Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1019

March 4, 2012

Black Women and Their Hair & Black Queer Identity in Cuba on the March 5th Left of Black

Black Women and Their Hair & Black Queer Identity in Cuba on the March 5th Left of Black

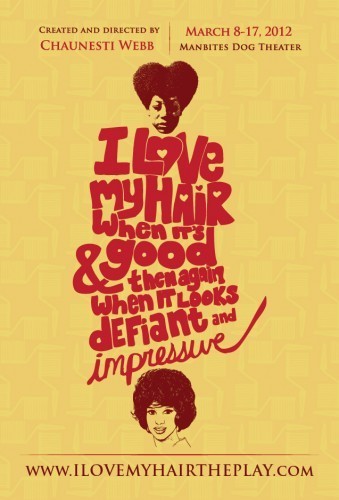

Host and Duke UniversityProfessor Mark Anthony Neal isjoined in-studio by actress and playwright Chaunesti Webb ,creator and director of the new play ILove My Hair When It's Good: & Then Again When It Looks Defiant andImpressive . Neal andWebb discuss the relationship that Black women have with their hair and thebroader cultural meanings associated with Black women's hair. Webb also talks about her play, whichopens at the Manbites Dog Theaterin Durham, North Carolina on March 8th.

Later, Neal is also joined in-studio by Yale University anthropologist Jafari Sinclaire Allen. Neal talks with Allen about his newbook ¡Venceremos?: The Erotics of BlackSelf-making in Cuba (Duke University Press). Neal and Allen also discuss thepolitical and cultural significance of Cuba to Blacks in the United States.

***

Left of Black airs at 1:30 p.m. (EST) on Mondays on the Ustreamchannel: http://www.ustream.tv/channel/left-of-black. Viewers are invited to participate in a Twitterconversation with Neal and featured guests while the show airs using hash tags#LeftofBlack or #dukelive.

Left of Black is recorded and produced at the John Hope FranklinCenter of International and Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke University.

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollow Mark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackManFollow Chaunesti Webb on Twitter: @Chaunesti Follow Jafari SinclaireAllen on Twitter: @JafariAllen

###

Published on March 04, 2012 16:42

Boyce Watkins & Michael Eric Dyson Debate the State of 'Hip-Hop' at Brown University

Published on March 04, 2012 09:44

March 3, 2012

COINTELPRO: The FBI's War on Black America

COINTELPRO: The FBI's War on Black America

dir. Deb Ellis & Denis Mueller

Through a secret program called the Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), there was a concerted effort to subvert the will of the people to avoid the rise "of a black Messiah" that would mobilize the African-American community into a meaningful political force.

This documentary establishes historical perspective on the measures initiated by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI which aimed to discredit black political figures and forces of the late 1960′s and early 1970′s.

Combining declassified documents, interviews, rare footage and exhaustive research, it investigates the government's role in the assassinations of Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, and Martin Luther King Jr. Were the murders the result of this concerted effort to avoid "a black Messiah"?

Published on March 03, 2012 15:34

Robert Glasper: "Black Radio" feat Yasiin Bey (video)

robertglasper:

Real Music Is Crash protected. Black Radio, the new album from Robert Glasper Experiment in stores now.

Published on March 03, 2012 12:16

Robert Glasper: "Black Radio" feat Yaslin Bey (video)

robertglasper:

Real Music Is Crash protected. Black Radio, the new album from Robert Glasper Experiment in stores now.

Published on March 03, 2012 12:16

March 2, 2012

Cee Lo: "All Alone Now" (produced by Waajeed)

from www.bling47.com

Never heard before Cee-Lo x Waajeed collaboration. It was written and demo'ed for the late, great Whitney Houston circa 2007. The A&R's at RCA were calling any and everybody to find a sound for (what would become) her 2009 release, I Look To You. I worked on seven or eight different versions and finally deciding on this one - with additional parts done by Simon Katz from Jamiroquai.

Published on March 02, 2012 13:57

June Jordan at the NYS Writers Institute in 2000

An excerpt from an April 27, 2000 interview with author, poet, essayist and critic June Jordan at the New York State Writers Institute (http://www.albany.edu/writers-inst/).

Published on March 02, 2012 07:06

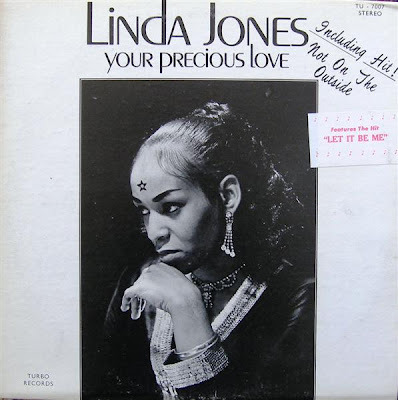

Bod(ies)Y in Pain: The Redemptive Soul of Linda Jones

Bod(ies)Y in Pain: The Redemptive Soulof Linda Jones

by Mark Anthony Neal | SeeingBlack.com

Bod(ies)Y in Pain: The Redemptive Soulof Linda Jones

by Mark Anthony Neal | SeeingBlack.com"The young lady who is theabsolute personification of soul itself"—MC, January 1970

Inhis brilliant and demanding book, In theBreak: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, theorist Fred Motendescribes Billie Holiday's Lady in Satin as a "record of a wonderfullyarticulate body in pain." (107) Recorded as Holiday's body was literally falling apart, Lady in Satin lacks the robustness andsassiness that marked so many of Holiday's earlier recordings. Here, Holiday is defiant, though,embracing death in the full bloom of her imperfection(s). As Moten writes,Holiday, "uses the crack in the voice, extremity of the instrument, willingnessto fail reconfigured as a willingness to go past…" The same could be said forSoul singer Linda Jones who recorded her most famous tune, "Hypnotized" adecade after Holiday's death. What links Holiday and the largely obscure Jones,is the violence they enacted—lyrically and musically—within the realm of their vocal performances. This was a violence, that in largepart, was a response to that which their own bodies bore witness to—how doesone sing of a body in pain?

Bornin Newark, NJ in 1944, Jones spent much of her childhood and early adulthoodstruggling with a debilitating case of diabetes, which as writer Becca Mannsuggests, "lent her career an urgency." The disease led to Jones' early demise at the age of 28—she was in themidst of successful week-long engagement at the Apollo Theater in Harlem at thetime of her death in 1972. Vocally, Jones style can only be described as "fitsof melisma"—melisma being that particular style of vocal performance that ismarked by the singing of single syllables across several pitches—and it islikely one of the reasons, including lack of national distribution, Jones neverfound a mainstream audience for her music. Though some found Jones performances as overwrought, thatwas exactly the point; Jones performed songs like "That's When I'll Stop LovingYou" or "For Your Precious Love" not simply as performative gestures, but as if she knew she was dying.

LindaJones's music demanded an emotional investment—specifically, in the lives ofblack women—that mainstream audiences, I'd like to argue, were likely incapableof making at the time. While Aretha Franklin is a seemingly clear example of ablack woman who attracted a broad mainstream audience in the late 1960s, Iwould argue that Jones's performances were inspired by a depth of pain thatFranklin's music more actively attempted to transcend. While Jones had peers inthis regard—the tragic career and life of Esther Phillips being a prime example—fewcould match her vocal calisthenics. As Rolling Stone criticRussell Gersten once commented, Jones sounded like "someone down on her knees,pounding the floor, suddenly jumping up to screech something, struggling tomake sense of a desperately unhappy life."

