Mark Anthony Neal's Blog, page 1012

March 26, 2012

Death Without Sanction or Ceremony

Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis ThomasDeath Without Sanction or Ceremony by MinkahMakalani | special to NewBlackMan

WatchingSybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin fight back tears and struggle through anunimaginable range of emotions in talking about their son Trayvon Martin'sdeath, I recognized an expression I've seen only once before. It was the samelook on my mother's face nearly twenty years ago, when my brother died afterbeing shot: empty, confused, lost. Like Trayvon's parents, my mother had noreference for how to handle that depth of pain, for how to help her otherchildren confront the unimaginable, while simultaneously planning a funeral andhaving to wrap her mind around never seeing a son she had seen nearly everydayfor eighteen years.

TrayvonMartin's killing at the hands of vigilante George Zimmerman, and my brother'smurder, are similar yet quite different. Both were teenaged black boys, andboth of their killers remain free. Both were adored by their families andfriends, had gregarious personalities, and their losses have left loved onessearching for answers to explain the fulsome lives cut so horribly short. Andtheir deaths have revealed to those closest to them the fabric of a socialorder where the loss of black life figures less as a rupture than as anintricate weave in the pattern.

TreyvonMartin's killer was an overzealous, self-appointed neighborhood watch captain apparentlyintimidated by a black body in a hoodie and in possession of processed sugar; mybrother's killer a neighborhood thug who, loosing a fight, decided killingsomeone would restore his twisted sense of manhood. Both killers claimedself-defense, twisting the details of their respective nights so as to tap intoa reservoir of racial images where black men are perpetual threats to socialorder, life, and morality. That Zimmerman is a white Latino and my bother'skiller black does not detract from the similarities of their stories of fearingfor their lives. Nor does it matter that as much as Trayvon Martin's and mybrother's deaths resemble one another, they are qualitatively different.Indeed, despite the differences surrounding their deaths, that their killersdrew on identical modes for devaluing black life raises the most troublingquestions about the American racial imaginary.

I must admitto being somewhat troubled by the national response to Trayvon Martin's death,specifically, how that response has hinged on the same racial ideology thatguided both Zimmerman and my brother's killer. For me, their cases raiseuncomfortable questions not so much about their killers, but the measures bywhich a black life might, in one instance, warrant national outrage, and inanother might be better left on a pile of unprosecutable cases.

I share theoutrage that has prompted scores of blacks, Asians, Latinas/os, and whites todon hoodies in protest for justice and the arrest of Treyvon Martin's killer;the Million Hoodies for Trayvon Martin in New York; students in south Floridahigh schools walking out of class and forming human TMs on their footballfields; the Miami Heat posing for a hoodied photo, with various other NBAsuperstars and the NBA Players Association following suit and demanding justicefor Trayvon; and the scores of other Million Hoodies protests taking placeacross the country. Our collective outrage grows from the frustration ofknowing that Trayvon Martin was gunned down by a vigilante frustrated because someonehe assumed was on drugs and up to no good would be yet another "a**hole" who wouldget away.

But what if TrayvonMartin had not been a "good" kid? What if he had a juvenile record? What if hehad a felony assault case pending against him? What if all these were true, andhe still only had Skittles and a bottle of iced tea, feared the man pursuinghim, and cried out for help until he was killed? Fortunately, thesecounterfactuals are not the case, and we can have such a widespread discussionabout racial violence, stereotypes, and their real life consequences. We canhave these discussions because Trayvon's character allows for such outrage.

But when a blacklife does not fit the script of the proper, respectable black who does notdeserve such violence, such killings rarely spark moral outrage. Black life remainsin its place outside the judicial order, stripped of all sacramental qualities.The killing of black people no longer requires, as it once did, the ceremony ofthe lynch mob, nor the sanction of guilt by a court of law. It has long sincebecome routine, mundane, ubiquitous.

At the risk ofa sacrilege, at issue is not whether Zimmerman was racist or hated black people.Outside the hate crime provision that would allow federal prosecution, whether he used a racialsluris largely irrelevant to the question of where and how black life fits into thestructure of race in America. The claims and convoluted reasoning ofZimmerman's father, lawyer, and friends that he isnot racist, even if true, do not change the fact that Zimmerman operated withinthe matrices of race that deems black life a perpetual threat which only deadlyforce can halt. That Zimmerman was a vigilante helped bring this case into ournational consciousness. But as Mark Anthony Neal explains, rather than anindividual act, at issue is "the way that black males are framed in the largerculture…as being violent, criminal and threats to safety and property."

Had GeorgeZimmerman been an undercover or off-duty police officer, I seriously doubt theoutrage would be so widespread and morally persuasive. Is this overly cynical?Perhaps. But the outcry over Sean Bell and Oscar Grant, both unarmed when theywere killed by police officers who were subsequently acquitted of wrong doing(though the officer who killed Bell has been fired, a far too belated andinadequate response by the NYPD), extended little further than the cries forjustice coming from black people in New York and Oakland.

The family of Ramarley Graham, the unarmedBronx teen killed by a NYPD officer in his grandmother's bathroom, has saidthat they will hold marches every Thursday until a movement mounts around theirson's murder. The family of Byron Carter,Jr.,is currently suing the Austin police department for his shooting death,pointing out that he was unarmed, sitting in a car, and had committed no crime.Bell, Grant, Graham, and scores of others have all been tainted with a tinge ofguilt, not because of anything they were doing or had ever done in the past,but largely because the police are always already seen as justified in using deadlyforce again black bodies. Any imperfection in the black body's past merelyhelps complete the sovereign cipher.

Black womenfare no better in this racial matrix. As we have seen recently, medicalpractitioners and police often neglect black women's medical concerns andemergencies, assuming either they are engaged in illegal activity, as when Anna Browns was recentlyarrested in a St. Louis hospital emergency room for trespassing and died shortlythereafter in police custody, or are dismissed as mentally unstable, as when Esmin Green died on aBrooklyn hospital waiting room floor, where she was laying for overan hour before anyone even checked on her.

My brother wasnot, by the measures that sparked outrage over Trayvon Martin's death, a "good"kid; put differently, by the cruel calculus that requires black people approachsainthood before garnering national sympathy, he fell short. He lacked theframing to make his murder anything more than a family tragedy — gang violenceat worst, in the wrong place at the wrong time at best. And while his killerwas neither a vigilante nor law officer, that same calculus and limited moralimagination operated to make his death merely another tally in a tired and statisticallymisguided argument about "black-on-black" crime. My brother's killer wasanother young black kid. It is a story so common it is largely unremarkable asa cause for outrage, outside the black community.

When somethinglike Trayvon Martin happens, a question I always hear, without fail, from otherblack people is why don't we make the same noise when the killer is black. Itis a question born of such frustration that it belies its own reality. Blackpeople do raise their voices inprotest when we kill one another, we demand justice, we march, we protest. Butyoung black men killing other young black men is no longer compellIt is importantto remember that the very racial elements that made Trayvon Martin's killing tragicand cause of national outcry are the very elements that render invisible thekilling of less "respectable" black men by vigilantes, police, American citizens,and other black men. The racialimaginary that prompted Geraldo Rivera to blameTrayvon's sartorial choice of a hoodie as equally responsible for hisdeath as Zimmerman, that prompted Sanford police to accept an armed vigilante'sclaim of self-defense, that prompted St. Louis police to arrest a homelessblack woman seeking medical attention, is the same logic that locates a blackperson killing another black person at the margins of the judicial order, promptsjudges to sentence black defendants moreseverely when their victim is white. It is the same American racialimaginary that convinces black criminals that they are far more likely to getaway with killing a black person than with killing a white person.

If TrayvonMartin's death sparks a serious discussion about the dangers of stereotypes,hopefully that discussion considers the default settings of race in America whereblackness correlates as criminal, ignoble, predator, guilty, and whiteness asnoble, honorable, defender, innocent. Hopefully it goes beyond a mere concernfor how stereotypes mistakenly implicate decent young black men, honor studentsor college graduates, professionals and dedicated family men. Hopefully webegin to challenge the view of black women's bodies as lascivious, available,innately criminal, simultaneously diseased and impervious to pain and violence.Though I am doubtful, hopefully it brings into focus how those stereotypes, howthe structures of racial oppression sanctions the death of black kids withjuvenile records, who have poor grades, who buck authority, who are angry becauseof their life circumstances, who are too easily reasoned away as deservingdeath. I'm too cynical to believe it will happen in my lifetime, but I hopethere emerges a world moral imagination equally as outraged at the racialstructures of feeling that would sanction my brother's death as TrayvonMartin's, that would be equally moved by my mother's tears as by the SybrinaFulton's outrage, conviction, courage, and compassion.

***

MinkahMakalani is a historian andassistant professor of African & African Diaspora Studies at the Universityof Texas at Austin. He is theauthor of In the Cause of Freedom:Radical Black Internationalism from Harlem to London, 1917-1939 (Universityof North Carolina Press) and co-editor (with Davarian Baldwin) of the forthcomingEscape from New York!: The New NegroMovement Re-considered (University of Minnesota Press)

Published on March 26, 2012 20:32

Left of Black S2:E25 | The Death of Trayvon Martin and the "Fictions" of Black Leadership

Left of Black S2:E25 | March 26, 2012

The Death of Trayvon Martin and the "Fictions" of Black Leadership

Hostand Duke University Professor MarkAnthony Neal is joined via Skype© by R.L'HeureuxLewis , Professor of Sociology and Black Studies at theCity University of New York and Mary Morten ,consultant for the MortenGroup in Chicago and producer of the new film WokeUp Black which examines the lives of five Blackyouth. Lewis and Morten examine the recent shooting death of Trayvon Martin, taking into account thestereotyping of young black men. Lewis discusses the devastating effectsthat the criminalization of Black men has on women. Lastly, Morten sharesreactions to her film.

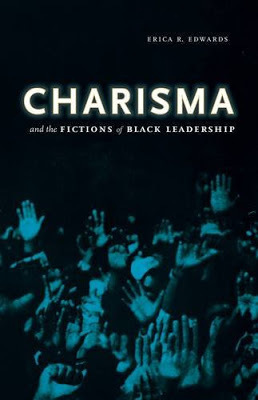

Later,Neal is joined via Skype© by Erica Edwards ,Professor of English at the University of California at Riverside and author ofthe new book Charisma: The Fictions of Black Leadership . Edwards discusses the inspiration for her book – a speech made by singer ErykahBadu at the Million Man March in 2005. Edwards examines why theleadership of a singular Black male has been deemed so important to the Blackcommunity, and explains how different time periods create a yearning for charismaticleadership.

***

Left of Black is a weekly Webcast hosted by Mark Anthony Neal and produced incollaboration with the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University.

***

Episodes of Left of Blackare also available for free download in HD @ iTunes U

Published on March 26, 2012 15:48

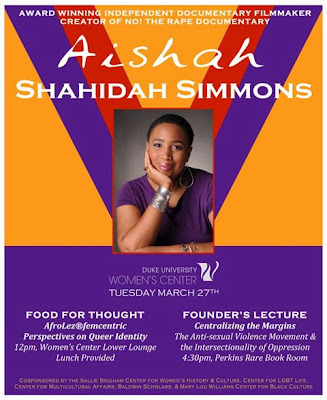

Filmmaker and Activist Aishah Shahidah Simmons to Give Duke Women's Center Founder's Lecture

Women's Center Founder's Lecture

Aishah Shahidah Simmons

Centralizing the Margins: The Anti-Sexual Violence Movement and the Intersectionality of Oppression

Tuesday March 27, 20124:30pm

Duke UniversityPerkins Library Rare Book Room

Join us for a lecture by the award-winning Aishah Shahidah Simmons, director & producer of the documentary NO! Confronting Sexual Assault in Our Community. Simmons is a African-American feminist lesbian independent documentary filmmaker, television and radio producer, published writer, international lecturer, and activist based in Philadelphia, PA. The talk will be followed with a Q&A

Published on March 26, 2012 11:56

March 25, 2012

#WHM2012: Shirley Chisholm on Her Bid for the Presidency in 1972

from the National Visionary Leadership Project :

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was the first African American woman elected to the United States Congress, where she served as the representative for the 12th district of New York from 1969 until 1982. In 1972, she was the first black woman to run for the presidency of the United States under a major party.

Raised and educated in Barbados and the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn, New York, Chisholm trained as a teacher at Brooklyn College. She learned the arts of organizing and fundraising, joining the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She developed a keen interest in politics. After a successful teaching career, Chisholm was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1964, and then in 1968 successfully ran for the U.S. Congress.

Published on March 25, 2012 17:48

#WHM2012: Shirley Chisholm on the Definition of Leadership

from the National Visionary Leadership Project:

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was the first African American woman elected to the United States Congress, where she served as the representative for the 12th district of New York from 1969 until 1982. In 1972, she was the first black woman to run for the presidency of the United States under a major party.

Published on March 25, 2012 17:41

Robert Glasper Experiement & Bilal: "Reminisce" (live in Chicago)

The Robert Glasper Experiment & Bilal- "Reminisce"

March 10, 2012

Chicago, IL @ Double Door

Robert Glasper: keys

Casey Benjamin: saxophone, keytar, vocoder, keys

Derrick Hodge: bass

Mark Colenburg: drums

BIlal: vocals

Published on March 25, 2012 11:46

March 24, 2012

Trailer: Woke Up Black (a film by Mary F. Morten)

About the Film

Arguably more than any other underrepresented group of Americans, African American youth reflect the challenges of inclusion and empowerment in the post-civil rights period. Whether the issue is the mass incarceration of African Americans, the controversy surrounding Affirmative Action as a policy to redress past discrimination, the increased use of high stakes testing to regulate standards of education, debates over appropriate and effective campaigns for HIV and AIDS testing and prevention programs, efforts to limit sex education in public schools, or initiatives to tie means-tested resources to family structure and marriage, most of these initiatives and controversies are focused on, structured around, and disproportionately impact young, often marginal African Americans. However, in contrast to the centrality of African American youth to the politics and policies of the country, their perspectives and voice have generally been absent from not only public policy debates, but media and broadcast programs. Increasingly, researchers and policy-makers have been content to detail and measure the behavior of young African Americans with little concern for their attitudes, ideas, wants and desires. This documentary will work to fill that void.

Woke Up Black followed five black youth for two years. During this time we witnessed interactions with family members, educational institutions, and the legal and judicial system. We saw the social networking that is critical to the successful development of these youth and we provided a rare opportunity to hear youth speak out on some of the important and potentially life- altering topics of the day. The film underscores the humanity that we all share with each other regardless of race or age. For some of the youth profiled, despite extraordinary circumstances, they remain hopeful.

The continuing social, political and economic marginalization of African American youth is a fact that is difficult to dispute. For example, while approximately 10 percent of non-Hispanic white children lived in poverty in 2001, the poverty rate for African American children was 30 percent. Similarly, data from the U.S. Department of Justice indicates that while 3 of 1,000 white Americans ages 18-19 are sentenced prisoners, 29 of 1,000 African Americans ages 18-19 are sentenced prisoners.

