Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 114

October 27, 2015

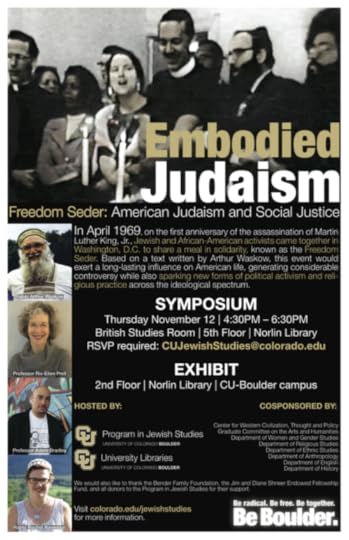

Symposium on the Freedom Seder

The very first time I went on a Jewish Renewal retreat -- a week-long retreat at the Elat Chayyim Center for Jewish Spirituality, which was then in Accord, NY -- I spent my mornings studying Jewish meditation with Rabbi Jeff Roth (now of the Awakened Heart Project) and my afternoons talking tikkun olam /healing the world with Rabbi Arthur Waskow of the Shalom Center. I knew Reb Arthur's work already because I had read his book Godwrestling. I suspect that's where I first learned about the Freedom Seder.

The very first time I went on a Jewish Renewal retreat -- a week-long retreat at the Elat Chayyim Center for Jewish Spirituality, which was then in Accord, NY -- I spent my mornings studying Jewish meditation with Rabbi Jeff Roth (now of the Awakened Heart Project) and my afternoons talking tikkun olam /healing the world with Rabbi Arthur Waskow of the Shalom Center. I knew Reb Arthur's work already because I had read his book Godwrestling. I suspect that's where I first learned about the Freedom Seder.

The Freedom Seder was held on the third night of Passover, April 4, 1969, the first anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King, in the basement of a Black church in Washington DC. About 800 people took part, half of them Jews, the rest Black and white Christians. (If you're interested, the text of the original 1969 haggadah is available online -- and here's a terrific NPR piece: In Freedom Seder, Jews and African Americans Built a Tradition Together.)

This November, the Freedom Seder and its legacy will be celebrated at Colorado University in Boulder with their second biannual Embodied Judaism Symposium, Freedom Seder: American Judaism and Social Justice on Thursday, November 12 from 4:30PM – 6:30PM on the CU-Boulder campus. The symposium will explore American political activism and religious practice in the wake of the 1969 Freedom Seder.

I'm honored to be included among the speakers at that symposium. Reb Arthur will be there and will speak about the original Freedom Seder and its impact on twenty-first century struggles for social justice. I'm planning to speak about how the Freedom Seder used the particularistic Jewish language and frametale of the seder in order to express a vision of justice and a world redeemed, as well as the impact of the 1969 event on the last few decades' worth of feminist seders.

Adam Bradley, Associate Professor of English and Founding Director of the Laboratory for Race and Popular Culture at CU-Boulder, will explore how the 1969 Freedom Seder’s core principles of grassroots social action, prophetic vision, and cross-racial collaboration are linked to the burgeoning hip hop culture of the mid-1970s. And Riv-Ellen Prell, Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota, will address the cultural politics of the Freedom Seder and how the event challenged particularist understandings of Jewish ritual, recasting Jewishness as a radical platform for building bridges across race and religion.

I'm looking really forward to this symposium and to hearing what all of the other presenters have to say. If you're in the area and this sounds interesting to you, please join us! The Embodied Judaism Symposium is free and open to the public. However, space is limited, and RSVPs are required, so please email CUJewishStudies@colorado.edu or call 303.492.7143 to reserve a spot.

Jay Michaelson's "The Gate of Tears"

Have you ever felt that a book's arrival in your life was a perfectly-timed gift? That's how I felt when I received my copy of Jay Michaelson's The Gate of Tears, new this month from Ben Yehuda Press. As I delved into the book, that sense deepened.

Have you ever felt that a book's arrival in your life was a perfectly-timed gift? That's how I felt when I received my copy of Jay Michaelson's The Gate of Tears, new this month from Ben Yehuda Press. As I delved into the book, that sense deepened.

This book was not easy for me to read, but I am grateful for its presence on my bookshelves, and I know that I will read it again.

"Joy and sadness are not opposites. Sometimes, they coexist, like two consonant notes of a complex yet harmonious chord," Jay writes. Most of us would probably prefer joy, and probably try to avoid sadness. Sadness isn't something we want to focus on. That's part of the backdrop against which the book is written:

At our contemporary moment, the ordinary sadness that is part of a life richly lived is often stigmatized, shamed, deemed a kind of American failure... Perhaps counterintuitively, it is the surrender to sadness that causes it to pass -- not the suppression of it.

I know that I have shamed myself for my sadness. I so value gratitude that when sadness arises I can feel like I'm failing. Sometimes my mental monologue has demanded, what's wrong with me that even with all of these gifts in my life I still feel sad? But I've come to see that being aware of sadness is not a sign that something is wrong with me -- rather that something is right.

I try to cultivate gratitude: first thing in the morning, last thing before sleep, and a million moments in between. And that doesn't cancel out the fact that learning to sit with sadness can help me connect with God. As Jay writes, "The art of being with sadness, and other unwanted houseguests of the mind, brings about an intimacy with what is -- what the mystics call the One, the Divine, the Beloved."

The book is clear that there's a difference between sadness and depression:

[A]s someone who has experienced depression at times in my life, I feel qualified to say that sadness is not the same thing. Depression is a medical condition, a function of brain chemistry. It can be crippling, devastating, bleak. It makes it hard to live one's life. Subjectively, I experienced it as a dullness, a kind of lessening, or graying, of all emotion. Sadness, on the other hand, is part of being human. So is loss, pain, and loneliness. These are not veils in the way of feeling; they are feeling.

A thousand times yes. Longtime readers know that I experienced postpartum depression in the months after our son was born. I have experienced depression in other ways at other moments in my life. Sadness and depression are not the same, at all. Depression flattens me and makes life feel un-livable. Sadness is not like that.

Sadness hurts, of course. Sadness can come in waves so intense they take my breath away for a time. But sadness passes, and in its wake I feel the joy of being alive. And sometimes I can feel that joy even while the sadness is present. That's the experience at the heart of this book, for me.

Or, in Jay's words, "When the desire to banish sadness is released, sadness cohabitates with joy, and gives birth to holiness. More moments merit being named as Divine. After surrendering the fight to stay afloat, I drown, but find I can breathe underwater." There can be release in letting go.

The book is a series of short vignettes, somewhere between essays and prose poems. (Jay's poetic sensibilities are no surprise to me; I reviewed a collection of his poems here in 2008.) The structure serves this material well. One can sit down and read the whole book in one gulp, but there's also merit in reading a few short pieces and sitting with them for a while before moving on.

From time to time this book provoked resistance in me. For instance, this suggestion:

Think of something you truly want. Now inhabit the sense of not getting it. Really visualize yourself not meeting your most profound desires. Skip the silly stuff -- cars and whatnot -- and go for the real.

That hit me where I live. The idea that the things for which I most yearn may not be possible -- I feel that like a kick to the solar plexus. The idea that the people I love may never get the things for which they most yearn hits me even harder. Everything in me resists this. This is one of the places where the book challenges me. "That is the gate of tears: to experience the heart, not to minimize it," Jay writes. (I initially misread that as "to experience the hurt, not to minimize it," which works too.)

To experience it, but not to wallow. "Wallowing in sadness is the opposite of entering the gate of tears." Wallowing means telling myself stories about my sadness, entrenching myself in my own narrative about what the sadness is and what it means. Entering the gate of tears, in my understanding, means just experiencing the sadness. Letting go of my need to tell stories about it. And maybe thereby letting it be a doorway through which I can come into contact with (what I call) God.

It is a small thing, really, this redemption of ordinary sadness. But when I am able to catch its advent, and when I am fortunate to have the time to accommodate it, what might previously have led to a spiral of fruitless soul-searching and desperate efforts to change what has naturally come to pass is instead an occasion for a quiet celebration... I would let this be my communion, my kiddush: the sanctification of the ordinarily despised, the blessing of a heart no longer in search of its mending.

What really gets me in this passage is the final two clauses: "the sanctification of the ordinarily despised, the blessing of a heart no longer in search of its mending." What a beautiful turn of phrase, and what a beautiful emotional place to be able to inhabit. I have a hard time letting go of my desire to mend my heart's broken places (and an even harder time letting go of my desire to mend the broken places in my loved ones' hearts). But I understand why the kind of equanimity he describes is a gift.

Equanimity doesn't mean not feeling sadness or happiness -- it means being with what is. And sometimes "what is" is sadness, and that's okay. "[S]adness is God in a minor key," Jay writes. "It's not just okay to feel sad -- it is holy to feel sad, if that is what is happening now. When I push away sadness and try only to think happy thoughts, I am denying 'What Is' -- denying God."

It's easy to be tempted to try to think only happy thoughts. And there are times when there is value in changing my mental-emotional "channel," in making the conscious decision to cultivate gratitude or to focus my attention on something else in order to break the hold which a particular emotional state might have on me. But there's also value in sitting with "what is" and finding the holiness therein.

And sometimes "what is" is heartbreak. I think of R' Elliot Ginsburg's teachings about tsubrokhnkeit -- the spiritual art of living with broken-heartedness. Jay cites some of the same Hasidic texts which Reb Elliot used in teaching that class on middot (spiritual qualities), including this one from the Kotzker:

"There is nothing so whole as a broken heart," the Kotsker rebbe taught, knowing from his own life the taste of melancholy and the way in which the heart's yearning opens us to experience Reality. The Jewish path of is one of love and tears and fear and doubt. The broken heart is what I mean by God's heart breaking.

I resonate with this idea that it is the heart's yearning which opens me up to experience God. Speaking of yearning: I have recently fallen in love with the opening line of the traditional liturgy for havdalah, the ritual which brings Shabbat to its close. (Havdalah can be a time of profound yearning. It opens up a paradoxical way to feel most keenly the consummation of Shabbat even as Shabbat departs.)

Havdalah begins with a quote from Isaiah 12: הנה אל ישועתי אבטח ולא אפחד / hinei el yeshuati, evtach v'lo efchad -- "Behold, the God of my salvation; I will trust and will not be afraid!" I've been sitting with these words a lot lately, so I noted with particular interest the times in this book where Jay cites that same line. He writes:

So the liturgy says not to be afraid. I read it not as promising that pain will be kept at bay, since that is impossible, but rather that God will be with you wherever you are, even in the pain; that there will remain accessible a reservoir of unconditional love that is either Divine or, more remarkably, a natural capacity of the human heart. The trust in this faculty of mind (or, if you prefer, grace of God) is a kind of salvation.

This is always here.

Reading these lines, I find myself thinking of times when I have had to bid farewell to a Shabbat which felt like a spiritual oasis from which I do not want to depart, or times when I have had to part from someone I love. How my heart feels cracked-open with yearning and sorrow! How much I wish I could stop time! Sometimes the ache is so powerful it feels as though it could wash me away.

But even as I grieve the parting, I know that I would rather have the togetherness and then part -- I would rather have the Shabbat and then have to weep when it ends -- than not. At those moments, my sadness contains within itself a kernel of profound joy. I ache and there is joy in the aching. For me, that's the most accessible manifestation of the intermingling of sadness and joy which Jay describes.

What resonates for me in this book probably says as much about me as it does about the book. I suspect I will find that over time, different passages will leap out at me. But for now, these are the parts of the book which I most wanted to share here.

Buy the book at Ben Yehuda Press or from your favorite bookseller.

October 24, 2015

Untie my tangles

I come to you tangled.

I come to you hurting

and afraid, my muscles

in knots, my heart sore.

You won't judge me

even if I cry myself ugly.

Even if my circuits are wired

strange. Even if I ache.

Run your gentle fingers

through me. Loosen

the snarls, the snares.

Remind me how to breathe.

Tell me I'm not too much.

Invite all of me

to walk with you. See me

and I become whole.

This is another poem of yearning which will probably become part of Texts to the Holy.

It riffs off of the prayer Ana B'Koach, which asks God to untie our tangled places. And the final stanza hints at a verse from this week's Torah portion, Lech-Lecha. In Genesis 17:1 we read that God says to Avram, הִתְהַלֵּךְ לְפָנַי, וֶהְיֵה תָמִים - "Walk before Me, and be תָמִים / tamim." Though that English doesn't really capture the reflexiveness ofהִתְהַלֵּךְ / hit'halech, which might mean something more like "walk with yourself" or "bring your whole self to walk." And what is tamim? Some translations say "pure;" some say "whole-hearted." In this context, I like to translate it simply as "whole."

October 23, 2015

Brought to you by diner coffee

I think of myself as pretty good at working with people remotely. I was a relatively early adopter, internet-wise. I've been online for well more than 20 years. I spent three years on the board of directors of a nonprofit organization with no physical address, working with colleagues all over the globe day after day via purely internet-based tools. And yet I can't deny that there is a different energy, a special spark, which arises when I can sit down with someone face to face. Maybe especially if our brainstorming is fueled by a neverending stream of surprisingly decent diner coffee.

This is a photograph of my current favorite diner. This diner is on a relatively nondescript Main Street sort of highway in a smallish upstate New York town. We happened on it purely because the town in which it is planted is roughly midway between where I live and where my ALEPH co-chair lives. And besides, its chrome and mirrors gleam so appealingly on a sunny day! (And when you walk inside, you're greeted by a giant statue of a guy holding a gargantuan coffee mug.) Every so often, when we can swing it, we get in our cars and we each drive a couple of hours, and this is where we meet up.

It's enormous, and although there's frequently a healthy crowd, I've never seen it full. Maybe that's why they don't seem to mind when we show up, order breakfast, and then spend hours with laptops thanking the waitstaff when they come to top off our cups. It was at this diner, some months ago, that we first dreamed up a list of hopes for ALEPH six months, a year, three years hence. It was at this diner recently that we opened up that plan again and marveled at how many of those hopes and dreams are (with help from Board, staff, teachers, and the Holy One of Blessing) coming to pass.

Lately we've been joking that when we issue that State of Jewish Renewal report next summer at the ALEPH Kallah, we should indicate on the flyleaf that it is brought to you by this diner's neverending stream of coffee. Most recently it's where we met with Rabbi Andrew Hahn, "the Kirtan Rabbi" (about whose work I have posted before), to talk about next summer's Kallah, innovation space and the integration of serious text study with heart-centered Renewal spiritual technologies, and more. We only make it there every few months, but it's already becoming my diner-office-away-from-home.

I don't mind working remotely. On the contrary: I love the fact that when the ALEPH Board meets, I see friendly faces (on my computer screen) who are in a variety of locations and time zones. I love the fact that I get to work with terrific colleagues around North America and around the world. But there really is no substitute for facing a friend across a formica diner table, warming one's hands on a cup of joe in a satisfyingly chunky diner mug, making to-do lists and riffing off of each other's ideas, and then together -- dual laptops open, shared document cursor blinking -- diving in and getting to work.

October 21, 2015

ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour: Next Stop, Philly!

This weekend, my co-chair Rabbi David and I are off to Philaldephia for the next stop on the ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour! (That link goes to our new webpage describing the listening tour -- what we're doing, why we're doing it, where we're doing it. Every time I look at the graphic at the top of that page I want a Listening Tour t-shirt...)

This weekend, my co-chair Rabbi David and I are off to Philaldephia for the next stop on the ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour! (That link goes to our new webpage describing the listening tour -- what we're doing, why we're doing it, where we're doing it. Every time I look at the graphic at the top of that page I want a Listening Tour t-shirt...)

Like our stop in Boston a few weeks ago, this weekend will feature some events which are open to the public. On Friday night we'll have Kabbalat Shabbat services on Friday night at Mishkan Shalom, which will feature some Torah from R' David and some poetry from me. On Saturday morning we'll be at P’nai Or, where the plan calls for Torah study at 9:15am and davenen at 10:30. There will be a 1pm lunch and a 2pm open mike session at P'nai Or where we will harvest hopes, dreams, and feedback from the community. If you're in the area, have an investment in the future of ALEPH and/or Jewish Renewal, and have an interest in adding your voice to the chorus, we hope you'll join us.

There will also be some events over the course of the weekend which are for a more intimate group of curated guests. We've done this in both of the cities where we've traveled thus far (New York and Boston) and both times it's been pretty extraordinary. Philadelphia is one of the centers of Jewish Renewal life, so this time around our balance of self-identified Renewalniks to others is different than usual. Over the course of our weekend in Philadelphia we'll be meeting with Rabbi Arthur Waskow of The Shalom Center, Rabbi Deborah Waxman (President of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College), Rabbi Shawn Zevit (of Mishkan Shalom and the ALEPH Ordination Programs va'ad), Rabbi Marcia Prager and Hazzan Jack Kessler (of P’nai Or and the ALEPH Ordination Programs va'ad), and more.

As in all of our Listening Tour stops, we're making an effort to listen to "insiders" as well as "outsiders." We want to hear from those who have been part of Jewish Renewal for a long time, and also those who are new to Renewal, and also those who perhaps don't see themselves as part of Renewal per se but are doing the kind of meaningful, heart-centered, innovative re-creation of Judaism with which we resonate. Our conversations thus far have been both broad and deep.

And we continue to make a spiritual practice of receptive listening. We want to hear what you need to tell us about ALEPH and about Jewish Renewal, whether it is praise or critique or a mixture of the two. We want to know your hopes and dreams for the Jewish future, and your suggestions for how to work toward that future. We commit to holding your feedback in confidence. And we will do our best to incorporate everything we're learning and hearing into the State of Jewish Renewal report which we intend to offer next summer at the ALEPH Kallah (July 11-17 in Fort Collins, Colorado -- join us!)

On a purely personal level, and as someone who collects different prayer experiences, I'm especially excited about our Shabbat davenen plans. P'nai Or was founded in the early 1980s by Reb Zalman z"l, and is now led by Reb Marcia and Hazzan Jack. Reb Marcia is the dean of the ALEPH rabbinic program (and Hazzan Jack runs the ALEPH cantorial program), so I've davened with them many times over the years, though never in their home community. And Mishkan Shalom is home to A Way In, an initiative which focuses on Jewish mindfulness practice, of which I have been a longtime fan from afar.

(Reb Marcia and Reb Shawn together run the Davenen Leadership Training Institute, a two-year liturgical leadership training program about which I blogged frequently. DLTI was one of the best experiences I had in rabbinic school, and continues to deeply shape not only how I lead davenen but also how I enter into prayer in order to be able to lead others there. Getting to spend a weekend davening with the two of them is my idea of a good time.)

And I'm looking forward both to the open mike and to the curated sessions. It's inspiring and humbling to sit with people -- some of whom have renewing Judaism longer than I've been alive! -- and take in their insights about where Jewish Renewal has been and where we might yet go. And it's exciting to sit with people who are collaborating with us in the big-picture work of revitalizing the Jewish landscape and making heart and spirit central to Jewish experience -- regardless of whether they consider themselves part of "organized Jewish Renewal" -- and share hopes and dreams for what the Jewish future might hold and how we might work together in holy service to shape that future.

Our Philadelphia weekend will be co-hosted by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, P’nai Or, and Mishkan Shalom. If you're in the Philadelphia area and are able to join us for Friday night or Saturday morning services, and/or for the open mike after Shabbat lunch, I hope to see you there.

(For more on this, check out An Update on the ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour at Kol ALEPH.)

October 20, 2015

To Shabbes

I want to plead "don't go!"

though I know you'll return.

I trust the future I can't see.

My strength is in your song

even when I'm not certain

how to play all the chords.

When you're with me

every channel opens,

sweetness courses through.

My unlovely thin skin

becomes a cloak of light.

I breathe the air of Eden.

Return quickly, beloved!

I'm counting the days.

I carry you in my heart.

This is another poem in the series of poems of yearning and longing which I think will probably become part of the chapbook which currently has the working title of Texts to the Holy.

There are a lot of references here to the prayers of havdalah, the ritual which sanctifies separation between Shabbat and week -- especially to the opening prayers which precede the blessings. Also to a teaching which riffs off of the fact that the Hebrew words for "skin" and for "light" are homonyms. (Find it at the end of this post.) There's also a hint at Yedid Nefesh, which I think is one of our tradition's most beautiful songs of yearning for the Beloved.

October 19, 2015

Mincha with Mary

If you had been among the leaf-peepers in a particular small town in southern Berkshire county on Saturday afternoon, you might have seen two rabbis wearing peacoats and kippot, sitting on a stone bench beside a shrine to Mary.

If you had been among the leaf-peepers in a particular small town in southern Berkshire county on Saturday afternoon, you might have seen two rabbis wearing peacoats and kippot, sitting on a stone bench beside a shrine to Mary.

You might have caught snatches of Shabbat afternoon nusach (the melodic mode for that particular time of day on that particular day of the week) on the wind, along with the falling yellow leaves and the (unseasonal! too early!) snow flurries.

You might have seen those two people stand, and take three steps toward the east (not toward the statue), and bend and bow. You might have seen them rocking gently in prayer. You might have seen them laugh upon reaching the blessing which references winter weather.

And you might have seen them return to the bench, shoulder to shoulder, visibly amused at the sweet absurdity of davening Shabbat mincha prayers together alongside (not praying to, but praying beside) a statue of a nice Jewish girl, a spiritual ancestor from a couple of millennia ago.

And then you might have seen them say farewell to Mary and depart down the sidewalk, admiring the late afternoon light gilding the far-away tops of the hills, off to whatever adventure awaited them next.

October 18, 2015

White light, rainbows, and the soul: a teaching on parashat Noach

When our ancient ancestors saw rainbows, what must they have imagined? Today's Torah reading suggests that they saw rainbows as God's mnemonic device, a reminder of the promise that God would never again try to destroy all life.

When our ancient ancestors saw rainbows, what must they have imagined? Today's Torah reading suggests that they saw rainbows as God's mnemonic device, a reminder of the promise that God would never again try to destroy all life.

Today most of us would probably say that rainbows exist because of scientific principles. Raindrops refract sunlight, dividing it into its constituent wavelengths. White light becomes red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet.

Rainbows take something ordinary -- plain white light -- and reveal the extraordinary hiding within it. All of those colors in the spectrum are always already part of every sunbeam, but we don't see them until the raindrops refract the light.

And that scientific explanation takes me right back to theology. The kabbalists, our mystics, use this as a metaphor for God. God is singular, God is One -- like white light. But for those who have eyes to see, God's qualities fan out like the colors of the rainbow.

Hidden within the oneness of white light are the seven colors of the rainbow. And hidden within the Oneness of God are lovingkindness, strength and boundaries, harmony, endurance, humble splendor, generativity, and Shekhinah -- what our mystics called the seven most accessible qualities of God.

This year, the image of the rainbow teaches me about balance. When white light meets raindrops we see the spectrum of colors in perfect balance across the sky. No one color drowns out the others: they're all there. All of these qualities are part of God, and in God too they need to be in balance.

Too much gevurah (judgement) might lead to a harsh decree. Too much chesed (overflowing lovingkindness) might lead to emotional floodwaters. But when all of God's qualities are in right balance -- when all of the colors of the rainbow are present -- then the earth can know peace.

The rainbow reminds me of the need to accept and integrate disparate parts of ourselves: our lovingkindness and our ability to draw boundaries, our balance, our ability to endure. We who are made in God's image also contain all of these colors of self and soul, and we need all of them.

Sometimes we see our spectrum of inner qualities most clearly through the prism of tears. Whether we weep in sorrow or in gladness, times of deep emotion offer opportunities to see ourselves more clearly. When tempestuous internal weather meets the light of one's neshama, the light of one's soul, that light can be refracted through tears -- just as literal sunlight is refracted through rain.

What kind of rainbow is revealed in us when the light of the neshama is refracted through tears? What does it feel like to become aware of those internal colors, to accept our own range of emotion and spirit so that the rainbow of our whole selves can stretch resplendent across our inner skies?

This is the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for parashat Noach. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

October 16, 2015

Glimpses of Beyond Walls

The Kenyon Institute has released a beautiful video about Beyond Walls, the spiritual writing program for clergy in which I was blessed to teach this past summer.

If you can't see the embedded video, here's a link to the video on YouTube.

Watching the video reminds me of what a lovely experience it was to teach there. If you're curious about Beyond Walls, the video will give you a good sense for what the program was like.

I won't be teaching at Beyond Walls in summer 2016 -- it's at the same time as the 2016 ALEPH Kallah -- but I'm planning to return in 2017, for sure.

October 14, 2015

The specialness of the ordinary

Those who pay close attention to the Jewish calendar, or who pay close attention to the night sky, may have noticed that the moon has started waxing again -- which means we've entered a new lunar month. After the intense constancy of the month of Tishri -- which contains Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Hoshana Rabbah, Shemini Atzeret, and Simchat Torah -- comes the month which contains no holidays other than Shabbat, that holiest day of the year which recurs every seventh day.

Some call this lunar month חשון / Cheshvan. Some call it by the name מרחשון / Marcheshvan, and interpret that name as "bitter Cheshvan" -- mar means bitter -- because there are no holidays this month besides Shabbat. Though Rabba Emily Aviva Kapor-Mater noted recently that "The name of the month derives from the Akkadian waraḥ-šamnu meaning 'eighth month' (think cognate to ירח שמיני). Remember, last month Tishri, though first, is actually seventh, and so Marḥeshvan is eighth."

(What does she mean about Tishri being both first and seventh? Well, it depends on which new year you're counting from. The Talmud lists four different new years. If the new year is at Pesach, then Tishri is the seventh month; if the new year is at Rosh Hashanah, it's the first month. Her point is that Marcheshvan can't mean "bitter Cheshvan" because its etymology clearly implies "eighth month." Still, far be it from me to object to a poetic interpretation, as long as we know that it's poetry.)

Still others call this month רמחשון / Ram-cheshvan, "High Cheshvan," suggesting that this month is high and holy precisely because its holiness is hidden, or suggesting that this month's true holiness will make itself known in a time to come. (I believe that teaching originally came from Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach z"l.) I like the inversion. The fact that this month has no overt holidays doesn't make it lesser-than. Quite the opposite, in fact. What appears to be most ordinary is in fact most special.

It makes me think of one of my favorite teachings from the Slonimer rebbe about the holiness of the white space. (This is a Shemini Atzeret teaching; I've posted about it here before.) He talks about how the letters of the Torah are holy, and so is the parchment on which they are written. The black fire is holy, and so is the white fire within which it is contained. The days of our festivals are holy -- and so is the context of chol, of ordinary time, within which our days of kedusha, holiness, are cradled.

I like the idea that this month's specialness is hidden. Like a secret language which only those who care will learn to speak. Like secret music which most people don't bother to make the effort to hear. Who knows what opportunities for connection might lurk beneath this month's overtly ordinary exterior? No festivals, no shindigs, no fancy observances -- just a month during which we can reconnect ourselves with the rhythms of weekday and Shabbat, and rediscover the holy opportunities of ordinary time.

Related:

The year as spiritual practice, 2009

The empty month, 2010

Seasonal, 2013

Cheshvan, 2014

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers