Despite agreeing that Vick's acts were horrendous, somehow the Carlson's moral outrage seemed misplaced. It also seemed profoundly racialized. For example, Carlson did not call for the execution of BP executives despite their culpability in the devastation of Gulf wildlife. He did not denounce the Supreme Court for their decision in US v. Stevens (April 2010) which overturned a portion of the 1999 Act Punishing Depictions of Animal Cruelty. After all with this "crush" decision the Court seems to have validated a marketplace for exactly the kinds of crimes Vick was convicted of committing. For many observers, the decision to demonize Vick seems motivated by something more pernicious than concern for animal welfare. It seems to be about race.

Just as when Tucker Carlson said Vick should have been executed, or when commentators refer to him as thug, race matters; it matters in the demonization he experienced over the last 4 years. It is evident in the debates that took place following his release from prison, especially given the lifetime punishment experienced by many African Americans (see Michelle Alexander) or the very different paths toward forgiveness available to Vick (and countless other black athletes) compared to their white counterparts.

Race and racism have impacted his life in a myriad of ways. The continue significance of race matters in the ways in which this article plays upon and perpetuates cultural arguments that seemingly erase race, replacing it with flattened discussions of culture. The power of white privilege and the impacts of racism, segregation, and inequality are well documented, leaving me to wonder if the point of Touré's piece is not that race matters but rather that culture matters. And this is where we agree because culture is important here; a CULTURE of white supremacy does matter when thinking about Michael Vick or anything else for that matter.

--

Special thanks to Guthrie Ramsey, James Peterson, and Oliver Wang who all, in different ways, encouraged me to write a response.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on August 26, 2011 07:13

August 25, 2011

The Corporate King Memorial and The Burial of a Movement

The Corporate King Memorial and The Burial of a Movement by Jared Ball | Black Agenda Report

Dr. King and the liberation movement he represents will again suffer a brutal blow this week when all are permanently entombed under the violent euphemism of "memorial." The dedication of this $120 million stone sculpture is to be a national tribute to a man whose entire body of work was designed to destroy the very structure that now claims to honor him. It is no honor. It is a burial. The very entities against which the movement that produced King have struggled for centuries have now attached themselves to him as if to claim victory over, rather than along with, that man and that movement. This memorial should be seen as the hostile, disingenuous aggression against Dr. King that it is and should continue to be a reminder of the absolute absence of sincere change in this society.

Deborah Atwater and Sandra Herndon have written about the meaning of memorials and museums saying, in part, that they serve the "nation-state" by communicating an "official culture" whose job, "through sponsorship," is to "retain loyalty" and the "virtue of unity." Atwater and Herndon describe memorials as helping the state develop a " collective American public memory" and a "shared sense of the past." Museums and memorials become "the spaces in which that [public] memory is interpreted." Perhaps most importantly is that memorials are said to also "give meaning to the present." But given the vicious re-imaging King suffered before his assassination, the vitriol he withstood from a nation determined to resist the change he represented, and given the post-assassination routine destruction of his advancing radical politics, it is simply not hard to determine just what this memorial intends to convey or the present meaning it intends to define.

Listen Here

Published on August 25, 2011 17:52

August 24, 2011

Real Men?: Sports, Slavery, and Sex Trafficking

Real Men?: Sports, Slavery, and Sex Trafficking by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

In the midst of the NFL lockout, Adrian Peterson joined a chorus of players who were both critical of the league's owners and commissioner Roger Goodell, describing professional football as akin to "modern-day slavery":

People kind of laugh at that, but there are people working at regular jobs who get treated the same way, too. With all the money … the owners are trying to get a different percentage, and bring in more money. I understand that; these are business-minded people. Of course this is what they are going to want to do. I understand that; it's how they got to where they are now. But as players, we have to stand our ground and say, 'Hey — without us, there's no football.' There are so many different perspectives from different players, and obviously we're not all on the same page — I don't know. I don't really see this going to where we'll be without football for a long time; there's too much money lost for the owners. Eventually, I feel that we'll get something done.

Although not the first person to use the slavery analogy, with William C. Rhoden, Larry Johnson, and Warren Sapp all offering this rhetorical comparison, his comments elicited widespread commendation and criticism. Dave Zirin notes that he was denounced as "ungrateful," "out of touch," "an idiot" and, in the darker recesses of the blogosphere, far worse." Like much of sports media, the controversy quickly reached a zenith with columnists and fans ultimately focusing on other issues, spectacles, and controversies, although never forgetting his insertion of race into the world of sports.

