Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1040

December 9, 2011

Lawrence P. Jackson to Receive MLA Award for Outstanding Scholarly Study of Black American Literature

from the

Modern Language Association (MLA)

from the

Modern Language Association (MLA)

LAWRENCEP. JACKSON TO RECEIVE THE MLA'S WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH PRIZE FOR ANOUTSTANDING SCHOLARLY STUDY OF BLACK AMERICAN LITERATURE OR CULTURE

NewYork, NY – 5 December 2011 – The Modern Language Association of America todayannounced it is awarding its tenth annual William Sanders Scarborough Prize toLawrence P. Jackson, professor of English and African American studies at EmoryUniversity, for his book The Indignant Generation: A Narrative History ofAfrican American Writers and Critics, 1934– 1960, published by PrincetonUniversity Press. The prize is awarded for an outstanding scholarly study ofblack American literature or culture.

TheWilliam Sanders Scarborough Prize is one of eighteen awards that will bepresented on 7 January 2012, during the association's annual convention, to beheld in Seattle. The members of the selection committee were James J. Davis(Howard Univ.), chair; Thadious Davis (Univ. of Pennsylvania); and RobertLevine (Univ. of Maryland). The committee's citation for the winning bookreads:

Inthis magisterial narrative history of African American literature running fromthe end of the Harlem Renaissance to the beginning of the civil rights period,Lawrence P. Jackson expands the archive for assessing African American writingduring a period that has often been reduced to protest writing. Jackson placeswriters into fresh contexts of cohorts (critics and editors included) andthreads a clear narrative line through three heady decades jam-packed withAfrican American authors publishing in a variety of genres and venues. Jacksonis excellent on the important influence of the Communist Party, onmid-twentieth-century black literary culture, and on issues of publishing andreception. Beautifully written and rich in historical detail, The IndignantGeneration should quickly become a standard work in twentieth-centuryAfrican American studies and United States publishing history.

LawrenceP. Jackson is a professor of English and African American studies at EmoryUniversity. He is the author of Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius, 1913–1952and the forthcoming My Father's Name: A Black Virginia Family after theCivil War. His criticism and nonfiction have appeared in publications suchas Baltimore Magazine, New England Quarterly, Massachusetts Review, AntiochReview, American Literature, and American Literary History. Theholder of a doctorate degree in English and American literature from StanfordUniversity, Professor Jackson has held fellowships from the W. E. B. Du BoisInstitute at Harvard University, the Stanford Humanities Center, the FordFoundation, and the National Humanities Center. He began his teaching career atHoward University in 1997. His current project is a biography of Chester Himes.

TheModern Language Association of America and its 30,000 members in 100 countrieswork to strengthen the study and teaching of languages and literature. Foundedin 1883, the MLA provides opportunities for its members to share theirscholarly findings and teaching experiences with colleagues and to discusstrends in the academy. The MLA sustains one of the finest publication programsin the humanities, producing a variety of publications for language andliterature professionals and for the general public. The association publishesthe MLA International Bibliography, the only comprehensive bibliographyin language and literature, available online. The MLA Annual Conventionfeatures meetings on a wide variety of subjects; this year's convention inSeattle is expected to draw 8,000 attendees. More information on MLA programsis available at www.mla.org.

TheWilliam Sanders Scarborough Prize was established in 2001 and named for thefirst African American member of the MLA. It is awarded under the auspices ofthe Committee on Honors and Awards. The prize has been awarded to Eddie S.Glaude, Jr., Maurice O. Wallace, Joanna Brooks, Jean Fagan Yellin, Alexander G.Weheliye, Jacqueline Goldsby, Candice M. Jenkins, Magdalena J. Zaborowska, andMonica L. Miller. Honorable mentions have been given to Thadious M. Davis,Susan Gillman, and Daphne Lamothe.

Otherawards sponsored by the committee are the William Riley Parker Prize; the JamesRussell Lowell Prize; the MLA Prize for a First Book; the Howard R. Marraro Prize;the Kenneth W. Mildenberger Prize; the Mina P. Shaughnessy Prize; the MLA Prizefor Independent Scholars; the Katherine Singer Kovacs Prize; the Morton N.Cohen Award; the MLA Prizes for a Distinguished Scholarly Edition and for aDistinguished Bibliography; the Lois Roth Award; the Fenia and Yaakov LeviantMemorial Prize in Yiddish Studies; the MLA Prize in United States Latina andLatino and Chicana and Chicano Literary and Cultural Studies; the Aldo andJeanne Scaglione Prizes for Comparative Literary Studies, for French andFrancophone Studies, for Italian Studies, for Studies in Germanic Languages andLiteratures, for Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures, for a Translationof a Literary Work, for a Translation of a Scholarly Study of Literature; andthe Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Publication Award for a Manuscript in ItalianLiterary Studies.

William Sanders Scarborough(1852–1926) was the first African American member of the Modern LanguageAssociation. Brought up in the South, Scarborough was a dedicated student oflanguages and literature. He attended Atlanta University and graduated in 1875from Oberlin College, where he later received an MA degree. After teaching atvarious Southern schools, Scarborough was appointed professor of Latin andGreek at Wilberforce University. He later served as president of the universityfrom 1908 through 1920. Scarborough's published works include First Lessonsin Greek (1881) and Birds of Aristophanes (1886) and many articlesin national magazines, including Forum and Arena. In 1882 he wasthe third black man to be elected for membership in the American PhilologicalAssociation. Scarborough's areas of interest included classical philology andlinguistics with an emphasis on Negro dialects.

Published on December 09, 2011 14:16

Lawrence P Jackson to Receive MLA Award for Outstanding Scholarly Study of Black American Literature

from the

Modern Language Association (MLA)

from the

Modern Language Association (MLA)

LAWRENCEP. JACKSON TO RECEIVE THE MLA'S WILLIAM SANDERS SCARBOROUGH PRIZE FOR ANOUTSTANDING SCHOLARLY STUDY OF BLACK AMERICAN LITERATURE OR CULTURE

NewYork, NY – 5 December 2011 – The Modern Language Association of America todayannounced it is awarding its tenth annual William Sanders Scarborough Prize toLawrence P. Jackson, professor of English and African American studies at EmoryUniversity, for his book The Indignant Generation: A Narrative History ofAfrican American Writers and Critics, 1934– 1960, published by PrincetonUniversity Press. The prize is awarded for an outstanding scholarly study ofblack American literature or culture.

TheWilliam Sanders Scarborough Prize is one of eighteen awards that will bepresented on 7 January 2012, during the association's annual convention, to beheld in Seattle. The members of the selection committee were James J. Davis(Howard Univ.), chair; Thadious Davis (Univ. of Pennsylvania); and RobertLevine (Univ. of Maryland). The committee's citation for the winning bookreads:

Inthis magisterial narrative history of African American literature running fromthe end of the Harlem Renaissance to the beginning of the civil rights period,Lawrence P. Jackson expands the archive for assessing African American writingduring a period that has often been reduced to protest writing. Jackson placeswriters into fresh contexts of cohorts (critics and editors included) andthreads a clear narrative line through three heady decades jam-packed withAfrican American authors publishing in a variety of genres and venues. Jacksonis excellent on the important influence of the Communist Party, onmid-twentieth-century black literary culture, and on issues of publishing andreception. Beautifully written and rich in historical detail, The IndignantGeneration should quickly become a standard work in twentieth-centuryAfrican American studies and United States publishing history.

LawrenceP. Jackson is a professor of English and African American studies at EmoryUniversity. He is the author of Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius, 1913–1952and the forthcoming My Father's Name: A Black Virginia Family after theCivil War. His criticism and nonfiction have appeared in publications suchas Baltimore Magazine, New England Quarterly, Massachusetts Review, AntiochReview, American Literature, and American Literary History. Theholder of a doctorate degree in English and American literature from StanfordUniversity, Professor Jackson has held fellowships from the W. E. B. Du BoisInstitute at Harvard University, the Stanford Humanities Center, the FordFoundation, and the National Humanities Center. He began his teaching career atHoward University in 1997. His current project is a biography of Chester Himes.

TheModern Language Association of America and its 30,000 members in 100 countrieswork to strengthen the study and teaching of languages and literature. Foundedin 1883, the MLA provides opportunities for its members to share theirscholarly findings and teaching experiences with colleagues and to discusstrends in the academy. The MLA sustains one of the finest publication programsin the humanities, producing a variety of publications for language andliterature professionals and for the general public. The association publishesthe MLA International Bibliography, the only comprehensive bibliographyin language and literature, available online. The MLA Annual Conventionfeatures meetings on a wide variety of subjects; this year's convention inSeattle is expected to draw 8,000 attendees. More information on MLA programsis available at www.mla.org.

TheWilliam Sanders Scarborough Prize was established in 2001 and named for thefirst African American member of the MLA. It is awarded under the auspices ofthe Committee on Honors and Awards. The prize has been awarded to Eddie S.Glaude, Jr., Maurice O. Wallace, Joanna Brooks, Jean Fagan Yellin, Alexander G.Weheliye, Jacqueline Goldsby, Candice M. Jenkins, Magdalena J. Zaborowska, andMonica L. Miller. Honorable mentions have been given to Thadious M. Davis,Susan Gillman, and Daphne Lamothe.

Otherawards sponsored by the committee are the William Riley Parker Prize; the JamesRussell Lowell Prize; the MLA Prize for a First Book; the Howard R. Marraro Prize;the Kenneth W. Mildenberger Prize; the Mina P. Shaughnessy Prize; the MLA Prizefor Independent Scholars; the Katherine Singer Kovacs Prize; the Morton N.Cohen Award; the MLA Prizes for a Distinguished Scholarly Edition and for aDistinguished Bibliography; the Lois Roth Award; the Fenia and Yaakov LeviantMemorial Prize in Yiddish Studies; the MLA Prize in United States Latina andLatino and Chicana and Chicano Literary and Cultural Studies; the Aldo andJeanne Scaglione Prizes for Comparative Literary Studies, for French andFrancophone Studies, for Italian Studies, for Studies in Germanic Languages andLiteratures, for Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures, for a Translationof a Literary Work, for a Translation of a Scholarly Study of Literature; andthe Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Publication Award for a Manuscript in ItalianLiterary Studies.

William Sanders Scarborough(1852–1926) was the first African American member of the Modern LanguageAssociation. Brought up in the South, Scarborough was a dedicated student oflanguages and literature. He attended Atlanta University and graduated in 1875from Oberlin College, where he later received an MA degree. After teaching atvarious Southern schools, Scarborough was appointed professor of Latin andGreek at Wilberforce University. He later served as president of the universityfrom 1908 through 1920. Scarborough's published works include First Lessonsin Greek (1881) and Birds of Aristophanes (1886) and many articlesin national magazines, including Forum and Arena. In 1882 he wasthe third black man to be elected for membership in the American PhilologicalAssociation. Scarborough's areas of interest included classical philology andlinguistics with an emphasis on Negro dialects.

Published on December 09, 2011 14:16

December 8, 2011

Ice Cube Celebrates the Eames | Pacific Standard Time

From Pacific Standard Time:

Ice Cube drives Inglewood blvd. describing the Los Angeles that he knows. He talks of landmarks like The Forum, Five Torches, Cockatoo Inn, Brolly Hut, and Watts Towers. He refers to the 110 as "Gangsta Highway". Cube says coming from South Central LA teaches you how to be resourceful. The video cuts to Cube walking the Eames House perimeter, through the Eames living room, and sitting in the Eames lounge chair.

He brings us back to his NWA years when he studied architectural drafting before launching his rap career. One thing he learned that translates is to always have a plan. Cube describes the modern, green and resourceful building design of Charles and Ray Eames. Visionaries of connecting nature and structure. Cube ends by saying "Who are these people who got a problem with LA? Maybe they mad cuz they don't live here."

Published on December 08, 2011 11:56

The Class Room & the Cell: Marc Lamont Hill Discusses His New Book with Jasiri X

Jasiri X Interviews Marc Lamont Hill about the new book that he wrote with Mumia Abu-Jamal, The Classroom And The Cell (Third World Press) -

Directed By Paradise Gray For 1Hood Media. (Filmed at the The University Of Pittsburgh's "Evolving the Image Summit")

Published on December 08, 2011 10:59

December 7, 2011

Rebirth of a Nation: Race and Gender Politics In Today's Media

Last month, the Black Youth Project hosted a dynamic and fascinating panel discussion, Rebirth of a Nation: Race and Gender Politics In Today's Media:

Featuring Bakari Kitwana, Vijay Prashad, Rosa Clemente, Mark Anthony Neal, Joan Morgan and Che "Rhymefest" Smith), the conversation was inspiring, enlightening and robust, tackling such controversial topics as the Obama Presidency, The Occupy Movement, gender politics, our insidious 24-hour news cycle, and Hip Hop as a tool for social change.

Rebirth of a Nation was sponsored by The Center for the Study of Race, Politics and Culture, the Organization of Black Students at the University of Chicago, The Black Youth Project, and Rap Sessions: Community Dialogues on Hip Hop.

Published on December 07, 2011 20:08

Business as Usual: Big Time College Sport and Inequality

Businessas Usual: Big Time College Sport and Inequality byRichard C. King and David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

On December 6, 2011, amid the jubilation of students and alumni,fanfare from the marching band, and media hype, Washington State University(WSU) presented its new football coach to the public. After four losingseasons, the announcement of that a proven winner would take the helm hadCougar nation in a frenzy, excited by the high scoring offense and return offun to the Palouse. Much of the media coverage echoed fan sentiment: Withheadlines like "Why Mike Leach is Awesome" and "Leach is a Dream hire," journalists andpundits alike celebrated the bold decision making of Athletic Director BillMoos and the promising future of the once great program.

Apparently, the unfolding sex abuse scandals at Penn State andSyracuse, the play of Ndamukong Suh, and the NBA labor agreement have exhaustedthe always-limited critical powers of the sport media and sport fans alike.Even in a social moment seemingly primed for connections between sport andsociety, few, if any public voices seemed willing or able to do so: the shortlived outrage sparked by Taylor Branch's "The Shame of the Game" a scant two monthearlier had no lasting resonance, no place in public discourse. In fact, whenframed critically for students on campus, our classes reacted withindifference, if not hostility.

Two fundamental issues are lost in the hype, pleasure, andpossibilities surrounding the new hire: the racial politics of collegeathletics and the increasingly inadequate resources devoted to highereducation. Indeed, the hiring of Jim Leach exposes the workings of highereducation in stark terms, highlighting the ways in which the status quosimultaneously perpetuates economic and racial inequality and masks structuresof power. Fifty years after integration of it began in earnest, big timecollege athletics remains one of the clearest of examples of racial inequityand racist exclusion in the United States. Historically white collegesand universities exploit black bodies for publicity and profit. Althoughblack athletes have dominated football for decades, few coaches and feweradministrators are African American. Efforts by organizations like BlackCoaches and Administrators have made a difference to be sure: African Americanhead coaches have rise from 1 in 1979 to 25 at the start of this season andtoday 31 of 260 offensive and defensive coordinators (11.9%) are black. The recent firing of Turner Gill at the University of Kansas not onlyreduces the total number of active head coaches, but reminds us how limited thesuccess of black coaches is: only one black coach (Tyrone Willingham) has beenhired after being fired as a head coach (see here for additional information). Thehiring of Mike Leach thus fits a broader pattern. Historically whiteuniversities headed by white Athletic Directors, such as Bill Moos at WSU, tendto hire white coaches.

