Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 9

May 8, 2024

Part 4 - Porter Rockwell: Legends of the Old West

Part 4 of 6 in a series on Orrin Porter Rockwell I wrote for Legends of the Old West. In episode 4, "New Zion," we explore the complex and often controversial figure of Orrin Porter Rockwell during the Mormon migration to Utah. This episode situates Rockwell within the broader context of the burgeoning conflicts that would eventually escalate into the Utah War. Listeners are given a glimpse into Rockwell's role as Brigham Young's scout and protector, highlighting his strategic importance and the moral complexities that accompany his actions on the frontier.

Throughout the episode, the narrative threads together Rockwell’s involvement in key events, such as tense negotiations with Native American tribes and the logistical challenges of leading an advance party through unknown territories. These stories are framed within the looming shadow of growing tensions between the Mormon settlers and the U.S. government. Rockwell's contributions are depicted not just in terms of what his Mormon compatriots saw as his personal bravery but also through the lens of the impending conflict, setting the stage for the Utah War.

For anyone drawn to the intertwining of personal narratives with major historical events, this episode offers a compelling preview of the conflicts that will reach their zenith in the next chapter of the series. By the end, listeners will appreciate the depth of the historical landscape and the pivotal role played by figures like Rockwell, who navigated through a period marked by both creation and crisis in the American West. This episode not only provides insights into Rockwell’s life but also foreshadows the intense military and political struggles that will be detailed in the next episode.

Also available on Spotify:

And Apple Podcasts:

All of Legends of the Old West's podcasts are available at:

https://blackbarrelmedia.com/legends-of-the-old-west/

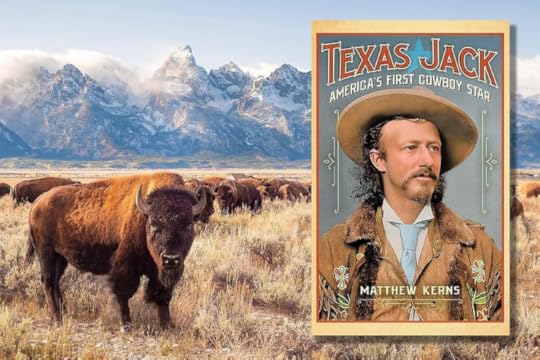

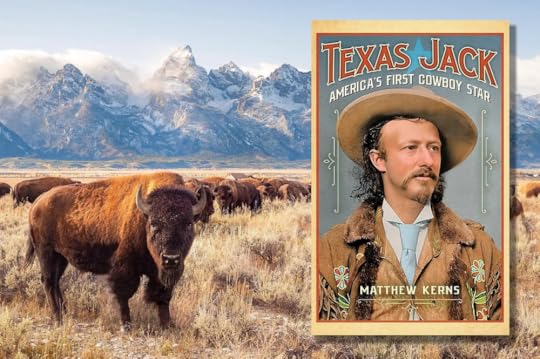

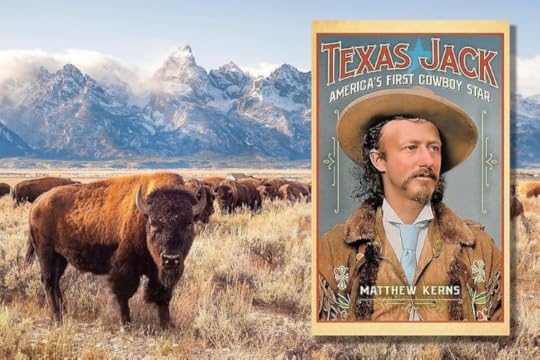

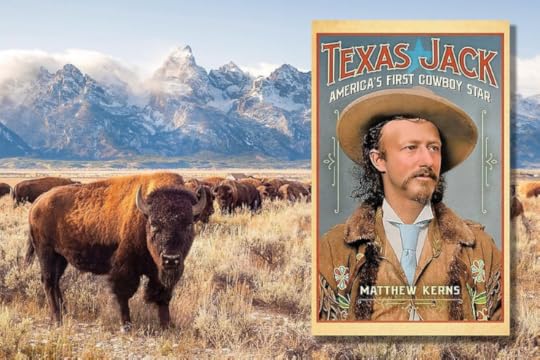

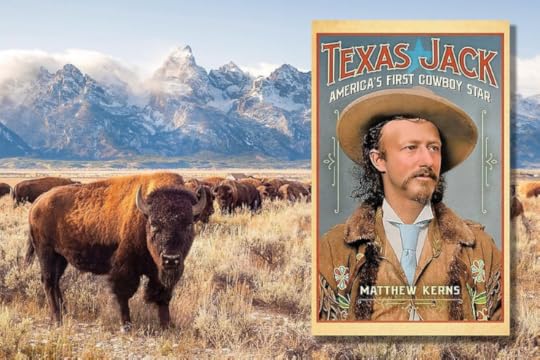

Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star by Matthew Kerns is available at:

May 1, 2024

Part 3 - Porter Rockwell: Legends of the Old West

Part 3 of 6 in a series on Orrin Porter Rockwell I wrote for Legends of the Old West.In "A Mormon Sampson," episode three of six in a series for Legends of the Old West, the narrative centers on Orrin Porter Rockwell, renowned for his unwavering loyalty and strength. After Rockwell's arrest for the attempted murder of former Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs, he experiences a tumultuous transport back to Independence, Missouri, marked by a drunken stagecoach driver and a series of misadventures, including an overturned coach and a night spent self-navigating the vehicle in heavy shackles. Despite these challenges, Rockwell demonstrates resilience and quick-thinking, attributes that deepen his mythos among the Mormon community.

This episode also explores his time in a Missouri jail, where, despite a crowded and oppressive environment, he attempts a daring escape with his new cellmate using tools hidden in saddlebags.

The latter part of the episode details Rockwell’s trial and the community’s response to his prolonged imprisonment without conviction, which ironically ends with a minimal sentence after a technically guilty verdict. The episode reflects on Rockwell's legendary status, likened to a "Mormon Sampson," underscoring his role as both a symbol of and a literal fighter against oppression. This portrayal builds a complex image of Rockwell, capturing his physical and moral battles, his strategic mind, and his unshakeable loyalty to Joseph Smith and the Mormon leaders. The narrative sets the stage for further exploration of his contributions and the enduring legacy he creates within the Old West folklore.

Also available on Spotify:

And Apple Podcasts:

All of Legends of the Old West's podcasts are available at:

https://blackbarrelmedia.com/legends-of-the-old-west/

Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star by Matthew Kerns is available at:

April 24, 2024

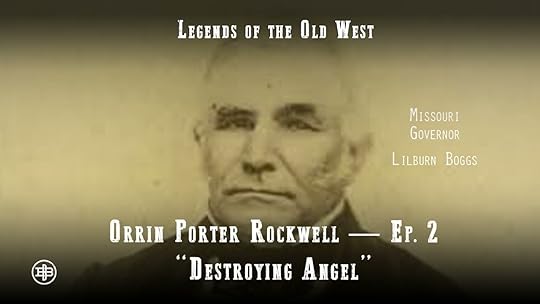

Part 2 - Porter Rockwell: Legends of the Old West

Part 2 of 6 in a series on Orrin Porter Rockwell I wrote for Legends of the Old West.

In episode 2, "Destroying Angel," we delve into the tumultuous period during the rise of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and the controversial figure Orrin Porter Rockwell. Several years after their forced departure from Jackson County, Missouri, Rockwell, along with other members of the Latter-Day Saints, formed a covert society aimed at executing the will of Joseph Smith and defending the church against internal and external threats. They are known as the "Sons of Dan." Porter Rockwell, fiercely loyal to Smith, believes he is divinely mandated to ensure the destruction of Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs following a prophecy. This belief sets him on a path that cements his infamous legacy.

Tensions escalate between the Missouri settlers and the growing Mormon community, largely due to religious and political differences. The Mormons' opposition to slavery poses a threat to the local slaveholding populace, leading to violent confrontations. The tension eventually erupts in chaotic skirmishes, the issuance of an "Extermination Order" by Governor Boggs, and the subsequent dire consequences for the Mormons. Amidst mounting violence, Rockwell's actions, driven by deep-seated belief and allegiance, illustrate the complex interplay of faith, loyalty, and extremism during a pivotal era in American religious history.

Also available on Spotify:

And Apple Podcasts:

All of Legends of the Old West's podcasts are available at:

https://blackbarrelmedia.com/legends-of-the-old-west/

Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star by Matthew Kerns is available at:

April 17, 2024

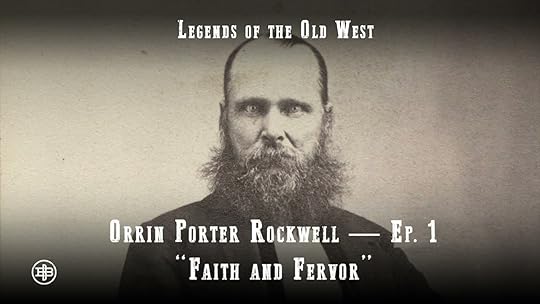

Part 1 - Porter Rockwell: Legends of the Old West

Part 1 of 6 in a series on Orrin Porter Rockwell I wrote for Legends of the Old West.

In "Faith & Fervor", the premiere episode of a six-part series, we delve into the tumultuous and faith-driven life of Orrin Porter Rockwell. Born amidst the fervor of the Second Great Awakening in early 19th century America, Rockwell’s journey from a devout Mormon family in Massachusetts to the Western frontier is explored. We trace his deep connections to the origins of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, detailing his close association with Joseph Smith and the early Mormon pioneers. The episode sets the stage for Rockwell's controversial legacy as a feared enforcer and protector of his faith, juxtaposed against the sweeping religious and cultural transformations of the time. From his early life in the "Burned Over District" of New York to the violent clashes and migration to Missouri, Rockwell’s story begins with both a literal and metaphorical journey from faith to fervor.

Also available on Spotify:

And Apple Podcasts:

All of Legends of the Old West's podcasts are available at:

https://blackbarrelmedia.com/legends-of-the-old-west/

Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star by Matthew Kerns is available at:

April 15, 2024

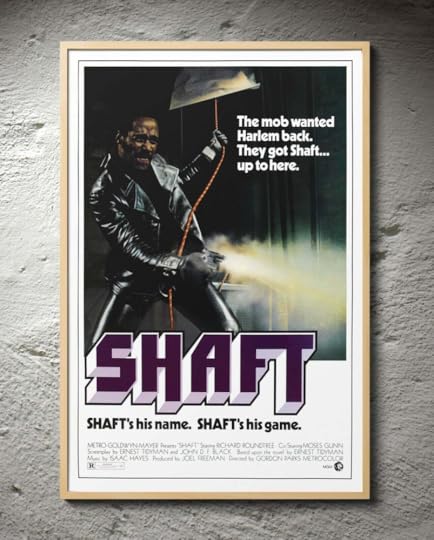

Shaft

It might seem counterintuitive that the shared icon of masculine aspiration for a group of Southern, white, middle-class, suburban kids growing up in the late 80s and early 90s in Chattanooga, Tennessee, was “the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks,” Shaft.

You’re damn right.

And yet my friends and I must have watched the VHS copy that we initially rented, and soon purchased, dozens of times. From the moment Richard Roundtree walks up the subway steps in his brown leather trenchcoat to the funky hi-hat and wah-wah guitar that leads off Isaac Hayes's theme for the movie, we were intrigued. A moment later, when he flips off a cab driver while yelling “Up yours” as he crosses a street, confident in the knowledge that whatever it is that is driving him to wherever he is going precludes the flow of traffic, we were hooked.

I remember exactly how it happened. It started, as did many of the things I discovered in adolescence and retained in adulthood, with my dad. One hot summer day, he mentioned that while he was stationed at Cam Ranh Airforce Base during the Vietnam War, there were only two air-conditioned buildings offering respite from the heat and humidity. The first, he said, was the library. The second was the theater, where he remembered watching Shaft during his deployment. That name, Shaft, resonated, as did the rhetorical question my father asked us that day:

“Who’s the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks?”

A trip to the local video rental place—no, not the Blockbuster, which was further from home, past the mall and next to the TCBY place—revealed that our go-to rental for that period, The Last Waltz, was unavailable. A decision needed to be made, and I suggested Shaft.

“Shaft?” someone asked.

You’re damn right.

I can't now recall our assumptions about what the movie's plot would be. I certainly don't remember thinking that this film would leave a profound mark on our personal aesthetics and sensibilities. The foundations were laid during the course of that first viewing. During the brief period when I was in college but had not yet moved out of my parent’s house, the two posters that adorned the walls of my bedroom were a picture of Dexter Gordon at the Royal Roost and the original theatrical one-sheet for Shaft. "Shaft's his name," it said. "Shaft's his game."

It didn’t occur to me until much later that the world I lived in was, in many ways, a world shaped by the movie I had just 'discovered.' The character of John Shaft, as portrayed by Richard Roundtree, broke new ground when the film was released in 1971, with its portrayal of a Black leading man who was not just central to the narrative but commanded it with a blend of charisma, confidence, and self-assurance rarely afforded to Black characters in mainstream media up until then. Historically, Black actors were often relegated to roles that were subservient or comical—sidekicks or stereotypes that reinforced the racial hierarchies of the time. Shaft, however, was the antithesis of these constraints. He was a protagonist who was not only formidable and fearless but also possessed a magnetic appeal and moral complexity that challenged viewers to rethink the archetype of the American hero.

This representation had been revolutionary during an era when the civil rights movement had only recently achieved significant legislative victories, and America was grappling with deep-seated racial divisions. In portraying Shaft as a stylish, savvy, and sexually powerful detective who navigated the urban landscape with authority and autonomy, the film not only offered a new kind of cinematic hero but also projected a vision of Black empowerment that resonated beyond the silver screen. This shift heralded a wave of 'blaxploitation' films that, despite their critiques, expanded roles for Black actors and brought to the forefront narratives centered on the experiences and struggles of Black Americans.

It was a movie that was more than mere entertainment. Shaft challenged the status quo and initiated a dialogue about race, representation, and resistance that has left an indelible mark on the landscape of cinema, continuing to influence filmmakers and audiences alike. Without Richard Roundtree as Shaft, there is no Chadwick Boseman as the Black Panther. The core of their appeal is similar—they embody empowerment, dignity, and resilience in the face of adversity. Shaft was not only the pioneer but remains a seminal figure in cinematic history, setting a standard for character depth and cultural significance that is challenging for any role or character to surpass. The character remains so strong that it has engendered two sequels starring one of my favorite actors, Chattanooga's favorite son, Samuel L. Jackson.

That’s what it did for cinema and for popular culture. Here’s what it did for us: we saw Roundtree's Shaft as the epitome of cool. Because John Shaft is disillusioned with the man, with the culture, with the system, and with the police detectives he works closely with, he resonated with our terminally disaffected generation. But beyond that, he resonated because he was a man of substance that we all aspired to. He was strong, but he was also smart. He was fierce, but he was also funny. And he carried himself with an assured confidence that seemed always natural. This wasn't swagger or machismo; this was not just what a man looked like; this was what THE man looked like.

For a group of suburban, middle-class white kids growing up in the deep South, Shaft’s defiance and self-sufficiency struck a particular chord. Our daily lives were worlds away from the gritty streets of Harlem depicted in the film, but the notion of carving out one's identity on one's own terms had universal appeal. Shaft's independence and his unapologetic way of navigating a world that often seemed rigged against him provided a form of escapism and inspiration. It was not just his style or his cool demeanor that captivated us, but his ability to command respect in a society fraught with tensions and divisions. We didn’t face the challenges that John Shaft did, but whatever challenges we did face, we wanted to face them like we imagined Shaft would.

This character, who stood up against corruption and injustice, who was both a lover and a fighter, presented a new kind of role model. Unlike the cowboys and the traditional heroes in earlier movies, who often embodied a type of rugged individualism still aligned with mainstream values, Shaft was a true rebel with a cause. It wasn't just his actions that challenged the system, but his very existence. How he faced these challenges in this system, sprinkled with wit and a sharp sense of justice, taught us about resilience and integrity in the face of adversity.

Moreover, Shaft's influence extended into how we viewed the fabric of our own communities. While we could never fully grasp the racial dynamics Shaft navigated, his interactions with both allies and antagonists showcased the complexities of trust, loyalty, and personal alliances. These dynamics transcended the immediate conflicts he faced, highlighting a broader, more intimate struggle with relationships and personal integrity in a divided world. These were lessons that transcended the boundaries of race and class, urging us to look beyond our insulated suburban experiences to the wider world around us, with all its conflicts and possibilities.

In essence, Shaft helped shape our perceptions of what it meant to be cool, to be just, and to be fiercely independent. He was more than just a character on screen; he was a symbol of the kind of men we aspired to become—men of principle, courage, and unwavering self-assurance.

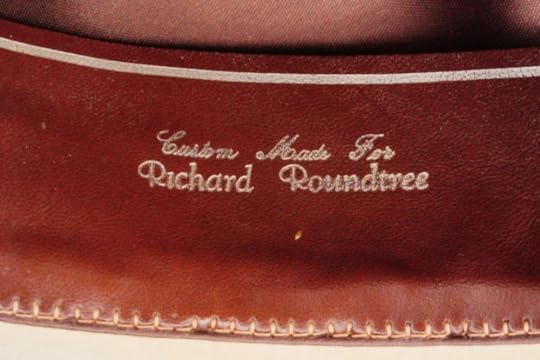

In October of 2023, Richard Roundtree died from pancreatic cancer. He was an actor, a trailblazer, and an icon. His family organized an estate auction this April, and among the items auctioned were several of Roundtree’s hats, including some worn on screen throughout his storied career.

Last year, when I received the Western Heritage Award for Best Magazine Article from the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum for a piece on Texas Jack Omohundro, I found myself reflecting on my own authenticity. "I always question if I can pull off a cowboy hat," I admitted openly, "I'm no cowboy, and I worry about being seen as a poser, an outsider, a pretender." My roots aren’t Western, but Southern, and despite my frequent travels through the American West—from the rugged terrains of Montana to New Mexico—I've always felt like an outsider to the cowboy culture I admire and write about.

When last year’s Western Heritage Awards ceremony ended, I tucked my Stetson back into its box, contemplating the nature of authenticity. "Maybe when you win a Western Heritage Award, you can wear whatever hat you want," I mused, thinking back on the old adage that the clothes don't make the man. Shaft was cool in his leather coat, but not because of his leather coat.

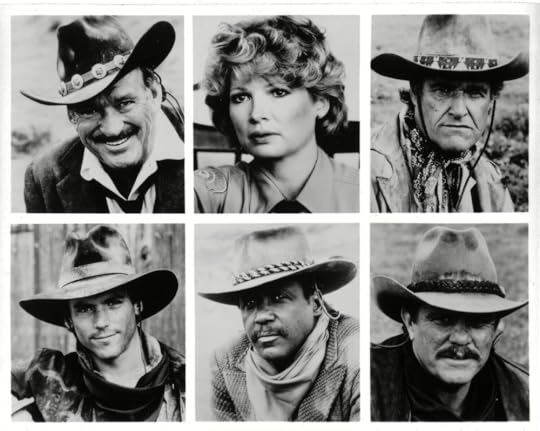

That reflection on identity and authenticity took a fascinating turn this year when I won an auction for a cowboy hat owned and worn by Richard Roundtree during the filming of the 1986 television show Outlaws. In the show, Roundtree played Isaiah "Ice" McAdams, an escaped slave turned clever outlaw and now a private detective, much like a Wild West John Shaft.

This hat, crafted by Rand’s Custom Hats in Billings, Montana, and kept in Roundtree’s personal collection until his passing, carries with it a little bit of his legacy of defiance and cool. I wore it to this year’s Western Heritage Awards.

Does wearing Richard Roundtree’s cowboy hat impart any of his legendary mojo on me? Logically, the answer is no. A hat is just a piece of apparel, and this one is just an amalgamation of beaver fur felt, leather sweatband, and horsehair hatband. It’s just an object. But do I feel just a little bit cooler, stand just a little taller, walk with just a little more swagger, and feel just a little more confident knowing that this isn’t just a cowboy hat, but the cowboy hat that belonged to Richard Roundtree—to Shaft?

You’re damn right.

April 5, 2024

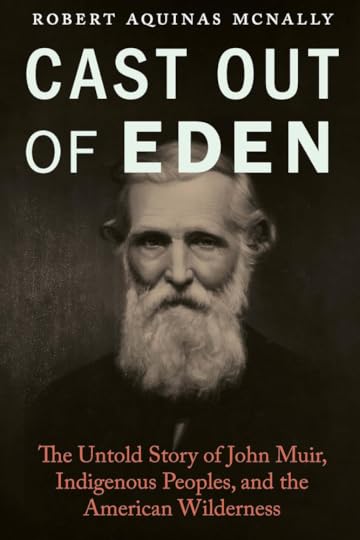

A Review of Cast Out of Eden

Yesterday, I received my copy of Robert Aquinas McNally's new book, Cast Out of Eden: The Untold Story of John Muir, Indigenous Peoples, and the American Wilderness. I was lucky enough to get to read this one before it was released so that I could provide a review blurb, and I was absolutely blown away. I had been impressed by McNally's previous book The Modoc War (you can read my review here), but I wasn't quite prepared for just how much of an impression this book was about to make on me.I finished reading it last summer as my wife and I returned from the Western Writers of America conference in Rapid City, South Dakota. Having this book in my head while I drove through the Badlands, the Black Hills, and especially when we crossed Pine Ridge Reservation, it made me consider my own thoughts about National Parks, preserved lands, and Native people. Reconciling my joy that these places remain wild must be balanced with my terror at what was done to the people who inhabited them. And to reckon with the tension that creates internal to myself, it was very helpful to have McNally's narrative voice walking me through Muir's journey and failings vis a vis Native peoples.

So, perhaps needless to say, I LOVED the book.

This was the short review blurb that I gave to Bison Books:

“A thought-provoking masterpiece. Following the life and achievements of John Muir, ‘Father of the National Parks,’ McNally masterfully shows how one of America’s greatest achievements—the preservation of our wildest places—is indelibly tied to one of our most abject failures—the treatment of the Native Americans who lived there.”—Matthew Kerns, Spur and Western Heritage Award–winning author of Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star

Here is a full review:

"Cast Out of Eden" is a monumental work by Robert Aquinas McNally that is as breathtaking in its scope as it is in its depth of insight. McNally's profound exploration of John Muir's life, particularly his complex relationship with America's wilderness and the Indigenous peoples, presents a narrative that is as enlightening as it is heartrending.

Unlike previous biographies of Muir that often veered into hagiography, "Cast Out of Eden" offers a nuanced and critical perspective. While acknowledging Muir's pivotal contributions to the conservation of America's natural landscapes, McNally courageously delves into the more problematic facets of his legacy. The book addresses the overlooked consequences of Muir's environmental crusades, particularly the disregard for the rights and humanity of Native American communities whose displacement was rationalized by the very initiatives Muir championed. This approach provides a more balanced understanding of Muir's impact on America's wilderness preservation efforts, contrasted with the experiences of the Native American men, women, and children who had lived in the vast unspoiled wilderness Muir so revered.

"Cast Out of Eden" is a thought-provoking masterpiece that manages to capture the essence of one of America's greatest achievements — the preservation of its wild lands — while also laying bare the moral costs of this endeavor. McNally masterfully shows how the sanctification of wilderness areas is indelibly tied to the dispossession and suffering of the Indigenous peoples who lived in harmony with these lands for millennia.

Reading this book before attending the Western Writers of America conference in Rapid City, South Dakota, particularly enhanced my appreciation for McNally's narrative mastery. Driving through the Badlands, the Black Hills, and crossing the Pine Ridge Reservation, I found myself deeply contemplating the complex layers of beauty and tragedy that comprise our national heritage. McNally's lyrical narrative voice was a guiding light through this introspective journey, helping me to grapple with the uncomfortable truths about the lands we cherish and the histories we must reckon with.

"Cast Out of Eden" offers an unflinching look at Muir's vision of wilderness that excluded the very people who had cultivated these landscapes for centuries. McNally does not merely present a critique but invites us to imagine a future where America's wild spaces are inclusive, where the legacy of conservation is one of healing and justice for all its peoples.

In closing, Robert Aquinas McNally's "Cast Out of Eden" is more than just a biography; it is a clarion call to acknowledge the juxtaposed triumphs and tragedies of our past, to understand the present, and to strive for a more equitable future. It is a must-read for anyone who cares deeply about the natural world and the complex, often painful history that has shaped our relationship with it and the people who inhabited it.

Cast Out of Eden: The Untold Story of John Muir, Indigenous Peoples, and the American Wilderness by Robert Aquinas McNally is available at Amazon:https://amzn.to/49t4HsKAnd wherever books are sold.

April 1, 2024

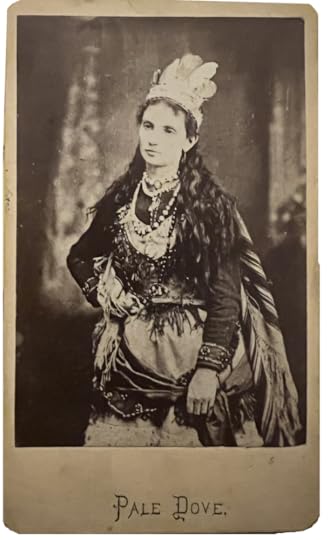

New Photo of Giuseppina Morlacchi

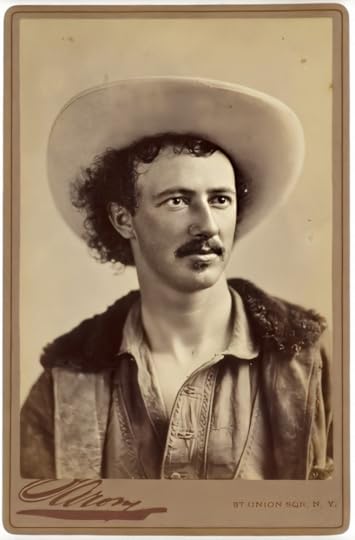

This is a photo of Giuseppina Morlacchi, wife of Texas Jack and prima ballerina star of the original western, The Scouts of the Prairie. This particular image has never been digitized and was recently purchased at the Baltimore Antique Arms Show by collector Dr. Tony Sapienza. Tony has generously shared the image with me and given me permission to share it with all of you.

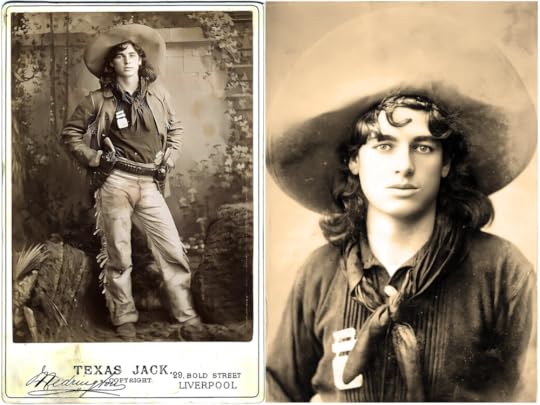

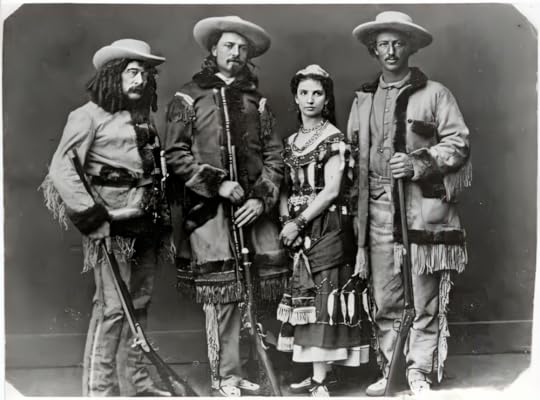

When The Scouts of the Prairie opened in Chicago in December of 1872, Morlacchi was the only trained actor in the main cast. Her costars, the play's author Ned Buntline, the famous hunter turned scout Buffalo Bill Cody, and the famous cowboy turned scout Texas Jack Omohundro, had no dramatic training and no idea what they were doing. They famously forgot every line on opening night, only to discover that the audiences were more interested in seeing real heroes than fine actors.

Giuseppina, who was often billed as "The Peerless" Morlacchi, was a trained prima ballerina, and had conquered the theaters and opera houses of Europe before coming to America to star in an early stage musical called "The Devil's Auction." She created an immediate sensation in New York City, where she was serenaded by the New York Philharmonic, and her legs were insured for $100,000, leading one commentator to proclaim that her legs were worth "more than Kentucky!"

There are several pictures from that first season showing Giuseppina in costume as Dove Eye, described by critics as “the beautiful Indian maiden with an Italian accent and weakness for scouts." The following season, Morlacchi married her costar, Texas Jack, and agreed to rejoin his show, still with Buffalo Bill Cody but now having replaced Ned Buntline with the famous lawman and gunslinger Wild Bill Hickok. The plot of the play was similar, but names were changed, and the character of Dove Eye was replaced with Pale Dove. It is unknown if this image is from the first or second season. The costume matches images from the first season, but the name at the bottom indicates the character she played in the second.

[image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error]In closing, we extend our heartfelt thanks to Tony Sapienza for his invaluable contribution to preserving the rich tapestry of the American West. Through his generous sharing of the never-before-seen photograph of Giuseppina Morlacchi, we gain not just a glimpse into the life of Texas Jack Omohundro's illustrious wife but also a deeper insight into the legacy she carved in the annals of American popular culture. Giuseppina Morlacchi, "The Peerless" Morlacchi, not only dazzled audiences across America and Europe with her balletic prowess but also played a pivotal role in shaping the narrative of Western shows, bringing sophistication and artistry to the stage shows about the rugged frontier. Her journey from the grand opera houses of Europe to the heart of the American West, alongside legends like Texas Jack, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Wild Bill Hickok, showcases the blending of cultures and the birth of a uniquely American form of entertainment that continues to captivate our imaginations. This article, illuminated by Dr. Sapienza's generosity, serves as a tribute to her indelible impact on the cultural landscape of the West.

For readers intrigued by the dynamic life and times of Texas Jack and the colorful figures who shared his world, further exploration can be found in "Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star," available on Amazon. This book delves deeper into the legacy of these iconic personalities whose lives painted the canvas of the American frontier with bold strokes of adventure, heroism, romance, and unparalleled showmanship.

March 25, 2024

Disney, Texas Jack, & Antiques Roadshow

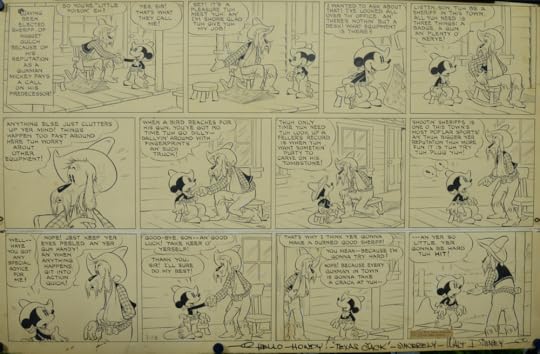

In a recent episode of PBS's "Antiques Roadshow," a piece of Americana sparked the imaginations and nostalgia of viewers as an original Mickey Mouse comic strip was unveiled. The artwork, with its fine lines and charismatic rendering of the beloved cartoon character as a Wild West cowboy, was revealed to be the handiwork of Walt Disney himself. Notably, the piece bore a whimsical sign-off from Disney: "Hello - Howdy - Texas Jack - Sincerely - Walt Disney," a salute to the enduring symbol of the cowboy and the spirit of the Wild West. This 1937 treasure, a snapshot of animation history and Western lore combined, was appraised at an impressive value of between $15,000 and $20,000, a testament to the lasting appeal of Disney's creations and the iconic figure of Texas Jack Omohundro.

Walt Disney's choice to sign off with "Hello - Howdy - Texas Jack" alongside his name on an original piece of Mickey Mouse comic strip artwork is a telling nod to the enduring legacy of the cowboy and the American West. In 1937, some 57 years after Texas Jack Omohundro's death, his name still carried the essence of the cowboy ethos and the untamed spirit of the Wild West. The iconic Mickey Mouse depicted as a cowboy reflects Disney's understanding that the cowboy, embodied by figures like Texas Jack, was an archetype ingrained in American culture.

Omohundro was more than just a cowboy; he was a performer, a scout, and one of the earliest cowboy stars of the American stage alongside his contemporaries, "Buffalo Bill" Cody and "Wild Bill" Hickok. His life was a tapestry of adventure, from guiding cattle drives across treacherous territories to performing in Wild West shows that captivated audiences with the myths and legends of frontier life.

The fact that Disney, a master storyteller and animator, would evoke Texas Jack in a comic strip attests to the cowboy star's influence. It was a symbol understood by audiences then as it is now—a shorthand for the adventure, independence, and rugged individualism that the West represented. This choice by Disney underscores the lasting impact of Texas Jack on American pop culture, symbolizing the spirit of a bygone era that still captured the public's imagination in the 20th century, and continues to do so today.

March 18, 2024

Rescued by Texas Jack?

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before…

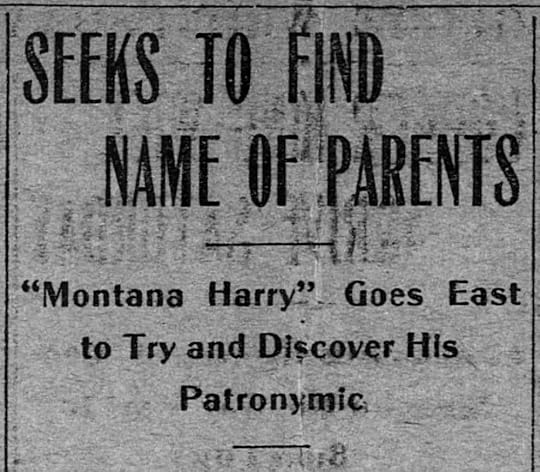

A westward-bound wagon train meets a grim fate at the hands of an Indian band. Chaos ensues, wagons are laid to waste, lives are tragically lost, and amidst the turmoil, a young boy and two girls find themselves captives, their lives forever changed. Enter the daring Texas Jack, a cowboy and scout of legend, who emerges to rescue the boy from his plight and shepherd him back to the realms of the known world. This boy, adrift in identity yet undeterred in spirit, vows to carve out a legacy of his own. And the boy at the heart of our story answers to the name...Montana Harry?

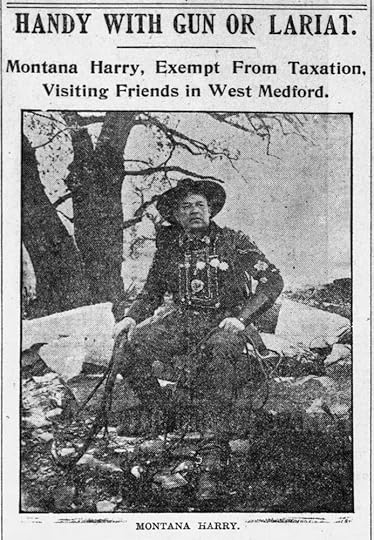

In August of 1904, articles like this one popped up in newspapers across the country. This one is from the Saint Paul, Minnesota, Globe newspaper:

The story of Montana Harry is a tale that, on its face, bears a striking resemblance to the story of Texas Jack Junior. Both narratives feature young boys captured by Native Americans, subsequently rescued by Texas Jack Omohundro, and raised to adulthood with Jack’s aid. Both men used their harrowing childhood stories to carve out careers in the burgeoning world of Wild West entertainment, following in the dusty footsteps of Wild West legends like Buffalo Bill Cody. But when we dig a little deeper, Montana Harry's story begins to unravel at the seams, especially when compared to the (slightly) more verifiable narrative of Texas Jack Junior.

The first red flag in Montana Harry's tale is the timeline. He claims to have been rescued by Texas Jack and raised on his ranch, yet the historical record places Texas Jack Omohundro in North Platte, Nebraska, by 1870, not roaming the wilds of Montana. There, Jack worked as a bartender at Lew Baker's saloon, interspersed with scouting missions alongside his good friend Buffalo Bill Cody. This settled lifestyle in North Platte directly contradicts Harry's account of a ranch upbringing under Texas Jack's guidance.

Moreover, Harry's assertion that he joined the Army in 1871 casts further doubt on his story. By that time, Texas Jack had been in North Platte for two years and had already embarked on his career as a scout. He would soon transition into show business, activities well-documented and leaving little room for the ranching life in Montana Harry describes. The historical record simply does not support the possibility of Texas Jack being in Montana to rescue Harry, much less raising him on a ranch that didn't exist.

The narrative inconsistencies extend beyond just dates and locations. While Texas Jack Junior's story fits within the known timeline of Texas Jack Omohundro's life, Montana Harry's account relies heavily on sensationalized newspaper articles and lacks independent verification. The vivid details of his rescue, the presentation of his scalp by an Indian chief, and his subsequent career as a cowboy, scout, and ranch owner echo the tropes of dime novels more than the documented realities of the Wild West.

Montana Harry's story, while compelling, seems to have been crafted to capitalize on the fame of Texas Jack Omohundro and the insatiable appetite of the American public for Wild West tales. The narrative served not only to elevate Harry's status as a performer in the same vein as Buffalo Bill but also to imbue him with an aura of authenticity and adventure that was crucial for success in the world of Wild West shows.

Montana Harry's account of his early years among the Sioux and his subsequent rescue by the legendary Texas Jack is rendered even more suspect by other outlandish claims that pepper his narrative. In a 1902 interview with the Boston Globe, Harry purported to be the "sole survivor of the scouts attached to General Custer’s command at the massacre of the Little Big Horn," a feat that history books and eyewitness accounts fail to corroborate. Adding layers to his already questionable tale, Harry also claimed to be the lone white graduate of the Carlisle Indian School, a historically significant institution known for its role in the assimilation policies toward Native American children, but with no records to support Harry's attendance, much less his unique graduate status. Moreover, Harry's assertion that his purported status as a "white Indian" rendered him exempt from taxation stretches the bounds of credibility even further. These fantastical additions to his life story, far from lending him the air of mystery or heroism he perhaps sought, instead cast a shadow of doubt over the entire narrative, making it difficult to sift the truth from his tall tales.

It's within the realm of possibility that Texas Jack Junior, much like Montana Harry, wove a narrative fabric around his origins that leaned more towards fiction than fact. But if Junior did indeed craft a tale about his past, he spun a yarn that was not only more believable but also far more captivating and comprehensive than Montana Harry's attempt. Junior didn't just adopt the name casually; he embedded it deeply into his identity, to the extent that "Texas Jack" appeared on crucial legal documents, ranging from immigration forms to his daughter Hazel Jack's birth certificate. The name "Texas Jack" is printed on his death certificate, anchoring his legend in official records. Moreover, he passed this legacy onto his only son, whom he named Texas Jack, a child who tragically passed away at the tender age of nineteen months in Chicago in July of 1892. This level of commitment to the persona suggests a depth of connection to the identity of Texas Jack that goes beyond mere storytelling or showmanship, embedding Junior's tale firmly within the fabric of his real-life experiences and the historical record, despite the potential for embellishment.

In the end, while both stories captivate with tales of adventure, survival, and identity, a closer examination reveals that Montana Harry's story is less a recounting of actual events and more a masterclass in the art of Wild West myth-making. In the landscape of American folklore, where truth and fiction blend seamlessly, Montana Harry's tale stands as a testament to the lasting legacy of Texas Jack Omohundro and the enduring power of storytelling, even when those stories stretch the bounds of believability.

If this glimpse into the tangled tales of the Wild West has captured your imagination, dive deeper into the life of the man who embodied the cowboy spirit like no other. Explore "Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star" for a compelling journey through the true story of an American icon. Your adventure awaits at Amazon: https://amzn.to/4aiHWsE.

March 8, 2024

Celebrating Morlacchi on International Women's Day

On this International Women's Day, we journey back to the vivid and tumultuous landscape of the American Wild West to spotlight a figure who shimmered with unparalleled grace on the rugged frontier stage, Giuseppina Antonia Morlacchi. Known affectionately as "the Peerless Morlacchi," her life story is a captivating tale of talent, passion, and pioneering spirit in an era dominated by the lore of cowboys and Indians.

Born in Milan, Italy, Giuseppina Morlacchi was a dance prodigy who honed her craft at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Dancing and Pantomime at La Scala. Her performances across Europe captured the hearts and imaginations of many, earning her the moniker "The Peerless" for her unmatched grace and skill. However, it was her bold decision to cross the Atlantic that marked a pivotal chapter in her story, leading her to the glittering stages of New York and eventually to a defining role in American entertainment history.

Morlacchi's arrival in the United States was met with great anticipation and fanfare, with the Academy of Music orchestra playing on the street beneath her hotel window and her famous legs insured for $100,000, the equivalent of nearly $2.2 million today. Her debut in New York was a sensation, with performances that drew acclaim for her expressive artistry and technical mastery. Beyond the footlights, she became a fearless advocate for her fellow dancers, women without her fame and power, defending their rights and dignity against managerial injustices with unwavering resolve.

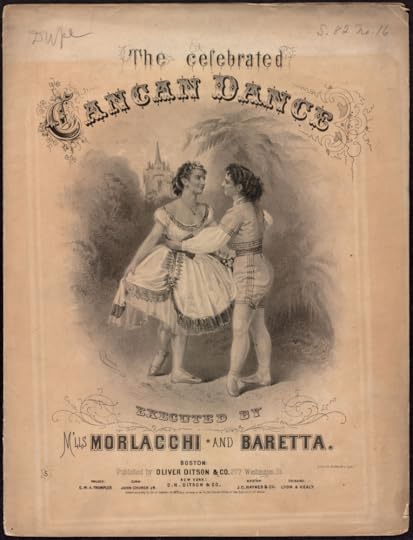

Adding to the rich tapestry of Morlacchi's contribution to the American entertainment landscape was her introduction of the scandalous cancan to Boston. After her New York debut, where she had been showered with so many roses that she struggled to navigate the stage, Morlacchi aimed to surpass the acclaim with something even more provocative. On December 23, 1867, at the Theatre Comique in Boston, she presented a dance America had never witnessed before: the cancan. This audacious performance featured a series of high kicks and lifted skirts, offering audiences a glimpse of her black stockings and colored undergarments, a move that was as scandalous to 19th-century America as the rock 'n' roll gyrations of Elvis Presley and the mop-top haircuts of The Beatles would be a century later.

It was within this whirlwind of acclaim and adulation that Morlacchi's path converged with that of Texas Jack Omohundro, a genuine cowboy and scout who, alongside Buffalo Bill Cody, was just venturing into the novel world of theater. In "The Scouts of the Prairie," a dramatic play crafted by none other than the famous dime novelist and scoundrel Ned Buntline, Morlacchi starred as Dove Eye, the "beautiful Indian maiden with an Italian accent and a weakness for scouts." This role not only provided her status as the First Lady of the Wild West but also showcased her as a pioneering force in the evolution of American entertainment, blending theatrical artistry with the raw, untamed essence of the frontier.

The impact of "The Scouts of the Prairie" on the theatrical world was immediate, setting the stage for the genre that would evolve into Buffalo Bill's Wild West show and later into the westerns that dominated American television and film. Despite critical reviews that varied in their appreciation for Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill, the authenticity and real-life heroism of its stars and the acclaimed grace and talent of Morlacchi captivated audiences. The play toured extensively, from New York City's Broadway to small towns, bringing the allure of the Wild West to a broad audience and establishing a new genre of entertainment that celebrated American history and mythology.

Giuseppina Morlacchi and Texas Jack's passionate romance added a profound depth to their professional collaboration, intertwining their legacies in the annals of Wild West history. Their relationship, marked by mutual respect and admiration, demonstrated the powerful influence of love and partnership in shaping both personal and professional lives.

Morlacchi's journey from the ballet stages of Milan to the theaters of the American frontier embodies the spirit of International Women's Day—celebrating the achievements of women who have pushed the boundaries of their fields and paved the way for future generations. Her legacy as the First Lady of the Wild West and her pioneering contributions to American entertainment continue to inspire and captivate those who delve into the rich tapestry of the Wild West era.

For those interested in exploring the life and contributions of Giuseppina Morlacchi further, more details can be found in my book "Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star," which delves deeper into her pivotal role in shaping the Wild West's cultural legacy.https://amzn.to/3Tcl5rP