Whatdistinguished Jones from a figure such as Holiday, was the extent that Jonesmade palpable the influence of the Black Church on her vocal style. As such, Jones was of a generation ofvocalists, who were making the transition from the gospel choirs of their youthonto the secular music charts. SamCooke was of course a tremendous influence in this regard and in Jones's casethat influence can be clearly heard on her soul stirring performance of "That's When I'llStop Loving You" on the live recording NeverMind the Quality…Feel the Soul. Cooke's singing was a model of control andrestraint, performed under the guise of aesthetic risk-taking—Cooke arching toreach that high-note, only to float seamlessly across a phrase. Jones, incomparison, had no interest playing to the fiction that she was in control ofanything—the music, her voice and at times her own body. Both artists had the ability to presentan aura of vulnerability that made their music so palpable to audiences—Cooke'semotiveness was particularly striking for a male singer—but in Jones case she was vulnerable and each performance wasan attempt grasp a slither of the humanity that was slowly departing from her.

Jones,like Cooke and others including Franklin and Sly Stone (Sylvester Stewart)helped secularize African-American gospel ritual in the late 1950s and 1960s.In his work on the tradition of African-American gospel quartets (the specifictradition that helped produce Cooke), Ray Allen writes, "in its ritualizedcontext, gospel performance promises salvation for the believer in this worldas well as the next. Chantednarratives remind listeners of their past experiences, collective struggle,common southern and familial roots, and shared sense of ethnic identity." (The Journal of American Folklore, Summer1991). Such rituals likely allowedJones to provide her audience with some language to better interpret theaspects of her performance that were simply beyond language. In this regard, Jones literally had totalk through those aspects of her pain—testifyin' as it were—in order to bettergalvanize her audience, which was largely African-American, around her pain andby extension the pain uniquely experienced by African-American women.

Jones'desire to give tangible meaning to her pain is evident during her performance of "Things I Been Through."Ostensibly a song about a woman surviving the infidelity of a partner, Jones'sermonic break midway through thesong, transforms it into a performance of (black) women-centered resistance in which Jones seemingly relishes herliteracy of African-American church traditions. Speaking directly to her audience, Jones says,

"I don't believe you people out there no what I'mtalking about/I hear people say that it's a weak women that cries/But I dobelieve that there are very few women that can stand up under all of thispressure without out at least shedding one tear/I do believe that some of youout there have had heartaches and pain of some kind…/now if you have, I justwant you to raise your hand and say with me just one time…/now mercy, mercy,mercy, mercy, whoo, whoa"

Theirony for Jones is that it was never about simply "shedding one tear", but acavalcade of shrieks, screams and cries that found its place in the violenceshe did literally to each note she sang. As Elaine Scarry observes inher now classic book The Body in Pain(1985), one of the dimensions of physical pain is "its ability to destroylanguage, the power of verbal objectification, a major source of our selfextension, a vehicle through which the pain could be lifted out into the worldand eliminated." (54)

"ThingsI Been Through" highlights the ways that Jones' music was transgressive,particularly with regards to the connections between the black preacher andAfrican-American musical idioms. According to jazz scholar Robert O'Meally, the "black preacher presentsa rhythmically complex statement in which melisma, repetition, the dramaticpause, and a variety of other devices associate with black music are used,"noting that the "man or woman of the Word," often "drops words altogether andmoans, chants, sings, grunts, hums, and/or holler the morning message in a waythat one of [Ralph] Ellison's characters calls the 'straight meaning of thewords'." (Callaloo, Winter1988). Writing in the late 1980s,O'Meally's analysis captures a more progressive notion of the gender politicsof the black pulpit, but when Jones was recording in the late 1960s, the ideaof a black female preacher—and there were many—was still fairly radicalconcept, especially during an era when many still presumed black men of thecloth to be the logical public voices of black communities. (Think here ofJames Brown's deliberate marketing of Jones contemporary Lynn Collins as the "femalepreacher" ) "Things I Been Through" is notable because it is one of the bestexamples of the ways that Jones employed the black preacher tradition—historicallyone of the most prominent sites of black patriarchal power and privilege—in theservice of addressing black female pain and struggle. Consider the way, for example, thatJones disturbs assumptions about the relationship between physical emotivenessand weakness stating that there are "very few women that can stand up under allof this pressure without out at least shedding one tear."