Recently, however, an ESPN columnist brought a spotlight back onto his comments, celebrating Peterson's determination to right his rhetorical wrongs. In "Adrian Peterson continues righting a wrong" Kevin Seifert cites not only Peterson's efforts to apologize for his "unfortunate analogy," but his decision to get involved with anti-slavery efforts as part of a larger effort to make amends. "If some good came of Adrian Peterson's unfortunate use of analogies this offseason, it's this: It forced one of the NFL's highest-profile players into a bond with two of the world's most prominent advocates for ending human trafficking."

Citing his involvement with Demi Moore and Ashton Kutcher's DNA Foundation, a group committed to "rais[ing] awareness about child sex slavery, chang[ing] the cultural stereotypes that facilitate this horrific problem, and rehabilitat[ing] innocent victims," Seifert argues that Peterson missed-used analogy reflected a lack of knowledge about human trafficking. "As a professional and respectful public figure," Peterson would never knowingly make such a silly and harmful comparison had he known about the realities of human trafficking and child sex slavery. At least that seems to be the argument emanating from this piece. "I've always believed that Peterson wasn't making any sort of political statement," writes Seifert, whose column about Peterson's comments brought up the real-life circumstances of modern-day slavery. "There was no reason to think he harbored some previously unexpressed level of insensitivity. Like many of us, he probably just didn't know that in 2010, 12.3 million people world-wide were in forced or bonded labor. To that end, Peterson jumped at the chance to work with Moore and Kutcher."

Seifert's celebration of Peterson's PSA is questionable given his efforts to cite this as evidence of his efforts to do penance along the path to redemption. At one level, it is unclear if the PSA was in actuality a response to the controversy surrounding the comments (the interview took place in March and the PSA filming taking place shortly thereafter in April). At another level, and more importantly, Peterson had nothing to apologize for, and therefore his involvement with an organization committed to thwarting modern-day slave sex trafficking has nothing to do with his past comments about the NFL.

The relative silence of the media regarding his PSA, especially in comparison to the ubiquitous level of criticism that he experienced for deploying "the S-word" (Zirin), demonstrates that irrespective of his actions it will be difficult for him to secure redemption in the eyes of mainstream America. Richard King and I wrote about the precarious path to redemption experienced by many black athletes in wake of controversies in "Lack of Black Opps: Kobe Bryant and the Difficult Path of Redemption" (Journal of Sport and Social Issues). There we argue,

The media and public fascinations with Kobe Bryant, Tiger Woods, and other Black athletes accused of personal and/or criminal transgressions should remind us of what a prominent place race, redemption, and respectability play in sport today. Sport media not only rely on the White racial frame but also play a leading role in its reproduction. In this frame, Blackness has overdetermined the actions of African American athletes from O. J. Simpson, Mick Tyson, and Barry Bonds to Ron Artest, Shani Davis, and more recently Marion Jones, Michael Vick, Santonio Holmes and Tiger Woods, creating a context in which interpretations and outcomes for Black and White athletes vary greatly. . . . Yet what is clear is in spite of the celebration of the comeback stories of Tiger Woods, Kobe Bryant, or even Michael Vick, their Blackness, and the broader significations associated with their Black bodies contains and limits their public rehabilitation. Just as their Blackness continues to confine the meaning of their bodies inside and outside of the sports world, their past "mistakes" and "misfortunes" (as Black men) cannot be outrun, out maneuvered, and even controlled.

In other words, while recognizing the unfairness in demanding redemption from Peterson for comments about exploitation and abuse through a deployed slavery analogy, he faces a difficult challenge given the ways in which race and the associated tropes of the "ungrateful," and "militant" black athlete governs over Peterson in wake of these comments. Yet, the specific nature of the PSA itself lends itself toward some sort of redemption.

Peterson appears in a PSA as part of DNA's "Real Men" campaign, which includes spots from Bradley Cooper ("Real men know to make a meal"), Sean Penn ("Real Men know how to use an Iron") and Jamie Foxx ("Real Men know how to use the remote.") In his PSA, Peterson is sitting in a living room befitting of a member of the aristocracy (or at least the American upper-class). Confirming his class status and respectability, Peterson simultaneously represents an authentic manhood, able to start a fire by merely rubbing his hands together. Unlike other men, Peterson embodies a true and enviable manhood, evident in his physical prowess and his economic prowess. In this regard, his blackness is muted by a desired class- and gender-based identity.

Peterson's represented identity is an important backdrop for both his purported redemption resulting from his participation in this campaign and the PSA itself. The narrative argument offered within the campaign is that "real men don't buy girls," and that "real men" don't participate in "child sex slavery." Peterson, as a man who can start a fire with his bare hands, and who is economically successful (not to mention someone who make defenders look silly) is already a real man within a hegemonic frame; his stance against sex slavery is but another signifier of a real masculinity, all of which is constructed as important attracting women. The PSA ends with a young woman asking, "Are you a real man," followed by a clear reminder: "I prefer a real man." At this level, the PSA is disturbing in that it tells viewers to oppose childhood sex slavery because that is what real men do and because women of age find such a stance attractive.

In a world where 12 million people are enslaved and where 2 million children are bought into the global sex trade, it is rather simplistic (and comforting) to reduce this injustice to a faulty masculinity. Given that sex trafficking, according to the United Nations, involves "127 countries of origin, 98 transit countries and 137 destination countries" it is rather dubious to reduce the problem to a single construction of bad masculinity.

And to be clear, this isn't just ELSEWHERE, with between 100,000 and 300,000 girls sold into sex slavery yearly, with many more "at risk of being sexually exploited for commercial uses." Whether in the U.S. or elsewhere, the existence of child human sex trafficking reflects patriarchy and the dehumanizing ideologies that govern society.

Catherine MacKinnon makes this clear in her analysis of global sex trafficking:

If women were human, would we be a cash crop shipped from Thailand in containers into New York's brothels? Would we be sexual and reproductive slaves? Would we be bred, worked without pay our whole lives, burned when our dowry money wasn't enough or when men tired of us, starved as widows when our husbands died (if we survived his funeral pyre)?

She notes further the links between sexual violence, heterosexism, and dominant notions of masculinity

Male dominance is sexual. Meaning: men in particular, if not men alone, sexualize hierarchy… Recent feminist work… on rape, battery, sexual harassment, sexual abuse of children, prostitution, and pornography supports [this]. These practices, taken together, express and actualize the distinctive power of men over women in society; their effective permissibility confirms and extends it." (In Dunlap)

The links between sex trafficking and patriarchy and misogyny, along with racism, xenophobia, and global geo-politics is further illustrated by comments offered during a NGO forum, which among other things dispels arguments about "bad apples," individual pathologies, and "real/unreal" men:

Trafficking in persons is a form of racism that is recognized as a contemporary form of slavery and is aggravated by the increase in racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance. The demand side in trafficking is created by a globalized market, and a patriarchal notion of sexuality. Trafficking happens within and across borders, largely in conjunction with prostitution (In Agathangelous and Ling ).

In other words, "real manhood," as codified legally, as defined culturally, and as constructed ideologically not only sanctions sexual violence but also promotes its very existence. Child sex trafficking reflects the logic of hegemonic masculinity. While comforting to imagine the problem of child sex trafficking as an aberrant and abhorrent masculinity, this injustice has nothing to do with real or a desirable manhood. It is about power, hierarchies, and the systemic dehumanization of women, particularly women of color.

The problem of slavery is real and reflects the systemic and historic manifestations of sexism (along with racism and colonization). To imagine this as a problem of a faulty masculinity does not work to eradicate the problem. While I certainly applaud the efforts of DNA, and celebrated Peterson's involvement with a campaign committed to raising awareness about the painful realities of human trafficking, the narrative leads us back to the same place.

Taking a stand against child sex trafficking and other forms of sexual violence reflects a willingness to embrace a feminist ethos, not one of "a real man." The struggle against sexual violence, whether it be rape or sex trafficking, should not be about redeeming and celebrating REAL men, Adrian Peterson, Justin Timberlake (who shaves with a chain saw), or anyone else, but challenging the injustices that result from hegemonic patriarchy. How about we make a PSA about real resistance and real transformation rather than real men!

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

Published on August 24, 2011 18:01

Where Does Race Fit in TV's New 1960s Stake?

Where Does Race Fit in TV's New 1960s Stake? by Geneva S. Thomas | HuffPost BlackVoices

The success of AMC's Mad Men signals new interest in the 1960s for American television. This fall, both ABC and NBC will roll out series focusing on two iconic American institutions during the seething decade. ABC's Pan Am promises a stylish series centered on luxury travel and the historic international airline -- where "pilots were rock stars and the stewardesses are the most desirable women." Keeping with this sexy theme, NBC's The PlayBoy Club will take viewers behind the legendary Chicago club's bunny ears. Somewhat of a spin-off -- the show reprises Naturi Naughton's cameo on Mad Men as one of the nightclub's only African-American bunnies.

But with TV's new interest in the 1960s, and Naughton as the lone player of color -- exactly where does race fit, it at all?

The nostalgic '60s have proven to be a winning point of interest for TV. Not only does the time capsule secure viewers out of sentimental 40-somethings -- a cash-cow market for advertisers according to Ad Age -- but like Mad Men these shows are likely to attract the curiosities of America's youth who are in search of vintage pop culture -- lifestyle and trending swag included. If Mad Men is any indication, we can expect Pan Am and The Playboy Club's treatment of race to be sedated and barely there.

The nostalgic '60s have proven to be a winning point of interest for TV. Not only does the time capsule secure viewers out of sentimental 40-somethings -- a cash-cow market for advertisers according to Ad Age -- but like Mad Men these shows are likely to attract the curiosities of America's youth who are in search of vintage pop culture -- lifestyle and trending swag included. If Mad Men is any indication, we can expect Pan Am and The Playboy Club's treatment of race to be sedated and barely there. Critics slammed Mad Men -- the award-winning series set smack in the middle of 1960s New York -- for its sluggish narrative on the civil rights movement. While Mad Men offered dead-on confrontation of other prominent unfortunate '60s fixtures, like then legal cooperate sexual harassment, and drug culture, the show's eventual submission to race was swelled with subtle and allegorical representations -- mainly the Draper's muted black nanny and the Sterling Cooper building's perquisite black male elevator operator, the former earning her own satirical Twitter handle. But it was Naughton's cameo in the show's fourth season as a black Playboy bunny that brought race from under a Madison Avenue office desk to center stage when she won the heart of the agency's British partner Lane Pryce -- a man married with children. True to '60s form, when Lane's father caught wind of the affair, the elderly Londoner chastised Lane with a cane across the face.

New '60s-themed TV on the cuffs of controversy around number one box-office hit The Help should serve as a racial-GPS on what not to do. Historical inaccuracies and age-old Hollywood white-washing proves a combination clearly worthy of Oscar buzz, and lingering community outrage to tote. In this case, I'm certain black viewers would rather these shows go entirely absent of faux recollections of civil rights America. But does there exist a safe and sturdy middle ground for TV's approach to the precarious text on race? Or should we all lie in the post-primetime beds TV's '60s do-over will inevitably make -- the imagined space where blackness has no real true place at all?

***

Geneva S. Thomas is a writer and cultural critic.

Published on August 24, 2011 17:28

August 22, 2011

Black Sambo 2.0? New Media Technology and the Persistence of Racist Representations

Black Sambo 2.0? New Media Technology and the Persistence of Racist Representations by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

New media technology is changing the landscape of television. At one level, the emergence of web-based television, along with platforms like YouTube, provides a space for historically ignored themes and silenced voices within popular culture. I previously wrote about the potential during a discussion of The LeBrons, which "highlights how new media technologies provide modern black athletes (among others) tools to define their own image and message, partially apart from those 'restrictive script,' yet bound by the dominant discourse and accepted images."

Reflecting on this cultural and technological shift, Aymar Christen Jean argues that the golden age of black television has ended. He notes further that the potential afforded by new media technologies are significant in challenging the white hegemony of American television culture: "In this early stage, the writing and production values are uneven. But when you throw in social-networking possibilities online, the emergence of original Web programming can only be good news for black art and expression." Writing about the brilliant and rightly celebrated The Misadventures of AWKWARD Black Girl, Britni Danielle highlights the transformative potential residing in Web 2.0. "It's official, the best shows featuring Black people are not on BET, TVOne, NBC, or any other TV channel. The best shows featuring interesting Black characters are on the web," writes Danielle. "In times like these, when TV shows and films featuring interesting Black characters are missing from most mainstream outlets, it's nice to see that many (and I do mean many) are taking matters into their own hands and making their own way."

While clear, from The Misadventures of AWKWARD Black Girl, The New 20s, The LeBrons, Kindred, and Road to the Alter, that the web is emerging as the promise land for the production of black-themed shows and the dissemination of counter-narratives and representations, the frontier of new media technology is also littered with dehumanizing shows as well.

The advance of new media technology, whether on YouTube, I-Tunes, or the totality of the Internet provides a space for the dissemination of racist shows of yesterday, narratives, stereotypes, and episodes that artists fought long and hard to remove from public consumption. William Van De Burg, in New Day in Babylon, documents the ways in which organizations, like the National Black Media Coalition and Black Citizens for Fair Media, fought the continued dissemination of racist imagery. They, along with Asian Americans for Fair Media and others, worked hard to counter those racial images that represented "an explosive psychological force that warps human relationships and wreaks havoc on one's personal dignity" (Wei, 1993; 51). While movements of the 1960s and 1970s were successful in challenging the presence of dehumanizing representations within network television, the advance of new media has proven to given life to many shows of past generations.

On YouTube, you can find a number of cartoons from the mid-20th century, some of which are explicitly labeled as racist (or banned/censored) cartoons, while others lack specific marking. These cartoons bring into wide circulation the otherwise put into the grave racist televisual moments of yesteryear. For example, on YouTube, "Southern Fried Rabbit" where bugs sings, "I wish I was in Dixie," also depicts the South as a beautiful oasis in juxtaposition to the barren wasteland of the North. In this episode, Bugs Bunny is presented in blackface, ultimately impersonating a happy slave. At one level, this particular episode is keeping "past" images and narratives alive (the happy slave is clear in circulation as evidence by "pledge"); at another level, it facilitates a space where commentators can rehash and deploy their own racial narratives and ideologies. Claims about permissibility of racist images back then, that it was just entertainment, and simply kid's stuff are commonplace on YouTube. Likewise, in this episode and in countless others found on YouTube, the history of blackface, of imagining and depicting blackness through dehumanizing imagery is evident.

Bugs Bunny is not the only example with terribly racist episodes of The Flintstones, Tom and Jerry, and Popeye, some of which you can find on not only YouTube but iTunes as well. For example, "Frigid Hare," a Bugs Bunny episode that portrays Eskimos as bucktooth savages is available for purchase today. Tom and Jerry is also available on iTunes, including "His Mouse Friday" where in an effort to defeat Tom, Jerry dons blackface only to see the "real savages" of the Island handle his nemesis. Likewise, a number of Popeye episodes, including "You're A Sap, Mr. Jap," "Scrap the Japs," "I Yam what I Yam," "Popeye the Sailor" all which deploy dehumanizing stereotypes of Japanese, Native Americans and African Americans, representing them as the enemy, as savages, as foils to the heroism/ righteousness of Popeye, and ultimately as the Other. Having recently purchased Popeye, unaware to the racist content several shows, I was horrified at the sight of my children watching a show that portrayed Native Americans as racist savages who threatened the civilization, goodness, and whiteness embodied by Popeye.

The preservation of these shows via YouTube and iTunes demonstrates how new media is making available the very harmful and violent representations of yesteryear to future generations. While defenders like to talk about these cartoons being sixty years old and that blackface, representations of Native Americans, African Americans, Chinese, and Japanese as savages, and countless other racist tropes were all acceptable back then, the persistent availability of these shows illustrates how indeed these images and ideologies remain alive and well in the twenty-first century. The continued availability of these shows counters those who dismiss Popeye, Bugs Bunny, and Tom and Jerry as a product of their times, and therefore insignificant today, given the continued consumption of these racist stereotypes. Sure, these shows tell us something about the ideologies of race in the 1930s and 1940s during production, but also the ways in which race operates in 2011, the moment of consumption.

To me, the willingness and desire to watch shows that dehumanize is telling. It is disheartening as generations forward will continue to consume those overtly racist caricatures of people of color all while consuming the often more subtle, yet equally harmful, representations of our current moment, perpetuating white racial frames and stereotypes. So next time the kids are searching for something to watch on YouTube or buy a cartoon from iTunes be aware because racist images are just one click away.

***

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He has written on sport, video games, film, and social movements, appearing in both popular and academic mediums. His work explores the political economy of popular culture, examining the interplay between racism, state violence, and popular representations through contextual, textual, and subtextual analysis. He is the author of Screens Fade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop (SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris.

[image error]

Published on August 22, 2011 09:57

August 21, 2011

Cathy Davidson: Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Learn

In her new book Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Learn , Duke University Professor Cathy N. Davidson explores how the advent of the Internet is changing what we see.[image error]

Published on August 21, 2011 17:59

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.