Thomas W. Gilbert's Blog, page 3

June 29, 2020

The WASPiness of Early Baseball: Part I

The first Amateur Era baseball clubs that we know anything about played in New York City, Brooklyn and other eastern cities in the 1840s and 1850s. Nearly all of their members were white and American-born.

Early baseball history is as white as a beach resort in Thailand. The main reason for this is that mid-19th-century journalism, which is historians’ primary source of information about contemporary culture and daily life, was aimed at a very narrow sliver of American society, the white, Protestant emerging urban bourgeoisie. Baseball’s marketing efforts were also aimed at this class, whose members had the money and leisure for adult athletics.

Baseball has always sold itself as quintessentially American. Today, we see baseball’s racial and ethnic diversity as a natural part of its Americanness. According to the ideology of the modern game, learning to play and watch baseball is an Americanizing experience that teaches our values. When the descendants of immigrants from a particular ethnic immigrant group appear in MLB uniforms, it is regarded as a sign that that group has made it and has become fully American. African Americans were almost universally excluded from baseball at the upper competitive levels from the beginning of the Amateur Era in the 1840s through the Professional Era until the middle of the 20th century. But that has not stopped Major League Baseball from casting itself as an agent of social change in its version of the Jackie Robinson story. The sport’s long history of racial exclusion cannot be denied or erased, even if MLB did set a moral example by peacefully and more or less voluntarily breaking its own color line in 1947.

What it means to be American has changed dramatically in the 175 years since baseball emerged as a national institution. It is a shock for a modern American to learn how homogeneous both early baseball and the America that created it were. This country was settled in the 17th and 18th centuries almost entirely by Protestant immigrants from Great Britain (England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, including what we now call Northern Ireland). It had negligible amounts of immigration between 1790 and 1845. African Americans, of course, were already here. A paltry 60,000 or so immigrants arrived here per decade, as the country grew from a total population of 3,918,000 in 1790 to 17,018,000 in 1840. In 1790 more than two and a half million Americans, or about 66% of the total population, were of British ancestry. The rest had ancestors from Africa (20%) and Germany (7%); smaller percentages were descended from immigrants from the Netherlands, France and other countries. Because these groups were largely Protestant, Catholics made up only 1.6% of the US population in 1790. As late as 1830, less than 2% of the US population was foreign-born.

Despite the fact that most Americans were of British ancestry, the America of the first half of the 19th century was fiercely nativist in politics. It was hostile to Great Britain – America’s bitter enemy in two recent wars -- and fearful of foreign influence generally. Baseball reflected and embodied this prevailing nativism. India, Australia, Jamaica, South Africa and dozens of other former British colonies adopted the English sport of cricket and made it their own, but not the United States. We insisted on creating our own, homemade national sport.

The first baseball players that we know anything about were amateur athletes who organized clubs like the Knickerbockers and Gothams in New York, Brooklyn and other cities in the 1840s and 1850s. At least 90% of them were native-born, white, Anglo-saxon and Protestant. Considered from the point of view of class, the members of the prominent Amateur Era baseball clubs belonged to an even narrower demographic, the forerunners of the modern middle class; very few were from high or low socio-economic backgrounds. Ironically, the earliest African-American baseball clubs that we know anything about had a similar class identity. The Pythians, an African American baseball club that was formed in Philadelphia the mid-1860s, was made up of doctors, lawyers, teachers and merchants – the kind of men who, if they had been born white, might have joined the Knickerbockers or the Gothams.

African Americans had played baseball and formed clubs before the Pythians, but the racism of the NABBP and that of the mainstream press kept the African American baseball scene in the shadows. We only know that it existed from scattered mentions in print and from the fact that competitive African American clubs like the Pythians emerged in the post-Civil War years. They could not have come from nowhere. Integrated baseball clubs may have been virtually unknown in the Amateur Era, but as the baseball movement expanded beyond the New York metropolitan area and went national, it crossed existing racial lines.

It is significant that Jews do not seem to have attracted the hatred of nativists -- or even their notice. In researching the lives of hundreds of baseball men from this period, I encountered several Jewish baseball players, but virtually no evidence of anti-Semitism in amateur baseball. This reflected the views of the emerging urban bourgeoisie of that time. New York City’s small Jewish community was long-established and thoroughly assimilated in all ways except for religion; New York’s first synagogue was founded by a group of Sephardic Jews who arrived in the 1640s, 145 years before that city’ built its first Catholic church. New York’s native-born Jews were so similar to and compatible with the Protestant mainstream that the religious identity of Jewish baseball players was hardly mentioned. This was in stark contrast to Catholics, who were feared and despised even before the arrival of hundreds of thousands of deparately poor Catholic refugees from Ireland and, to a lesser extent, Germany in the late 1840s and 1850s.