Arguably more troubling is how Leach was hired. The searchcommittee appears to have been Moos, who wanted to make a bold statement aboutCougar athletics, increase attendance and alumni interest, and make the programrelevant again. This too resonates with prevailing practices in collegeathletics, ranging from unilateral hires to selecting internal hires groomedfor the position, and virtually ensures the unbearable whiteness of collegecoaching, where the failure to take measures to cultivate and promote a diverseathletic leadership, it is unlikely it will ever materialize. This hasnothing to with overt racism and isn't a question about the intentions of anyindividual. Rather priorities andpreoccupations render such questions largely unthinkable, and when asked theyare deflected by defensiveness about "how race doesn't matter" and how he was"best qualified person." In the end, don't we need to reflect on why, how andthe significance of candidate pool being overwhelmingly white?

Inits most recent Annual Hiring Report Card, the BCA gave WSU a C for its hiringpractices. No doubt, the fait d'accompli hiring of Leach would receive an F.But one might wonder when did grades ever stop fans and alumni from enjoyingcollege football. As with the larger shifts in our society that hasresulted in further economic inequality, even more evident as we examinepersistent and worsening racial inequality, we are struck by the symbolism hereof the a millionaire white coach profiting off the labor of black players evenwhile the students, faculty and staff at the university are left behind bytuition increases, worsening working conditions, and a culture defined bybudget cuts.

Aswith much of the 1%, Leach's salary far exceeds that the 99% of faculty andstaff at Washington State University. Earning an astounding 2.25 milliondollars per year, Leach is set to become the third highest coach in thePac-12. Compared to the average associate faculty members' salary,who makes $74,700, the disparity in income is significant. The gulfbetween faculty and college football coaches is a relatively newphenomenon. For example, in 1969, the head coach at Oregon StateUniversity earned $24,000, while the school's president earned $34,500 and thedean of the college education brought home $29,760. As of 1986, salarieshad not increased significantly, with the average NCAA football coach earningroughly 150,000. Beginning in the 1990s, this changed with the normslowly becoming over 1 million dollars. Obviously faculty salaries havenot increased on similar levels. The income gulf evident between footballcoaches and faculty is emblematic of larger inequality that defines thatrelationship between the 1% and the 99%. In "Of the 1%, by the 1%, forthe 1%," Joseph E. Stiglitz reflects on this historicalshift

It's no use pretending that what has obviously happenedhas not in fact happened. The upper 1 percent of Americans are now taking innearly a quarter of the nation's income every year. In terms of wealth ratherthan income, the top 1 percent control 40 percent. Their lot in life hasimproved considerably. Twenty-five years ago, the corresponding figures were 12percent and 33 percent.

Thesame shift and income inequality that is evident in society at large is visiblewith the income gap between college football coaches and everyone else.

Accordingto the Sports Business Journal, the athletic budgetfor Washington State University increased from $37.0 million in 2010 to $38.5in 2011. For 2012, the budget was set at $39.3 million, representing a+6.2% increase. And this was all before the hiring of Mike Leach. If we can examine these numbers within a larger history, it is clear that adisproportionate amount of revenues and much of costs are associated with thefootball program. Michael Oriard, in Bowled over: Big-Time CollegeFootball from the Sixties to the BCS Era, Washington State football generatedalmost 10.5 million in revenue (as part of 38.2 million in total revenues forall of athletics), yet it spent 7.5 million (the athletic department spent 38.2million). And that was before Mike Leach.

Onthe heels of endless chatter about overpaid NBA players being tone deaf to theeconomic difficulties facing the NBA and the nation at large, the absence of aconversation about the salaries of college football coaches is particularlyrevealing. On the heels of widespread demonization of teachers and otherpublic employees as overpaid and pampered, the absence of a sustaineddiscussion of investment of public colleges and universities for footballcoaches is telling. Like state investment in prisons (in California, the5 highest paid state employees work in prisons), the investment in collegiatesports is a testament to our collective priorities. The expenditures and thesilence from the citizenry, media, and institutions illustrates the values of asociety, one that puts profits over people, that puts victories over education,and one that puts the potential of a successful football program ahead ofanything else.

Whilethe hiring of Mike Leach focuses our attention, to make this about Leach oreven WSU is to miss the point, misconstrue our analysis and misdirect ourenergies. The erasure of context, the dissolution of structure and powerwithin media spectacle, and the seeming impossibility of critique are systemicand systematic, just as with the case in the perpetuation of racial andeconomic inequality. In the end, this is not a commentary of Leach orother individuals but instead priorities and values, inequality anddivisions. It is as much about a media that flocks to campus for a pressconference while failing to give attention to the meaningful issues facing ofall us. It is about a campus that unreflectively celebrates what it allmeans for us, that rarely is encouraged to think about us beyond the sport teamand never asked to determine what it all means. It is a reminder that amid the99% at America's universities, football coaches are the 1%.

***

C. RichardKing is the Chair of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington StateUniversity at Pullman and the author/editor of several books, including Team Spirits: The Native American MascotControversy and Postcolonial America.

David J. Leonard is Associate Professor in the Department of CriticalCulture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington State University, Pullman. He isthe author of Screens Fade to Black:Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris. Follow him on Twitter @DR_DJL.

Published on December 07, 2011 19:09

Politics as Usual: Decoding the Attacks on a Liberal Education

Politics as Usual: Decoding the Attacks on a LiberalEducation by David J. Leonard, Mark Anthony Neal and JamesBraxton Peterson | NewBlackMan

Few university courses generate much attention frommainstream media, but Georgetown Professor Michael Eric Dyson's course "TheSociology of Hip-Hop: Urban Theodicy of Jay-Z" has drawn national attentionfrom NBC's Today Show, The Washington Post, The Associated Press, USA Today, and Forbes.com among many others. To be sure such attention is not unusual for Dyson, who is one of themost visible academics in the United States and has offered courses dealingwith hip-hop culture, sociology, and Black religious and vernacular expressionfor more than twenty-years. Yet,such attention seems odd; hundreds of university courses containing asignificant amount of content related to Hip-hop culture and Black youth aretaught every year—and have been so, for more than a decade. In addition, there are dozens ofscholarly studies of Hip-hop published each year—Julius Bailey's edited volume Jay-Z:Essays of Hip-Hop's Philosopher King , among those published just thisyear—and two Ivy League universities, Harvardand Cornell, boastscholarly archives devoted to the subject of Hip-Hop.

Any course focused on a figure like Jay-Z (Shawn CoreyCarter), given his contemporary Horatio Algernarrative, and his reputation as an urban tastemaker, was bound to generateconsiderable attention, but the nature of the attention that Dyson's class hasreceived and some of the attendant criticism, suggest that much more is atplay.

In early November, The Washington Post offered some of the first national coverage ofthe class, largely to coincide with the arrival of Jay-Z and Kanye West's Watch the Throne tour to Washington DC'sVerizon Center. Jay-Z dutifullycomplied with the attention by giving Professor Dyson a shout-out from thestage. The largely favorable article about the class, did make note, as have manysubsequent stories, about the cost of tuition at Georgetown; as if somehow thecost of that tuition is devalued by kids taking classes about hip-hop culture.

Other profiles of the course and Dyson have gone outof their way to make the point that the course had mid-term and final exams, asif that wouldn't be standard procedure for any nationally recognized seniorscholar at a top-tier research university in this country. Such narrative slippages speak volumesabout the widespread belief that courses that focus on some racial and culturalgroups, are created in slipshod fashion and lack rigor; it is a critique thatis well worn, and that various academic disciplines, such as Women's Studies,Ethnic Studies and even Sociology have long had to confront.

As ethnomusicologist Joe Schoss, author of Foundation:B-boys, B-girls and Hip-Hop Culture in New York , recently suggested onFacebook, courses constructed around the mythology of "great men" are often thevehicle in which outlier disciplines are made legible within traditionalacademic settings. Indeed Dyson's career has been marked by such studies, wherehe's examined figures such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Marvin Gaye, hip-hopartists Tupac Shakur and Nas (Nasir Jones). He is also teaching a class on the legacy of Jesse Jacksonthis semester, to commemorate the Civil Rights leader's 70thbirthday.

Figures like Dyson, and Brown University ProfessorTricia Rose, who authored the landmark BlackNoise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America in 1994,were at the forefront of establishing Hip-Hop studies as a viable—and yespopular—academic discipline for nearly two decades.

The reality of the presence of Hip-Hop Studies atvirtually every major college and University, unveils the "oh my, golly gee"discovery mode of so much of the reporting and controversy surrounding the JayZ class, as more manufactured, than anything else. More to the point, the attack on the validity of a classfocused on a prominent and highly influential cultural figure, who happens tobe a young Black man who has trafficked in outlier sub-cultures, seems moreemblematic of an assault on the value of a liberal education. This assaultcomes at a historical moment when the products of a liberal education, areliterally raising critical questions about the nature of inequality in Americansociety.

There are other critics, some of whom throw dartsfrom within the realm of Hip Hop Studies. They disparage Jay-Z as merely a misogynist, a hustler who promotesconsumerism and other poisonous messages to young minds that mindlessly followhim. Some of these same criticshave also questioned Dyson's knowledge of Hip Hop culture, his cultural bonafides on the discourses of the subject matter and his ability to choose theappropriate subjects. So at thesame time that conservative critics question the validity of Hip Hop studiesvis a vis Shakespeare or *yawn* classical music, other critics (the one's we'dassume might appreciate the value of such a course in the broader context ofAfricana, Popular culture, and Hip Hop studies) are quick to cast Dyson as anoutsider; to proffer Dead Prez or Mos Def as more appropriate subject matterfor this kind of course.