Jones'music was also transgressive because of the way that it exploitedAfrican-American religious rituals for distinctly secular concerns. The same could be said about the blackliberation struggle of Jones era, which consciously utilized the discourses ofChristianity to address the political and social realities of the blackmasses. But in this regard, Jones'music was concerned with the moreimmediate concerns of pleasure and joy amidst the physical pain that largelydefined Jones' life; Jones' rendition of "For Your Precious Love",popularized by Jerry Butler exemplifies these desires. Like "Things I've Been Through" Jones'version of "For Your Precious Love" features a sermonic break, though Jonesalso provides a spoken introduction to the song. Midway through the song Jonesaddresses the women in her audience ("you know something ladies. It'sespecially you ladies I'd like to speak with"):

"Sometime I wake up in the midnight hours, tearsfalling down my face/And when I look around for my man and can't find him/Ifall a little lower, look a little higher/Kind a pray to the Lord, because Ialways believe that Lord could help me if nobody else could/But sometimes Ithink that he don't hear me/So I have to fall a little lower on my knees, looka little higher/kind of raise my voice a little higher…"

HereJones suggest that the "Lord" was not fully attentive to her needs. Though thiscould be read as a rejection of religious practice, I'd like to suggest that,given Jones' use of the African-American gospel ritual, that she was insteadrejecting the distinctly masculine concerns ("he don't hear me") in which often frame such practices. In other words, Jones is suggestingthat if such practices were fully cognizant of the lives of black women, asembodied in Jones's voice, the emotional and sexual desires of black women wouldbe addressed. In Jones' case the desire for companionship, in the midnighthour, was infused with the knowledge that any midnight could be her last.

A Case of the Runs: A Consideration ofKeyshia Cole

Whereasthe Soul singers of Linda Jones' era often strategically deployed their use ofmelisma, it can be said that many contemporary R&B singers have a case ofthe runs. For example what oftenmarked the best performances ofseminal R&B singer Luther Vandross, was his ability and willingness to leavehis audiences anxious in wait forthe deep runs that he was noted for. With a flair for the dramatic, Vandrossoften held out those runs towards the end of a song as a form artisticdenouement—a final pronouncement, if you will, of his singular vocal genius. In the case of Vandross and others ofhis generation (think here of Whitney Houston at her peak), these moment wereto be cherished—a grand gesture for the audiences that supported his music.

Suchsubtleties have largely been lost on the contemporary crop of R&B singers,who often break into frantic riffs and runs midway through the first verse, inthe process cheapening the integrity of the lyric as well as audience'sinvestment in their craft. And it's not necessarily the fault of the singers, at a moment when so-called "urban" musicis being driven by producers whose skill set is largely related to making beatsand many young singers are simply not getting the vocal direction that thedeserve. For example producerssuch as Jerry Wexler and Tom Dowd were seasoned veterans when they worked withAretha Franklin upon her move to Atlantic Records in 1967 after languishing atColumbia Records for a few years. In the case of Patti LaBelle, another vocalist well known for herhistrionics, one of her most popular recordings as a solo performer—"If OnlyYou Knew" (1983)—was the product of her collaboration with Kenneth Gamble andLeon Huff. The duo had worked with LaBelle a decade earlier on Laura Nyro's Gonna Take a Miracle and thus knew howto reign in her voice to produce, what remains, her most nuanced performance. Toooften contemporary R&B singers are working with producers who have been inthe game only a few years longer than they have.

Thislack of experience by producers and vocalists often adds to the dissonance thatresonates in the vocal quality of figures like Mary J. Blige or Faith Evans,who have become easy targets for a generation that is regularly thought to be outof tune—musically, morally, and politically—with the Soul singers of the 1960sand 1970s. But I'd like to suggestthat such dissonance is not simply the product of a generation of singers who are out of pitch—and lackingthe training to know so—but a response to the ways that post-Civil Rightsgenerations hear the world. The nostalgic harmonies of the CivilRights Generation (and their parents, many of whom are in the 80s) strikesdiscord in the lives of post-Civil Rights generations, notably GenerationHip-Hop, which have never had atangible relationship to concepts such as "freedom" and "liberation" that somein the old guard presumed was transferable. Issues like the crack cocaine epidemic, the prisonindustrial complex, police brutality, voter disenfranchisement largely based onrace and class, wage depression, lackof access to quality and affordable healthcare, misogyny, the failinginfrastructure of public schooling, homophobia, as well as a populismof common sense (which by definition is stridently conservative andanti-intellectual), have oftenleft post-Civil Rights generations grasping for straws, much the way KeyshiaCole—who I offer for your consideration—seems to frantically grasp for notes invirtually every song that she sings.

Inthe case of Cole, her singing style really is the embodiment of her on-goingdesire to hold together a life that has been fragmented by an absentee-father,a drug addicted and incarcerated mother, a difficult stint in foster care and her years as arunaway. Cole's debut recording The Way It Is (2005) provides somecontext for her near-tragic back-story, which became the basis of a realityshow (production on season two is about to begin) which captures Cole'sattempts to find some closure to her relationship with her mother and thehard-scrabble Oakland community that reared her. And though none of Cole's songs, many of which she co-wrote,speak directly to the struggles of her childhood and teenage years, those difficulties are implicit in lyrics like "I used to think that Iwasn't fine enough/And I used to think that I wasn't wild enough" (from "Love")which powerfully attest to Cole's desire to be loved—by any somebody—and thedesire to matter in society that has shown little love for young, poor, andhomeless black girls.

Itwas in fact a demo copy of Cole's "Love" that found its way to industryexecutive Ron Fair in 2003 and became the stimulus for his signing of Cole to Interscope A&M Records. As Fair recently noted, "When[Cole] sings, there's real feeling in the notes…There's pain in her voice thatis coming from reality." (LATimes,4.20.06) Much of the drama in "Love"pivots on Cole's utterances of the words "found/find" throughout the song'schorus ("Love, never knew what I was missing, but I knew once we start kissingI fououououounnd, love"). In the context of the song, found is the virtual space where Colefinds some emotional and psychic grounding. But as the tortured nature of theperformance suggest, this space offers little solace—if Cole relaxes one bit,the performance literally falls flat—as Cole is symbolically in constant turmoilwith the melodic terrain that she is largely responsible for creating.

Witha successful reality series in rotation and relative mainstream visibility forher music, Keyshia Cole has access to an audience that Linda Jones couldn'teven imagine. What the two artistsshare is a willingness to make plain, musically, the pain that has definedtheir lives, in the process creating a sensual and spiritual space which givesvoice to the wide ranging desires and fears of black women—even as so manysimply want render their music as little more than noise.

***

Aversion of this essay was published in the collection TheBest African-American Essays, 2009.

Published on March 02, 2012 06:47

February 29, 2012

Glory Road: 9th Wonder: How This Producer is Changing Hip Hop

Channel One News feature on Producer 9th Wonder & the ' Sampling Soul ' Course he co-teaches with Mark Anthony Neal at Duke University.

Published on February 29, 2012 07:07

#MoreThanaMonth: C.L.R. James

Best known as the author of The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution , Cyril Lionel Robert James was born on January 4, 1901 in Port of Spain, the largest city in colonial Trinidad. Most of his youth was spent in the village of Tunapuna, just about eight miles outside the city. His intellectual legacy is succinctly described as complex and controversial, having made significant contributions in the fields of sport criticism, Caribbean history, literary criticism, Pan African politics and Marxist theory.

--Akins Vidale

Published on February 29, 2012 06:45

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.