To be continued in Part II….

June 19, 2020

Baseball History Not Made OTD

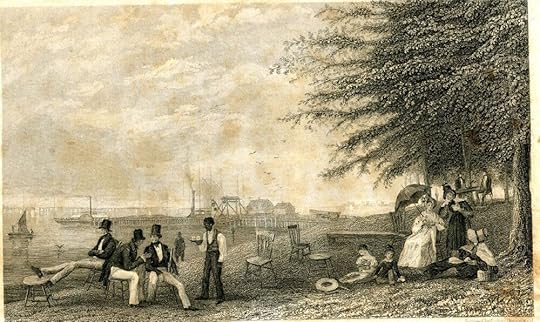

Hoboken’s Elysian Fields, the riverside resort where the first interclub baseball game was not played. This historic non-event did not occur on June 19, 1846.

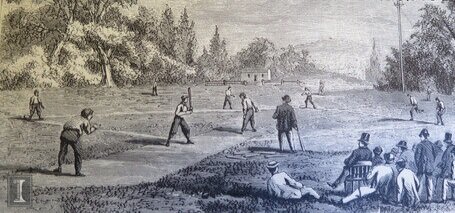

Most baseball histories will tell you that the Knickerbocker club of New York City wrote the first baseball rules and that they played the first baseball game in Hoboken, New Jersey on June 19, 1846. They will not tell you how the Knickerbockers managed to lose that game, 23-1. This is not the only problem with the Knickerbocker origin tale which, if it were a boat, would have sunk to the bottom of the Hudson a long time ago.

The whole story goes like this.

In 1845, a group of amateur athletes from New York City formed the first baseball club and published the first baseball rules. In some versions of the story, bank clerk Alexander Cartwright was the driving force behind both. All of the Knickerbockers were white men; almost all of them were native-born Protestants. Among other rules innovations, the club was the first to outlaw the practice of “soaking,” which meant smacking baserunners with a thrown ball in order to put them out. This was an important step forward in baseball’s evolution from a children’s pastime because adults preferred a game from which they did not have to limp home. Running out of playing space in New York City, the Knickerbockers wandered in the wilderness until in 1845 they found a home on the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, fifteen minutes by ferry from lower Manhattan. The Knickerbockers were influential gentlemen who popularized the game. Up sprang the Eagles, Gothams and Empires. These were followed by many more imitators in Brooklyn, New Jersey and the greater New York metropolitan area. The first players were dilettantes who put more effort into post-game banquets than into vulgar pursuits like recruiting, training or trying to win. The Knickerbockers ruled over baseball until, to their dismay, the game spread downward to the unwashed working classes. As it spread outward to Boston, Philadelphia and the rest of the country, the Knickerbockers lost control over the sport that they had made, opening a Pandora’s box of professionalism, gambling and corruption.

Two parts of this story are true. Almost all of the Knickerbockers were white American-born Protestants and the Barclay Street ferry did get you to Hoboken in fifteen minutes.

How did baseball really happen? That is a different, longer story.

May 19, 2020

When Fans Crashed the Baseball Party

We were not part of baseball’s original plan

No one invited the first American sports fans. They just showed up at baseball games in Brooklyn in the late 1850s. The unexpected appearance of large numbers of strangers alarmed both players and journalists, who were initially at a loss to understand why anyone other than a bettor would care who won a game they were not playing in.

The explanation for the crowds lay outside sports, in the economic and cultural rivalry between New York City and the then-independent city of Brooklyn. The inter-city rivalry sparked an outbreak of baseball mania among the citizens of Brooklyn. New Yorkers had been playing baseball for decades, but the Knickerbockers, Gothams, Eagles and other New York clubs played mostly intramurally. Once in a while they played a so-called “match” against another club. But their games generated little media coverage; and it was news if more than a few dozen people came to watch. Typically, the small crowds they did attract were made up largely of gamblers and bookmakers, sometimes referred to in the press as “outside friends.” They were outside because they were not baseball “insiders,” i.e., they were not players (or friends and family members of players). There was no third category.

Amateur Era sportswriters’ euphemisms for gamblers included “outside friends,” the “sporting fraternity” and “the fancy.”

In 1854 Brooklynites decided to try to beat the New Yorkers at their own game; they formed the Excelsiors, soon followed by the Atlantics, Eckfords and Putnams. It took less than four years for these clubs to reach competitive parity with New York’s big four—the Knickerbockers, Gothams, Eagles, and Empires. Spectator interest picked up, particularly in Brooklyn and particularly when a Brooklyn club faced a New York club.

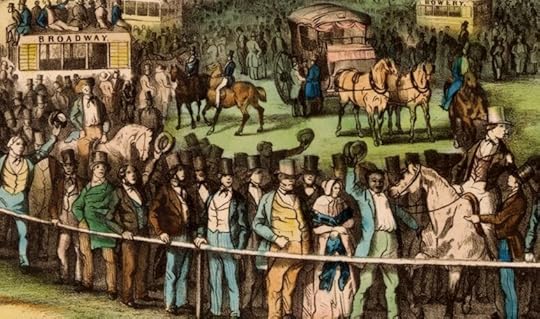

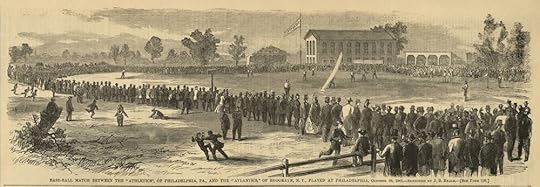

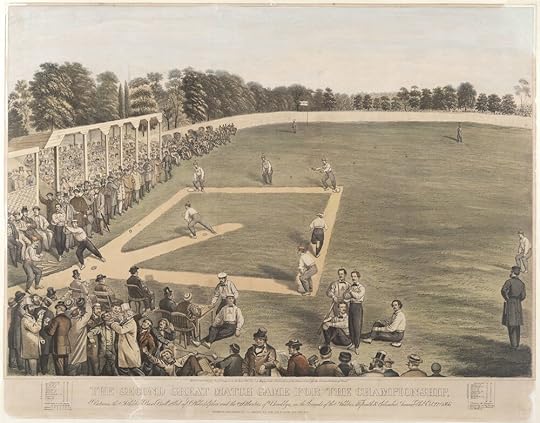

We see the first significant crowds when the Brooklyn clubs began to play more games against New York City clubs and each other. Inter-club and inter-city rivalry fanned public interest, which led to more inter-club games, which intensified rivalries. Which came first, increased fan interest or more inter-club games, is a chicken and egg question, but the connection between the two is clear. In September 1857 the Clipper warned that the big Atlantics—Gothams game would cause traffic problems. A month later newspapers reported that 3,000 people came to Carroll Park to watch Brooklyn’s Excelsiors defeat New York’s Knickerbockers, 31–13. The crowd was so big that it got in the way of the fielders. “The announcement of a passage at arms between two clubs such as these,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote, “is always a rallying cry to hundreds and thousands of the citizens of New York and Brooklyn.” In 1858 the Brooklyn Common Council challenged its New York counterpart to a best-two-of-three all-star series, called the Fashion Course series after the racing track in Queens where the games were played. Game one of the series was the first baseball game that anyone paid to see. Despite the admission charge, all three games drew never-before-seen crowds in the high four figures.

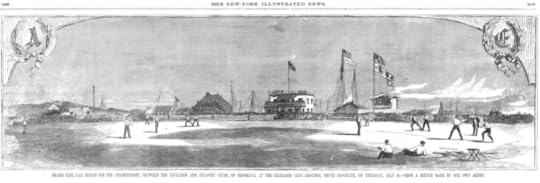

These new baseball crowds were different in size, but they were also different in character. In midsummer 1860 the baseball world was abuzz with anticipation for the championship-deciding three-game series between the two best clubs in America, the Excelsiors and the Atlantics. Both were Brooklyn clubs. But baseball insiders underestimated how much the series had captured the imagination of the general public. If you look at the background of the famous New York Illustrated News picture showing the Excelsiors playing game one of their series against the Atlantics in Red Hook on July 19, 1860, you will see groups of people standing in foul territory and others standing on the roofs of the Brooklyn Yacht Club and Excelsior clubhouse buildings across the street; newspapers also reported that spectators were perched in the rigging of nearby ships. An estimated 12,000 fans turned out—at the time, the largest baseball crowd ever. With Excelsiors pitcher James Creighton in top form, the game was never close. The Atlantics were crushed, 23–4. Game accounts from 1860 were often critical of boisterous spectators and blamed gambling, but this crowd behaved. Still, The New York Times could not help itself, crediting both clubs with having “checked the loud expressions of feeling from outsiders who were financially interested in the result.”

Game 1 of the 1860 championship series between the Excelsiors and Atlantics, played on the Excelsiors’ home field in Red Hook, Brooklyn. There is a public baseball diamond on this spot today. The buildings at center belong to the Excelsiors and the Brooklyn Yacht Club; the surrounding ships are docked along the Gowanus.

15,000 spectators came to the Atlantics’ home grounds in the village of Bedford (now the neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant) for Game 2 on August 9. The score would have been nearly identical to that of the first game, if not for a seventh-inning, nine-run outburst by the Atlantics that knocked Creighton out of the box, the first and only time this happened in Creighton’s brief career. Even the Atlantics were surprised; the rally went down in club lore as the “lucky seventh.” The Atlantics held off a 9th-inning rally by the Excelsiors to win, 15–14. On August 23 a third straight record crowd — estimated at 20,000 — came to see the rubber game of the series at the Putnams’ grounds, which were on Broadway between Greene and Lafayette Avenues in Brooklyn. Most of them were Atlantics fans. They expected to see the championship of 1860 settled, but the baseball gods had other plans.

In the early innings both clubs showed signs of feeling the pressure of playing such an important game in front of so many people. Fearful of making an out and — under the rules as they were then applied — not compelled by the umpire to swing at strikes, batters tired out the pitchers by letting dozens of good pitches go by. The Excelsiors’ Creighton threw 72 pitches in the first inning, 96 in the second, and 80 in the third, absolutely insane totals by today’s standards. With their club down 8–6 in the fifth inning, Atlantics supporters protested the umpire’s call on a close play. When the Atlantics made two errors in the top of the sixth, the crowd’s mood turned ugly. “Expressions of dissent,” wrote Chadwick in the Daily Eagle, “became so decided, and symptoms of bad feeling began to manifest itself to such a degree, that the Captain of the Excelsior nine, Mr. Leggett, than whom a fairer, more manly, or more gentlemanly player does not exist [an exquisitely Chadwickian phrase], ordered his men to pick up their bats and retire from the field.” Chadwick’s take was echoed by the rest of the press, which was uniformly sympathetic to the Excelsiors. The New York Times wrote:

The rowdy element which had been excited by a fancied injustice to [the Atlantics’] McMahon in the preceding innings, now became almost insupportable in its violence, and shouts from all parts of the field arose for a new Umpire; the hootings [sic] against the Excelsior Club were perfectly disgraceful. Mr. Leggett was supported by the Atlantic nine in his endeavors to secure order, and by their united exertions a temporary lull was secured, but, although Mr. Leggett distinctly stated that the Excelsiors would withdraw if the tumult was renewed, the hooting was again started with increased vigor, and the Excelsiors immediately left the field, followed by a crowd of roughs, alternately groaning the Excelsiors and cheering the Atlantics.

The umpire forfeited the game to the Atlantics. The Excelsiors were angry that the Atlantics would accept a championship that the Excelsiors viewed as tainted. A purported game ball was sent anonymously to Atlantics secretary Frederick K. Boughton as an insult. The Atlantics, wrote the Daily Eagle, “have chosen to recognize the ball as the one played with, and have placed it among their other trophies…the affair has created some feeling among baseball players.” History has echoed and embellished the narrative that rowdy and violent Atlantics fans, angry that they might lose their bets, were so out of control that the Excelsiors had no choice but to leave the field, and that it was unsportsmanlike of the Atlantics to accept the victory.

Amateur Era baseball players and the journalists who covered them were frightened and confused by the large crowds of fans that appeared at baseball games in Brooklyn in the late 1850s.

This version of events is heavily colored by the views of Henry Chadwick, the most influential sportswriter of the day. Chadwick had long fought for the total elimination of gambling in baseball, a campaign that struck many contemporaries as extreme and even obsessive. Could it be that what Chadwick painted as rowdy behavior by disappointed gamblers was nothing more than the enthusiasm of excited fans? None of the contemporary accounts of the disputed game alleges a single violent act by a spectator. The New York Times used adjectives like “rowdy” and “shameful,” but the only specific acts mentioned were “groaning,” “shouts,” and “hooting.” In the Clipper’s version, “the crowd began to get uproarious in the extreme, and so insulting were the epithets bestowed on the Excelsiors that Leggett decided to withdraw his forces from the field.” From a modern point of view this sounds silly. The Excelsiors walked away from a championship game because the opposing team’s fans used rough language and booed the umpire?

In the week after the disputed game, the Atlantics read one newspaper story after another that blamed their fans for the debacle. On September 1 they responded with a press statement asking, “Can we restrain a burst of applause or indignation emanating from an assemblage of more than 15,000 excited spectators, whose feelings are enlisted as the game proceeds?…if the nine is to be called off the ground on all occasions where the pressure is rather high, we think that ball playing will soon lose its most essential features…[and] terminate in the ruin of the game as a national pastime….” The Atlantics’ point of view can be summed up as: “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.”

The truth is that the biggest baseball game of 1860 was cut short because Captain Joe Leggett and his Excelsiors lost their nerve under the psychological pressure of playing in front of the largest crowd they had ever seen. What Boughton and the Atlantics understood, and what the Excelsiors and their allies in the press did not, is that the events of August 23 reflected a new reality. In 1862 a non-baseball man, William Cammeyer, opened the Union Grounds in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The first ballpark, it sold tickets and provided fans with seats, shelter, food and drink. Baseball spectators had become baseball fans and fans were now a permanent part of the game. Booing and heckling are the flip side of cheering and applause. As any professional athlete of today can tell you, both come with the territory.

April 20, 2020

The Cincinnati 20-somethings

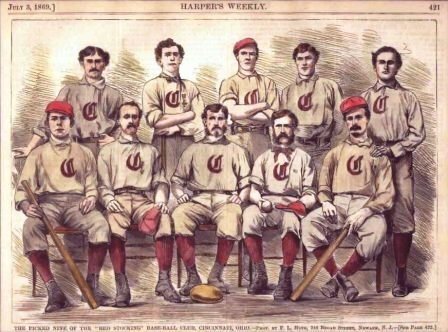

The traveling team to end all traveling teams, the original Cincinnati Red Stockings were famous in the late 1860s and they are famous today. Considered by MLB to be its forebear as the first professional baseball club, the Red Stockings were once honored on each Opening Day. Last season, every major leaguer wore a patch commemorating the 150th anniversary of the 1869 Red Stockings’ amazing undefeated season. Baseball fans who know nothing else about 19th century baseball can tell you who Harry and George Wright were, and many more remember the Red Stockings’ undefeated streak and their cross-country tours. But there is a key fact about the Red Stockings that has been largely forgotten — their youth.

In modern baseball terminology Harry Wright served the Cincinnati Red Stockings as manager, scout, strength coach, pitching coach, batting coach, bench coach, assistant GM, traveling secretary, VP of baseball operations, head of analytics, centerfielder — and their entire bullpen.

The Red Stockings were young by design. Before the first professional leagues, the top East Coast baseball clubs barnstormed, scheduling their own cross-country tours and paying for them by charging admission to games against local opponents (as well as betting on themselves — usually to win, but that is another topic). The late 1860s Cincinnati Red Stockings were the first western club to return the favor by touring the east. They were built for the road, which meant long, exhausting trips by steamboat and rail. The 1869 Red Stockings were the first to play on both coasts in the same season; they also traveled to the South and throughout the Midwest.

The Red Stockings prepared themselves by following a state-of-the-art, pre-season workout regimen designed by Harry Wright, the son of a cricket pro, who was on the cutting edge of the science of physical training. Stamina was paramount in the days before gloves, facemasks, elbow guards, 25-man rosters, modern pharmaceuticals, and Tommy John surgery. Playing captain (the job of manager did not yet exist) Harry Wright also made sure to have youth on his side. How young were Wright’s Red Stockings? A comparable club in terms of competitive level, the 1869 Brooklyn Atlantics started a 33 year-old shortstop, a 29 year-old third baseman, a 27 year-old and two 26 year-olds; their youngest regular player was 24. The 1869 Red Stockings’ roster included three 21-year-olds, two 22-year-olds, a 23-year-old, and a 19-year-old. 27-year-old pitcher Asa Brainard was the oldest man on the club except for Wright himself, who was 34. Harry Wright occasionally relieved Brainard; other than that, the Red Stockings’ lineup was virtually the same, day in and day out, for months on end. In October 1868 the club lost to the Atlantics. Their next loss came to the same club in June 1870 — 84 games later.

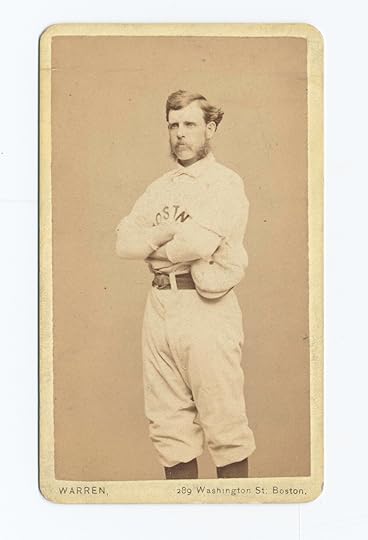

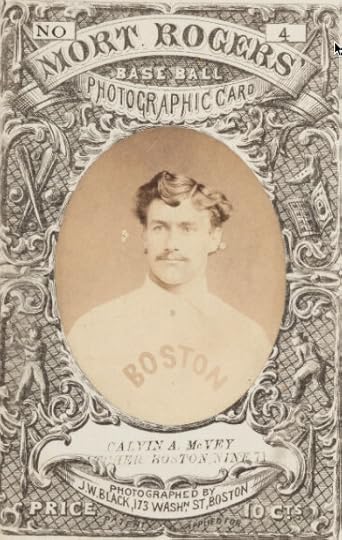

21 year-old Cal McVey in 1871. His father had to co-sign his first contract with the Cincinnati Red Stockings because he was a minor. He starred for the undefeated 1869 club as a 19 year-old.

April 16, 2020

EPIDEMIC DISEASE, BASEBALL AND HOPE

Who gave us baseball? There are many answers to this question, but here is one that you probably have not heard before: epidemic disease.

I spent most of the past several years doing research for a book on baseball’s beginnings, which meant reading a lot of newspapers from the 1830s, 40s and 50s. The America I encountered there was a strange and unfamiliar country, particularly when it comes to sports. Today we are world famous as the sports-mad nation where the four seasons of the year are baseball, football, basketball, and ice hockey—where ordinary people run and work out into their 40s and 50s; where old age and golf are inseparable; and where someone coined the word “athleisure.”

Believe it or not, Americans were once known for the exact opposite. Before the late 1850s we had no sports leagues. Newspapers did not have sports sections. Hard-working rural grownups had no time for games. Male city-dwellers had leisure, but they spent it drinking, smoking, chewing and gambling; they were allergic to exercise and went outdoors when they needed somewhere to spit. The only widely popular adult team sport was cricket, but cricket was played mostly by immigrants from Great Britain. Boxing and horseracing were popular, but Americans participated in those by betting on them.

Then baseball happened. Long played in New York City as a folk game, mostly by children, baseball began to catch on as an adult sport in the 1850s, first as recreation, second as entertainment. Baseball went national with astonishing speed. By the late 1860s, it was being played and watched from coast to coast. Baseball the sport was completely and gloriously new. It was American-made. It was not primarily about betting. And it was not yet a business; the first professional baseball league, the National Association, did not turn its first stile until 1871.

What inspired our pudgy, dyspeptic forefathers to leave the office early on a sunny day, roll up their sleeves and take up the sphere and ash? The answer is there to be found in those pre-Civil War newspapers. They are full of articles, editorials and ads urging American adults to exercise. Baseball was adopted and advocated by a broad-based sports movement that began in New York and other East Coast cities in the late 1850s. Journalists like Walt Whitman were early and enthusiastic converts. One of the movement’s principal goals was patriotic: to bring together a fragmented nation in the same way that cricket united the United Kingdom. The other was to improve America’s health. Among the leaders of the baseball movement were reforming physicians who believed that fresh air, exercise and sunlight could offer protection from yellow fever, typhoid, cholera and other mass killers that attacked 19th century America in terrifying waves.

This is another aspect of daily life in 19th century America that I struggled to understand — death at the hands of epidemic disease. This was a death that came not as a rare misfortune, and not, as in most of my lifetime and in the lifetimes of my parents and my grandparents, a death that made a kind of sense, like the death of the very old, the chronically ill, or casualties of war or violent crime. Epidemics came out of nowhere to kill indiscriminantly, without reason or explanation. They took away thousands of lives. They also took away survivors’ sense of safety and their expectation of a life span of 60 or 70 good years. In the spring of 2020, this kind of death and the fear that it brings is easier to understand.

Cities took the brunt of 19th century epidemic disease. Cholera killed roughly 3,500 New Yorkers in 1832, 5,000 in 1849 and 2,000 in 1854 – a far higher percentage of the city’s population than the Covid-19 numbers, at least so far. Wealth and privilege did not confer immunity. The 1849 outbreak killed former President James K. Polk. Like a sport, epidemic disease had a season. In July and August, the comfortable classes got out of town. Downtown areas fell silent. Mainstream medicine had no answers. Conventional medical theory held that cholera and other diseases were caused by vapors given off by decomposing organic matter, sudden changes in temperature, or eating unripe fruit. Conventional medical theory was wrong. With little scientific understanding of how infectious diseases work, doctors and public health officials had nothing to fight them with but offices and titles. Americans lived with the terrible possibility that the next epidemic might suddenly steal their lives or their loved ones.

Sports offered hope. In 1852 a man named Joseph Jones, who had recently opened Brooklyn’s only gymnasium, placed an ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “Our people,” it reads, “do not seem to understand the importance of …exercises, and they are therefore rather neglected. Whoever takes them regularly may bid defiance to consumption [tuberculosis] and all its handmaids. They develop the chest and limbs, give firmness to the muscle, and send a glow of ruddy health over the cheek. Sedentary men, go and try them!” Jones eventually gave up on gymnastics, got a medical degree and joined the baseball movement. After playing with the Esculapians, a baseball club made up entirely of physicians, Dr. Jones joined the Brooklyn Excelsiors. Elected president of the club in 1857, he recruited young athletes and built the Excelsiors into one of the top clubs in the country. He then took them on baseball’s first road trip in order to promote what was then called the New York game to the rest of the country.

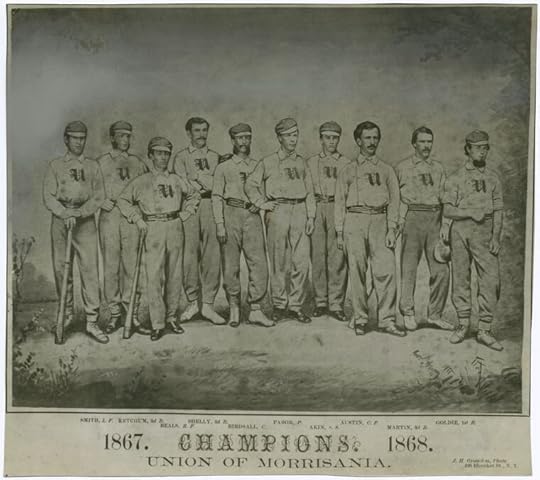

Daniel “Doc” Adams was the most important early member of the New York Knickerbocker baseball club; he was also a leading public health reformer. Adams and several other medical Knickerbockers helped create a city-wide dispensary system, supported entirely by private charity, that treated the poor and collected public health data. Adams and his allies campaigned for vaccination, better sanitation and physical education. The forgotten dispensary system is the direct ancestor of modern municipal hospital systems and health departments. During the cholera epidemic of 1866, newspaperman William Cauldwell, cofounder of the Union baseball club of then-suburban Morrisania (now the South Bronx) and a national baseball figure, published an editorial arguing that playing baseball could help fight cholera. “The vitality and strength derived from the inhalation of the pure oxygen of the atmosphere of a ball-field,” he wrote, “and the vigor imparted by open-air exercise, in which every muscle of the body is brought into play, are all conducive to a high degree of health, and of course prove strong obstacles to the approach of disease, especially of those of epidemic form, like cholera, which finds its first victims among those enervated by the lack of those very promoters of health.”

We now know that Cauldwell was wrong -- cholera is caused by drinking water contaminated with bacteria -- but the hope offered by the 19th century baseball movement was partly real. Physical fitness is not a cure-all for epidemic disease, but it strengthens the body’s immune system and the lack of it clearly makes us more vulnerable. We are told the same thing by today’s experts about Covid-19, an epidemic disease that has been particularly deadly for those who suffer from obesity and other, hidden chronic health issues. Yet in New York City, where I live, and in other cities, team sports have been canceled. I understand why I cannot watch the Yankees, but why can’t I play softball in the park? How ironic is it that Covid-19 has taken away baseball – a sport that was invented in a time of epidemic disease to give us unity, hope and health?

We could use a lot more of all three.