Well, "we don't believe you/You need more people." "Doyou dudes listen to music?/Or do you just skim through it?" Yes Jay-Z's music has many limitations, faults, and criticalflaws – some of which he is poignantly aware. But that is exactly why his life and lyrics make substantivesubject matter for sociological inquiry. His influence and impact – or what some may deem popularity orsell-out-status – are more grist for the sociological mill. In the end, the critique of the coursethat suggests that Hip Hop Studies has no place in the academy is eerily In a recent article that was less than optimisticabout the future of the humanities within American higher education, Dr.Frank Donoghue wrote, "When we claim to wonder whether the humanitieswill survive the twenty first century, we're really asking, 'Will thehumanities have a place in the standard higher-education curriculum in theUnited States?' (2010). The answerappears to be no from a myriad of places. "But there's no denying that the fight between thecerebral B.A. vs. the practical B.S. is heating up," writes NancyCook in "The Death of Liberal Arts." "For now, practicality is the frontrunner, especially as therecession continues to hack into the budgets of both students and the schools theyattend." Peddling the often-cited binaries between "cerebral" and "thepractical," the intellectual and the useful, Cook highlights the ubiquitousattack on academic enterprises that seemingly don't produce tangible results orprofits.

While commentators tend to focus on the declininginterest and place of a liberal arts education that has resulted from theincreased costs of higher education, the focus on securing a good job upongraduation, and the professionalization of higher education, the waning placeof liberal arts and humanities is not simply an organic process. It reflects a direct assault fromconservative factions within the American political landscape. In Texas, Governor Rick Perry and theTexas Public Policy Foundation called for substantial changes in the deliveryof higher education, proposing greater emphasis on teaching and research thatbenefits the state and its economic needs. Defending the call for reform, RonaldL. Trowbridge, "The Case for Higher Ed Accountability" described his viewson educational reform in the following way:

What is the value of any research endeavor to students or to widersocietal needs? Some process of evaluation must be established. If researcherswish to pursue matters that do not serve students or wider societal needs, theyare certainly free to do so, but such should be so without release time fromthe classroom.

Texas is not alone. In Florida, Governor Rick Scott recently announced hisdesire to remake public universities with greater emphasis on programs thatstimulate the economy and produce future workers in key industries. "If I'm going to take money from acitizen to put into education then I'm going to take that money to createjobs," Scottnoted "So I want that money to go to degrees where people can get jobs inthis state." The divestment ofpublic investment in the arts, human inquiry, and humanistic endeavors has beencentral to the conservative movement. Opposition to intellectual pursuits and the neoliberal emphasis onprofessionalism has had profound influence on contemporary culture.

Describing a friend who wanted to study comparativeliterature, Andrew Bast notes his initial reaction as one of "bewilderment" and"fascination," asking himself, "What in the world would be the value in that?"Capturing the hegemonic of the assault and systemic devaluing of the humanitieswithin contemporary culture, he makes "TheCase for a Useless Degree:"

I later learned that there's actually a huge value in it. Computerscience, accounting, marketing—the purpose of many majors is self-evident. Theylead to well-paid jobs and clear-cut career paths. (One hopes, at least.) Butcomparative literature, classics, and philosophy—according to the newconventional wisdom—offer no clear trajectory.

The recent spectacle and media frenzy surroundingMichael Eric Dyson's "Sociology of Hip-Hop" course points to the powerful waysthat "useless degrees" and "useless" knowledge are under attack. It also exposes the critical discoursesthat exist within Hip Hop studies – who can teach it/who is authentic enough toteach it. The media frenzy and the debate about this class reflect awell-organized attack on the humanities, liberal arts education and individualacademic FREEDOM.

Strangely enough, theinternecine squabbles about whether or not Jay-Z is fit to be taught or if Dysonis fit to teach similarly swirl in the discursive diatribes against certain"less practical" disciplines. Whatreflects back at us is an ideology that demonizes critical thought, demonizesintellectual inquiry, and silences conversations about race, gender, inequalityand other issues of social injustice. A focus here on Jay-Z or Michael Eric Dyson misses the pointbecause the class is becoming a stand-in for a larger assault on education,intellectualism, and critical thinking. The media coverage and the ensuing debates about it—on social media—reflect an overall effort to demonizethose who teach, those who educate, and those who articulate "freedomdreams." The culture wars areback and it's us against them and us against us.

***

David J.Leonard is Associate Professor inthe Department of Critical Culture, Gender and Race Studies at Washington StateUniversity, Pullman. He is the author of ScreensFade to Black: Contemporary African American Cinema and the forthcoming After Artest: Race and the War on Hoop(SUNY Press). Leonard is a regular contributor to NewBlackMan and blogs @ No Tsuris. Follow him on Twitter @DR_DJL.

Mark Anthony Neal is the author of five booksincluding the forthcoming Looking forLeroy: (Il)Legible Black Masculinities (New York University Press) andProfessor of African & African-American Studies at Duke University. He is founder and managing editor of NewBlackMan and host of the weeklywebcast Left of Black . Follow him on Twitter @NewBlackMan .

JamesBraxton Peterson is Director ofAfricana Studies and Associate Professor of English at Lehigh University and the author of theforthcoming Major Figures: Critical Essays on Hip Hop Music(Mississippi University Press). Follow him at @DrJamesPeterson.

Published on December 07, 2011 05:30

December 5, 2011

Left of Black S2:E13 | "Acting White" in the "Post-Black" Era

Left of Black S2:E13

"ActingWhite" in the "Post-Black" Era

w/Professor Karolyn Tyson and Ytasha Womack

December 5, 2011

Left ofBlackhost and Duke University Professor Mark Anthony Neal is joined in-studioby Professor Karolyn Tyson,Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at ChapelHill and author of IntegrationInterrupted: Tracking, Black Students, and Acting White After Brown (OxfordUniversity Press). Neal and Tysondiscuss the prevalence of the "Acting White" myth as it relates to Black highschoolstudents and how the myth obscures the more insidious practice of "Racialized Tracking" in PublicEducation.

Later Neal is joined via Skype© by Ytasha Womack, journalist and author of Post-Black: How a Generation is Redefining African American Identity(Lawrence Hill Books). Neal andWomack discuss the concept of "Post-Black" and what impact it has had onidentity formation among the so-called "Post-Black" generation.

***

Left ofBlack is a weekly Webcast hosted byMark Anthony Neal and produced in collaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at DukeUniversity.

***

Episodesof Left of Black are also available for download @ iTunes U :

Published on December 05, 2011 19:45

#Occupy Post-Blackness?

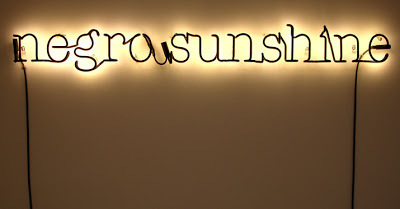

"negro sunshine"--Glenn Ligon

"negro sunshine"--Glenn LigonOccupy Post-Blackness?

by Wahneema Lubiano | special to NewBlackman

Assome of the contributors articulated in Toure's Whose Afraid of Post-Blackness, others in numerous pieces ofscholarship produced over the past decades, and still others in public discussionin various places, Blackness is both a form of chosen identity and, atthe same time, is an imposition from the larger social order. Under some circumstances thatimposition has coercive power and pressure behind it; we don't live solelywithin the terms of our own imaginations, not even in our own drama around thatidentity. That external impositionoften interrupts our identity reveries and speaks a pathology narrative aboutus and does so sometimes with and sometimes without our own consent. It is that understanding of theimposition of coercive history in the present moment that makes"post-blackness" inadequate as a rubric for accurately describing the effectsof structural racism, of white supremacy in the present. And Toure takes note of that fact inhis book.

But"post-blackness" is also situational—or, as Michael Eric Dyson asserts in theintroduction: ". . . Blackness bends to the tongue it tumbles from at any givenmoment of time" (xii). And it isin this regard that I'm interested to some great extent in specific situationalelements of the phrase's use: its use as a means to describe a moment incultural, artistic, or emotional self-understanding – yes, there indeed I cansee its usefulness and it is that usefulness that I'm addressing when I'mquoted in the book talking about why Dave Chapelle's show prompted me away fromany simple dismissal of the phrase when Toure first brought it up in ourconversation. I thought that thephrase was a useful way to describe what I saw as a kind of pre-figurativeexistence in Chapelle's work—he was performing possibilities of art—of humorand wit—that were not completely captured by the imposition of social blacknessboth across our history and in the present moment.

Yet,the phrase itself is redolent of past decades of anxiety about black art, blackcultural production—an anxiety exemplified in the 1926 fight, in the pages of TheNation magazine, between Langston Hughes ("The Negro Artist and the RacialMountain") and George Schuyler ("The Negro Art Hokum") around the burden ofrepresentation (as Stuart Hall has described it) for Negro artists. "Post-blackness" is a rubric thatreminds me that cultural producers are continually caught in the dilemma in theWest of a pressure to define themselves, to distinguish themselves, as mythicindividuals—that's the ur-narrative of U.S. individuality writ large; so, ofcourse, artists, other cultural producers, cultural critics, and we ourselvescontinually produce narratives of "generational shift"—it's a handy way to makeindividual space, to posit a conversational imperative, and have thatimperative recognized. And it doesn't much matter, when that posture is assumed,that space claimed, whether it is a new moment in fact or a seemingly new moment—the gesture ismeant to establish a possibility here and now. I find those repeated moments sociologically rich and interesting.

Butwhile I don't want to cast aspersions on that gesture, I do want to move ontosomething else that came up as we explored the gesture of Thelma Golden andGlenn Ligon, something that I'd love to talk about more, if people care to, andit's this: the social utility, the currency, of post-blackness. Let me makewhat I'm saying more concrete.

WhenToure asked me about the most racist thing that ever happened to me, my firstresponse (along with many of the other contributors he quoted) was to say thatstructural racism enacted itself in such a way that I wasn't personallyconfronted with the most racist things that had ever happened to me. But Toure pushed back on this; he pushedme to think about my earlier and younger understandings of racism: the moment priorto my arrival at an analysis of structural racism. He wanted me to speak about something that hurt way back when. So, I told a story from my high schoolyears and a bad encounter with a guidance counselor bigot because that storygave me a chance to talk about Howard University; being a student at Howard wasa moment of a kind of pre-figurative post-blackness for me. The most powerful take-away of thatstory was not the incident with the guidance counselor. What transformed my life was mydiscovery of a rich and complex existence within the terms of blackness (asituated blackness) at Howard University. I found ordinary life at Howard. (That was the saving grace.)

Myimagination's earned currency of post-blackness in turn contributed to a momentof real tension at the end of my interview with Toure when we were talkingabout Barack Obama, and he asked "How do we create more Barack Obamas?" In my response, I remember tellingToure that while Obama is certainly exceptional in that sense that he's theU.S. head of state, he is also ordinary; he is the matter-of-fact product ofhis class origins and his elite education. I know thousands of people who are proudly Black andintellectual, as Toure described him, but Obama's existence, like theirs, likeours, was largely a matter of chance and the specifics of history. An elite education produces a BarackObama or any number of other specific kinds of black—orother—intellectuals.

Itis the constraint of capitalism that restricts those numbers. My last sentence of that exchange was "AndI think capitalism is a really bad idea." I remember that Toure responded with "Wow, we'll really haveto talk about that sometime."

Thisthen might be a great time for all of us to talk about the currency ofpost-blackness within the terms of late capitalism in this moment of occupyeverywhere.

***

WahneemaLubiano is Associate Professor ofLiterature and African & African American Studies at Duke University. Lubiano is the editor of TheHouse That Race Built: BlackAmericans, US Terrain

Published on December 05, 2011 14:12

Natalie Hopkinson on "Why School Choice Fails"

Why School Choice Fails by Natalie Hopkinson | New York Times Op-Ed

IF you want to see the direction that education reform is taking the country, pay a visit to my leafy, majority-black neighborhood in Washington. While we have lived in the same house since our 11-year-old son was born, he's been assigned to three different elementary schools as one after the other has been shuttered. Now it's time for middle school, and there's been no neighborhood option available.

Meanwhile, across Rock Creek Park in a wealthy, majority-white community, there is a sparkling new neighborhood middle school, with rugby, fencing, an international baccalaureate curriculum and all the other amenities that make people pay top dollar to live there.

Such inequities are the perverse result of a "reform" process intended to bring choice and accountability to the school system. Instead, it has destroyed community-based education for working-class families, even as it has funneled resources toward a few better-off, exclusive, institutions.

In 1995 the Republican-led Congress, ignoring the objections of local leadership, put in motion one of the country's strongest reform policies for Washington: if a school was deemed failing, students could transfer schools, opt to attend a charter school or receive a voucher to attend a private school.

The idea was to introduce competition; good schools would survive; bad ones would disappear. It effectively created a second education system, which now enrolls nearly half the city's public school students. The charters consistently perform worse than the traditional schools, yet they are rarely closed.

Meanwhile, failing neighborhood schools, depleted of students, were shut down. Invariably, schools that served the poorest families got the ax — partly because those were the schools where students struggled the most, and partly because the parents of those students had the least power.

Competition produces winners and losers; I get that. Indeed, the rhetoric of school choice can be seductive to angst-filled middle-class parents like myself. We crunch the data and believe that, with enough elbow grease, we can make the system work for us. Naturally, I've only considered high-performing schools for my children, some of them public, some charter, some parochial, all outside our neighborhood.

But I've come to realize that this brand of school reform is a great deal only if you live in a wealthy neighborhood. You buy a house, and access to a good school comes with it. Whether you choose to enroll there or not, the public investment in neighborhood schools only helps your property values.

For the rest of us, it's a cynical game. There aren't enough slots in the best neighborhood and charter schools. So even for those of us lucky ones with cars and school-data spreadsheets, our options are mediocre at best.

In the meantime, the neighborhood schools are dying. After Ms. Rhee closed our first neighborhood school, the students were assigned to an elementary school connected to a homeless shelter. Then that closed, and I watched the children get shuffled again.

Earlier this year, when we were searching for a middle school for my son — 11 is a vulnerable age for anyone — our public options were even grimmer. I could have sent him to one of the newly consolidated kindergarten-to-eighth-grade campuses in my neighborhood, with low test scores and no algebra or foreign languages. We could enter a lottery for a spot in another charter or out-of-boundary middle school, competing against families all over the city.

The system recently floated a plan for yet another round of closings, with a proposal for new magnet middle school programs in my neighborhood, none of which would open in time for my son. These proposals, like much of reform in Washington, are aimed at some speculative future demographic, while doing nothing for the children already here. In the meantime, enrollment, and the best teachers, continue to go to the whitest, wealthiest communities.

The situation for Washington's working- and middle-class families may be bleak, but we are hardly alone. Despite the lack of proof that school-choice policies work, they are gaining popularity in communities nationwide. Like us, those places will face a stark decision: Do they want equitable investment in community education, or do they want to hand it over to private schools and charters? Let's stop pretending we can fairly do both. As long as we do, some will keep winning, but many of us will lose.

***

Natalie Hopkinson is the author of the forthcoming book Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City (Duke University Press).

Published on December 05, 2011 07:37

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.