Thomas W. Gilbert's Blog, page 2

November 2, 2020

Election Day 1871: The Killing of Integrated Baseball

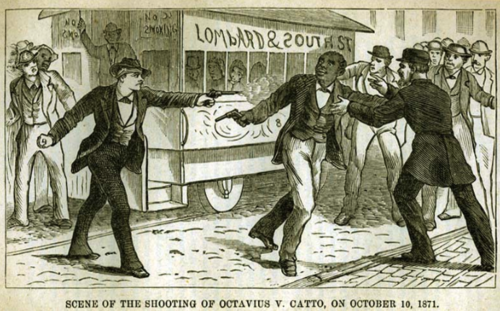

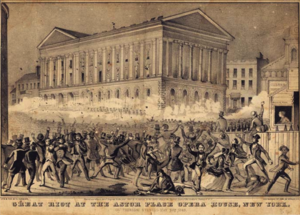

In 1870 Congress passed the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which guaranteed all American men voting rights “regardless of race, color, or previous servitude.” In many US cities the ruling Democratic Party reacted with intimidation and threats aimed at stopping African Americans, who overwhelmingly supported Republicans, from voting. On Election Day 1871 African American would-be voters in Philadelphia’s public places were harassed, assaulted and fired upon by roving gangs. Teacher and Civil Rights activist Octavius Catto was walking near the intersection of South Street and 9th, on his way home, when a Moyamensing volunteer fireman and part-time Democratic Party goon named Frank Kelly shot him dead. In 2017 a statue of Octavius Catto with his arms out and palms turned up in a questioning gesture, as eyewitnesses said they were when he died, was placed outside Philadelphia City Hall.

Catto had led successful campaigns to integrate the Philadelphia streetcar system and the Pennsylvania National Guard. But baseball was a tougher nut to crack. In 1867 Catto co-founded the African-American Pythian baseball club. The Pythians defeated local rivals and established themselves as the consensus African American champions of Philadelphia. They went to Washington, D.C., where they beat African American clubs called the Alerts — whose second baseman was Frederick Douglass, Jr. — and the Mutuals. Despite Philadelphia’s abysmal race relations, the Pythians’ success inspired civic pride in some quarters of the white press. When the African-American Philadelphia Excelsiors defeated an African American club from New York in October of 1867, the Philadelphia Sunday Mercury wrote:

“[The New York papers] apply the title of Champions to the Excelsiors, and then abuse and ridicule them, after the fashion of New York. The Pythians, also of this city, are the recognized champions among colored organizations, and should they ever conclude to visit New York, an opportunity will be afforded Philadelphia defamers to see a well-behaved set of gentlemen.”

Amateur baseball was always looking for a few “well behaved gentlemen.” So far, all of them had been white, but baseball’s national governing body, the NABBP, had no actual policy banning African Americans. None of the early African American clubs in New York City or Brooklyn had ever tried to join. In October 1867 the clubs of the Pennsylvania State baseball association, part of the NABBP, were holding their annual convention in Harrisburg. The president of the association happened to be Philadelphia Athletics delegate Hicks Hayhurst, a Quaker and racial liberal who had umpired Pythian games. The Pythians decided that the time was right to test amateur baseball’s principles. They sent Raymond Burr, the son of Abolitionist newspaper editor John Pierre Burr (who was rumored to be the unacknowledged child of U. S. Vice-president Aaron Burr and a Haitian servant) to Harrisburg to apply for admission to the association. Burr was politely treated, but after voting to approve 265 out of 266 applications for membership, the nominations committee postponed consideration of the Pythians until the following day. That night, no doubt trying to head off a divisive conflict, Hayhurst convinced Burr to withdraw the Pythians’ application by telling him that it had no chance of winning in a public vote.

The nightmare of white discomfort was averted, but men of influence in baseball decided to make sure the issue never came up again. At the NABBP national convention, held soon after in Philadelphia, a committee including New York baseball men James Whyte Davis and Dr. William H. Bell authored a resolution that explicitly barred any club with one or more African American members. When it passed, baseball’s first color line was drawn.

After Catto’s 1871 assassination the Pythians announced that “in the death of Octavius V. Catto our organization has lost its most active and valued member.” They promised that they would carry on his struggle for “truth, justice and equality.” But they would not do it through baseball.

Sex and Sox

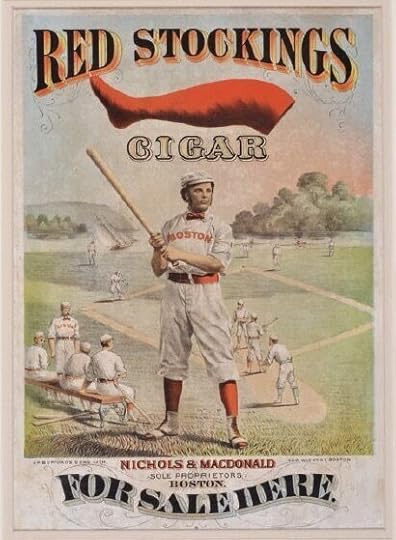

OG Sox: The 1867 Red Stockings invented the modern socks-forward baseball uni

The original Cincinnati Red Stockings made history — below the knee.

By winning a lot of games in a row, the amazing, road-tripping, undefeated 1869 Red Stockings helped make baseball a truly national sport. They were also the first baseball club to wear the knicker-style uniform, the prototype of every baseball uniform worn today, and they made the bright red stockings that it exposed into an outrageously popular trademark. Baseball clubs ever since have imitated the Red Stockings by wearing distinctively colored or patterned socks. Fans today may not realize it, but the White Sox, Reds and Red Sox are not the only professional franchises who took their names from the color of their socks. So did the Kansas City Royals (named after the color royal blue), the St. Louis Cardinals (named after the color cardinal red) and many others.

In the 1860s well-dressed women wore wide, bell-shaped skirts that brushed the ground. They wore a lot of clothing underneath, including stockings -- wool, silk or cotton, depending on economics and the weather -- but in those days stockings were not normally on public display. We exaggerate the modesty of our Victorian ancestors; a glimpse of stocking was probably not as shocking as Americans today think. Showing more lower leg, however, had erotic impact, judging by photographs of mid-19th-century prostitutes, who often pose lifting a skirt to the knee and staring insolently at the camera.

The male calf also had appeal. The Red Stockings’ uniform pants stopped at the knee; below that the players wore tight red wool stockings. In 1869 the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, “It is easy to see why they adopted the Red Stocking style of dress which shows their calves in all their magnitude and rotundity. Every one of them has a large and well-turned leg and every one of them knows how to use it.”

Celebrity, of course, can have more sexual power than the human body or even sex itself. In the middle of their sensational undefeated 1869 season, the Cincinnati Red Stockings came to Philadelphia, where a newspaper described what happened after the Red Stockings defeated the local Athletics, 21-4.

“The evening came, and the ball players sought their couches at a respectable hour and arose yesterday morning refreshed, reinvigorated and with clear heads. How far they had succeeded in winning the especial admiration of some of Philadelphia’s fair daughters may be determined from a slight circumstance. During Sunday night the rain had fallen pretty freely, and thus an excuse was afforded several of the Philadelphia darlings for raising their skirts, just to keep them from trailing on the wet sidewalk in front of the hotel at which the Cincinnati folks were staying, and to show just enough of pretty ankles, enclosed in red stockings, which, despite the intense heat of the day, the proprietors of the aforesaid pretty ankles had procured and donned to assure the visitors that they had influential “friends at court”... the fine-looking young men composing the Cincinnati nine had gained, beyond a doubt, the favor of the ladies.”

September 21, 2020

Volunteers: Baseball Goes to War

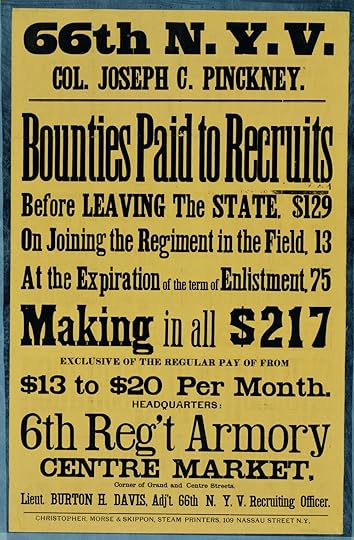

Union army units like the 66th NY volunteers were recruited by men of influence in the overlapping worlds of politics, volunteer firefighting and baseball.

Because of how volunteer regiments were recruited and created, the cultural and social connections among baseball clubs, volunteer fire companies and citizen militia units were imported to the military. Countless fire companies and militia units enlisted en masse and became regimental companies. Members of baseball clubs were already concentrated in particular state militia units before the war. Regiments such as the First and Second New York Fire Zouaves were recruited from New York City and Brooklyn fire companies, whose membership overlapped with that of dozens of baseball clubs. The New York Historical Society has a collection of Civil War military recruitment posters. A look through them shows how closely intertwined Amateur Era baseball was with other areas of life that today could not be more separate from the bubble that is the world of professional sports.

Joseph C. Pinckney, fervent Abolitionist, important early member of New York state’s Republican party, Civil War commander, man-about-town and star second baseman for the Union club of Morrisania, NY.

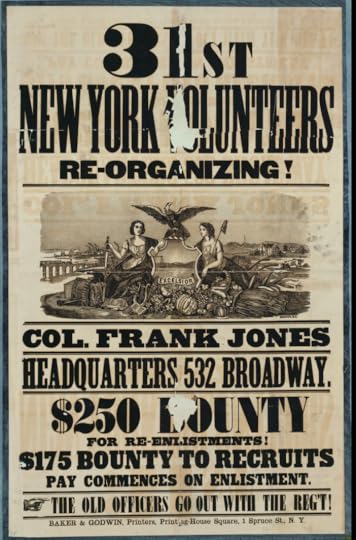

Remember that the vast majority of soldiers on both sides of the Civil War were volunteers. Imagine that you are a young man in his twenties who is walking the streets of Manhattan. What kind of sales pitch might persuade you to enlist? Recruitment posters typically make three kinds of promises. The first is money. “Bounties Paid to Recruits,” read a poster for the 66th New York Regiment, “$129 BEFORE Leaving the STATE.” Recruits are promised a total of $217 in bonus money, in addition to regular army pay of $13 to $20 per month. The second is safety, in the form of seasoned leadership. “The Old Officers to Go Out With the Regiment!” reads a poster for the 31st New York Volunteers. The third is a credible and trustworthy commander, a man with popularity and social capital with whom the rank and file could feel a sense of personal connection and loyalty. (Irish immgrants signed up by the thousands to fight with their hero Michael Corcoran; among German-American troops the popular catchphrase was “I fight mit Sigel (German-born General Franz Sigel).”

Frank Jones was a member of the Excelsiors, the first baseball club in Brooklyn. The war brought him to Washington, DC. In peacetime he recruited New York baseball stars for the Washington Nationals, giving them sinecures or no-show jobs in the Treasury Department.

Many of these commanders were important figures in the worlds of politics, citizen militias and volunteer firefighting. Some were also baseball men. On a recruiting poster for the the 66th NY, the name of Colonel Joseph C. Pinckney appears in large type in the second line from the top. Pinckney was a Republican politician, but he was also a well-known star baseball player with the Gothams and the Unions of Morrisania. For the 31st NY, the colonel whose name appears in large black letters on recruitment posters is Frank Jones, member of the Excelsior club of Brooklyn and future officer and backer of the Nationals, Washington, D.C.’s most important early baseball club.

September 20, 2020

Civil War Baseball as Remembered

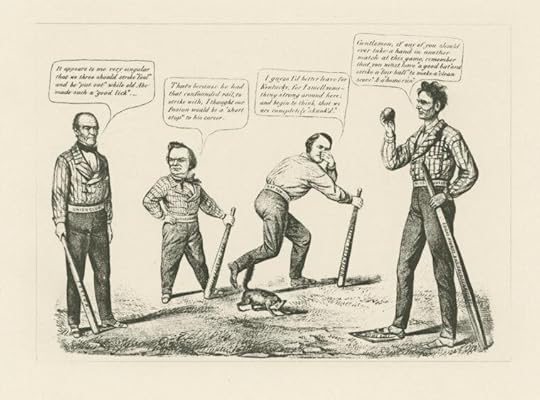

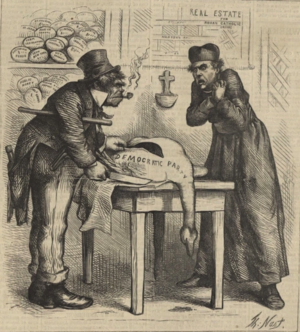

A baseball-themed political cartoon from 1860, when baseball was far more popular in the East and North than elsewhere.

How exactly the Civil War helped, hurt or otherwise affected the young sport of baseball is a difficult historical question. We have many anecdotes about baseball games played by Union troops, Confederate troops — even some between the two. But most of these were published decades after the fact, when hearts and minds and softened. That matters. Here is an example.

In his 1899 memoir Captain John G. B. Adams of the 19th Massachusetts tells the story of a Civil War “baseball” game that he recalls playing in in 1863. Other accounts verify that the game was played, but because the Massachusetts game was sometimes referred to as baseball, we cannot be entirely sure which bat and ball game Adams is talking about. You would think that soldiers from eastern Massachusetts in 1860 would be playing the Massachusetts version — a game native to the Boston area that was ultimately dropped in favor of the New York game (what we call “baseball”) — but then again, some men of the 19th Massachusetts came from southern Maine, where, oddly enough, they played the New York game. And their opponents were drawn from a Michigan unit that was full of transplanted New Yorkers. You have to be skeptical that Adams really saw Confederate troops playing baseball, but his story is even more far-fetched if he meant that they were playing the Massachusetts game, “just the same as we were.”

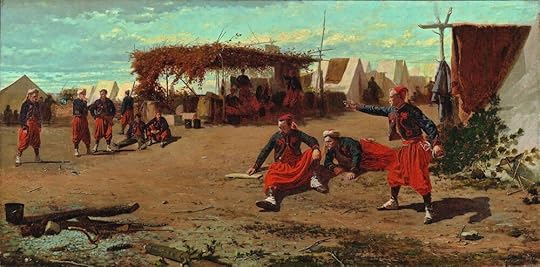

Winslow Homer’s painting of Union soldiers passing a lull in the fighting with a game of quoits.

“While in camp at Falmouth [Virginia],” Adams writes, “the baseball fever broke out...It started with the men, then the officers began to play, and finally the 19th challenged the 7th Michigan to play for sixty dollars a side...The game was played and witnessed by nearly all of our division, and the 19th won. The $120 was spent for a supper, both clubs being present with our committee as guests. It was a grand time, and all agreed that it was nicer to play base than minie ball. What were the rebels doing all this time? Just the same as we were. While each army posted a picket along the river they never fired a shot. We would sit on the bank and watch their games, and the distance was so short that we could understand every movement and would applaud good plays.”

It is easy to hope that this story is true.

September 17, 2020

A High School Baseball Player Invented Football -- What?

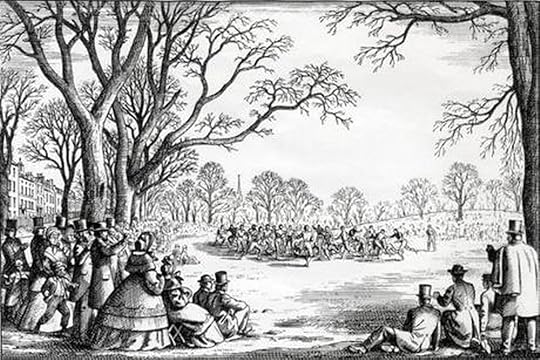

The Oneidas playing American football — or its weird ancestor — on the Boston Common in 1862

In baseball’s early Amateur Era the biggest rivalry was Brooklyn versus New York City. The Boston equivalent was the town and gown rivalry between the Lowell club and Harvard. For decades Boston had played its own homegrown bat and ball game, called the Massachusetts Game, but in the 1860s the Lowells and Harvards took up the newly arrived New York version — the game that we now call baseball.

The Lowells began as a junior club sponsored by wealthy printer John Lowell; Lowell came from southern Maine, which was baseball country because of its commercial ties to New York. The original Lowells were boys who attended Phelps’s, Dixwell’s, Boston Latin and other Boston secondary schools. The first Harvard club was founded in 1863 by members of the Class of 1866. This is where New Yorkers come in.

The roots of the Harvard club were in Phillips Exeter, a New Hampshire prep school attended by Harvard ‘66 students George Flagg and Frank Wright. As Wright recalled, during Latin class, a classmate passed him a note suggesting they start a baseball club. “A majority of the fellows wished to form a club to play Massachusetts baseball...but a few of us who hailed from New York State carried the meeting in favor of the new game, then called the ‘Brooklyn’ game.”

Double-threat founding father Gerrit Smith Miller

Born near Syracuse in upstate New York, Gerrit Smith Miller was a 16-year-old student at Dixwell’s Private Latin School when he joined the Lowell club in 1861, its first season. (He went on to study at Harvard, but out of loyalty would not play in their games against the Lowells). Dixwell’s school was near the present location of Emerson College at 20 Boylston Place — about twenty steps from the Boston Common, where prep and high school boys of the day got black eyes and muddy clothes playing various informal rugby-like games. While still at Dixwell’s, Miller amused himself in the baseball off-season by organizing a club called the Oneidas, which played its own brand of football, with tackling, passing and end zones. The Oneidas’ game is generally considered to be the ancestor of the game played by today’s NFL. Yes, the father of American football was a teenage baseball player.

September 16, 2020

The Father of Baseball -- All 13 of Them

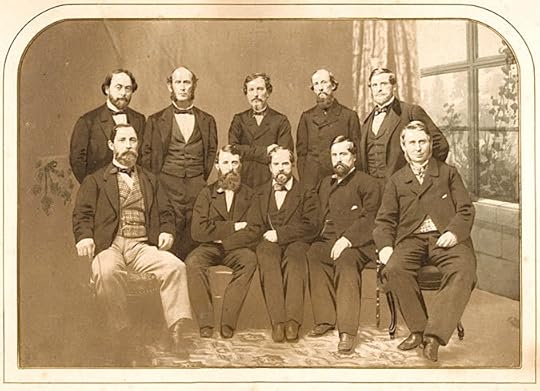

All of these guys have been called the “Father of Baseball” in print at least once. The ones with the + sign have it written on their graves.

Robert Ferguson

Billy McMahon

John Joyce

H Chadwick +

A Doubleday

A Cartwright +

Doc Adams

Duncan Curry +

Harry Wright +

T G Van Cott

William Wheaton

Albert Spalding

Louis Wadsworth

September 12, 2020

Baseball AND THE RAILROAD

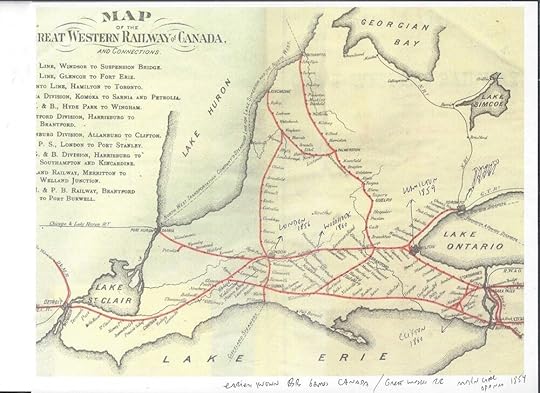

The earliest baseball clubs in Canada were founded in cities along the Great Western Railway, which brought thousands of New Yorkers and other Americans to the Midwest.

The spread of baseball beyond the New York metropolitan area in the 1850s and 1860s was a railroad story. The first railroad lines were local; they were designed not to connect to other lines in other places. American bat and ball games (including baseball, town ball and the Massachusetts game) also began as local, unconnected subcultures, peculiar to their own cities or regions. But both were systematized, standardized and organized into instruments of unification. The New York and Harlem Railroad brought New Yorkers to the suburbs of Yorkville, Harlem, Morrisania and the rest of Westchester County; clubs appeared in all of these places that played baseball. Baseball sometimes followed expanding railroad lines instead of heading straight to large population centers. Little Piermont -- 1856 population about 1500 - was the site of Rockland County, New York’s first known baseball club. It was not an important place from any point of view except one; it was the eastern terminus of the Erie Railroad, which ran from Dunkirk, New York, near Buffalo through the southern tier counties of New York State. Until the Erie Railroad was connected to Jersey City, passengers and freight were ferried between Duane Street in Manhattan and a pier at Piermont. For a brief and shining moment, Piermont was an important node in the New York metropolitan area transportation network. And during that moment railroad engineer Henry Belding, who was in Piermont to work on the Erie Railroad, founded the Belding baseball club. The small Vermont towns of Irasburg, Brandon and Pawlet all had baseball clubs before the state’s largest cities because they were on advancing railroad lines. If you draw a line on a map connecting Hamilton, Burlington, St. Thomas, London, Ingersoll, Guelph and Toronto -- southern Ontario cities where Canada’s first baseball clubs appeared between 1856 and 1860 -- you will be tracing the lines of the Great Western Railway, which linked Niagara Falls, near Buffalo to Windsor, near Detroit in 1854.

When baseball set out to conquer the nation, it took the train. Just as Major League Baseball could not have expanded to the west coast in the 1950s without the new Boeing 707 jet airliner, which made cross-country air travel practical, neither the famous Red Stockings’ national tours of 1868-1870 nor the coming national professional baseball leagues would have been possible without the transcontinental railroad and the other vast railroad systems of the 1860s and 1870s. From double-headers (a train with an engine on both ends) to schedules to making the grade, professional baseball is full of terminology that springs from its long, intimate relationship with railroad travel.

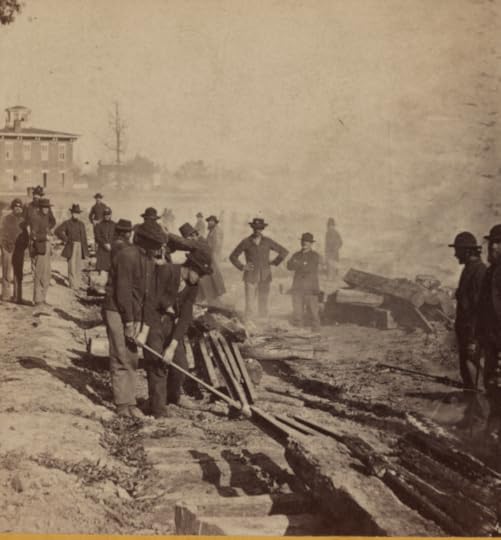

The destruction of the South’s railroads by Union troops in the Civil War set back the sport of baseball in Dixie for at least a generation. Ironically, this photo was taken by Henry T. Anthony, a member of the Knickerbocker baseball club of New York City.

The famous Cincinnati Red Stockings were built specifically to travel. Multi-city baseball tours were an idea that dated back to the Excelsiors’ 1860 trips to upstate New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, if not further. During the Civil War years, clubs regularly travelled between the east coast cities. As railroads expanded, longer tours became possible. In 1840, when adult New Yorkers were starting to form the first baseball clubs that we know much about, New York State had a total of 453 miles of railroad lines. In 1850 that number had risen to 1,409 and in 1860 -- the year of baseball’s first multi-city tour -- to 2,682. There was similar growth in Pennsylvania and Virginia. Railroad growth in the booming upper midwest was even more dramatic. In the two decades between 1840 and 1860, Indiana went from 20 miles of railroad tracks to 2,163; Illinois from 26 to 2,799; and Ohio from 39 to 2,946. Not long after settlers, war and trade brought baseball to these states, the established eastern clubs arrived — by train. An extension of the old custom of sporting clubs, militias and firehouses exchanging visits and hospitality, the original purpose of these trips was to spread the game. In the post-Civil War years, they became more about profit, but they continued to popularize baseball. The tours also pointed the way, with a big bright arrow, to baseball’s future as a national entertainment business. Essentially, this is what a modern professional sports league is: a series of road trips organized and structured to produce a credible champion. Even when they are both playing at home, we still call the two sides in every baseball game from Little League to the major leagues the “home team” and the “visitors.”

September 11, 2020

Baseball in a Civil War POW Camp

In 1862 Union POWs at the Saiisbury, NC Confederate prison camp celebrated July 4th by playing baseball for a silver medal. The two sides were the New Yorkers and everybody else — officers only.

In 1862 fifty-one-year-old Captain Otto Boetticher of the German-American 68th NY celebrated the Fourth of July in a North Carolina POW camp. A highlight of the festivities was a baseball game played by prisoners. A professional painter and lithographer who had served in the Prussian Army, Boetticher was known for military subjects; his 1851 work, Seventh Regiment on Review, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows the famous New York City militia unit parading on Washington Square. Boetticher returned to the city after the war, serving as a German consular agent, and died there in 1886. He drew a poignant panorama of the Salisbury prison camp that includes the baseball game of July 4th, 1862. The drawing served as the basis of the above color print, published in 1863. Dozens of the participants, the umpire, scorers and spectators are clearly portraits of individuals. The players on one side are wearing red ribbons pinned to their their shirts.

Boetticher conveys prison life with some humor. Pigs are being fed. Oblivious to the baseball game, Confederate prison guards are throwing dice. A prisoner is caught stealing food from the camp kitchen. Behind a low wall in the distant shadows we get a glimpse of a man squatting on a latrine. In 1912 the Buffalo Enquirer reported that Chicago Cubs owner Albert Spalding had discovered a copy of the Boetticher print and was looking for former Salisbury POWs to help him identify its subjects. “Those who have carefully examined the drawing,” wrote the Enquirer, “feel convinced” that two of the men in the picture were the famous Generals Phil Kearny and Franz Sigel. Convinced or not, they were wrong; neither one was ever imprisoned at Salisbury (and Kearny would have been pretty conspicuous with his one arm). But the officer with the good seat, the rightmost spectator, is clearly Colonel Michael Corcoran, the charismatic Irishman who commanded New York’s Fighting 69th. Both the uniform details and the unusual forward sweep of his hair are correct.

In his memoirs Oberlin College Classics professor Giles W. Shurtleff, one of the second basemen in this game, describes playing daily baseball games at Salisbury. He recalled one particular game in which his team held a late-inning, one-run lead. “A long fly ball was hit toward the Captain in right field,” Shurtleff said, “but in order to catch it and win the game, he was forced to cross the ‘deadline,’ the demarcation between the prison yard and escape. In that instant he had to decide if he would cross the line, with the very real risk of being shot, or let the ball drop harmlessly to the ground giving advantage to the other team. He opted to make the catch because he was fairly certain the guard on duty that day would not shoot. They won the game.”

July 27, 2020

Baseball, Fathers and Feminism

Joseph B. Jones (in top hat and black coat) served as president of the Brooklyn Excelsiors and president of the National Association of Base Ball Players. He was also a boxer, gymnast and feminist.

The sport of baseball famously has many founders. Among them were physicians and public health reformers who led a national movement to convince our notoriously pallid and sedentary ancestors that exercise would improve and prolong their lives. In the first half of the 19th century they experimented with boxing and gymnastics before settling on baseball — a game that until the late 1850s was played almost exclusively in New York — as the sport that would appeal to the widest cross-section of Americans. The story of the 1850s and 1860s is how they converted Philadelphia and Boston to the New York game, and ultimately succeeded in creating our first national sport.

A young woman working out with Indian clubs, which were imported by British soldiers from South Asia. Early 19th century feminists were divided on whether women should practice light exercise like calisthenics or compete in more strenuous sports like baseball. Emma Willard, Mary Lyon and other founders of the first women’s colleges stood in the latter camp.

Dr. Jones was not the only prominent member of the American sports movement to fly in the face of Victorian mores by advocating exercise for female as well as male Americans. This was politically risky. After opening Brooklyn’s first gym worthy of the name in 1849, Jones hired trousers-wearing English feminist Madame Beaujeu Hawley to teach exercise classes for females. This provoked a controversy that sounds like something out of modern Tehran or Riyadh. Defending himself from a storm of criticism from Brooklynites who considered it indecent for women and girls to work up a sweat, and especially for men to see them, Jones reassured the public that he would keep the sexes strictly separate at his facility. To cover his glutes, he also published a statement in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper from Abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher and other free-thinking Brooklyn mullahs attesting to the moral probity of gymnastics for women and girls.

Newspaper publisher Thomas Fitzgerald, also a committed Abolitionist, co-founded the Athletics club in 1859 and played a central role in spreading baseball to the city of Philadelphia. Among his friends and allies were the feminist writer and editor Sarah J. Hale, who co-founded Vassar College and supported physical education and sports for women and girls. Students at Mount Holyoke and other women’s colleges formed some of the earliest collegiate baseball clubs. The first Harvard baseball club was founded by the class of 1866; Vassar had two clubs in 1866.

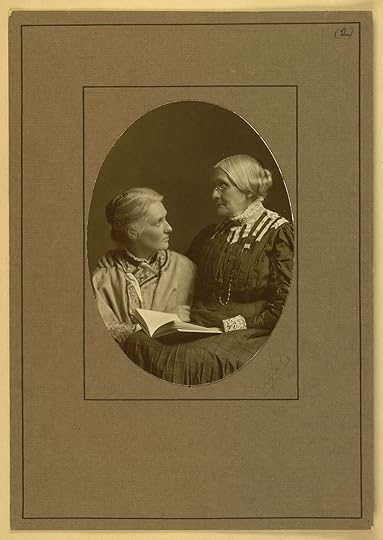

Anne Fitzhugh Miller and Susan B. Anthony

Another important baseball proselytizer, Gerrit Smith Miller was a 16-year-old student at a Boston prep school when he became an original member of the Lowells, Boston’s second baseball club, in 1861. Born in Peterboro, New York, Miller was named after his grandfather Gerrit Smith, a 19th-century land reformer, station master on the Underground Railroad, Temperance activist and supporter of the vote for women. Gerrit Smith was also a friend and ally of political radical Thomas Ainge Devyr, the father of Brooklyn baseball star Tom Devyr. Gerrit Smith’s daughter and Gerrit Smith Miller’s mother, Elizabeth Miller was the first woman to appear in public in bloomers, the baggy pants worn as a political statement by 19th-century feminists, and co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

In August 1868, Thomas Fitzgerald’s Philadelphia City Item ran the following story.

“At Peterboro, writes Mrs. [Elizabeth] Cady Stanton, there is a baseball club of girls. Nannie Miller, a grand-daughter of Gerrit Smith, is the captain, and handles the bat with a grace and strength worthy of notice. It was a pretty sight to see the girls with their white dresses and blue ribbons flying, in full possession of the public square, while the boys were quiet spectators of the scene.”

Nannie Miller, who grew up to be the famous feminist Anne Fitzhugh Miller, was Gerrit Miller’s sister.

July 7, 2020

The WASPiness of Early Baseball: Part II

Baseball’s ethnic, racial and religious ancestry can be summed up in one sentence. The overwhelming majority of Amateur Era (pre-1871) baseball players that we know anything about were native-born white American Protestants.

The place to look for the reason is baseball’s birthplace, New York City, and its homeland, mid-19th-century America.

Doggett’s city directory of 1845/46 gives a picture of New York City’s religious makeup at the time of baseball’s emergence as an adult sport. It makes pretty surprising reading for those of us who think of New York as a place of diversity and a haven for immigrants. Doggett’s lists 205 houses of worship. Sixteen are Roman Catholic and 9 are synagogues. One hundred-eighty are Protestant, including 21 Baptist, 5 Congregational, 17 Dutch Reformed, 4 Quaker, 3 Lutheran, 24 Methodist Episcopal, 29 Presbyterian and 8 listed as “African-American Protestant.” Expressed in percentages, synagogues made up (4.4%) of all houses of worship; Catholic churches made up 7.8%. Compare this to today, when there are 296 Roman Catholic parishes in New York City, serving 2.8 million people, almost 30% of the city’s total population. If we read the New York City newspapers of the 1830s, 40s and 50s, we see that the African-American baseball scene, which we know from circumstantial and other evidence existed and even thrived, is virtually ignored. The reason for this is the lack of interest on the part of the mainstream press --- and, presumably, its readers -- in anything that African-Americans were doing, saying or thinking. We also see that baseball’s surprising tolerance of the Jewish community and its unsurprising intolerance of Roman Catholics, the Irish in particular, reflected the attitudes of the larger community.

The New York Clipper of 3/27/1869 ran a reminiscence of life in New York in the 1840s and 1850s by “Paul Preston Esq.,” the pen name of Thomas Picton, who was born in New York City in 1822. He writes: “Few persons can imagine, nowadays, the intensity of animosity which pervaded the native-born population, in my younger days, against professors of Romanism, and in particular against those of Irish origin…strange to say, fraternal privileges, universally extended to the fair daughters of Judea by the haughtiest landowner’s son were invariably withheld from those of Romanish communion, while to intermarry with a [Catholic] belle, in this wise tabooed, was regarded as an enormity, surely followed by social outlawry.”

According to an article in the New York Times of 3/24/1854, “Probably 6,000 Jews are to be found in the city of New York. Their children attend the same schools with our children, and, until we reach their religious peculiarities, there is little to distinguish them from others of our citizens.”

These views were largely shared by the urban bourgeoisie of Boston, Philadelphia and other eastern cities that took up baseball and formed clubs on the New York model in the late 1850s and the 1860s. The vast majority of members of the Amateur Era clubs in those cities were native-born white Protestants. (Reflecting the early German immigration to Pennsylvania, In Philadelphia a noticeably higher percentage of tbaseball players carried German surnames). The rare foreign-born exceptions – mostly players who were born in Ireland or in the UK – were exceptional in other ways as well. Like Al Reach, Andy Leonard and Fergy Malone, they had emigrated to the US in infancy or as young children, played at the very end of the Amateur Era, or both. A handful of Latinos played baseball for top clubs in the 1860s, but, like Esteban Bellan of the Troy Haymakers, all were sons of the Cuban bourgeoisie, whose families had previous close ties to the US and who were sent to New York secondary schools to escape social and political unrest in Cuba. Like the early Jewish players, they were profoundly similar in class identity to their WASP counterparts.

American nativism was intensified by the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Irish Catholic potato famine refugees in the period of 1845-1851, along with large numbers of new Germans, many of them Catholic, but this did not begin to affect the institution of baseball until well into the professional era. The reason for this is that, both then and now, people who immigrate from non-baseball playing countries after late childhood almost never master baseball as players. The impact of the sons and grandsons of Irish, Italians, Poles and other immigrants on baseball would have to wait at least one or two more generations, as well as for the advent of professionalism, which eroded the sport’s nativist culture and values by incentivizing the selection of players by merit.