Published on March 24, 2012 18:59

Trailer: Woke Up Black (a film by Mary F. Morton)

About the Film

Arguably more than any other underrepresented group of Americans, African American youth reflect the challenges of inclusion and empowerment in the post-civil rights period. Whether the issue is the mass incarceration of African Americans, the controversy surrounding Affirmative Action as a policy to redress past discrimination, the increased use of high stakes testing to regulate standards of education, debates over appropriate and effective campaigns for HIV and AIDS testing and prevention programs, efforts to limit sex education in public schools, or initiatives to tie means-tested resources to family structure and marriage, most of these initiatives and controversies are focused on, structured around, and disproportionately impact young, often marginal African Americans. However, in contrast to the centrality of African American youth to the politics and policies of the country, their perspectives and voice have generally been absent from not only public policy debates, but media and broadcast programs. Increasingly, researchers and policy-makers have been content to detail and measure the behavior of young African Americans with little concern for their attitudes, ideas, wants and desires. This documentary will work to fill that void.

Woke Up Black followed five black youth for two years. During this time we witnessed interactions with family members, educational institutions, and the legal and judicial system. We saw the social networking that is critical to the successful development of these youth and we provided a rare opportunity to hear youth speak out on some of the important and potentially life- altering topics of the day. The film underscores the humanity that we all share with each other regardless of race or age. For some of the youth profiled, despite extraordinary circumstances, they remain hopeful.

The continuing social, political and economic marginalization of African American youth is a fact that is difficult to dispute. For example, while approximately 10 percent of non-Hispanic white children lived in poverty in 2001, the poverty rate for African American children was 30 percent. Similarly, data from the U.S. Department of Justice indicates that while 3 of 1,000 white Americans ages 18-19 are sentenced prisoners, 29 of 1,000 African Americans ages 18-19 are sentenced prisoners.

Published on March 24, 2012 18:59

The Death of Trayvon Martin and the "Fictions" of Black Leadership on the March 26th Left of Black

The Death of Trayvon Martin and the "Fictions" of Black Leadership onthe March 26th Left of Black

Hostand Duke University Professor MarkAnthony Neal is joined via Skype© by R.L'Heureux Lewis , Professor ofSociology and Black Studies at the City University of New York and Mary Morton , consultant for the Mary Morton Group in Chicago andproducer of the new film Woke Up Black which examines the livesof five Black youth. Lewis and Morton examine the recent shooting deathof Trayvon Martin, taking intoaccount the stereotyping of young black men. Lewis discusses thedevastating effects that the criminalization of Black men has on women. Lastly, Morton shares reactions to her film.

Later,Neal is joined via Skype© by EricaEdwards , Professor of English at the University of California atRiverside and author of the new book Charisma:The Fictions of Black Leadership . Edwards discusses theinspiration for her book – a speech made by singer Erykah Badu at the MillionMan March in 2005. Edwards examines why the leadership of a singularBlack male has been deemed so important to the Black community, and explainshow different time periods create a yearning for charismaticleadership.

***

Left of Black airs at 1:30 p.m. (EST) on Mondays on the Ustream channel: http://www.ustream.tv/channel/left-of-black. Viewers are invited to participate in a Twitterconversation with Neal and featured guests while the show airs using hash tags#LeftofBlack or #dukelive.

Left of Black is recorded and produced at the John Hope FranklinCenter of International and Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke University.

***

Follow Left of Black on Twitter: @LeftofBlackFollow Mark Anthony Neal on Twitter: @NewBlackManFollow R.L'HeureuxLewis: @DumiLewisFollow Erica Edwards: @Dr_Edwards

###

Published on March 24, 2012 18:52

Repacking the Invisible Knapsack: White Privilege and the Killing of Trayvon Martin

Repacking the Invisible Knapsack: WhitePrivilege and the Killing of Trayvon Martin

by Lori Latrice Martin | special to NewBlackMan

Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, a now classic work by Dr. Peggy McIntosh,addresses white privilege. Specifically, McIntosh outlines the unearnedbenefits that whites receive by virtue of their birth. Many whites, saysMcIntosh, have a difficult time seeing the daily profits associated with being white in America.She adds that while whites may acknowledge that racial and ethnic groups facedisadvantages, most have been taught not to see white advantages. She describesthe benefits associated with white privilege as "an invisible package ofunearned assets," filled with "special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks,visas, clothes, tools and blank checks."

McIntosh evenprovides us with a list some of the daily privileges she enjoys as a whitewoman that her colleagues, friends, and acquaintances of color, rarelyexperience. She says,

1. I can if I wish arrange to be in the company ofpeople of my race most of the time.

2. If I should need to move, I can be pretty sure ofrenting or purchasing housing in an area, which I can afford and in which Iwould want to live.

3. I can be pretty sure that my neighbors in such alocation will be neutral or pleasant to me.

4. I can go shopping alone most of the time, prettywell assured that I will not be followed or harassed.

5. I can turn on the television or open to the frontpage of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

In light of thetragic shooting death of 17-year-old, Trayvon Martin it's time to revisit thelist. The killing of Trayvon, an African-American male, at the hands of28-year-old George Zimmerman, is an unfortunate reminder of the continuing significanceof race. It is a reminder that the election of the nation's first blackpresident, while historic and powerful, is no match for the enduring racializedsocial system that has been at the core of American society since the birth ofthis great nation.

Many of us havebeen telling anyone who will listen, that race still matters. Such calls wereoften dismissed by blaming the victim. Unarmed black men who have been met withfatal violent force, (and the list continues to grow), are often vilified. Theywere, "in the wrong place at the wrong time" or they were "up to no good".

Trayvon Martin wasdoing what many other kids were doing on February 26, 2012. He was getting asnack and talking on his cell phone, but for Zimmerman, and others, these veryacts, when draped in blackness and clothed in a hooded sweatshirt, arousessuspicion. Now, a mother and father must bury their child.

The killing ofTrayvon Martin is heartbreaking. The failure to arrest George Zimmerman is aninsult to fair-minded Americans, simply put, it's an injustice. Thecircumstances surrounding the killing of young Trayvon Martin, adds morebaggage to the invisible knapsack. McIntosh's list must now also include thefollowing:

1. I can be confident that if I give my sonpermission to go to the store that he will return unharmed.

2. I can be sure that if my son is harmed, less than100 feet from my home, that efforts will be made to not only identify my child,but to also notify me.

3. I can be sure that the clothes my son leaves thehouse in will not be lead others to look upon him with suspicion.

4. I can be confident that, should my son be thevictim of a fatal violent crime, that law enforcement will neither assume thathe was the aggressor, nor take the word of his killer, without a thoroughinvestigation.

5. I can know that if my son is killed that thekiller will be the one tested for the presence of drugs and/or alcohol in hissystem.

6. I can be sure that, should my son be the victim ofa fatal shooting, that individuals and organizations that support me in myeffort to seek justice will not be called agitators and racial ambulancechasers. 7. If my son is the victim of a fatalact of violence and there are concerns about how the case is being handled, Ican be reasonably sure that mainstream media will provide immediate coverage. 8. If my son is killed, I can be surethat, if 911 tapes exist, they will be released without me having to collecthundreds of thousands of signatures through the use of social media.

9. If my son dies at the hands of another, I can havetime to grieve his death and not have to do the investigative work that iscommonly done by law enforcement officials.

10. If my son is killed and the identity of hiskiller is known, I can be sure that the killer will, at the very least, bearrested.

It's time to unpackthe knapsack and get rid of all this racial baggage. Justice for TrayvonMartin!

***

Lori Latrice Martin is AssistantProfessor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice where her research areasinclude race and ethnicity, wealth inequality and asset poverty. Professor Martinis currently working on a book project about black asset poverty in New YorkCity. Dr. Martin specializes in Demography, Race and Ethnicity, Race and Wealthand Community Development.

Published on March 24, 2012 15:07

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.