Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 4

May 8, 2025

The Day Will Rogers Became The Cherokee Kid

May 4, 2025

Ena of the Plains

April 18, 2025

Texas Jack Just In

April 5, 2025

Baptiste Bayhylle: The Chief They All Look To

April 2, 2025

Val Kilmer

March 26, 2025

More AI Imagery

March 2, 2025

Tin Jesus on Horseback

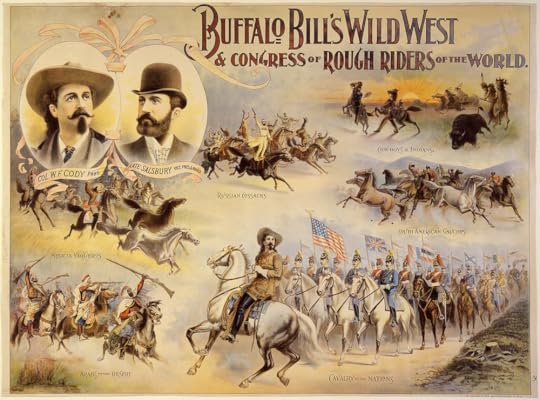

Tin Jesus on Horseback: Buffalo Bill’s Bitter Business and Personal Feuds

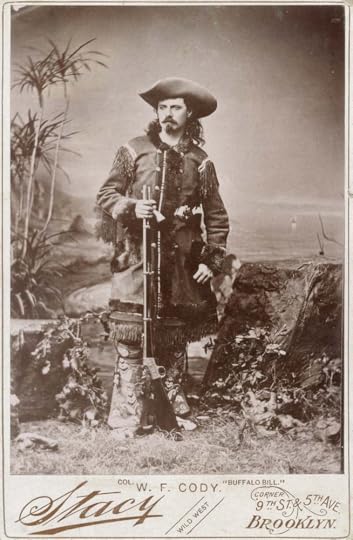

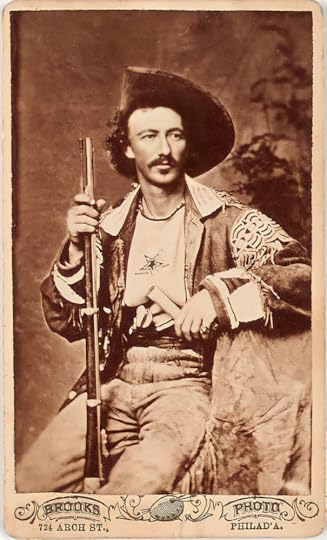

Buffalo Bill Cody was a legend, but legends are not built alone. His rise to fame depended on key business partnerships, yet those partnerships were often fraught with conflict. Cody’s inability to manage money, his loyalty to problematic associates, and his drinking habits created tensions that led to dramatic fallouts with some of his closest allies. Nowhere was this more evident than in his feuds with two of his most notable partners—Nate Salsbury and Dr. William “Doc” Carver.

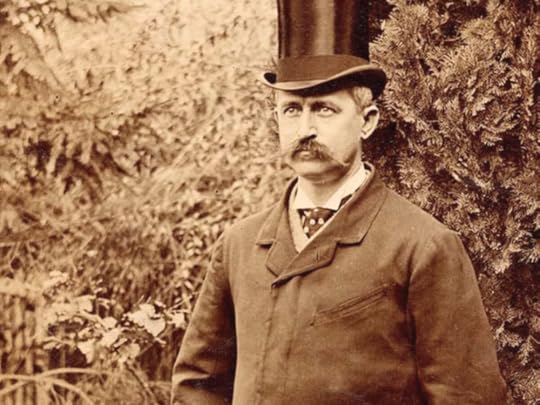

Nate Salsbury was the driving business force behind Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, handling logistics, finances, and promotion. Without Salsbury, the show might not have achieved its enormous success, but the partnership was strained. Salsbury grew frustrated with Cody’s reckless spending and poor financial decisions, particularly when Buffalo Bill invested heavily in the irrigation project that founded the town of Cody, Wyoming. Their relationship was further tested by Cody’s drinking and his tendency to surround himself with friends who drained money from the operation. Before his death in 1902, Salsbury documented his grievances in a memoir he never published, referring to his years working with Buffalo Bill as “Sixteen Years in Hell.” He derisively described Cody as a “Tin Jesus on Horseback,” a man with a grand vision but little control over his affairs.

Salsbury’s unpublished manuscript was filled with venom. “Buffalo Bill makes a virtue of keeping sober most of the time during the summer season, and when he does so for an entire season, he looks on himself as a paragon of virtue,” he wrote. “But when the fever gets into his brain, he forgets honor, reputation, friend, and obligation in his mad eagerness to fill his hide with rotgut of any kind.” He went on to accuse Cody of breaking promises, saying, “He becomes so utterly lost to all sense of decency and shame that he will break his plighted word and sully his most solemn obligation.” Even in death, Salsbury’s words remained a testament to the bitter dissolution of their once-lucrative partnership.

As Salsbury’s health failed, he became increasingly paranoid that Buffalo Bill would find a way to cut his family out of the profits of the Wild West show. “All the brutal things that Cody is capable of are well known to me,” he wrote. “I want this record to stand so that when he starts in to malign me, as he will do, my friends will have my answer.” The mistrust between them had become irreparable, yet Salsbury remained with the Wild West show until his dying day, unwilling—or perhaps unable—to sever ties completely. His family, however, did not share his attachment. When he passed in 1902, his heirs moved quickly to protect what was left of his legacy, selling off his interests in the show and ensuring that Buffalo Bill would no longer have control over Salsbury’s share of the profits.

Another significant rift occurred between Cody and Doc Carver, a sharpshooter and showman who initially partnered with him to launch the Wild West spectacle. Carver’s ego matched Cody’s, and their differing visions for the show led to an early split. While Carver saw himself as an equal partner, Cody ultimately sought a larger spotlight. Carver, embittered, went on to create his own show, claiming that he was the true mastermind behind the Wild West performance. The rivalry between the two became personal, with Carver challenging Cody’s version of events and attempting to outdo him in the show circuit. Carver’s bitterness persisted long after their partnership dissolved, and he spent years trying to compete with the Wild West’s enduring popularity.

Despite these conflicts, Buffalo Bill’s charisma kept his name at the forefront of entertainment. However, his poor business sense and fractured relationships left him vulnerable. After Salsbury’s death, Cody’s financial troubles worsened, forcing him into questionable business deals that led to the eventual loss of control over his own show. He had once been the undisputed star of a global phenomenon, but by the twilight of his career, he was a performer in another man’s circus, haunted by the ghosts of his past feuds and failures.

February 28, 2025

A Broken Marriage

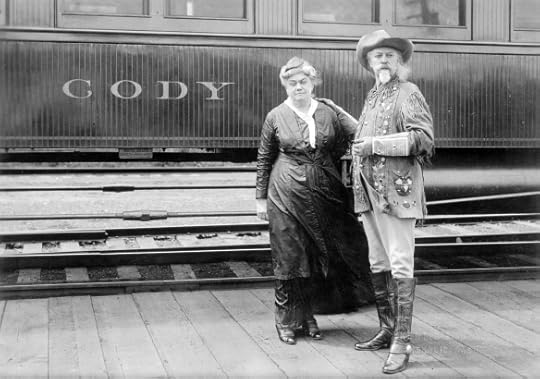

The Turbulent Relationship Between Buffalo Bill and Louisa Cody

Buffalo Bill Cody and Louisa Cody’s marriage was one marked by triumphs and tragedies, passion and pain. Their union endured the chaos of Buffalo Bill’s ever-growing fame, the demands of his career, and the personal losses that shaped their lives. Though their love story began with promise, it was ultimately tested by years of separation, financial struggles, and public scandal. At its lowest point, their marriage seemed irreparably shattered, but the tragedies they suffered together would ultimately bring them back to each other.

Buffalo Bill’s success as a scout, hunter, and showman brought both wealth and instability to the Cody household. Louisa, a woman who longed for stability, found herself married to a man constantly on the move. His Wild West show toured extensively, taking him across the country and overseas, leaving Louisa to manage the household alone. His frequent absences led to rumors of infidelity, which Louisa could neither confirm nor escape. Resentment grew between them, reaching a breaking point when Cody, in 1904, filed for divorce—citing cruelty and even accusing Louisa of attempting to poison him.

The accusations shocked those who knew them, and the resulting legal battle played out in the press, damaging Buffalo Bill’s carefully cultivated public image. Louisa fought back fiercely, denying the poisoning allegations and painting her husband as an unfaithful, reckless man who had neglected his family. The court ultimately ruled against Cody, refusing to grant the divorce. Though legally bound, the couple remained estranged, their relationship appearing beyond repair.

Yet, despite their animosity, the losses they endured as parents would prove stronger than their grievances. The deaths of their children, particularly their beloved daughter Arta, devastated them both. Arta’s passing in 1904, amid their divorce proceedings, forced them to confront their shared grief. The sorrow that once drove them apart now became the common ground that softened their hearts toward one another. In the wake of such overwhelming loss, they found solace not in separation, but in unity.

By 1910, Buffalo Bill and Louisa had reconciled. After years of hostility, they came back together in their final years, sharing quiet moments at their home in Cody, Wyoming. Though their marriage had been scarred by accusations and estrangement, in the end, love and loss had bound them together once more. Their story, like the great frontier Buffalo Bill so often romanticized, was one of hardship, endurance, and ultimately, reconciliation.

February 26, 2025

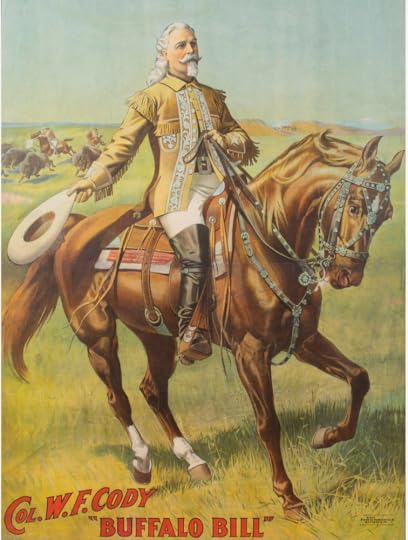

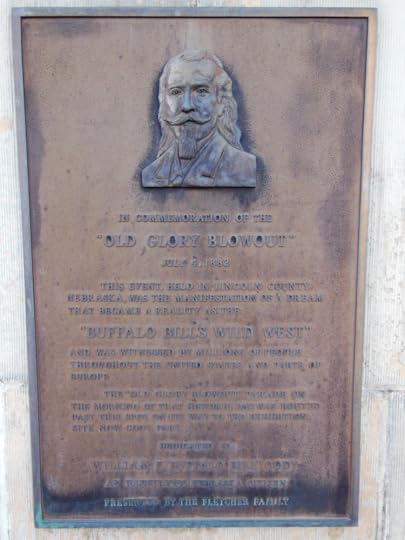

The First Rodeo: Buffalo Bill’s Old Glory Blowout and the Birth of a Tradition

On July 4, 1882, in North Platte, Nebraska, Buffalo Bill Cody did what he did best—put on a show. What was supposed to be a simple Fourth of July celebration turned into something bigger: an exhibition of frontier skills that would set the template for rodeos to come. He called it the Old Glory Blowout, and in true Cody fashion, it was more than just a party. Cowboys competed, crowds cheered, and a new American tradition took its first steps into the spotlight.

To understand how Buffalo Bill came to recognize the cowboy as a natural performer, you have to look at his partnership with Texas Jack Omohundro. Before Texas Jack, Cody saw cowboys as tough, resourceful, and necessary. After Texas Jack, he saw them as legends.

Jack had been a real-deal cowboy, trailing cattle, riding hard, and roping anything that moved. He lassoed a buffalo for the Niagara Falls Museum, proving that cowboy skills weren’t just for the range. More importantly, he took those same skills onto the stage when he and Buffalo Bill toured together in Scouts of the Prairie. It was Texas Jack who first showed audiences that cowboy life could be more than hard work—it could be entertainment.

The Old Glory Blowout was an experiment in spectacle. There were horse races, shooting contests, and cowboy competitions that looked an awful lot like modern rodeo events. Roper

s showed their skill, riders proved they could stay on the meanest broncos, and the people of North Platte saw, many for the first time, the athleticism and artistry of the working cowboy.

Buffalo Bill was already thinking bigger. He’d spent a decade in theaters, learning how to shape a narrative and captivate an audience. That instinct carried over into the Blowout, where he turned the everyday work of cowboys into something thrilling. He framed it as a patriotic display, a way of celebrating the frontier spirit, and he made sure the press took notice.

The North Platte Telegraph later described the Old Glory Blowout as “the most consequential Fourth of July since the first.” Cody’s celebration didn’t just entertain—it laid the foundation for two major cultural institutions: rodeo and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. According to historian Adam Jones, Cody “offered something to the people that they never saw before.”

Cody’s larger-than-life presence guaranteed the event’s success. A local reporter from the Omaha Daily Bee arrived by train and noted that the town was “alive to the importance of the occasion.” The day began with a booming cannon and a parade featuring the North Platte Cornet Band, Civil War veterans, Sunday-school children, and carriages filled with spectators. The highlight of the event was Cody’s reenactment of a buffalo hunt, where cowboys lassoed and rode wild bison—a spectacle that foreshadowed what would later become Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

Texas Jack passed away in 1880, but his influence on Buffalo Bill never faded. When Cody launched his Wild West show, cowboys weren’t just background players—they were stars. The show’s programs honored the cowboy as a symbol of the American West, a clear nod to the way Texas Jack had embodied that role. Every time Buffalo Bill’s riders lassoed a steer or busted a bronc, they were paying homage to Jack’s legacy.

Buffalo Bill never set out to invent rodeo, but the Old Glory Blowout lit a spark. Within a decade, cowboy contests were popping up all over the West, and rodeo was on its way to becoming the defining sport of the frontier.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West spread the cowboy legend across two continents, but it all started in North Platte, on a hot summer day in 1882, when a showman with a knack for spectacle turned a holiday celebration into history.

February 22, 2025

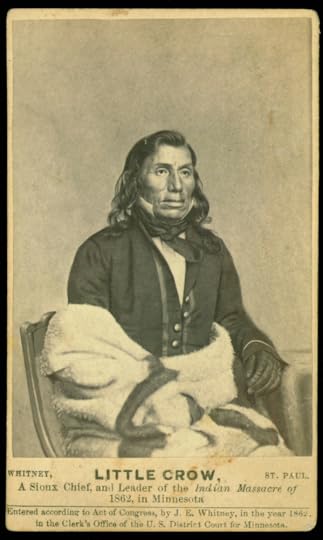

Little Crow

Little Crow, leader of the Mdewakanton Dakota during the 1862 Dakota War, knew his people had little chance of victory. He had tried to avoid war, warning that the U.S. government would never let the Dakota reclaim their land. But when years of corruption, starvation, and broken treaties boiled over—set off by a deadly dispute over stolen eggs—he was left with no choice. If the Dakota were to die, they would die fighting. When he realized he couldn't disuade the Dakota warriors from carrying the fight to the white settlers, he told them, "Little Crow is not a coward: I will die with you." Under his reluctant leadership, the Dakota launched a series of attacks on settlements and military outposts. They struck fear into the frontier, but their weapons and numbers were no match for the full force of the U.S. Army. By late September, after a crushing defeat at Wood Lake, the war was lost.

Little Crow fled west with his son, seeking refuge among the Lakota and later in Canada, but no one would take him in. He wandered for months, a leader without a nation, before making the fateful decision to return to Minnesota in the summer of 1863. On July 3, while picking raspberries near Hutchinson, he and his son were spotted by a farmer, Nathan Lamson, and his teenage son. The Lamsons opened fire. Little Crow was hit and killed instantly, while his son managed to escape. Not knowing the identity of the Dakota man they had just shot, the Lamsons stripped the body, scalped it, and dragged it back to town. In a grotesque display of vengeance, settlers stuffed firecrackers into the dead man’s ears and nose and tossed the remains into a slaughterhouse pit. Later, the body was decapitated.

For 41 days, the corpse lay unidentified. It wasn’t until Little Crow’s son, Wowinape, was captured that the truth emerged. He told the U.S. Army that his father had been killed near Hutchinson. Soldiers returned to the slaughterhouse, dug up the remains, and identified the body by an old wrist injury. The state of Minnesota paid Nathan Lamson a $500 bounty for killing the Dakota leader. In the years that followed, Little Crow’s body was reduced to a collection of macabre trophies. The Minnesota Historical Society acquired his scalp in 1868, his skull in 1896, and other bones at unknown times. For decades, these human remains were put on public display.

It wasn’t until 1971—108 years after his death—that Little Crow was finally laid to rest. His remains were returned to his grandson, Jesse Wakeman, for burial. By then, the war he had fought and the cause he had died for were long over, overshadowed by other, later, conflicts with the Lakota and Apache and the life-toll consequences of Manifest Destiny. Little Crow had tried to stop the war before it began, had begrudgingly led his people when he realized that the actions of rash young men had left him with no other choice, and had paid for it with his life—only to be dismembered, desecrated, and displayed like a trophy.