Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 103

July 13, 2016

A teaching from Joel Segel on equalizers of heart and soul

On the first day of Big Sky Judaism: The Everyday Thought of Reb Zalman z"l, Joel Segel took us into an imagined conversation with Reb Zalman about rationalism:

On the first day of Big Sky Judaism: The Everyday Thought of Reb Zalman z"l, Joel Segel took us into an imagined conversation with Reb Zalman about rationalism:

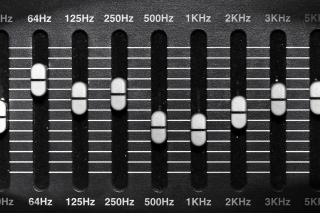

"I hear where you're coming from. I understand the appeal of the intellectual. And: you're a musician, so you know what an equalizer is, yes? Imagine that at the bottom of the equalizer, instead of Hz and kHz are written labels that read intellectual, emotional, physical, spiritual.

I'm hearing that your intellectual faders are up, and all the rest of them are down. So try an experiment. Pull up the faders in heart space. What happens in you when you pick up the heart fader? Maybe what happens is that you experience yourself feeling an internal voice chorusing 'Ribbono Shel Olam thank You thank You thank You.' Push down the intellectual fader and pull up the emotional one and see what arises in you."

The four equalizers map, of course, to the Four Worlds about which we so often speak in Jewish Renewal: assiyah (action / physicality), yetzirah (emotions / heart), briyah (intellect / contemplation), and atzilut (essence / spirit.) Everything is always happening in all four of these realms at once, though many of us feel more comfortable in one of these worlds than the others.

At lunch after class I shared this image with a friend who knows something about recording music, and she pointed out that the name "equalizer" points the layperson in the wrong direction. The goal isn't to make all of the faders "equal." For one track one might want more treble; for another track, more bass. Just so, the internal equalizers about which Reb Joel was teaching us. Maybe when I'm hiking in the Colorado hills my physical fader is high, since I'm unusually aware of my body and my surroundings -- whereas when I'm davening, my emotional and spiritual faders might be at peak.

Different moments in the day, different days in the week, require different balances. The goal isn't to perfectly equalize our experience of the four worlds -- or at least I don't think it is. The goal is to cultivate awareness of which world(s) I'm living in, and to learn the practice of adjusting my own psycho-spiritual faders. Just as different instruments speak different languages but they're all needed in the orchestra, just so different parts of ourselves need to be allowed to speak as we inhabit the four worlds in different ways.

July 11, 2016

Four glimpses of the pre-Kallah Shabbat

Mincha in the mountains.

1.

Unlike at last Kallah (when we were on a lake -- an easy natural mikvah), no formal mikvah experiences are scheduled for smicha week. But on Friday afternoon of my first week here, two friends and I decide to create our own. We make our way to the campus rec center, where there is a huge pool with a beach-like slope at one end, and a large and spacious hot tub, too. We opt first for the hot tub, and -- immersed in its foaming waters up to our necks -- we talk about what we need to release from our lives in general and from the week now ending in particular. And then we immerse. It's not a kosher mikvah, of course -- it's a swimming pool, with no source of living waters; for that matter, we're wearing swimsuits -- but on a spiritual level when I emerge from the waters after my final immersion I feel lighter. More radiant. More ready to welcome Shabbat.

2.

As I make my way back to my dorm after the festive meal that followed Kabbalat Shabbat, I am drawn to the trio of guitarists sitting on one of the semicircles of big stones on the lawn outside the building. (So are a few dozen other people.) I settle happily on one of the big rocks that serves as a bench, and as they play and sing, the assembled group sings with them. They play (and we sing) the birkat hamazon (grace after meals), prayers, folk songs, new melodies, old melodies. In between singing harmony with my friends, I have conversations with current and prospective ALEPH students, with faculty, with other musmachim (alumni / ordinands). We sing and sing and sing. And sing some more. Between the singing and the Shabbat wine, by the time I stagger up to my room (well after midnight, which means it's well after my bedtime!) I am exhausted... but grateful.

3.

On the campus where we're staying the grounds are pretty flat. But off to one side there are mountains, and I don't want to spend two weeks at the cusp of the Rockies and never actually see the mountains themselves! So on Shabbat afternoon two friends and I head to Horsetooth Mountain Park, and we walk up into the hills. It's a hot day, and we're at altitude; I huff and puff more than I would prefer. But the hills around us are extraordinarily beautiful. My spirits are lifted by the grasses and piñon pines and wildflowers, by the clouds scudding across the blue sky, by the sound of wind in the grasses. We sing bits of the Shabbat afternoon service to the special nusach (melodic system) used only at that time on that day. "Mincha" means offering or gift. In that moment, singing bits of the ashrei on a trail in the hills in the sunshine, everything feels like a gift.

4.

After evening davenen we make our way outside for havdalah. We form a huge circle, arms around each other. Fragrant teabags are passed out for our b'samim, the spices we will bless to prevent ourselves from fainting as the second Shabbat soul departs. Havdalah candles are lit. We sing the words I love so very dearly: hineh El yeshuati, evtach v'lo efchad... (This is the God of my redemption; I trust, I am not afraid...) We sing the blessings sanctifying the One Who makes divisions between Shabbat and the week. When the candles are extinguished a few people sing to Elijah the prophet in Ladino, and then we sing Eliahu HaNavi and Miriam HaNeviah in Hebrew, and then people start dancing as the musicians keep on playing. La-yehudim haita ora -- a prayer for light and joy and honor for us in the week now beginning. We sing, and we dance, and the week begins.

Related: Six jewels from Clergy Camp.

Ready for the 2016 ALEPH Kallah!

The 2016 ALEPH Kallah begins later today, and I can't wait.

This week-long wonderland of learning, davenen, community, and togetherness has been in the works for a long time. Behind the scenes at ALEPH we've been working hard on this for a solid year. I can't offer enough praise for Tamy Jacobs, our Kallah coordinator; or for Judith Dack, our Kallah Chair; or for the countless teachers, rabbis, artists, planners, and volunteers who have been working overtime to bring this week into being.

And now it's finally here. I've been at Colorado State University in Fort Collins for a week already (enjoying Clergy Camp), and almost all of us who were here last week are staying for Kallah. We'll be joined by hundreds of others today; by tonight, there will be around 500 people gathered for our celebratory welcome and opening ceremony. (One of those people joining us today is my six year old, who will be attending the Kids' Kallah. I am especially excited about his arrival!)

I'm teaching a class this week, and also taking a class. With two other ALEPH Board members, my co-chair Rabbi David and my friend Rabbi Evan Krame, I'm co-leading Thursday morning davenen. Aside from those things, I don't know exactly what my week will hold. But I expect that the week will feature togetherness, and learning, and high-spirited davenen, and countless conversations, and a variety of wonders I can't yet name.

For those who are traveling to Kallah today: travel safely -- can't wait to see you here! For those who aren't joining us, I'll do my best to post a few times over the course of the week to give you glimpses of what you're missing... and I hope you'll be able to join us in two years' time for the next ALEPH Kallah!

July 7, 2016

Six jewels from Clergy Camp

Thursday morning davenen. A rainbow of tallitot (prayer shawls); a rainbow of neshamot (souls).

1.

On Monday morning, the Fourth of July, we daven in semicircles of chairs beneath the trees. It feels so good to be sitting beside some of my dearest beloveds and beaming at others across the semicircle.

And then when we get to the blessing for redemption (emet v'yatziv, for those who know the liturgy) the leaders start singing "Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of Hashem," and a ripple of laughter runs around the space. We sing the whole prayer to the melody of The Battle Hymn of the Republic, with gusto and multi-part harmony. Mi chamocha ba-eilim Adonai -- the words scan perfectly, and there is something wonderful about setting our song of redemption to this old American hymn. It feels glorious -- both the playful creativity of the melodic choice (the kind of thing Reb Zalman z"l used to love) and the heart with which everyone sings the words.

Davening with heart and creativity and with my loved ones always feels like coming home.

2.

On the first morning of class with Rabbi Jeff Fox we study Talmud, Tosafot, Judith Plaskow, Tamar Ross, and Rambam, all of which inform our conversation about geirut (conversion) and the unfolding of Jewish tradition. I can feel synapses sparking to life that haven't been lit up in ages. The text study is enlivening, and the conversations that it engenders are even more so.

We talk about Ruth and Ezra as opposite Biblical paradigms for how to relate to conversion. We talk about how Rashi sees the Exodus to Sinai journey as parallel to, and as a kind of, conversion. We talk about Jewishness as spiritual practice and Jewishness as peoplehood and what happens when we try to separate those two. We talk about the implication of seeing the Sinai moment as the paradigmatic experience of Jewishness if that moment occurred only for the men.

I wish I could send a message back in time to my collegiate religion major self. Could I have imagined then that someday this would be my life: sitting around a table with wise colleagues who are at least as passionate about Judaism as I am, grappling with tradition, asking hard questions and taking joy in the wrestle?

3.

Each of the three daily services are led by groups of students. I remember being a student and working with my friends to plan and co-lead services for smicha students' week -- trying to find the right balance between tradition and innovation, stretching our skills, sometimes falling on our faces, finding our wings as davenen leaders and learning to soar.

One morning the prayer leaders take lines from Lin-Manuel Miranda's sonnet and use them as a call-and-response prelude to the bar'chu, the call to prayer. When the whole room choruses "Love is love is love is love is love" I get goosebumps.

4.

Around the room, Rev. Bill Kondrath has posted signs with drawings of different emotional states, labeled with single words: "scared," "joyful," "sad," "mad," "powerful," "peaceful." He invites us first to stand beneath the sign depicting the emotional state that felt most safe to us in childhood. Then to stand beneath the sign depicting the emotional state we felt least able to express in childhood. And then to stand beneath the sign depicting the emotion we habitually substitute for the one we didn't feel safe expressing.

In the conversation that ensues, one of my classmates mentions Reb Zalman's teachings about the need for rabbis to serve as geologists of the soul. This is maybe especially true for those of us who serve also as spiritual directors: it's our task to help those whom we serve to uncover the gems buried in the strata of their own hearts.

Some of what we find inside is joyful, and some of what we find can feel like land mines. But the only way to defuse the land mines is to find them and gently dismantle them, and the only way to uplift the gems is to unearth them and polish them and let them shine.

5.

Thursday morning. We are once again davening outdoors, this time in a little courtyard. It's the second day of Rosh Chodesh (the new moon -- the beginning of the lunar month of Tamuz). We sing the blessing for Hallel in a lusty call-and-response. And then my friend Hazzan Dave Abramowitz, who goes sometimes by the nickname "Tall" (for reasons obvious to anyone who knows him), belts out chasdo, ki l'olam chasdo to the tune of "Day-O." I've sung Psalm 118 to this melody before, but with his big baritone voice leading us, the singing is extra-delicious.

A little bit later in Hallel, when we sing Zeh hayom asah Adonai, "This is the day that God has made: let us rejoice and be glad in it!" I think: yes. Yes, it is. This very day is a day created for us to rejoice in it. Every day is a day created for us to rejoice in it. How fortunate I feel to be in a place, this week, where it is so easy to access that awareness.

6.

Getting to study conversion all week with the rav who authored this teshuvah on the presence of a male beit din at the immersion of a female convert [pdf] is a mechaieh -- it's life-giving. The conversations are fantastic and thought-provoking. Over the course of the week we study Yevamot. We study rabbinic teshuvot (responsa). We learn the strange story of Warder Cresson. We study the stories of the converts of Hillel and Shammai, and the story of the student of Rabbi Chiyya.

We talk about the physical process of conversion, and we talk about the psycho-spiritual process of conversion. We talk about what it means that there are people who won't accept certain conversions, and about the implications for someone who might convert under one set of assumptions and then shift to a different community of practice. We talk about motives for conversion: how much do motives matter? We talk about: what does it mean to come beneath the wings of Shechinah? What does it mean to accept the yoke of the mitzvot?

At the end of our last class we go around the room and each person mentions something in our learning that especially moved us. We close with a kaddish d'rabbanan, the special kaddish recited at the end of study, in gratitude to and in honor of our teacher. It has been an extraordinary week of learning. I am so grateful.

July 3, 2016

Off to Clergy Camp!

I'm on my way today back to Colorado for two weeks of ALEPH programming. The ALEPH Kallah begins on July 11, and of course I'll be there for that -- wouldn't miss it for the world. But I'm going to be there this week, too.

I'm on my way today back to Colorado for two weeks of ALEPH programming. The ALEPH Kallah begins on July 11, and of course I'll be there for that -- wouldn't miss it for the world. But I'm going to be there this week, too.

During my years of rabbinic school, I always went to another week of ALEPH learning before the Kallah -- what we called "smicha students' week" (or "smicha week" for short), a week-long learning intensive with the ALEPH Ordination Program community of students and faculty.

We would daven together three times a day, learn together all day and all evening, and generally enjoy the pleasure of steeping in one another's company and in our studies. The classes we took during those intensive weeks would continue via teleconference calls (or, by the time I finished the program, webconference video calls) for months thereafter.

Last time I did that was summer of 2010. (I wrote about it here: My last smicha students' week. That's where I wrote the poem that begins "Don't chew on your mama's tefillin...") As that poem makes clear, I had an infant at the time, and navigating his needs while immersing in study and community made that a week not quite like any other.

The following January I was ordained, and since then, I haven't attended smicha students' week -- it's not for me anymore. I've felt some sadness about that. I miss the hevreschaft (community of learners) and the spirited daily davenen. But it's a natural consequence of finishing rabbinic school, so I accepted it... until now.

This year ALEPH is piloting a new program for ordained clergy, which we're calling Clergy Camp. Those of us who are ordained and practicing in the field are invited back during smicha students' week for our own dedicated learning track. While the students are doing their learning, we'll be doing our continuing education. We'll get to share meals and davenen with the ordination program community. I anticipate that it will feature much of the joy I used to take in smicha students' week -- without the stress of being a graduate student!

During the mornings I'll be studying geirut, conversion, with Rabbi Jeff Fox, the rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Maharat, the groundbreaking Orthodox seminary ordaining women to serve as clergy. During the afternoons there will be a skills practicum taught by Reverend Dr. Bill Kondrath, Director of Theological Field Education at Episcopal Divinity School. During the evenings we'll be integrating our learning via group hashpa'ah (spiritual direction.) It promises to be a rich and full week. I'm incredibly excited about it. To those whom I'll be seeing at Clergy Camp, and those whom I'll be seeing at Kallah next week: travel safely!

July 1, 2016

On the cusp of promise

In this week's Torah portion, Shlakh, ten scouts are sent to glimpse the land of promise. What they see there terrifies them. The grapes are so big that two men are required to carry a single bundle. They return to the community and report that entering this land is simply not possible: "the inhabitants are giants, and we must have looked like grasshoppers to them!"

In this week's Torah portion, Shlakh, ten scouts are sent to glimpse the land of promise. What they see there terrifies them. The grapes are so big that two men are required to carry a single bundle. They return to the community and report that entering this land is simply not possible: "the inhabitants are giants, and we must have looked like grasshoppers to them!"

They spread their fear to the children of Israel, and God -- incensed that after all the miracles they've experienced, the children of Israel do not trust -- declares that this generation will wander in the wilderness until they die. Their children will enter the land, but they will not. They are too caught in their own fear.

I suspect we all know what it's like to glimpse a land of promise and then to shy away. The work it would take to get there is too vast. The personal changes required are too difficult. Maybe, like the children of Israel who came out of Mitzrayim, "the Narrow Place," we are too shaped by our familiar constraints.

Once limits become habitual, they become invisible: we don't even notice them anymore. We learn to live within a small space. We train ourselves not to grow beyond the box, because outside the box is scary. Outside the box the grapes are as big as beach balls. Outside the box we are afraid we will be as insignificant as grasshoppers.

Spiritual life calls us to recognize our own fear. To notice what buttons are pushed when we think about expanding beyond whatever our limits have been. To breathe into the paralyzing fear of failure, of smallness, of taking on something we won't be able to handle. And spiritual life calls us to breathe through that fear, and to step into the unknown.

When we sing "Mi Chamocha," the song at the sea, I often invite us to remember a time in our lives when we've felt like the children of Israel trapped between the Egyptian army and the sea. A time when it felt as though there was no way through. And I invite us to recognize that no matter what seas we're facing, we don't have to cross them alone.

We stand at the shore of the sea no less than our ancient ancestors did. And no less than our ancient ancestors, we are always at the cusp of the land of promise. A place of expansiveness, a place of nourishment and sweetness, a place of divine flow.

We will have to acknowledge our fears in order to get there. We may have to accept our own feelings of smallness. But we can choose to trust even though we are afraid. And when we do, the One Who accompanies us in all of our changes will accompany us into infinite possibility. Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so.

This is the short d'var Torah I offered this evening at Kabbalat Shabbat services at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

June 28, 2016

On "micro-spirituality" at The Wisdom Daily

My latest essay for The Wisdom Daily is online. It's on what one might call "spirituality on the run" -- the challenge of maintaining spiritual practice or spiritual life at the frantic pace (and frequent multitasking) of ordinary life. Here's a taste:

My latest essay for The Wisdom Daily is online. It's on what one might call "spirituality on the run" -- the challenge of maintaining spiritual practice or spiritual life at the frantic pace (and frequent multitasking) of ordinary life. Here's a taste:

The laundry, the bills, the phone calls to return — the logistics to organize, the committee meetings, the errands to run — these are things that appear to have no limit. Who has time for spiritual practice when life looks like this? Of course, it’s because life looks like this that we need spiritual practice most.

I love the deep dives I can take on vacation or retreat, when I have the profound luxury of being able to set “normal life” and its pressures aside. But these are rare, tiny islands in the sea of stressors and obligations. How can I maintain enough of a spiritual practice in the midst of life’s chaos to keep me stable, sane, on an even keel, even joyful?

One answer is to rejigger what I think “spiritual practice” means...

Read the whole thing: Using "Micro-Spirituality" to Center Our Daily Lives.

June 25, 2016

I trust you: I am not afraid

You watch over my changes.

I trust you: I am not afraid.

I find strength in your song.

I become more myself.

Together we draw water in joy

from the living well.

We draw forth the changes

with which you bless me.

I'm not alone: you are with me,

no matter what name I call you.

I'm the luckiest woman in the world

because I have you.

Even when grief rends my throat

I'm not alone: you are there, and

my changes are there

waiting for me.

This poem arises out of the opening prayer of havdalah, "הִנֵּה אֵל יְשׁוּעָתִי / Hineh el yeshuati." (You can hear all of the prayers of havdalah beautifully sung here at the Havdalah page at B'nai Jeshurun -- there are also good translations and transliterations there, if that's helpful to you.) This is not a translation by any stretch -- but those who know the traditional words will hopefully hear their resonances in these lines.

Shavua tov -- may the coming week bring blessings to all.

June 23, 2016

Rabbi Jack Riemer on 70 faces

A while back I received a note from Rabbi Jack Riemer, author of one of my favorite revisionings of Unetaneh Tokef, and co-author with Sylvan Kamens of We Remember Them, which I use at every funeral. He had written a new review of 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia Publishing, 2011), and his review was published in the South Florida Jewish Journal.

A while back I received a note from Rabbi Jack Riemer, author of one of my favorite revisionings of Unetaneh Tokef, and co-author with Sylvan Kamens of We Remember Them, which I use at every funeral. He had written a new review of 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia Publishing, 2011), and his review was published in the South Florida Jewish Journal.

It's always a gift to receive a review of a book some years after its publication -- and especially so when the author of the review is someone whose work I so respect. Thank you, Rabbi Riemer! And thank you also for giving me permission to reprint the review in full on this blog.

70 faces: Torah poems

by Rachel Barenblat,

Phoenicia Publishing,

Montreal, Canada, 2015, 81 pages

Reviewed by Jack Riemer

We have had women rabbis for more than a generation now. We have a generation of young people who have never known it any other way. But if we stand back, we can see at least three contributions that women rabbis have made to our spiritual lives.

One is that women rabbis have given a whole new emphasis to the spiritual side of healing. We knew that rabbis were supposed to visit the sick, but women rabbis have given us a whole new perspective into the spiritual dimension of healing. A second contribution they have made is their emphasis on prayer as a matter of the inner life, which was always there, but which was and is often neglected. And a third contribution that women rabbis have made is the creation of poems that see God in a whole series of bold new images that we were not accustomed to seeing before.

This collection of poems by Rachel Barenblat, one for each sedra of the year, is a good example. No male rabbi would have written a poem that says:

Postpartum depression caused the Flood.

God was elated when creation was born

every facet unfolding a reflection

light and darkness, as above so below

But God ached all over, God felt hollow

God walked in the empty garden disconsolate

already nothing was the way God planned it

and Abel's blood cried out from the soil

Could the whole project be a wash?

In God's heart, regret bloomed hot

and a tempest of sorrow rained down on earth

Still, some simple sweetness in us

roused divine compassion like milk

found favor in God's tired eyes.

It is a tender image of the creation that we have in this poem, is it not?

God the mother gives birth with elation, and then God goes through the feeling of emptiness that follows after every birth, and the sense of disappointment at the way things turn out that follows some births, and then, when regret blooms hot, and God is tempted to wash the world away, a compassion for us, something like the milk that every mother feels inside-- that needs to pour out for her own sake as well as for her child’s sake, comes out and saves us.

Let me share just one more poem from this collection. In order to read it, you must put aside your politics, at least for a moment. You must forget the fact that self-defense is a necessity in Israel and that searching those who would go through its checkpoints is an essential task, a matter of life and death for Israel. Try to forget for just a moment, if you can, that those who come to the checkpoints may, and often are carrying hidden weapons. Try to forget for a moment, if you can, that America does the very same thing that Israel does, before it lets anyone board a plane. Try to forget all these undeniable truths for just a moment, and try to focus if you can, as this poem does, on the damage that doing these searches does to the minds and the souls of the eighteen year old Israeli soldiers who must do these searches all day, every day. And then, after you have winced at the painful truth expressed in this poem, you may go back and reaffirm all these facts and you may understand that these searches are absolutely necessary and yet you can understand that it is sad that this is so.

The poem is called ‘Downside” and it is based on the warning at the end of the book of Bamidbar that you must guard yourselves against the people who live in the land that you are about to take possession of, or else they will harass you.

Here's the part

God apparently didn't say

at least not aloud

where anyone could hear:

dispossessing anyone

not as easy as it sounds

and tends to have

occasional side effects

feelings of guilt

among the tender-hearted

and a certain hardening

of those who do battle

refugee camps

persisting for generations

breeding bitter fury

which tends to explode

and don't forget

the damage done

to your chelek Elohim,

the eternal spark in you

which dims a little bit

with each interrogation

each humiliation

of another face of God.

You have to wince for a moment when you read this poem, and then you can shake it off if you want to, and you can go back to the practical world, the world in which searches may be ugly but in which they are necessary. But this poem will go with you, and on occasion it will make you wish that it were not so.

Read the rest of the poems in this collection and they will help you see the portion of the week in a new light. Some will make you smile; some will make you angry, but all of them will make you see the words of the Torah in a fresh and different light, and that is what Torah study is meant to do for us each year.

70 faces is available for purchase on the Phoenicia Publishing website and also at Amazon, though the publisher and I both make a little bit more if you buy the book via the press.

June 17, 2016

Joy amidst mourning

All week I've been thinking about what I might say here in shul this morning. Mere commentary on this week's Torah portion feels insufficient. How can I talk about the rituals of the nazir, one who makes promises to God -- or the ritual of the sotah, designed to banish a husband's jealousy -- or even the priestly blessing that we just read together -- when LGBTQ members of our community are grieving so deeply? And yet faced with the enormity of the tragedy at Pulse last weekend, my words fail me.

Into this moment of grief comes an expression of great joy. Just moments ago we welcomed a beautiful little girl into the covenant and into our community. What words of meaning can I offer to her two mothers now?

I can say: you belong here. In this community those of us who are straight aspire to be thoughtful and sensitive allies, so that those of us who are queer can feel safe expressing all of who we are.

I can say: tell us what you need. Tell us where we are falling down on the job of making this a safe and celebratory and welcoming home for you, and we will try to do better. I can say: your child will always have a home here, no matter how her gender expression manifests or who she loves.

And I can say: all of us here commit ourselves to building a world in which hate crimes are unimaginable. A world in which no one could feel hatred toward another human being because of that person's race or gender expression or sexual orientation or religion. Can you imagine what it would feel like to live in that world?

Can you imagine a world in which the tools of massacre no longer exist? In the words of the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai: "Don't stop after beating the swords into plowshares, don't stop! Go on beating and make musical instruments out of them. Whoever wants to make war again will have to turn them back into plowshares first."

Our tradition has a name for this imagined world in which hatred has vanished like a wisp of smoke: moshiachtzeit, a world redeemed. I don't know whether we will ever get there. But I know that we can't stop trying.

And there is a very old Jewish teaching that each new baby contains all the promise of moshiachtzeit, all the promise of a world redeemed. Maybe this baby will help to bring about the healing of the world for which we so deeply yearn.

May we rise to the occasion of being her community. May we support her and her mothers. May we take action to lift them up and to keep them safe. And may we work toward a world redeemed in which all of our differences are celebrated and sanctified as reflections of the Holy One.

And let us say, together: amen.

These are the words I spoke from the bimah yesterday morning at my shul. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers