Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 102

August 7, 2016

Wake to you

I want to wake to you. When my alarm pulls me

(a silvered trout, struggling, from sleep's stream)

you remind me I breathe air, can thrive. Your song

calls forth my own. I'm a tuning fork, vibrating.

When my walls crumble and fall, you show me what stays.

Point out that shrinking myself won't keep me safe.

You take delight in my strength, urge me: be more.

You don't want artifice. You exult when I shine.

When I relinquish control at the end of the day

and slip into sleep you keep me safe and seen.

In dreams I give you the keys to my secret places

but you don't need them: my door is open to you.

You know my true name. You know my tender heart,

the path into my garden where roses bloom.

This is another poem in my ongoing Texts to the Holy series.

I had fun with meter in this one; it's not exactly in iambic pentameter (though some lines are), but on the whole the lines have five stresses apiece, which is something that emerged in an early draft and then I chose to play with. Also, though the original draft was longer, it now has the same number of lines as a sonnet. Though right now I'm keeping it in couplets, I'm considering whether I prefer the visual prosody of four quatrains and a couplet instead.

I'm a tuning fork, vibrating. I love the fact of sympathetic resonance, both as a metaphor and as a reality.

When the walls crumble, you show me what stays. See my recent post Entering Av.

[T]he path into my garden hints at the beginning of chapter 5 of Song of Songs. (By the way: Reb Zalman z"l wrote a beautiful melodic setting of those verses, which you can hear in this video from Nevei Kodesh in Boulder, a congregation I was blessed to visit this past spring.)

[W]here roses bloom. The Zohar is rife with images of roses and rose gardens, and associates them with Shechinah, the immanent, indwelling, feminine Presence of God.

On healthy humility as Tisha b'Av approaches

As Tisha b'Av approaches, I've been thinking about ענוה / anavah, humility. About this quality, my friend and colleague Rabbi Barry Block writes:

As Tisha b'Av approaches, I've been thinking about ענוה / anavah, humility. About this quality, my friend and colleague Rabbi Barry Block writes:

The Mussar Institute’s recommended daily affirmation for ענוה (anavah – humility) is, “No more than my place, no less than my space.” The second half of the phrase suggests that one who is “too humble” isn’t humble at all. Now that’s a חידוש (chiddush, a new insight), particularly important for rabbis.

(That's from his essay Mussar for rabbis: humility.)

Humility and Tisha b'Av are often linked because of a story about how excess humility led to the destruction of the second Temple. (Rabbi Barry cites it in his essay.) In a nutshell, it goes like this: in 70 CE, the Romans -- in partnership with a Jewish collaborator -- sent to the priests an animal they had intentionally blemished, making it ritually unfit for sacrifice.

This put the priests in an impossible bind: either they could reject the Romans' sacrifice (thereby incurring Roman wrath), or they could sacrifice the blemished animal (thereby going against God), or they could kill the collaborator who had brought them the animal (thereby unjustly taking a life, and giving the impression that the punishment for presenting an unfit animal for sacrifice was the death penalty.)

They asked Rabbi Zecharia ben Avkulus to decide which of these bad choices was least bad, and he declined to rule. He was paralyzed, and therefore he chose inaction. (He may not have seen it as a choice, but it was -- opting for inaction is itself an action.) His people needed him to occupy the space of leadership and responsibility, to make the call about how to proceed, and he didn't, or he couldn't. The choice before him was a terrible one, but in declining to choose, he made the situation far worse. His reluctance to occupy the space of leadership led to the destruction of the Temple, our place of connection with God.

Lately I've been wearing a wristband emblazoned with words from Rabbi Simcha Bunim. The story goes that he carried two slips of paper in his pockets at all times, and on those papers were the words בשבילי נברא האולם (for my sake was the world created) and ואנכי עפר ואפר (I am but dust and ashes). Each of these is a necessary reminder, and each serves as a corrective to the other. When I'm feeling small or low or insignificant, I need to be reminded that all of creation came into being precisely in order that I might exist here and now. And when I'm feeling haughty or prideful, I need to be reminded that I am temporary and will die.

When I glance down, I never know which of the two phrases I'm going to see. But of the two phrases, I think the one I most often need to see is "For my sake was the world created." Many women struggle with the unconscious internalized sense that we are "supposed" to be quiet, or deferential, or to pursue peace with others even when the peacemaking comes at the expense of our own voice, our own truth, our own strength. (Men struggle with this too, of course, but this tends to systemically afflict women. See 9 non-threatening leadership strategies for women -- behind the humor, the ugly truths are all too real.)

Holding oneself back in order to please others (or in order to not risk offending others, which is a variation on the same theme) isn't humility. It's taking up (in R' Alan Morinis' words) "less than my space," and that's not a character strength, it's a character flaw. That's the sin of R' Zecharia ben Avkulus, which our sages teach led to the destruction of the place our people held most dear. Keeping silent in the face of injustice or untruth isn't a virtue, and it's often driven by the kind of fear I spoke about from the bimah on Shabbat. We diminish ourselves when we let fear rule us, and self-diminishing isn't humility and isn't healthy.

As Tisha b'Av approaches, what would it look like to relinquish the false humility of excess silence? To practice making difficult choices, and speaking difficult truths, and taking responsibility for one's power and one's ability to create change, even when so doing feels risky because of how others might respond? To take up exactly as much space as God intends each of us to inhabit -- knowing that we are dust and ashes, and also that we are reflections of the Infinite, precious and holy, entitled to enough room to stand in, entitled to enough air to breathe, obligated by virtue of our agency to work toward building a better world?

August 5, 2016

Entering Av

This isn't so much a "d'var Torah" as a "d'var calendar" -- the text I'm exploring this morning is the unfolding of our calendrical year.

On Friday, just before Shabbat, we entered into the lunar month of Av. Av contains the low point on our communal calendar: Tisha b'Av. Tisha b'Av is the day when we remember the destruction of the first Temple by Babylon in 586 BCE, the destruction of the second Temple by Rome in 70 CE, and countless other tragedies that have happened at this season in other years, from the beginning of the first Crusade, to the expulsion from the Warsaw Ghetto and the mass extermination that followed.

Tisha b'Av is a day for confronting brokenness. The brokenness of the world. The brokenness of our hearts. And yet tradition teaches that on the afternoon of Tisha b'Av, moshiach will be born. The beginnings of our redemption arise from this very darkest of places. It's a little bit like the Greek myth of Pandora who opened the box containing war and destruction and famine and all manner of awful things -- and at the bottom of the box, found hope. A tiny spark of light to counter the darkness.

It's the height of our beautiful Berkshire summer. Why would we choose, as we move into Av, to delve into grief? Because if we don't let ourselves feel what hurts, we can't move beyond it. If we don't let ourselves acknowledge what's broken, we can't mend. If we don't let ourselves acknowledge what feels damaged, we can't begin to repair it. Brokenness is part of the human condition, and the only way to transcend it is to let ourselves feel it fully. Feeling what hurts is the first step toward healing the hurt we feel.

According to the Mishna, on Tisha b'Av we mourn not only that long list of historical calamities, but also a psychospiritual one: the time when the scouts went into the Promised Land, and became afraid of what they saw, and returned to the children of Israel and said "we can't go there, those people are giants, we must have looked to them like grasshoppers." Av is a time for remembering how we diminish ourselves when we let go of faith for a better future and let our fear rule us instead.

Why would we want to look at the times when we've been afraid? Why would we want to examine our own complicity in the cycles of brokenness that are a part of every human life -- how we keep bringing ourselves, over and over, back to the same issues, the same fears, the same hurts? Because in that examining, we strengthen our power to make different choices. We don't have to repeat the mistake the scouts made. We don't have to repeat our own mistakes. We can make teshuvah -- we can turn.

Rabbi Alan Lew writes,

Tisha b'Av is the moment of turning, the moment when we turn away from denial and begin to face exile and alienation as they manifest themselves in our own lives -- in our alienation and estrangement from God, in our alienation from ourselves and from others.

This new lunar month invites us to recognize that our constructs -- the narratives we've inherited or built to tell us who we are -- are just that: constructed. And like everything else in this world of entropy, they fall apart. When our constructs are shattered, we feel shattered, too. But Tisha b'Av comes to teach us that even when the walls crumble, even when the Temple is destroyed, even when our constructs shatter and we feel adrift, something more lasting than all of these persists in us.

You can call that something "God." You can call that something "Love." You can call that something "Transformation."

Av is our month of greatest sorrow -- and in that greatest sorrow, we find an opening to joy. In facing what's falling down, we find a way for our spirits to rise up. In facing our fear and our complicity in succumbing to that fear, we find an opening into a future of promise. In facing our feelings of helplessness, we find strength. In facing the darkness, we find light. Kein yehi ratzon.

These are the remarks I offered at my shul yesterday morning (cross-posted to my congregational blog.)

You might also find useful this set of resources for Tisha b'Av 5776 on Kol ALEPH, the blog of ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal.

August 1, 2016

Diving into Jewish-Muslim dialogue again

In August of 2009, I went on a retreat for emerging Jewish and Muslim religious leaders organized by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. In June of 2014, I returned to that retreat as an alumna facilitator. This week I'll be spending a few days at a retreat center a few hours from here, once again serving as alumna facilitator for an extraordinary group of Muslim and Jewish religious leaders. I'm really excited about getting the opportunity to do this work again, and about further building and strengthening connections between our two religious communities.

In August of 2009, I went on a retreat for emerging Jewish and Muslim religious leaders organized by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. In June of 2014, I returned to that retreat as an alumna facilitator. This week I'll be spending a few days at a retreat center a few hours from here, once again serving as alumna facilitator for an extraordinary group of Muslim and Jewish religious leaders. I'm really excited about getting the opportunity to do this work again, and about further building and strengthening connections between our two religious communities.

This year's retreat is co-presented by RRC and ISNA. I remember that there was conversation, at the 2014 retreat, about the challenges for Muslim religious leaders of signing up for a program presented solely by a Jewish institution. I can imagine feeling the same way were our positions reversed -- how would people in my community react if I signed up for a leadership program offered by a Muslim seminary? -- and I'm happy that this time the retreat is co-presented by institutions from both of our communities. I give kavod (honor) to RRC and ISNA for their joint willingness to make this retreat happen -- and also to the Henry Luce Foundation and the Legacy Fund for their fiscal support of this holy work.

As on previous retreats, we'll spend some time engaging in text study as a spiritual practice, exploring the texts that are sacred to each of our traditions. We'll do some learning and sharing about each of our traditions. We'll break down some of the stereotypes each group can't help unconsciously holding about the other. (In my experience part of what's interesting is always discovering the unthinking stereotypes we carry within our own communities, too -- there's a lot of diversity, and also a lot of misunderstanding, among and between different branches of Judaism as well.) We'll build trust and we'll tackle tough questions.

You can find the blog posts that have arisen out of these several retreats in my Jewish-Muslim Dialogue posts category. In addition to those, here are two published essays and a high holiday sermon that came directly out of these retreats:

Allah is the light: prayer in Ramadan and Elul, Zeek, 2009

New depths in Jewish-Muslim Dialogue: Jewish Privilege, Zeek, 2014

Children of Sarah and Hagar: a sermon for Rosh Hashanah morning, 2014

July 29, 2016

Ain't nothing like the real thing

This is a short passage from Jewish With Feeling, co-written by Joel Segel and Reb Zalman z"l -- I reviewed the book here back in 2005. We talked about this passage a couple of weeks ago on the final day of Joel's Big Sky Judaism: The Everyday Thought of Reb Zalman class at the ALEPH Kallah.

This is a short passage from Jewish With Feeling, co-written by Joel Segel and Reb Zalman z"l -- I reviewed the book here back in 2005. We talked about this passage a couple of weeks ago on the final day of Joel's Big Sky Judaism: The Everyday Thought of Reb Zalman class at the ALEPH Kallah.

I love Reb Zalman's metaphor of apples and prayer. When I moved to rural New England, I discovered that a honeycrisp apple picked right off the tree is mind-blowingly glorious! And it bears almost no resemblance to a golden delicious apple that's spent who-knows-how-long in storage. (If you don't live in a place where great apples are grown, extrapolate to something local and seasonal where you are.)

We all know that a factory-farm-grown piece of fruit that's spent ages in a refrigerator box doesn't hold a candle to something fresh and organic and picked right off the tree in season, in context, in the place where its roots have drawn sustenance. And Reb Zalman z"l recognized that the same can be said of the difference between rote unthinking prayer, and "the real thing."

The first thing that changed my life when I encountered living Jewish Renewal at the old Elat Chayyim on my very first retreat was Jewish Renewal prayer. (I wrote about that a little bit in a blog post in 2012 -- Ten years in Jewish Renewal.) That's where I first experienced contemplative chant-based prayer, where one takes pearls from the liturgy and sings them over and over, going deeper and deeper into the words and their meaning. That's where I first experienced ecstatic prayer, where one can get so swept up in the davenen and the melodies and harmonies that one enters another state of consciousness altogether. That's where I first discovered that I could talk not only about God but also to God. It's not hyperbole to say that my life has never been the same.

Reb Zalman used to talk about "freeze-dried" prayer. Our siddurim (prayerbooks) are like the dehydrated or freeze-dried food we send into space with our astronauts, but in order to be nourished, we need to add the "hot water" of heart and soul. We need to enter into the words on the page, to be willing to open our hearts, to take the emotional risk of speaking not about the Divine but to the Divine. And the difference between "wrapped and refrigerated" prayer and deep devotional davenen is as dramatic as the difference between a pasty pale wintertime grocery store tomato and a ripe, flavorful, spectacularly delicious heirloom tomato plucked from the vine and eaten before it's even cooled off from the August sunshine in which it was sustained.

When I write about prayer, I tend to write most often about joyful prayer -- like the Kabbalat Shabbat service with Nava Tehila at the ALEPH Kallah two weeks ago. But sometimes deep davenen comes from a place of grief and fury, and that too can be sustaining to heart and spirit. What heart and spirit need is full expression. Meaningful prayer isn't just about being clappy-happy -- it's about being real, and bringing your real self, your whole self, to your davenen. It's about opening yourself up. It's about seeking the real thing, and seeking to be the real thing, instead of settling for the out-of-season peach that barely has any flavor.

Here's one more pearl from Reb Zalman:

Experiences of God are not that hard to come by: all that's required is a little yearning, a little searching, a welcoming of God within. Va-asu li mikdash v'shochanti b'tocham, says the book of Exodus (25:8): Only set aside a place, and I will come.

May it be so. Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate!

July 21, 2016

Not by Might

I'm honored to have a poem in Not By Might: Channeling the Power of Faith to End Gun Violence, edited by Rabbi Menachem Creditor with a forward by Shannon Watts of Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense.

Shannon Watts writes:

"The emergence of Rabbis Against Gun Violence and this powerful collection of American faith voices reassures me that citizens of every variety are ready to stand together, to speak, preach, and act to demand an end to the ongoing American gun violence epidemic."

The anthology features work by Sarah Tuttle-Singer, Rabbi Robyn Fryer Bodzin, Rabbi Michael Bernstein, Rabbi Matt Rosenberg, Lorraine Newman Mackler, Rabbi Michael Knopf, Rabbi Simcha Y. Weintraub, Rabbi Evan Schultz, Rabbi Hannah Dresner, Rabbi David Evan Markus, Alden Solovy, Rabbi Jesse Olitzky, Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Hermmann, Diane O'Donoghue, Rachel Weinberg, Rob Eshman, Rabbi Ben Greenberg, Rabbi Richard Myles Litvak, Rabbi Ron Fish, Rabbi Noah Farkas, Rabbi Jeffrey Salkin, Margo Hughes-Robinson, Rabbi Marcus Rubenstein, Eileen Soffer, Rabbi David Lerner, Amy Ramaker, Rabbi Salomon Gruenwald, Marc Howard Landas, Rabbi Seth Goldstein, Rabbi Daniel B. Gropper, Rabbi Rick Sherwin, Rabbi Aryeh Cohen, Francine M. Gordon, Rabbi Gary S. Creditor, Rabbi Jeremy Markiz, Rabbi Yael Ridberg, Rabbi Daniel Kirzane, Rabbi Menachem Creditor, Rabbi Annie Lewis, David Paskin, Rabbi Denise Eger, Rabbi Larry Bach, Rabbi Danielle Upbin, Barbara Schutz, Stacey Zisook Robinson, Lisa Rappoport, Liav Shapiro Gilboord, Nicole Roberts, Rabbi Sara O'Donnell Adler, Rabbi Jill Berkson Zimmerman, Maxine Lyons, Rabbi Kim Blumenthal, Rabbi Shawn Israel Zevit, Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt and Rabbi Aaron Alexander, Rabbi Ben Herman, Rabbi Philip Weintraub, Rabbi Michael Adam Latz, and Joy Gaines-Friedler. (And me, of course.)

Here's a review of the collection on the URJ website. Copies are available on Amazon. Deep thanks to Rabbi Menachem Creditor for putting this volume together.

New for The Wisdom Daily: life in the imperfect tense

The folks at The Wisdom Daily have published my latest essay. It's about my sense that divorce happens in the imperfect tense. (The decision to end the marriage may now be in the past, but it's also always continuing in to the present.) And it's about how the hard emotional work of ending a marriage maps for me, this year, to where we're at on the Jewish calendar. Here's a taste:

...This is hard work. And sometimes I am tempted to try to bypass it. Can’t I just focus on the positive, and turn my attention away from what hurts?

Not if I want to heal, I can’t. When a wound is infected, ignoring it or pretending it isn’t there won’t help. The only thing to do is grit one’s teeth and clean out the wound, and maybe suture it gently so that it can finish closing on its own. When the wound is emotional rather than physical, the same holds true.

No one likes to look at what hurts. But if we don’t face our own brokenness, we can’t sweep away the shards and prepare to rebuild.

That’s the lesson of this time of year on the Jewish calendar...

Read the whole thing: Exploring my imperfection during my divorce.

July 17, 2016

Capstone of my Kallah: Kabbalat Shabbat with Nava Tehila

The absolute highlight of my week: Kabbalat Shabbat with Nava Tehila.

Photo by Brielle Page.

My week at Kallah had a lot of highlights. Teaching was one of them -- getting to spend a week teaching some of my favorite classical midrashim (interpretive stories) and creating a safe container within which students could write and share their own midrash. Co-leading shacharit on Thursday morning was another -- Rabbi David and Rabbi Evan and I co-led a service around the firepit, beginning with the cowboy modah ani, which always feels extra-appropriate in Colorado!

But the capstone of my week, the absolutely most special part for me, was Friday night davenen. Friday night is supposed to be both soulful and celebratory as we welcome the Shabbat bride, the Shekhinah, the Queen, into our midst. I'd been looking forward to this Kabbalat Shabbat for months, hoping that it would give me some good "juice" to take home with me. And oh, holy wow: Kabbalat Shabbat at this year's ALEPH Kallah was everything I needed it to be and then some.

My son with an angel, on the pre-Shabbat walk.

The evening began with everyone in splendid whites, as is our custom here (following the custom of the kabbalists of Tzfat.) There was live music (Shabbat love songs) outside my dorm, and people in angel wings blessing us and pointing the way across campus to where we would daven. The kids got special white sparkly Shabbat facepaint. There is nothing like walking across a neighborhood (even an ad hoc one) calling "good Shabbes" to others who are beaming and celebrating too.

On Shabbat morning there were six different davenen options (I went to the kids' / family service, expertly led by Ellen Allard and the Kirtan Rabbi.) But on Friday night, we who were planning the Kallah chose to have only one service, and it featured the leaders of Nava Tehila, the Jewish Renewal community of Jerusalem. Friday night was the one time during the week when we wanted everyone to be together, for Kabbalat Shabbat and for the festive banquet-style meal that followed our prayer.

Reb Ruth, Yoel, and Dafna led davenen, as is their custom now, in the round. In the middle was an empty space (like the Holy of Holies in the Temple of old), circled by a ring of davenen leaders and musicians, circled by concentric rings of us. Because we were facing each other (rather than facing a bimah or stage), because in the middle was open space (sometimes filled with dancing daveners), I felt as though the music and the prayer were naturally arising among and between us.

The last time Nava Tehila led davenen at Kallah was 2009, and I was there, and it was amazing. This time was even more so.

The leaders of Nava Tehila:

Dafna Rosenberg, Rabbi Ruth Gan Kagan, Yoel Sykes.

With words, with customs, with kavanot (intentions), they brought the holy city of Yerushalayim into our midst and brought us into its glow. And their holy levi'im (the musicians accompanying them) included several of my nearest and dearest, which made it extra-special -- beloved faces, beloved voices, co-creating this extraordinary Shabbat for us and with us. As we davened and danced it felt like we were more than the sum of our parts. All of our voices, all of our hearts, raising sparks with joyous song.

I was surrounded by a community of some 500 ardent participants. I let it sweep me up: I danced in the aisle, I sang my heart out, I felt goosebumps in the silence after each psalm (as Reb Ruth once said, "If you've ever wondered what glory is...? It's this feeling in the room right now.") The six psalms of Kabbalat Shabbat became a pilgrimage, building awareness of transcendence, and then with "Lecha Dodi" we brought in immanence, unifying the Holy One of Blessing with the Shabbat Queen.

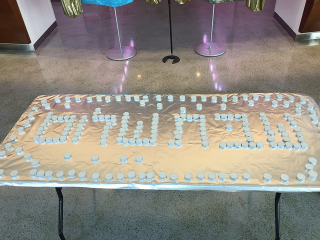

Shabbat tealights, before lighting.

I listen to Nava Tehila all the time -- especially their latest album, Libi Er / Waking Heart, the title track of which inspired the first poem in what is now Texts to the Holy. When I sing along with their music in the car, I remember every time I've been blessed to daven with them: in Jerusalem in 2008, at the Kallah in 2009, in Jerusalem in 2014... Now when I sing with their cds, or when I daven and lead davenen using their melodies, I'll remember this extraordinary night at the Kallah.

Here's Nava Tehila's Kabbalat Shabbat Playlist on YouTube. These are the melodies they used at our Kabbalat Shabbat, which they sent out in advance so that as many people as possible would know the melodies and be able to fully participate in davenning along. I expect to listen to this playlist a lot on Friday nights to come, when I am home alone and need to connect myself back to the spiritual sustenance I found in that glorious Friday night davenen at the 2016 Kallah.

July 15, 2016

Jewish Renewal and the Jewish future on Judaism Unbound

A while back Rabbi David and I were interviewed for the Judaism Unbound podcast, wearing our ALEPH Alliance for Jewish Renewal co-chair kippot. Our episode is the first episode in a four-part series that will also feature The Kitchen (and its Hello Mazel initiative), OneTable, and (as always) podcast co-hosts Dan Libenson and Lex Rofes -- and it's now live and available for download and listening!

At Or Shalom in Vancouver on the Listening Tour.

We talked about the history of Jewish Renewal and its core tenets, about "inventing" one's own form of Judaism, about the tension between structure and flexibility in Judaism writ large, and what it might look like to give the next generations the "keys to the car" and let them shape the Judaism they most need.

Here are a few teasers to whet your appetitite:

“What is the Judaism that you yearn for? What is the Judaism of the future that you want to see? And the follow-up question becomes ‘How can we help build that Judaism?’ ‘How can you help bring that about?’” -- Rachel

“There is no such thing as the Renewal prayer book. The Renewal prayer book defeats the point. You should be able to evolve a Renewal experience from any book or no book at all..."

"It’s not like you have to go to minyan three times a day or else you’re not a good Jew. What does it mean to evolve a Judaism where there are many [other] on-ramps? Well, some people are going to resonate with music. Some people are going to resonate with meditation. Or making a meal, or social justice. Whatever brings you to ‘wow,’ that’s the stuff that we work with." -- David

Judaism Unbound, a project of the Institute for the Next Jewish Future, describes itself as "a project that catalyzes and supports grassroots efforts by 'disaffected but hopeful' American Jews to re-imagine and re-design Jewish life in America for the 21st century." (Sounds right up ALEPH's alley, doesn't it?) Our conversation with Dan and Lex was terrific. I hope you enjoy: Jewish Renewal and the Jewish future on Judaism Unbound.

July 14, 2016

The smith speaks

I had work for a while.

The women donated mirrors

and I made the basin for the place

where God's presence dwells.

Since then I've tended goats.

What else is there

for a coppersmith to do

in this unsettled wilderness?

I missed the tasks of forging

but no one becomes free

without some sacrifice.

Still, others grumble.

They say Moshe dragged us here

to feed his ego. They bitch

if Moshe and God really cared

we would never have left Egypt.

In response God sent snakes.

Wailing spread across the camp

as limbs blackened and puffed up,

as puncture wounds putrefied.

The families of the bitten

begged Moshe to seek God's help.

As though they hadn't slandered him

to anyone who would listen.

As though their attributions

wouldn't wound him, wouldn't

bruise his human heart.

I don't know how he set that aside

but this morning he instructed me

to go to the men for their bracelets.

I crafted a curling snake

as copper-red as tongues of fire.

Moshe said "mount it on a miracle."

A flagpole was the best I could do.

When the snakebit looked upon it

their wounds disappeared.

How did the snake I myself made

channel healing from the One?

Remembering now, my hands shake.

I want to return to my goats.

This poem arises out of this week's Torah portion, Chukat. The people rebel against Moshe and God, and in response God sends a plague of poisonous snakes. When the people ask Moshe to intercede, God tells Moshe to make a copper snake and that those who look upon it will be healed.

This poem arises out of this week's Torah portion, Chukat. The people rebel against Moshe and God, and in response God sends a plague of poisonous snakes. When the people ask Moshe to intercede, God tells Moshe to make a copper snake and that those who look upon it will be healed.

Reading the parsha this year, I find myself wondering about the anonymous smith who made the נְחַ֣שׁ נְחֹ֔שֶׁת / the copper snake. This year I'm also feeling a lot of empathy for Moshe, who both leads and serves a community that repeatedly speaks ill of him and of their journey.

During the class I'm teaching on midrash (we're both reading and discussing classical midrash, and writing midrash of our own), this poem is what I've been working on during our writing time.

The opening stanza references a teaching from Rashi, that the Israelite women donated their copper mirrors in order for them to be hammered into the washbasin and laver for the mishkan, the place where God's presence dwelled within and among the people.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers